Abstract

Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α is a transcription factor that regulates metabolic and immune response genes in the setting of low oxygen tension and inflammation. We investigated the function of HIF-1α in the host response to Histoplasma capsulatum since granulomas induced by this pathogenic fungus develop hypoxic microenvironments during the early adaptive immune response. Here we demonstrated that myeloid HIF-1α-deficient mice exhibited elevated fungal burden during the innate immune response (prior to seven days post-infection) as well as decreased survival in response to a sublethal inoculum of H. capsulatum. The absence of myeloid HIF-1α did not alter immune cell recruitment to the lungs of infected animals but was associated with an elevation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Treatment with mAb to IL-10 restored protective immunity to the mutant mice. Macrophages (Mϕ) constituted the majority of IL-10 producing cells. Deletion of HIF-1α in neutrophils or DCs did not alter fungal burden thus implicating Mϕs as the pivotal cell in host resistance. HIF-1α was stabilized in Mϕ following infection. Increased activity of the transcription factor CREB in HIF-1α-deficient Mϕs drove IL-10 production in response to H. capsulatum. IL-10 inhibited Mϕ control of fungal growth in response to the activating cytokine IFN-γ. Thus, we identified a critical function for Mϕ HIF-1α in tempering IL-10 production following infection. We established that transcriptional regulation of IL-10 by HIF-1α and CREB is critical for activation of Mϕ by IFN-γ and effective handling of H. capsulatum.

Introduction

H. capsulatum is the most common endemic pulmonary mycosis in the United States (1). While immunocompetent hosts typically resolve infection with minimal symptoms, severe infections can develop in immunocompromised individuals. Coordinated activity of the innate and adaptive immune systems is required for fungal growth restriction. Early innate recognition is required for phagocytosis, cytokine production, and recruitment of additional innate cells and adaptive cells. This accumulation and signaling drive development of granulomas. During the initiation of adaptive immunity, granulomas become hypoxic; one of the central transcription factors in the response to hypoxia is HIF-1α (2).

HIF-1 is a multi-subunit transcription factor composed of a constitutively expressed β subunit, HIF-1β/ARNT, and an oxygen labile α subunit, HIF-1α (3). The oxygen-dependent degradation of HIF-1α is controlled via hydroxylation of the oxygen-dependent degradation (ODD) domain (3). Oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing (PHD) enzymes are responsible for hydroxylation of the ODD in the setting of low oxygen (4). Subsequent polyubiquitination leads to recognition by the 26S proteasome and degradation (5, 6). The requirement for O2 as an essential co-factor drives decreased activity in the setting of hypoxia, which is responsible for elevated HIF-1α protein.

Infection with a variety of pathogens has been associated with increased HIF-1α protein and/or expression of downstream targets. LPS can induce HIF-1α expression through increased transcription rather than protein stabilization in the setting of normoxia (7–10). While the mechanism of HIF-1α protein stabilization and/or transcriptional induction is unknown, it accumulates in the setting of infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae, Vesicular Stomatitis virus, Hepatitis B and C, Human Papilloma Virus, Toxoplasma gondii, Leishmania amazonensis, and the fungal pathogens Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans (11–19). These studies suggest that, while HIF-1α plays an undeniable role in the cellular response to hypoxia, it may have been co-opted as a transcription factor in the response to pathogens as well.

HIF-1α regulates numerous genes involved in both innate and adaptive immune responses. This transcription factor has been implicated as a key element in phagocyte and T cell function in response to a wide variety of pathogens (20). In infectious diseases, HIF-1α targets within phagocytes include microbicidal genes as well as soluble mediators that recruit and activate immune cells (21). HIF-1α evokes direct killing of many pathogenic microbes by primary mediators such as reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide (NO), and antimicrobial peptides (22–25). Direct targets of HIF-1α in myeloid cells include the pro-inflammatory molecules TNF-α, IL-12, and CCL2 as well as the anti-inflammatory IL-10 (26–29).

IL-10 inhibits antimicrobial activity of Mϕ by limiting production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates (30–32). In the innate response to H. capsulatum, IL-10 dampens immunity by limiting IFN-γ production; IL-10−/− mice exhibit elevated IFN-γ in association with accelerated H. capsulatum clearance (33). Modulation of IFN-γ by IL-10 attenuates the activation of Mϕ, which need IFN-γ to kill H. capsulatum (34). Although IL-10 is produced by multiple cell populations, myeloid cells are the predominant producer during H. capsulatum infection (35).

The presence of hypoxia and the prominence of HIF-1α in dictating antimicrobial activity, metabolism, and cytokine generation led us to consider the contribution of this transcription factor in the myeloid response to H. capsulatum infection. To this end, we infected myeloid specific HIF-1α knockout mice (Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl) via the pulmonary route with H. capsulatum. The absence of myeloid HIF-1α decreased survival and increased fungal burden as early as day 3 post-infection. The collapse of immunity was not associated with a reduction in lung pro-inflammatory protective cytokines, but rather with an elevation in IL-10. Mϕ, the principal source of this cytokine, were the dominant myeloid cell population required for the phenotype of the mutant mice. Mϕ production of IL-10 was tempered by HIF-1α and depended on enhanced CREB-binding protein (CBP)-driven transcriptional induction. Elevated IL-10 from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl Mϕ prevented IFN-γ driven activation and, thus, enhanced fungal burden relative to control Mϕ. These results demonstrate that HIF-1α is critical for controlling the progression of infection with the fungal pathogen H. capsulatum by limiting IL-10.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male C57BL/6 and breeding pairs of Itgax-cre (C57BL/6 background) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). We thank Dr. Timothy Eubank, Ohio State University, for the Hif1αfl/fl, Lyz2cre, and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice. Itgaxcre and Hif1αfl/fl mice were crossed to generate Itgaxcre Hif1αfl/fl mice. We thank Gang Huang, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, for Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl Hif2αfl/fl. Animals were housed in isolator cages and maintained by the Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine, University of Cincinnati, accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act guidelines of the National Institutes of Health, and all protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Cincinnati.

Preparation of H. capsulatum and infection of mice

H. capsulatum strain G217B and yeast cells of the same strain that express GFP were grown for 72 h at 37 °C as described (36, 37). To infect mice, 6–8 week-old animals were inoculated intranasally with 2×106 yeasts or 2×107 yeasts (indicated as high dose) in ~30 l of Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HyClone, Logan, UT). For in vitro infection, cells were allowed to adhere to plates for 3 h. Cells were infected with 1–5 yeast per Mϕ for the indicated times.

Generation of bone marrow-derived Mϕs (BMDMϕs) and in vitro inhibition

Bone marrow was isolated from tibiae and femurs of 6–10-week-old mice by flushing with HBSS. Cells were dispensed into tissue culture flasks at a density of 1×106 cells/ml of RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1% gentamicin sulfate, 5 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 ng/ml of mouse GM-CSF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Flasks were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Mϕs were harvested at day 7. Non-adherent cells were removed, ice-cold PBS was added, and cells were scraped from the flask. Cells were collected, washed with PBS, and dispensed into culture dishes. For inhibition studies, piceatannol (Tocris, Bristol, UK) was added to Mϕs 90 minutes before infection. For CBP interaction inhibition studies, chetomin (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) was added to Mϕs 30 minutes prior to infection and KG501 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was added 90 minutes before infection.

RNA Isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA from whole lungs of mice was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and from in vitro M cultures using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Oligo(dT)-primed cDNA was prepared by using the reverse transcriptase system (Promega, Madison, WI). Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR analysis was performed using TaqMan master mixture and primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples were analyzed with ABI Prism 7500. The hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase housekeeping gene was used as an internal control. The conditions for amplification were 50 °C for 2 min and 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 sec and 60 °C for 1 min.

Isolation of lung leukocytes

Lungs were homogenized with the gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) in 5ml of HBSS with 2 mg/ml of collagenase D (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and 40U of DNase I (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C. The homogenate was percolated through a 40 mm nylon mesh (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA) and washed three times with HBSS. Leukocytes were isolated by separation on Lympholyte M (Cedarlane, Burlington, ON).

Western blot

Following 24 h of infection, non-adherent cells were washed off with ice cold PBS. Cells were scraped off in ice cold PBS and spun down. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis in SDS/PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were used for immunodetection of HIF-1α (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) and β actin (Santa Cruz).

Confocal microscopy

Following 24 h of infection, BMDMϕs were stained with HIF-1α antibody and DAPI nuclear stain for 30 min. Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM710 confocal and analyzed with ZEN 2011 software.

Organ culture for H. capsulatum

Organs were homogenized in sterile HBSS, serially diluted, and plated onto mycosel-agar plates containing 5% sheep blood and 5% glucose. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. The limit of detection was 102 CFU.

Flow cytometry, cell sorting, and gating strategy

Cells from mouse lungs were incubated with CD16/32 to limit nonspecific binding. Leukocytes were then stained with the indicated antibodies at 4°C for 15–30 min in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.01% sodium azide. Cells were stained with combinations of the following antibodies: FITC-conjugated Ly6G; FITC-conjugated Ly6C; FITC-conjugated CD11c; PerCP-conjugated CD11b; APC-conjugated CD3; PE-conjugated CD4; FITC-conjugated CD8; and APC-conjugated F4/80 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For intracellular IL-10 staining, cells were incubated with Cytofix/ Cytoperm (BD Biosciences), washed in Permeabilization Buffer (BD Biosciences), and stained for 45 min with PE-conjugated IL-10 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). Cells were washed and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde. Isotype controls were used. Data were acquired using BD Accuri C6 cytometer and analyzed using the FCS Express 4.0 Software (DeNovo Software, Los Angeles, CA). For cell sorting experiments, leukocytes from the lungs of Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice were isolated at day 3 or day 7 post-infection using 5 laser FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences) following cell surface staining. Cells were identified using side (SSC-A) and forward scatter (FSC-A), followed by doublet exclusion using forward scatter height (FSC-H) against FSC-A. Cells were subsequently phenotypically characterized by the following surface markers: neutrophils (PMNs) were Ly-6Ghi, CD11b+, F4/80−; dendritic cells (DCs) were F4/80−, CD11b−/+, CD11c+; Mϕ were F4/80+, CD11c−, CD11b+; CD4 T cells were CD3+, CD4+, CD8−; CD8 T cells were CD3+, CD4−, CD8+. As gated here, the Mϕ population does not include interstitial Mϕ or alveolar Mϕ. Gating strategy depicted in Supplemental Fig. 1.

PMN depletion and IL-4 and IL-10 neutralization

PMNs were depleted by i.p. injection of anti-Ly6G mAb (1A8), containing 0.1 mg protein, 24 h prior to infection, and at days 1, 3, and 5 post-infection. PMN depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry staining for Ly6G/C (Nimp14), CD11b, and CD11c in experimental animals. IL-4 was neutralized by i.p. injections of anti-IL-4 (11B11), containing 1 mg protein, at the time of infection and at day 3 post-infection. IL-10 was neutralized by i.p. injections of anti-IL-10 (JES5-2A5), containing 0.25 mg protein, at the time of infection, and at days 3, 5, and 7 post-infection.

Histology

Lungs were inflated, excised, fixed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections (5 m) were stained with H&E. Serial pictures were obtained on an Olympus BX51 microscope and Olympus DP71 camera. Lung sections were reconstructed using Photoshop Photomerge CS5 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Area of inflammation was measured using the measure function in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) in a blinded fashion.

Measurement of cytokines

Cytokines were quantified in lung homogenates and cell-free Mϕ culture supernatants using a Milliplex MAP immunoassay (Millipore, Billerica, MA) following an overnight incubation with the assay beads according to the manufacturer protocol. A minimum of 100 beads were counted for each analyte per well. The beads were analyzed on a Luminex Magpix instrument (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX) using Luminex xPONENT software. Additional analysis was performed utilizing the Milliplex Analyst (Millipore) software.

Griess assay

The quantity of NO in the supernatant of cultured bone marrow derived macrophages was measured using the Griess Reagent System. Briefly, sample aliquots were mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (l% sulfanilamide/0.1% naphthylethylene diamine dihydrochloride/2 % H3PO4). A microplate reader was used to measure the absorbance at 540 nm (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Burlington, VT). NO2− was determined using NaNO2 as a standard. Media background was determined and subtracted from the experimental values. Nitrate was converted into nitrite prior to the reaction with Griess reagent, since nitrite is rapidly oxidized to nitrate.

Statistics

Statistics p values were calculated with one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons and adjusted with Bonferroni’s or Holm Sidak correction and nonpaired Student’s t test where two groups were compared; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; NS, not significant

Results

Myeloid HIF-1α is required for fungal clearance and survival following infection with H. capsulatum

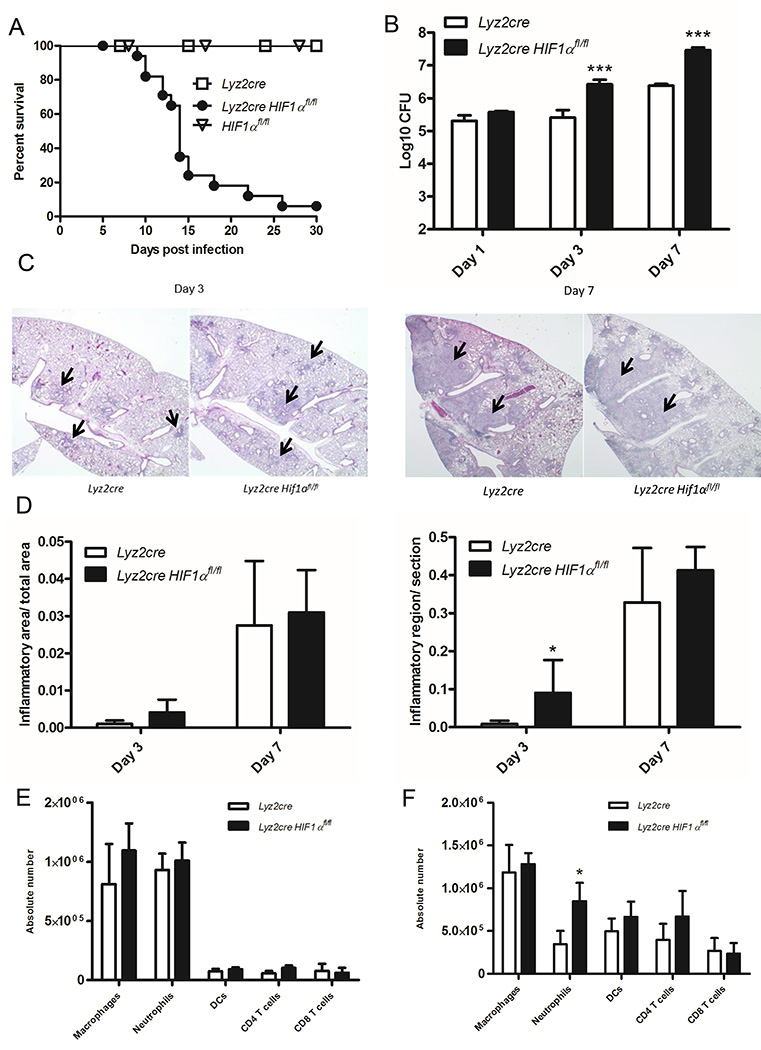

Since HIF-1α regulates production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines known to be essential in response to H. capsulatum, we sought to determine the necessity of this transcription factor within the myeloid cell compartment (38, 39). Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice exhibit HIF-1α deletion within alveolar Mϕs, inflammatory monocytes, monocyte-derived DCs, and PMNs (38). We infected control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice with a sublethal number of H. capsulatum yeast cells. As early as 10 days post-infection, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice began to succumb to infection; by 30 days, over 90% of them died while all control Lyz2cre mice and Hif1αfl/fl mice survived (Fig. 1A). To assess if the decreased survival in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice was associated with an enhanced fungal burden, we measured the number of organisms in lungs at 1, 3, and 7 days post-infection. Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice exhibited a striking increase in fungal burden relative to controls as early as 3 days and through 7 days post-infection (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Mϕ HIF-1α expression is required for murine survival during H. capsulatum infection. A, Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice were infected and survival recorded when mice were moribund. (n=10–18 mice/group; representative of five experiments) B, Lungs were harvested at days 1, 3, and 7 post-infection to determine the number of CFUs. Data represent the mean ± SD (n=8–12 mice/group; representative of three experiments). C, Representative images of lung sections stained with H&E taken at 100× (C) magnification at 3 and 7 days post-infection. (n=5 mice/group; 3 experiments) D, Quantification of inflammatory area/total area and regions of inflammation/section. (n=5 mice/group; 3 experiments) E and F, Lung leukocytes were isolated and counted at days 3 and 7 post-infection. (n=6 mice/group; 4 experiments) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

Cell recruitment and expansion are unaltered in HIF-1α knockout mice

To elucidate any alterations in the organization of the inflammatory response, we evaluated the amount of inflammation in histopathology sections of lung tissue from infected control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice at 3 and 7 days post-infection (Fig. 1C). At day 3, both control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice exhibited acute peribronchiolar inflammation; the area of involvement in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice was increased relative to control mice (Fig. 1D). By 7 days the inflammation had coalesced into consolidation in both groups; there was no difference in the area between control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice.

While we saw no change in the inflamed area at day 7, we speculated that the lack of HIF-1α might alter specific leukocyte populations since it is required for optimal immune cell recruitment (38, 40, 18). To examine the composition of inflammatory cell populations, we stained lungs at days 3 and 7 post-infection for Mϕs, PMNs, DCs, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Absolute cell numbers in each of these populations were unaltered relative to control at 3 days post-infection (Fig. 1E). PMNs were elevated at day 7 post-infection, but the numbers of other populations were similar between the two groups of mice (Fig. 1F). These results suggested that cell recruitment and expansion following infection do not explain the elevated fungal burden and decreased survival of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice.

Lack of HIF-1α in myeloid cells enhances production of IL-10

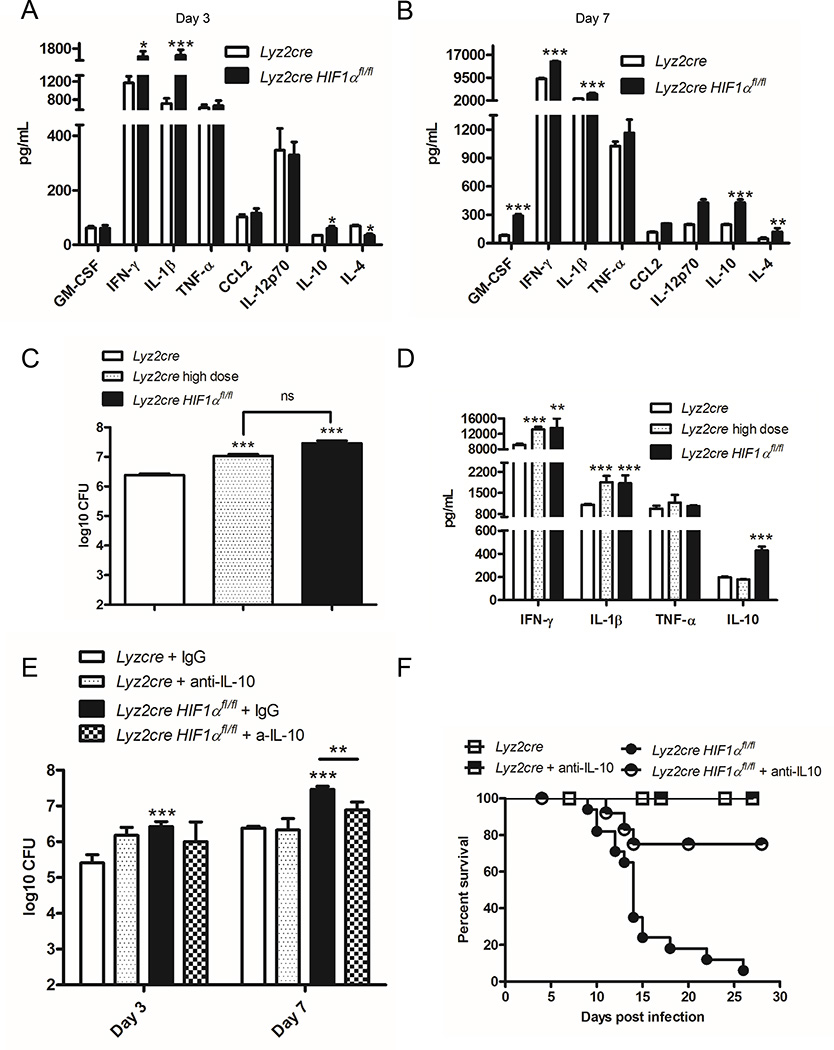

Since inflammatory cell recruitment was not deficient in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice, we surveyed cytokines that are known to be important in the murine response to H. capsulatum in lung homogenates at 3 and 7 days post-infection. Relative to controls, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl murine lungs exhibited an elevation in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 as well as prototypically protective cytokines IFN-γ and IL-1β as early as day 3 post-infection (Fig. 2A) (36, 41, 42). No change in TNF-α or GM-CSF between the two groups was observed on day 3 post-infection or in any cytokines prior to infection (Fig. 2A, data not shown). At 7 days of infection, the lungs of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice manifested elevated production of IL-10, IFN-γ, IL-1β, GM-CSF and IL-4 (Fig. 2B). The IL-10 concentration at day 7 post-infection in lungs of the Itgaxcre mice (202 ± 13 pg/mL, n=4) did not differ (p>0.05) from that of infected controls (197 ± 6 pg/mL, n=8).

FIGURE 2.

Elevated IL-10 in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice drives the increased fungal burden and decreased survival relative to control. Protein concentrations were determined in lung homogenates at days 3 (A) and 7 (B) post-infection. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. (n = 8–12 from 3 experiments) C, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl were infected with 2×106 yeasts intranasally; Lyz2cre were infected with 2×106 or 2×107 (high dose) yeasts intranasally. Lungs were harvested at day 7 post-infection to determine the number of CFUs. The CFUs of the high dose and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl groups were compared to the control and to each other. (n=6–8 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) D, IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-10 protein concentrations in lung homogenates were determined at day 7 post-infection. (n=6–8 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) E, Following administration of IL-10 neutralizing antibody or control IgG, Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice were infected with 2×106 yeasts intranasally. Lungs were harvested at days 3 and 7 post-infection to determine the number of CFUs. Data represent the mean ± SD (n=8–12 mice/group; representative of three experiments). F, Survival was recorded when mice were moribund. (n=9–12 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

While IL-4 is known to inhibit the immune response to H. capsulatum, elevation of this cytokine subsequent to the rise in fungal burden suggested that it was a consequence rather than a driver of the altered immune response in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice (43, 44). To determine the contribution of IL-4 to the phenotype of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice we administered mAb to this cytokine both prior to and during the course of infection. Since murine survival was unaltered in these mice, we concluded that IL-4 elevation was not responsible for the phenotype of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice (Supplemental Fig. 2A).

One concern in interpreting the elevation in cytokines in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice is that the higher fungal burden may have enhanced production. To test this assertion, we infected control animals with a one log higher inoculum of H. capsulatum; this number of yeasts replicated the fungal burden in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice (Fig. 2C). We measured cytokines in lung homogenates following instillation of the lower and higher number of yeast cells at 7 days post-infection. The exaggerated fungal burden in control mice increased IFN-γ and IL-1β cytokine production comparable to the amount in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice while TNF-α was unaltered (Fig. 2D). However, the quantity of IL-10 in the heavily infected controls did not differ from that of mice that received the lower inoculum (Fig. 2D). Thus, the high fungal burden was not the driving force in amplified IL-10 in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice. This finding demonstrates that the enhanced IL-10 production in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice is a consequence of HIF-1α deficiency while the heightened pathogen burden in these mice caused the increase in proinflammatory cytokines.

Since IL-10 was augmented early during infection, we examined its influence on the fungal burden and survival of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice. Anti-IL-10 mAb given to Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl and control mice reduced fungal burden compared to IgG control in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice and enhanced survival (Fig. 2E and 2F).

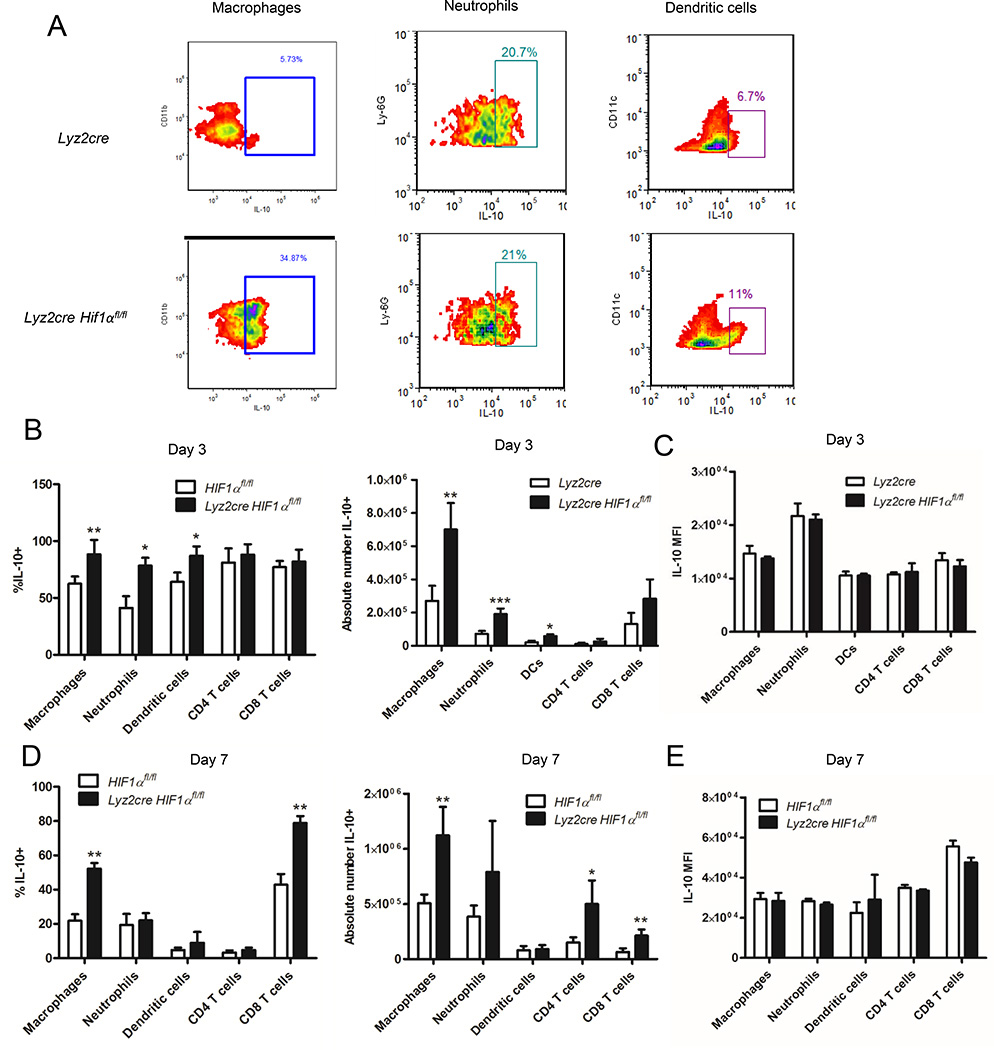

Mϕs are the primary IL-10 producing cells from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice following infection with H. capsulatum

We sought to determine the primary IL-10 producing cell populations within the lungs of infected mice. We innoculated control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice with H. capsulatum and performed intracellular IL-10 staining within several immune cell populations including Mϕs at days 3 and 7. Representative flow cytometry plots demonstrate IL-10 staining in myeloid cells at day 7 post-infection (Fig. 3A). Prior to infection, intracellular IL-10 is not detectable in control or Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice (data not shown). At day 3, multiple myeloid populations produced IL-10, but Mϕs constituted the majority of IL-10+ cells in both control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice (Fig. 3B). Likewise, at day 7, Mϕs still constituted the most numerous IL-10 producers in both groups (Fig. 3D). Relative to controls, the number of IL-10+ PMNs, DCs, and Mϕs isolated from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice at day 3 were increased, whereas at day 7 post-infection more IL-10+ lung Mϕs and T cells were present in the mutant mice (Fig. 3B and 3D). There was no change between the two groups in the IL-10 MFI in any of the cell populations at either day 3 or day 7 post-infection (Fig. 3C and 3E). Thus, Mϕ are the most numerous IL-10 producing cell population in response to H. capsulatum. The increase in IL-10 found in the lungs was most likely a consequence of more cells rather than inflated production at the single cell level since MFIs did not vary between identical cell populations from the two groups of mice.

FIGURE 3.

Mϕs from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice are a major source of IL-10 in response to H. capsulatum. Lung leukocytes were isolated from infected Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice at days 3 and 7 post-infection, stained for IL-10, and counted. A, Representative dot plots of IL-10 staining in Hif1αfl/fl and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl lung Mϕs, neutrophils, and dendritic cells at day 7 post-infection. B and D, Graphs represent the absolute number and % of IL-10+ cells in leukocyte populations at days 3 and 7 post-infection. C and E, Graphs represent the IL-10 MFI within those populations at those time points. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 6–8) from three experiments. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

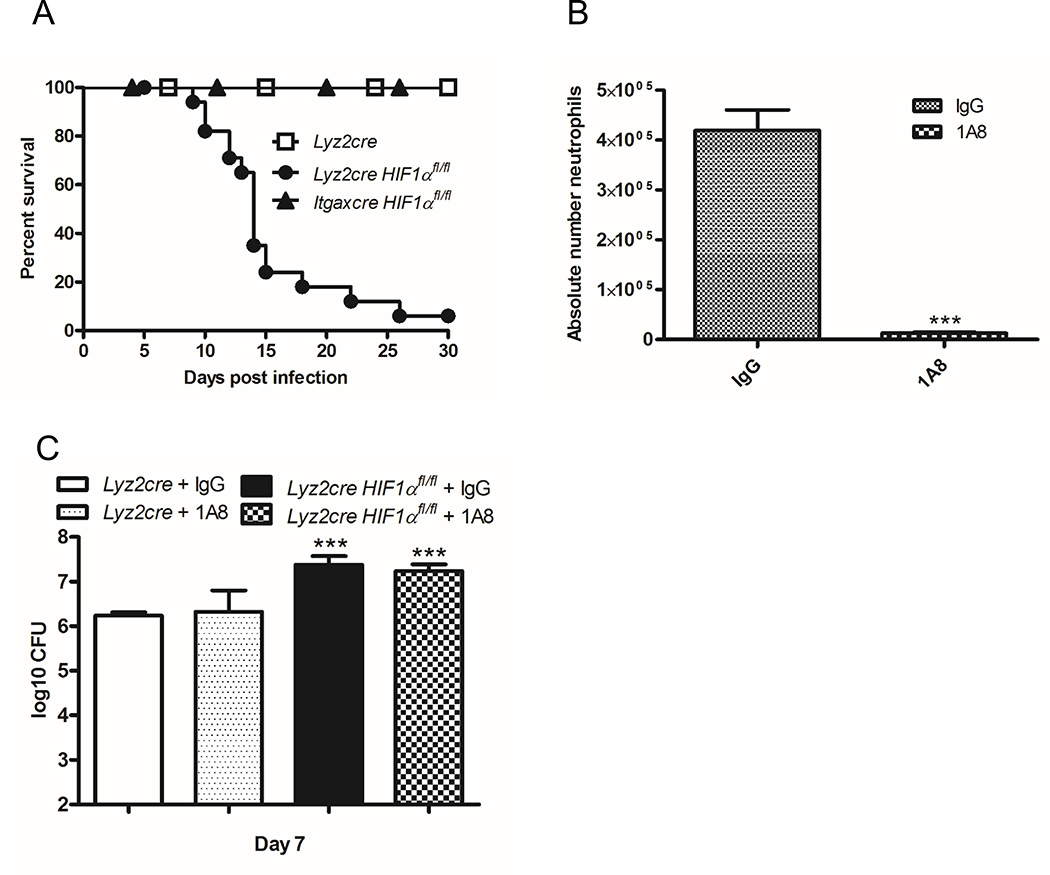

Loss of Mϕ HIF-1α is responsible for the survival defect in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice

Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice exhibit HIF-1α deletion in all myeloid cells. In order to hone in on the cell population(s) responsible for the survival defect within mutant mice, we generated Itgaxcre Hif1αfl/fl mice. In these mice HIF-1α is eliminated in alveolar Mϕs and tissue resident and monocyte-derived DCs (45). We infected control, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl, and Itgaxcre Hif1αfl/fl mice with a sublethal number of H. capsulatum yeast cells. As observed previously the vast majority of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice succumbed to infection while all control and Itgaxcre Hif1αfl/fl mice survived (Fig. 4A). These results suggested that HIF-1α in alveolar Mϕs and DCs was dispensable for survival following H. capsulatum infection. Thus, we can infer that the presence of this transcription factor in PMNs or Mϕs was required to confer protective immunity.

FIGURE 4.

HIF-1α expression in Mϕs, but not DCs, alveolar macrophages, or PMNs is required for murine survival during H. capsulatum infection. A, Lyz2cre, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl, and Itgaxcre Hif1αfl/fl mice were infected and survival recorded when mice were moribund. (n=10–18 mice/group; representative of five experiments) B, Absolute number of PMNs was determined at day 7 post-infection after depletion. PMNs were characterized as Ly6G+ CD11b+ CD11c−. (n=9 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) C, Lungs were harvested at day 7 post-infection to determine the number of CFUs. Data represent the mean ± SD. (n=9 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

We sought to directly address the impact of PMN HIF-1α. Studies that examine the necessity of PMNs in H. capsulatum by depleting them suggest that they are essential for protective immunity (46, 47). However, these reports utilize an antibody (clone RB6) that recognizes both Ly6G and Ly6C. Since the latter is expressed on PMNs and inflammatory monocytes, it is difficult to discriminate which of these populations is responsible for the aggressive infection in mice. We therefore sought to clarify the contribution of PMNs by depleting these cells in both wild type and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice with a Ly6G specific antibody. Following administration of 1A8 mAb or isotype control mAb, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl and wild type mice were infected for 7 days. The loss of PMNs was confirmed by differential lung leukocyte count (Fig. 4B). The lack of PMNs did not elevate the fungal burden in either control mice or Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice (Fig. 4C). Since PMNs were dispensable for fungal clearance, we concluded that these cells did not contribute to the phenotype observed in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice via either HIF-1α-dependent or independent mechanisms. These results demonstrate that Mϕ HIF-1α was required for murine survival. The importance of this population is consistent with our prior data that IL-10 contributes to the phenotype of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice and that Mϕ are the primary producer of IL-10 in these mice.

Infection with H. capsulatum drives HIF-1α transcription and protein nuclear localization within Mϕs

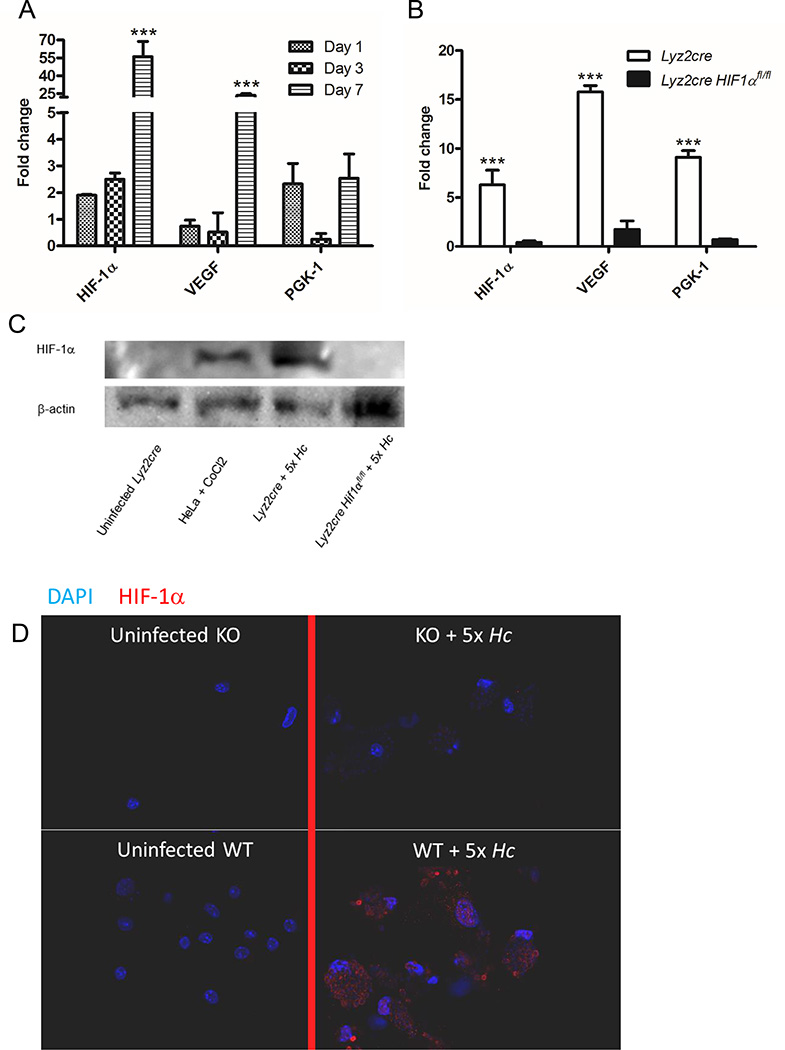

The accumulated data strongly implicated HIF-1α deficiency within Mϕs as the critical node for the elevated fungal burden and decreased survival in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice. To assess transcriptional induction of HIF-1α as well as several downstream targets including vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf-a) and phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (Pgk-1) in vivo, we infected animals with H. capsulatum expressing GFP and sorted infected pulmonary Mϕs (F4/80+ CD11b+ CD11c− GFP+ or GFP−) at 1, 3, and 7 days post-infection. Infected cells exhibited transcriptional upregulation of Hif-1α, Vegf-a, and Pgk-1 (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

H. capsulatum induces nuclear HIF-1α in Mϕs. A and B, mRNA expression of HIF-1α, VEGF, and PGK-1 was quantified by qRT-PCR relative to uninfected controls. A, GFP+ monocytes were collected at days 1, 3, and 7 following intranasal infection with GFP expressing yeast. (n=12 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) B, BMDMϕs were collected 24 h post-infection. (n=8 experiments/group) C, Immunoblot of HIF-1α and β-actin from whole-cell lysates of Mϕs infected with H. capsulatum for 24 h. (representative experiment of 3) D, Confocal images of BMDMϕs uninfected or infected for 24 h followed by nuclear staining (DAPI) and staining for HIF-1α. (representative experiment of 3) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

Evidence of other microbes driving HIF-1α led us to inquire whether H. capsulatum infection induces HIF-1α in the absence of hypoxia (8, 48–50). Accordingly, we infected control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs for 24 h and assessed the transcription of Hif-1α and its downstream targets; Hif-1α and Pgk-1 were induced over 5 fold while Vegf-a was induced over 10 fold in a HIF-1α dependent manner (Fig. 5B). We assessed expression of CD11b on Mϕ because it is the principal phagocytic receptor and it is regulated by HIF-1α: this integrin was not altered in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl cells in vitro or in vivo (51, 52) (Supplemental Fig. 3A and 3B).

To directly assess HIF-1α protein stabilization and cellular localization, we utilized uninfected cells or cells infected for 24 h from both control and HIF-1α-deficient BMDMϕs and analyzed protein expression and localization via western blot and confocal microscopy, respectively. Western blot analysis demonstrated HIF-1α protein in infected Lyz2cre cells, but no HIF-1α was detected in infected cells from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice (Fig. 5C). Confocal microscopic analysis demonstrated that HIF-1α was located within the nucleus following infection of wild type but not Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs with H. capsulatum (Fig. 5D). We concluded that H. capsulatum infection causes HIF-1α upregulation and translocation to the nucleus where it can modulate downstream targets.

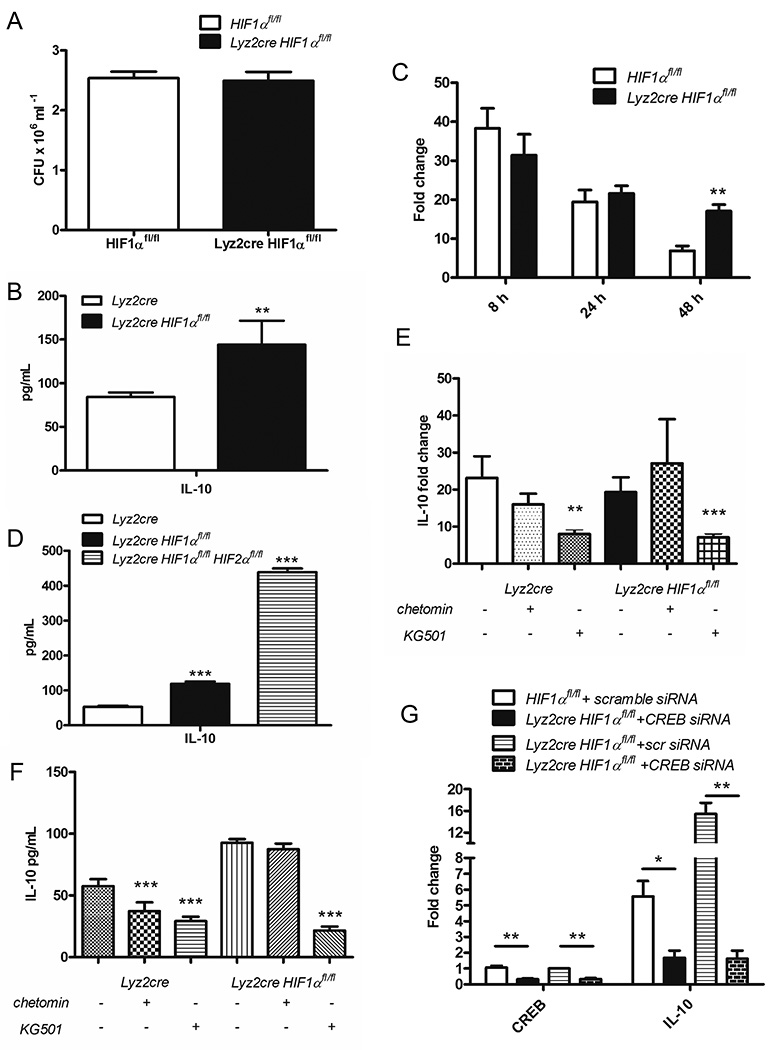

The transcription factor CREB, in the absence of HIF-1α, drives elevated IL-10 production in response to H. capsulatum infection

Since HIF-1α has been shown to positively regulate IL-10 production, the increase in this cytokine found in the lungs of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice was unexpected (53). To investigate the mechanism of IL-10 production, we infected control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs for 24 and 48 h. Fungal burdens at 48 h were not different between control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs (Fig. 6A). We quantified IL-10 in the cell culture supernatants; Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl derived Mϕs secreted nearly twice as much IL-10 only at 48 h (Fig. 6B). This elevation was associated with a concomitant enhancement in IL-10 transcription in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs compared to control (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

In the absence of HIF-1α, the transcription factor CREB drives elevated IL-10 production in response to H. capsulatum infection. A, BMDMϕs were infected for 48 h then lysed to determine fungal burden (n=4–6 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) B, D, F IL-10 concentration was determined in the cell culture supernatants by Magpix. C, E and G, mRNA expression of IL-10 was quantified by qRT-PCR relative to uninfected controls. B, BMDMϕs were infected for 48 h. (n=6 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) C, BMDMϕs were infected for 8, 24, or 48 h. (n=6–9 mice/group; representative of 5 experiments) D, Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl, and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl Hif2αfl/fl double knockout BMDMϕs were infected for 24 h. (n=6 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) E, F, BMDMϕs were infected for 48 h after treatment with DMOG (control), a HIF-1α-CBP interaction inhibitor (chetomin), or a CREB-CBP interaction inhibitor (KG-501). (n=9 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments). Treatment groups were compared to the DMOG control. F, BMDMϕs were infected for 48 h after treatment with scrambled siRNA (control) or CREB siRNA. (n=6 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

Competition between transcription factors for a limiting supply of CBP has been shown to regulate IL-10 production (54). Therefore we hypothesized that the absence of HIF-1α resulted in increased HIF-2α binding to CBP and subsequent elevation in IL-10 protein (55, 56). To test this postulate we infected BMDMϕs from controls, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice, and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl Hif1αfl/fl double knockout mice for 24 h and examined IL-10 protein in supernatants. The quantity of IL-10 in the absence of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α exceeded that of cells from control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice (Fig. 6D).

We then examined the function of CREB, another transcription factor known to bind CBP and drive IL-10 transcription (57). To test the contribution of CREB and HIF-1α on IL-10 production, we treated wild type BMDMϕs with small molecule inhibitors that prevent CREB (KG-501) or HIF-1α (chetomin) association with CBP. KG-501, but not chetomin, inhibited IL-10 transcription in response to H. capsulatum infection (Fig. 6E). KG-501 also decreased IL-10 protein during infection with H. capsulatum (Fig. 6F).

To address the concern of off-target effects of the inhibitor, we utilized siRNA to reduce CREB in both control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs. CREB knockdown reduced transcription of IL-10 in both control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs (Fig. 6G). These results demonstrate that CREB is important for IL-10 production in both control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs, but the presence of HIF-1α tempers IL-10 levels.

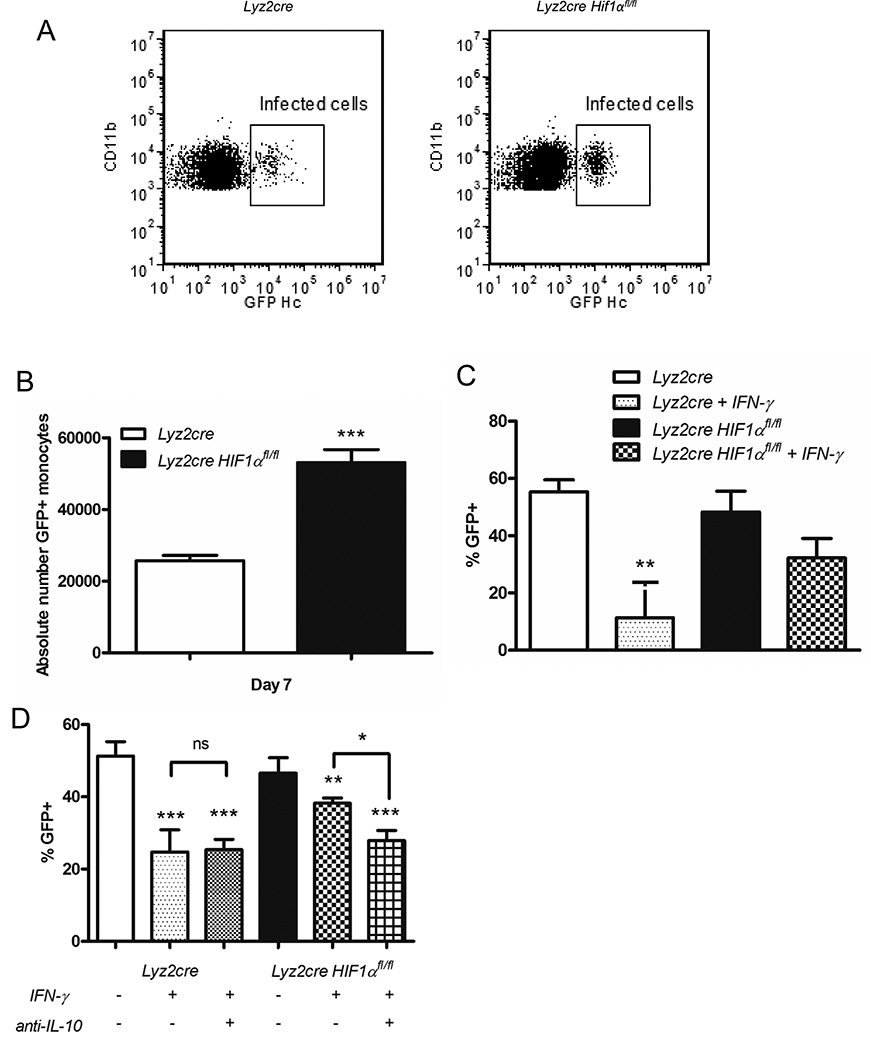

Elevated IL-10 production by Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs inhibits IFN-γ induced fungal control

Since Mϕs are the primary IL-10 producing cell and one of the primary sites of phagocytosis, we queried the number of these cells infected following administration of GFP+ H. capsulatum. There was an increase in infected cells from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice relative to controls with no alteration in GFP MFI within the infected cells (Figure 7A and 7B; data not shown). This finding implied that Mϕ from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice were more permissive for intracellular invasion that was not a consequence of altered expression of CD11b. Hence we asked if the Mϕ from the mutant mice were less responsive to an exogenous activating signal such as IFN-γ. IL-10 is known to inhibit the capacity of Mϕs to respond to IFN-γ (58). To address responsiveness of Mϕs to activating cytokine we infected wild type and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs with GFP+ H. capsulatum for up to 72 h with or without the addition of IFN-γ. While cytokine activation decreased the percentage of infected control BMDMϕs, this signal did not alter the infection of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs (Fig. 7C). Administration of anti-IL-10 at the time of infection enabled IFN-γ mediated activation of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs (Fig. 7D). Taken together our results suggest that elevated IL-10 from HIF-1α deficient-Mϕs inhibits IFN-γ responsiveness that is required for effective fungal clearance.

FIGURE 7.

IL-10 inhibits IFN-γ induced fungal control by Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs. GFP-expressing H. capsulatum was utilized to determine the infected populations in vivo (A, B) or in vitro (B, C). A, Representative flow cytometry plots of infected Mϕs at day 7 post-infection. B, Absolute number of infected Mϕs was determined at day 7 post-infection in Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice. (n=6 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) C and D, Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs were infected for 72 h with or without IFN-γ activation and IL-10 neutralization. Treatment groups were compared to the untreated control and to each other. (C, n=6 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments; D, n=6 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

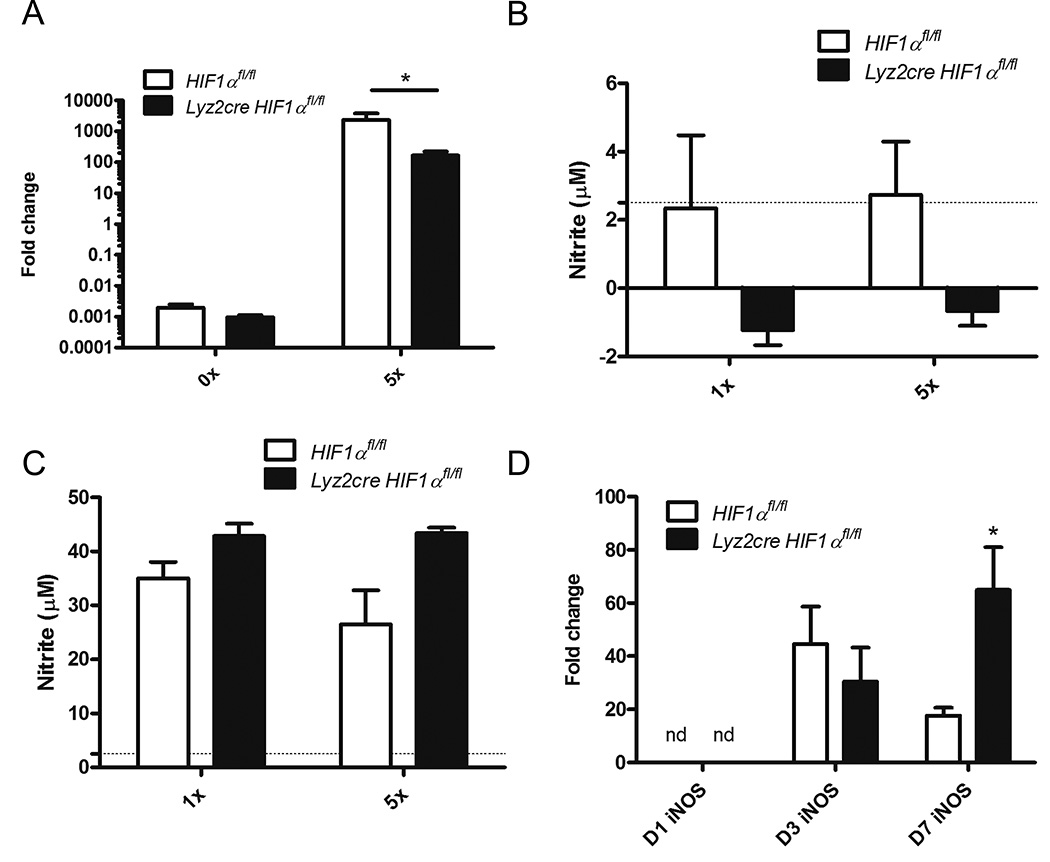

Profiles of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and NO in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice

HIF-1α evokes direct killing of many pathogenic microbes by primary mediators such as nitric oxide (22, 24). Decreased iNOS transcription and subsequently low nitric oxide levels have been implicated in diminished clearance of group A Streptococcus and Mycobacterium marinum in the setting of HIF-1α deficiency (22). Inhibition of iNOS in both of these models was able to elevate pathogen burden. To determine if NO was critically altered in HIF-1α deficiency, we first assessed the ability of H. capsulatum to evoke iNOS in bone marrow derived macrophages. Although infection led to iNOS induction in both control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl cells, it was significantly reduced in the absence of HIF-1α (Fig. 8A). However, NO production was not altered in the absence of HIF-1α (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

NO production is not diminished in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs infected with H. capsulatum. A, iNOS transcript was determined in Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs at 48 hours post-infection. (n=3 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) B and C, Lyz2cre and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs were infected for 48 h with or without IFN-γ activation. Supernatants were tested for nitrite. (B, n=3–8 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments; C, n=3 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) D, iNOS transcript was assessed in whole lung homogenates at 1, 3, and 7 days post-infection. (n=3–6 mice/group; representative of 3 experiments) nd = not detected; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Since IFN-γ activates murine macrophages to inhibit H. capsulatum growth through stimulation of nitric oxide generation, we activated and infected bone marrow derived macrophages (59, 60). Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl and control cells secreted similar quantities of nitrite (Fig. 8C).

Finally we examined iNOS induction in vivo. During early infection, iNOS was not detectable in whole lung homogenates (Fig. 8D). iNOS is elevated at day 3 post-infection in both Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl and control mice (Fig. 8D). By day 7 post-infection, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice express more iNOS than controls (Fig. 8D). These results suggest that diminished NO production in the absence of HIF-1α is not responsible for the elevated fungal burden and diminished survival of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that the transcription factor HIF-1α in the myeloid cell compartment was a central molecular regulator of the protective immune response to H. capsulatum. Its absence in these cells produced a progressive infection that led to the death of the vast majority of animals. The principal defect was not an alteration in the inflammatory response but rather an early and striking elevation in IL-10. Despite an abundance of cytokines known to enhance immunity, IL-10 overrode their impact on host resistance. Immunity was restored when this cytokine was neutralized by mAb to this cytokine. Since the exaggerated production of IL-10 was detected prior to the onset of an adaptive immune response to H. capsulatum, we surmised that its impact influenced innate immunity (61). The principal source of IL-10 was Mϕ thus localizing impaired immunity to this specific population. Two findings provided additional evidence that Mϕs were the cause of the collapse of immunity rather than another myeloid cell population. First, elimination of PMNs in both control and Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice did not alter fungal burden. Second, Itgaxcre Hif1αfl/fl mice which exhibit selective deletion in tissue and resident DCs and alveolar Mϕ survived the sublethal challenge. The unexpected elevation in IL-10 by HIF-1α-deficient Mϕ is not caused by HIF-2α but is largely driven by CREB. In vitro studies revealed that anti-IL-10 neutralization reversed the failure of Mϕ from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice to respond to IFN-γ-mediated activation.

While HIF-1α is classically described as a key element in the cell response to hypoxia, mounting evidence over the past decade has described its requirement in the immune response to several pathogens; often, HIF-1α is required for phagocyte activation and killing, but occasionally it is co-opted by the pathogen to promote intracellular survival (20, 25, 18, 62, 63). As a requisite factor for protective immunity exerted by Mϕ, HIF-1α has been shown to regulate production of cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial molecules (22, 24, 28, 39, 64, 65). Thus, in the context of infection, HIF-1α target genes within phagocytes and Mϕ in particular can be organized into two categories: one is production of soluble mediators that recruit and activate other populations of immune cells and two, regulation of microbicidal activity by cells exposed to pathogens.

Multiple pathogens are known to induce the transcription or stabilization of HIF-1α protein even in the absence of hypoxia (25, 18, 11, 66, 67, 19, 16). Accordingly, H. capsulatum-infected Mϕ promoted expression of HIF-1α protein as demonstrated by western blot. The robust transcriptional induction of HIF-1α protein leads to an elevation in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, which likely represents a massive accumulation with a delay prior to nuclear translocation. We confirmed the in vitro induction results with in vivo studies in which sorted lung M from wild-type mice transcribed the gene at day 7 post-infection, but not earlier. This finding does not correspond to the temporal identification of poor control of fungal burden in the mutant mice which begins on day 3. Although we could not detect by transcription a change in HIF-1α prior to day 7, clearly its impact precedes transcriptional upregulation. The likely explanation is that H. capsulatum stimulates protein stabilization prior to transcriptional induction.

We anticipated a role for myeloid HIF-1α in shaping the adaptive immune response to murine histoplasmosis since hypoxia is detected within liver granulomas induced by i.p. injection of yeast cells (2). However, protective immunity was subverted in the Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice prior to the onset of adaptive immunity. These data indicated that a maladaptive innate response led to the phenotype of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice.

To hone in on the innate immune cell population responsible for the defective immune response in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice, we evaluated the contribution of various myeloid lineage cells. Mϕs, alveolar Mϕs, PMNs, and resident DCs are important for phagocytosis of yeast cells following infection (51, 68, 69). These cells release cytokines and chemokines that facilitate mobilization of the inflammatory response to combat invasion by H. capsulatum. Since Itgaxcre Hif1αfl/fl mice did not manifest impaired survival we conclude that HIF-1α within DCs and alveolar Mϕs is dispensable following H. capsulatum infection. The fact that elimination of PMNs from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice did not alter fungal burden signifies that HIF-1α deficiency in this population was not a contributor to the failed protective immune response. Our data with PMN depletion contradicts prior studies whose results strongly suggest that PMNs are essential for H. capsulatum clearance (46, 47). However, those studies employed the antibody RB6 which is now known to recognize Ly-6G and Ly-6C. The latter is borne by inflammatory monocytes (70). Therefore it is quite likely that in those experiments both PMNs and inflammatory monocytes were depleted. The mAb that we employed, 1A8, is considered to be more selective for Ly-6G (70).

The pivotal contribution of HIF-1α in response to H. capsulatum was not to drive inflammatory cytokine production, but rather to temper IL-10. This finding is quite unexpected since HIF-1α binds to hypoxia response elements (HREs) that exist in the promoters for several cytokines and chemokines important in the myeloid response to H. capsulatum including TNF-α, CCL2, and IL-10 (71–73). The loss of HIF-1α did not reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine production or cell recruitment to the lungs following infection. In fact, there was an increase in several of these prototypically protective cytokines in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl lungs relative to control. These data contrast with infectious models in which decreased myeloid pro-inflammatory cytokine production is noted in the absence of HIF-1α; however, our data are congruent with a study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in mice where the lack of HIF-1α in myeloid cells does not diminish the generation of inflammatory cytokines (25, 18, 7). In our model of histoplasmosis, the fungal burden and not the absence of the transcription factor was responsible for the enhanced pro-inflammatory cytokine production observed in the Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice. The exception was IL-10; this cytokine was elevated in the lungs of the conditional knockouts independent of the fungal load. This result establishes that the loss of HIF-1α results in an early increase in IL-10, and this heightened response undermined the integrity of the innate immune response. A previous study by our group documented that the loss of IL-10 enhanced clearance of the fungus (33). However, the influence of this loss was not observed until adaptive immunity was operative. The current information clearly documents that early, exaggerated IL-10 can alter the function of Mϕ.

While several studies demonstrate that HIF-1α induces IL-10 transcription, here we established that deficiency of this transcription factor alone or in conjunction with HIF-2α deficiency actually elevates IL-10 transcript and protein production during H. capsulatum infection (53, 74). Although counterintuitive, there are several lines of evidence that support the notion that HIFs may moderate IL-10. First, inhibition of Hif-1α transcriptional induction in BMDMϕs enhances IL-10 transcript and secreted protein following infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (75). Second, LPS-challenged mice deficient in myeloid HIF-2α exhibit an elevation in circulating IL-10 (76). Taken together, these results indicate that the influence of HIFs on IL-10 may be context dependent.

One of the principal issues raised by our findings is how IL-10 dampened innate immunity. Mϕs must be activated by exogenous signals to exert anti-Histoplasma activity, and IFN-γ is central to the activation of Mϕ (77, 60). One known effect of IL-10 is that it blunts IFN-γ-induced activation of Mϕs thus thwarting the arming of these phagocytes to limit intracellular infection (58, 78). We asked if the heightened IL-10 in Mϕs from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice altered responsiveness to IFN-γ. Indeed, IFN-γ did not restrict fungal growth in these cells in vitro unless IL-10 was neutralized. In vivo, anti-IL-10 restored immunity as evidenced by a reduction in CFUs and an increase in survival. Although the bulk of IFN-γ is produced after day 5 largely by CD4+ T cells in an IL-12-dependent manner, there is an early production of this cytokine by unidentified sources (79). This initial generation appears to be important for early activation of Mϕs to limit intracellular growth.

In several infectious models, HIF-1α has been found to exert protection via induction of iNOS and subsequent generation of NO (22, 24). In fact IFN-γ-mediated macrophage activation leads to H. capsulatum growth inhibition through stimulation of nitric oxide generation (59, 60). However, we found that infection of Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl mice is associated with comparable iNOS transcript during early infection followed by an elevation during late infection. While these results were not anticipated, they are in agreement with previous studies that have demonstrated that IL-10 enhances macrophage NO generation in the presence of an activation signal (80, 81).

CREB was responsible for elevated IL-10 in the absence of HIF-1α. In order to drive gene transcription, HIF-1α directly interacts with the CBP/p300 complex which can then bind to target gene promoters (62). In addition to HIF-1α, CBP/p300 can interact with a wide variety of transcription factors; competition for a limiting quantity of CBP/p300 regulates transcriptional induction of HIF-1α targets (82, 83). We hypothesized that the lack of HIF-1α allowed other transcription factors to bind to CBP thus enhancing transcriptional induction of IL-10. One such factor is CREB, which is required for β-glucan-stimulated IL-10 in murine BMDMϕs (84). Our data indicate that CREB drives elevated IL-10 transcription in Mϕ in response to H. capsulatum; HIF-1α deficiency augmented CREB-mediated IL-10 production. While there are numerous binding sites on CBP, the contribution of other transcription factors to IL-10 production in the absence of HIF-1α is unlikely given that IL-10 protein is nearly lost with CREB inhibition or silencing. Our data suggests a novel mechanism of IL-10 regulation dependent on transcription factor competition for binding to CBP. In contrast to other models, HIF-1α is required to temper anti-inflammatory IL-10 production during the innate immune response to H. capsulatum infection. This finding is in accord with recent evidence that inhibition of HIF-1α elevates IL-10 secretion by LPS-treated BMDMϕs (75).

Although IL-10 transcriptional induction and protein secretion occurs at 24 h in our in vitro studies, Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl BMDMϕs only exhibit an increase relative to controls at 48 h. While the mechanism of this delay is unclear, several modes of IL-10 regulation may be responsible. The two most intriguing possibilities include control of IL-10 expression by microRNAs and HIF-1α-dependent regulation of mRNA stability. Both of these could account for the increase seen at both the transcriptional and resultant protein level. A variety of micro RNAs which are regulated by HIF-1α have been shown to inhibit IL-10 production; these include miR-27a and Let-7 family members Let-7b, Let-7c, and Let-7f (85–89). While few studies have focused on the role of HIF-1α in controlling mRNA stability, it binds to VEGF mRNA and regulates transcript decay (90, 91). One or both of these mechanisms may drive the differential expression of IL-10 in Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl versus control BMDMϕs.

Given the role of HIF-1α-dependent transcriptional regulation in vitro, the absence of an alteration of IL-10 MFI between cells from Lyz2cre Hif1αfl/fl and control mice was unexpected. Our inability to capture a change in IL-10 MFI in the presence of a dramatic increase in IL-10 may be the result of in vivo dynamics. The delayed transcript changes that are seen in vitro are observed in the absence of immigrating inflammatory cells. Moreover, infection in vitro is synchronized such that all cells are exposed simultaneously to the pathogen. The coordinated response does not occur in vivo since inflammatory cell recruitment is continuous and infection of these cells is asynchronous. This may obscure any changes in IL-10 within cells in the lung.

In summary, we identified HIF-1α as a vital transcription factor in the Mϕ response to H. capsulatum. HIF-1α was transcriptionally upregulated and protein stabilized in H. capsulatum-infected Mϕ exposed to normoxia. HIF-1α fortified the innate response to this fungus by tempering the production of IL-10 in Mϕ. One clinical ramification of our work is in the arena of the potential use of HIF inhibitors to treat malignancies (92). Based on our findings, this intervention may pose a risk for those exposed to H. capsulatum or perhaps other intracellular pathogens in which IL-10 is a prominent feature of their immune regulation. Thus, a cautious approach may be warranted in the deployment of HIF-1α inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathryn Wikenheiser-Brokamp, James Bridges, Joseph Qualls, Inga Kaufhold, and Victor Lescano for their valuable contributions. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the Research Flow Cytometry Core in the Division of Rheumatology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, supported in part by NIH AR-47363, NIH DK78392 and NIH DK90971.

Source of support: This work was supported by PHS grant AI-106292 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a grant-in-aid from the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, and T32 GM-063483.

Abbreviations used in this article

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia inducible factor-1α

- Mϕ

macrophage

- CBP

CREB-binding protein

- BMDMϕ

bone marrow derived macrophage

- DC

dendritic cell

- PMN

neutrophil

References

- 1.Chu JH, Feudtner C, Heydon K, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE. Hospitalizations for endemic mycoses: a population-based national study. Clin. Infect. Dis. An Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2006;42:822–825. doi: 10.1086/500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DuBois JC, Pasula R, Dade JE, Smulian AG. Yeast transcriptome and in vivo hypoxia detection reveals Histoplasma capsulatum response to low oxygen tension. Med. Mycol. 2015;54(1):40–58. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myv073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eric HL, Gu J, Schau M, Bunn HF. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is mediated by an O2-dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:7987–7992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A Conserved Family of Prolyl-4-Hydroxylases That Modify HIF. Science (80-.) 2001;294:1337–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cockman ME, Masson N, Mole DR, Jaakkola P, Chang G, Clifford SC, Maher ER, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell PH. Hypoxia Inducible Factor-α Binding and Ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau Tumor Suppressor Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:25733–25741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamura T, Sato S, Iwai K, Czyzyk-krzeska M, Conaway RC, Weliky J. Activation of HIF1α ubiquitination by a reconstituted von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97 doi: 10.1073/pnas.190332597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peyssonnaux C, Cejudo-Martin P, Doedens A, Zinkernagel AS, Johnson RS, Nizet V. Cutting edge: Essential role of hypoxia inducible factor-1α in development of lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis. J. Immunol. 2007;178:7516–7519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frede S, Stockmann C, Freitag P, Fandrey J. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induces HIF-1 activation in human monocytes via p44/42 MAPK and NF-kappaB. Biochem. J. 2006;396:517–527. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Johnson RS, Haddad GG, Karin M. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2008;453:807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blouin CC. Hypoxic gene activation by lipopolysaccharide in macrophages: implication of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Blood. 2003;103:1124–1130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rupp J, Gieffers J, Klinger M, van Zandbergen G, Wrase R, Maass M, Solbach W, Deiwick J, Hellwig-Burgel T. Chlamydia pneumoniae directly interferes with HIF-1alpha stabilization in human host cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:2181–2191. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang IIL, Watson IR, Der SD, Ohh M. Loss of VHL confers hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent resistance to vesicular stomatitis virus: role of HIF in antiviral response. J. Virol. 2006;80:10712–10723. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01014-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo Y-G, Na T-Y, Seo H-W, Seong JK, Park CK, Shin YK, Lee M-O. Hepatitis B virus X protein induces the expression of MTA1 and HDAC1, which enhances hypoxia signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:3405–3413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson GK, Brimacombe CL, Rowe IA, Reynolds GM, Fletcher NF, Stamataki Z, Bhogal RH, Simões ML, Ashcroft M, Afford SC, Mitry RR, Dhawan A, Mee CJ, Hübscher SG, Balfe P, McKeating JA. A dual role for hypoxia inducible factor-1α in the hepatitis C virus lifecycle and hepatoma migration. J. Hepatol. 2012;56:803–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu ZH, Wright JD, Belt B, Cardiff RD, Arbeit JM. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 facilitates cervical cancer progression in human papillomavirus type 16 transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:667–681. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiley M, Sweeney KR, Chan Da, Brown KM, McMurtrey C, Howard EW, Giaccia AJ, Blader IJ. Toxoplasma gondii activates hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) by stabilizing the HIF-1α subunit via type I activin-like receptor kinase receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:26852–26860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degrossoli a, Arrais-Silva WW, Colhone MC, Gadelha FR, Joazeiro PP, Giorgio S. The Influence of Low Oxygen on Macrophage Response to Leishmania Infection. Scand. J. Immunol. 2011;74:165–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shepardson KM, Jhingran A, Caffrey A, Obar JJ, Suratt BT, Berwin BL, Hohl TM, Cramer Ra. Myeloid derived hypoxia inducible factor 1-α is required for protection against pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004378. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werth N, Beerlage C, Rosenberger C, Yazdi AS, Edelmann M, Amr A, Bernhardt W, von Eiff C, Becker K, Schäfer A, Peschel A, Kempf VaJ. Activation of hypoxia inducible factor 1 is a general phenomenon in infections with human pathogens. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nizet V, Johnson RS. Interdependence of hypoxic and innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:609–617. doi: 10.1038/nri2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zarember KA, Malech HL. HIF-1α: A master regulator of innate host defenses? J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1702–1704. doi: 10.1172/JCI25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peyssonnaux C, Datta V, Cramer T, Doedens A, Theodorakis EA, Gallo RL, Hurtado-Ziola N, Nizet V, Johnson RS. HIF-1alpha expression regulates the bactericidal capacity of phagocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1806–1815. doi: 10.1172/JCI23865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinkernagel AS, Peyssonnaux C, Johnson RS, Nizet V. Pharmacologic augmentation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α with mimosine boosts the bactericidal capacity of phagocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;197:214–217. doi: 10.1086/524843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elks PM, Brizee S, van der Vaart M, Walmsley SR, van Eeden FJ, Renshaw Sa, Meijer AH. Hypoxia inducible factor signaling modulates susceptibility to mycobacterial infection via a nitric oxide dependent mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003789. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger Ea, McClellan Sa, Vistisen KS, Hazlett LD. HIF-1α is essential for effective PMN bacterial killing, antimicrobial peptide production and apoptosis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003457. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López Campos GN, Velarde Félix JS, Sandoval Ramírez L, Cázares Salazar S, Corona Nakamura aL, Amaya Tapia G, Prado Montes de Oca E. Polymorphism in cathelicidin gene (CAMP) that alters Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α::ARNT) binding is not associated with tuberculosis. Int. J. Immunogenet. 2014;41:54–62. doi: 10.1111/iji.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nizet V, Ohtake T, Lauth X, Trowbridge J, Rudisill J, Dorschner Ra, Pestonjamasp V, Piraino J, Huttner K, Gallo RL. Innate antimicrobial peptide protects the skin from invasive bacterial infection. Nature. 2001;414:454–457. doi: 10.1038/35106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu G, Tang Y, Geng N, Zheng M, Jiang J, Li L, Li K, Lei Z, Chen W, Fan Y, Ma X, Li L, Wang X, Liang X. HIF-α/MIF and NF-κB/IL-6 axes contribute to the recruitment of CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells in hypoxic microenvironment of HNSCC. Neoplasia. 2014;16 doi: 10.1593/neo.132034. 168–IN21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schödel J, Oikonomopoulos S, Ragoussis J, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Mole DR. High-Resolution Genome-Wide Mapping of HIF-Binding Sites by ChIP-Seq. Blood. 2011;117:e207–e217. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5771–5777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redford PS, Murray PJ, O’Garra A. The role of IL-10 in immune regulation during M. tuberculosis infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:261–270. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George S, Deepe J, Gibbons RS. Protective and memory immunity to Histoplasma capsulatum in the absence of IL-10. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5353–5362. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brummer E, Kurita N, Yoshida S, Nishimura K, Miyaji M. Killing of Histoplasma capsulatum by γ-interferon-activated human monocyte-derived macrophages: Evidence for a superoxide anion-dependent mechanism. J. Med. Microbiol. 1991;35:29–34. doi: 10.1099/00222615-35-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng JK, Lin S, Kung JT, Finkelman FD, Wu-Hsieh BA. The combined effect of IL-4 and IL-10 suppresses the generation of, but does not change the polarity of, type-1 T cells in Histoplasma infection. Int. Immunol. 2005;17:193–205. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allendoerfer R, Deepe GS. Intrapulmonary response to Histoplasma capsulatum in gamma interferon knockout mice. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:2564–2569. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2564-2569.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deepe GS, Gibbons RS, Smulian AG. Histoplasma capsulatum manifests preferential invasion of phagocytic subpopulations in murine lungs. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;84:669–678. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0308154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cramer T, Yamanishi Y, Clausen BE, Förster I, Pawlinski R, Mackman N, Haase VH, Jaenisch R, Corr M, Nizet V, Firestein GS, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Johnson RS. HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 2003;112:645–657. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinkernagel AS, Johnson RS, Nizet V. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) function in innate immunity and infection. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2007;85:1339–1346. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stowe AM, Wacker BK, Cravens PD, Perfater JL, Li MK, Hu R, Freie AB, Stüve O, Gidday JM. CCL2 upregulation triggers hypoxic preconditioning-induced protection from stroke. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clemons VK, Darbonne WC, Curnutte JT, Sobel RA, Stevens DA. Experimental histoplasmosis in mice treated with anti-murine interferon-gamma antibody and in interferon-gamma gene knockout mice. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:997–1001. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deepe GS, McGuinness M. Interleukin-1 and host control of pulmonary histoplasmosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:855–864. doi: 10.1086/506946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gildea LA, Gibbons R, Finkelman FD, Deepe GS. Overexpression of interleukin-4 in lungs of mice impairs elimination of Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3787–3793. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3787-3793.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szymczak WA, Deepe GS. The CCL7-CCL2-CCR2 axis regulates IL-4 production in lungs and fungal immunity. J. Immunol. 2009;183:1964–1974. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caton ML, Smith-Raska MR, Reizis B. Notch-RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8- dendritic cells in the spleen. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1653–1664. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sá-Nunes A, Medeiros AI, Sorgi CA, Soares EG, Maffei CML, Silva CL, Faccioli LH. Gr-1+ cells play an essential role in an experimental model of disseminated histoplasmosis. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1393–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou P, Miller G, Seder RA. Factors involved in regulating primary and secondary immunity to infection with Histoplasma capsulatum: TNF-α plays a critical role in maintaining secondary immunity in the absence of IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 1998;160:1359–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peyssonnaux C, Zinkernagel AS, Schuepbach RA, Rankin E, Vaulont S, Haase VH, Nizet V, Johnson RS. Regulation of iron homeostasis by the hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs) J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1926–1932. doi: 10.1172/JCI31370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu F, Mu R, Zhu J, Shi L, Li Y, Liu X, Shao W, Li G, Li M, Su Y, Cohen PL, Qiu X, Li Z. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α provoke toll-like receptor signalling-induced inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng S-C, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Martens JHA, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, Manjeri GR, Li Y, Ifrim DC, Arts RJW, van der Veer BMJW, Deen PMT, Logie C, O’Neill LA, Willems P, van de Veerdonk FL, van der Meer JWM, Ng A, Joosten LAB, Wijmenga C, Stunnenberg HG, Xavier RJ, Netea MG. mTOR- and HIF-1α-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science (80-.) 2014;345:1250684–1250684. doi: 10.1126/science.1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newman SL, Bucher C, Rhodes J, Bullock WE. Phagocytosis of Histoplasma capsulatum yeasts and microconidia by human cultured macrophages and alveolar macrophages. Cellular cytoskeleton requirement for attachment and ingestion. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:223–230. doi: 10.1172/JCI114416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kong T, Eltzschig HK, Karhausen J, Colgan SP, Shelley CS. Leukocyte adhesion during hypoxia is mediated by HIF-1-dependent induction of β2 integrin gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:10440–10445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401339101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cai Z, Luo W, Zhan H, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is required for remote ischemic preconditioning of the heart. Pnas. 2013;110:17462–17467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317158110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alvarez Y, Municio C, Alonso S, Sánchez Crespo M, Fernández N. The induction of IL-10 by zymosan in dendritic cells depends on CREB activation by the coactivators CREB-binding protein and TORC2 and autocrine PGE2. J. Immunol. 2009;183:1471–1479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vo N, Goodman RH. CREB-binding protein and p300 in transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:13505–13508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin M, Rehani K, Jope RS, Michalek SM. Toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine production is differentially regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:777–784. doi: 10.1038/ni1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanin DE, Prendergast CT, Mountford aP. IL-10 production in macrophages is regulated by a TLR-driven CREB-mediated mechanism that is linked to genes involved in cell metabolism. J. Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cunha FQ, Mohcada S, Liew FY. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) inhibits the induction of nitric oxide synthase by interferon-γ in murine macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;182:1155–1159. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91852-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lane TE, Otero GC, Wu-Hsieh BA, Howard DH. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase by stimulated macrophages correlates with their antihistoplasma activity. Infect. Immun. 1994;62:1478–1479. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1478-1479.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakamura LT, Wu-Hsieh BA, Howard DH. Recombinant murine gamma interferon stimulates macrophages of the RAW cell line to inhibit intracellular growth of Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect. Immun. 1994;62:680–684. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.680-684.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cain JA, Deepe GSJ. Evolution of the primary immune response to Histoplasma capsulatum in murine lung. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1473–1481. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1473-1481.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee J-W, Bae S-H, Jeong J-W, Kim S-H, Kim K-W. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1)α: its protein stability and biological functions. Exp. Mol. Med. 2004;36:1–12. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matak P, Heinis M, Mathieu JRR, Corriden R, Cuvellier S, Delga S, Mounier R, Rouquette A, Raymond J, Lamarque D, Emile J-F, Nizet V, Touati E, Peyssonnaux C. Myeloid HIF-1 is protective in Helicobacter pylori-mediated gastritis. J. Immunol. 2015;194:3259–3266. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walmsley SR, Cadwallader KA, Chilvers ER. The role of HIF-1α in myeloid cell inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:434–439. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imtiyaz HZ, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors as essential regulators of inflammation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010;345:105–120. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hartmann H, Eltzschig HK, Wurz H, Hantke K, Rakin A, Yazdi AS, Matteoli G, Bohn E, Autenrieth IB, Karhausen J, Neumann D, Colgan SP, Kempf VAJ. Hypoxia-independent activation of HIF-1 by enterobacteriaceae and their siderophores. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:756–767. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh AK, Mukhopadhyay C, Biswas S, Singh VK, Mukhopadhyay CK. Intracellular pathogen Leishmania donovani activates hypoxia inducible factor-1 by dual mechanism for survival advantage within macrophage. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brummer E, Kurita N, Yosihida S, Nishimura K, Miyaji M. Fungistatic activity of human neutrophils against Histoplasma capsulatum: correlation with phagocytosis. J. Infect. Dis. 1991;164:158–162. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gildea La, Morris RE, Newman SL. Histoplasma capsulatum yeasts are phagocytosed via very late antigen-5, killed, and processed for antigen presentation by human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1049–1056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Daley JM, Thomay Aa, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Andreou K, Rajendran R, Krstic-Demonacos M, Demonacos C. Regulation of CXCR4 gene expression in breast cancer cells under diverse stress conditions. Int. J. Oncol. 2012;41:2253–2259. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Acosta-Iborra B, Elorza A, Olazabal IM, Martín-Cofreces NB, Martin-Puig S, Miró M, Calzada MJ, Aragonés J, Sánchez-Madrid F, Landázuri MO. Macrophage oxygen sensing modulates antigen presentation and phagocytic functions involving IFN-γ production through the HIF-1α transcription factor. J. Immunol. 2009;182:3155–3164. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baay-Guzman GJ, Bebenek IG, Zeidler M, Hernandez-Pando R, Vega MI, Garcia-Zepeda Ea, Antonio-Andres G, Bonavida B, Riedl M, Kleerup E, Tashkin DP, Hankinson O, Huerta-Yepez S. HIF-1 expression is associated with CCL2 chemokine expression in airway inflammatory cells: implications in allergic airway inflammation. Respir. Res. 2012;13:60. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Lewis CE. Hypoxia regulates macrophage functions in inflammation. J. Immunol. 2005;175:6257–6263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palsson-McDermott EM, Curtis AM, Goel G, Lauterbach MAR, Sheedy FJ, Gleeson LE, van den Bosch MWM, Quinn SR, Domingo-Fernandez R, Johnson DGW, Jiang J, Israelsen WJ, Keane J, Thomas C, Clish C, Vanden Heiden M, Xavier RJ, O’Neill LAJ. Pyruvate Kinase M2 regulates Hif-1α activity and IL-1β induction and is a critical determinant of the Warburg effect in LPS-activated macrophages. Cell Metab. 2015;21:65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Imtiyaz HZ, Williams EP, Hickey MM, Patel SA, Durham AC, Yuan L, Hammond R, Gimotty PA, Keith B, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2α regulates macrophage function in mouse models of acute and tumor inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:2699–2714. doi: 10.1172/JCI39506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu-Hsieh BA, Howard DH. Inhibition of the intracellular growth of Histoplasma capsulatum by recombinant murine gamma interferon. Infect. Immun. 1987;55:1014–1016. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.1014-1016.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oswald IP, Wynn TA, Sher A, James SL. Interleukin 10 inhibits macrophage microbicidal activity by blocking the endogenous production of tumor necrosis factor-α required as a costimulatory factor for interferon γ-induced activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:8676–8680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou P, Sieve MC, Bennett J, Kwon-Chung KJ, Tewari RP, Gazzinelli RT, Sher A, Seder RA. IL-12 prevents mortality in mice infected with Histoplasma capsulatum through induction of IFN-gamma. J. Immunol. 1995;155:785–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maru A, Jackson SK. Opposite effects of interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 on nitric oxide production in murine macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 1996;5:110–112. doi: 10.1155/S096293519600018X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jacobs F, Chaussabel D, Truyens C, Leclerq V, Carlier Y, Goldman M, Vray B. IL-10 up-regulates nitric oxide (NO) synthesis by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated macrophages: Improved control of Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998;113:59–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yin Z, Haynie J, Yang X, Han B, Kiatchoosakun S, Restivo J, Yuan S, Prabhakar NR, Herrup K, Conlon Ra, Hoit BD, Watanabe M, Yang Y-C. The essential role of Cited2, a negative regulator for HIF-1α, in heart development and neurulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:10488–10493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162371799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodríguez-Jiménez FJ, Moreno-Manzano V. Modulation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) from an integrative pharmacological perspective. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. C. 2012;69:519–534. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0813-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Elcombe SE, Naqvi S, Van Den Bosch MWM, MacKenzie KF, Cianfanelli F, Brown GD, Arthur JSC. Dectin-1 regulates IL-10 production via a MSK1/2 and CREB dependent pathway and promotes the induction of regulatory macrophage markers. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhao Q, Li Y, Tan BB, Fan LQ, Yang PG, Tian Y. HIF-1α induces multidrug resistance in gastric cancer cells by inducing miR-27a. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kulshreshtha R, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, Garzon R, Alder H, Agosto-Perez FJ, Davuluri R, Liu C-G, Croce CM, Negrini M, Calin GA, Ivan M. A MicroRNA Signature of Hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;27:1859–1867. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01395-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xie N, Cui H, Banerjee S, Tan Z, Salomao R, Fu M, Abraham E, Thannickal VJ, Liu G. miR-27a regulates inflammatory response of macrophages by targeting IL-10. J. Immunol. 2014;193:327–334. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen Z, Lai TC, Jan YH, Lin FM, Wang WC, Xiao H, Wang YT, Sun W, Cui X, Li YS, Fang T, Zhao H, Padmanabhan C, Sun R, Wang DL, Jin H, Chau GY, Da Huang H, Hsiao M, Shyy JYJ. Hypoxia-responsive miRNAs target argonaute 1 to promote angiogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:1057–1067. doi: 10.1172/JCI65344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Swaminathan S, Suzuki K, Seddiki N, Kaplan W, Cowley MJ, Hood CL, Clancy JL, Murray DD, Méndez C, Gelgor L, Anderson B, Roth N, Cooper Da, Kelleher AD. Differential regulation of the Let-7 family of microRNAs in CD4+ T cells alters IL-10 expression. J. Immunol. 2012;188:6238–6246. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]