Abstract

We reported recently that after a nutritional growth retardation, rats showed significant weight gain, central fat accumulation, dyslipidemia, and β-cell dysfunction during a catch-up growth (CUG) phase. Here, we investigated whether glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) ameliorated the rapid weight gain, central fat deposition, and β-cell dysfunction during the CUG in rats. Sixty-four male Sprague Dawley rats were stratified into four groups including normal control group, CUG group, catch-up growth with liraglutide treatment group, and catch-up growth with liraglutide and exendin 9–39 treatment group. Energy intake, body weight, and body length were monitored. Fat mass percentage was analyzed by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry scan. Plasma triglyceride and non-esterified fatty acid were measured. The β-cell mass was analyzed by morphometric analysis and signaling molecules were examined by Western blot and real-time PCR. Insulin secretion capability was evaluated by hyperglycemic clamp test. Liraglutide prevented weight gain and improved lipid and glucose metabolism in rats under CUG conditions, which were associated with reduced fasting insulin levels and improved glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Improved β-cell function is found to be associated with increased β-cell replication as determined by β-cell density and insulin-Ki67 dual staining. Furthermore, liraglutide increased islet pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1 (Pdx-1) and B-cell lymphoma-2 transcript and protein expression, and reduced Procaspase-3 transcript and Caspase-3 p11 subunit protein expression, suggesting that expression of Pdx-1 and reduction of apoptosis may be the mechanisms involved. The therapeutic effects were attenuated in rats co-administered with exendin 9–39, suggesting a GLP-1 receptor-dependent mechanism. These studies revealed that incretin therapy effectively prevented fast weight gain and β-cell dysfunction in rats under conditions of nutrition restriction followed by nutrition excess, which is in part due to enhanced functional β-cell mass and insulin secretory capacity.

Keywords: Catch-up growth, liraglutide, β-cell dysfunction, GLP-1

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone released from the L cells of intestine in response to nutrient ingestion.1 GLP-1 has a variety of biological effects. In pancreatic islets, GLP-1 stimulates insulin secretion while suppresses glucagon release in a glucose-dependent manner.1,2 GLP-1 promotes insulin synthesis and gene expressions.3,4 Moreover, GLP-1 stimulates β-cell replication and suppresses β-cell apoptosis under β-cell-injury conditions, which lead to enhanced functional β-cell mass at least in rodents5–7 and possibly in human as well.8 GLP-1-induced enhancement of β-cell mass may present a conceivable explanation underlying the incretin therapy that prevented or delayed the onset of type 2 diabetes in mice.7 Clinical studies showed that in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients, the GLP-1 secretion or action is impaired, which is exemplified by the decreased postprandial GLP-1 secretion.7,8 Given its additional extrapancreatic actions including regulation of food intake and suppression of hepatic glucose production, GLP-1 has been proposed for treating T2DM9 and potentially its complications.10 GLP-1 has short half-life (1–2 min) due to rapid enzymatic degradation by dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP4), therefore the DPP4 resistant long-lasting GLP-1 analogs or agonists have thus been developed and are clinically used for treating obese diabetic patients.11

There is a tremendous increase in the prevalence of T2DM in newly developed and developing countries particularly since the past 30 years.12 This is obviously attributed to the excessive energy intake as well as nutritional transitions in these populations.13 This phenomenon, particularly, the rapid growth after a transient growth retardation is relevant to a condition clinically termed as “catch-up” growth that commonly leads to increased risks for metabolic diseases in adulthood.14

Catch-up growth (CUG) is characterized by an accelerated growth rate following a period of growth retardation mainly caused by acute malnutrition or severe illness.15 Epidemiological evidences suggest that catch-up growth in adult (CUGA) is an important causative factor for the widespread insulin resistance-related diseases such as T2DM and obesity, especially in developing countries.16–19 The underlying molecular mechanisms, however, remain unclear. The fat overaccumulation, particularly more central lipid distribution, as referred to as “catch-up fat” phenotype may contribute to the development of insulin resistance during the “catch-up growth course.”19 Our recent observations showed that the nutrition promotion after undernutrition facilitates lipid overaccumulation causing dyslipidemia and insulin resistance in adult CUG rats.20 Moreover, the β-cell and entero-insular axis function was found to be significantly impaired in these CUG rats,21,22 suggesting that the CUG-related T2DM is in part contributed by β-cell and entero-insular axis dysfunction.

Liraglutide, a long-acting GLP-1 analog, is currently clinically used for treating obesity and diabetes. In this study, we aimed to determine whether this GLP-1 analogue exerts protective effects on prevention of catch-up fat and β-cell dysfunction under catch-up growth conditions in rats.

Materials and methods

Animals

Six-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats (n = 64; weight range 200–230 g) were purchased from the Tongji Experimental Animal Center, Wuhan, China. All animals were caged individually in a climate-controlled environment (temperature, 22 ± 1℃; relative humidity, 60%) with a 12-h light/dark cycle. The animals were fed with a standard chow diet (24% protein, 66% carbohydrates, and 10% fat) or high fat diet (HFD) (21% protein, 59% fat, and 20% carbohydrates) with free access to tap water. Total 64 rats were used after one-week adaptation to their housing environment and followed up to the regimens of feeding and treatment as described in Figure 1. All procedures complied with guidelines were approved by the institutional animal care committee.

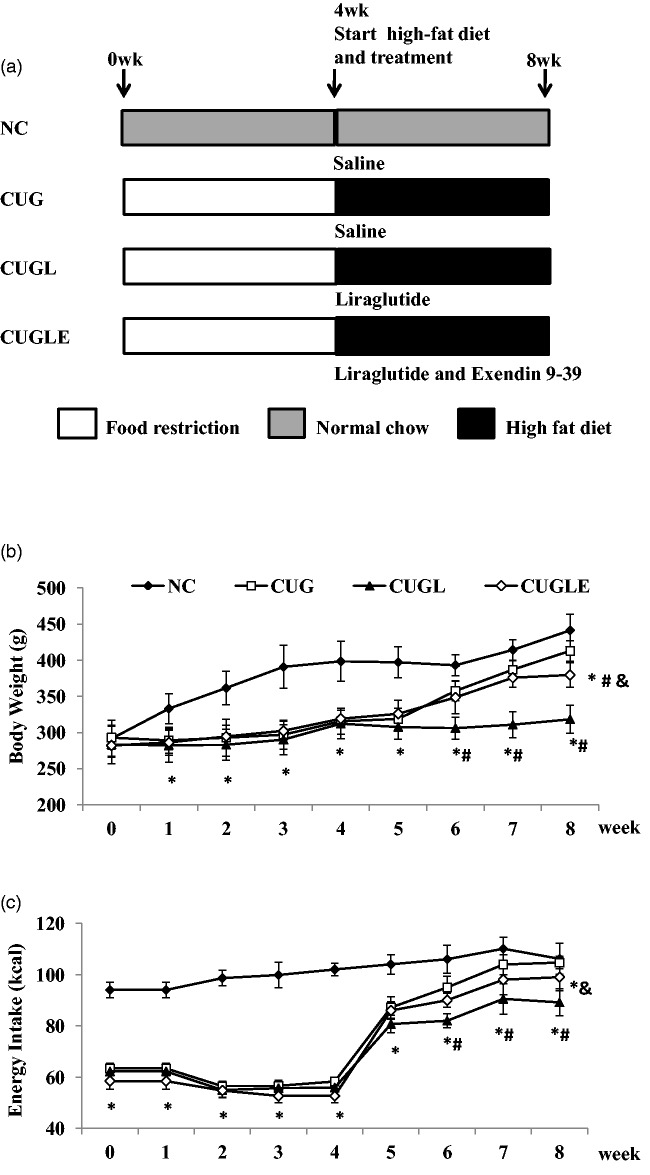

Figure 1.

(a) Diagram of the experimental design. Rats were divided into the normal chow diet group (NC, n = 16), the catch-up growth after caloric restriction group (CUG, n = 16), the catch-up growth after caloric restriction with liraglutide treatment group (CUGL, n = 16), and the catch-up growth after caloric restriction with both liraglutide and exendin (9–39) treatment group (CUGLE, n = 16). (b) Body weight of rats in each group at the end of every week. (c) Energy intake per day of rats in each group at the end of every week. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *p < 0.01 versus the NC group; #p < 0.01 versus the CUG group; &p < 0.01 versus the CUGL group

Animal model of CUG and treatment regimens

Seven-week-old rats (n = 64) were randomly divided into a normal chow group (NC group; n = 16) and a food restriction group (n = 48) (Figure 1). The NC group was fed ad libitum a standard chow diet as described before, whereas the food restriction group was fed with 60% of their normal chow intake for four weeks. At the end of the fourth week of food restriction phase, the food restriction group was further divided into three groups and received different treatments: one was given 0.9% saline (200 µg kg−1, i.h., Bid) (CUG group, n = 16), one was given liraglutide (Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen, Denmark) (200 µg/kg, i.h., Bid) (catch-up growth with liraglutide treatment [CUGL] group, n = 16), and the other was given liraglutide and exendin 9–39 (CG55285, Raybiotech, Atlanta, USA) mixture (liraglutide 200 µg/kg, Ex9–39 100 µg/kg, i.h., Bid) (catch-up growth with liraglutide and exendin 9–39 [CUGLE] group, n = 16). The NC group also started to receive 0.9% saline (200 µg/kg, i.h., Bid). At the same time, all the rats in CUG, CUGL, and CUGLE groups were re-fed with a HFD consisting (by energy) of 21% protein, 59% fat, and 20% carbohydrates. After four weeks of re-feeding, all 16 rats in each group were decapitated. Changes in energy intake per day, body weight, and body length were determined once a day. Lee index was calculated as an index of obesity in rodents.20 Lee index = weight 1/3 (in g) × 1000/nasoanal length (in cm).

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan

At the end of week 4 and 8, eight rats in each group were anesthetized by sodium pentobarbital (35 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, USA) and body composition was measured using whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scanning (DEXA; GE Linar Corp., Madison, WI).

Plasma biochemical profiles

Plasma samples were collected in eight rats from each group after overnight fasting at the end of week 8. Triacylglycerol and non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) were measured using commercial kit (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China).

Islet isolation

Pancreatic islets were isolated as previously described.23 Briefly, eight rats in each group were fasted for 15 h and anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital. After cardiac puncture, the pancreas was immediately removed and perfused in Krebs–Ringer solution. Then the pancreas was cut and digested by collagenase P (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The solution was incubated in a 37℃ water bath for homogenizing, and the islets were collected under a stereomicroscope. Then RNA and protein of islets were extracted for further use as described below.

Hyperglycemic clamp test

Hyperglycemic clamp tests were performed to evaluate the glucose-stimulated insulin secretory function of β-cells as described previously.24 Briefly, eight rats in each group were overnight fasted at week 8, and tail artery and vein were cannulated with intravenous integrated catheters (24G × 19 mm) filled with heparin-saline solution (50 IU heparin/mL).20 The arterial and venous catheters were used for blood sampling and intravenous infusion, respectively. After an equilibrium with saline (−60 to 0 min), glucose was given as an intravenous bolus of 375 mg/kg over a 1-min interval and was subsequently infused as a 25% (wt/vol) solution in the amount needed to keep the plasma concentration at 11 mM. Blood samples were collected at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60 min to measure insulin and glucose levels. Insulin was measured by a radioimmunoassay kit (Ninetripods, Tianjing, China). Blood glucose was measured using a glucometer (One Touch Ultra, Lifescan, Milpitas, CA, USA).

Oral glucose tolerance test and insulin releasing test

At the end of week 8, an oral glucose tolerance was performed in eight rats from each group. The rats were fasted for 15 h, and the basal blood sample was collected. Then, the rats were gavaged with glucose (2.0 g/kg) and additional blood samples were collected at t = 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. Both glucose and insulin concentrations were measured in all blood samples. Plasma glucose was measured by a glucometer (One Touch Ultra, Lifescan, Milpitas, CA). Plasma insulin level was estimated by an insulin ELISA kit (EMD Millipore, Missouri, USA).

Immunohistochemistry analysis of β-cell mass, individual β-cell size, β-cell density, and β-cell proliferation

Eight rats from each group were euthanized by sodium pentobarbital, and the pancreas was immediately isolated, weighed, fixed, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were double stained by immunohistochemistry for insulin and Ki67 as previously described.22 Briefly, for insulin, slides were incubated in mouse anti-insulin IgG (1:100; Maixin_Bio, Fujian, China) followed by peroxidase-3,3′-diaminobenzidine-conjugated gout anti-mouse IgG (Maixin_Bio, Fujian, China). For Ki67, slides were incubated in rabbit anti-Ki67 monoclonal antibody (1:100; Maixin_Bio, Fujian, China) followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated gout anti-rabbit IgG (Maixin_Bio, Fujian, China). Pancreatic images were visualized using a microscope equipped with a digital camera (Coolpix 950, Nikon, Japan) and the Image ProPlus Software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). The relative area of β-cells was determined as the ratios between insulin-stained cells and the total area, expressed as percentages. Pancreatic β-cell mass was determined by multiplying the relative β-cell area by the pancreas weight.22,23 The individual β-cell size was calculated via dividing the β-cell area by the number of nuclei. However, the actual β-cell number is probably higher than the number counted since not all β-cells are sectioned across their nuclei, and the β-cell size may be overestimated.25 β-cell density was determined by dividing the number of β-cell nuclei by total pancreas area.25 Proliferative islet β-cells were expressed as the average percentage of Ki67+ β-cell per islet.23

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from islets of eight rats in each group, using the RNAprep pure tissue kit (DP431, Tiangen biotech, Beijing, China) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA by the TIANscript RT kit (KR104-02, Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. SYBR green-based RT-PCR was conducted in triplicate to evaluate gene expression using ABI prism 7900 RT-PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Data were normalized to the relative levels of β-actin mRNA transcripts in the same experiment and analyzed by ABI PRISM SDS 2.1 software.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| Genes | Forward primers (5′–3′) | Reverse primers (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Pdx-1 | GAGGACCCGTACAGCCTACA | CGTTGTCCCGCTACTACGTT |

| Bcl-2 | GGTGGTGGAGGAACTCTTCA | ATGCCGGTTCAGGTACTCAG |

| Procaspase-3 | GGACCTGTGGACCTGAAAAA | GACCCGTCCCTTGAATTTCT |

| β-actin | CGTTGACATCCGTAAAGAC | TGGAAGGTGGACAGTGAG |

Primer sequences for RT-PCR.

Western blot analysis

Protein extracts from islets (20 µg from each rat) were subjected to Western blot analysis using mouse antipancreatic duodenal homeobox-1 (Pdx-1) monoclonal antibody (1:800; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), mouse anti-Caspase-3 p12 subunit monoclonal antibody (1:500, Boster Bio-Engineering, China), mouse anti-B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2) polyclonal antibody (1:800, Bioworld, USA), and mouse anti-GAPDH antibody (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Detection of primary antibodies was performed using HRP-conjugated relevant secondary antibodies (1:15,000, Boster Bio-Engineering, China) and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Statistical analysis

To compare the early phase β-cell secretion function among each group, an empirical index was determined as the insulin/glucose incremental area ratio of the first 30 min during oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (ΔAUCI30/ΔAUCG30). The index shows the ability of β-cell to increase its release rate in response to the glycemic stimulus during the early phase.26 All data were presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test with SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Liraglutide attenuated fast weight gain in CUG rats

Rats showed tardy growth during a transient nutrition restriction, and upon re-feeding by HFD, rats rapidly gained body weight (Figure 1(b)), associated with steeply increased energy intake (Figure 1(c)). Body length also increased after re-feeding, but relatively slow compared to body weight (Figure 2(a)), which resulted in a much higher Lee index of CUG rats compared to control rats at the end of week 8 (Figure 2(b)). Liraglutide treatment significantly reduced weight gain during the CUG, which was partially attenuated by co-administration of exendin 9–39 (Figure 1(b)). Interestingly, liraglutide did not prevent food intake in the first week of re-feeding; it however significantly decreased food intake in the remaining feeding course (Figure 1(c)), consistent with its weight sparing effects. Exendin 9–39 significantly attenuated the liraglutide’s effects on food intake (Figure 1(c)), suggestive of GLP-1 receptor dependency. The body length of CUGL rats increased more slowly than CUG rats after re-feeding, but without any significance (Figure 2(a)). At week 8, Lee index of CUGL rat was similar to NC rat, which was significantly lower than CUG and CUGLE rats (Figure 2(b)).

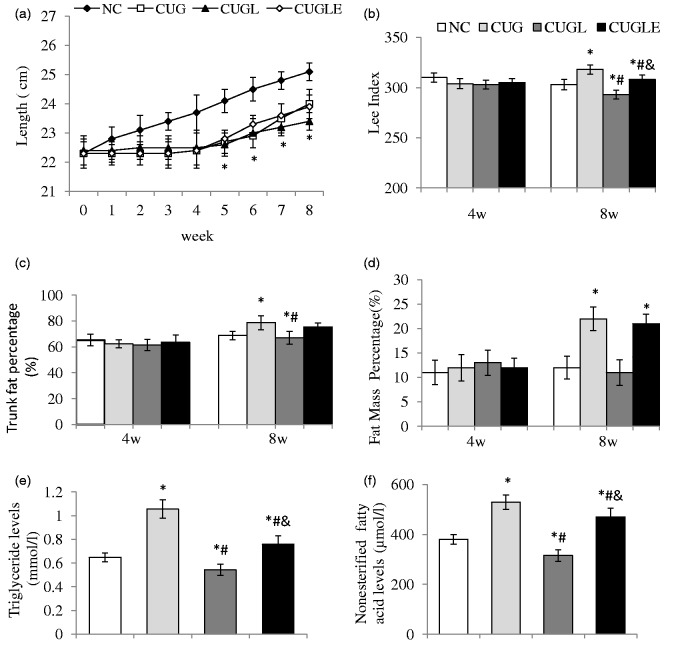

Figure 2.

(a) Body length of rats in each group at the end of every week. (b) Lee index of rats at the end of week 4 and 8. (c) Trunk fat percentage and (d) fat mass percentage analyzed by DEXA at the end of week 4 and 8. (e) Fasting plasma triglyceride (TG) and (f) fasting plasma non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) levels were determined at the end of week 8. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8 in each group. *p < 0.01 versus the NC group; #p < 0.01 versus the CUG group; &p < 0.01 versus the CUGL group

Liraglutide prevented central obesity in CUG rats

At the end of week 4 and 8, we measured total body fat mass percentage (Figure 2(d)) and trunk fat percentage (Figure 2(c)) of eight rats in each group via DEXA scan. At week 4, body composition of all rats was the same. However, after four weeks of re-feeding, CUG rats showed significantly higher fat mass percentage and trunk mass percentage than NC ones. With liraglutide treatment, CUGL rats avoided such central fat deposition, while exendin 9–39 significantly attenuated the liraglutide’s effects in CUGLE rats, suggesting of GLP-1 receptor dependency.

Liraglutide improved triglyceride (TG) and NEFA profiles in CUG rats

Four-week caloric restriction resulted in an approximately 20% lower circulation of TG and NEFA levels in rats (Figure 2(e) and (f)). Upon CUG by re-feeding with HFD, rats had 1.6-fold increase in plasma TG and NEFA levels. The increment of the plasma TG and NEFA was completely prevented by liraglutide treatment, which however was significantly antagonized by the co-treatment with exendin 9–39, suggesting that the beneficial effects of liraglutide in lowering plasma lipids were GLP-1 receptor dependent.

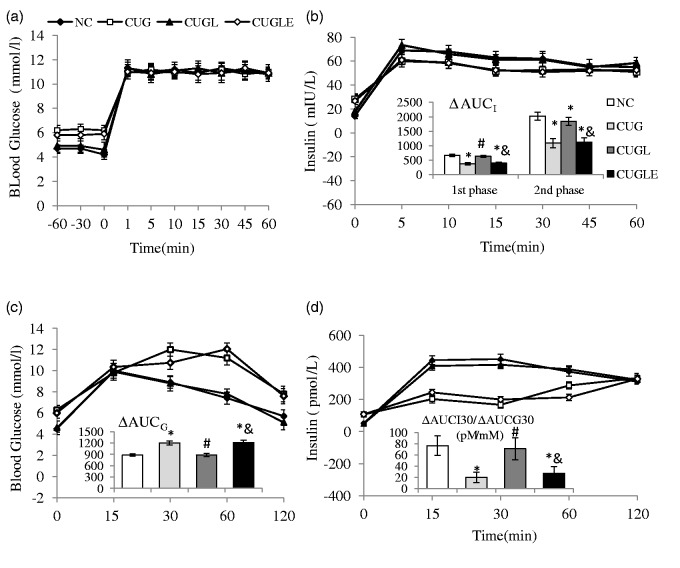

Liraglutide protected glucose tolerance and increased insulin secretion during the OGTT in CUG rats

After four weeks of catch-up, the HFD re-fed rats had impaired glucose tolerance, comparing to controls (Figure 3(c) ΔAUCG of CUG versus ΔAUCG of NC, 1202 ± 77 mmol/L*min versus 898 ± 65 mmol/L*min, p < 0.01). Liraglutide protected glucose tolerance (ΔAUCG for CUGL 892 ± 75 mmol/L*min, p < 0.01 versus CUG), which was also interfered by exendin 9–39 co-infusion (ΔAUCG for CUGLE 1204 ± 74 mmol/L*min, p < 0.01 versus both NC and CUGL). The early phase insulin releasing ability of HFD re-fed rats was also injured (Figure 3(d) ΔAUCI30/ΔAUCG30 for CUG versus NC 19.9 ± 9.1 pmol/mmol versus 77.5 ± 17.4 pmol/mmol, p < 0.01). Liraglutide prevented insulin secretion damage (ΔAUCI30/ΔAUCG30 for CUGL 73.0 ± 19.6 pmol/mmol, p < 0.01 versus CUG) in a GLP-1 receptor-dependent manner (ΔAUCI30/ΔAUCG30 for CUGLE 27.2 ± 11.9 pmol/mmol, p < 0.01 versus both NC and CUGL).

Figure 3.

Effects of HFD catch-up growth and liraglutide treatment on β-cell. (a) Blood glucose levels during the clamp. (b) Insulin levels and first- and second-phase incremental area under the curve of insulin secretion (ΔAUCI) during the hyperglycemic clamp. (c) Blood glucose levels and incremental AUC of glucose levels (ΔAUCG) during the OGTT. (d) Insulin levels of OGTT and insulin/glucose incremental area ratio of the first 30 min during OGTT (ΔAUCI30/ΔAUCG30). All the results are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.01 versus the NC group; #p < 0.01 versus the CUG group; &p < 0.01 versus the CUGL group

Liraglutide improved β-cell secretion function in CUG rats

To assess whether the insulin secretion capacity after the four-week CUG feeding course in the rats treated with liraglutide is superior to those untreated rats, we analyzed insulin responses via hyperglycemia clamp studies in vivo, during which glucose was infused to maintain glycemia at ∼11 mmol/L for 60 min (Figure 3(a)).

In the HFD re-fed rats, significantly higher plasma glucose concentrations relative to controls were detected during the basal period (−60 to 0 min, Figure 3(a)). Liraglutide treatment maintained similar glucose levels of CUGL rats as controls in a GLP-1 receptor-dependent manner (Figure 3(a)). However, after delivery of intravenous glucose bolus, identical glucose levels were achieved among all groups.

The insulin levels of HFD re-fed rats after glucose bolus were still less than controls, both for acute incremental rise (Figure 3(b) first phase ΔAUCinsulin for CUG versus NC rats 337.75 ± 41.3 mIU min/L versus 665.5 ± 36.5 mIU min/L, p < 0.01) and second phase incremental rise (Figure 3(b) first phase ΔAUCinsulin for CUG versus NC rats 1088.6 ± 160 mIU min/L versus 2017.7 ± 135 mIU min/L, p < 0.01). Liraglutide infusion sheltered CUGL rats from impaired insulin secretion (first phase ΔAUCinsulin for CUGL rats 628.8 ± 38.2 mIU min/L, second phase ΔAUCinsulin for CUGL rats 1842.45 ± 136 mIU min/L, both p < 0.01 versus CUG rats)) via GLP-1 receptor (first phase ΔAUCinsulin for CUGLE rats 393.9 ± 42 mIU min/L, second phase ΔAUCinsulin for CUGLE rats 1128.9 ± 145 mIU min/L, all p < 0.01 versus NC and CUGL rats).

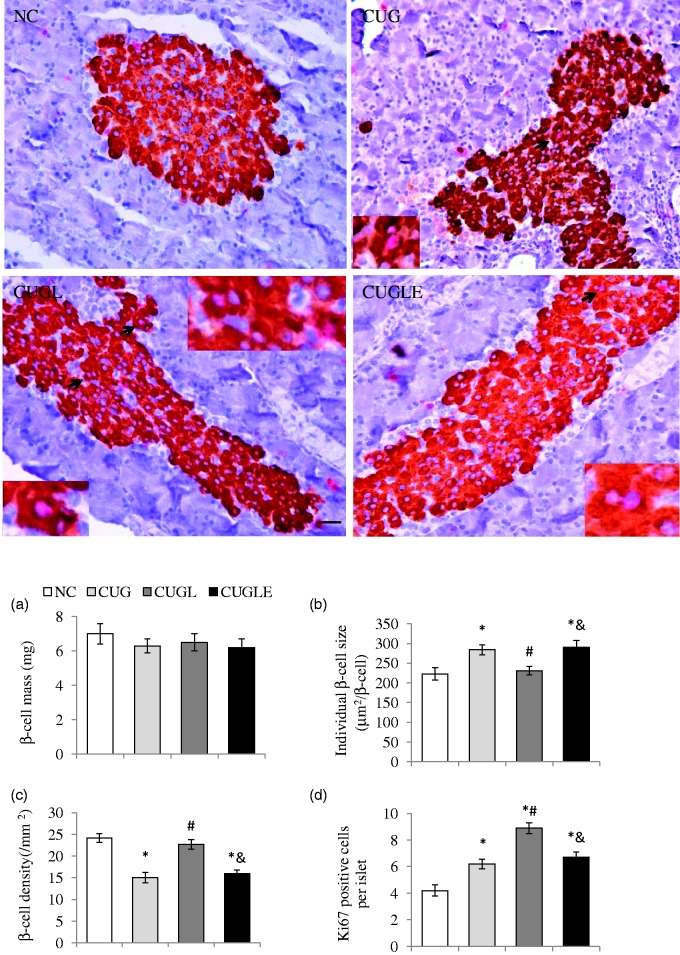

Liraglutide promoted β-cell replication and survival in CUG rats

Upon four-week CUG by HFD feeding, rats showed significant expansion in the β-cell mass, which was comparable to controls. Liraglutide treatment did not show further enhancement of the β-cell mass in these CUG rats (Figure 4(a)). Pancreatic staining for Ki67 showed that caloric restriction decreased Ki67+ β-cell numbers in islets (Figure 4(d)), whereas the CUG during HFD re-feeding significantly increased Ki67+ β-cells (Figure 4(d)). It is noticeable that liraglutide treatment yields a further 43.5% increase in Ki67+ islet β-cells, which was however, diminished by exendin 9–39 co-administration (Figure 4(d), p < 0.01). Considering that while the dynamic of the β-cell mass is controlled by the rate of β-cell growth and death, both β-cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia can both contribute to the expansion of β-cell mass, we thus examined β-cell density and β-cell size in liraglutide untreated or treated CUG rats. As shown, treatment with liraglutide significantly increased β-cell density (Figure 4(c) CUGL versus CUG 22.7 ± 1.1 versus 15 ± 1.2, p < 0.01) while maintaining their normal β-cell size (Figure 4(b), CUGL versus CUG: 231 ± 11 versus 284 ± 13, p < 0.01) compared with untreated HFD re-fed rats. The results indicate that the enhancement of β-cell mass in the CUG rats was mainly contributed by β-cell hypertrophy, whereas with liraglutide treatment, the augment of β-cell mass was contributed by increment of β-cell number as the consequence of increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis. This implies that the enlargement of β-cell mass in liraglutide-treated rats may have superior secretory function compared with untreated rats under CUG conditions.

Figure 4.

Effects of HFD catch-up growth and liraglutide treatment on β-cell morphology and proliferation (400 × magnification, scale bar 50 µm). Double staining of insulin and Ki67 in rat pancreas islet were carried out, and (a) β-cell mass, (b) individual β-cell size, and (c) β-cell density were calculated. (d) The average numbers of Ki67+β-cells per islet were determined. All the results are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.01 versus the NC group; #p < 0.01 versus the CUG group; &p < 0.01 versus the CUGL group. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

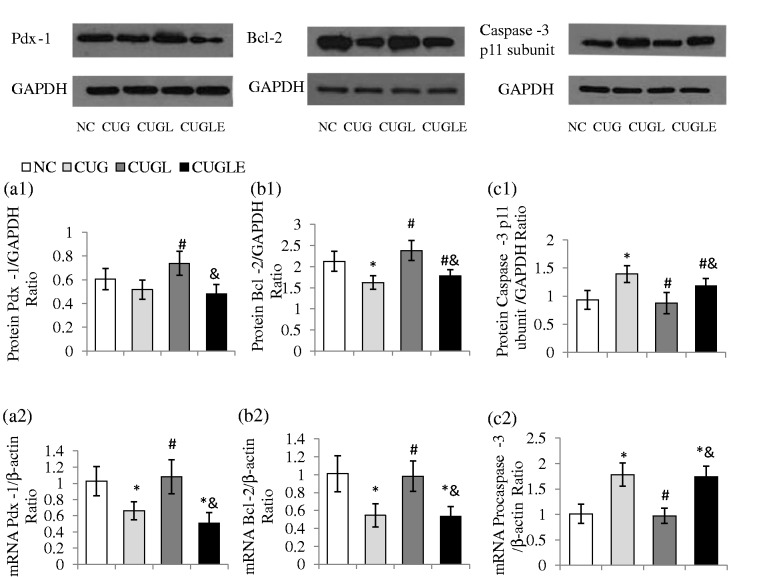

The β-cell survival was evaluated by examining islet expression of Caspase-3 p12 subunit and Bcl-2 expressions at protein levels as well as Procaspase-3 and Bcl-2 at transcripts levels. RT-PCR showed increased islet Procaspase-3 but reduced Bcl-2 transcripts in the CUG rats, whereas liraglutide treatment reduced islet Procapase-3 mRNA while increased Bcl-2 mRNA expression (Figure 5(b2) and (c2), both p < 0.01). Consistently, Western blot analysis showed that the CUG rats displayed increased islet Caspase-3 p12 subunit protein but reduced Bcl-2 protein expressions (Figure 5(b1) and (c1), both p < 0.01). Remarkably, the liraglutide treatment significantly reduced islet Caspase-3 p12 subunit protein but increased Bcl-2 protein expressions comparing to untreated CUG rats (both p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Effects of HFD catch-up growth and liraglutide treatment on β-cell function and apoptosis. Pdx-1 protein (a1) and mRNA (a2) levels of islets at the end of week 8. Pdx-1 protein levels of islets were assessed by Western blot and the results were expressed as the ratios of Pdx-1 and GAPDH. The Pdx-1 mRNA levels were detected by qPCR and expressed as the ratios of Pdx-1 and β-actin. Protein levels of Bcl-2 (b1) and Caspase-3 p 12 subunit (c1) were detected by Western blot and the results were expressed as the ratios of Caspase-3 p12 subunit or Bcl-2 with GAPDH. The mRNA levels of Bcl-2 (b2) and Procaspase-3 (c2) were expressed as the ratios of Proaspase-3 or Bcl-2 with β-actin. All the results are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.01 versus the NC group; #p < 0.01 versus the CUG group; &p < 0.01 versus the CUGL group

Liraglutide increased islet cell Pdx-1 expression in CUG rats

It has been previously shown that Pdx-1 expression is essential for integrating GLP-1R-dependent signals in regulating islet β-cell growth, survival, and function.45 We thus evaluated the β-cell Pdx-1 expression by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis using isolated islets. As shown, during the CUG, the pancreatic Pdx-1 expression levels both at protein (Figure 5(a1), p > 0.05) and transcript (Figure 5(a2), p < 0.01) were decreased compared to the control rats. Remarkably, liraglutide treatment significantly increased Pdx-1 transcript and protein expressions (CUGL versus CUG, both p < 0.01), which however was attenuated by exendin 9–39 co-administration (CUGL versus CUGLE, both p < 0.01).

Discussion

Our data demonstrated that after a temporary period of growth retardation through caloric restriction and a subsequent excessive nutrient feeding, the CUG rats displayed a rapid weight gain, central fat tissue accumulation, hyperlipidemia, elevated fasting insulin levels, and islet β-cell dysfunction. Remarkably, the rats receiving daily injections of liraglutide during the CUG showed weight sparing effects, prevented central fat deposition, improved lipid profiles, reduced fasting insulin levels, and improved β-cell glucose competence, suggesting that the incretin therapy provided beneficial effects in ameliorating metabolic disorders and β-cell dysfunction caused by excessive nutrients feeding during the CUG.

Numerous clinical studies suggested that CUG early in life is a major risk factor for later obesity, insulin resistance, T2DM, and the complications associated with this disease.17–19 Our recent preclinical studies showed that the CUG after food restriction led to declined insulin secretion function, which is associated with reduced L cells number and lower plasma GLP-1 concentration in CUG rats.22 Under such nutrition excess after nutrition restriction conditions, rats had elevated circulation cholesterol and free fatty acids, and the dyslipidemia as a chronic oxidative stressor appears as an contributor to the development of islet β-cell dysfunction.22 Our current observations are consistent with our previous findings, and the outcome of this study further provided evidence supporting a notion that disturbance of the entero-insular axis as a consequence of declined GLP-1 secretion and β-cell dysfunction may be responsible for the increased risk of metabolic disorders during CUG after food restriction in rodents.21 Since GLP-1 has both β-cell trophic effects and extrapancreatic effects, the improved metabolic conditions in the CUG rat might also be contributed by the incretin-mediated improvement of lipid metabolism.27

Notably, the CUG rats, whether they received liraglutide daily injections or not, showed significantly increased β-cell mass. The enlarged β-cell mass in both groups was volumetrically comparable. However, further morphometric analysis showed that the increased β-cell mass of untreated CUG rats was mainly due to β-cell hypertrophy, whereas the liraglutide-treated rats showed increase in β-cell number, as a consequence of increased β-cell proliferation and reduced apoptosis. Regulation of functional β-cell mass homeostasis either by increasing or decreasing is an important mechanism in the control of glucose homeostasis.28 In the early development of insulin resistance and diabetes, an appropriate enhancement of functional β-cell mass appears to be sufficient to prevent the onset of diabetes in rodent diabetes models7,28,29 and potentially in humans with this disease.30,31 However, the observations of β-cell hypertrophy together with elevated fasting insulin levels suggest that the untreated CUG rats attempted to enhance their β-cell function to compensate the increasing demand for insulin due to excessive nutrition intake caused by insulin resistance. Unfortunately, the enlargement of β-cell volume alone seemed not enough to compensate for the increasing metabolic demands. Moreover, since the β-cell hypertrophy is often associated with impaired β-cell secretion function32 and decreased gene expressions for insulin and some crucial transcription factors including Pdx-1,33 the β-cell hypertrophy in CUG rats may lead to β-cell decompensation and finally a profound reduction in β-cell mass.34

In our study, we also observed that the enhanced β-cell mass in liraglutide-treated CUG rats was associated with increased β-cell proliferation as determined by pancreatic insulin-Ki67 dual staining and decreased β-cell apoptosis as evaluated by islet Bcl-2 and Caspase-3 levels. Although the degree of enhanced β-cell mass in liraglutide-treated CUG rats was comparable with those of untreated rats, pancreata morphometric analysis showed that the liraglutide-treated rats displayed increased β-cell density per islet area. This suggests that the incretin enhances functional β-cell mass through stimulation of β-cell replication, which may provide beneficial effects to these rats in the context of β-cell functions. This notion is at least in part supported by our hyperglycemic clamp data showing that liraglutide-treated rats had improved insulin secretory function in response to glucose challenge. Increased β-cell mass and turnover by incretin therapy is well documented in rodents, and it appears an important mechanism underlying incretin effects in preventing diabetic hyperglycemia in diabetes-prone animals.7,28,29 Autonomously, the enhancement of β-cell mass is obvious in rodents, particularly under physiological conditions such as pregnancy35 or under obese insulin resistant conditions.7 Studies using human autopsy pancreas showed that β-cell mass remarkably increased with obesity.36 However, it is worth to note that the β-cell replication is only detectable in lean humans but not in obese humans.36 The explanation behind why the CUG rats showed enlarged β-cell mass without increased β-cell replication is unclear. It is presumably the obesity-associated dyslipidemia that may act as a β-cell stress factor which somehow suppresses β-cell growth.37

Our finding suggests that liraglutide provides beneficial effects in improving metabolic status and β-cell function in CUG rats which is mediated by GLP-1 receptor as the GLP-1 receptor antagonist exendin 9–39 significantly attenuated the effects of liraglutide. Activation of GLP-1 receptor leads to activation of signaling pathway involving PI3K/Akt7,38 and its potential downstream molecule Pdx-1.39 Pdx-1 is a transcription factor essential for fetal pancreogenesis40,41 as well as differentiation and maturation of adult islet cells through regulating genes including insulin, glucokinase, and GLUT2.42 Previous studies showed that activation of Pdx-1 is essential for mediating GLP-1 action on promotion of β-cell growth, survival, the expansion of β-cell mass, and β-cell function.1,43–45 Our observations that liraglutide treatment increased Pdx-1 expression in islets from CUG rats may be in part responsible for GLP-1 receptor-mediated pancreatic beneficial effects, namely the enlargement of functional β-cell mass and improved insulin secretory capacity under nutrition excess conditions.

Treatment with liraglutide showed significant weight sparing effects, prevented central fat deposition, and improved lipid profiles in rats during HFD CUG after food restriction which are consistent with other studies in normal and obese animals46 as well as in human with T2DM.47 Mild to moderate nausea and vomiting are the main side effects of liraglutide, which are often transient. Although nausea may contribute to weight loss, the combined effects on energy intake and energy expenditure are the most widely accepted mechanisms for liraglutide caused weight control.48

Liraglutide treatment improved β-cell glucose competence exemplified by increased insulin secretion during a hyperglycemic clamp test compared with untreated CUG rats which showed elevated fasting insulin levels but declined first-phase and second-phase insulin secretion during the course of glucose infusion. It is known that declined first-phase insulin secretion is an early sign of β-cell dysfunction.49 In a CUG mouse model, mice that underwent low birth weight due to maternal malnutrition showed basal hyper-secretion of insulin but completely lack responsiveness to glucose during the CUG feeding course.50 It is interesting to note that the rats in the early stage of CUG (i.e. at one week re-feeding) after a two-week semi-starvation showed basal hyper-secretion of insulin but yet maintained β-cell glucose responsiveness as determined by the in situ pancreas perfusions and in isolated islet perfusion test,51 suggesting the duration of CUG determines the deteriorating extent of β-cell function. The impaired β-cell glucose competency appears in part contributed by accelerated rate of fat deposition named catch-up fat.51 A long-term increase of NEFA elevates the basal insulin level and blunts islet response to glucose.52 Significantly elevated NEFA levels were found in HFD-fed (this study) and normal chow-fed CUG rats, associated with increased ROS accumulation,22 which causes mitochondria stress and ultimately leads to β-cell apoptosis.53,54 Importantly, the incretin therapy ameliorated these defects in CUG rats.

In the present study, we observed that liraglutide preserved β-cell function and have a beneficial effect in weight control of the CUGA rats. Moreover, both effects of liraglutide were GLP-1 receptor dependent. However, we were not able to distinguish whether the β-cell protection effect of liraglutide was directly regulated via GLP-1 receptor in β-cells or indirectly regulated via body weight control. A recent published paper that studied the neuronal or visceral nerve-specific Glp1r knock-out in mice with liraglutide treatment found that the body weight suppressive effect of liraglutide was eliminated by neuronal Glp1r deletion.56 Meanwhile, there was still an improvement in glucose tolerance under liraglutide treatment.55 However, in their study, islet function was assessed by evaluation of insulin level after a glucose challenge at only one time point, which is the 15-min time point. Thus, they do not find the effect of liraglutide on insulin secretion and fail to assess the impact of the neuronal Glp1r deletion on β-cells function. Further study is needed for us to clarify the direct and indirect effects of liraglutide on β-cell function by using either neuronal and/or β-cell-specific Glp1r knock-out CUGA model.

In conclusion, the present study investigated the effects of liraglutide, the long-lasting GLP-1 analog, on HFD-induced CUG rats. Our studies revealed that CUG rats displayed a rapid weight gain, fast central fat accumulation, hyperlipidemia, elevated fasting insulin levels, and islet β-cell dysfunction, while the rats receiving liraglutide treatment during the CUG showed weight sparing effects, prevented central fat deposition, improved lipid profiles, reduced fasting insulin levels, and improved β-cell glucose competence, suggesting that incretin therapy effectively prevented fast weight gain and β-cell dysfunction in HFD-induced CUG rats, and the underlying mechanisms include enhanced functional β-cell mass and insulin secretion capacity. Further research is required to compare other T2DM therapies with GLP-1 analog in CUG models, which may help us find a more promising protection strategy for adults undergoing CUG.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (#81100562/H0711 and #30771035/H0711). Research in the Wang lab was supported by Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR), and Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA).

Author contributions

Participated in research design: JZ and L-LC. Conducted experiments: TC, YZ, H-QL, X-LD, J-YZ. Contributed analytic tools and data analysis: TC. Performed data collection and interpretation: TC, JZ, L-LC. Contributed in manuscript writing: TC, JZ, Q-HW.

References

- 1.Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab 2006; 3: 153–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald PE, El-kholy W, Riedel MJ, Salapatek AMF, Light PE, Wheeler MB. The multiple actions of GLP-1 on the process of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 2002; 51: S434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drucker DJ, Philippe J, Mojsov S, Chick WL, Habener JF. Glucagon-like peptide I stimulates insulin gene expression and increases cyclic AMP levels in a rat islet cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987; 84: 3434–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alarcon C, Wicksteed B, Rhodes CJ. Exendin 4 controls insulin production in rat islet beta cells predominantly by potentiation of glucose-stimulated proinsulin biosynthesis at the translational level. Diabetologia 2006; 49: 2920–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptides: regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Mol Endocrinol 2003; 17: 161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buteau J, Foisy S, Joly E, Prentki M. Glucagon-like peptide 1 induces pancreatic β-cell proliferation via transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Diabetes 2003; 52: 124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Q, Brubaker P. Glucagon-like peptide-1 treatment delays the onset of diabetes in 8 week-old db/db mice. Diabetologia 2002; 45: 1263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farilla L, Bulotta A, Hirshberg B, Calzi SL, Khoury N, Noushmehr H, Bertolotto C, Mario UD, Harlan DM, Perfetti R. Glucagon-like peptide 1 inhibits cell apoptosis and improves glucose responsiveness of freshly isolated human islets. Endocrinology 2003; 144: 5149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2006; 368: 1696–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D, Luo P, Wang Y, Li W, Wang C, Sun D, Zhang R, Su T, Ma X, Zeng C, Wang H, Ren J, Cao F. Glucagon-like peptide-1 protects against cardiac microvascular injury in diabetes via a cAMP/PKA/Rho-dependent mechanism. Diabetes 2013; 62: 1697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, Schmidt WE, Montanya E, Brett JH, Zychma M, Blonde L. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet 2009; 374: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon KH, Lee JH, Kim JW, Cho JH, Choi YH, Ko SH, Zimmet P, Son HY. Epidemic obesity and type 2 diabetes in Asia. Lancet 2006; 368: 1681–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S, Park CH, Jang JS. Antecedent intake of traditional Asian-style diets exacerbates pancreatic β-cell function, growth and survival after Western-style diet feeding in weaning male rats. J Nutr Biochem 2006; 17: 307–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong KK, Ahmed ML, Emmett PM, Preece MA, Dunger DB. Association between postnatal catch-up growth and obesity in childhood: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2000; 320: 967–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prader A, Tanner JM, Von Harnack GA. Catch-up growth following illness or starvation: an example of developmental canalization in man. J Pediatr 1963; 62: 646–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Victora CG, Barros FC. Commentary: the catch-up dilemma—relevance of Leitch’s ‘low–high’ pig to child growth in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 2001; 30: 217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker DJP, Hales CN, Fall CHD, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PMS. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia 1993; 36: 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotteveel J, van Weissenbruch MM, Twisk JW, Delemarre-Van WHA. Infant and childhood growth patterns, insulin sensitivity, and blood pressure in prematurely born young adults. Pediatrics 2008; 122: 313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dulloo AG. Regulation of fat storage via suppressed thermogenesis: a thrifty phenotype that predisposes individuals with catch-up growth to insulin resistance and obesity. Horm Res Paediatr 2008; 65: 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen LL, Hu X, Zheng J, Kong W, Zhang HH, Yang WH, Zhu SP, Zeng TS, Zhang JY, Deng XL, Hu D. Lipid overaccumulation and drastic insulin resistance in adult catch-up growth rats induced by nutrition promotion after undernutrition. Metabolism 2011; 60: 569–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen LL, Yang WH, Zheng J, Hu X, Kong W, Zhang HH. Research effect of catch-up growth after food restriction on the entero-insular axis in rats. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010; 7: 45–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen LL, Yang WH, Zheng J, Zhang JY, Yue L. Influence of catch-up growth on islet function and possible mechanisms in rats. Nutrition 2011; 27: 456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soltani N, Qiu H, Aleksic M, Glinka Y, Zhao F, Liu R, Li Y, Zhang N, Chakrabarti R, Ng T, Jin T, Zhang H, Lu W, Feng Z, Prud’homme G, Wang Q. GABA exerts protective and regenerative effects on islet beta cells and reverses diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 11692–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henquin JC, Nenquin M, Stiernet P, Ahren B. In vivo and in vitro glucose-induced biphasic insulin secretion in the mouse pattern and role of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and amplification signals in β-cells. Diabetes 2006; 55: 441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald PE, Joseph JW, Yau D, Diao J, Asghar Z, Dai F, Oudit GY, Patel MM, Backx PH, Wheeler MB. Impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, enhanced intraperitoneal insulin tolerance, and increased β-cell mass in mice lacking the p110γ isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Endocrinology 2004; 145: 4078–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrannini E, Mari A. Beta cell function and its relation to insulin action in humans: a critical appraisal. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 943–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouwens L, Rooman I. Regulation of pancreatic beta-cell mass. Physiol Rev 2005; 85: 1255–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tourrel C, Bailbe D, Meile MJ, Kergoat M, Portha B. Glucagon-like peptide-1 and exendin-4 stimulate β-cell neogenesis in streptozotocin-treated newborn rats resulting in persistently improved glucose homeostasis at adult age. Diabetes 2001; 50: 1562–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu G, Stoffers DA, Habener JF, Bonner-Weir S. Exendin-4 stimulates both beta-cell replication and neogenesis, resulting in increased beta-cell mass and improved glucose tolerance in diabetic rats. Diabetes 1999; 48: 2270–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garber AJ. Long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists. A review of their efficacy and tolerability. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: S279–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovshin JA, Drucker DJ. Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2009; 5: 262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan CB, MacPhail RM, Sheu L, Wheeler MB, Gaisano HY. Beta-cell hypertrophy in fa/fa rats is associated with basal glucose hypersensitivity and reduced SNARE protein expression. Diabetes 1999; 48: 997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laybutt DR, Glandt M, Xu G, Ahn YB, Trivedi N, Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC. Critical reduction in β-cell mass results in two distinct outcomes over time adaptation with impaired glucose tolerance or decompensated diabetes. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 2997–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S. Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes. Diabetes 2004; 53: S16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rieck S, Kaestner KH. Expansion of β-cell mass in response to pregnancy. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2010; 21: 151–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saisho Y, Butler AE, Manesso E, Elashoff D, Rizza RA, Butler PC. β-Cell mass and turnover in humans effects of obesity and aging. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 111–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donath MY, Ehses JA, Maedler K, Schumann DM, Ellingsgaard H, Eppler E, Reinecke M. Mechanisms of β-cell death in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2005; 54: S108–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Q, Li L, Xu E, Wong V, Rhodes C, Brubaker PL. Glucagon-like peptide-1 regulates proliferation and apoptosis via activation of protein kinase B in pancreatic INS-1 beta cells. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 478–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elghazi L, Balcazar N, Bernal-Mizrachi E. Emerging role of protein kinase B/Akt signaling in pancreatic β-cell mass and function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2006; 38: 689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jonsson J, Carlsson L, Edlund T, Edlund H. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature 1994; 371: 606–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoffers DA, Zinkin NT, Stanojevic V, Clarke WL, Habener JF. Pancreatic agenesis attributable to a single nucleotide deletion in the human IPF1 gene coding sequence. Nat Genet 1997; 15: 106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Habener JF, Stoffers DA. A newly discovered role of transcription factors involved in pancreas development and the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 110: 12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perfetti R, Zhou JIE, Doyle ME, Egan JM. Glucagon-like peptide-1 induces cell proliferation and pancreatic-duodenum homeobox-1 expression and increases endocrine cell mass in the pancreas of old, glucose-intolerant rats. Endocrinology 2000; 141: 4600–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buteau J, Roduit R, Susini S, Prentki M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 promotes DNA synthesis, activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and increases transcription factor pancreatic and duodenal homeobox gene 1 (Pdx-1) DNA binding activity in beta (INS-1)-cells. Diabetologia 1999; 42: 856–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Cao X, Li LX, Brubaker PL, Edlund H, Drucker DJ. β-Cell Pdx1 expression is essential for the glucoregulatory, proliferative, and cytoprotective actions of glucagon-like peptide-1. Diabetes 2005; 54: 482–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsen PJ, Fledelius C, Knudsen LB, Tang-Christensen M. Systemic administration of the long-acting GLP-1 derivative NN2211 induces lasting and reversible weight loss in both normal and obese rats. Diabetes 2001; 50: 2530–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryan GJ, Foster KT, Jobe LJ. Review of the therapeutic uses of liraglutide. Clin Ther 2011; 33: 793–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manning S, Pucci A, Finer N. Pharmacotherapy for obesity: novel agents and paradigms. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2014; 5: 135–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerich JE. Is reduced first-phase insulin release the earliest detectable abnormality in individuals destined to develop type 2 diabetes? Diabetes 2002; 51: S117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jimenez-Chillaron JC, Hernandez-Valencia M, Reamer C, Fisher S, Joszi A, Hirshman M, Oge A, Walrond S, Przybyla R, Boozer C, Goodyear LJ, Patti ME. β-Cell secretory dysfunction in the pathogenesis of low birth weight-associated diabetes: a murine model. Diabetes 2005; 54: 702–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Casimir M, de Andrade PB, Gjinovci A, Montani JP, Maechler P, Dulloo AG. A role for pancreatic beta-cell secretory hyperresponsiveness in catch-up growth hyperinsulinemia: relevance to thrifty catch-up fat phenotype and risks for type 2 diabetes. Nut Metab (Lond) 2011; 8: 2–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yaney GC, Corkey BE. Fatty acid metabolism and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 2003; 46: 1297–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pi J, Zhang Q, Fu J, Woods CG, Hou Y, Corkey BE, Collins S, Andersen ME. ROS signaling, oxidative stress and Nrf2 in pancreatic beta-cell function. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2010; 244: 77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newsholme P, Haber EP, Hirabara SM, Rebelato ELO, Procopio J, Morgan D, Oliveira-Emilio HC, Carpinelli AR, Curi R. Diabetes associated cell stress and dysfunction: role of mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial ROS production and activity. J Physiol 2007; 583: 9–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sisley S, Gutierrez-Aguilar R, Scott M, D’Alessio DA, Sandoval DA, Seeley RJ. Neuronal GLP1R mediates liraglutide’s anorectic but not glucose-lowering effect. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 2456–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]