Abstract

A unique mass spectrometry (MS) method has been developed to determine the negatively charged species in live single cells using the positive ionization mode. The method utilizes dicationic ion-pairing compounds through the miniaturized multifunctional device, the single-probe, for reactive MS analysis of live single cells under ambient conditions. In this study, two dicationic reagents, 1,5-pentanediyl-bis(1-butylpyrrolidinium) difluoride (C5(bpyr)2F2) and 1, 3-propanediyl-bis-(tripropylphosphonium) difluoride (C3(triprp)2F2), were added in the solvent and introduced into single cells to extract cellular contents for real-time MS analysis. The negatively charged (1− charged) cell metabolites, which form stable ion-pairs (1+ charged) with dicationic compounds (2+ charged), were detected in positive ionization mode with a greatly improved sensitivity. We have tentatively assigned 192 and 70 negatively charged common metabolites as adducts with (C5(bpyr)2F2) and (C3(triprp)2F2), respectively, in three separate SCMS experiments in the positive ion mode. The total number of tentatively assigned metabolites is 285 for C5(bpyr)2F2 and 143 for C3(triprp)2F2. In addition, the selectivity of dicationic compounds in the complex formation allows for the discrimination of overlapped ion peaks with low abundances. Tandem (MS/MS) analyses at the single cell level were conducted for selected adduct ions for molecular identification. The utilization of the dicationic compounds in the single-probe MS technique provides an effective approach to the detection of a broad range of metabolites at the single cell level.

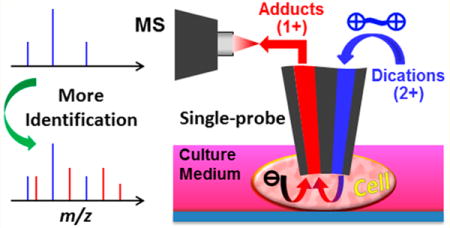

Graphical abstract

Single cell analysis (SCA) has become an important and increasingly active area in biological studies. Compared with the traditional methods that are based on the population averaged studies, SCA can provide a more nuanced analysis of the underlying biological mechanics of the system being studied by illustrating biological differences at the level of individual cells.1–4 SCA encompasses a variety of analytical techniques, including single cell transcriptomics,5–8 single cell genomics,9 single cell fluorescent tagging,10 Raman spectroscopy imaging,11 and others.

Single cell mass spectrometry (SCMS) is a nascent field that has gained a great deal of interest in mass spectrometry (MS) research.12–14 MS is a versatile technique to simultaneously analyze a large number of molecules in a short period of time. Traditional MS approaches to cell analysis were restricted to a population of cells (such as cell lysate), where an averaged result is obtained. Recent advancements in high mass resolution MS has allowed for the confident assignment of large numbers of molecules,15 and improved sensitivity enables MS to be applied at the single cell level, mostly in the field of metabolomics,14 and potentially single cell peptidomics16 and proteomics.17 Current SCMS techniques can be broadly categorized into nonambient and ambient techniques, based on their sampling environment. Common nonambient techniques include matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) MS18,19 and time-of-flight secondary ion MS (TOF-SIMS)20,21 approaches, which are capable of high spatial resolution22 for cellular and subcellular resolution analysis of the cell organelles.23–25 However, nonambient techniques require obligatory sample pretreatment and a vacuum sampling environment, and they are not suitable for live cell analysis.

Ambient SCMS techniques allow for analysis of live single cells in an ambient environment with little to no sample preparation. Techniques include laser assisted electrospray ionization (LAESI) MS,26,27 single cell capillary electrophoresis (CE) ESI MS,28,29 probe ESI MS,30 and live single-cell video-MS (live MS).31–33 Among these methods, the live MS technique is based on the direct extraction of cellular compounds using a sharp nano-ESI emitter followed by offline MS analysis.32 However, due to the separate steps needed for sampling and analysis in live MS experiment, metabolites that are sensitive to the cell status are possibly changed during sample transfer and preparation.

Recently, we have introduced the single-probe MS technique for in situ MS analysis of live eukaryotic cells in real-time.34,35 The single-probe is an integrated microscale sampling and ionization device that can be coupled with MS for multiple applications. The tip (6–10 μm) of the single-probe can be directly inserted into single cells for direct liquid-extraction of cellular contents followed by immediate MS detection. This technique has been used to analyze cellular metabolites of single cancer cells treated with drugs.35 In addition, the single-probe can be used for other applications, including high spatial resolution ambient MS imaging of biological samples.34,36

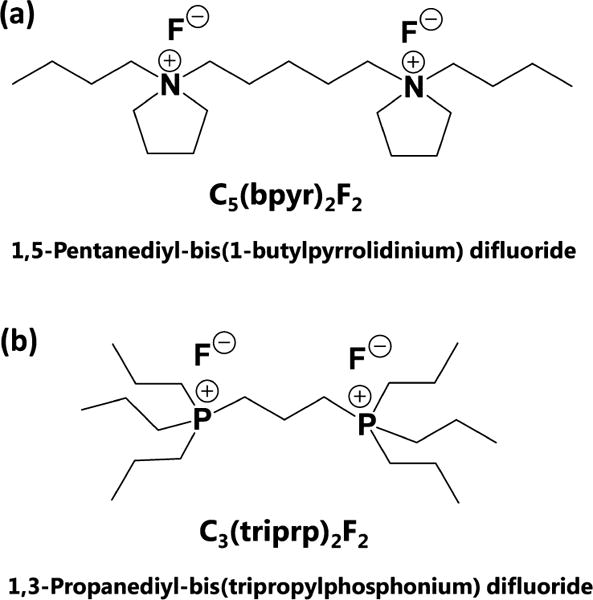

In general, the ionizable cellular metabolites are detected either as cations or anions, and experiments are sometimes conducted in both ionization modes to improve detection coverage.37 However, this type of analysis can be challenging for SCMS due to the extremely small amount of cellular content that is available from a cell (typically ~1 picoliter),1,31 making repeated analyses of the same cell an impractical procedure. To maximize the amount of information from a SCMS experiment, we have developed the reactive single-probe SCMS method, in which dicationic compounds are used as reagents to improve the detection coverage and the number of molecular assignments. Dicationic compounds, sometimes referred to as ionic liquids,38 are synthetic molecules with two positive charges (2+ charged) that readily form ion-paring adducts with a wide range of anions (1− charged), such that the adducts (overall 1+ charged) can be detected in positive ionization mode MS.39 Dicationic compounds have been successfully used in electrospray ionization (ESI) MS (i.e., paired ion ESI (PIESI)), where a variety of negatively charged species, such as phospholipids40 and pesticides,41 were detected in the positive ionization mode, with the increased ion signal intensity compared with the negative ionization mode. Dicationic compounds were also used in desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) MS for the detection of phospholipids in the positive ionization mode,42 where one dicationic compound can selectively enhance the detection sensitivity of relatively small lipids (<400 m/z). These dicationic compounds were later used for DESI MS imaging of biological tissue sections, and the MS images of a number of negatively charged species were obtained in the positive ion mode.43 Recently, two commercially available dicationic compounds, 1,5-pentanediyl-bis(1-butylpyrrolidinium) difluoride (C5(bpyr)2F2, Figure 1a) and 1,3-propanediyl-bis(tripropylphosphonium) difluoride (C3(triprp)2F2, Figure 1b), were used in a single-probe ambient MS imaging study of mouse brain sections to produce high spatial and mass resolution MS images.44 This study indicates that both dicationic compounds readily formed positively charged adducts with a broad range of negatively charged metabolites, allowing MS images of a much larger number of metabolites to be produced from a single experiment than previously possible.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of dicationic compounds (a) C5(bpyr)2F2 and (b) C3(triprp)2F2.

Here, we used these two dicationic compounds, C5(bpyr)2F2 and C3(triprp)2F2, as the reagents to enable the detection of negatively charged metabolites in the positive ionization mode for real-time SCMS analysis. The dicationic compounds were added into the sampling solvent and introduced into individual cells using the single-probe SCMS setup (Figures 2 and S1). We were able to detect a significantly larger number of metabolites when using C5(bpyr)2F2 than using conventional positive or negative ionization modes alone. In particular, this reactive SCMS approach provides higher ion signal intensities for the adducted metabolites. Using a Thermo LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer and the home-built single-probe SCMS setup35 controlled using the LabView software package,45 high mass accuracy MS analyses were performed for tentative molecular assignments (mass error <5 ppm). MS/MS analyses were also carried out to validate assignments of species of interest. Our experimental results indicate that using the dicationic compounds with the single-probe SCMS technique offers a significant improvement of molecular detection from live single cells.

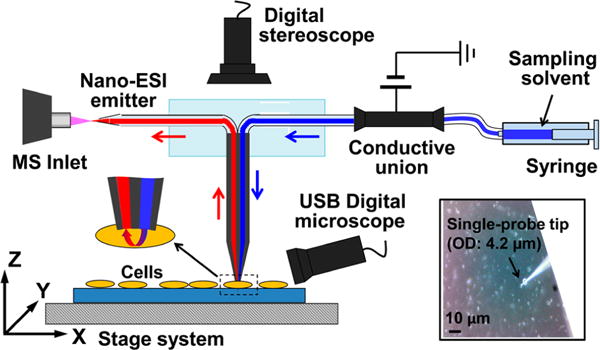

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing of the single-probe SCMS setup. The inset indicates the insertion of a single-probe tip into a cell.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Single-Probe Fabrication Protocol

The fabrication protocols of the single-probe are detailed in our previous publications,34–36 and only brief procedures are provided here. The single-probe is fabricated by combining a laser-pulled (P-2000 Micropipette Laser Puller, Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA) dual-bore quartz tubing (outer diameter (OD) 500 μm; inner diameter (ID) 127 μm, Friedrich & Dimmock, Inc., Millville, NJ, USA) with a fused silica capillary (OD 105 μm; ID 40 μm, Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ, USA) and a nano-ESI emitter that is produced from the same fused silica capillary. A fused silica capillary and a nano-ESI emitter are embedded into a dual-bore quartz needle and sealed using UV curing resin (Light Cure Bonding Adhesive, Prime-Dent, Chicago, Il, USA).

SCMS Experiment and Data Processing

The operation details of the single-probe apparatus can be found in our previous publications,34,35 and only outlined information is provided here. The single-probe SCMS apparatus includes a single-probe, two digital microscopes, a computer-controlled XYZ-translation stage system, and a Thermo (Waltham, MA) LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Figure 2). The cell containing glass slide is attached to the motorized XYZ-stage controlled using software.45 Upon finding a target cell, the Z-stage is precisely lifted (0.1 μm increment) for cell insertion monitored using microscopes. Cellular contents are extracted by the continuously flowing sampling solvent and drawn by the capillary action toward the nano-ESI emitter, where the extracted molecules are immediately ionized for MS analysis (Figure S1). Significant changes of mass spectra can be observed during the cell insertion: ion signals change from the solvent background to the culture medium and then to cellular metabolites. MS analyses were performed using the following parameters: mass resolution 60,000 (at m/z 400), 3.5 kV (positive mode) or −4 kV (negative mode), 1 microscan, 100 ms max injection time, and AGC on (5.0 × 105 ions). The sampling solution was prepared by adding [C5(bpyr)2]2+ or [C3(triprp)2]2+ to acetonitrile. The concentration of these two compounds was varied from 10 μM to 1 mM, and the optimal concentration was found to be 500 μM, which results in the highest ion intensities of most adducts. During the SCMS experiments, the sampling solution was delivered using a syringe pump at a flow rate of ~25 nL/min; the actual flow rate needs to be optimized for each single-probe device. Each cell analysis takes around 30 s, and before the next cell analysis the sampling solvent continuously flows (e.g., for ~3 min) to flush the probe until the MS signals return to the solvent background. Accurate mass metabolite searching was conducted using the online database Metlin from the Scripps Center for Metabolomics (https://metlin.scripps.edu/index.php). Data analyses from three independent SCMS experiments were combined to give a more robust list of tentatively assigned metabolites. For more confident identification of species of interest, MS/MS analyses were conducted using collision induced dissociation (CID) with the following parameters: isolation width 1.0 m/z (±0.5 m/z window) and normalized collision energy 20–35 (manufacturer’s unit).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection of Negatively Charged Metabolites in the Positive Ionization Mode Using Dicationic Compounds

HeLa (human cervical cancer) cell line was used as the model system (refer to the Supporting Information for cell culture protocols) in four sets of experiments: positive ion mode, negative ion mode, and positive ion mode with reagents [C5(bpyr)2]2+ and [C3(triprp)2]2+. Data analyses of each set of experiments were conducted using results obtained from three independent SCMS experiments, and a tentative assignment was given when a common metabolite was found from all three cells. All molecular species reported here were obtained after deisotoping and declustering peaks, i.e., eliminating duplicated assignments of the same metabolite from different ions (protonated and complexes with metal ions or dicationic reagents). Venn diagrams indicating the overlapped assignments among different experiments are shown in Figure S5.

First, we conducted the single-probe SCMS experiments in both positive and negative ion (without adding the dicationic compounds to the sampling solvent) modes as controls. In the positive ion mode, the abundant biomolecules include a variety of phosphatidylcholines (PCs), phosphoethanolamines (PEs), and sphingomyelins (SMs); they were observed as the protonated species ([M + H]+) or sodium adducts ([M + Na]+) in the 600–900 m/z range (Figure S2). A total of 149 unique metabolites were tentatively assigned from common peaks found in three independent SCMS experiments (Table 1); a detailed list can be found in the Supporting Information (Table S1). In the negative ion mode, a wide range of phospholipids, such as PEs, phosphatidic acids (PAs), phosphatidylglycerols (PGs), phosphatidylserines (PSs), and sphospatidylinositols (PIs), can be detected as the deprotonated species ([M – H]−) (Figure S3), with a total of 124 common metabolites tentatively assigned from three independent SCMS experiments (refer to Table S2 for details). Typically, certain types of phospholipids can only be analyzed in the negative ion mode since they readily form negatively charged ions during the ESI process. However, the negative ion mode can be more susceptible to corona discharge,46 which may lead to poorer spray stability and lower ion sensitivity; therefore, it is less commonly used than the positive ion mode in MS analyses.46,47 A possible solution to this obstacle is to rapidly switch instrument polarities during the analysis, so that both the positively and negatively charged ions are detected from the same sample.37 However, this operation mode is impractical for most types of mass spectrometers, and the sample amount extracted from a cell is too small for multiple measurements.

Table 1.

Number of Metabolites Tentatively Assigned (with Mass Error <5 ppm) from Single Cells

| ionization mechanisma | anionsb | cationsc | totald |

|---|---|---|---|

| +ve | N/A | 149 | 149 |

| −ve | 124 | N/A | 124 |

| +ve with [C5(bpyr)2]2+ | 192 (42) | 93 (39) | 285 |

| +ve with [C3(triprp)2]2+ | 70 (23) | 73 (14) | 143 |

Control positive (+ve) and negative (−ve) ionization modes and positive ion mode using dicationic compounds (+ve with [C5(bpyr)2]2+ and + ve with [C3(triprp)2]2+).

Metabolites detected as nonadduct anions (−ve) or 1+ charged adducts (+ve with dicationic compounds). Numbers in parentheses indicate the common species detected in negative ion mode (−ve).

Metabolites detected as nonadduct cations. Numbers in parentheses indicate the common species detected in positive ion mode (+ve).

Total number of assigned metabolites. For the full list of molecules refer to Tables S1–S6.

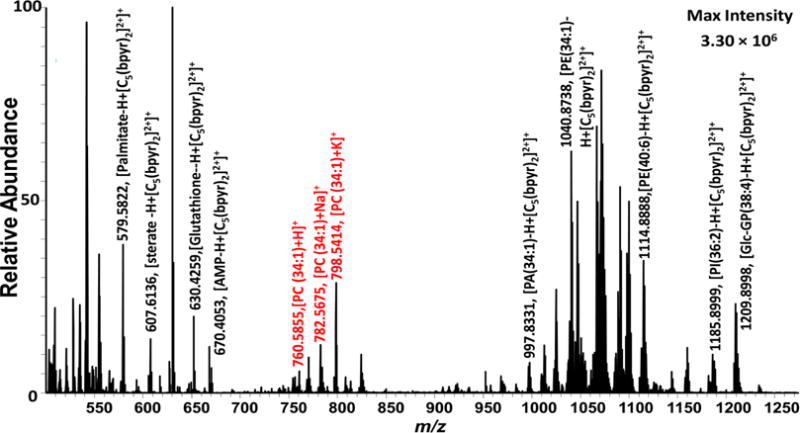

Second, we used the sampling solvents containing [C5(bpyr)2]2+ or [C3(triprp)2]2+ for the experiment. Using the [C5(bpyr)2]2+ reagent, the negatively charged (i.e., singly deprotonated) metabolites form adducts, leading to a mass shift of 324.3504 m/z. Similarly, for [C3(triprp)2]2+ the negatively charged metabolites associate with the dicationic ligand, with a mass shift of 362.3231 m/z. Certain metabolites normally observed in the positive ionization mode, such as [PC (34:1) + Na]+ (782.5675 m/z), can still be detected with their usual m/z values (600–900 m/z) while using the dicationic reagents (Figure 3 for [C5(bpyr)2]2+ and Figure S4 for [C3(triprp)2]2+). The dicationic compounds were not detected due to their m/z values being outside of the mass range used here.

Figure 3.

Mass spectrum of a HeLa cell in the positive ionization mode (using [C5(bpyr)2]2+) with tentative assignment (mass error <5 ppm). Peaks labeled with red text are ions also found in control positive ionization mode (without using [C5(bpyr)2]2+), whereas those labeled with black text are adducts of [C5(bpyr)2]2+.

For SCMS experiments with [C5(bpyr)2]2+, a total of 192 negatively charged common metabolites were tentatively assigned from three independent SCMS experiments after the subtraction of the dication’s mass shift (324.3504 m/z) from each peak (Table 1, for the full list refer to Table S3). Among all 192 species, 42 common metabolites were detected in the control negative ion mode (Table 1, for the full list refer to Tables S2 and S3). From the same spectra, 93 unique positively charged nonadduct metabolites were also detected, and the combined analyses provide 285 common metabolites detected from three cells (Table 1, for the full list refer to Tables S3 and S4). The peak intensities of the [C5(bpyr)2]2+ adducts were generally higher than those corresponding anions in the negative ionization mode. We were also able to detect some important metabolites as adducts, such as adenosine monophosphate (AMP, C10H14N5O7P), which were not detected in the negative ion mode.

For [C3(triprp)2]2+, a total of 70 negatively charged metabolites were detected as adducts from three independent SCMS experiments, and they were tentatively assigned after the subtraction of the mass of the dication (362.3231 m/z) from the detected masses (Table 1, for the full list refer to Table S5). Among all 70 assigned species, 23 common metabolites were detected in the control negative ionization mode (Table 1, for the full list refer to Tables S2 and S5). The same spectra also displayed 73 unique positively charged nonadduct metabolites (Table S6), and a total of 143 metabolites with tentative assignments from these three SCMS experiments. In general, the ion intensities of adducts with [C3(triprp)2]2+ were relatively lower than those with [C5(bpyr)2]2+, which may explain the lower number of detected metabolites. Using [C3(triprp)2]2+ we were able to detect a number of biologically important metabolites, such as folic acid (C19H19N7O6) and 5-amino-6-uracil (C9H15N4O9P), that were not detected in the negative ion mode.

It is evident that the adduct formation enables the detection of a large number of negatively charged species that cannot be observed using negative ionization MS analysis, and the enhanced molecular detection provides complementary information on intracellular chemical profiles. However, adding reagents into the solvent generally results in more complicated mass spectra due to the increased number of peaks. In addition, the numbers of positively charged species for both dicationic compounds were smaller than those found in the control experiment (149 found in the control positive SCMS analysis compared to 93 for [C5(bpyr)2]2+ and 73 for [C3(triprp)2]2+, Table 1), which may have been due to ion suppression from the relatively high concentrations of dicationic compounds (500 μM) used. In our previous single-probe MS imaging studies using these two dicationic compounds, we have also found that the nonadduct ions have relatively lower intensities compared with those observed in experiments without using the dicationic compounds.44 Similar ionization suppression effects are likely to be also present in the SCMS results. Further work is needed to prepare the optimal dicationic compound solutions to maximize the number of metabolite detections for both negatively and positively charged metabolites.

The structure of a dicationic reagent has a significant influence on the molecules that can be detected as adducts. These two dicationic reagents possess different selectivity toward the formation of adducts, and the number of common metabolites tentatively assigned as adducts is 34, which represents a relatively small portion among all assigned metabolites using [C5(bpyr)2]2+ (192) and [C3(triprp)2]2+ (70) (Table 1, for the full list refer to Tables S3 and S5). It follows that dicationic compounds with different structures possess a variable selectivity for adducts formation, as has been shown previously,42 and they can potentially be designed for the detection of different classes of cell metabolites.

Differentiate Low-Abundance Metabolites with Similar m/z Values

Cells contain a complex collection of metabolites in an extremely small volume, and detecting a broad coverage of molecules, particularly those at low abundance, from such a small sample can be very challenging. Although systematically characterizing figures of merit of single-probe SCMS techniques is nontrivial and beyond the scope of current study, we selected two common cellular lipids (PG(16:0–18:1) and PC(16:0–18:1)) as examples and evaluated their limit of detection (LOD), at which signal/noise ≥3. The LOD of PG(16:0–18:1) is about 1.0 μM (detected as protonated species), and using the [C5(bpyr)2]2+ reagent can greatly enhance its detection sensitivity (30 nM, detected as [PG(16:0–18:1) − H + [C5(bpyr)2]2+]+). However, the LOD of PC(16:0–18:1) is about 5.0 nM (detected as protonated species) regardless of using the [C5(bpyr)2]2+ reagent. Our experimental results indicate that using a dicationic reagent may enhance the detection sensitivity of certain cellular compounds.

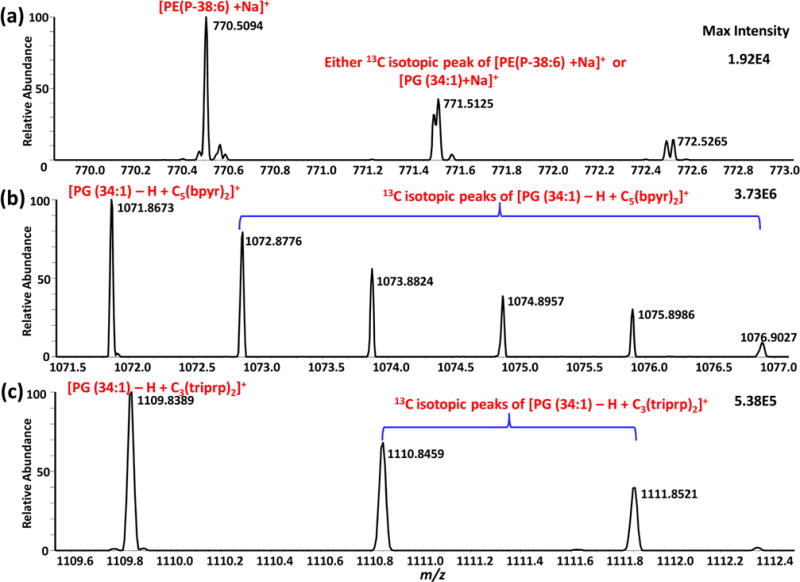

In our experiments many observed ion signal intensities of low-abundance species are comparable with the noise level (e.g., signal/noise <3), or they can even be hidden by being overlapped with other more abundant species possessing similar m/z values. Fortunately, the addition of the dicationic compounds causes a mass shift and an increase in ion intensity of some species, such that an enhanced MS assignment can be obtained. For example, in the detection of PG (34:1) using positive ionization mode, the peak of [PG (34:1)+Na]+ (771.5152 m/z) cannot be distinguished from one of the 13C isotopic peaks of PE(P-38:6) ([C43H74NO7P+Na]+ (771.5125 m/z) (Figure 4a), where ion signals have relatively low intensities (1.92 × 104). In fact, a resolving power of ~290,000 or greater is needed to discriminate these two ions. However, this requirement greatly exceeds the capability of the instrument used in the current study: the maximum resolving power of the Thermo LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer is 100,000 (at 400 m/z). By using [C5(bpyr)2]2+ in the SCMS experiment, a mass shift of 324.3504 occurs, allowing [PG (34:1) − H + [C5(bpyr)2]2+]+ to be observed at 1071.8672 m/z (Figure 4b) with the ion intensity of almost 200 times higher (3.73 × 106) than previously observed without using this dicationic compound (1.92 × 104). In contrast, no dicationic adducts were formed with PE(P-38:6), i.e., this molecule was detected as [C43H74NO7P+Na]+, such that the detection of PG (34:1) was not affected by the presence of PE(P-38:6). Similarly, by adding [C3(triprp)2]2+ to the solvent, with a mass shift of 362.3231, [PG (34:1) − H + [C3(triprp)2]2+]+ can be seen at 1109.8389 m/z (Figure 4c) with ~28 times higher intensity than observed in the positive mode (5.38 × 105). These examples demonstrate the advantages of utilizing dicationic reagents to enhance the detection of low-abundance metabolites with similar molecular weights in single cell analysis.

Figure 4.

Elucidating the PG (43:1) peak using dicationic compounds. (a) [PG (34:1) + Na]+ (771.5152 m/z) is indistinguishable from a 13C isotopic peak of [PE(P-38:6) + Na]+ (771.5125 m/z). (b) Detection of [PG (34:1) − H + [C5(bpyr)2]2+]+ (1071.8672 m/z) using [C5(bpyr)2]2+. (c) Detection of [PG (34:1) − H + [C3(triprp)2]2+]+ (1109.8389 m/z) using [C3(triprp)2]2+. PE(P-38:6) was detected [C43H74NO7P+Na]+ (771.5125 m/z) in both experiments using the dicationic compounds (not shown).

Single Cell MS/MS Analysis of Metabolites Adducted with Dicationic Compounds

Although high resolution MS has been used for molecular analysis, false positive results can be possibly obtained with the achievable mass accuracy (mass error <5 ppm) in current study. Thus, MS/MS experiment analysis is necessary for more confident molecular identification. However, it is expected that MS/MS experiments will be more challenging due to the limited amount of contents from single cells. Using the single-probe SCMS technique, the MS signal of each cell can typically last for ~30 s, allowing MS/MS information to be gathered from the selected ions. To demonstrate the MS/MS analysis capability for the single-probe SCMS technique, we have conducted experiments on a number of adducts of cell metabolites.

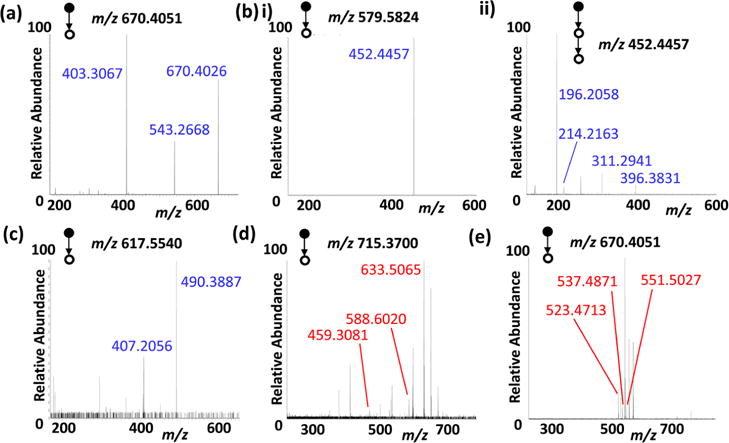

For the adduct of AMP with [C5(bpyr)2]2+ (670.4051 m/z), the fragmentation pattern shows major peaks at 403.3067 m/z and 543.2668 m/z (Table 2, Figure 5a). The peak at 403.3067 m/z, which resulted from a neutral molecule loss (C10H13N5O4, 267.0984 Da), is a phosphate group adducted with the dicationic compound ([PO3− + [C5(bpyr)2]2+]+). The peak found at 543.2668 m/z is formed through a neutral loss of C8H17N (127.1383 Da) from [C5(bpyr)2]2+ itself, leading to the formation of a positively charged ion that was subsequently detected (Figure S6). Interestingly, this result suggests that a covalent bond is likely formed between the [C5(bpyr)2]2+ backbone and phosphate group on AMP through structural rearrangement during the adduct fragmentation.

Table 2.

Summary of CID Fragments of Dicationic Compound Adducts [AMP − H + [C5(bpyr)2]2+]+ (670.4051 m/z), [Palmitic acid − H + [C5(bpyr)2]2+]+ (579.5824 m/z), [Palmitic acid − H + [C3(triprp)2]2+]+ (617.5540 m/z), [5-Amino-6-uracil − H + [C3(triprp)2]2+]+ (715.3700 m/z), and [Folic acid − H + [C3(triprp)2]2+]+ (802.4588 m/z)

| metabolite | dication compound | observed adduct (m/z) | fragment (m/z) | neutral loss (Da) | fragment ion formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | [C5(bpyr)2]2+ | 670.4051 | 543.2668 | 127.1383 | [AMP + [C5(bpyr)2]2+ − H − C8H16N]+ |

| 403.3067 | 267.0984 | [AMP + [C5(bpyr)2]2+ − H − C10H13N5O4]+ | |||

| palmitic acid | [C5(bpyr)2]2+ | 579.5824 | 452.4457 | 127.1367 | [palmitic acid + [C5(bpyr)2]2+ − H − C8H16N]+ |

| MS3 of 452.4457 m/z | [C5(bpyr)2]2+ | 452.4457 | 396.3831 | 56.0626 | [palmitic acid + [C5(bpyr)2]2+ − H − C8H16N − C4H8]+ |

| 311.2941 | 141.1516 | [palmitic acid + [C5(bpyr)2]2+ − H − C8H16N − C10H21•]+ | |||

| 214.2163 | 238.2294 | [palmitic acid + [C5(bpyr)2]2+ − H − C8H16N − C16H30O]+ | |||

| 196.2058 | 256.2399 | [palmitic acid + [C5(bpyr)2]2+ − H − C8H16N − C16H30O2]+ | |||

| palmitic acid | [C3(triprp)2]2+ | 617.5540 | 490.3887 | 127.1653 | [palmitic acid + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − C9H19•]+ |

| 407.2056 | 210.3484 | [palmitic acid + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − C15H30]+ | |||

| 405.2281 | 212.3259 | [palmitic acid + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − C13H24O2]+ | |||

| 5-amino-6-uracil | [C3(triprp)2]2+ | 715.3700 | 633.5065 | 81.8635 | [5-amino-6-uracil + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − H3PO3]+ |

| 588.6020 | 126.7680 | [5-amino-6-uracil + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − C4H5N3O2]+ | |||

| 459.3081 | 256.0619 | [5-amino-6-uracil + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − C9H12N4O5]+ | |||

| folic acid | [C3(triprp)2]2+ | 802.4588 | 551.5027 | 250.9561 | [folic acid + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − C12H13NO5]+ |

| 537.4871 | 264.9717 | [folic acid + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − C12H13N2O5•]+ | |||

| 523.4713 | 278.9875 | [folic acid + [C3(triprp)2]2+ − H − C13H15N2O5•]+ |

Figure 5.

Single cell MS/MS analysis of selected ions. (a) [AMP − H + [C5(bpyr)2]2+]+ (670.4051 m/z), (b) (i) [palmitic acid − H + [C5(bpyr)2]2+]+ (579.5824 m/z) and (ii) the MS3 of the peak found at 452.4457 m/z, (c) [palmitic acid − H + [C3(triprp)2]2+]+ (617.5540 m/z), (d) [5-amino-6-uracil − H + [C3(triprp)2]2+]+ (715.3700 m/z), and (e) [folic acid − H + [C3(triprp)2]2+]+ (802.4588 m/z).

MS/MS fragmentation analyses were performed for adducts of palmitic acid with both [C5(bpyr)2]2+ (579.5824 m/z) and [C3(triprp)2]2+ (617.5540 m/z). The MS/MS fragmentation patterns for [C5(bpyr)2]2+ produced a single peak at 452.4457 m/z due to a neutral loss of C8H17N (127.1367 Da) from [C5(bpyr)2]2+, which is similar to that observed from the AMP adduct (Figure 5b(i)). MS3 fragmentation of this peak yielded a number of fragments due to further neutral losses of C4H8 (56.0626 Da), C10H21• (141.1516 Da), C16H30O (238.2294 Da), and C16H30O2 (256.2399 Da) (Table 2, Figures 5b(ii) and S7). Different neutral losses, C9H19• (127.1653 Da) and C15H30 (210.3484 Da), were observed from MS/MS of the [C3(triprp)2]2+ adduct (Table 2, Figures 5c and S8).

MS/MS analysis was also performed for the adduct of 5-amino-6-uracil with [C3(triprp)2]2+ (715.3700 m/z) as shown in Figures 5d and S9. The fragmentation patterns showed neutral losses of H3PO3 (81.9316 Da), C4H5N3O2 (126.8440 Da), and C9H12N4O5 (256.1437 Da) (Table 2).

Lastly, the MS/MS experiment of the adduct of folic acid with [C3(triprp)2]2+ (802.4588 m/z) yielded neutral molecule losses including C12H13NO5 (250.9561 Da), C12H13N2O5• (264.9717 Da), and C13H15N2O5• (278.9875 Da) (Table 2c, Figures 5e and S10).

Our studies indicate that both dicationic compounds were retained in the fragments of adducts, suggesting that the molecular interactions between the dicationic compounds and the negatively charged molecules are fairly strong. It is possible to gain general fragmentation patterns and detailed information from dicationic compound adducted metabolites to elucidate the structure of the species of interest. Further MS/MS fragmentation analyses are needed to validate all tentatively assigned cell metabolites. However, comprehensive MS/MS studies would be very challenging due to the time constraints of experiments conducted at the single cell level, where signals only last around 30 s from each cell. Therefore, it is suggested that MS/MS analysis be applied only to species of interest during single cell experiments.

CONCLUSION

A novel reactive SCMS method that can directly and quickly unveil the molecular composition of living single cells was implemented. This method combined the microextraction based single-probe SCMS techniques with the application of dicationic reagents, which are added in the sampling solvent for the extraction of cellular contents. Two dicationic compounds, [C5(bpyr)2]2+ and [C3(triprp)2]2+, have been tested in our experiments, and both reagents can form adducts (1+ charged) with the deprotonated metabolites (1− charged) present inside of the cell. With this new approach, we were able to use the positive ionization mode to detect negatively charged cell metabolites, along with the positively charged nonadduct ions, in one SCMS experiment. In particular, most of these negatively charged cell metabolites cannot be detected using negative ionization mode. The total number of negatively charged species tentatively assigned using [C5(bpyr)2]2+ and [C3(triprp)2]2+ is 192 and 70, respectively, which brings the total number of assigned metabolites (including positively charged nonadduct molecules) to 285 and 143, respectively. [C5(bpyr)2]2+ was shown to be a better reagent for the detection of negatively charged metabolites. In addition, these dicationic compounds possess the selectivity for the complex formation, allowing for the elucidation of low-abundance ions with nearly identical m/z values. Single cell MS/MS analyses of selected metabolite adducts have been performed to investigate the general fragmentation patterns and to obtain more confident assignments. The MS/MS results also suggest that the interaction between the dicationic compounds and the target molecules can be strong enough to survive through the fragmentation processes. For future work, different dicationic compounds with different molecular structures can be tested, including tri- and tetracationic compounds, which may offer different and improved capabilities for the sensitive detection of cell metabolites or drug molecules in SCMS studies.40,48

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Anthony Burgett and Naga Rama Kothapalli (the University of Oklahoma) for providing the HeLa cells. This research was supported by grants from the Research Council of the University of Oklahoma Norman Campus, the American Society for Mass Spectrometry Research Award (sponsored by Waters Corporation), Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (Grant HR 14–152), and National Institutes of Health (R01GM116116).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01284.

Experimental section, Figures S1–S10, and Tables S1–S6 (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Schmid A, Kortmann H, Dittrich PS, Blank LM. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zenobi R. Science. 2013;342(6163):1243259. doi: 10.1126/science.1243259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschuler SJ, Wu LF. Cell. 2010;141(4):559–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasdekis AE, Stephanopoulos G. Metab Eng. 2015;27:115–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narsinh KH, Sun N, Sanchez-Freire V, Lee AS, Almeida P, Hu S, Jan T, Wilson KD, Leong D, Rosenberg J, Yao M, Robbins RC, Wu JC. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(3):1217–1221. doi: 10.1172/JCI44635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell AA, Talasaz AH, Zhang H, Coram MA, Reddy A, Deng G, Telli ML, Advani RH, Carlson RW, Mollick JA, Sheth S, Kurian AW, Ford JM, Stockdale FE, Quake SR, Pease RF, Mindrinos MN, Bhanot G, Dairkee SH, Davis RW, Jeffrey SS. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e33788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dominguez MH, Chattopadhyay PK, Ma S, Lamoreaux L, McDavid A, Finak G, Gottardo R, Koup RA, Roederer M. J Immunol Methods. 2013;391(1–2):133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue Z, Huang K, Cai C, Cai L, Jiang CY, Feng Y, Liu Z, Zeng Q, Cheng L, Sun YE, Liu JY, Horvath S, Fan G. Nature. 2013;500(7464):593–597. doi: 10.1038/nature12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wills QF, Mead AJ. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(R1):R74–84. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin-Fernandez ML, Clarke DT. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(11):14742–14765. doi: 10.3390/ijms131114742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kann B, Offerhaus HL, Windbergs M, Otto C. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2015;89:71–90. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polat AN, Ozlu N. Analyst. 2014;139(19):4733–4749. doi: 10.1039/c4an00463a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubakhin SS, Romanova EV, Nemes P, Sweedler JV. Nat Methods. 2011;8(4s):S20–S29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svatos A. Anal Chem. 2011;83(13):5037–5044. doi: 10.1021/ac2003592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Junot C, Fenaille F, Colsch B, Bécher F. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2014;33(6):471–500. doi: 10.1002/mas.21401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong TH, Tillmaand EG, Makurath M, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Biochim Biophys Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2015;1854(7):732–740. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun L, Zhu G, Yan X, Dovichi NJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17(5):795–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boggio KJ, Obasuyi E, Sugino K, Nelson SB, Agar NYR, Agar JN. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2011;8(5):591–604. doi: 10.1586/epr.11.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zavalin A, Todd EM, Rawhouser PD, Yang J, Norris JL, Caprioli RM. J Mass Spectrom. 2012;47(11):1473–1481. doi: 10.1002/jms.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Passarelli MK, Newman CF, Marshall PS, West A, Gilmore IS, Bunch J, Alexander MR, Dollery CT. Anal Chem. 2015;87(13):6696–6702. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ostrowski SG, Kurczy ME, Roddy TP, Winograd N, Ewing AG. Anal Chem. 2007;79(10):3554–3560. doi: 10.1021/ac061825f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibanez AJ, Fagerer SR, Schmidt AM, Urban PL, Jefimovs K, Geiger P, Dechant R, Heinemann M, Zenobi R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(22):8790–8794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209302110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanni EJ, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. J Proteomics. 2012;75(16):5036–5051. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong TH, Kissick DJ, Jansson ET, Comi TJ, Romanova EV, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Anal Chem. 2015;87(14):7036–7042. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Passarelli MK, Ewing AG, Winograd N. Anal Chem. 2013;85(4):2231–2238. doi: 10.1021/ac303038j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stolee JA, Vertes A. Anal Chem. 2013;85(7):3592–3598. doi: 10.1021/ac303347n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrestha B, Sripadi P, Reschke BR, Henderson HD, Powell MJ, Moody SA, Vertes A. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemes P, Knolhoff AM, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3(10):782–792. doi: 10.1021/cn300100u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onjiko RM, Moody SA, Nemes P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(21):6545–6550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423682112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gong X, Zhao Y, Cai S, Fu S, Yang C, Zhang S, Zhang X. Anal Chem. 2014;86(8):3809–3816. doi: 10.1021/ac500882e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizuno H, Tsuyama N, Harada T, Masujima T. J Mass Spectrom. 2008;43(12):1692–1700. doi: 10.1002/jms.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizuno H, Tsuyama N, Date S, Harada T, Masujima T. Anal Sci. 2008;24(12):1525–1527. doi: 10.2116/analsci.24.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Foreman DP, Grant PA, Shrestha B, Moody SA, Villiers F, Kwak JM, Vertes A. Analyst. 2014;139(20):5079–5085. doi: 10.1039/c4an01018c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao W, Pan N, Yang Z. J Vis Exp. 2016;112:e53911. doi: 10.3791/53911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan N, Rao W, Kothapalli NR, Liu R, Burgett AW, Yang Z. Anal Chem. 2014;86(19):9376–9380. doi: 10.1021/ac5029038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao W, Pan N, Yang Z. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26(6):986–993. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong A, Sagar DR, Ortori CA, Kendall DA, Chapman V, Barrett DA. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(9):1902–1913. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M048694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheldrake GN, Schleck D. Green Chem. 2007;9(10):1044–1046. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu SG, Chen D, Letcher RJ. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218(44):8083–8088. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dodbiba E, Xu C, Payagala T, Wanigasekara E, Moon MH, Armstrong DW. Analyst. 2011;136(8):1586–1593. doi: 10.1039/c0an00848f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu C, Armstrong DW. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;792:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao W, Mitchell D, Licence P, Barrett DA. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2014;28(6):616–624. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lostun D, Perez CJ, Licence P, Barrett DA, Ifa DR. Anal Chem. 2015;87(6):3286–3293. doi: 10.1021/ac5042445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao W, Pan N, Tian X, Yang Z. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2016;27(1):124–134. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1287-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas M, Heath BS, Laskin J, Li DS, Liu E, Hui K, Kuprat AP, van Dam KK, Carson JP. 2012 Annual International Conference of the Ieee Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (Embc) 2012:5545–5548. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6347250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cech NB, Enke CG. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2001;20(6):362–387. doi: 10.1002/mas.10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santos IC, Guo H, Mesquita RB, Rangel AO, Armstrong DW, Schug KA. Talanta. 2015;143:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greer T, Sturm R, Li L. J Proteomics. 2011;74(12):2617–2631. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.