Abstract

Optical mapping of Ca2+-sensitive fluorescence probes has become an extremely useful approach and adopted by many cardiovascular research laboratories to study a spectrum of myocardial physiology and disease conditions. Optical mapping data are often displayed as detailed pseudocolor images, providing unique insight for interpreting mechanisms of ectopic activity, action potential and Ca2+ transient alternans, tachycardia, and fibrillation. Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes and optical mapping systems continue to evolve in the ongoing effort to improve therapies that ease the growing worldwide burden of cardiovascular disease. In this technical review we provide an updated overview of conventional approaches for optical mapping of Cai2+ within intact myocardium. In doing so, a brief history of Cai2+ probes is provided, and nonratiometric and ratiometric Ca2+ probes are discussed, including probes for imaging sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ and probes compatible with potentiometric dyes for dual optical mapping. Typical measurements derived from optical Cai2+ signals are explained, and the analytics used to compute them are presented. Last, recent studies using Cai2+ optical mapping to study arrhythmias, heart failure, and metabolic perturbations are summarized.

Keywords: calcium cycling, calcium fluorescence, calcium imaging, calcium mapping

calcium (Ca2+) is the primary ion associated with the activation and modulation of contraction in cardiac myocytes (10). Intracellular calcium (Cai2+) measurements from myocardial tissue are critical for understanding the physiology of excitation-contraction (EC) coupling and mechanisms of disease. High-fidelity Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes provide for high temporal resolution measurements of Cai2+ transients, which are generated by processes associated with a sudden increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and subsequent reduction of cytosolic Ca2+. For the most part, the Cai2+ transient represents sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release and SR Ca2+ resequestration (55). Optical mapping is often used to image the fluorescence of a Ca2+ probe administered to myocardial tissue to measure spatial changes in the kinetics and amplitude of Cai2+ transients (52, 70, 72, 106). Additional insights into the mechanisms of EC coupling are provided when optical mapping of a Ca2+ probe is combined with other modes of optical mapping, such as imaging of a potentiometric dye to measure action potentials (20), and is particularly useful for studying pathological mechanisms, including arrhythmogenesis, within living myocardial tissue (32, 49, 78).

There are excellent reviews of Cai2+ cycling in cardiac cells (10, 48, 117) and Cai2+ imaging of single cardiac myocytes (13). Salama and Hwang have also provided a detailed review of Cai2+ optical mapping that focuses on dual mapping of action potentials and Cai2+ transients (82). The objective of the present review is to provide an updated overview of conventional approaches for optical mapping of Cai2+ within intact myocardium. In doing so, a brief history of Cai2+ probes is provided, and nonratiometric and ratiometric Ca2+ probes are discussed, including probes for imaging SR Ca2+ and probes compatible with potentiometric dyes for dual optical mapping. Typical measurements derived from optical Cai2+ signals are explained and the analytics used to compute them are presented. Last, recent studies using Cai2+ optical mapping to study arrhythmias, heart failure, and metabolic perturbations are summarized.

Cai2+ Fluorescence Probes

A variety of light-emitting compounds have been used to image intracellular Ca2+ within myocardial tissue. In recent work, these include ratiometric and nonrationmetric probes, genetically expressed probes, and low-affinity Ca2+ probes to image SR Ca2+ (Table 1). Aequorin was one of the first light-emitting compounds used to study Cai2+ in muscle cells (12, 25, 79). It was isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria and is bioluminescent blue when bound to Ca2+, as Shimomura et al. reported in 1963 (86). Aequorin is a photoprotein that emits light by an intramolecular reaction and does not require optical excitation, minimizing complications of cellular autofluorescence. It does not localize to intracellular compartments but also does not pass freely across the sarcolemma, requiring microinjection or disruption of the sarcolemma for intracellular measurements (25). Other limitations are that it emits less than one photon per molecule, and its light-emitting component (coelenterazine) is irreversibly consumed to produce light, requiring that it be added to the media to maintain luminescence (67).

Table 1.

Properties of common Ca2+ probes used to study cardiac physiology

| Excitation, nm |

Emission, nm |

Quantum Yield |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Ca2+ free | Ca2+ bound | Ca2+ free | Ca2+ bound | Ca2+ free | Ca2+ bound | Kd, nM* | |

| Ratiometric | Fura 2 | 362 (330–393) | 335 (311–358) | 512 (476–590) | 505 (467–559) | 0.23 | 0.49 (35) | 135–224 |

| Fura 4F | 362 (330–393) | 335 (311–358) | 512 (476–590) | 505 (467–559) | 770–1,160 (118) | |||

| Indo 1 | 349 (315–372) | 331 (303–354) | 485 (441–538) | 410 (375–488) | 0.38 | 0.56 (35) | 250–844 | |

| Nonratiometric | Rhod 2 | 553 (535–568) | 576 (561–601) | 0.102 (65) | 570–720 | |||

| Fluo 4 | 494 (478–507) | 516 (502–541) | 0.14 | 345 | ||||

| Fluo 2MA | 494 | 516 | 390 | |||||

| Fluo 4FF | 494 | 516 | 9,700 | |||||

| Fluo 2LA | 494 | 516 | 6,700 | |||||

| Genetic | GCaMP2 | 485–487 | 508 | 0.53 (3); 0.93 (96) | 545 ± 32 (3) | |||

| GCaMP3 | 497 | 500–550 | 0.65 (3) | 405 ± 9 (3) | ||||

| SR Ca2+ | ||||||||

| Imaging | Mag-fura 2 | 362 (330–393) | 335 (311–358) | 512 (476–590) | 505 (467–559) | 25,000 | ||

| Mag-fluo-4 | 494 | 516 | 22,000 | |||||

| Fluo 5N | 494 | 516 | 90,000 | |||||

Wavelengths at the spectral peaks of excitation and emission are provided followed by the half-maximum bandwidth in parentheses, when available.

Dissociation constants (Kd) are listed as a range: the lower value is dye in solution and the higher value is the dye in a cell.

In the 1980s Tsien developed fluorescent probes based on tetracarboxylate chelators for Ca2+ that could enter cells by passing through the sarcolemma and not be consumed when emitting light (103), two properties required for imaging Cai2+ from myocardial tissue. Quin 2, a highly selective Ca2+ indicator derived from fluorescent quinoline (100, 101), was one of these early probes. Esterification (explained below) enabled quin 2 to enter and remain within cells. Its fluorescence (339 nm excitation, 492 nm emission) increased fivefold between Ca2+-free and Ca2+-saturated states (101). The drawbacks of quin 2 were that the excitation and emission wavelengths were short and overlapped with cellular autofluorescence [primarily NAD(P)H], the quantum yield was low (0.03–0.14), and only fluorescence intensity changed with changes in Cai2+, making ratiometry impossible (see below). For these reasons quin 2 was considered to be an interim tetracarboxylate chelator probe (103).

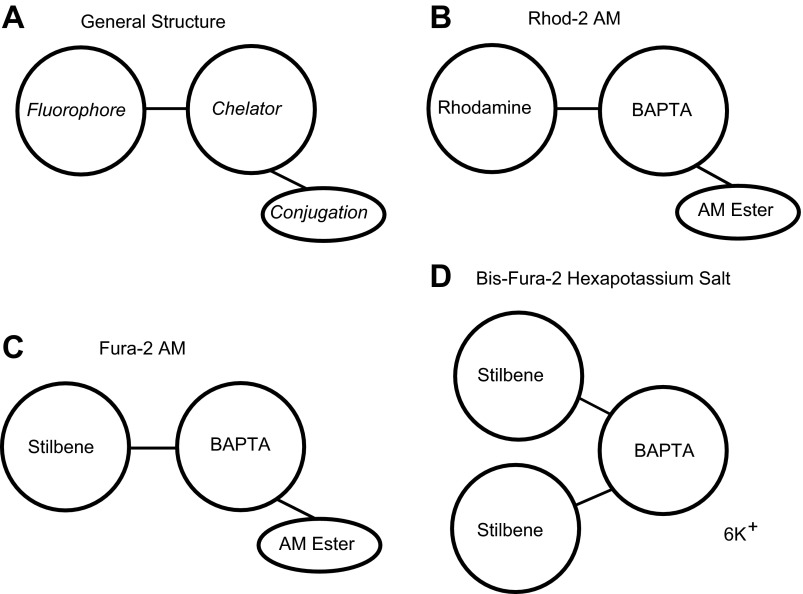

Subsequent work by Tsien and colleagues (35, 102) resulted in the 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) chelator and probes (indo 1, fura 1, fura 2, and fura 3) with significantly enhanced quantum efficiency, improved photobleaching stability, longer excitation wavelengths, improved selectivity for Ca2+, and shifts in wavelength upon Ca2+ binding to enable ratiometry. By 1989 probes based upon the chromophores rhodamine (rhod 2) and fluorescein (fluo 1, fluo 2, and fluo 3) were developed to have lower Ca2+ affinity to aid in imaging cytosolic Ca2+ transients at higher temporal resolutions (65). These late-generation tetracarboxylate chelators, and their derivatives, have the general form shown in Fig. 1A. They consist of a chelating agent that binds Ca2+ (sometimes up to 5 ions), a fluorescent chromophore (fluorophore), and often acetoxymethyl (AM) esters. The BAPTA chelator (Fig. 1, B–D) is related to EGTA but is less sensitive to changes in pH and has greater selectivity for Ca2+ than for other divalent cations, such as Mg2+ (94, 102).

Fig. 1.

Generalized diagrams of typical Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes. A: the general structure of a probe includes a fluorophore for fluorescence, a chelator for binding Ca2+, and an optional conjugation to allow the probe to cross the cell membrane. The basic structures of rhod 2-acetoxymethyl ester (AM) (B), fura 2-AM (C), and bis-fura 2 (D) are shown. BAPTA, 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid.

Rhod 2 has the BAPTA chelator bound to a tetramethylrhodamine fluorophore (Fig. 1B) and is the probe that is currently most often used for optical mapping of myocardial tissue. An early application of rhod 2 to image myocardial Cai2+ is the perfused rabbit heart experiments of Del Nido and colleagues (72). In addition to its higher specificity for Ca2+ chelating, the chromophore properties of tetramethylrhodamine make it particularly advantageous for simultaneous optical mapping of membrane potential and Cai2+ transients. This is because rhod 2 has a peak excitation band (Table 1) that is similar to the potentiometric dye RH-237 (Table 2), so both probes can be energized with one light source, and the peak emission bands of the two probes have minimal overlap, with almost zero fluorescence signal cross talk between the two probes (20, 82).

Table 2.

Properties of common potentiometric probes used to study myocardial electrophysiology

| Potentiometric Probe | Excitation Peak, nm [environment] | Excitation Range, nm | Emission Peak, nm [environment] | Emission Range, nm | ΔF/F, % | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RH-237 | 544 [EtOH] | 400–680 | 790 [EtOH] | 650–860 | 6 | 34, 68 |

| DI-4-ANEPPS | 475 [membrane bound] | 370–570 | 617 [membrane bound] | 570–850 | 8 | 30 |

| PGH-I | 608 [EtOH] | 880 [EtOH] | 18 | 81 | ||

| DI-4-ANBDQBS | 563 [EtOH] | 500–700 | 820 | 700–900 | 15 | 62 |

EtOH, ethanol.

Ca2+ dissociation constants.

The dissociation constant (Kd) of the Ca2+ chelator (Table 1) influences the fluorescence response kinetics of a probe to Cai2+ concentration changes. Kd should be carefully considered when selecting a Ca2+ probe to minimize the effect of Ca2+-binding and -unbinding kinetics on accurate measurements of changes in Cai2+. Rhod 2 has a Kd of 570–710 nM, a range that provides for acceptable measurements of Cai2+ transients for typical animal species used to study cardiac physiology (43). Kd values for popular Ca2+ probes with their excitation/emission peaks and quantum yields are listed in Table 1. Recent work by Kong and Fast (43) provided an experimental survey of probes with a range of Kd and demonstrated that if a probe's Ca2+ affinity is too high (Kd <570 nM) then the Cai2+ transient duration (CaD) could be misrepresented. For example, for long pacing cycle lengths in the swine left ventricle, CaD measured at a 50% level of recovery was almost 81% longer with high-affinity probes (fluo 4 and fluo 2MA) than with low-affinity probes (fluo 4FF and fluo 2LA) (43). Very-low-affinity probes with extremely high Kd (∼22–90 μM), such as fluo 5N (75, 84, 87) and ratiometric mag-fura 2 (33), have been used to study SR Ca2+ in isolated cardiac myocytes. SR Ca2+ has also been optically mapped in myocardial tissue using mag-fluo 4 (45, 104) and fluo 5N (111). In recent studies, fluo 5N was optically mapped simultaneously with the potentiometric probe RH-237 to study SR Ca2+ loading during action potential alternans and ventricular fibrillation (111).

Ca2+ probe esterification.

Many early experiments studied cellular Cai2+ dynamics in isolated cells using either aequorin or the free acid form of a synthetic Ca2+ probe. These agents were administered to the cytosol using microinjection (e.g., Ref. 16) or disruption of the sarcolemma (e.g., Ref. 25). Of course, imaging Cai2+ within myocardial tissue requires a much more efficient approach for cytosolic delivery of the probe. Mechanical dissociation after low-Ca2+ enzymatic treatment can deliver indo 1 to a large number of isolated myocytes (88), but Ca2+ probe esterification was critical for enabling Cai2+ imaging within myocardial tissue.

Probes with AM esters (Fig. 1, B and C) are denoted with an “AM,” as in rhod 2-AM. The ester neutralizes the charge of the probe to promote its passage across the sarcolemmal membrane. Charge neutralization of a probe comes at a price: the probe can no longer be dissolved in water. Because of this, esterified probes are often dissolved in small volumes of dimethyl sulfoxide and stored in aliquots at −20°C. Before an experiment, the aliquot is thawed and mixed 1:1 with 20% pluronic F-127 (50). Sonication will improve probe dissolution. The dissolved probe mixture is then diluted in a small volume of perfusate media. Camphor oil can also be used for dispersing the probe within the solution. The solution is then administered to the coronary vasculature, either by slow injection or by recirculating perfusate containing the probe.

Once in the cytosol, intrinsic esterases cleave the AM ester, trapping the probe in the cell. Although a majority of the probe will be trapped in the cytosol, some will be extruded by an adenosine-binding cassette protein called multidrug resistant glycoprotein (63). Probe efflux by this glycoprotein is partially inhibited by probenecid, with minimal effect on Cai2+ transients, as shown in macrophages (107, 108). The activity of the glycoprotein is temperature-dependent so probe efflux is reduced by performing experiments at lower temperatures, such as 32°C (63). As explained by Sollott and colleagues (88), limitations of probe esterification include noncytosolic probe compartmentalization, incomplete hydrolysis of the ester, and potential alterations of the spectral properties of the probe. Genetically encoded Ca2+ probes (discussed below), such as GCaMP, address many of these limitations (97).

Probe localization.

Ca2+ probe intracellular localization, organelle and lysosome retention, and intracellular origin of the fluorescence signal can vary with experimental conditions. This is apparent when examining published reports that use rhod 2-AM, such as those of Brandes and Bers (14) and Del Nido et al. (72). Using myocytes from rat heart trabeculae, Brandes and Bers selectively permeabilized the sarcolemmal and mitochondrial membranes. They found that 55% of rhod 2 fluorescence originated from mitochondria and 45% originated from the cytosol (14). In contrast, Del Nido et al. loaded isolated guinea pig myocytes with rhod 2-AM and treated the cells with FCCP to permeabilize the mitochondrial membrane. They observed no significant change in the distribution of rhod 2, indicating that rhod 2 was primarily localized to the cytosol. Furthermore, digitonin was administered, and extensive rhod 2 fluorescence was lost, substantiating that fluorescence was primarily of cytosolic origin (72). Other studies used a cold/warm protocol to load rhod 2-AM in the mitochondria of isolated myocytes to measure beat-to-beat changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ (99). Substantial uptake of rhod 2 and fluo 3 by lysosomes/endosomes was also noted in those studies. Overall, this previous work underscores careful consideration of Ca2+ probe compartmentalization and how it could be influenced by probe concentration and loading conditions, especially duration and temperature.

Quantum yield.

Quantum yield (QY) is an important characteristic of a fluorescence probe and is defined as the probability that an absorbed photon will result in an emitted photon. Higher QY is advantageous because less excitation light and less sensitive imaging equipment are required to achieve acceptable signal quality. However, the QY of a probe and its excitation spectrum are both important to consider when imaging myocardial tissue. For example, rhod 2 (a nonratiometric probe) has a QY of 0.102, and fura 2 (a ratiometric probe) has a Ca2+-bound QY of 0.49 (Table 1). It is usually easier to obtain high-quality rhod 2 signals from the myocardium than fura 2 signals because peak excitation for rhod 2 is in the visible (green) range. Peak excitation for fura 2 is in the ultraviolet range, meaning that it may be more difficult to energize an adequate amount of fura 2. This is because the intensity of UV light sources is usually low, UV light does not penetrate the myocardium as deep as longer wavelengths, and the intensities of UV light required for imaging may damage myocardial tissue.

Genetically encoded probes.

Recent developments in the expression of genetically encoded Ca2+ probes have overcome the limitations of intracellular loading associated with exogeneous Ca2+ probes (46, 116). Genetically encoded probes often provide adequate and stable optical Cai2+ transients for cells throughout the myocardium. The first genetically encoded Ca2+ probe was based on the green fluorescent protein and calmodulin (67). A variant (GCaMP) with higher signal-to-noise ratio and a Kd of 235 nM was reported several years later (71). GCaMP was subsequently improved for in vivo expression in rodents to produce GCaMP2 and was optically mapped to study atrioventricular conduction in anesthetized mice (96). Those studies found that GCaMP2 fluorescence was 45% slower than the fluorescence of rhod 2, indicating the slower fluorescence transition kinetics of GCaMP2. The most recent version, GCaMP3, has increased baseline fluorescence and dynamic range (both by 3-fold) as well as 1.3-fold higher affinity for Ca2+ (97).

Transgenic human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes that stably express GCaMP3 have been used in myocardial grafts (85). These cells were grafted within the infarct of guinea pig hearts, and GCaMP3 fluorescence was optically mapped to provide Cai2+ transients originating exclusively from the graft. In conjunction with the ECG, the graft transients were used to show graft-host coupling in ex vivo perfused heart studies (85). A caveat of these studies was that the fluorescence of blebbistatin interfered with that of GCaMP3 due to overlap of their blue-green emission bands. 2,3-Butanedione monoxime, a less-specific action-myosin ATPase inhibitor, was used in lieu of blebbistatin for some experiments (85). Improved GCaMP variants GCaMP6 and GCaMP7 have been recently introduced but not yet implemented for optical mapping of intracellular Ca2+ (3, 18).

Ratiometry.

Ca2+ fluorescence that is optically mapped from myocardial tissue will vary with location and time. Variations are caused by uneven distribution of the probe within the tissue, heterogeneous tissue structure, nonuniform excitation light intensity, and probe photobleaching and washout (exocytosis). These variations are usually removed by scaling the signal at each pixel to have the same range, as is commonly done for rhod 2 signals, but this scaling also makes it impossible to measure changes in diastolic Cai2+ level and Cai2+ transient amplitudes.

Ratiometry is an approach where the fluorescence ratio at each pixel is computed using the values at two wavelengths. This cancels fluorescence variability common to both wavelengths to provide a signal that is proportional to Cai2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). Ratiometry requires a Ca2+ probe that undergoes a shift in the emission or excitation spectra when bound to Ca2+. For example, indo 1 is an emission ratiometric probe because the peak of its emission spectrum shifts to shorter wavelengths as Ca2+ concentration increases (35). Fura 2 is an excitation ratiometric probe because its excitation peak shifts to shorter wavelengths with increases in Ca2+ concentration (35). Ratiometric probes have an isosbestic wavelength, below which fluorescence increases with Ca2+ and above which fluorescence decreases. The fluorescence ratio of wavelengths below and above the isosbestic point cancels common variability while amplifying the Cai2+ signal.

Microscope systems are used to image ratiometric Ca2+ probes within cells to study cytosolic and organelle Ca2+ concentrations (90). Both excitation ratiometry (59, 61) and emission ratiometry (6, 22, 95) are used in microscopy studies. Ratiometric imaging is not commonly used in myocardial optical mapping studies because of the additional required illumination wavelengths (for excitation ratiometery) or imaging instrumentation (for emission ratiometery). When imaging myocardium, additional instrumentation, if available, is often used to image an additional signal, such as that of a potentiometric probe (36), as discussed below. The additional spectral bandwidth required to perform emission or excitation ratiometry may also overlap with that of other probes or endogeneous compounds, such as myoglobin or NAD(P)H (31, 47, 106). Furthermore, most ratiometric Ca2+ probes are excited by UV light (Table 1), and, as discussed above, providing adequate UV illumination to myocardial tissue to image the fluorescence of a Ca2+ probe over a large area could be challenging.

Even so, an early myocardial imaging study used emission ratiometery (indo 1) to measure changes in Cai2+ at discrete epicardial locations during ischemia in perfused rabbit hearts (54). Since then, ratiometric imaging of indo 1 was used to study the progression of Ca2+ activation across the epicardial surface of perfused rat hearts (23). Recent work has used excitation ratiometry (fura 2) to study changes in diastolic and systolic Cai2+ during ischemia-reperfusion injury (106). Although optical mapping of ratiometric probes is not common, this could change as inexpensive high-power light-emitting diode (LED) light sources, inexpensive high-speed cameras, and new ratiometric Ca2+ probes are developed. For example, fura 4F is a newer ratiometric probe (118) that has a Kd similar to that of rhod 2 (Table 1). Even though fura 4F has not yet been used in optical mapping experiments, sophisticated multiparametric optical mapping systems are being developed for ratiometric imaging of both high- and low-affinity Ca2+ probes (36, 56). Future studies of myocardial metabolism, where changes in Cai2+, mitochondrial redox state, and mitochondrial membrane potential are measured (2, 39, 91, 98), would certainly benefit from accurate measurements of relative changes in Cai2+ using ratiometry.

Quantification of nonratiometric signals.

The nonratiometric probe rhod 2 is optically compatible with RH-237, a popular potentiometric probe, so it is used in many studies that simultaneously map Cai2+ transients and transmembrane potential (20, 69, 70), as discussed below. Rhod 2 signals are often scaled, as explained above, but the fluorescence could be calibrated to accurately measure [Ca2+]i within myocardial tissue (20). A calibration approach was developed by Del Nido and colleagues for perfused rabbit hearts (72) and then used to study arrhythmia mechanisms in subsequent work (7, 19, 20). Measurements of true [Ca2+] using calibrated rhod 2 fluorescence provide valuable physiological insight but also require long-term dye stability, which can be challenging to maintain. Furthermore, calibration of rhod 2 fluorescence depends on the optical absorbance of the dye within the tissue, and that absorbance may differ between species as well as between normal and disease states. Prior experiments are therefore required to determine the characteristics of rhod 2 in each type of tissue. Experiments are also prolonged by additional protocols to measure the full range of [Ca2+]i for calibration of the fluorescence signal. Thus, rhod 2 fluorescence calibration is typically only used for experiments that require measurements of true [Ca2+].

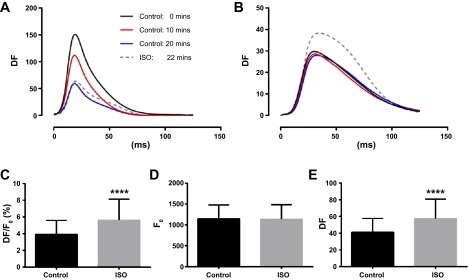

Even so, is not impossible to estimate relative changes in Cai2+ transient amplitude in myocardial tissue. We tested this using simultaneous mapping of rhod 2-AM and the potentiometric dye RH-237 in rat hearts before and after administering the β-adrenergic agonist isoprenaline (1 μM). Hearts were paced at 7 Hz, and fluorescence signals were imaged using a dual optical mapping system. RH-237 photobleaching and washout were identified as slow reductions in optical action potential amplitude (Fig. 2A). However, rhod 2 fluorescence, and the associated Cai2+ transient amplitudes, was stable for >20 min (Fig. 2B). Cai2+ transients recorded immediately before, and 2 min after, administering isoprenaline were compared, revealing a significant increase in Cai2+ transient amplitude after isoprenaline (Fig. 2C). The higher transient amplitude was not the result of drifting background fluorescence (Fig. 2D) but was entirely attributed to a change in fluorescence due to Cai2+ (Fig. 2E). Resolving such amplitude differences by comparing DF/F0 suggests that factors influencing background fluorescence such as distribution of fibrosis, inhomogeneous dye loading, and nonuniformity of illumination could, in certain situations, have little impact on the detection of physiological changes in Cai2+ transient amplitude.

Fig. 2.

Relative changes in rhod 2 fluorescence amplitude after β-adrenergic stimulation in rat hearts. Rhod 2 and RH-237 were imaged simultaneously from the epicardial surface of perfused rat hearts before and after the administration of 1 μM isoprenaline. A: action potential amplitudes fall over time, indicating RH-237 washout. B: intracellular Ca2+ (Cai2+) transient amplitudes are stable for 20 min and increase after administration of isoprenaline (ISO). Average values of DF/F0 (C), F0 (D), and DF (E) 2 min before and 2 min after administration of isoprenaline. ****Significant differences (P < 0.0001).

Potentiometric Probes

Cai2+ transients and optical action potentials can be measured simultaneously when tissue is stained with both a Cai2+ fluorescence probe and a potentiometric probe. Potentiometric probes are lipid-soluble compounds that embed with high affinity within lipid bilayers. When embedded within the sarcolemma, the emission spectrum of a potentiometric probe shifts with changes in transmembrane potential (Vm) to provide a fluorescence signal that represents the action potential. Table 2 lists several potentiometric probes that are commonly used in optical mapping studies of myocardial tissue.

RH-237 and DI-4-ANEPPS are potentiometric probes that are excited by wavelengths in the blue-green band. Fluorescence emission amplitudes (ΔF/F) lie within the range of 5–20% for most potentiometric probes (Table 2). RH-237 and DI-4-ANEPPS exhibit rapid washout and internalization kinetics, requiring frequent reloading of the probe throughout an experiment. Unlike Cai2+ fluorescence probes, potentiometric probes do not gain direct access to organelle membranes. Cellular internalization of the probe occurs, but, once internalized, the probe will no longer respond to changes in membrane potential. Although this increases myocardial background fluorescence and reduces ΔF/F, the assessment of optical action potential kinetics is usually unaffected.

PGH-I and DI-4-ANBDQBS are potentiometric probes with peak excitation within the red band and emission in the near infrared band. Such probes are advantageous for imaging deeper within the myocardium (>4 mm) due to reduced absorption and scattering by endogenous chromophores within the excitation and emission bands of the probes (110). Another advantage is that near-infrared probes enable optical mapping of blood-perfused myocardium (62), avoiding the high absorbance of blood in the shorter blue-green band. PGH-I has far red-shifted excitation and emission spectra and provides large signal amplitudes, but it can be somewhat difficult to load in myocardial tissue. Administering PGH-I in a bolus of slightly acidic perfusate (pH 6.0) provides for optimal tissue loading (81). DI-4-ANBDQBS, the more recently developed styryl dye, can be loaded without an acidic bolus and has similar excitation and emission spectra as PGH-I and low phototoxicity and low washout rate (62).

Optical Mapping Cai2+ Fluorescence from Myocardial Tissue

The same general principles for imaging Cai2+ from myocytes in solution apply to imaging myocytes in situ, where the differences include the optics, detectors, and frame rates used to image large areas of the myocardium (Table 3). One important difference is that Cai2+ transients from myocardial tissue are acquired from a volume of tissue, containing a multitude of myocytes, while Cai2+ transients from suspended myocytes are usually acquired from a single cell, typically using confocal microscopy. Furthermore, myocardial contraction introduces motion artifact in optically mapped Ca2+ signals while signals from cellular studies are less affected by contraction.

Table 3.

Examples of important aspects to consider when imaging Cai2+

| Isolated Cardiomyocytes and Monolayers | Myocardium Cytosolic Ca2+ Imaging | Myocardium SR Ca2+ Imaging | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe compartmentalization | Compartmentalization is condition-dependent. Mitochondria retain rhod 2 (14, 99) and indo 1 (89). Fluo 3 localizes to lysosomes (99). Fluo 5N (84) and mag-fura 2 (33) are retained in the SR after cytosolic washout. | Rhod 2 compartmentalization depends upon experimental conditions. Although rhod 2 may localize to the mitochondria (14), it is often used for myocardium cytosolic Ca2+ imaging (49, 70, 72) and is compatible with other modes of fluorescence imaging (58). | Mag-fluo 4 (45, 104) and fluo 5N (111) are low-affinity dyes that have been used to image SR Ca2+. For SR localization, cytosolic washout at 37°C follows long-term loading at room temperature (45, 111). |

| Probe dissociation constants | Ca2+ transients from isolated cells and monolayers are typically imaged with high-affinity probes such as fluo 4 (95), which may prolong CaD (26, 27). | Fluo 4 is a higher affinity probe than rhod 2, and causes artifacts in the Ca2+ transient, as shown for swine LV at long cycle lengths (43). | Very-low-affinity Ca2+ dyes (Kd >22 μM) are typically used to image SR Ca2+. |

| Measurements derived from Ca2+ transients | Transient amplitudes are typically measured (76). Ratiometry provides Cai2+ concentration and kinetic measurements (22, 90). | Ca2+ kinetics usually measured (39, 52, 70) but not amplitudes. Ratiometry of fura 2 (106, 121), indo 1 (15, 52, 83), or fura red (119) has been used to measure amplitudes. | Nonratiometric imaging provides kinetic measurements and short-term relative assessments of SR Ca2+ release amplitudes (45, 104, 111). |

| Imaging approach | Confocal imaging at rates usually >16 frames/s for monolayers (1, 4). Photomultipliers can provide 1,000 samples/s for isolated cell measurements (92). Photodiode array imaging >500 samples/s (118) and CCD imaging >100 frames/s (1, 11). | Photodiode array systems (20, 52) and CCD/CMOS camera systems (49, 58, 85) are used to image myocardial Ca2+ fluorescence. Frame rates are typically >250 frames/s, but most conventional mapping systems use cameras that image >1,000 frames/s (49). | SR Ca2+ (fluo 5N fluorescence) has been imaged from the epicardium of perfused rabbit hearts at frame rates between 500 and 1,000 frames/s using CMOS cameras (111). |

CaD, intracellular calcium transient duration; LV, left ventricular.

Conventional optical mapping systems image myocardial tissue using charge-coupled device (CCD) or complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) cameras (21, 69). High-power LED light sources, which are cheaper and have a wider range of wavelengths than lasers, provide illumination. Some LEDs have a wide spectral band that may interfere with other fluorescent probes. This is remedied using an excitation filter to shift the spectral peak and narrow the bandwidth. Emitted light is often filtered at a half-width of at least 40 nm at the probe's peak emission wavelength to ensure that adequate light reaches the imaging unit.

Simultaneous imaging of Cai2+ and Vm.

The time of events and intervals between Cai2+ transients and action potentials can be measured by acquiring Cai2+ and Vm signals from the same myocardial sites. Such colocated signals provide valuable insight into excitation contraction coupling and arrhythmia mechanisms. The most desirable and commonly used approach is to couple probes that share the same excitation band and have sufficiently distinct emission bands. Fluorescence signals can then be separated into different detectors using dichroic mirrors and emission filters. With this approach, separate detectors image the fluorescence of each probe to maximize the spatiotemporal resolution of the data. Detectors must be precisely aligned to ensure that Cai2+ and Vm signals are indeed acquired from the same myocardial sites. In early studies, two photodiode arrays were carefully aligned using a six-step manual procedure (19, 20). In contrast to photodiode arrays, CCD and CMOS cameras can be aligned more easily because these detectors provide images. Images of reference grids placed in the field of view are used to align cameras either semimanually (73) or automatically using custom software and postexperiment image processing (37).

Simultaneous imaging of more than one probe also requires careful analysis of spectral content and filtering to minimize signal cross talk. Johnson et al. demonstrated significant cross talk when DI-4-ANEPPS and fluo 3/fluo 4 were used simultaneously (40). Other probe combinations minimize cross talk and maximize signal-to-noise ratios (Table 4). For example, in guinea pig hearts, rhod 2 and RH-237 were shown to be compatible (20) and are commonly used together (17, 49, 50, 60, 70). Systems to simultaneously image indo 1 and DI-4-ANEPPS have been constructed (52, 53), and simultaneous imaging of rhod 2 and DI-4-ANBDQPQ has recently been reported (57).

Table 4.

Selected studies that used Ca2+ fluorescence probes with other exogenous or endogenous fluorescent compounds

| Probes | Description | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|

| Rhod 2 and RH-237 | Cai2+ and Vm | 20, 49, 70 |

| GCaMP3 and RH-237 | Cai2+ and Vm | 85 |

| Fluo 5N and RH-237 | Ca2+SR and Vm | 111 |

| Rhod 2 and di-4-ANBDQPQ | Cai2+ and Vm | 57 |

| Indo 1 and di-4-ANEPPS | Ratio-Cai2+ and Vm | 52, 53 |

| Fura 4F and di-8-ANEPPS | Ratio-Cai2+ and Vm | 36 |

| Fura 2 and FAD+ | Ratio-Cai2+ and endogenous FAD+ | 106 |

Vm, transmembrane potential; FAD+, flavin adenine dinucleotide; ratio-Cai2+, ratiometric Ca2+ measurement.

Acquisition rates.

Frame rates used to image Ca2+ probe fluorescence should provide for adequate reconstruction of the Cai2+ transient. The Nyquist sampling theorem specifies the minimum sample rate to be two times that of the highest frequency content in the signal. SR Ca2+ release is the fastest part of the transient, and the time to peak (TTP) of a Ca2+ transient has been measured to be 20–30 ms for cells paced at 2 Hz (38) and ∼15 ms in rat hearts paced at 5.5 Hz (39). Frame rates as low as 80 frames/s have been used to optically map Cai2+ transients (85). Most conventional optical mapping systems consist of either CCD or CMOS cameras, either of which can acquire full frames at rates of at least 500 frames/s. Rates over 1,000 frames/s are optimal to provide enough samples to accurately measure the rate of SR Ca2+ release and transient amplitudes. The upper limit of useful camera frame rates is ∼4,000, the point where signal-to-noise ratio becomes low. Such high-speed imaging was used to measure changes in the TTP Cai2+ at 4,000 frames/s with a photodiode array (20).

Motion artifact.

Elimination of the motion artifact requires suppression of contraction using electromechanical uncoupling agents (7, 28, 77) or, less frequently, mechanical constraint (112). Blebbistatin is a popular uncoupling agent for optical mapping, especially when imaging Cai2+ because it specifically inhibits the myosin ATPase without altering sarcolemmal ion currents or SR Ca2+ kinetics (28). However, myocyte ATP utilization is severely reduced by electromechanical uncoupling, potentially altering the time course of physiological changes, especially mitochondrial function, during experimental perturbations (47, 105, 114). Motion tracking algorithms (41, 80, 115) and ratiometry (42, 44, 93) are sometimes effective in removing motion artifact from optical action potentials, but there has been less work in the application of motion tracking algorithms to reduce artifact in optically mapped Cai2+ transients. In theory, the same motion tracking algorithms could be used for Cai2+ signals, but publications demonstrating this are presently unknown to us. Cai2+ transients from single sites can be measured in contracting hearts without motion suppression by coupling a fiber optic light guide to the myocardium (29, 64). This provides high temporal resolution Cai2+ signals, but high spatial resolution Cai2+ imaging is not possible.

Analysis of Cai2+ Signals

A handful of physiological measurements are derived from Ca2+ probe fluorescence using a variety of analyses. The most common measurements used to study Cai2+ cycling (Table 5), and methods to compute them, are presented in this section.

Table 5.

Typical measurements derived from Ca2+ fluorescence signals and the general physiological insight they provide

| Parameter | Description | Physiological Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Time-to-peak (TTP) | The time from initiation of Ca2+ departure (t0) to peak fluorescence | RyR Ca2+ release kinetics |

| Rise time | Duration from 10% to 90% of Cai2+ upstroke | RyR Ca2+ release kinetics |

| Maximum departure velocity | The maximum first derivative (dF/dt)max of the Cai2+ upstroke | RyR Ca2+ release kinetics |

| CaD50, CaD80, CaD90 | The duration from t0 to 50, 80, or 90% of cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion | Duration of cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion |

| T50 | The duration from peak to 50% of cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion | Early extrusion phase, fast Ca2+ extrusion, emphasis on SERCA activity (49) |

| Decay time constant (τFall) | The time required for cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion to reach 1-1/e (∼63.2%) of baseline | Late Ca2+ extrusion phase, slow Ca2+ extrusion, emphasis on NCX activity (49) |

| CaD30/CaD80 | Ratio of early Ca2+ extrusion phase to late Ca2+ extrusion phase | Balance of SERCA and NCX activity (49) |

| Vm/Cai2+ phase chirality | The chirality of the phase plot of the normalized Cai2+ signal vs. the normalized Vm signal | Counterclockwise chirality indicates normal Vm/Cai2+ coupling, and clockwise chirality indicates abnormal Vm/Cai2+ coupling (70) |

| CaD-APD | Difference between Cai2+ transient duration and optical action potential duration | Increasing difference between CaD and APD may lead to DAD (49) |

RyR, ryanodine receptor; SERCA, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; NCX, sodium-calcium exchanger; DAD, delayed afterdepolarization.

Preprocessing.

Cai2+ signals, especially those from nonratiometric probes, are averaged, filtered to reduce noise, and normalized before analysis. Spatial smoothing, either by pixel averaging within a defined radius or by convolution with a geometric kernel, is common in Ca2+ optical mapping. Ca2+ signals at each pixel are sometimes ensemble-averaged and/or low pass filtered. Infinite impulse response filtering, as suggested for Vm signals (51), is also appropriate for Ca2+ signals. In fact, spatiotemporal filtering (66) and wavelet analyses (5, 120) that have been optimized for Vm signals could also substantially improve the signal-to-noise ratio of Ca2+ imaging data. Two-dimensional wavelet processing of Ca2+ images, similar to that demonstrated for Vm images (120), shows promise for selective removal of noise while maintaining local image features. This would be advantageous for locating sites of early SR Ca2+ release with precision. In any preprocessing approach, signal distortion should be checked to ensure that any changes in Cai2+ transient morphology, especially the fast upstroke phase, would not alter interpretation of the mapping data.

Cytosolic Cai2+ transient analysis.

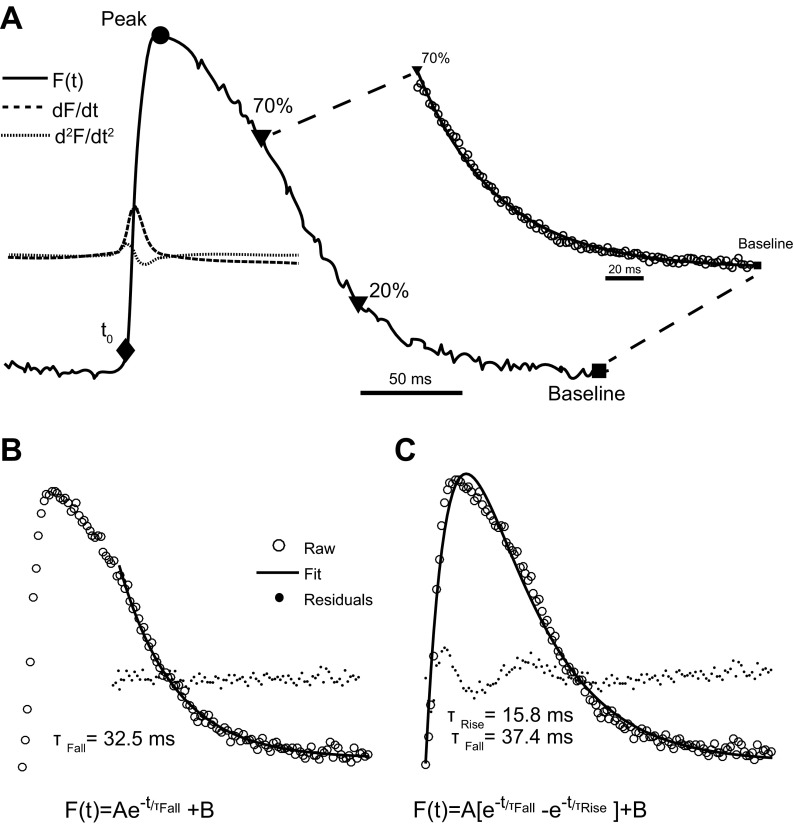

The two main phases of the Cai2+ transient (upstroke and extrusion phases) are usually analyzed separately to quantify the activity of exchangers [Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX)], pumps [SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase], and the SR Ca2+ release channels [ryanodine receptors (RyRs)]. The first step is to identify the onset of the rise in cytosolic Ca2+ (t0), the beginning of the upstroke. The maximum first derivative could be used as a marker for t0 (20), as done for sarcolemmal depolarization (24). An alternative is to detect when fluorescence first exceeds 10% of the amplitude above baseline (20, 53). The maximum of the second derivative has also been used (39), and it provides a value closer to the onset of the upstroke (Fig. 3A). The maximum first derivative of the upstroke is often interpreted as the fastest speed of SR Ca2+ release, an important measure of RyR activity and couplon (9) function. This point usually lies halfway between t0 (if measured using the maximum second derivative) and the transient peak.

Fig. 3.

Cai2+ transient analysis and features used for measuring Cai2+ kinetics. A: Cai2+ transient measured from a perfused rat heart via rhod 2 fluorescence [F(t)]. The first and second derivative of fluorescence (dF/dt and d2F/dt2) are shown for the Cai2+ transient upstroke phase. A monoexponential function was fitted to the late Cai2+ extrusion phase (solid line) from 30% of Cai2+ extrusion to baseline. CaD80 is the time from t0 to 80% of Cai2+ extrusion, corresponding to the marker at 20% above baseline. Time-to-peak (TTP) is the time from t0 to the peak of the Cai2+ transient. B: example of a monoexponential fitted to the late Cai2+ extrusion phase. The residuals of the fit indicate that the main features of the late extrusion phase were fitted with low error. C: example of a biexponential fitted to the same Cai2+ transient shown in B. Residuals of the fit indicate fitting error within the late upstroke phase and the early extrusion phase. τFall, time constant of cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion;τRise, upstroke time constant.

The Cai2+ transient TTP is another important assessment of RyR activity and couplon function, requiring accurate detection of the true transient peak. Signal smoothing and low imaging frame rates introduce errors in measuring the true transient peak. This issue is diminished by measuring the duration of the transient upstroke from 10% above baseline to 90% of the peak, a value known as rise time (53, 70). While the TTP is always longer than rise time, the two values are altered pari passu, as shown in isolated heart studies (63). Signal smoothing and spatial integration may also alter rise time if they significantly alter the upstroke phase of the transient.

CaD is a Ca2+ analog of action potential duration (APD) and is a ubiquitous Ca2+ transient measurement. Even so, there is little consensus on how best to compute CaD, as is also true for APD. CaD is the difference between the time at a specified level of cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion and t0. Levels of 30, 80, and 90% of extrusion have been used for CaD, denoted as CaD30, CaD80, CaD90, respectively. The issue is that the percent of cytosolic Ca2+ removal used to measure CaD in a particular study depends upon the intracellular processes that are affected in an experiment. For example, CaD30 was measured in studies of pyruvate dehydrogenase activation (39) while CaD80 was measured in studies of adrenergic signaling in human heart failure (49). Furthermore, the approach used to identify t0 could alter CaD: the first derivative approach will shorten CaD while the second derivative approach will lengthen it. We suggest using the second derivative approach because the complete Ca2+ upstroke phase will be represented in the measurement of CaD (82).

Optical mapping in guinea pig hearts revealed the effect of activation cycle length on TTP and CaD (20). CaD shortens with cycle length, an outcome linked to APD restitution, which is based on the slow recovery of sarcolemmal L-type Ca2+ channels (78). Reductions in cycle length reduce L-type Ca2+ current, which shortens the plateau phase of the action potential, reducing SR Ca2+ release, resulting in shorter CaD (20). This “CaD restitution” has implications on the TTP. TTP decreases as pacing rate increases, sometimes only within a certain dynamic range. Because L-type Ca2+ channels are still recovering by the next beat during very fast pacing rates (basic cycle length <190 ms in guinea pigs), the TTP can no longer shorten. This effect has only been found in the base, not the apex, of guinea pig hearts (20).

Time constant of cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion.

The time constant of cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion (τFall) is a value that quantifies the rate of fluorescence reduction after the Ca2+ transient upstroke (Fig. 3). This time constant represents the activity of pumps and exchangers that remove Ca2+ from the cytosol. The activity of NCX and SERCA both significantly influence τFall, but one or the other may have a greater influence on the rate of extrusion at different intervals. For example, in human myocardium, the NCX is thought to dominate the late phase of cytosolic Ca2+ extrusion (49). The extrusion phase of the cytosolic Cai2+ transient is often modeled as a single decaying exponential (Eq. 1) (8)

| (1) |

and τFall is measured as shown in Fig. 3B. The transient is often rounded for a short duration after the peak and, depending upon species, may have a shape that is dramatically different from the rest of the extrusion phase. This introduces errors when fitting a single decaying exponential. In this case, a biexponential function could be fitted to the entire Cai2+ transient (Eq. 2). This provides two time constants: one that includes the upstroke (τRise) and one for the extrusion phase (τFall) (74).

| (2) |

τFall computed using Eq. 2, as shown in Fig. 3C, often differs slightly from τFall computed using Eq. 1. An accurate way to fit the late phase of Ca2+ extrusion is to use Eq. 1 and restrict the fit to fluorescence values between 70% of the transient peak and the diastolic baseline (52).

Although τFall is a time constant, it is not independent of transient amplitude, since there is a nonlinear relationship between the two parameters (8). Maximum departure velocity is also dependent upon amplitude, underscoring the importance of maintaining continuity of illumination and camera position, especially when using a nonratiometric probe. Nonratiometric signals were usually normalized to a set range to minimize the effect of amplitude on kinetic measurements such as τFall and departure velocity.

Investigations of Physiology and Disease

Optical mapping of Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes and quantitative analysis of Cai2+ transients have been used to study a spectrum of myocardial physiology and disease conditions. The data are often displayed as a pseudocolor map, providing detailed spatial information for interpreting mechanisms of ectopic activity, alternans, tachycardia, and fibrillation. Recent work using Ca2+ optical mapping to study heart failure, fatal arrhythmias, and metabolic perturbations is briefly discussed below.

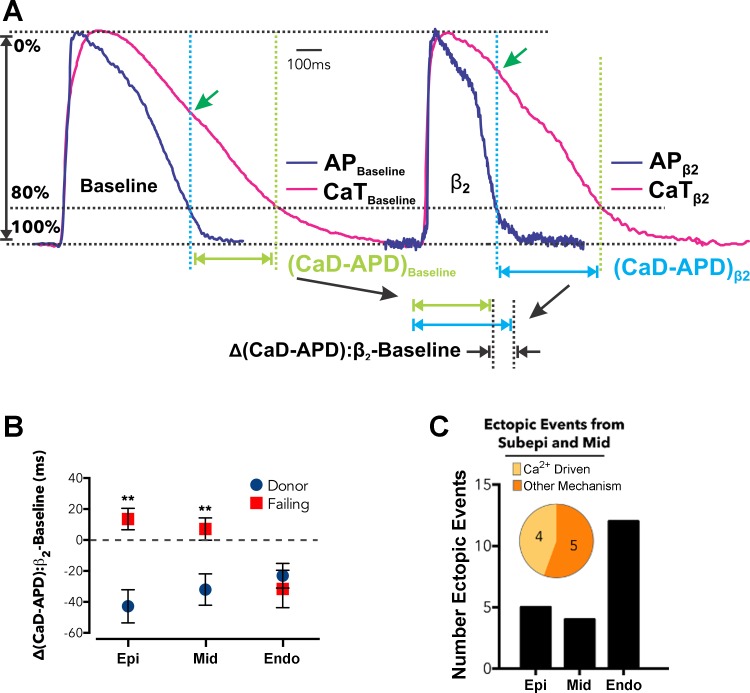

Human heart failure.

Increased cardiac β-adrenergic activity is a common cause of arrhythmia and sudden death in heart failure patients. Recent dual optical mapping studies (RH-237 and rhod 2 AM) in human left ventricle wedge preparations have provided new insights into the response of donor and end-stage failing hearts to β1- and β2-adrenergic stimulation (49). Careful analysis of CaD80 and APD (Fig. 4) revealed that failing hearts were desensitized to β1 stimulation, but β2 stimulation facilitated delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). The DADs were caused by an increase in the time difference between CaD80 and APD [Δ(CaD-APD)], as shown in Fig. 4A. This value indicates a vulnerable window of elevated diastolic Ca2+ that motivates inward NCX current. Maps of Δ(CaD-APD) identified transmural heterogeneities (Fig. 4B), a primary mechanism of PVCs (Fig. 4C). Such Ca2+ optical mapping studies of human myocardium are providing novel insights to improve heart failure therapies, such as the utility of blockers that specifically target β2 receptors.

Fig. 4.

Effect of β2-adrenergic stimulation on Cai2+ transients and optical action potentials that were simultaneously imaged from failing human left ventricular (LV) wedge preparations. A: Cai2+ transients and optical action potentials are shown before (baseline) and after β2 stimulation (β2) of an LV wedge preparation. The tissue was paced at a cycle length of 4 s. Action potential duration (APD) was shorter after β2 stimulation, but CaD80 was unchanged. B: average change in the difference of APD and CaD80 [Δ(CaD-APD)] measured at the epicardium (Epi), midmyocardium (Mid), and endocardium (Endo). C: elevated Δ(CaD-APD) correlated with Ca2+-driven ectopic events. Reproduced with permission from Lang et al. (49).

Cai2+-mediated sarcolemma depolarization.

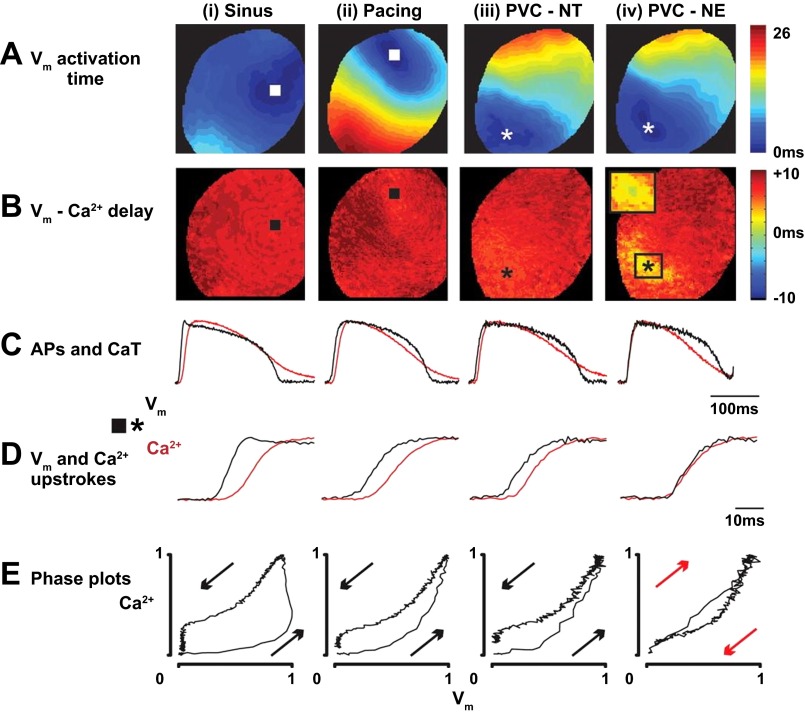

Dual imaging of RH-237 and rhod 2-AM in healthy rabbit hearts has also provided insights into the initiation of spontaneous sarcolemma depolarization after local β-adrenergic receptor activation (Fig. 5) (70). In those studies, subepicardial injections of norepinephrine caused PVCs that exhibited abnormal delays between sarcolemmal depolarization and the Cai2+ transient upstroke (Fig. 5, C and D). The delays were analyzed using phase plots that were constructed by plotting normalized rhod 2 fluorescence vs. normalized RH-237 fluorescence (19). During PVCs, the chirality of the phase plot was reversed (Fig. 5E), indicating depolarization was mediated by local and synchronous release of SR Ca2+ during diastole. The imaging data of these studies provided the first quantitative confirmation in perfused hearts of PVCs caused by SR Ca2+ release during local adrenergic activity.

Fig. 5.

Simultaneous imaging of Cai2+ transients and optical action potentials reveals the origins of premature ventricular contractions in healthy perfused rabbit hearts. Representative data from four activation sequences are shown. The epicardial origin of each beat is indicated as a square or asterisk. i: activation from the sinus node (sinus); ii: activation from a pacing electrode, 300-ms cycle length (pacing); iii: premature ventricular complex during control conditions (PVC-NT); iv: norepinephrine-induced premature ventricular complex (PVC-NE). A: optical action potential (Vm) activation maps. B: maps of the delay from Vm activation to Cai2+ release. C: Vm and Cai2+ transients from the earliest activation sites (square or asterisk). D: closeup of the Vm and Cai2+ transient upstrokes shown in C. E: phase plots of the Vm and Cai2+ transient signals shown in C. Arrows indicate chirality. Reproduced with permission from Myles et al. (70).

Cai2+ dynamics during fibrillation.

Ventricular fibrillation is often preceded by ventricular tachycardia. The transition can be caused by elevated diastolic Cai2+ that leads to Cai2+ transient alternans and then APD alternans that ultimately destabilize the tachycardia (109, 113). Simultaneous imaging studies (RH-237 and rhod 2-AM) of swine right ventricles further demonstrated that, during fibrillation, Cai2+ transients and sarcolemmal potential could become decoupled, without distinct relationships between fluorescence maps and each process having significantly different fundamental rates (73). Later, excised blood-perfused swine hearts were studied using simultaneous imaging to determine the relationship between conduction block and Cai2+ cycling during fibrillation (112). Little difference in the fundamental rates of transmembrane potential and Cai2+ transients was observed, and in most of the area that was imaged 80% of all transient upstrokes occurred during the initial 25% of sarcolemmal depolarization, indicating substantial coupling. However, decoupled Cai2+ transients and sarcolemmal potentials were observed, but exclusively near sites of conduction block, leading to the conclusion that decoupling was a consequence rather than a cause of block (112). Overall, these previous studies demonstrate the unique insights into complex spatiotemporal activity that can be developed using simultaneous imaging of a potentiometric and Ca2+-sensitive probe.

Cai2+ dynamics and metabolism.

In metabolic studies, changes in Cai2+ kinetics that alter contractile function in perfused hearts are measured using Ca2+ fluorescence probes (14, 39, 98). For example, paired optical mapping studies that measured developed pressure, NADH fluorescence, and Cai2+ transients in perfused rat hearts provided mechanistic insights into the inotropic effects of pyruvate and dichloroacetate, two compounds that promote full glucose oxidation in myocytes (39). TTP and CaD30 were reduced by pyruvate and dichloroacetate, indicating increased RyR activity and increased SERCA activity. However, CaD80 remained unchanged due to significant lengthening of τFall, possibly secondary to increased SR Ca2+ load. These studies are an example of increased ventricular contractility without companion measurements of Ca2+ transient amplitude because of the use of a nonratiometric probe (rhod 2) (39). Optical mapping of ratiometric Ca2+ probes would be an especially useful approach in these types of experiments.

Summary

Since the early work of Fabiato in 1985 (25), fluorescence imaging of Ca2+-sensitive fluorescence probes has become an extremely useful approach in optical mapping studies of myocardial tissue and adopted by many cardiovascular research laboratories. Future developments may provide probes with greater quantum yield, enhanced genetically encoded probes that are faster and brighter, and multimode optical mapping systems for imaging ratiometric probes simultaneously with other fluorescent compounds, as well as new developments that are unforeseen. The technology continues to evolve in the ongoing effort to improve therapies that ease the growing worldwide burden of cardiovascular disease.

GRANTS

This work was support by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-095828 (R. Jaimes III, M. W. Kay) and HL-114395 (I. E. Efimov) and ANR Grant 10-IAHU04-LIRYC (R. D. Walton, P. Pasdois, O. Bernus).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.J., R.D.W., P.L.C.P., O.B., and M.W.K. conception and design of research; R.J., R.D.W., P.L.C.P., and O.B. performed experiments; R.J., R.D.W., P.L.C.P., and O.B. analyzed data; R.J., R.D.W., P.L.C.P., O.B., and M.W.K. interpreted results of experiments; R.J., R.D.W., P.L.C.P., and O.B. prepared figures; R.J., I.R.E., and M.W.K. drafted manuscript; R.J., R.D.W., P.L.C.P., O.B., I.R.E., and M.W.K. edited and revised manuscript; R.J., R.D.W., P.L.C.P., O.B., I.R.E., and M.W.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agladze K, Kay MW, Krinsky V, Sarvazyan N. Interaction between spiral and paced waves in cardiac tissue. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H503–H513, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akar FG, O'Rourke B. Mitochondria are sources of metabolic sink and arrhythmias. Pharmacol Ther 131: 287–94, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akerboom J, Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Tian L, Marvin JS, Mutlu S, Calderon NC, Esposti F, Borghuis BG, Sun XR, Gordus A, Orger MB, Portugues R, Engert F, Macklin JJ, Filosa A, Aggarwal A, Kerr RA, Takagi R, Kracun S, Shigetomi E, Khakh BS, Baier H, Lagnado L, Wang SSH, Bargmann CI, Kimmel BE, Jayaraman V, Svoboda K, Kim DS, Schreiter ER, Looger LL. Optimization of a GCaMP calcium indicator for neural activity imaging. J Neurosci 32: 13819–13840, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arutunyan A, Pumir A, Krinsky V, Swift L, Sarvazyan N. Behavior of ectopic surface: effects of beta-adrenergic stimulation and uncoupling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H2531–H2542, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asfour H, Swift LM, Sarvazyan N, Doroslovacki M, Kay MW. Signal decomposition of transmembrane voltage-sensitive dye fluorescence using a multiresolution wavelet analysis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 58: 2083–2093, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahrudin U, Morikawa K, Takeuchi A, Kurata Y, Miake J, Mizuta E, Adachi K, Higaki K, Yamamoto Y, Shirayoshi Y, Yoshida A, Kato M, Yamamoto K, Nanba E, Morisaki H, Morisaki T, Matsuoka S, Ninomiya H, Hisatome I. Impairment of ubiquitin-proteasome system by E334K cMyBPC modifies channel proteins, leading to electrophysiological dysfunction. J Mol Biol 413: 857–878, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker LC, Wolk R, Choi BR, Watkins S, Plan P, Shah A, Salama G. Effects of mechanical uncouplers, diacetyl monoxime, and cytochalasin-D on the electrophysiology of perfused mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1771–H1779, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bers DM, Berlin JR. Kinetics of [Ca]i decline in cardiac myocytes depend on peak [Ca]i. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C271–C277, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bers DM, Perez-Reyes E. Ca channels in cardiac myocytes: structure and function in Ca influx and intracellular Ca release. Cardiovasc Res 42: 339–360, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415: 198–205, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bien H, Yin L, Entcheva E. Calcium instabilities in mammalian cardiomyocyte networks. Biophys J 90: 2628–2640, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blinks JR, Prendergast FG, Allen DG. Photoproteins as biological calcium indicators. Pharmacol Rev 28: 1–93, 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bootman MD, Rietdorf K, Collins T, Walker S, Sanderson M. Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dyes and intracellular Ca2+ imaging. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2013: 83–99, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandes R, Bers DM. Simultaneous measurements of mitochondrial NADH and Ca(2+) during increased work in intact rat heart trabeculae. Biophys J 83: 587–604, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandes R, Figueredo VM, Camacho SA, Baker AJ, Weiner MW. Quantitation of cytosolic [Ca2+] in whole perfused rat hearts using Indo-1 fluorometry. Biophys J 65: 1973–1982, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannell MB, Berlin JR, Lederer WJ. Effect of membrane potential changes on the calcium transient in single rat cardiac muscle cells. Science 238: 1419–1423, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen PS, Ogawa M, Maruyama M, Chua SK, Chang PC, Rubart-von der Lohe M, Chen Z, Ai T, Lin SF. Imaging arrhythmogenic calcium signaling in intact hearts. Pediatr Cardiol 33: 968–974, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499: 295–300, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi BR, Burton F, Salama G. Cytosolic Ca2+ triggers early afterdepolarizations and Torsade de Pointes in rabbit hearts with type 2 long QT syndrome. J Physiol 543: 615–631, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi BR, Salama G. Simultaneous maps of optical action potentials and calcium transients in guinea-pig hearts: mechanisms underlying concordant alternans. J Physiol 529: 171–188, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chong JJH, Yang X, Don CW, Minami E, Liu YW, Weyers JJ, Mahoney WM, Van Biber B, Palpant NJ, Gantz JA, Fugate JA, Muskheli V, Gough GM, Vogel KW, Astley CA, Hotchkiss CE, Baldessari A, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Gill EA, Nelson V, Kiem HP, Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature 510: 273–277, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coutu P, Chartier D, Nattel S. Comparison of Ca2+-handling properties of canine pulmonary vein and left atrial cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2290–H2300, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eerbeek O, Mik EG, Zuurbier CJ, van 't Loo M, Donkersloot C, Ince C. Ratiometric intracellular calcium imaging in the isolated beating rat heart using indo-1 fluorescence. J Appl Physiol 97: 2042–2050, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Efimov IR, Huang DT, Rendt JM, Salama G. Optical mapping of repolarization and refractoriness from intact hearts. Circulation 90: 1469–1480, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabiato A. Rapid ionic modifications during the aequorin-detected calcium transient in a skinned canine cardiac Purkinje cell. J Gen Physiol 85: 189–246, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fast VG, Cheek ER, Pollard AE, Ideker RE. Effects of electrical shocks on Cai2+ and Vm in myocyte cultures. Circ Res 94: 1589–1597, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fast VG. Simultaneous optical imaging of membrane potential and intracellular calcium. J Electrocardiol 38: 107–112, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fedorov VV, Lozinsky IT, Sosunov EA, Anyukhovsky EP, Rosen MR, Balke CW, Efimov IR. Application of blebbistatin as an excitation-contraction uncoupler for electrophysiologic study of rat and rabbit hearts. Hear Rhythm 4: 619–626, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreiro M, Petrosky AD, Escobar AL. Intracellular Ca2+ release underlies the development of phase 2 in mouse ventricular action potentials. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1160–H1172, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fluhler E, Burnham VG, Loew LM. Spectra, membrane binding, and potentiometric responses of new charge shift probes. Biochemistry 24: 5749–5755, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fralix a T, Heineman FW, Balaban RS. Effects of tissue absorbance on NAD(P)H and Indo-1 fluorescence from perfused rabbit hearts. FEBS Lett 262: 287–292, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldhaber JI, Xie LH, Duong T, Motter C, Khuu K, Weiss JN. Action potential duration restitution and alternans in rabbit ventricular myocytes: the key role of intracellular calcium cycling. Circ Res 96: 459–466, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greensmith DJ, Galli GLJ, Trafford AW, Eisner DA. Direct measurements of SR free Ca reveal the mechanism underlying the transient effects of RyR potentiation under physiological conditions. Cardiovasc Res 103: 554–563, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grinvald A, Hildesheim R, Farber IC, Anglister L. Improved fluorescent probes for the measurement of rapid changes in membrane potential. Biophys J 39: 301–308, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herron TJ, Lee P, Jalife J. Optical imaging of voltage and calcium in cardiac cells & tissues. Circ Res 110: 609–623, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holcomb MR, Woods MC, Uzelac I, Wikswo JP, Gilligan JM, Sidorov VY. The potential of dual camera systems for multimodal imaging of cardiac electrophysiology and metabolism. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 234: 1355–1373, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howlett SE. Age-associated changes in excitation-contraction coupling are more prominent in ventricular myocytes from male rats than in myocytes from female rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H659–H670, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaimes R 3rd, Kuzmiak-Glancy S, Brooks DM, Swift LM, Posnack NG, Kay MW. Functional response of the isolated, perfused normoxic heart to pyruvate dehydrogenase activation by dichloroacetate and pyruvate. Pflügers Arch 468: 131–142, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson PL, Smith W, Baynham TC, Knisley SB. Errors caused by combination of Di-4 ANEPPS and Fluo3/4 for simultaneous measurements of transmembrane potentials and intracellular calcium. Ann Biomed Eng 27: 563–571, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khwaounjoo P, Rutherford SL, Svrcek M, LeGrice IJ, Trew ML, Smaill BH. Image-based motion correction for optical mapping of cardiac electrical activity. Ann Biomed Eng 43: 1235–1246, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knisley SB, Justice RK, Kong W, Johnson PL. Ratiometry of transmembrane voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye emission in hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H1421–H1433, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kong W, Fast VG. The role of dye affinity in optical measurements of Cai2+ transients in cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H73–H79, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kong W, Walcott GP, Smith WM, Johnson PL, Knisley SB. Emission ratiometry for simultaneous calcium and action potential measurements with coloaded dyes in rabbit hearts: reduction of motion and drift. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 14: 76–82, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kornyeyev D, Reyes M, Escobar AL. Luminal Ca(2+) content regulates intracellular Ca(2+) release in subepicardial myocytes of intact beating mouse hearts: effect of exogenous buffers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H2138–H2153, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kotlikoff MI. Genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators: using genetics and molecular design to understand complex physiology. J Physiol 578: 55–67, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuzmiak-Glancy S, Jaimes R 3rd, Wengrowski AM, Kay MW. Oxygen demand of perfused heart preparations: how electromechanical function and inadequate oxygenation affect physiology and optical measurements. Exp Physiol 100: 603–616, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA, Vinogradova TM. A coupled SYSTEM of intracellular Ca2+ clocks and surface membrane voltage clocks controls the timekeeping mechanism of the heart's pacemaker. Circ Res 106: 659–673, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lang D, Holzem K, Kang C, Xiao M, Hwang HJ, Ewald GA, Yamada KA, Efimov IR. Arrhythmogenic remodeling of beta2 versus beta1 adrenergic signaling in the human failing heart. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol 8: 409–419, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lang D, Sulkin M, Lou Q, Efimov IR. Optical mapping of action potentials and calcium transients in the mouse heart. J Vis Exp 55: 3275, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laughner JI, Ng FS, Sulkin MS, Arthur RM, Efimov IR. Processing and analysis of cardiac optical mapping data obtained with potentiometric dyes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H753–H765, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laurita KR, Katra R, Wible B, Wan X, Koo MH. Transmural heterogeneity of calcium handling in canine. Circ Res 92: 668–675, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laurita KR, Singal A. Mapping action potentials and calcium transients simultaneously from the intact heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2053–H2060, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee HC, Mohabir R, Smith N, Franz MR, Clusin WT. Effect of ischemia on calcium-dependent fluorescence transients in rabbit hearts containing indo 1. Correlation with monophasic action potentials and contraction. Circulation 78: 1047–1059, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee HC, Smith N, Mohabir R, Clusin WT. Cytosolic calcium transients from the beating mammalian heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 7793–7797, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee P, Bollensdorff C, Quinn TA, Wuskell JP, Loew LM, Kohl P. Single-sensor system for spatially resolved, continuous, and multiparametric optical mapping of cardiac tissue. Heart Rhythm 8: 1482–1491, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee P, Taghavi F, Yan P, Ewart P, Ashley EA, Loew LM, Kohl P, Bollensdorff C, Woods CE. In situ optical mapping of voltage and calcium in the heart. PLoS One 7: e42562, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee P, Yan P, Ewart P, Kohl P, Loew LM, Bollensdorff C. Simultaneous measurement and modulation of multiple physiological parameters in the isolated heart using optical techniques. Pflugers Arch 464: 403–414, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu P, Misurski DA, Gopalakrishnan V. Cysteinyl leukotriene-dependent [Ca2+]i responses to angiotensin II in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1269–H1276, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lou Q, Li W, Efimov IR. Multiparametric optical mapping of the Langendorff-perfused rabbit heart. J Vis Exp 55: 3160, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malli R, Frieden M, Osibow K, Zoratti C, Mayer M, Demaurex N, Graier WF. Sustained Ca2+ transfer across mitochondria is essential for mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering, sore-operated Ca2+ entry, and Ca2+ store refilling. J Biol Chem 278: 44769–44779, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matiukas A, Mitrea BG, Qin M, Pertsov AM, Shvedko AG, Warren MD, Zaitsev AV, Wuskell JP, Wei MD, Watras J, Loew LM. Near-infrared voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes optimized for optical mapping in blood-perfused myocardium. Heart Rhythm 4: 1441–1451, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mattiazzi A, Argenziano M, Aguilar-Sanchez Y, Mazzocchi G, Escobar AL. Ca(2+) Sparks and Ca(2+) waves are the subcellular events underlying Ca(2+) overload during ischemia and reperfusion in perfused intact hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 79: 69–78, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mejía-Alvarez R, Manno C, Villalba-Galea CA, del Valle Fernández L, Costa RR, Fill M, Gharbi T, Escobar AL. Pulsed local-field fluorescence microscopy: a new approach for measuring cellular signals in the beating heart. Pflugers Arch 445: 747–758, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Minta A, Kao JPY, Tsien RY. Fluorescent indicators for cytosolic calcium based on rhodamine and fluorescein chromophores. J Biol Chem 264: 8171–8178, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mironov SF, Vetter FJ, Pertsov AM. Fluorescence imaging of cardiac propagation: Spectral properties and filtering of optical action potentials. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H327–H335, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miyawaki A, Llopis J, Heim R, McCaffery JM, Adams JA, Ikura M, Tsien RY. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature 388: 882–887, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Müller W, Windisch H, Tritthart HA. Fluorescent styryl dyes applied as fast optical probes of cardiac action potential. Eur Biophys J 14: 103–111, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Myles RC, Wang L, Bers DM, Ripplinger CM. Decreased inward rectifying K+ current and increased ryanodine receptor sensitivity synergistically contribute to sustained focal arrhythmia in the intact rabbit heart. J Physiol 593: 1479–1493, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Myles RC, Wang L, Kang C, Bers DM, Ripplinger CM. Local β-adrenergic stimulation overcomes source-sink mismatch to generate focal arrhythmia. Circ Res 110: 1454–1464, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakai J, Ohkura M, Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol 19: 137–141, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Del Nido PJ, Glynn P, Buenaventura P, Salama G, Koretsky AP. Fluorescence measurement of calcium transients in perfused rabbit heart using rhod 2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H728–H741, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Omichi C, Lamp ST, Lin SF, Yang J, Baher A, Zhou S, Attin M, Lee MH, Karagueuzian HS, Kogan B, Qu Z, Garfinkel A, Chen PS, Weiss JN. Intracellular Ca dynamics in ventricular fibrillation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1836–H1844, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palmer BM, Thayer AM, Snyder SM, Moore RL. Shortening and [Ca2+] dynamics of left ventricular myocytes isolated from exercise-trained rats. J Appl Physiol 85: 2159–2168, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Picht E, DeSantiago J, Blatter LA, Bers DM. Cardiac alternans do not rely on diastolic sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content fluctuations. Circ Res 99: 740–748, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Posnack NG, Idrees R, Ding H, Jaimes R 3rd, Stybayeva G, Karabekian Z, Laflamme MA, Sarvazyan N. Exposure to phthalates affects calcium handling and intercellular connectivity of human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 10: e0121927, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qin H, Kay MW, Chattipakorn N, Redden DT, Ideker RE, Rogers JM. Effects of heart isolation, voltage-sensitive dye, and electromechanical uncoupling agents on ventricular fibrillation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1818–H1826, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qu Z, Xie Y, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN. T-wave alternans and arrhythmogenesis in cardiac diseases. Front Physiol 1: 154, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ridgway EB, Ashley CC. Calcium transients in single muscle fibers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 29: 229–234, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rohde GK, Dawant BM, Lin SF. Correction of motion artifact in cardiac optical mapping using image registration. Biomed Eng IEEE Trans 52: 338–341, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Salama G, Choi BR, Azour G, Lavasani M, Tumbev V, Salzberg BM, Patrick MJ, Ernst LA, Waggoner AS. Properties of new, long-wavelength, voltage-sensitive dyes in the heart. J Membr Biol 208: 125–140, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Salama G, Hwang SM. Simultaneous optical mapping of intracellular free calcium and action potentials from langendorff perfused hearts. Curr Protoc Cytom Chapter 12: Unit 12 17, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schreur JH, Figueredo VM, Miyamae M, Shames DM, Baker AJ, Camacho SA. Cytosolic and mitochondrial [Ca2+] in whole hearts using indo-1 acetoxymethyl ester: effects of high extracellular Ca2+. Biophys J 70: 2571–2580, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shannon TR, Guo T, Bers DM. Ca2+ scraps local depletions of free [Ca2+] in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum during contractions leave substantial Ca2+ reserve. Circ Res 93: 40–45, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shiba Y, Fernandes S, Zhu WZ, Filice D, Muskheli V, Kim J, Palpant NJ, Gantz J, Moyes KW, Reinecke H, Van Biber B, Dardas T, Mignone JL, Izawa A, Hanna R, Viswanathan M, Gold JD, Kotlikoff MI, Sarvazyan N, Kay MW, Murry CE, Laflamme MA. Human ES-cell-derived cardiomyocytes electrically couple and suppress arrhythmias in injured hearts. Nature 489: 322–325, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimomura O, Johnson FH, Saiga Y. Microdetermination of calcium by aequorin luminescence. Science 140: 1339–1340, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shkryl VM, Maxwell JT, Domeier TL, Blatter LA. Refractoriness of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release determines Ca2+ alternans in atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H2310–H2320, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sollott SJ, Ziman BD, Lakatta EG. Novel technique to load indo-1 free acid into single adult cardiac myocytes to assess cytosolic Ca2+. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H1941–H1949, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Spurgeon HA, Stern MD, Baartz G, Raffaeli S, Hansford RG, Talo A, Lakatta EG, Capogrossi MC. Simultaneous measurement of Ca2+, contraction, and potential in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 258: H574–H586, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Srikanth S, Gwack Y. Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ concentration in single cells using ratiometric calcium dyes. Methods Mol Biol 963: 3–14, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sulkin MS, Boukens BJ, Tetlow M, Gutbrod SR, Ng FS, Efimov IR. Mitochondrial depolarization and electrophysiological changes during ischemia in the rabbit and human heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1178–H1186, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sun H, Chartier D, Leblanc N, Nattel S. Intracellular calcium changes and tachycardia-induced contractile dysfunction in canine atrial myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 49: 751–761, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tai DCS, Caldwell BJ, LeGrice IJ, Hooks DA, Pullan AJ, Smaill BH. Correction of motion artifact in transmembrane voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye emission in hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H985–H993, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takahashi A, Camacho P, Lechleiter JD, Herman B. Measurement of intracellular calcium. Physiol Rev 79: 1089–1125, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Takeuchi A, Kim B, Matsuoka S. The mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, NCLX, regulates automaticity of HL-1 cardiomyocytes. Sci Rep 3: 2766, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tallini YN, Ohkura M, Choi BR, Ji G, Imoto K, Doran R, Lee J, Plan P, Wilson J, Xin HB, Sanbe A, Gulick J, Mathai J, Robbins J, Salama G, Nakai J, Kotlikoff MI. Imaging cellular signals in the heart in vivo: Cardiac expression of the high-signal Ca2+ indicator GCaMP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 4753–4758, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, Bargmann CI, Jayaraman V, Svoboda K, Looger LL. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods 6: 875–881, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]