Abstract

Objectives

To identify risk and risk factors for developing a subsequent febrile seizure (FS) in children with a first febrile status epilepticus (FSE) compared to a first simple febrile seizure (SFS). To identify home use of rescue medications for subsequent FS.

Methods

Cases included a first FS that was FSE drawn from FEBSTAT and Columbia cohorts. Controls were a first SFS. Cases and controls were classified according to established FEBSTAT protocols. Cumulative risk for subsequent FS over a five year period was compared in FSE versus SFS and Cox proportional hazards regression was conducted. Separate analysis examined subsequent FS within FSE. The use of rescue medications at home was assessed for subsequent FS.

Results

Risk for a subsequent FSE was significantly increased in FSE versus SFS. Any MRI abnormality increased the risk 3.4-fold (p<0.05), adjusting for age at first FS and FSE and in analyses restricted to children whose first FS was FSE (any MRI abnormality HR=2.9, p<0.05). The risk for a second FS of any type or of subsequent FS lasting >10 minutes over the five-year follow-up did not differ in FSE versus SFS.

Rectal diazepam was administered at home to 5 of 21 children (23.8%) with subsequent FS lasting ≥10 minutes.

Significance

Compared to controls, FSE was associated with an increased risk for subsequent FSE, suggesting the propensity of children with an initial prolonged seizure to experience a prolonged recurrence. Any baseline MRI abnormality increased the recurrence risk when FSE was compared to SFS and when FSE was studied alone. A minority of children with a subsequent FS lasting 10 minutes or longer were treated with rectal diazepam at home, despite receiving prescriptions after the first FSE. This indicates the need to further improve the education of clinicians and parents in order to prevent subsequent FSE.

Keywords: Febrile Seizure recurrence, Status Epilepticus, Simple febrile seizure

INTRODUCTION

Population-based and birth cohort studies have examined the risk for subsequent febrile seizures (FS) and find that the risk of a first recurrence ranges from 23%–42% 1; 2 with more than 90% of recurrence occurring during the first two years. In pooled studies, the risk for a first recurrence during a three year period ranges from 28% to 32% in population-based studies and 33% to 43% in clinic-based studies3.

Among children with a first FSE compared to a first simple febrile seizure (SFS), risk factors for FS recurrence are less well described. One study found that children with a first simple FS were less likely to have a subsequent FS lasting ≥10 minutes than children with a first complex FS lasting ≥10 minutes4. This suggests that long duration FS is associated with long duration recurrences. We address this in the FEBSTAT study, considering the 5-year risk for any subsequent FS, subsequent FSE and subsequent FS lasting ≥10 minutes, compared to controls with simple FS.

METHODS

We combined the FEBSTAT cohort of children with FSE, the existing Duke cohort with FSE, and the Columbia University Febrile Seizure Study cohort children with a first FSE to form the case group.5–7 FSE was defined as a seizure lasting 30 minutes or more. Subjects with FSE were recruited from Emergency Departments of five sites for FEBSTAT. Subjects with a first FS in the Columbia Study were recruited from the Emergency Department of the New York Presbyterian Hospital; first simple FS were included. Excluded were children with a first complex FS that was not FSE (defined as duration more than 10 minutes, focality and/or repeated FS in the same illness). Protocols were similar across studies, identical questionnaires were used, and MRI and phenomenology consensus were performed by the same individuals for all cohorts 6.

Cases were children with FSE that was their first ever FS. Controls were children with a first simple FS (FS lasting less than 10 minutes, non-focal and not repeated in the same febrile illness) from the Columbia Study cohort. FS was defined as a seizure provoked by a temperature greater than 38.4°C (101.0 °F) without a prior afebrile seizures or acute CNS infection or insult.8 FSE was defined as a seizure lasting 30 minutes or longer without fully regaining consciousness.9 While the definition of status is evolving, this remains the appropriate definition for studies of consequences of status 10. Moderately prolonged FS were considered to last ≥10 minutes.

Consensus for FS type, MRI and EEG

Description of the FS was obtained through interview with family members and from abstracted medical record data. This information was used to assign FS type and duration by consensus among three pediatric epileptologists (SShinnar, JMP, DRN) who were blind to the child’s MRI results. For the last year of study prior to this analysis, Dr Seinfeld scored together with Dr Pellock as the third rater. Cases of subsequent FS were also analyzed by the phenomenology core though the amount of data available was often less detailed except in cases of prolonged events in which detailed interview was performed 11.

MRI was performed within 72 hours after the first FS or very shortly thereafter for cases and controls. Two neuroradiologists (JB, SC) read the MRIs blinded to all clinical details except age. Pre-existing structural abnormalities on MRI were examined regardless of location.12 Abnormalities included those classified as suspect and definite.

EEG data were available for the FEBSTAT subjects only. Baseline EEGs were performed within 72 hours of the FSE and were read centrally by two electroencephalographers (DRN and SLM) who were blinded to the clinical and MRI data 13.

Risk factors

Using questions from the baseline structured interview, we considered: sociodemographics, baseline fever, first degree family history of febrile seizures and of epilepsy, and MRI abnormalities.. First degree relatives included siblings and parents. Age at first FS was categorized as <18 months or ≥18months. Temperature in the emergency department was categorized as <104.0°F or ≥104 °F. Development was categorized as abnormal versus normal. MRI abnormalities were categorized as abnormal hippocampus versus normal hippocampus and as MRI abnormality versus normal, using the neuroradiologists’ consensus readings. FSE was classified as focal or not. EEG was classified as normal or abnormal for the FEBSTAT subjects 13, HHV6/HHV7 was identified at baseline for FEBSTAT subjects and classified as present or absent 14. EEG and HHV6/7 status were unavailable for the Columbia and the Duke cohort. Simple FS were not focal, multiple or prolonged.

Outcomes

We considered subsequent FS as: a second FS of any type, a subsequent FSE, and a subsequent FS lasting 10 minutes or longer (prolonged FS). 15 This was done to determine if FSE as the initial FS predicts a higher risk of a subsequent prolonged FS that is not FSE.

Rescue medications

The use of rescue medications for subsequent FS was assessed.

Institutional Review Board (IRB)

The IRB at all sites approved procedures and parents signed informed consent.

Statistical analysis

We used Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests and t-tests for bivariate analysis. Kaplan Meier curves were generated for each of the three outcomes, comparing FSE to simple FS, testing the difference in curves using the Wilcoxon test. Subjects’ data were censored if epilepsy occurred before a recurrent FS and/or if loss to follow-up occurred.

Cox proportional hazards regression, comparing FSE to SFS, considered each potential risk factor in univariate analyses. Two multivariable analyses were conducted: (1) only FSE and age at the first FS; and (2) potential risk factors, adjusting for FSE versus simple FS and age at first FS.

An additional Cox proportional hazards regression restricted to FSE considered the same risk factors in univariate models for each of the three types of subsequent FS.

RESULTS

Among the 294 children with first FS that was either simple FS or FSE, 193 had FSE and 101 had simple FS (Table 1). Age at first FS was less than 18 months for 63.2% of FSE and 41.6% of simple FS. Baseline MRI readings were available for 95.3% of FSE and 93.7% of simple FS. Peak temperature equal to or higher than 104 accounted for 31.3% of FSE and 51.0% of simple FS. For this analysis, follow-up data was available for 4.0 years on the Columbia cohort and for the first 5 years on the FEBSTAT and Duke cohorts.

Table 1.

Risk for a subsequent FSE in children with a first FS that was FSE versus a first FS that was simple FS

| Factor | Risk factor frequency by cohort | Hazard Ratio for first subsequent FSE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| FSE N (%) |

Simple FS N (%) |

Univariate HR (95 CI) |

Multivariate1 HR (95 CI) |

Multivariate2 HR (95 CI) |

|

|

| |||||

| Simple FS | NA | 101 (100.0 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| FSE | 193 (100.0) | NA | 4.5 (1.03, 19.6) | 3.5 (0.8, 15.5) | 3.2 (0.7,14.5) |

|

| |||||

| < 18 months at first FS1 | 122 (63.2) | 42 (41.6) | 1.0 (Ref) | - | - |

| ≥ 18 months at first FS | 71 (36.8) | 59 (58.4) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.7) | - | - |

|

| |||||

| Non-focal FS2 | 51 (26.4) | 101 (100) | 1.0 (Ref) | - | - |

| Focal FS | 142 (73.6) | NA | 1.8 (0.7, 4.6) | - | - |

|

| |||||

| Normal hippocampus3 | 152 (83.5) | 93 (97.9) | 1.0 (Ref) | - | - |

| Abnormal hippocampus | 30 (16.5) | 2 (2.1) | 3.4 (1.2, 9.7) | - | - |

|

| |||||

| Normal MRI 4 | 140 (76.1) | 86 (90.5) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | - |

| MRI abnormality | 44 (23.9) | 9 (9.5) | 4.1 (1.6, 10.4) | 3.4 (1.3, 8.7) | - |

|

| |||||

| Normal development 5 | 176 (91.2) | 99 (98.0) | 1.0 (Ref) | - | - |

| Abnormal development | 17 (8.8) | 2 (2.0) | 3.4 (0.98, 11.7) | - | - |

|

| |||||

| Peak temperature < 104 °F 6 | 132 (68.8) | 4 (49.0) | 1.0 (Ref) | - | - |

| Peak temperature < 104 °F 6 | 60 (31.3) | 51 (51.0) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.5) | - | - |

|

| |||||

| No Family history of FS 7 | 107 (67.3) | 79 (79.8) | 1.0 (Ref) | - | - |

| Positive family history of FS | 52 (32.7) | 20 (20.2) | 1.6 (0.3, 7.8) | - | - |

|

| |||||

| No Family history of Epilepsy 8 | 137 (86.2) | 91 (91.9) | 1.0 (Ref) | - | - |

| Positive family history of Epilepsy9 | 22 (13.8) | 8 (8.1) | 0.5 (0.1,4.1) | - | - |

|

| |||||

| No Acute T2 Signal10 | 164 (90.11) | 92(100) | 1.0 (Ref) | - | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Acute T2 Signal | 18 (9.89) | NA | 5.1 (1.7,15.8) | - | 3.8 (1.2,12.1) |

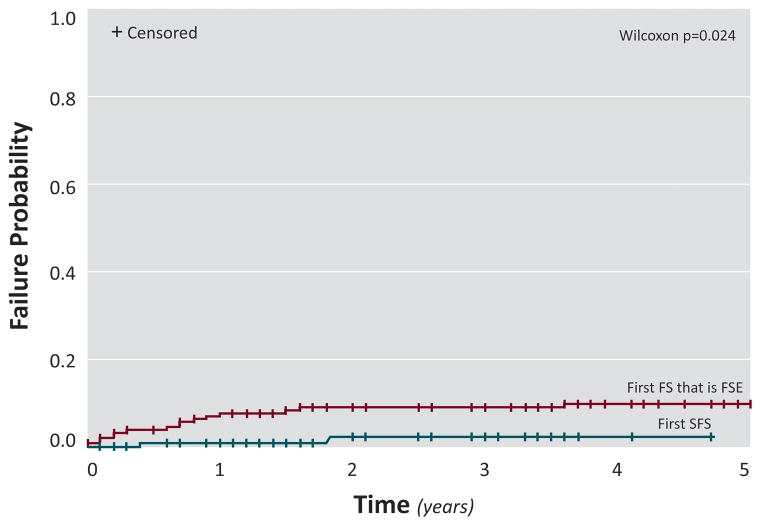

Risk for subsequent febrile seizures in FSE versus simple FS over a five year period (Figure 1 and Supplemental figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1.

Risk for a subsequent FSE after a first FS that was FSE compared to a first SFS

The risk for recurrence of a second FS of any type was 42.9% in FSE versus 28.9% in SFS (Wilcoxon p=0.094; Supplemental Figure 1); 74 (73.3%) of subjects with SFS and 125 (64.8%) of FSE were censored. The risk for a subsequent FSE was 9.9% in FSE versus 2.3 % in SFS (Wilcoxon p=0.024; Figure 1) 99 (98.0%) of subjects with SFS and 177 (91.7%) of FSE were censored. The risk for a FS lasting more than 10 minutes was 10.7% in FSE versus 6.4% in SFS (Wilcoxon p=0.34; Supplemental Figure 2); 95 (94.1%) of subjects with SFS and 176 (91.2%) of FSE were censored.

Cox Proportional Hazard Regression

FSE compared to SFS

Comparing the risk for subsequent FS in those whose initial FS that was FSE versus those with an initial FS that was SFS, no risk factors were associated with a second FS of any type or a subsequent FS lasting >10 minutes (data not shown).

MRI abnormalities were associated with a 3.4-fold increased risk for a subsequent FSE (95% CI: 1.3–8.7) after adjustment for FS type (Table 1). Similarly, acute T2 signal at baseline was associated with a 3.8-fold increased risk of subsequent FSE (95%CI: 1.2–12.1) adjusting for FS.

Subsequent FS in the FSE (Supplemental Table 1)

No factors were significantly associated with a second FS of any type or with a second FS lasting ≥10 minutes. In univariate analyses, MRI abnormality and increased T2 signal were associated with a statistically significant increased risk for a subsequent FSE (MRI abnormality HR=2.9; 95% CI 1.1–7.9; increased T2 signal HR=3.8: 95% CI 1.2–11.9).

Use of rescue medications

Thirteen children with an initial FS that was FSE had a second FS that was FSE, and 11 (84.6%) received rescue medications: 2 (18.2%) at home and 9 (81.8%) in the ambulance (Supplemental Figure 3a). Seventy children had a second FS that was less than 30 minutes. Rescue medications were given at home to 2 out of 18 children (11.1%) with an FS lasting < 5 minutes, 9 out of 26 (34.6%) with an FS lasting 5 to 10 minutes, 3 out of 8 children (37.5%) with an FS lasting 10 minutes to 30 minutes, and 1 out of 5 (20%) with an FS of unknown length. (Supplemental Figure 3a)

There were 145 subsequent FS across children with a first FS that was FSE. Among them, there were 16 subsequent FSE. Rescue medications were given in 12 (75%) children: three of the 12 children (25%) at home, and 9 of the 12 (75%) in the ambulance. (Supplemental Figure 3b)

DISCUSSION

Ours is the largest study of risk for recurrent FS in children with FSE compared to children with SFS. We found that the cumulative risk for recurrent FSE was significantly increased in FSE versus SFS, but not for FS lasting less than 30 minutes. The modestly increased risk of recurrence of a second FS of any type in the FSE group was explained by younger age at the first FS that was FSE, which occurs at a younger age than other FS types 16. Additionally, any MRI abnormality was associated with an increased risk for recurrent FSE in children with a first FS that was FSE compared to SFS controls and persisted after adjustment for FSE. No other factors were related to FS recurrence. Any MRI abnormality and separately increased T2 signal increased the risk for subsequent FSE when analysis was restricted to the FSE group. No other risk factors for recurrence emerged in the analysis restricted to FSE.

Others have shown that the risk for subsequent prolonged FS is increased in FSE 1; 4, suggesting that lower seizure threshold indexed by younger age at onset first FS, lower temperature at the first FSE and impaired ability to spontaneously stop a prolonged seizure may be inherent features in these children 16. Additionally, the risk for subsequent afebrile SE 17–19 echoes the tendency to experience prolonged seizure recurrences. Thus, our finding that children with a first FSE are more likely to experience a subsequent FSE than SFS controls is consistent with the prior literature.

Any MRI abnormality at baseline was associated with an increased risk for subsequent FSE in FSE versus SFS controls and separately in FSE. Consistent with the Columbia first febrile seizure study, MRI abnormalities were 4.3-fold more common in children with focal and prolonged FS 5 compared to children with SFS (95% CI: 12.–15.0) and with baseline data in the FEBSTAT study 12 in whichchildren with FSE were more likely to have any MRI abnormality versus those with SFS. Increased T2 signal accounted for an increased risk for subsequent FSE in those with a first FS that was FSE.

While EEG abnormalities, primarily temporal slowing or attenuation, were frequent in the FSE group and were associated with presence of hippocampal T2 signal 13, they were not associated with a differential risk of the subsequent FS types studied. Presence of focal slowing or attenuation on an EEG following FSE has been associated with subsequent development of epilepsy but has not been associated with an increased risk of recurrent FS, and these results are consistent with the available literature 20; 21.

HHV6/7 viruses are common causes of fever in young children and can be associated with FS; 22; 23 however, we found no association between HHV6/7 and subsequent FS.

Several risk factors found in studies of children with a first FS, in which FSE is a very small percentage, were not associated with FS recurrence in our study. These include focal FS, abnormal development, peak temperature at the first FS, positive family history or FS and positive family history of epilepsy. In prior studies of FS recurrence, the contribution of these risk factors differed from our study. The likely reason for this difference in FEBSTAT is that the ratio of first FSE to SFS was 1.9:1, and was not reflective of first FS studies in which the ratio of FSE to SFS is 0.05:1 to 0.09:1 6; 24. This is the first study examining risk factors for recurrent FS in children with FSE, yielding only MRI abnormality as a risk factor for recurrence.

As discussed above, the children whose initial FS was FSE had a higher risk of subsequent FSE. However, our data may actually underestimate this increased risk. Children with initial FSE were frequently prescribed rectal diazepam gel as abortive therapy to prevent the risk for another prolonged FS 25; 26. This was not the case for children with an initial SFS where, in line with the Academy of Pediatrics guidelines 27 no rescue medications were prescribed. Parents of children whose initial FS was FSE used abortive therapy even for a brief FS; thus, resulting in shorter seizure duration 28. It is likely that, at least in some cases, subsequent FS did not evolve to FSE due to utilization of abortive therapy, thereby potentially underestimating the untreated risk for subsequent FSE after FSE, and further indicating the need to educate clinicians and parents to administer rescue drugs to prevent prolonged seizures.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Compared to simple febrile seizures (SFS), there is a propensity for children with febrile status epilepticus (FSE) to experience subsequent prolonged seizures.

Any MRI abnormality was a risk factor for subsequent FSE when compared to SFS and when restricted to FSE; this may be due, in part, to hippocampal abnormalities.

A minority of children with a first FS that was FSE were treated with abortive therapy, indicating the need for further education of parents.

Some children with FSE may not have evolved to a subsequent FSE due to utilization of abortive therapy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NS 43209 from NINDS (PI: S. Shinnar) and HD 36867 from NICHD (PI: DC Hesdorffer). FEBSTAT Study Team: Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY: Shlomo Shinnar MD PhD, Jacqueline Bello MD, Evelyn Berman MD, William Gomes MD PhD, James Hannigan RT, Sharyn Katz R-EEGT, FASET, Ann Mancini MA, David Masur PhD, Solomon L. Moshé MD, Ruth Shinnar RN MSN, Yoshimi Sogawa MD, Erica Weiss PhD. Columbia University, New York, NY: Dale Hesdorffer PhD, Stephen Chan MD, Binyi Liu MS. Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Darrell Lewis MD, Melanie Bonner PhD, Karen Cornett BS, MT, William Gallentine DO, James MacFall PhD, James Provenzale MD, Allen Song PhD, James Voyvodic PhD, Yuan Xu BS. Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA: L. Matthew Frank MD, Joanne Andy RT, Terrie Conklin RN, Susan Grasso MD, Connie S. Powers R-EEG T, David Kushner MD, Susan Landers RT, Virginia Van de Water PhD. International Epilepsy Consortium at Department of Biostatistics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA: Shumei Sun PhD, John Pellock MD, Brian J Bush MSMIT, Lori L Davis BA, Xiaoyan Deng MS, Christiane Rogers, Cynthia Shier Sabo MS. Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital, Chicago, IL: Douglas Nordli MD, John Curran MD, Leon G Epstein MD, Andrew Kim MD, Diana Miazga, Julie Rinaldi PhD. Mount Sinai Medical Center: Emilia Bagiella PhD. Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA: John Pellock MD, Tanya Brazemore R-EEGT, James Culbert PhD, Kathryn O’Hara RN, Syndi Seinfeld DO, Jean Snow RT-R.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript. We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

References

- 1.Annegers JF, Blakley SA, Hauser WA, et al. Recurrence of febrile convulsions in a population-based cohort. Epilepsy Res. 1990;5:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(90)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forsgren L, Heijbel J, Nystrom L, et al. A follow-up of an incident case-referent study of febrile convulsions seven years after the onset. Seizure. 1997;6:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(97)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Offringa M, Bossuyt PM, Lubsen J, et al. Risk factors for seizure recurrence in children with febrile seizures: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from five studies. J Pediatr. 1994;124:574–584. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg AT, Shinnar S. Complex febrile seizures. Epilepsia. 1996;37:126–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hesdorffer DC, Chan S, Tian H, et al. Are MRI-detected brain abnormalities associated with febrile seizure type? Epilepsia. 2008;49:765–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hesdorffer DC, Shinnar S, Lewis DV, et al. Design and phenomenology of the FEBSTAT study. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1471–1480. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis DV, Barboriak DP, MacFall JR, et al. Do prolonged febrile seizures produce medial temporal sclerosis? Hypotheses, MRI evidence and unanswered questions. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:263–278. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)35025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NIH. Book Consensus development conference summary. NIH; Bethesda: 1980. Consensus development conference summary. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Commission on Epidemiology and Prognosis of the International League Against Epilepsy. Guidelines for epidemiological studies on epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1993;34:592–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus - Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56:1515–1523. doi: 10.1111/epi.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinnar S, Hesdorffer DC, Nordli DR, Jr, et al. Phenomenology of prolonged febrile seizures: results of the FEBSTAT study. Neurology. 2008;71:170–176. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310774.01185.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shinnar S, Bello JA, Chan S, et al. MR abnormalities following febrile status epilepticus in children: The FEBSTAT Study. Neurology. 2012;79:871–877. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318266fcc5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordli DR, Jr, Moshe SL, Shinnar S, et al. Acute EEG findings in children with febrile status epilepticus: results of the FEBSTAT study. Neurology. 2012;79:2180–2186. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182759766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein L, Shinnar S, Hesdorffer DC, et al. Human Herpesvirus 6 and 7 in Febrile Status Epilepticus: The FEBSTAT study. Epilepsia. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesdorffer DC, Benn EK, Bagiella E, et al. Distribution of febrile seizure duration and associations with development. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:93–100. doi: 10.1002/ana.22368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hesdorffer DC, Shinnar S, Lewis DV, et al. Risk factors for febrile status epilepticus: a case-control study. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1147–1151. e1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Cascino GD, et al. Recurrence of afebrile status epilepticus in a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Neurology. 2007;69:73–78. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265056.31752.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsetsou S, Novy J, Rossetti AO. Recurrence of status epilepticus: prognostic role and outcome predictors. Epilepsia. 2015;56:473–478. doi: 10.1111/epi.12903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinnar S, Berg AT, Moshe SL, et al. The risk of seizure recurrence after a first unprovoked afebrile seizure in childhood: an extended follow-up. Pediatrics. 1996;98:216–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordli DR, Moshe SL, Shinnar S. The role of EEG in febrile status epilepticus (FSE) Brain Dev. 2010;32:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sofijanov N, Emoto S, Kuturec M, et al. Febrile seizures: clinical characteristics and initial EEG. Epilepsia. 1992;33:52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theodore WH, Epstein L, Gaillard WD, et al. Human herpes virus 6B: a possible role in epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2008;49:1828–1837. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall CB, Long CE, Schnabel KC, et al. Human herpesvirus-6 infection in children. A prospective study of complications and reactivation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:432–438. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408183310703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berg AT, Shinnar S, Darefsky AS, et al. Predictors of recurrent febrile seizures. A prospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:371–378. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170410045006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinnar S. Who is at risk for prolonged seizures? J Child Neurol. 2007;22:14S–20S. doi: 10.1177/0883073807303065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinnar S, Berg AT, Moshe SL, et al. How long do new-onset seizures in children last? Ann Neurol. 2001;49:659–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steering Committee on Quality I Management SoFSAAoP. Febrile seizures: clinical practice guideline for the long-term management of the child with simple febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1281–1286. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seinfeld S, Shinnar S, Sun S, et al. Emergency management of febrile status epilepticus: results of the FEBSTAT study. Epilepsia. 2014;55:388–395. doi: 10.1111/epi.12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.