Abstract

Hypoparathyroidism is a disease of chronic hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia due to a deficiency of parathyroid hormone (PTH). PTH and analogs of the hormone are of interest as potential therapies. Accordingly, we examined the pharmacological properties of a long-acting PTH analog, [Ala1,3,12,18,22, Gln10,Arg11,Trp14,Lys26]-PTH(1–14)/PTHrP(15–36) (LA–PTH) in thyroparathyroidectomized (TPTX) rats, a model of HP, as well as in normal monkeys. In TPTX rats, a single intra-venous administration of LA-PTH at a dose of 0.9 nmol/kg increased serum calcium (sCa) and decreased serum phosphate (sPi) to near-normal levels for longer than 48 hours, while PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84), each injected at a dose 80-fold higher than that used for LA-PTH, increased sCa and decreased sPi only modestly and transiently (< 6 hours). LA-PTH also exhibited enhanced and prolonged efficacy versus PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84) for elevating sCa when administered subcutaneously (SC) into monkeys. Daily SC administration of LA-PTH (1.8 nmol/kg) into TPTX rats for 28-days elevated sCa to near normal levels without causing hypercalciuria or increasing bone resorption markers, a desirable goal in the treatment of hypoparathyroidism. The results are supportive of further study of long-acting PTH analogs as potential therapies for patients with hypoparathyroidism.

Keywords: Hypoparathyroidism, Long-acting PTH Analog, PTH Receptor, Hormone Replacement Therapy, Thyroparathyroidectomized Rats, Calcium Homeostasis

Introduction

Hypoparathyroidism (HP) is a rare disorder of calcium and phosphate metabolism that most often arises as a result of parathyroid gland damage or removal during surgery of the thyroid gland, but is also associated with hereditary or acquired abnormalities, such as autoimmunity, Di George syndrome, mitochondrial dysfunction, and activating mutations of the calcium-sensing receptor(1,2). HP is unusual among endocrine disorders in that it is not treated, until recently, by replacement with the missing hormone. Conventional therapy for HP involves large doses of vitamin D (usually 1,25(OH)2Vitamin-D3, the active form) and oral calcium supplementation, which, although often effective, is associated with marked swings in blood Ca (hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia), hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis(3,4). Recently, several clinical investigations have explored the use of PTH(1–84) or the N-terminal PTH fragment, PTH(1–34), as potential therapies for HP, and the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase 3 study on PTH(1–84) have culminated in the approval of this ligand, administered via once-daily via subcutaneous injection as a new line of therapy(5–9). While this represents an important advance in the treatment of the disease, certain challenges persist, particularly in the capacity to maintain a steady-state level of blood calcium without excessive urinary calcium excretion.

Part of the success of the treatment with PTH(1–84) appears to be due to a considerably prolonged pharmacokinetic profile exhibited by the peptide when administered SC into the thigh in humans, as serum half-life times were found to be two to three hours(8). The true serum half-life of PTH(1–84) in humans is quite short, a matter of minutes, as demonstrated by studies on the rate of clearance of the hormone from blood after removal of hyper-functioning parathyroid glands in patients with parathyroid adenomas(10). The mechanism of the slower absorption rate of PTH(1–84) when administered subcutaneously has not been explained but is useful in the application to HP, as it translates into extended elevations in serum calcium. A study on the pharmacodynamic profile of PTH(1–84) in HP patients thus found that sCa levels increased for many hours after a single SC injection, with peak levels occurring some 7 hours post-administration(8). Mean serum Ca levels, however, returned to pre-dose, hypocalcemic levels by 24 hours, and hypercalcemia was observed at peak times in 71% of the PTH(1–84)-injected subjects, prompting the suggestion that more effective treatment might be achieved with a lower dose administered twice- or three times daily(8). Other studies have shown that delivery of PTH(1–34) by infusion pump can control sCa levels in HP patients more effectively than twice-daily injection(11,12).

Recent structure-activity studies have identified PTH analogs that exhibit markedly prolonged cAMP signaling actions in PTHR1-expressing cells, as well as prolonged functional responses in animals(13,14). These analogs emerged from efforts initially aimed at optimizing the N-terminal pharmacophoric region of PTH(1–34)(15,16) and which culminated in the joining of the optimized N-terminal PTH(1–14) sequence to a C-terminal segment derived from the (15–36) region of PTHrP(14). The prolonged signaling action of these analogs appears to involve a mechanism of pseudo-irreversible binding to a distinct PTH receptor (PTHR1) conformation (R0), which maintains high affinity for the ligand through multiple rounds of G protein coupling(17). Moreover, sub-cellular tracking studies in transfected HEK-293 cells have suggested that prolonged signaling involves functional complexes located within internalized endosomal vesicles(18–20).

When injected SC into mice, the modified PTH analogs induce calcemic and hypophosphatemic responses that persist for many hours(13,14) yet the peptides disappear from the blood within several minutes. This strong dissociation between pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties suggests that the analogs are cleared rapidly from the circulation, in part by binding efficiently and stably to PTH receptors in target cells, in which they mediate extended downstream functional responses. The purpose of the current study is to explore the pharmacologic actions of one of these long-acting analogs, [Ala1,3,12,18,22, Gln10,Arg11,Trp14,Lys26]-PTH(1–14)/PTHrP(15–36) (LA–PTH), in thyroparathyroidectomized (TPTX) rats, an animal model of hypoparathyroidism, as well as in normal monkeys.

Materials & Methods

Peptides

All peptides used were based on the human PTH or PTHrP amino acid peptide sequence, except for the PTH(1–34) analog used for radiolabeling, which was based on the rat PTH sequence. Specific analogs assessed for function were: PTH(1–34); PTH(1–84), LA-PTH ([Ala1,3,12,Gln10,Arg11,Trp14]PTH(1–14)/[Ala18,22,Lys26]PTHrP(15–36)COOH) and M-PTH(1–15) ([Ala1,12,Aib3,Nle8,Gln10,Har11,Trp14,Tyr15]-PTH(1–15)NH2), in which Aib is alpha-aminoisobutyric acid, Har is homoarginine and Nle is norleucine. Radioligands used were 125I-PTH(1–34) (125I-[Nle8,21,Tyr34]-ratPTH(1–34)NH2) and 125I-M-PTH(1–15) and were prepared by chloramine-T-based radioiodination followed by reversed-phase HPLC purification. Peptides were prepared by conventional chemical synthesis except PTH(1–84) which was produced recombinantly(21). Peptide purity was confirmed to be greater than 95 % by reverse-phase HPLC.

In vitro characterization

Cell culture

GP-2.3 cells, an HEK-293-derived cell line that stably expresses the luciferase-based pGlosensor-22F (Glosensor) cAMP reporter plasmid (Promega Corp. USA) along with the human PTHR1(18), were cultured in DMEM supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%). Cells were seeded into 10 cm dishes for membrane preparations, or into 96-well plates for glosensor cAMP assays, and used for assay two to four days after the monolayer became confluent.

Competition binding assays

Ligand binding to the PTHR1 in R0 and RG conformations were assessed by competition methods using membranes prepared from GP-2.3 cells and either 125I-PTH(1–34) (R0) or 125I-M-PTH(1–15) (RG) as tracer radioligand and GTPγS (1×10−5 M) included in the R0 assays(17). Binding reactions were performed in 96-well vacuum filtration plates and were incubated at room temperature for 90 minutes; the plates were then processed by vacuum filtration, and after washing, the filters were removed and counted for gamma irradiation. Nonspecific binding was determined in reactions containing an excess (5×10−7 M) of unlabeled PTH(1–34). Curves were fit to the data using a four-parameter sigmoidal dose-response equation.

cAMP signaling assays

Ligand effects on PTHR1 mediated cAMP signaling were assessed via the (Glosensor) cAMP reporter expressed in GP-2.3 cells. The intact cells in 96-well plates were pre-loaded with luciferin for 20 minutes at room temperature, then treated with a test ligand and placed into a PerkinElmer Envision plate reader for an additional 60 minutes, during which time the development of cAMP-dependent luminescence was measured at two-minute intervals. Ligand dose-response curves were generated by plotting the peak luminescence signal obtained at each dose (typically occurring 10–15 minutes after ligand addition) versus ligand concentration. Curves were fit to the data using a four-parameter sigmoidal dose-response equation.

In vivo pharmacology

TPTX-rats

Surgical thyroparathyroidectomy (TPTX) was performed on six-week old rats obtained from Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc. After surgery, pellet food (CE-2; CLEA Japan, Inc.) containing 1.10 % calcium and 1.09% phosphate moisturized with tap water was supplied inside each cage for easy access and digestion in sham-operated and TPTX rats. Post-surgical rats exhibiting sCa levels less than 8.0 mg/dL at 5 days after TPTX-surgery were selected for subsequent peptide injection studies from the next day. Peptides were diluted in phosphate-citrate-buffered saline vehicle (prepared by adding 23 mmol/L citric acid/100 mmol/L NaCl to 25 mmol/L sodium-phosphate/ 100 mmol/L NaCl until the pH of 5.0 was attained) containing 0.05 % Tween-80 (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.). TPTX rats were injected IV or SC with vehicle or vehicle containing a PTH peptide. Blood samples were obtained from the jugular vein immediately before and at times after injection. 24-hour urine samples were collected in metabolic cages.

For pharmacokinetic studies, plasma samples were prepared in the presence of protease inhibitors (aprotinin, leupeptin, EDTA). Plasma levels of PTH(1–84) were assessed by ELISA assay (Human BioActive PTH(1–84) ELISA kit, Immutopics Inc.), and plasma levels of PTH(1–34) and LA-PTH were assessed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Serum half-life (t1/2) values were calculated by non-compartment methods using WinNonlin (Pharsight).

Serum and urinary calcium (sCa and uCa), phosphorus (sPi and uPi), and urinary creatinine (uCre) concentrations were measured with an automatic analyzer (7180, Hitachi, Ltd.). Urinary C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTx) was measured using a RatLaps ELISA kit (Immunodiagnostic System Ltd.), and the data were normalized to the uCre concentrations. Serum procollagen I N-terminal propeptide (PINP) levels were measured using a Rat/Mouse PINP EIA (Immunodiagnostic System Ltd.). Serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D3] levels were determined by a radioimmunoassay (Immunodiagnostic System Ltd.).

Femurs, tibia and lumbar vertebrae (L2–4) were isolated, and BMD of the vertebrae and right femurs was assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) using a DCS-600EX (Aloka) bone densitometer. Micro X-ray CT imaging was carried out using the R_mCT2 system (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) and structural parameters were analyzed using a TRI/3D-BON (Ratoc System Engineering Co., Tokyo, Japan) in accordance with the guidelines described in Bouxsein and colleagues(22). Trabecular bone microarchitecture of 100 CT slices (4000-µm area) starting at 800 µm below the outer edge of the growth plate with a voxel size of 40 µm using 90 Kv and 160 µA were assessed. Cortical bone geometry of 100 CT slices (2000-µm area) in the center of femoral midshaft with a voxel size of 20 µm using 90 Kv and 160 µA were also assessed.

Monkeys

Male cynomolgus monkeys at age 3 to 4 years were purchased from Hamri Co. Ltd (Tokyo, Japan).

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chugai Pharmaceutical, and were conducted in accordance with the approved protocols and the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at Chugai. Chugai Pharmaceutical is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as the mean ± standard error (SE) and statistical significance was determined using SAS (Ver.5.00., SAS Institute Japan). Williams test was performed to test the dose-dependent effect of LA-PTH compared with the TPTX-vehicle group. Dunnet test was performed to assess the significant differences in the LA-PTH groups compared with the sham group (Fig. 4C). Student's t-test was used to assess significance between two data sets (TPTX-vehicle vs sham).

Figure 4.

Effects of four-weeks of daily SC injection of LA-PTH on levels of serum Ca and Pi and urine Ca in TPTX rats. TPTX rats were injected daily for four weeks via the subcutaneous route with vehicle or LA-PTH at varying doses, and sham control rats were injected with vehicle, and blood and urine samples were collected and assessed for calcium or phosphate. A) Serum calcium (sCa) levels were assessed on the indicated days at times just prior to injection (0h) and 10-hours post injection (10h). B) Serum inorganic phosphate (sPi) levels were measured in parallel with serum calcium. C) total urine was collected on day 28 in metabolic cages and assessed for calcium concentration. Data are means ± SEM; n = 6 or 5 (TPTX-vehicle, and LA-PTH 7.2 nmol/kg), *P < 0.05 LA-PTH versus TPTX-vehicle, $P < 0.05 PTH(1–84) versus TPTX-vehicle, #P < 0.05 TPTX-vehicle versus sham. C) Dunnet test was performed to assess the significant differences in the LA-PTH compared with sham. +p<0.05 LA-PTH versus sham.

Results

Binding and cAMP signaling properties on the PTHR1

The PTHR1-binding properties of LA-PTH were compared to those of PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84) by performing radioligand competition assays designed to assess binding to the R0 and RG conformations of the receptor in membranes prepared from GP-2.3 cells (HEK-293-derived cells stably expressing the hPTHR1 and glosensor cAMP reporter). At the RG conformation, assessed utilizing the radioligand 125I-M-PTH(1–15), which binds selectively to G protein-coupled PTH receptors(17), each ligand bound with a high apparent affinity, although PTH(1–84) bound with an approximately two-fold weaker affinity (IC50 = 0.28 nM) than did PTH(1–34) and LA-PTH (IC50s = 0.08 and 0.1 nM), whereas at the R0 conformation, assessed utilizing 125I-PTH(1–34) as radioligand and in the presence of GTPγS to block receptor-G protein coupling, LA-PTH bound with an approximately eight-fold higher affinity than did either PTH(1–34) or PTH(1–84) (IC50s = 1.5, 11.7 and 13.8 nM, respectively; Fig. S1, Table S1). Thus, LA-PTH exhibited a higher degree of selectivity for the R0 conformation, versus the RG conformation, than did either PTH(1–34) or PTH(1–84). The conformational selectivity profile observed here for LA-PTH on the human PTHR1 parallels that observed for this ligand on the rat PTHR1(14) and clearly differs from that observed for either PTH(1–84) or PTH(1–34), which bind comparatively weakly to R0 while maintaining similarly high affinity for RG. Consistent with the capacity of these ligands to bind with high and similar affinities to the RG (G protein-coupled) conformation of the PTHR1, they each exhibited high and similar potencies for stimulating cAMP production when assessed in dose-response assays in GP-2.3 cells (Fig. S1, Table S2).

Effects of a single IV injection of LA-PTH on serum Ca and Pi levels in TPTX rats

We then examined the capacity of a single intravenously (IV) injection of LA-PTH to modulate serum levels of calcium (sCa) and inorganic phosphorus (sPi) in TPTX rats. Base-line sCa levels were significantly reduced in TPTX rats, as compared to the levels in sham-control animals (~ 6.6 mg/dL vs. ~ 10.0 mg/dL). Injection of LA-PTH into the TPTX rats resulted in dose-dependent increases in sCa levels. The highest dose of LA-PTH tested (2.7 nmol/kg) resulted in frank hypecalcemia (sCa > 16 mg/dL) by 24 hours post-injection, while the lowest dose (0.3 nmol/kg) restored sCa levels to nearly the same levels seen in the sham control animals by 10 hours, and the restorative effect persisted for up to 48 hours (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Effects of LA-PTH administration by IV injection on serum Ca and Pi levels in TPTX rats. A) Serum calcium (sCa) levels in TPTX rats at times just prior to (t = 0) and following IV injection with either vehicle or LA-PTH at the indicated doses. Sham surgery control rats were injected with vehicle. B) Serum inorganic phosphate (sPi) levels in the same animals shown in panel B. Data are means ± SEM; n = 6 or 5 (TPTX-vehicle); *P < 0.05 LA-PTH versus TPTX-vehicle; #P < 0.05 TPTX-vehicle versus sham.

Parallel groups of animals in this study were injected IV with PTH(1–34) or PTH(1–84) at doses as high as 24.3 nmol/kg, and for each peptide, the highest tested dose (24.3 nmol/kg) induced a much more modest and more transient increase in sCa than did even the lowest dose (0.3 nmol/kg) of LA-PTH. Thus, the sCa levels in the high-dose PTH(1–34)- and PTH(1–84)-injected rats failed to attain the sCa levels seen in the sham-control animals, and the levels returned to base-line by six hours post-injection (Fig. S2A, C).

Effects of the IV-injected peptides on sPi were consistent with those observed for sCa. Thus, LA-PTH dose-dependently reduced sPi to levels well below those seen in the vehicle-injected TPTX rats, with the middle dose (0.9 nmol/kg) reducing blood Pi to levels that were similar to those seen in sham-control animals, and the sPi remained at near-normal levels for the duration of the study (72 hours, Fig. 1B). PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84), at the highest injected dose (24.3 nmol/kg), each induced significant reductions in Pi at 2-hours post-injection, but the levels did not attain the levels seen in the sham animals, and returned to vehicle-control levels by 10 hours post injection (Fig. S2B, D).

Pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of PTH analogs in TPTX rats

We then compared the pharmacokinetic properties of LA-PTH to those of PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84) by intravenously injecting the peptides at equivalent doses (24.3 nmol/kg) into TPTX rats and measuring at times after injection the blood concentrations of the peptides by methods of either mass-spectroscopy (PTH(1–34) and LA-PTH) or ELISA immuno-assay (PTH(1–84)-human-specific). As shown in Fig. 2, each peptide disappeared rapidly from the circulation such that the plasma concentrations approached the detection limit of the respective assay by the 60 minute time point, and the derived serum-half life values were within the range of 5- to 8 minutes (LA-PTH, t1/2 = 7.3 min.; PTH(1–34) t1/2 = 7.8 min.; PTH(1–84) t1/2 = 5.4 min.). The relatively rapid rate of clearance observed for LA-PTH in these studies is notable, given the prolonged (> 48hrs) calcemic/hypophosphatemic responses induced by the peptide. This rapid rate of clearance coupled with a prolonged pharmacodynamic (PD) profile of LA-PTH observed here in TPTX rats is consistent with the rapid clearance rate and prolonged calcemic/hypophosphatemic responses observed in mice for the structurally related, R0-selective analog, M-PTH(1–34)(13).

Figure 2.

Pharmacokinetics of LA-PTH, PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84) following IV injection in TPTX-operated rats. LA-PTH, PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84) were injected administered intravenously in TPTX rats at a dose of 24.3 nmol/kg and blood samples were collected from jugular vein in the presence of proteinase inhibitors (Aprotinin, Leupeptin, and EDTA) and the plasma were assessed for peptide concentrations using LC-MS/MS (PTH(1–34) and LA-PTH) or ELISA immuno assay (PTH(1–84)-human specific). The dashed lines indicate the limits of detection of the LC-MS/MS (purple). The limit of detection of the ELISA assay was 0.01 pmol/mL. The inset shows the same data plotted using linear y-axis scaling. Data are means ± SD; n = 3.

Effects of a single subcutaneous administration of LA-PTH on serum and urine Ca levels in TXPTX rats

We then assessed the capacity of LA-PTH to modulate blood calcium and phosphate levels in TXPTX rats following administration by subcutaneous (SC) injection. Single SC injections of LA-PTH at varying doses (0.3 nmol/kg to 72.9 nmol/kg) revealed dose-dependent increases in sCa, with doses of 8.1 nmol/kg and higher inducing significant effects, relative to vehicle-injected controls, that persisted for 24 hours or more (Fig. 3A). At the two highest doses of LA-PTH tested, 24.3 and 72.9 nmol/kg, the effects on sCa lasted longer than 48 hours, and the peak sCa levels rose to well above the sham-control levels with the highest dose tested. The 24-hour urine calcium (uCa) levels were not increased significantly at any dose of LA-PTH tested, relative to the levels of the sham-controls or vehicle-injected TPTX rats, except at the highest dose of LA-PTH (72.9 nmol/kg), for which the levels were significantly higher than those of the vehicle-injected controls (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of a single subcutaneous injection of LA-PTH on serum and urinary Ca levels in TPTX rats. TPTX rats were injected subcutaneously with vehicle or LA-PTH at the indicated doses, and sham control rats were injected with vehicle; and the levels of calcium in serum and urine were assessed. A) Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein at the specific time points indicated and assessed for sCa. B) Total urine was collected in metabolic cages over the time intervals of 0–24, 24–48, and 48–72 h and assessed for total urinary calcium (uCa). Data are means ± SEM; n = 8 or 7 (72.9 nmol/kg); *P < 0.05 LA-PTH versus TPTX-vehicle, #P < 0.05 TPTX-vehicle versus sham. The sCa levels in TPTX rats injected with LA-PTH at 0.3 to 72.9 nmol/kg at 2 hours were statistically higher than those in vehicle-injected TPTX rats.

Effects of repeated daily administration of LA-PTH on serum and urinary Ca and Pi, and bone parameters in TPTX rats

We then assessed the capacity of LA-PTH to modulate sCa and sPi levels in TPTX rats when administered by daily SC injection over a course of 28-days. Over the tested dose range of 0.9 to 7.2 nmol/ kg, LA-PTH dose-dependently increased sCa levels and reduced sPi levels, as measured on days 1, 7, 15 21, 27 and 28, at times just prior to injection (24 hrs after the previous injection) as well as at 10 hrs post-injection (Fig. 4A, B). These studies revealed a tendency for the peak (10 hr) sCa and sPi responses to LA-PTH to increase during the initial phase of the injection period, most apparent by comparing the responses on day 21 to those observed on day 1. The reason for this apparent change in the initial LA-PTH response profile is currently uncertain (see Discussion). In any case, the sCa and sPi levels in the TPTX rats injected once-daily with LA-PTH at a dose of 1.8 nmol/kg were consistently and significantly modulated, and over the major portion of the test period, were comparable to the levels seen in intact sham-control animals.

Analyses of bone structural parameters by micro-computed tomography (µCT) demonstrated that TPTX surgery resulted in significant increases in trabecular bone, as measured on day 33 post-surgery and within a defined zone of the distal femur, and that treatment with LA-PTH caused no further change in this bone parameter. Nor did LA-PTH alter cortical bone parameters measured at the mid-femur, with the exception of a slight (~11%) decrease in cortical bone volume and a significant increase of cortical porosity that occurred with the highest dose (7.2 nmol/kg) of LA-PTH (Fig. S3 and Table. S3). Consistent with these µCT data, DXA analyses of the whole femur and lumbar spine revealed no significant change in bone mineral density with LA-PTH treatment, while measurements of urinary CTX, urinary Ca and serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D revealed increases in these parameters only with the highest dose of LA-PTH (Fig. 4C; Fig. S4; Table. S3).

A parallel group of TPTX-rats injected once daily with PTH(1–84) at a single dose of 9 nmol/kg (SC) exhibited no persistent increase in sCa and only marginal reductions in sPi levels, as compared to the levels in vehicle-injected TPTX rats (Fig. S5A, B), while lumbar and femur BMD, as well as trabecular number at the distal femur were significantly increased (Fig. S3 and Table. S3). Thus, over a four-week test period and at a daily SC dose of 1.8 nmol/kg, LA-PTH achieved good control of sCa and sPi levels without inducing excessive bone resorption or hypercalciuria, and was markedly more effective in regulating blood Ca and Pi than was a considerably higher dose of PTH(1–84).

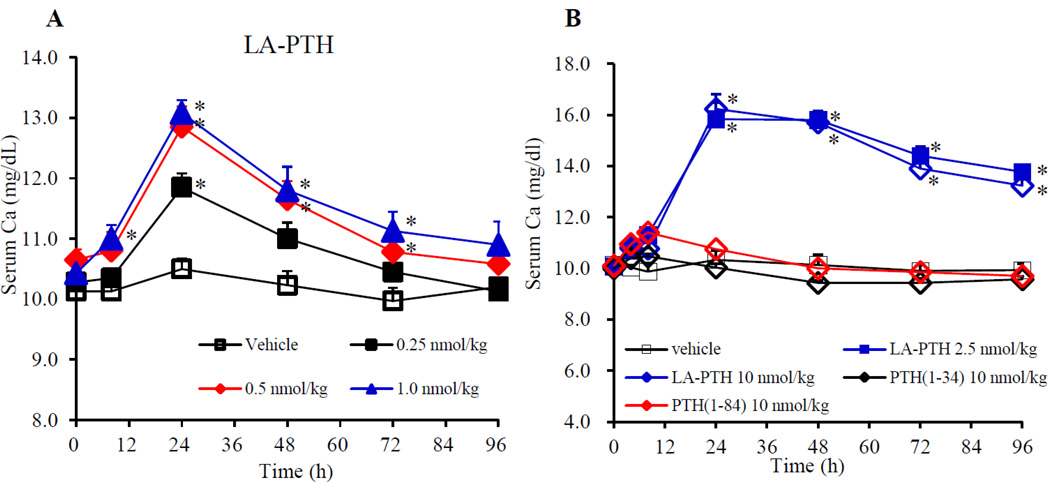

Effects on serum Ca levels in monkeys

Finally, we assessed the capacity of LA-PTH to modulate sCa in cynomologus monkeys. In the first of two experiments, LA-PTH was injected SC at a dose of either 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 nmol/kg into three animals for each dose. Figure 5A shows that even at the lowest dose (0.25 nmol/kg) LA-PTH significantly increased sCa levels by the 24 hour post-injection time point (sCa = ~ 11.9 mg/dL, vs. ~10.5 mg/dL in vehicle controls); the next two highest doses of LA-PTH elevated sCa to even higher levels (~ 13 mg/dL at the 24-hour peak) and the levels remained significantly elevated for as long as 72 hours. In the second experiment, LA-PTH was injected SC at a dose of either 2.5 or 10.0 nmol/kg, and PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84) were injected, each at a dose of 10 nmol/kg. Figure 5B shows that injection of LA-PTH at 2.5 and 10.0 nmol/kg induced frank hypercalemia (sCa ~13.0 – 16.0 mg/dL), and the levels remained elevated for at least four days post-injection. In contrast, PTH(1–84) elevated sCa only modestly (peak level ~ 11.4 mg/dL), and sCa returned to vehicle-control levels by 24 hours, while PTH(1–34) was even less effective. Thus, as compared to PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84), LA-PTH administered by SC injection exhibited enhanced and prolonged efficacy for increasing serum calcium levels in monkeys.

Figure 5.

Effects of LA-PTH, PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84) on sCa levels in monkeys. In experiment 1, cynomologus monkeys were injected SC with either vehicle, or low doses of LA-PTH (A); in experiment 2, cynomologus monkeys were injected with higher doses of LA-PTH, PTH(1–34) or PTH(1–84) (B), and at the time indicated, blood samples were collected from the saphenous vein and assessed for sCa. Data are means ± SEM; n = 3, PTH(1–84), n = 2; *P < 0.05 LA-PTH or PTH(1–34) versus vehicle; statistical analysis of PTH(1–84) was not performed.

Discussion

These studies demonstrate that LA-PTH, relative to the unmodified peptides, PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84), mediates enhanced and prolonged effects on blood Ca and Pi levels in TPTX rats, an animal model of hypoparathyroidism. These prolonged actions of LA-PTH can most simply be attributed to the enhanced affinity with which the analog binds to the PTHR1 R0 conformation, and the prolonged cAMP signaling responses that result from such binding(13,14). The mechanism is clearly not based on extended pharmacokinetics, because the PK profile of LA-PTH was found to be very comparable to that of PTH(1–34) and PTH(1–84) (Fig. 2). The results obtained here in TPTX rats and in monkeys support and extend previous studies in which LA-PTH and related analogs were shown to mediate prolonged signaling actions in cells expressing the rat PTHR1 and prolonged calcemic actions in mice or rats without evidence of extended pharmacokinetics(13,14,23) (24,25).

A key finding of our study was that after four-weeks of daily SC injection, LA-PTH, at an optimal dose of 1.8 nmol/kg, increased sCa levels in TPTX rats to near normal (sham-control) levels without increasing urinary Ca excretion. Increasing serum calcium without causing hypercalciuria is an important goal to achieve for any agent with potential clinical application to HP. In an earlier study we found that a related analog, called SP-PTH, which lacks the A18,A22,K26 modifications of LA-PTH but nevertheless exhibits high affinity for the R0 conformation of the PTHR1, when given at a dose of 4.0 nmol/kg to TPTX rats over a 10-day period, elevated serum calcium to near-normal levels (peak Ca of ~10.8 mg/dL at 8 hours, declining to ~ 7.2 mg/dL at 24 hours), again without significantly increasing urine Ca levels, whereas in contrast, 1α(OH)Vitamin-D3, used at a dose (oral 0.2 µg/kg) to achieve similar sham-levels of serum calcium, resulted in significant (P < 0.05) increases in urine calcium(24). These findings support the notion that PTH analogs that mediate prolonged actions via binding with high affinity to the R0 conformation of PTHR1 can be potential leads towards new directions in HP therapy.

The underlying mechanisms that account for the prolonged pharmacodynamic actions of LA-PTH are not completely understood, but may involve processes of extended ligand-receptor residence times(26) coupled with G protein-mediated signaling from within intracellular compartments (i.e. endosomes) of target cells(20,23). In any case, the responsible mechanisms bring about a therapeutically favorable but discordant PK/PD relationship — a serum half-life of less than eight minutes, as measured here in rodents, versus biological effects on calcium and phosphate blood levels lasting 24 hours or more, depending on the dose. This PK/PD relationship is clearly different from that observed for another class of long-acting PTH analogs that contain backbone modifications, as the prolonged biological actions of these compounds is associated with an extended pharmacokinetic profile, which is thought to arise, in part, from enhanced resistance to serum proteases(27).

Highlighting the pronounced efficacy of LA-PTH in vivo, we observed that repeated daily injection of PTH(1–84) at a dose of 9 nmol/kg sc in rats resulted in little, if any, change in blood calcium or phosphate, whereas LA-PTH, injected at a five-, or even 10-fold lower dose resulted in significant and sustained elevations in blood calcium and lowering of blood phosphorus (Figs. 4 and S-5). Another study in rats reported little or no change in serum calcium or phosphorus following daily injection of PTH(1–34) at a dose of 20 nmol/kg sc, twice that used here for PTH(1–84)(28). In humans, PTH(1–84) at the clinical dose of 100 µg (~0.2 nmol/kg, sc) produces sustained elevations in serum calcium and reductions in serum phosphorus, effects that, at least in part, can be attributed to the prolonged serum half-time (2.2 hours) that PTH(1–84) exhibits when injected sc into the thigh(8). The extent to which differences in pharmacokinetics might account for any difference in efficacy that PTH(1–84) exhibits in rats versus humans is unknown, although it is worth noting that the true serum half-life of PTH(1–84) in the blood is five minutes or less in humans(10), similar to what we measured here in the rat following iv injection. In any case, the property of delayed sc absorption with more prolonged action has proven to be beneficial in the clinical results reported for PTH(1–84)(8,9). The biological actions of LA-PTH in humans remain to be investigated.

In our 4-week once –daily (QD) studies in rats, we noted that the responses in calcium and phosphate levels for each of the administered doses of LA-PTH gradually increased over the first 21 days, but then seemed more constant thereafter. The mechanisms that account for these changes in the response profile are unknown, but could potentially involve a cumulative process of binding of the ligand to receptors in target cells until an equilibrium state is reached, at which point the biological responses stabilize(26). Further work is needed, however, to understand fully how the effectiveness of LA- PTH administration might change over time, and how various molecular and cellular mechanisms contribute to the overall response. Elucidating such issues in preclinical studies could be important to help guide any future clinical investigations on the dose effectiveness of LA-PTH.

Long-term effects on skeletal integrity are also important factors to consider in potential HP therapy. Baseline BMD is significantly higher in HP patients than in normal adults, due to reduced bone turnover(29), and PTH injection is well known to modulate bone-remodeling(30). In our study in TPTX rats, we observed that 33 days after surgery the animals had significant increases in trabecular bone parameters, as measured at the distal femur. While treatment with LA-PTH at the highest dose (7.2 nmol/kg) decreased cortical bone, treatment at the lower dose of 1.8 nmol/kg, which was found to optimally modulate blood Ca levels, did not significantly change any of the bone structural parameters measured. Findings in these and other pre-clinical studies will be important to consider in any eventual testing of this promising, novel ligand in the clinical management of patients with hypoparathyroidism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and was partially supported by NIH grant NIDDK 11794 to TJG and JTP, and AR066261 to TJG.

The authors thank staff of Chugai Research Institute for Medical Science, Inc. for the technical assistance of in vivo studies.

Footnotes

Disclosures

MS, EJ, HN, TW, MO, MN, KA, TT, YK are employees of Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.. TJG and JTP received a research grant from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd..

Study design: MS, HN, MO, MN, TT, YK, JTP, TJG, YK. Study conduct: MS, EJ, HN, TW, MN, KA. Data analysis: MS, EJ, HN, MO, TW, MN, KA, TJG. Drafting manuscript: MS, JTP, TJG and YK. Revising manuscript: MS, JTP and TJG. MS takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Bilezikian JP, Khan A, Potts JT, Jr, Brandi ML, Clarke BL, Shoback D, Juppner H, D'Amour P, Fox J, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L, Rubin MR, Dempster D, Gafni R, Collins MT, Sliney J, Sanders J. Hypoparathyroidism in the adult: epidemiology, diagnosis, pathophysiology, target-organ involvement, treatment, and challenges for future research. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(10):2317–2337. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shoback D. Clinical practice. Hypoparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):391–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0803050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell DM, Regan S, Cooley MR, Lauter KB, Vrla MC, Becker CB, Burnett-Bowie SA, Mannstadt M. Long-term follow-up of patients with hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):4507–4514. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Underbjerg L, Sikjaer T, Mosekilde L, Rejnmark L. Cardiovascular and renal complications to postsurgical hypoparathyroidism: a Danish nationwide controlled historic follow-up study. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(11):2277–2285. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winer KK, Yanovski JA, Cutler GB., Jr Synthetic human parathyroid hormone 1–34 vs calcitriol and calcium in the treatment of hypoparathyroidism. JAMA. 1996;276(8):631–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winer KK, Yanovski JA, Sarani B, Cutler GB., Jr A randomized, cross-over trial of once-daily versus twice-daily parathyroid hormone 1–34 in treatment of hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(10):3480–3486. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.10.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin MR, Sliney J, Jr, McMahon DJ, Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP. Therapy of hypoparathyroidism with intact parathyroid hormone. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(11):1927–1934. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1149-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sikjaer T, Amstrup AK, Rolighed L, Kjaer SG, Mosekilde L, Rejnmark L. PTH(1–84) replacement therapy in hypoparathyroidism: A randomized controlled trial on pharmacokinetic and dynamic effects after 6 months of treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(10):2232–2243. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannstadt M, Clarke BL, Vokes T, Brandi ML, Ranganath L, Fraser WD, Lakatos P, Bajnok L, Garceau R, Mosekilde L, Lagast H, Shoback D, Bilezikian JP. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–84) in hypoparathyroidism (REPLACE): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(4):275–283. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nussbaum SR, Potts JT., Jr Immunoassays for parathyroid hormone 1–84 in the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6(Suppl 2):S43–S50. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650061412. discussion S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winer KK, Zhang B, Shrader JA, Peterson D, Smith M, Albert PS, Cutler GB., Jr Synthetic human parathyroid hormone 1–34 replacement therapy: a randomized crossover trial comparing pump versus injections in the treatment of chronic hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(2):391–399. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winer KK, Fulton KA, Albert PS, Cutler GB., Jr Effects of pump versus twice-daily injection delivery of synthetic parathyroid hormone 1–34 in children with severe congenital hypoparathyroidism. J Pediatr. 2014;165(3):556–563. e551. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okazaki M, Ferrandon S, Vilardaga JP, Bouxsein ML, Potts JT, Jr, Gardella TJ. Prolonged signaling at the parathyroid hormone receptor by peptide ligands targeted to a specific receptor conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(43):16525–16530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808750105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda A, Okazaki M, Baron DM, Dean T, Khatri A, Mahon M, Segawa H, Abou-Samra AB, Juppner H, Bloch KD, Potts JT, Jr, Gardella TJ. Critical role of parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor-1 phosphorylation in regulating acute responses to PTH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):5864–5869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301674110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu M, Potts JT, Jr, Gardella TJ. Minimization of parathyroid hormone. Novel amino-terminal parathyroid hormone fragments with enhanced potency in activating the type-1 parathyroid hormone receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(29):21836–21843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909861199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu M, Carter PH, Khatri A, Potts JT, Jr, Gardella TJ. Enhanced activity in parathyroid hormone-(1–14) and -(1–11): novel peptides for probing ligand-receptor interactions. Endocrinology. 2001;142(7):3068–3074. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dean T, Linglart A, Mahon MJ, Bastepe M, Juppner H, Potts JT, Jr, Gardella TJ. Mechanisms of ligand binding to the parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related protein receptor: selectivity of a modified PTH(1–15) radioligand for GalphaS-coupled receptor conformations. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(4):931–943. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrandon S, Feinstein TN, Castro M, Wang B, Bouley R, Potts JT, Gardella TJ, Vilardaga JP. Sustained cyclic AMP production by parathyroid hormone receptor endocytosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(10):734–742. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feinstein TN, Wehbi VL, Ardura JA, Wheeler DS, Ferrandon S, Gardella TJ, Vilardaga JP. Retromer terminates the generation of cAMP by internalized PTH receptors. Nature Chem Biol. 2011;7(5):278–284. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vilardaga JP, Jean-Alphonse FG, Gardella TJ. Endosomal generation of cAMP in GPCR signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(9):700–706. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardella TJ, Rubin D, Abou-Samra AB, Keutmann HT, Potts JT, Jr, Kronenberg HM, Nussbaum SR. Expression of human parathyroid hormone-(1–84) in Escherichia coli as a factor X-cleavable fusion protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(26):15854–15859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Muller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(7):1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheloha RW, Gellman SH, Vilardaga JP, Gardella TJ. PTH receptor-1 signalling-mechanistic insights and therapeutic prospects. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimizu M, Ichikawa F, Noda H, Okazaki M, Nakagawa C, Tamura T, Gardella TJ, Potts JT, Ogata E, Kuromaru O, Kawabe Y. A New Long-Acting PTH/PTHrP Hybrid Analog that Binds to a Distinct PTHR Conformation has Superior Efficacy in a Rat Model of Hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(S1):S128. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hattersley G, Dean T, Corbin BA, Bahar H, Gardella TJ. Binding Selectivity of Abaloparatide for PTH-type-1-Receptor Conformations and Effects on Downstream Signaling. Endocrinology. 2015 doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1726. en20151726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahl G, Akerud T. Pharmacokinetics and the drug-target residence time concept. Drug Discovery Today. 2013;18(15–16):697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheloha RW, Maeda A, Dean T, Gardella TJ, Gellman SH. Backbone modification of a polypeptide drug alters duration of action in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(7):653–655. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dobnig H, Turner RT. The effects of programmed administration of human parathyroid hormone fragment (1–34) on bone histomorphometry and serum chemistry in rats. Endocrinology. 1997;138(11):4607–4612. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin MR, Dempster DW, Zhou H, Shane E, Nickolas T, Sliney J, Jr, Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP. Dynamic and structural properties of the skeleton in hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(12):2018–2024. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin MR, Dempster DW, Sliney J, Jr, Zhou H, Nickolas TL, Stein EM, Dworakowski E, Dellabadia M, Ives R, McMahon DJ, Zhang C, Silverberg SJ, Shane E, Cremers S, Bilezikian JP. PTH(1–84) administration reverses abnormal bone-remodeling dynamics and structure in hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(11):2727–2736. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.