Abstract

Forebrain serotonin relevant for many psychological disorders arises in the hindbrain, primarily within the dorsal and median raphe nuclei (DR and MR). These nuclei are heterogeneous, containing several distinct groups of serotonin neurons. Here, new insight into the afferent and efferent connectivity of these areas is reviewed in correlation with their developmental origin. These data suggest that the caudal third of the DR, the area originally designated B6, may be misidentified as part of the DR as it shares many features of connectivity with the MR. By considering the rostral DR independently and affiliating the B6 to the MR, the diverse subgroups of serotonin neurons can be arranged with more coherence into two umbrella groups, each with distinctive domains of influence. Serotonin neurons within the rostral DR are uniquely interconnected with brain areas associated with emotion and motivation such as the amygdala, accumbens and ventral pallidum. In contrast serotonin neurons in the B6 and MR are characterized by their dominion over the septum and hippocampus. This distinction between the DR and B6/MR parallels their developmental origin and likely impacts their role in both behavior and psychopathology. Implications and further subdivisions within these areas are discussed.

Keywords: dorsal raphe, median raphe, depression, hippocampus, 5-HT1A receptor, feedback

Serotonin neurotransmission is associated with many psychopathologies including but not limited to, depression, anxiety, panic, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorders, phobias, drug addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder. With few exceptions, forebrain serotonin neurotransmission implicated in these disorders arises from the B5–B9 cell groups corresponding to the pontine raphe (B5), dorsal raphe (DR; combined B6 and B7), caudal linear nucleus (Cli), median raphe (MR; B8), and supralemniscal area (B9). The ability of this small set of neurons to have a pervasive effect on behavior has fostered the view that serotonin is, as least to some extent, a non-specific modifier of brain and behavior.

Yet it is also true that within these groups of serotonin neurons there is some level of specificity and organization into functional subunits. Indeed, elegant studies combining molecular characteristics with physiological endpoints, electrophysiology and hodological analysis now reveal the potential for highly specialized functional modules in the serotonin system (Brust et al. 2014). The concept of functional specificity is particularly attractive to the field because it provides a framework for understanding how serotonin could contribute to different behaviors and different psychopathologies. For example, dysfunction of a particular subcomponent could generate obsessive-compulsive disorder while dysfunction of another could yield major depression. However, with respect to the ascending system and motivated behavior this scheme remains somewhat speculative since the extent of specification and the identity of the functionally relevant units remain poorly resolved.

Functional specificity related to emotional state can be difficult to pin down: Does a mouse explore a maze differently because it is anxious, tired, satiated, hot, hallucinating or has a migraine? All of these states are influenced by serotonin. In lieu of more compelling data, differences in cytoarchitecture have inspired the definition of multiple subsets of serotonin neurons. The rodent DR alone can be subdivided into as many as 9 different regions (Hale and Lowry 2011). However, cytoarchitecture has an indirect relationship to function that is not always easy to interpret.

There is an anatomical feature that is directly related to function however and that is connectivity (Sporns 2011). At a reduced level, a neuron is defined by it’s input, computational function and output. Input in the form of synaptic potentials brings information about internal and external conditions dictating when a neuron may be called into action. Output defines a neuron’s ability to engage downstream effectors. Therefore connectivity can give a unique insight into functional role. In terms of connectivity however, while it’s known that there is an internal organization of efferents of the serotonin system, they are seen as promiscuous and widespread with complex internal logic.

This problem is evident in the poor dissociation between the MR and DR, the two major groups of ascending serotonin neurons. It is difficult to articulate unique features of the MR, functional or anatomical, without disclaimers that acknowledge the potential overlap of DR. The MR is involved in circadian rhythmicity, but the DR may also play a role (Jacobs and Fornal 1999; Yamakawa and Antle 2010; Meyer-Bernstein and Morin 1999; Morin 1999). The MR is involved in ingestion, but DR neurons fire in synchrony with oral-buccal movements (Fornal et al. 1996; Wirtshafter 2001). Activation of the MR disrupts hippocampal theta, but neurons in the DR also innervate the septum and hippocampus (Vertes 1991; Kocsis and Vertes 1992; Vertes 1981; Vertes et al. 2004).

Recent Advances in Connectivity Reveal Two More Distinct Systems

A series of recent studies using mice have come together to provide new insight into the organization of the ascending serotonin system. Specifically they have strengthened the distinction between the MR and DR by identifying afferents that preferentially innervate each region. Shifting the affiliation of the caudal third of the DR, originally designated B6, to the MR (B8), rather than to the remaining rostral DR (B7) can substantially enhance the distinction between these two major groups of neurons in terms of connectivity. The B6 region lies caudal to the decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle and is indicated on the Paxinos’ atlases as DR-Caudal (the dorsal component) and DR-Interfasicular (the ventral component) (Paxinos and Watson 1998; Paxinos and Franklin 2004). B6 can typically be found medial to the cholinergic laterodorsal tegmental nucleus and the GABAergic dorsal tegmental nucleus (of Gudden). Rostrally the transition to B7 is marked by the appearance of the lateral-wing groups of serotonin neurons.

Recently serotonin-neuron specific retrograde tract-tracing studies identified differences in the afferent innervation of DR and MR serotonin neurons (Pollak Dorocic et al. 2014; Ogawa et al. 2014). Previously afferent innervation into the MR and DR was thought to be largely equivalent, or at least arising from the same sources (Vertes and Linley 2008). Ogawa et al. concisely summarize these differences by noting that lateral structures, such as ventral pallidum and extended amygdala, preferentially innervate the DR, whereas midline regions (medial septum, retromamillary nucleus, interpeduncular nucleus) prefer the MR (Ogawa et al. 2014)(Summarized schematically in Fig. 1). Thus, MR and DR activity is controlled by different streams of neural information and as a consequence, they can be called into action under different behavioral circumstances.

Figure 1.

Simplified schematics illustrating the two distinct limbs of ascending serotonin system and their preferentially targets (single-headed arrows), which often provide reciprocal innervation (double-headed arrows). A. The rostral two-thirds of the DR (rDR,), the largest group of serotonin neurons, is the primary source of serotonin axons in regions such as the cortex (CTX) and extended amydala (AMG) (red and purple arrows). (ACB = nucleus accumbens, VP = ventral pallidum, LH = lateral hypothalamus, Th = thalamus, SN = substantia nigra, VTA = ventral tegmental area, VMM = ventromedial medulla). B. Septo-hippocampal serotonin arises overwhelmingly from the B6 (the caudal third of the DR) and the MR including the pontine raphe (B5) (MS = medial septum, LS = lateral septum, HF = hippocampal formation). Other connections, often reciprocal, of B6/MR are with the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN), retromamillary nucleus (RM, previously called the supramammillary nucleus), LH, suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), medial and lateral habenula (Hb) and paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT). Descending cortical control from the anterior cingulate and lateral orbital cortex (ACA, ORB) is weighted towards B6/MR, whereas prelimbic and agranular insular cortices (PL, AI) prefer the rDR. C. Combined schematic comparing salient ascending features of the rDR vs. B6/MR.

Combined with these studies was an analysis of how axons from many different brain regions distributed locally within the MR and DR (Commons 2015). Specifically, by applying an informatics analysis on a library of anterograde tract tracing experiments, we could identify common patterns in how afferents distribute within subregions of the MR and DR (Fig. 2). We found that many afferents had dense innervation of the rostral 2/3 of the DR (B7), but dissipated upon reaching the caudal third of the DR (B6) (Fig. 2). On the other hand, afferents that preferentially innervated the MR tended to extend into and ramify within B6 (Fig. 2). As a result of these patterns, unsupervised clustering analysis found that the B6 region was more similar in afferent innervation to the MR than to the remaining rostral DR (Fig. 3) (Commons 2015).

Figure 2.

Examples of differential afferents to the rostral DR vs. the MR and B6 (the caudal DR) from the Allen Brain Connectivity Atlas (Oh et al. 2014). Sections at 6 different levels from rostral (left) to caudal (right). A. Afferents from the substantia nigra reticulata (SNR) and B. agranular insula (AI) preferentially innervate the rostral 2/3 of the DR (arrows). These axons tend to dissipate at the caudal pole of the nucleus (B6, arrowheads). C. Afferents from the anterior cingulate cortex (ACA) and D. lateral habenula (LHb) are heavy in the MR (arrows) and continue their trajectory dorsal to innervate B6 (the caudal DR). Similar patterns occur in many different afferents to these areas (Commons 2015). Image credit: Allen Institute for Brain Science. Bar = 150 um.

Figure 3.

Grouping serotonin neurons by commonalities of afferent innervation. A. Six different levels of the hindbrain showing areas of the dorsal and median raphe from rostral (A1) to caudal (A6). Bar = 150 um. B. Regions of interest within those areas, colorized by their similarities in afferent innervation revealed by clustering analysis diagramed in C. Most of the midline DR areas cluster together (yellow) and these regions have similarities with lateral DR locations (orange). The B6 areas (green) are more similar to the MR (green) in afferent innervation then the remaining rostral DR (yellow/orange). (Modified and reprinted from Commons, JCN).

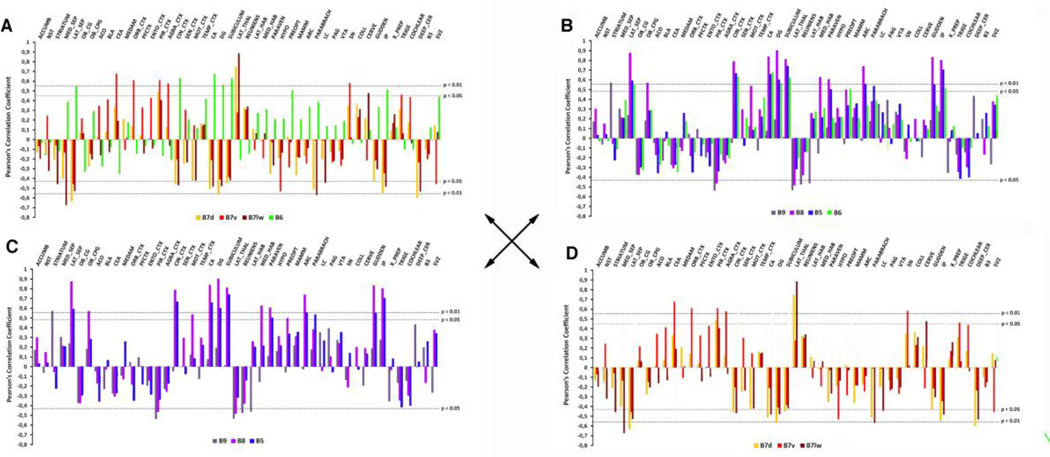

These studies of afferents to the MR and DR coincided with new insight into ascending projections from these areas. Conditional viral anterograde tract tracing methods recently showed that, like inputs, output projections from the DR preferred areas located more laterally (amygdala, cerebral cortex, striatum, substantia nigra, etc.), whereas the MR favored the hippocampus, septum and other medial areas (Muzerelle et al. 2014)(Figs. 4, 5). Interestingly, correlations between location of injection sites within different raphe subregions (B5–B9) and their forebrain targets revealed similarities in the projections of B6 and those of the MR (B8), which together contrasted to remaining rostral DR projection targets (B7)(Fig. 4)(Muzerelle et al. 2014). These findings in the mouse reinforce now classic studies in the rat that showed that forebrain projections from the DR were organized along a rostro-caudal axis (Imai et al. 1986).

Figure 4.

Forebrain projections from B6 are similar to those of the MR and distinct from the remaining DR projections. Using serotonin-neuron specific anterograde tract tracing, innervation of specific targets was correlated to origin within different raphe subnuclei (Muzerelle et al. 2014). Positive or negative Pearson’s correlation coefficients shown in relation to horizontal lines indicating the threshold for significance at different levels. A. B6 (green) correlations plotted in comparison to the remaining DR (B7 dorsal, ventral and lateral) show B6 and B7 tend to innervate different areas. B. B6 correlations plotted in comparison to B9, B8 and B5 show more commonalities of forebrain projections. C. B9, 8 and 5 plotted independently. D. B7 subregions plotted in the absence of B6 show more internal homogeneity (compare D with A). (Modified and reprinted from (Muzerelle et al. 2014)).

Figure 5.

Comparison of anterograde tract tracing from an injection site capturing the rostral two thirds of the DR (A), but not the caudal DR or B6 region (B) using serotonin-neuron specific viral anterograde labeling; and from the MR (C) using a non-cell-type-specific tracer from the Allen Brain Connectivity Atlas (Oh et al. 2014). While individual examples are not definitive, these illustrate unique characteristics of output projections of the rostral DR vs. MR. D. Axons in the rostral DR primarily ascend through the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) towards the ventral forebrain and cortex. Innervation of sensory areas (olfactory bulb, OB, lateral geniculate LG, and superior colliculus, SC) as well as motor areas (hypoglossal nucleus, XII) is visible. E. A dorsal view of the same projection shows inclusion of the amygdala (central nucleus, CEA,) substantial innominata (SI), submedial nucleus of the thalamus (SMT) and locus coeruleus (LC). F. Ascending projections from the MR have a similar ascending trajectory through the LHA, but then form two loops. The smaller loop goes through the stria medullaris to innervate the medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus, lateral part (MDl) and habenula. The larger loop innervates the septal complex (S) and continues to the hippocampus (HF). G. A dorsal view of the same case shows some additional areas of innervation, for example the entorhinal cortex (ETC) and raphe obscurus (RO). Image credit: Allen Institute for Brain Science.

Projection Patterns Coincide with Developmentally Defined Areas

The distinct connectivity of the rostral and caudal DR may well be generated by differences in their developmental origin within the hindbrain. The rostral DR, B6 and part of the MR share developmental origin within a prepontine domain defined by the expression of Engrailed-1 (En1), often referred to as rhombomere 1 (r1) (Jensen et al. 2008; Fox and Deneris 2012). However, this domain can be further divided by developmental patterns of gene expression into a rostral area known as the isthmus (rhombomere 0 (r0); identified as the isthmic part of r1 by some authors) and a caudal part, referred to as r1 proper. A recent developmental analysis refined the En1 molecular fate-mapping data and illustrated that the rostral part of the DR arises from the isthmus whereas the caudal DR (B6) originates within r1 proper, as does the rostral portion of the MR (Alonso et al. 2013). Thus, new information on differential afferents, efferents and developmental origin converge to link B6 to the MR and distinguish it from the DR.

As a distinct domain the isthmus (r0) has received relatively little attention with respect to DR development due to the lack of distinguishing molecular tools. However, a recent analysis of serotonin-neuron gene expression patterns supports the idea that serotonin neurons in this area are distinct from their neighbors arising in r1 proper in the MR. Specifically, some of the genes that are expressed at higher levels in En1-defined DR (r0/r1) than in En1-defined MR (r1) serotonin neurons include Pax5, Foxa1 and En2: all transcription factors with a known relationship to isthmus patterning (Okaty et al. 2015). Differential expression of these or other transcription factors associated with r0 vs. r1 proper could give rise to parallel down-stream differences in the genetic profile of serotonin neurons in the rostral vs. caudal DR and MR. Indeed, distinctions in r0/r1 DR vs. r1 MR serotonin neurons are evident in expression of genes that fall into the categories of G-protein coupled receptors, cell adhesion molecules, ion channels and synaptic transmission. One gene that is present in MR yet sparse in the DR is Met (Okaty et al. 2015). While only a single gene, detailed analysis shows that Met is expressed in both B6 and MR, but absent from the rostral DR (Okaty et al. 2015; Wu and Levitt 2013), a striking coincidence with the developmental and hodological similarity between B6 and the MR.

The rapid interneuromeric transition between the rostral and caudal DR visible with the new tract tracing studies stands in contrast to the more common conception that the DR exhibits rostral-caudal gradients in attributes. Technical limitations coupled with interpretations that disregarded the neuromeric organization may have conspired to create the illusion that these areas are two extremes on a continuous gradient. Moreover, any technique that depends on local injections, such as tract tracing, is limited by the size and characteristics of the injection site. At the same time, serotonin neurons of different developmental lineages intermix over a few hundred microns at their interfaces (Bang et al. 2012; Jensen et al. 2008) and there is no barrier to the spread of tracers or other substances at these interfaces. A spherical injection site placed at different rostro-caudal locations in the DR will gradually include more of one area then the other, thus generating the appearance of a gradient. Therefore individual cases of tract-tracing may report that the rostral DR (B7) contributes to projections in the hippocampus, but over many injections, inclusion of B7 will show no correlation with the presence of hippocampal afferents (Muzerelle et al. 2014).

In Dahlstrom and Fuxe’s original description of monoamine containing neurons, the serotonin (B) cell groups were described by location in the medulla oblongata (B1–4) pons (B3, B5–6) and mesencephalon (B7–B9) (Dahlstrom and Fuxe 1964). However as a consequence of advances in developmental biology, the definition of the pons and mesencephalon was corrected. In fact neither the MR nor DR are now considered mesencephalic structures, but rather derivatives of the rostral prepontine hindbrain. With the shifting definitions of these areas, B6 became commonly merged with B7, as the relationship between B6 and MR is not obvious in the coronal view. However it can be seen in sagittal sections (Fig. 6) and when similarities were noted between the MR and B6 in the literature, they were often illustrated in sagittal section (Imai et al. 1986; Alonso et al. 2013; Molliver 1987).

Figure 6.

A. In a sagittal view, the B6 and MR (B8) are contiguous and aligned with respect to developmental orientation (arrowheads, compare to Alonso et al., 2013), caudal to the decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle (xscp, labeled ‘x’). Coronal sections, which are oblique to the relevant developmental orientation, visually disconnect B6 from the MR and make it appear more related to the rostral DR. The caudal linear nucleus (CLi) is rostral to the xscp and ventral to the DR (B7). R3-pontine raphe (PnR, B5) lies at the caudal pole of the MR. Major caudal groups, raphe magnus (B3, RMg), obscurus (B2, Rob) and pallidus (B1, RPa) are also visible. (Adult mouse tissue immunolabeled for the serotonin synthetic enzyme, tryptophan hydroxylase using an antiserum from Novus Biologicals NB100-74555. Projection view of widefield images of 3–100 um-thick sagittal sections.) Bar = 0.5 mm B. Schematic representation of the major groups of serotonin neurons.

Character of the Circuits

One of the primary roles of serotonin is in motivated behavior, either in pursuit of reward or in avoidance of punishment. More specifically serotonin is often associated with the latency to engage a motivated action. Serotonin is commonly referred to in playing a role in behavioral inhibition, or “..enabling the organism to arrange and tolerate delay before acting” (Soubrie 1986). Likewise, serotonin has long been associated with the degree of impulsivity (Stein et al. 1993). More recent studies have discussed the role of serotonin in generating patience to wait for rewards (Miyazaki et al. 2014; Miyazaki et al. 2012) or in anticipation of either reward or punishment (Rygula et al. 2014).

Forebrain areas investigated for the role of serotonin in reward and punishment include ventral limbic forebrain affective and motivation-related areas such as the amygdala, ventral striatum, and ventral pallidum as well as cortical areas. In addition, meso-diencephalic dopamine systems are critical in these processes. All of these brain areas are highly interconnected to the rostral DR, B7, (Ogawa et al. 2014; Pollak Dorocic et al. 2014; Weissbourd et al. 2014; Muzerelle et al. 2014; Vertes and Linley 2008) and some studies have directly implicated the DR in motivated behavior (Liu et al. 2014; Cohen et al. 2015). Likewise serotonin neurons in the DR appear to encode both appetitive and aversive information (Hayashi et al. 2015).

Connectivity of the rostral DR exhibits ‘small world’ features, that is, many areas that innervate the DR receive reciprocal connections from the DR, or they are interconnected with each other. The central nucleus of the amygdala has the largest preference to innervate the DR (over the MR) (Ogawa et al. 2014; Pollak Dorocic et al. 2014) and both the central and basolateral nuclei of the amygdala receive return innervation from the same area (Muzerelle et al. 2014). In addition, the rostral DR has reciprocal connections with both the VTA and its target area in the ventral striatum (McDevitt et al. 2014; Vertes 1991; Commons 2015). In another illustration of small world features, VTA dopamine and DR serotonin neurons appear to receive similar streams of afferent innervation from regions within the hypothalamus, extended amygdala and basal ganglia (Ogawa et al. 2014).

A second major theme is the involvement of serotonin in regulating hippocampal function. The hippocampus plays two critical roles in normal brain function: in the formation of declarative memory and as the major feedback regulator of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. On a short time course, serotonin has the capacity to disrupt theta rhythm in the hippocampus (reviewed by (Vertes and Kocsis 1997)) and, over longer time scales, to influence dentate gyrus neurogenesis (Diaz et al. 2013; Banasr et al. 2004; Malberg and Duman 2003; Santarelli et al. 2003; Encinas et al. 2006). Tract tracing studies both in the rat and the mouse converge to show that these serotonin projections arise from the B6 and MR with only rare exception (Muzerelle et al. 2014; Vertes and Linley 2008; Imai et al. 1986).

Likewise, B6 and MR are the overwhelming sources of serotonin to the septal complex (Muzerelle et al. 2014; Vertes and Linley 2008; Bang et al. 2012). The medial septum provides reciprocal innervation to the MR and B6 (Ogawa et al. 2014; Commons 2015). These serotonin neurons also preferentially receive innervation from the retromamillary nucleus, interpeduncular nucleus and lateral habenula. While the medial septum and the retromamillary nucleus (previously called the supramammillary nucleus) are well known as key regulators of hippocampal theta (Crooks et al. 2012; Kocsis and Vertes 1996; Maru et al. 1979; Pan and McNaughton 2004; Vertes and Kocsis 1997; Kirk and Mackay 2003), the lateral habenula, interpeduncular nucleus and the pathway between them (the fasiculus retroflexus) are also implicated (Funato et al. 2010; Valjakka et al. 1998; Aizawa et al. 2013; Goutagny et al. 2013; Kinney et al. 1994). Thus again, ‘small world’ features are evident within these networks in that many afferents and efferents associated with B6/MR are also related to hippocampal function.

While regulation of the hippocampus appears a salient feature common to both B6 and MR, these areas also receive direct connections from the lateral habenula suggesting they may be engaged consequent to punishment or lack of reward (Matsumoto and Hikosaka 2009). This is consistent with a role for the MR in conditioned aversion (Amo et al. 2014). Aversive stimuli also appear to engage B6 as forced swim, precipitated withdrawal and inescapable stress all activate Fos expression in serotonin neurons in this region (Commons 2008; Sperling and Commons 2011; Grahn et al. 1999). MR and B6 neurons are also interconnected with the suprachiasmatic nucleus (Bang et al. 2012; Yamakawa and Antle 2010), and have been associated with non-photic phase shifts in diurnal rhythm (Meyer-Bernstein and Morin 1999; Yamakawa and Antle 2010).

Individual Cell Types vs. Families of Cell Types

Each of the two umbrella groups envisioned encompasses large groups of neurons with known internal heterogeneity and extensive domains of innervation. Some heterogeneity is related to cytoarchitecture (Hale and Lowry 2011). Additional heterogeneity in the form of identifiable cell-types can be revealed with genetic or other approaches (Gaspar and Lillesaar 2012; Fernandez et al. 2015; Okaty et al. 2015; Jensen et al. 2008). In order to further divide serotonin neurons into subgroups that are truly useful in providing a greater understanding into how serotonin in sum regulates brain function, we need to know more about the relative relationships these groups have to each other, because not all identifiable groups of neurons may be equally different from each other. The methods to systematically identify relative relationships are available in the form of clustering and principal component analysis. The substrates for identifying relationships should involve the basic determinants of a neuron’s role in a network: input, computational function and output, and increasingly refined data within these domains are now emerging. While behavioral role may provide compelling criteria independently, it is a complex one that should be applied with caution, given the capacity of serotonin to influence mood, emotion, sensation, cognition as well as many physiological endpoints.

The trends in connectivity reviewed here happen to fully agree with the predicted rhombomeric ascription of the rostral 2/3 of the DR to the isthmus (r0) and the B6, like the rostral part of the MR, to r1 proper. This agreement is important, because it implicitly provides a causal background (segmental differential genetic specification) for the observed hodological disparities, which are not explainable otherwise. While the rostral DR appears to be united by it’s developmental origin in r0, caudal portions of the MR are developmentally distinct, arising from r2 (also called prepontine raphe). In addition, r3-derived serotonin neurons (pontine raphe, B5) are sometimes classified as the caudal border of the MR (Jacobs and Azmitia 1992). Each of these areas has known distinctive projection features (Bang et al. 2012; Mikkelsen et al. 1997). Yet B6 and the entire MR including the prepontine and pontine raphe areas are united in their contribution to septo-hippocampal serotonin, suggesting some relationship. The similarity between r1-MR and r2-MR extends to transcriptional profile, an endpoint arguably related to both connectivity and computational function. However, by that measure r3-derrived neurons are more distinctive (Okaty et al. 2015). Therefor it may be reasonable to expect that these areas (B6, r1-MR r2-MR, and r3-pontine raphe) are not functionally homogenous in their control of septo-hippocampal, or brain function, as some evidence would already indicate (Okaty et al. 2015). On that note, although the ability of the MR to desynchronize hippocampal theta is long-standing, this effect appears location-sensitive and is best elicited by stimulating the central region of the MR (Bland, 2015).

Feedback Could Promote Complimentary Activity States

The identification of different afferents to the rostral DR in contrast to B6/MR indicates that these two general areas may be active under different behavioral conditions, a conclusion supported by evidence in the literature. For example serotonin neurotransmission contributes to the behavioral effects of both nicotine exposure and nicotine withdrawal, seemingly opposite behavioral states (Cheeta et al. 2001; Carboni et al. 1988; Rasmussen et al. 1997). Nicotine exposure activates Fos in serotonin neurons located in the rostral DR, but not more caudally in B6. In contrast, nicotine withdrawal activates Fos in B6 serotonin neuron, but not in more rostral DR serotonin neurons (Fig. 7) (Sperling and Commons 2011). Thus, distinct behavioral states produced by nicotine exposure and withdrawal correlate with activation of different sets of serotonin neurons, which would have the capacity to effect regional changes in serotonin signaling in the forebrain. These observations are broadly consistent with the idea that the lateral habenula could exert opponent control over different groups of serotonin neurons (Ogawa et al. 2014) although the circuits involved have not been identified.

Figure 7.

Nicotine exposure and withdrawal produce reciprocal patterns of activation and 5-HT1A-receptor-dependent inhibition as assayed by Fos expression within serotonin neurons shown at three rostro-caudal levels in coronal section (rostral top-left). A. After chronic nicotine exposure, an acute nicotine treatment activates serotonin neuron-Fos at the rostral pole of the DR (red). At the same time, there is evidence for 5-HT1A receptor-dependent inhibition at caudal pole of the DR (B6, blue). B. Precipitated nicotine withdrawal leads to activation of Fos in B6 serotonin neurons (caudal, red), and 5-HT1A mediated inhibition of serotonin neurons located more rostrally in the nucleus (blue). Modified from (Sperling and Commons 2011).

5-HT1A receptors mediate a feedback inhibition of serotonin neurons, and are thought to participate in homeostatic regulation of serotonin neuron activity, tempering changes in activity state. However, the existence of diverse groups of serotonin neurons raises many other possible roles for feedback inhibition. For example communication between different groups of neurons could work in shaping topographic patterns of activity. Specifically, working heterologously one group of neurons could inhibit other groups of neurons with perhaps competing function (Bang et al. 2012). Since different groups of serotonin neurons have preferential targets in the forebrain, heterologous inhibition could help shape the regionally selective changes in extracellular serotonin that are known to occur under different conditions (Kirby and Lucki 1997; Li et al. 2014)

We discovered that in different behavioral states blocking 5-HT1A-dependent feedback has topographically organized effects on serotonin neurons in the MR and DR (Commons 2008). Subsequently, we utilized the acute nicotine exposure and withdrawal models to examine the relationship between regions that are activated vs. inhibited via a 5-HT1A-dependent mechanism. During nicotine exposure (when serotonin neurons are activated rostrally in the DR) we found evidence for 5-HT1A-receptor dependent feedback inhibition of B6. During nicotine withdrawal when B6 neurons are activated, the reciprocal pattern was found, that is, there was evidence for feedback inhibition of the rostral DR (Fig. 7)(Sperling and Commons 2011). This is the first evidence indicating that heterologous inhibition could exist between subgroups of serotonin neurons, which would function not as a homeostatic mechanism, but rather to coordinate activity between different groups of neurons. While it’s possible that indirect multisynaptic mechanisms may underlie these 5-HT1A-dependent mechanism, there are also direct connections between distinct groups of serotonin neurons (Bang et al. 2012).

Implication for Psychopathology

The existence of distinct groups of serotonin neurons as well as evidence that feedback mechanisms could coordinate or balance their activity, together raise the possibility that psychopathology could occur when these systems are thrown out of balance. There are lines of evidence suggesting dysfunction of B6/MR networks in depression in humans or learned helplessness in rodents. In human suicide victims, there are increases in expression of tryptophan hydroxylase and loss of 5-HT1A receptors in the caudal pole of the DR (B6) (Boldrini et al. 2008; Bach-Mizrachi et al. 2008), and activation of the same area in rodents is correlated with learned helplessness (Hammack et al. 2002; Hammack et al. 2003; Valentino et al. 2009). Likewise manipulations that might inhibit activity in B6 increase active coping strategies (McDevitt et al. 2011). Afferents to B6/MR system (orbitofrontal cortex, cingulate cortex) and efferents (hippocampus) are commonly reduced in volume in depression (Arnone et al. 2012; Rive et al. 2013). At the same time, there is thought to be disinhibition of limbic striatum and hyperactive amygdala (Sheline et al. 2001). Taken together, depression could be associated with increased function of B6/MR and hyper-inhibition of hippocampal function, combined with decreased action of the rostral DR and disinhibition of the ventral limbic system. Indeed, based on other lines of evidence, it has previously been speculated that major depression arises from imbalances between the DR and MR activity states (Lechin et al. 2006; Deakin and Graeff 1991).

The idea that there could be imbalances between groups of serotonin neurons would provide a potential explanation for why serotonin selective-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are more effective pharmacotherapy for several disorders than serotonin-mimetics. That is, SSRIs would fundamentally change the balance between interacting subgroups of serotonin neurons in ways that serotonin-mimetics would not replicate. It’s also possible to envisage how bipolar instability could be generated by an imbalance in the dynamics of feedback systems that coordinate the activation states of two divergent systems. Thus, these anatomical insights give rise to new hypotheses for the potential basis of some psychopathological states.

B6 as a Cause of Confusion

Most of the literature on the DR probably reflects study of the rostral 2/3rd of the nucleus or B7, as this corresponds to the largest cluster of neurons, which is often targeted for recordings or local injections. However, inclusion of B6 in the umbrella of the DR could account for some contradictions in the literature. For example, the two recent tract tracing studies examining afferents to DR and MR serotonin neurons differed on their conclusions regarding afferents from the lateral habenula, which either preferred the MR (Ogawa et al. 2014) or DR (Pollak Dorocic et al. 2014). Indeed, the lateral habenula has been known to provide a robust Substance P innervation to the caudal DR for many years (Neckers et al. 1979) and the termination of this projection specifically in the caudal pole of this nucleus, as well as in the MR, was recently reprised (Sego et al. 2014; Quina et al. 2015). Therefore it is possible that differential weighting of the caudal DR in the datasets of the two groups (more by Pollak Dorocic et al. and less by Ogawa et al.) could have generated their distinct conclusions. Likewise, separate consideration of B6 would make it easier to identify meaningful differences between the MR and DR, and it would reduce the problem of intrinsic heterogeneity of the DR. Thus, the current reconsideration of the organization of the ascending serotonin system will lead to improved study design.

Other Ascending Serotonin Neurons

Here we focus on serotonin neurons resident in the two ascending largest nuclei, the DR and MR. There are additional groups of serotonin neurons that innervate the forebrain. These include B9, the supralemniscal nucleus (SuL) serotonin neurons which may be divided into three different groups by developmental origin (r1-, r2- and r3-SuL) (Jensen et al. 2008; Alonso et al. 2013). In the mouse these contribute to serotonin innervation of the dorsal striatum and locus coeruleus (Muzerelle et al. 2014). In addition, a small group of serotonin neurons are recognized ventral to the rostral DR in the caudal linear nucleus (CLi). These are thought to be more related to the DR than the MR (Jacobs and Azmitia 1992).

Conclusions

Recent advances have revealed differences in the connectivity of the DR and MR that are noticeably sharpened by shifting the affiliation of B6 from the DR to the MR. This shift in perspective on the organization of the ascending serotonin system causes two more unique systems to come into focus from what previously appeared to be a single system with more complex gradients in organization. Identification of these two major umbrella groups suggests new roles for feedback inhibitory processes, which are numerous in serotonin neurobiology, and raises the possibility that imbalances between different groups of serotonin neurons could contribute to psychopathology. In addition, these new results identify a cause for confusion and potential contradiction within the literature: that is, as currently conceived the DR is an amalgam of two highly divergent zones.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Patricia Gaspar for generous permission to use a modified figure from Muzerelle et al. as well as for comments on the manuscript. Additional thoughtful comments were provided by Drs. Daniel Ehlinger, Jessica Babb (Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School), Dr. Bernat Kocsis (Beth Israel Deaconess/Harvard Medical School), Dr. Ben Okaty, Dr. Susan Dymecki (Harvard Medical School) and the reviewers; although all omissions, over-simplifications and errors remain my own. Funding provided by the National Institutes of Health grants DA021801 and HD036379, the Brain and Behavior Foundation NARSAD Independent Investigator Award, and the Sara Page Mayo Foundation for Pediatric Pain Research.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Commons has no conflict of interest.

References

- Aizawa H, Yanagihara S, Kobayashi M, Niisato K, Takekawa T, Harukuni R, McHugh TJ, Fukai T, Isomura Y, Okamoto H. The synchronous activity of lateral habenular neurons is essential for regulating hippocampal theta oscillation. J Neurosci. 2013;33(20):8909–8921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4369-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso A, Merchan P, Sandoval JE, Sanchez-Arrones L, Garcia-Cazorla A, Artuch R, Ferran JL, Martinez-de-la-Torre M, Puelles L. Development of the serotonergic cells in murine raphe nuclei and their relations with rhombomeric domains. Brain Struct Funct. 2013;218(5):1229–1277. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0456-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amo R, Fredes F, Kinoshita M, Aoki R, Aizawa H, Agetsuma M, Aoki T, Shiraki T, Kakinuma H, Matsuda M, Yamazaki M, Takahoko M, Tsuboi T, Higashijima S, Miyasaka N, Koide T, Yabuki Y, Yoshihara Y, Fukai T, Okamoto H. The habenulo-raphe serotonergic circuit encodes an aversive expectation value essential for adaptive active avoidance of danger. Neuron. 2014;84(5):1034–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D, McIntosh AM, Ebmeier KP, Munafo MR, Anderson IM. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in unipolar depression: systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach-Mizrachi H, Underwood MD, Tin A, Ellis SP, Mann JJ, Arango V. Elevated expression of tryptophan hydroxylase-2 mRNA at the neuronal level in the dorsal and median raphe nuclei of depressed suicides. Molecular psychiatry. 2008;13(5):507–513. 465. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002143. doi:4002143 [pii] 10.1038/sj.mp.4002143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banasr M, Hery M, Printemps R, Daszuta A. Serotonin-induced increases in adult cell proliferation and neurogenesis are mediated through different and common 5-HT receptor subtypes in the dentate gyrus and the subventricular zone. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(3):450–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang SJ, Jensen P, Dymecki SM, Commons KG. Projections and interconnections of genetically defined serotonin neurons in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(1):85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini M, Underwood MD, Mann JJ, Arango V. Serotonin-1A autoreceptor binding in the dorsal raphe nucleus of depressed suicides. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(6):433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.004. doi:S0022-3956(07)00090-8 [pii] 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust RD, Corcoran AE, Richerson GB, Nattie E, Dymecki SM. Functional and developmental identification of a molecular subtype of brain serotonergic neuron specialized to regulate breathing dynamics. Cell reports. 2014;9(6):2152–2165. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E, Acquas E, Leone P, Perezzani L, Di Chiara G. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists block morphine- and nicotine-induced place-preference conditioning. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;151(1):159–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90710-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeta S, Irvine EE, Kenny PJ, File SE. The dorsal raphe nucleus is a crucial structure mediating nicotine's anxiolytic effects and the development of tolerance and withdrawal responses. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;155(1):78–85. doi: 10.1007/s002130100681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JY, Amoroso MW, Uchida N. Serotonergic neurons signal reward and punishment on multiple timescales. eLife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commons KG. Evidence for topographically organized endogenous 5-HT-1A receptor-dependent feedback inhibition of the ascending serotonin system. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27(10):2611–2618. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commons KG. Two major network domains in the dorsal raphe nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cne.23748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks R, Jackson J, Bland BH. Dissociable pathways facilitate theta and non-theta states in the median raphe--septohippocampal circuit. Hippocampus. 2012;22(7):1567–1576. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrom A, Fuxe K. Localization of monoamines in the lower brain stem. Experientia. 1964;20(7):398–399. doi: 10.1007/BF02147990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin JF, Graeff FG. 5-HT and mechanisms of defence. J Psychopharmacol. 1991;5(4):305–315. doi: 10.1177/026988119100500414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz SL, Narboux-Neme N, Trowbridge S, Scotto-Lomassese S, Kleine Borgmann FB, Jessberger S, Giros B, Maroteaux L, Deneris E, Gaspar P. Paradoxical increase in survival of newborn neurons in the dentate gyrus of mice with constitutive depletion of serotonin. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38(5):2650–2658. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encinas JM, Vaahtokari A, Enikolopov G. Fluoxetine targets early progenitor cells in the adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(21):8233–8238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601992103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez SP, Cauli B, Cabezas C, Muzerelle A, Poncer JC, Gaspar P. Multiscale single-cell analysis reveals unique phenotypes of raphe 5-HT neurons projecting to the forebrain. Brain Struct Funct. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornal CA, Metzler CW, Marrosu F, Ribiero-do-Valle LE, Jacobs BL. A subgroup of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons in the cat is strongly activated during oral-buccal movements. Brain Res. 1996;716(1–2):123–133. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00006-6. doi:0006-8993(96)00006-6 [pii] 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SR, Deneris ES. Engrailed is required in maturing serotonin neurons to regulate the cytoarchitecture and survival of the dorsal raphe nucleus. J Neurosci. 2012;32(23):7832–7842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5829-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funato H, Sato M, Sinton CM, Gautron L, Williams SC, Skach A, Elmquist JK, Skoultchi AI, Yanagisawa M. Loss of Goosecoid-like and DiGeorge syndrome critical region 14 in interpeduncular nucleus results in altered regulation of rapid eye movement sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(42):18155–18160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012764107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P, Lillesaar C. Probing the diversity of serotonin neurons. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367(1601):2382–2394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutagny R, Loureiro M, Jackson J, Chaumont J, Williams S, Isope P, Kelche C, Cassel JC, Lecourtier L. Interactions between the lateral habenula and the hippocampus: implication for spatial memory processes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(12):2418–2426. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn RE, Will MJ, Hammack SE, Maswood S, McQueen MB, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Activation of serotonin-immunoreactive cells in the dorsal raphe nucleus in rats exposed to an uncontrollable stressor. Brain Res. 1999;826(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01208-1. doi:S0006-8993(99)01208-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale MW, Lowry CA. Functional topography of midbrain and pontine serotonergic systems: implications for synaptic regulation of serotonergic circuits. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213(2–3):243–264. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Richey KJ, Schmid MJ, LoPresti ML, Watkins LR, Maier SF. The role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the dorsal raphe nucleus in mediating the behavioral consequences of uncontrollable stress. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):1020–1026. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01020.2002. doi:22/3/1020 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Schmid MJ, LoPresti ML, Der-Avakian A, Pellymounter MA, Foster AC, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Corticotropin releasing hormone type 2 receptors in the dorsal raphe nucleus mediate the behavioral consequences of uncontrollable stress. J Neurosci. 2003;23(3):1019–1025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-01019.2003. doi:23/3/1019 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Nakao K, Nakamura K. Appetitive and aversive information coding in the primate dorsal raphe nucleus. J Neurosci. 2015;35(15):6195–6208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2860-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Steindler DA, Kitai ST. The organization of divergent axonal projections from the midbrain raphe nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1986;243(3):363–380. doi: 10.1002/cne.902430307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72(1):165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Fornal CA. Activity of serotonergic neurons in behaving animals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):9S–15S. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Farago AF, Awatramani RB, Scott MM, Deneris ES, Dymecki SM. Redefining the serotonergic system by genetic lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(4):417–419. doi: 10.1038/nn2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney GG, Kocsis B, Vertes RP. Injections of excitatory amino acid antagonists into the median raphe nucleus produce hippocampal theta rhythm in the urethane-anesthetized rat. Brain Res. 1994;654(1):96–104. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby LG, Lucki I. Interaction between the forced swimming test and fluoxetine treatment on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282(2):967–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk IJ, Mackay JC. The role of theta-range oscillations in synchronising and integrating activity in distributed mnemonic networks. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior. 2003;39(4–5):993–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70874-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis B, Vertes RP. Dorsal raphe neurons: synchronous discharge with the theta rhythm of the hippocampus in the freely behaving rat. Journal of neurophysiology. 1992;68(4):1463–1467. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.4.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis B, Vertes RP. Midbrain raphe cell firing and hippocampal theta rhythm in urethane-anaesthetized rats. Neuroreport. 1996;7(18):2867–2872. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611250-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechin F, van der Dijs B, Hernandez-Adrian G. Dorsal raphe vs. median raphe serotonergic antagonism. Anatomical, physiological, behavioral, neuroendocrinological, neuropharmacological and clinical evidences: relevance for neuropharmacological therapy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(4):565–585. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Scholl JL, Tu W, Hassell JE, Watt MJ, Forster GL, Renner KJ. Serotonergic responses to stress are enhanced in the central amygdala and inhibited in the ventral hippocampus during amphetamine withdrawal. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;40(11):3684–3692. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Zhou J, Li Y, Hu F, Lu Y, Ma M, Feng Q, Zhang JE, Wang D, Zeng J, Bao J, Kim JY, Chen ZF, El Mestikawy S, Luo M. Dorsal raphe neurons signal reward through 5-HT and glutamate. Neuron. 2014;81(6):1360–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malberg JE, Duman RS. Cell proliferation in adult hippocampus is decreased by inescapable stress: reversal by fluoxetine treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(9):1562–1571. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maru E, Takahashi LK, Iwahara S. Effects of median raphe nucleus lesions on hippocampal EEG in the freely moving rat. Brain Res. 1979;163(2):223–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Representation of negative motivational value in the primate lateral habenula. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(1):77–84. doi: 10.1038/nn.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt RA, Hiroi R, Mackenzie SM, Robin NC, Cohn A, Kim JJ, Neumaier JF. Serotonin 1B autoreceptors originating in the caudal dorsal raphe nucleus reduce expression of fear and depression-like behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(8):780–787. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.029. doi:S0006-3223(10)01361-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt RA, Tiran-Cappello A, Shen H, Balderas I, Britt JP, Marino RA, Chung SL, Richie CT, Harvey BK, Bonci A. Serotonergic versus nonserotonergic dorsal raphe projection neurons: differential participation in reward circuitry. Cell reports. 2014;8(6):1857–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Bernstein EL, Morin LP. Electrical stimulation of the median or dorsal raphe nuclei reduces light-induced FOS protein in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and causes circadian activity rhythm phase shifts. Neuroscience. 1999;92(1):267–279. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00733-7. doi:S0306-4522(98)00733-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen JD, Hay-Schmidt A, Larsen PJ. Central innervation of the rat ependyma and subcommissural organ with special reference to ascending serotoninergic projections from the raphe nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 1997;384(4):556–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki K, Miyazaki KW, Doya K. The role of serotonin in the regulation of patience and impulsivity. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;45(2):213–224. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki KW, Miyazaki K, Tanaka KF, Yamanaka A, Takahashi A, Tabuchi S, Doya K. Optogenetic activation of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons enhances patience for future rewards. Current biology : CB. 2014;24(17):2033–2040. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molliver ME. Serotonergic neuronal systems: what their anatomic organization tells us about function. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;7(6 Suppl):3S–23S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin LP. Serotonin and the regulation of mammalian circadian rhythmicity. Annals of medicine. 1999;31(1):12–33. doi: 10.3109/07853899909019259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzerelle A, Scotto-Lomassese S, Bernard JF, Soiza-Reilly M, Gaspar P. Conditional anterograde tracing reveals distinct targeting of individual serotonin cell groups (B5–B9) to the forebrain and brainstem. Brain Struct Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0924-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neckers LM, Schwartz JP, Wyatt RJ, Speciale SG. Substance P afferents from the habenula innervate the dorsal raphe nucleus. Experimental brain research. 1979;37(3):619–623. doi: 10.1007/BF00236830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa SK, Cohen JY, Hwang D, Uchida N, Watabe-Uchida M. Organization of monosynaptic inputs to the serotonin and dopamine neuromodulatory systems. Cell reports. 2014;8(4):1105–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SW, Harris JA, Ng L, Winslow B, Cain N, Mihalas S, Wang Q, Lau C, Kuan L, Henry AM, Mortrud MT, Ouellette B, Nguyen TN, Sorensen SA, Slaughterbeck CR, Wakeman W, Li Y, Feng D, Ho A, Nicholas E, Hirokawa KE, Bohn P, Joines KM, Peng H, Hawrylycz MJ, Phillips JW, Hohmann JG, Wohnoutka P, Gerfen CR, Koch C, Bernard A, Dang C, Jones AR, Zeng H. A mesoscale connectome of the mouse brain. Nature. 2014;508(7495):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature13186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaty BW, Freret ME, Rood BD, Brust RD, Hennessy ML, deBairos D, Kim JC, Cook MN, Dymecki SM. Multi-Scale Molecular Deconstruction of the Serotonin Neuron System. Neuron. 2015;88(4):774–791. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan WX, McNaughton N. The supramammillary area: its organization, functions and relationship to the hippocampus. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74(3):127–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin K. Compact. Second. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4th. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak Dorocic I, Furth D, Xuan Y, Johansson Y, Pozzi L, Silberberg G, Carlen M, Meletis K. A whole-brain atlas of inputs to serotonergic neurons of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei. Neuron. 2014;83(3):663–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quina LA, Tempest L, Ng L, Harris JA, Ferguson S, Jhou TC, Turner EE. Efferent pathways of the mouse lateral habenula. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523(1):32–60. doi: 10.1002/cne.23662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Kallman MJ, Helton DR. Serotonin-1A antagonists attenuate the effects of nicotine withdrawal on the auditory startle response. Synapse. 1997;27(2):145–152. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199710)27:2<145::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-E. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199710)27:2<145::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-E [pii] 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199710)27:2<145::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rive MM, van Rooijen G, Veltman DJ, Phillips ML, Schene AH, Ruhe HG. Neural correlates of dysfunctional emotion regulation in major depressive disorder. A systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(10 Pt 2):2529–2553. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rygula R, Clarke HF, Cardinal RN, Cockcroft GJ, Xia J, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Role of Central Serotonin in Anticipation of Rewarding and Punishing Outcomes: Effects of Selective Amygdala or Orbitofrontal 5-HT Depletion. Cerebral cortex. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, Weisstaub N, Lee J, Duman R, Arancio O, Belzung C, Hen R. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301(5634):805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sego C, Goncalves L, Lima L, Furigo IC, Donato J, Jr, Metzger M. Lateral habenula and the rostromedial tegmental nucleus innervate neurochemically distinct subdivisions of the dorsal raphe nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522(7):1454–1484. doi: 10.1002/cne.23533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI, Barch DM, Donnelly JM, Ollinger JM, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA. Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(9):651–658. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubrie P. Reconciling the role of central serotonin neurons in human and animal behavior. Behav Brain Res. 1986;9(2):319–364. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R, Commons KG. Shifting topographic activation and 5-HT1A receptor-mediated inhibition of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons produced by nicotine exposure and withdrawal. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33(10):1866–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporns O. Networks of the Brain. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Hollander E, Liebowitz MR. Neurobiology of impulsivity and the impulse control disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;5(1):9–17. doi: 10.1176/jnp.5.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Lucki I, Van Bockstaele E. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the dorsal raphe nucleus: Linking stress coping and addiction. Brain Res. 2009;1314:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.100. doi:S0006-8993(09)02090-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjakka A, Vartiainen J, Tuomisto L, Tuomisto JT, Olkkonen H, Airaksinen MM. The fasciculus retroflexus controls the integrity of REM sleep by supporting the generation of hippocampal theta rhythm and rapid eye movements in rats. Brain Res Bull. 1998;47(2):171–184. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes R, Linley S. Efferent and afferent connections of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei in the rat. In: Monti J, Pandi-Perumal S, Jacobs B, Nutt D, editors. Serotonin and Sleep: Molecular, Functional and Clinical Aspects. Switzerland: Birkhauser Verlag; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP. An analysis of ascending brain stem systems involved in hippocampal synchronization and desynchronization. Journal of neurophysiology. 1981;46(5):1140–1159. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.46.5.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP. A PHA-L analysis of ascending projections of the dorsal raphe nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;313(4):643–668. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP, Hoover WB, Viana Di Prisco G. Theta rhythm of the hippocampus: subcortical control and functional significance. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2004;3(3):173–200. doi: 10.1177/1534582304273594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP, Kocsis B. Brainstem-diencephalo-septohippocampal systems controlling the theta rhythm of the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1997;81(4):893–926. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbourd B, Ren J, DeLoach KE, Guenthner CJ, Miyamichi K, Luo L. Presynaptic partners of dorsal raphe serotonergic and GABAergic neurons. Neuron. 2014;83(3):645–662. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtshafter D. The control of ingestive behavior by the median raphe nucleus. Appetite. 2001;36(1):99–105. doi: 10.1006/appe.2000.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HH, Levitt P. Prenatal expression of MET receptor tyrosine kinase in the fetal mouse dorsal raphe nuclei and the visceral motor/sensory brainstem. Developmental neuroscience. 2013;35(1):1–16. doi: 10.1159/000346367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa GR, Antle MC. Phenotype and function of raphe projections to the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31(11):1974–1983. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07228.x. doi:EJN7228 [pii] 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]