Abstract

We investigate antitumor efficacy and 2D and 3D intratumoral distribution of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38) from polymeric depots inside U-87MG xenograft tumor model in nude mice. Results showed that polymeric depots could be used to administer and controlled release of a large amount of SN-38 directly to the brain tumor model. SN-38 released from depots suppressed tumor growth, where the extent of suppression greatly depended on doses and the number of depot injections. Tumor suppression of SN-38 from depots was three-fold higher in animals which received double injections of depots at high dose (9.7 mg of SN-38) compared to single injection (2.2 mg). H&E staining of tumor sections showed that the area of tumor cell death/survival of the former group was two-fold higher than those of the latter group. Fluorescence imaging based on self-fluorescent property of SN-38 was used to evaluate the intratumoral distribution of this drug compared to histological results. The linear correlation between fluorescence intensity and the amount of SN-38 allowed quantitative determination of SN-38 in tumor tissues. Results clearly showed direct correlation between the amount of SN-38 in tumor sections and cancer cell death. Moreover, 3D reconstruction representing the distribution of SN-38 in tumors was obtained. Results from this study suggest the rationale for intratumoral drug administration and release of drugs inside tumor, which is necessary to design drug delivery systems with efficient antitumor activity.

Keywords: Biodegradable polymer, intratumoral, drug delivery system, brain tumor model, SN-38

Introduction

Brain cancer has been listed as the most lethal type of cancer because of limited treatment and its aggressive behavior. Currently, the treatments of brain cancer include radiotherapy, surgical resection, and chemotherapy.1 However, these procedures cause complications, for example, myelosuppression and immune disruption, resulting in poor performance in cancer treatment. Drug delivery systems (DDSs) are known as types of therapeutic methods that can deliver therapeutic agents to targeted cancer cells and enhance the therapeutic efficacy while limiting the side effects. An introduction of DDS has become a milestone in the clinical treatment.2 Various types of DDSs have been developed for brain cancer therapy including, liposomes3 and nanoparticles4,5 but little success have been accomplished for brain cancer chemotherapy. This is due to a lot of obstacles such as drug elimination, side effect, and physiological barriers. Blood–brain barrier, a physiological barrier with tight junctions of endothelial cells which limits the transport of drugs passing through this barrier.6 Another approach of DDSs for brain cancer chemotherapy is to directly deliver anticancer drugs in the brain, i.e. intracranial delivery, in the form of micro/nanofibers,7 wafer,8 and disk.9,10 One of the well-known products was developed by Langer R and his colleagues, Gliadel®, which is a polymer wafer that encapsulates BCNU, an anticancer drug, inside for post-surgery treatment.

7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38; C22H20O5; molecular weight [MW] = 392.31 g/mol) is an active metabolite of irinotecan (CPT-11) and a derivative of camptothecin. SN-38 acts as a topoisomerase I inhibitor and it is 1000-fold more potent than CPT-11. Its half-life is longer than those of topotecan and CPT-11. SN-38 is poorly soluble in aqueous solution (11–38 µg/mL in H2O) which limits its in vivo applications.11,12 Additionally, SN-38 is unstable in physiological pH with a very short half-life,13 where an active form (lactone) of SN-38 is converted to an inactive form (carboxylate) within 9.5 min.14 Numerous research efforts have tried to develop DDS for SN-38 including nanoparticles15,16 and dendrimer.17 SN-38-loaded polymeric depots have been extensively developed by our group from tri-block copolymers of D,L-lactide (LA), ɛ-caprolactone, and PEG or PLECs. Depots were formed by dissolving PLEC copolymers and SN-38 in glycofurol, a biocompatible solvent. Then, it was found that depots could be solidified and formed as solid implants in both phosphate buffer saline and rat brains. In vitro study showed that release of SN-38 from depots could be controlled by different parameters including copolymer composition, drug loading content, and depot size. PLEC (22.5% LA and 50 kDa) depots with 29.7% of SN-38 loading were found to release the highest amount of SN-38. Depots were also found to enhance the stability of SN-38 where SN-38 was in an active form even after 60 days of the release study. This suggests that these depots can enhance stability of SN-38 and protect it from converting to an inactive form. Cytotoxicity was confirmed using human glioblastoma (GBM) cell line (U-87MG).18,19 Biocompatibility study upon intracranial injection in rat brain was carried out by stereotactic surgery.20,21 It was found that polymeric depots can be injected at 10 µL in rat brains with no systemic or neurologic toxicity. Promising in vitro and in vivo results suggested the potential of using these polymeric depots for intratumoral administration into brain tumors.

Herein, we reported antitumor efficacy and intratumoral distribution of SN-38 released from polymeric depots inside U-87MG xenograft tumor model in nude mice. Depots were injected into tumors at different doses and number of injections. Intratumoral distribution of SN-38 was evaluated using fluorescence imaging technique based on self-fluorescent property of SN-38. Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction was used to simulate the SN-38 distribution from the depots. These results can be used to predict the intratumoral distribution and the design for the future clinical treatments.

Materials and methods

Materials

Poly(ɛ-caprolactone)-random-poly(D,L-lactide)-block-poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(ɛ-caprolactone)-random-poly(D,L-lactide) or PLEC was prepared as previously reported.22 SN-38 was purchased from Abatra Technology Company Ltd (Xi’an, Shaanxi, China). Glycofurol was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri). Tetrahydrofuran (THF) was acquired from RCI Lab-scan Ltd (Milwaukee, Wisconsin).

Preparation of polymeric depots

Polymeric depots were fabricated as previously reported.18,22,23 Briefly, 10.5 mg of SN-38 and 35 mg of PLEC (22.5% LA, MW ∼ 50 kDa) were dissolved and vigorously mixed with 100 µL of glycofurol by vortex; then this solution was drawn into 26 G syringe. It should be noted that glycofurol and SN-38 ratio were fixed at 35% w/w compared to PLEC weight.

Animals and tumor model

Human GBM cell line (U-87MG) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in EMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 110 mg/mL of sodium pyruvate. Cancer cells (5 × 106 cells) in 50 µL of phosphate buffer saline were subcutaneously implanted into the right flank of each mouse. Mice used in this study were female athymic mice (BALB/cMlac-nu) aged 6–8 weeks, and purchased from National Laboratory Animal Center, Mahidol University. Tumor volume was measured using a calliper and the ellipsoid volumes were calculated by the following formula (1/2 × height × width2).24,25 It should be noted that mice with tumor volume over 2000 mm2 were euthanized. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Health (IACUC), Thailand.

Polymeric depots administration

After three weeks of tumor preparation, mice with the tumor volume of 250–350 mm3 were randomly classified into five groups (n = 5). Mice were anesthetized by isofuran inhalation and then injected with different depot administration as described next: (1) control group: the PLEC solution (50 µL) without SN-38 was injected at the center of tumor, (2) single injection: tumors were injected by one injection (60 µL) of SN-38 + PLEC solution with the equivalent of 2.2 ± 0.2 mg of SN-38 at the center of tumor, (3) double injection at low dose: two injections (2 × 30 µL) of SN-38 + PLEC solution with the equivalent of 2.5 ± 0.2 mg of SN-38 in total was injected at two focal points of ellipse, (4) double injection at medium dose: two injections (2 × 30 µL) of SN-38 + PLEC solution with the equivalent of 4.4 ± 0.2 mg of SN-38 in total at two focal points of ellipse, and (5) double injection at high dose: four injections of SN-38 containing solution (4 × 30 µL) with the equivalent of 9.7 ± 0.3 mg of SN-38 at two focal points and two quarters points of conjugate diameters of ellipse. Tumor sizes were measured by calliper. Mice were observed for 14 days after the depot(s) injection then tumors were harvested. It should be noted that mice containing tumors with the volume over 2000 mm3 were removed.

Study of SN-38 distribution in tumors

At the end of the experiment, mice were sacrificed. Tumors were removed for drug distribution and histology studies. First, a tumor was mounted on a cryostat chuck with O.C.T embedding medium (Thermo scientific Inc., Shandon, MI, USA). Then, it was cut perpendicularly along the reference cross-section which is defined by half of the length of the widest cross-section of each tumor. Second, depots were removed from the site(s) during the process to evaluate distribution of SN-38 in the tissues. Slices for drug distribution study were cut at the thickness of 60 µm for fluorescence study (unstained) and 5 µm for H&E staining. Histology slices were analyzed by pathologist.

Quantitative analysis of SN-38 in tumor tissue

Untreated tumors were sliced by a cryostat microtome (Cryotome FSE) at the thickness of 60 µm. Series of SN-38 were dissolved in THF/H2O (80:20) solution. To construct the calibration curve, SN-38-containing tumor tissues were prepared by spreading 40 µL of SN-38/THF/H2O solution on the surface of tumor on each slice. Tissue slices were dried to evaporate THF/H2O in a black box until returning to their original weight. Fluorescent imager (KODAK In-Vivo Imaging System FX Pro, Japan) was used to determine the amount of SN-38 in the tissues using the following conditions: λexcitation = 390 nm, λemisssion = 535 nm, exposure time of 60 s, resolution at 2048 × 2048 pixel, and field of view of 2.5 × 2.5 cm. Fluorescence images were saved in BIP format and calculated the average fluorescence intensity by Carestream® Molecular imaging software (Kodak Inc., Japan). Net fluorescence intensity (NFI) was calculated by subtracting the fluorescence intensity of the THF + H2O treated tumor slice without SN-38 from the SN-38 treated tumor slice.

Fluorescence analysis

Slices were fixed to confine 3D image translation where z direction corresponds to an axial direction. Unstained slices were scanned by fluorescence imager and converted to the amount of SN-38 using a calibration curve as previously described. Images were exported to TIFF format (1024 × 1024 pixel, 16-bits) and were performed a registration process and 3D reconstruction by Fiji software.26 Fluorescent intensity of study groups was obtained by subtracting the background intensities from SN-38-free slices. Then, the amount of SN-38 in each slice was calculated. The amount and the distance of SN-38 in tumor tissues were fitted and calculated using MATLAB software (Math works, Natick, MA, USA). Area under curve of the amount of SN-38 was calculated by applying trapezoidal rule to the last measurable data point.27

Results and discussions

Antitumor efficiency

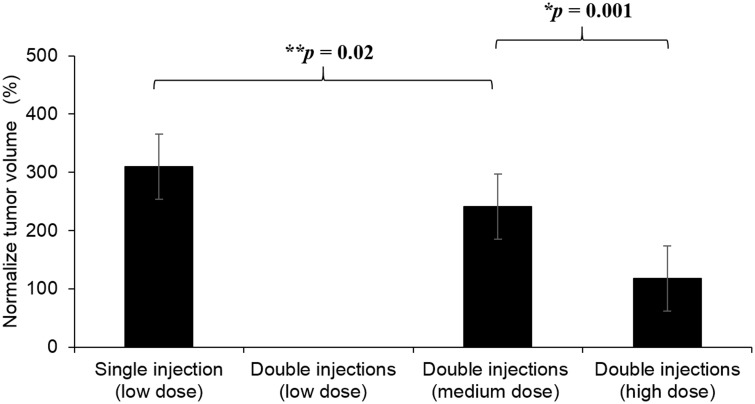

Antitumor efficiency of SN-38-loaded polymeric depots was carried out by injecting different doses and the number of injections in brain tumor model. The average tumor volume indicated that double injection at high dose demonstrated significant antitumor efficiency with 2-fold and 3-fold smaller tumor volume compared to double injections at medium dose and single injection at low dose, respectively. The comparison between tumor volume and the amount of SN-38 in tissues showed that double injections at low dose failed to inhibit growth of tumor even though the amount of SN-38 was comparable to the single injection at the same dose. Therefore, the size of all tumors in this group exceeded 2000 mm3 (295% normalized tumor volume). This may be due to inadequate local concentration of SN-38 after being divided into two injections.

SN-38 distribution in tumors

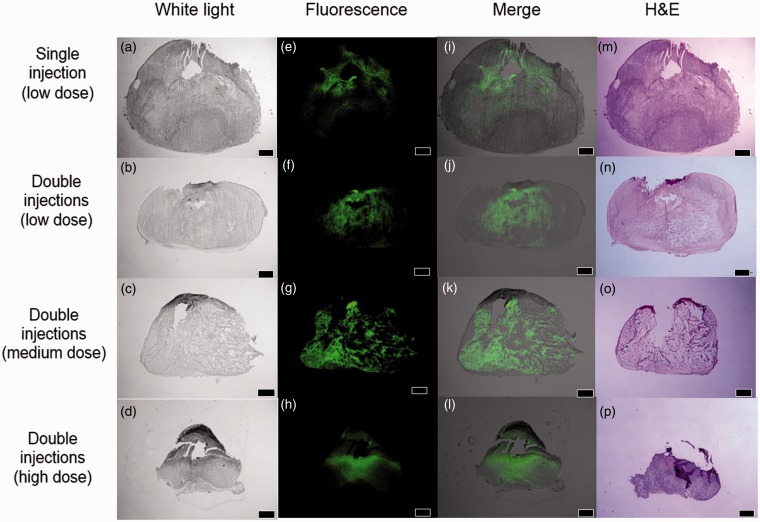

In depth analysis of SN-38 distribution inside tumors was carried out to find the explanation of different antitumor efficacy as a result of the number of injections and dose. In this study, unstained tumor slices were scanned by the fluorescent imager. Tissues were also sectioned next to the unstained slice and stained by H&E to obtain pathological information. H&E sections and fluorescent images (Figure 2) from the same tissue area after seven days of the polymeric depot injection(s) allowed clear visualization of SN-38 distributed in the tumor tissues. All groups showed fluorescence signal around the injection site(s). SN-38 inside tumors injected by single injection and double injections at low dose concentrated only at areas around injection sites and did not cover the majority of tumors (Figure 2). As a result, necrotic and viable cells were observed outside the fluorescent area. Instead, the double injections at medium and high dose provided promising results where fluorescent signal was found to cover most of tumor sections.

Figure 1.

Percentage of normalized tumor volume after different depot injection(s) for seven days. The tumor volume at the end of the experiment was normalized against the tumor volume after depot injection(s) at day 0

Figure 2.

H&E sections and fluorescent images of tumor sections seven days after injection of depots; Unstained images (white light) (a–d), fluorescent images (green) (e–h), and overlay images (i–l). H&E sections (m–p). All scale bars are 2 mm. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

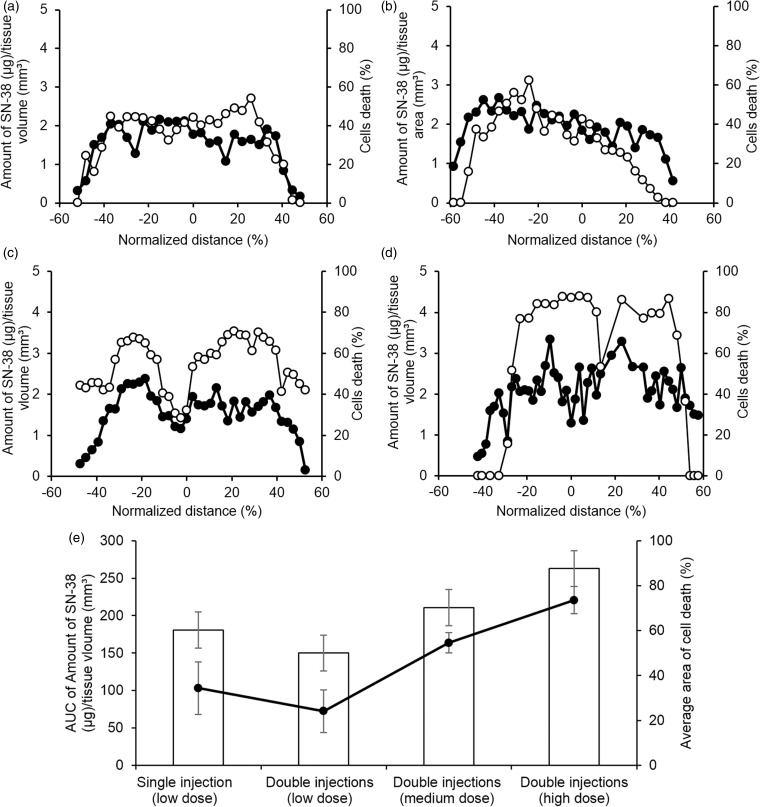

Next, NFI after correction for tissue autofluorescence in each unstained slice was plotted with the amount of SN-38 in tissues obtained from the following calibration equation NFI = 349.76 × 106[SN-38]; R2 > 0.98. The linear correlation between fluorescence intensity and the amount of SN-38 allowed quantitative determination of SN-38 in tumor tissues. The limit of detection (LOD) and noise were analyzed and evaluated. Results showed that LOD and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) of fluorescence imaging were at 0.004 and 0.0137 µg/mm3, respectively. Therefore, distribution profiles of SN-38 inside tumors were constructed as shown in the primary y-axis of Figure 3 (black circle). Cell death profile in H&E sections were also plotted by measuring the difference between the areas of live versus dead and necrotic cells in each slice as shown in the secondary y-axis of Figure 3 (white circle). For all groups, SN-38 was detected at the concentration above LOD and LOQ across tumors. This confirms the advantage of local administration and controlled release of DDSs. The percentage of cell death in all groups was above 50% when the amount of SN-38 was higher than 2.4 µg/mm3. Tumors injected by double injections at high dose clearly had higher percentage of cell death (73.6 ± 6.0%) and AUC of SN-38 in tumors tissues (262.8 ± 11.8) compared to other groups. This group could also produce more than 70% of cell death over 75% of tumor volume, where the double injections at medium dose could not reach approximately 70% of cell death in all sections. Moreover, double injections at high dose was the only one depot administration that SN-38 concentration in tissues was above 3.0 µg/mm3 and the value was statistically different from the other groups. For example, p-value of double injections at high dose versus medium dose was below 0.01. This suggested that SN-38 released from depots with double injection at high dose could cover the majority of tumor volume at the adequate concentration to produce significant cell death area inside tumors resulting in the reduction of tumor size. Compared to our previous studies, approximately 0.2 mg of SN-38 was released in vitro from PLEC depots in seven days. This is in agreement with results from this study where the amount of SN-38 in tumor tissues could be calculated in the range of 0.10–0.27 mg after in vivo release.18 Results mentioned above led to the significant tumor suppression effect of double injections at high dose. Interestingly, it could be observed that double injections with medium and high dose showed a bimodal distribution of both SN-38 and cell death in tumors, where high level of cell death was observed at the location containing high concentration of SN-38. It should be noted that double injections at low dose failed to inhibit tumor growth which was presumably due to the inadequate local concentration of SN-38, where each injection of double injections at low dose has half of SN-38 compared to single injection. This also lowered the concentration gradient of SN-38 between depots and surrounding tumor tissues. Therefore, the local concentration of SN-38 was too low to reach cytotoxic dose.

Figure 3.

Amount of SN-38 (µg/mm3) in different cross-sections of tumors injected by depots (a) single injection, (b) double injections (low dose), (c) double injections (medium dose), (d) double injections (high dose), and (e) summary of the area under curve of the amount of SN-38 in tissues (µg/mm3) presented by bar graph compared to the average of normalized area of cell death presented by line graph. Amount of SN-38 (µg)/tissue volume (mm3) and percentage of cell death are represented by “•” and “○”, respectively. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

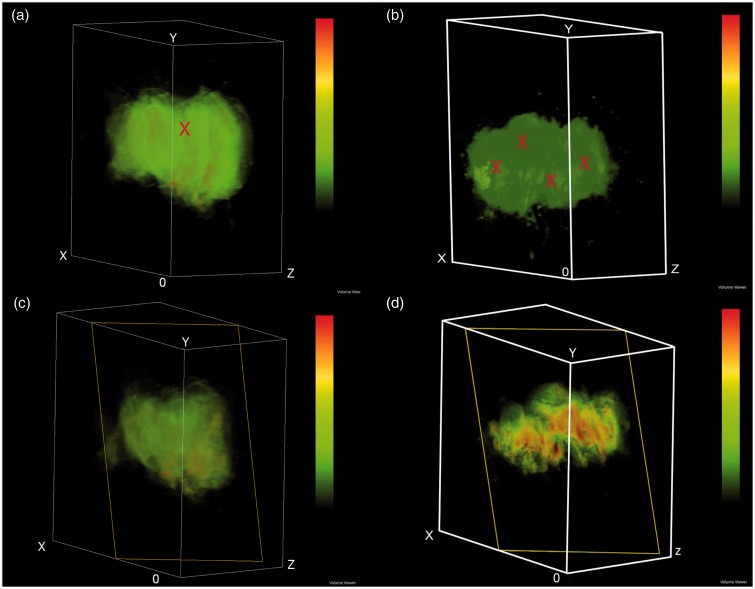

3D reconstruction of fluorescence images (Figure 4) was carried out to evaluate intratumoral distribution of SN-38 from the single injection at low dose (2.2 mg) and double injections at high dose (9.7 mg). The green color represents low concentration of SN-38, whereas yellow and red colors represent higher SN-38 concentration, respectively. High concentration of SN-38 was found surrounding the injection site and the concentration was gradually decreased when moving further away from the injection site. Results clearly showed that double injections at high dose provided promising results as SN-38 distributed to most of tumor area. Interestingly, tumors in the double injections at high dose showed a bimodal distribution pattern resulting from multiple injections of depots.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of fluorescent images of single injection at low dose (a, b) and double injections at high does (c, d). (a and c) Superficial image in pseudocolor and (b and d) Sagittal section in pseudocolor: Voxel size is 2.4 × 2.4 × 10.8 mm3 for single injection at low dose and 2.4 × 2.4 × 1.6 mm3 for double injections at high dose. Low SN-38 signal represented by green color. The symbol “X” in (a) and (c) represents injected sites. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Tumor histology

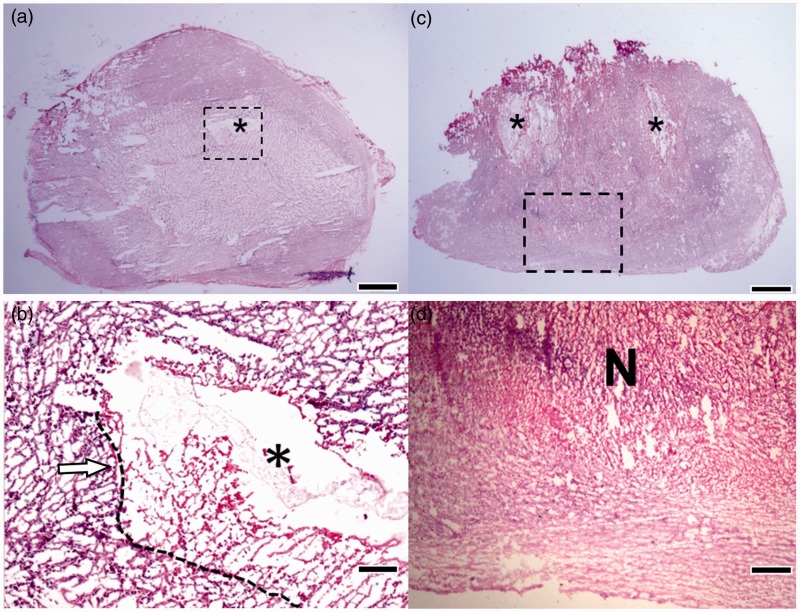

H&E staining was used to analyze the histology of tumor tissues. After seven days of injection, the control group (Figure 5(a)) showed loose pattern of tumor cells caused by hypoxia in the center while tumor cells were denser around the tumor boundary. The dashed line represented the boundary between necrotic region and available gliomas cells (left side of the dashed line). Different GBM features including necrosis area, perivascular infiltration, and multinucleated giant cells (indicated by arrows in Figure 5(b)) were observed. Moreover, hypoxia core with reticular endothelial cells were also founded. The presence of neutrophils in an outer area of tumor indicated mild inflammatory response. Pseudopalisade pattern (gliomas with necrotic foci surrounded with hypercellular zones) in tumors of the control group was also observed. Pseudopalisade cells express high level of vascular endothelial growth factor. When the gliomas cells go into asphyxia condition caused by poor angiogenesis, they tend to migrate to oxygen-rich area and leave necrosis-like area behind. Hence, GBM with pseudopalisade cells has more aggressive behavior than other types of tumors.28 This tumor model had all common characteristics of gliomas including dense packing, high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and presence of mitosis activity. These characteristics can be observed in all tumor samples with non-treatment group and incompletely treated tumors.

Figure 5.

H&E sections of tumor tissues. (a, b) Control group: Low (a) and high (b) (dashed square area) magnification. The injection sites of depots are indicated by the symbol “*”. Dashed line in B indicates the boundary of available gliomas cells and necrotic region. Arrow indicates perivascular infiltration and multinucleated giant cells; (c, d) Double injections at high dose: Low (c) and high (d) magnification. The area that tumor cells lost their nuclei structure and necrosis/karyolysis was marked as “N”. The symbol “*” shows the injection site. Scale bars are 2 mm in (a) and (c), 100 µm in (b), and 300 µm in (d). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

For tumors that received double injections at high dose, H&E staining indicated necrotic and karyolysis cells caused by SN-38 toxicity. The nuclei dissolution near the depot site also suggested the diffusion of SN-38 from the depots to tumor cells (Figure 5(c) and (d)). Lower ischemic necrotic area of tumors in the control group compared to that of the double injections at high dose was observed by histological analysis. It should be noted that using SN-38 as chemotherapeutic agents took advantages of hypoxia and acidic environment inside tumors allowing higher accumulation of SN-38 due to poorly lymphatic drainage of tumor. The other advantage is that acidic condition in hypoxic area promoted the activation of lactone ring of SN-38, making it more toxic.29 Additionally, polymeric depots system could provide a protection for encapsulated drug and maintain it activated along the release period.18

Tumors that received double injections at high dose showed significantly smaller tumor volume than the other groups. Moreover, its normalized area of cell death was the highest. Histological analysis confirmed the tumor response to SN-38 at cellular level, where the vast area of necrotic characteristic replaced the viable tumor cells area. Although, this study demonstrates efficient cancer treatment by local delivery of SN-38-loaded depots, small fraction of viable tumor cells possibly by pseudopalisade (a unique characteristic of grade IV GBM)28 could be observed at the edge of tumors. Subsequently, it may possibly develop recurrent tumors. To overcome this problem, multiple injections of SN-38 loaded PLECs depot are suggested to maximize therapeutic efficiency and minimize the risk of recurrence.30

In summary, as we hypothesized that an increase in dose or the injection site would result in more distribution of SN-38 covering the tumor area, results confirmed this hypothesis in that it showed more ischemic liquefactive necrosis caused by the toxicity of SN-38 released from depots. Antitumor efficacy study and histopathological analysis confirmed the use of SN-38-loaded depots for tumor treatment.

Conclusion

This work demonstrates antitumor efficacy and intratumoral distribution of SN-38 released from polymeric depots inside U-87MG xenograft tumor model in nude mice. These depots were successfully injected into tumors at different doses and number of injection. Results showed that an increase in injection positions and doses resulted in the suppression of tumor growth and larger cell death area. The distance of distribution and 3D reconstruction method were also used to evaluate intratumoral distribution of SN-38. Results from this work suggest that the system could be used for interstitial drug delivery for GBM or neurological diseases.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by Mahidol University, Thailand. The financial support for Ketpat Vejjasilpa from the Center of Excellence for Innovation in Chemistry (PERCH-CIC) is gratefully acknowledged. The third author would like to acknowledge the Thailand Research Fund through the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program (Grant No. PHD/0126/2554).

Author contributions

NN developed and designed the experimental concept. VK conducted fluorescent imaging and simulation model. MC performed tumor preparation. LN advised on histopathology analysis. NN and VK interpreted data and wrote manuscript.

References

- 1.Brat DJ. Glioblastoma: biology, genetics, and behavior. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2012, pp. 102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folkman J, Long D. The use of silicone rubber as a carrier for prolonged drug therapy. J Surg Res 1964; 139: 42–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnyder A, Huwyler J. Drug transport to brain with targeted liposomes. NeuroRx 2005; 2: 99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James CD. Nanoparticles for treating brain tumors: unlimited possibilities. Neuro Oncol 2012; 14: 389–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng W, Kallinteri P, Walker DA, Parker TL, Garnett MC. Evaluation of poly(glycerol-adipate) nanoparticle uptake in an in vitro 3-D brain tumor co-culture model. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007; 232: 1100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabathuler R. Blood-brain barrier transport of drugs for the treatment of brain diseases. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2009; 8: 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie J, Wang CH. Electrospun micro- and nanofibers for sustained delivery of paclitaxel to treat C6 glioma in vitro. Pharm Res 2006; 23: 1817–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dang W, Daviau T, Brem H. Morphological characterization of polyanhydride biodegradable implant gliadel during in vitro and in vivo erosion using scanning electron microscopy. Pharm Res 1996; 13: 683–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buahin KG, Judy KD, Hartke C, Domb AJ, Maniar M, Colvin OM, Brem H. Controlled release of 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide from the fatty acid dimer-sebacic acid copolymer. Polym Adv Tech 1992; 3: 311–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judy KD, Olivi A, Buahin KG, Domb A, Epstein JI, Colvin OM, Brem H. Effectiveness of controlled release of a cyclophosphamide derivative with polymers against rat gliomas. J Neurosurg 1995; 82: 481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sapra P, Zhao H, Mehlig M, Malaby J, Kraft P, Longley C, Greenberger LM, Horak ID. Novel delivery of SN38 markedly inhibits tumor growth in xenografts, including a camptothecin-11-refractory model. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 1888–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xuan T, Zhang JA, Ahmad I. HPLC method for determination of SN-38 content and SN-38 entrapment efficiency in a novel liposome-based formulation, LE-SN38. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2006; 41: 582–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodds HM, Haaz MC, Riou JF, Robert J, Rivory LP. Identification of a new metabolite of CPT-11 (irinotecan): pharmacological properties and activation to SN-38. J Pharm Exp Ther 1998; 286: 578–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivory LP, Chatelut E, Canal P, Mathieu-Boue A, Robert J. Kinetics of the in vivo interconversion of the carboxylate and lactone forms of irinotecan (CPT-11) and of its metabolite SN-38 in patients. Cancer Res 1994; 54: 6330–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuroda J, Kuratsu J, Yasunaga M, Koga Y, Saito Y, Matsumura Y. Potent antitumor effect of SN-38-incorporating polymeric micelle, NK012, against malignant glioma. Int J Cancer 2009; 124: 2505–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiniger SC, Kreuter J, Khalansky AS, Skidan IN, Bobruskin AI, Smirnova ZS, Severin SE, Uhl R, Kock M, Geiger KD, Gelperina SE. Chemotherapy of glioblastoma in rats using doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles. Int J Cancer 2004; 109: 759–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolhatkar RB, Swaan P, Ghandehari H. Potential oral delivery of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxy-camptothecin (SN-38) using poly(amidoamine) dendrimers. Pharm Res 2008; 25: 1723–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manaspon C, Hongeng S, Boongird A, Nasongkla N. Preparation and in vitro characterization of SN-38-loaded, self-forming polymeric depots as an injectable drug delivery system. J Pharm Sci 2012; 101: 3708–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nittayacharn P, Manaspon C, Hongeng S, Nasongkla N. HPLC analysis and extraction method of SN-38 in brain tumor model after injected by polymeric drug delivery system. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2014; 239: 1619–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasongkla N, Boongird A, Hongeng S, Manaspon C, Larbcharoensub N. Preparation and biocompatibility study of in situ forming polymer implants in rat brains. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2012; 23: 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boongird A, Nasongkla N, Hongeng S, Sukdawong N, Sa-Nguanruang W, Larbcharoensub N. Biocompatibility study of glycofurol in rat brains. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011; 236: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khamlao W, Hongeng S, Sakdapipanich J, Nasongkla N. Preparation of self-solidifying polymeric depots from PLEC-PEG-PLEC triblock copolymers as an injectable drug delivery system. J Polym Res 2012; 19: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasongkla N, Boongird A, Hongeng S, Manaspon C, Larbcharoensub N. Preparation and biocompatibility study of in situ forming polymer implants in rat brains. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2012; 23: 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faustino-Rocha A, Oliveira PA, Pinho-Oliveira J, Teixeira-Guedes C, Soares-Maia R, da Costa RG, Colaco B, Pires MJ, Colaco J, Ferreira R, Ginja M. Estimation of rat mammary tumor volume using caliper and ultrasonography measurements. Lab Anim (NY) 2013; 42: 217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krupka TM, Weinberg BD, Wu H, Ziats NP, Exner AA. Effect of intratumoral injection of carboplatin combined with pluronic P85 or L61 on experimental colorectal carcinoma in rats. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007; 232: 950–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012; 9: 676–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerretsen M, Schrijvers AH, van Walsum M, Braakhuis BJ, Quak JJ, Meijer CJ, Snow GB, van Dongen GA. Radioimmunotherapy of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenografts with 131I-labelled monoclonal antibody E48 IgG. Br J Cancer 1992; 66: 496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brat DJ, Castellano-Sanchez AA, Hunter SB, Pecot M, Cohen C, Hammond EH, Devi SN, Kaur B, Van Meir EG. Pseudopalisades in glioblastoma are hypoxic, express extracellular matrix proteases, and are formed by an actively migrating cell population. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 920–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Ghandi A, Liebes L, Louie SG, Hofman FM, Schonthal AH, Chen TC. Effective conversion of irinotecan to SN-38 after intratumoral drug delivery to an intracranial murine glioma model in vivo. Laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg 2011; 114: 689–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu W, MacKay JA, Dreher MR, Chen M, McDaniel JR, Simnick AJ, Callahan DJ, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A. Injectable intratumoral depot of thermally responsive polypeptide-radionuclide conjugates delays tumor progression in a mouse model. J Control Release 2010; 144: 2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]