Abstract

Data on the effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors on fracture risk are conflicting. Here, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors. Electronic databases were searched for relevant published articles, and unpublished studies presented at ClinicalTrials.gov were searched for relevant clinical data. Eligible studies included prospective randomized trials evaluating DPP-4 inhibitors versus placebo or other anti-diabetic medications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Study quality was determined using Jadad scores. Statistical analyses were performed to calculate the risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using fixed-effects models. There were 62 eligible RCTs with 62,206 participants, including 33,452 patients treated with DPP-4 inhibitors. The number of fractures was 364 in the exposed group and 358 in the control group. The overall risk of fracture did not differ between patients exposed to DPP-4 inhibitors and controls (RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.83–1.10; P = 0.50). The results were consistent across subgroups defined by type of DPP-4 inhibitor, type of control, and length of follow-up. The study showed that DPP-4 inhibitor use does not modify the risk of bone fracture compared with placebo or other anti-diabetic medications in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes is a highly prevalent disease, especially in elderly and obese patients. Cumulative evidence shows that type 2 diabetes is associated with an increased risk of bone fracture1,2. Several anti-diabetes drugs have been reported to increase the incidence of fractures3,4.

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, a class of incretin based agents for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, have intermediate efficacy regarding glucose control with a satisfactory tolerability profile5,6,7. Data on the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on fracture risk are conflicting. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) suggested that DPP-4 inhibitors reduced the risk of bone fracture8. However, a recent retrospective population-based cohort study concluded that DPP-4 inhibitors were not associated with fracture risk compared with controls and other non-insulin anti-diabetic drugs (NIADs)9.

The association between DPP-4 inhibitors and the risk of fracture in patients with type 2 diabetes has not been well established. We therefore performed a meta-analysis of randomized trials to provide a more robust answer regarding the risk of fracture in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with DPP-4 inhibitors.

Results

Search results

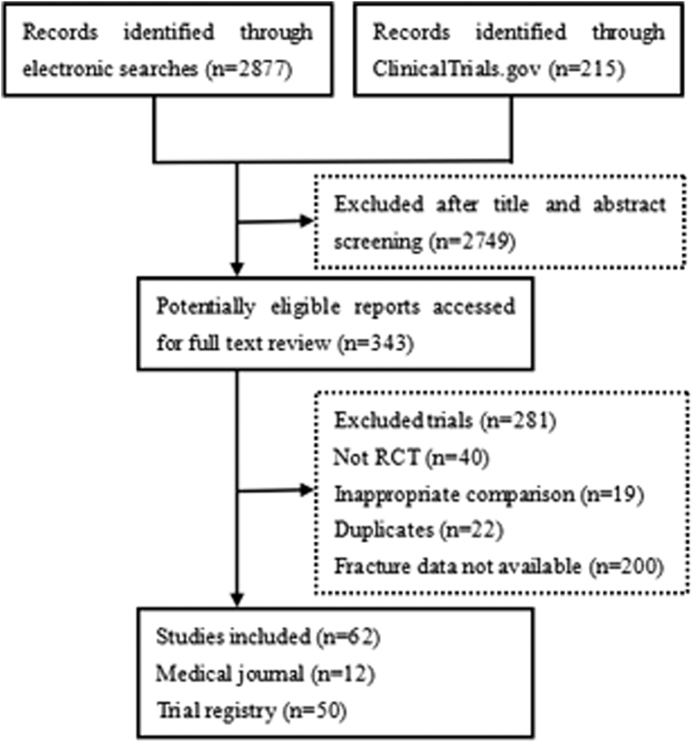

A total of 3092 unique titles and abstracts were identified in initial searches of the electronic database. After screening titles and abstracts, we retrieved 343 reports for full text screening. A total of 62 RCTs, including 13 from journals10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 and 49 from the trial registry (available from https://clinicaltrials.gov) were included in the final analysis. The details of the study selection flow are described in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Trial flow diagram.

Study characteristics

The baseline characteristics of trials are included in Table 1 and the quality assessment results are listed in Table S1. A total of 62,206 patients (33,452 in the experimental group and 28,754 in the control group) were included in this analysis, of which 722 had fractures (364 in the experimental group and 358 in the control group). The age of the included patients ranged from 49.7 to 74.9 years. The inhibitors tested in the trials were alogliptin in 7, linagliptin in 13, saxagliptin in 9, sitagliptin in 27, anagliptin in 1, and vildagliptin in 5. The duration of treatment ranged from 12 weeks to 40 months. Forty-three trials were placebo-controlled and 28 used an active comparator, while nine trials included both placebo and active comparator arms. Active comparators included albiglutide, canagliflozin, empagliflozin, glipizide, glimepiride, metformin, voglibose, or thiazolidinediones. Of the 62 trials included in the meta-analysis, 61 were double blind trials.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in primary analysis.

| Study | NCT code | DPP-4 | Comparator(s) | N. of patients | Duration (weeks) | Age (years) | HbA1c (%) | Fracture | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPP-4 | Control | DPP-4 | Control | |||||||

| Bosi10 | NCT00432276 | ALOG | Pioglitazone | 404 | 399 | 52 | 55 | 8.3 | 6 | 4 |

| NCT00286468 | NCT00286468 | ALOG | Placebo | 401 | 99 | 26 | 57 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| NCT01023581 | NCT01023581 | ALOG | Placebo/metformin | 450 | 334 | 26 | 53.5 | 8.5 | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00856284 | NCT00856284 | ALOG | Glipizide | 1765 | 874 | 104 | 55.4 | 7.6 | 6 | 4 |

| NCT00328627 | NCT00328627 | ALOG | Placebo/pioglitazone | 1037 | 517 | 26 | 54.4 | 8.6 | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00707993 | NCT00707993 | ALOG | Glipizide | 222 | 219 | 52 | 69.9 | NR | 2 | 1 |

| White11 | NCT00968708 | ALOG | Placebo | 2701 | 2679 | 40 months | 60.9 | 8 | 38 | 50 |

| NCT01183013 | NCT01183013 | LINA | Placebo | 392 | 409 | 54 | 57.1 | 8.11 | 1 | 0 |

| NCT00915772 | NCT00915772 | LINA | Placebo/metformin | 171 | 170 | 54 | 55.8 | 7.5 | 1 | 1 |

| NCT00798161 | NCT00798161 | LINA | Placebo/metformin | 428 | 363 | 24 | 55.2 | 8.91 | 1 | 1 |

| NCT01438814 | NCT01438814 | LINA | Placebo | 344 | 345 | 14 | 53 | NR | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00601250 | NCT00601250 | LINA | Placebo | 523 | 177 | 24 | 56.5 | 8.08 | 2 | 0 |

| NCT01084005 | NCT01084005 | LINA | Placebo | 162 | 79 | 24 | 74.9 | 7.78 | 2 | 0 |

| NCT00954447 | NCT00954447 | LINA | Placebo | 631 | 630 | 52 | 60 | 8.3 | 6 | 5 |

| NCT00602472 | NCT00602472 | LINA | Placebo | 792 | 263 | 24 | 58.1 | 8.14 | 3 | 0 |

| NCT00800683 | NCT00800683 | LINA | Placebo | 68 | 65 | 52 | 64.4 | 8.2 | 2 | 0 |

| NCT00621140 | NCT00621140 | LINA | Placebo | 336 | 167 | 24 | 55.7 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| NCT01204294 | NCT01204294 | LINA | Metformin | 228 | 124 | 52 | 60.9 | NR | 1 | 0 |

| NCT01215097 | NCT01215097 | LINA | Placebo | 205 | 100 | 24 | 55.5 | 7.99 | 1 | 0 |

| Barnett12 | NCT01084005 | LINA | Placebo | 162 | 79 | 24 | 74.9 | 7.78 | 2 | 0 |

| Barnett13 | NCT00757588 | SAXA | Placebo | 304 | 151 | 52 | 57.2 | 8.7 | 2 | 3 |

| Hollander14 | NCT00295633 | SAXA | Placebo | 381 | 184 | 24 | 54 | 8 | 5 | 1 |

| Scirica15 | NCT01107886 | SAXA | Placebo | 8280 | 8212 | 2.9 years | 65 | NR | 241 | 240 |

| NCT01006603 | NCT01006603 | SAXA | Glimepiride | 359 | 359 | 52 | 72.6 | NR | 4 | 1 |

| NCT00121667 | NCT00121667 | SAXA | Placebo | 564 | 179 | 206 | 54.57 | 8.1 | 4 | 0 |

| NCT00575588 | NCT00575588 | SAXA | Glipizide | 428 | 430 | 52 | 57.55 | 7.7 | 4 | 2 |

| NCT00614939 | NCT00614939 | SAXA | Placebo | 85 | 85 | 52 | 66.5 | NR | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00327015 | NCT00327015 | SAXA | Placebo/metformin | 643 | 328 | 76 | 52 | 9.5 | 3 | 0 |

| NCT00661362 | NCT00661362 | SAXA | Placebo | 283 | 287 | 24 | 54 | 7.9 | 3 | 0 |

| NCT00509236 | NCT00509236 | SITA | Glipizide | 64 | 65 | 54 | 59.5 | NR | 2 | 0 |

| NCT01076088 | NCT01076088 | SITA | Placebo/metformin | 367 | 377 | 24 | 52.7 | 8.7 | 0 | 3 |

| NCT00509262 | NCT00509262 | SITA | Glipizide | 211 | 212 | 54 | 64.2 | 7.8 | 1 | 1 |

| NCT01076075 | NCT01076075 | SITA | Pioglitazone | 210 | 212 | 54 | 54.9 | 8.4 | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00885352 | NCT00885352 | SITA | Placebo | 157 | 156 | 26 | 56.1 | 8.7 | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00395343 | NCT00395343 | SITA | Placebo | 322 | 319 | 24 | 57.8 | 8.7 | 1 | 0 |

| NCT00722371 | NCT00722371 | SITA | Placebo/pioglitazone | 691 | 693 | 54 | 57 | NR | 3 | 1 |

| NCT01462266 | NCT01462266 | SITA | Placebo | 329 | 329 | 24 | 58.8 | NR | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00305604 | NCT00305604 | SITA | Placebo | 102 | 104 | 24 | 71.9 | 7.8 | 0 | 2 |

| NCT00411554 | NCT00411554 | SITA | Voglibose | 163 | 156 | 12 | 60.7 | 7.8 | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00103857 | NCT00103857 | SITA | Placebo/ metformin | 372 | 540 | 104 | 53.4 | 9 | 1 | 3 |

| NCT01177813 | NCT01177813 | SITA | Empagliflozin | 223 | 448 | 31 | 55 | NR | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00449930 | NCT00449930 | SITA | Metformin | 528 | 522 | 24 | 56 | 7.3 | 1 | 0 |

| NCT00701090 | NCT00701090 | SITA | Glimepiride | 516 | 519 | 30 | 56.3 | 7.5 | 2 | 1 |

| NCT00086515 | NCT00086515 | SITA | Glipizide | 464 | 237 | 24 | 54.5 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| NCT01098539 | NCT01098539 | SITA | Albiglutide | 246 | 249 | 26 | 63.3 | NR | 0 | 2 |

| NCT00086502 | NCT00086502 | SITA | Placebo | 175 | 178 | 24 | 56.2 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| NCT00094770 | NCT00094770 | SITA | Glipizide | 588 | 584 | 104 | 56.7 | 7.7 | 3 | 3 |

| NCT01289990 | NCT01289990 | SITA | Placebo/empagliflozin | 223 | 223 | 76 | 55.6 | NR | 0 | 2 |

| NCT00482729 | NCT00482729 | SITA | Placebo | 625 | 621 | 44 | 49.7 | 9.87 | 1 | 2 |

| NCT00397631 | NCT00397631 | SITA | Placebo | 261 | 259 | 24 | 50.9 | 9.5 | 1 | 0 |

| NCT01106677 | NCT01106677 | SITA | Canagliflozin | 366 | 735 | 52 | 55.4 | NR | 0 | 1 |

| NCT01137812 | NCT01137812 | SITA | Canagliflozin | 378 | 377 | 52 | 56.5 | NR | 1 | 2 |

| NCT01106690 | NCT01106690 | SITA | Canagliflozin | 115 | 227 | 52 | 57.4 | NR | 0 | 2 |

| NCT00881530 | NCT00881530 | SITA | Placebo | 56 | 56 | 78 | 58.6 | NR | 0 | 1 |

| Iwamoto16 | NR | SITA | Voglibose | 163 | 156 | 12 | 60.7 | 7.8 | 0 | 1 |

| Raz17 | NCT00337610 | SITA | Placebo | 96 | 94 | 30 | 54.8 | 9.2 | 0 | 1 |

| Bosi18 | NCT00468039 NCT00382096 | VILDA | Placebo | 292 | 292 | 24 | 52.8 | 8.65 | 1 | 0 |

| Fonseca19 | NCT00099931 | VILDA | Placebo | 144 | 152 | 24 | 59.2 | 8.4 | 0 | 1 |

| Iwamoto20 | NR | VILDA | Voglibose | 188 | 192 | 12 | 60.3 | 7.5 | 0 | 2 |

| Pan21 | NR | VILDA | Placebo | 294 | 144 | 24 | 54.2 | 8.05 | 1 | 0 |

| Scherbaum22 | NCT00101712 | VILDA | Placebo | 156 | 155 | 52 | 63.3 | 6.7 | 0 | 1 |

| Yang23 | NR | ANAG | Placebo | 60 | 48 | 24 | 56.2 | 7.14 | 3 | 0 |

ALOG, alogliptin; LINA, linagliptin; SAXA, saxagliptin; SITA, sitagliptin; VILDA, vildagliptin; ANAG, anagliptin;NR, nor reported.

Risk ratio of fracture

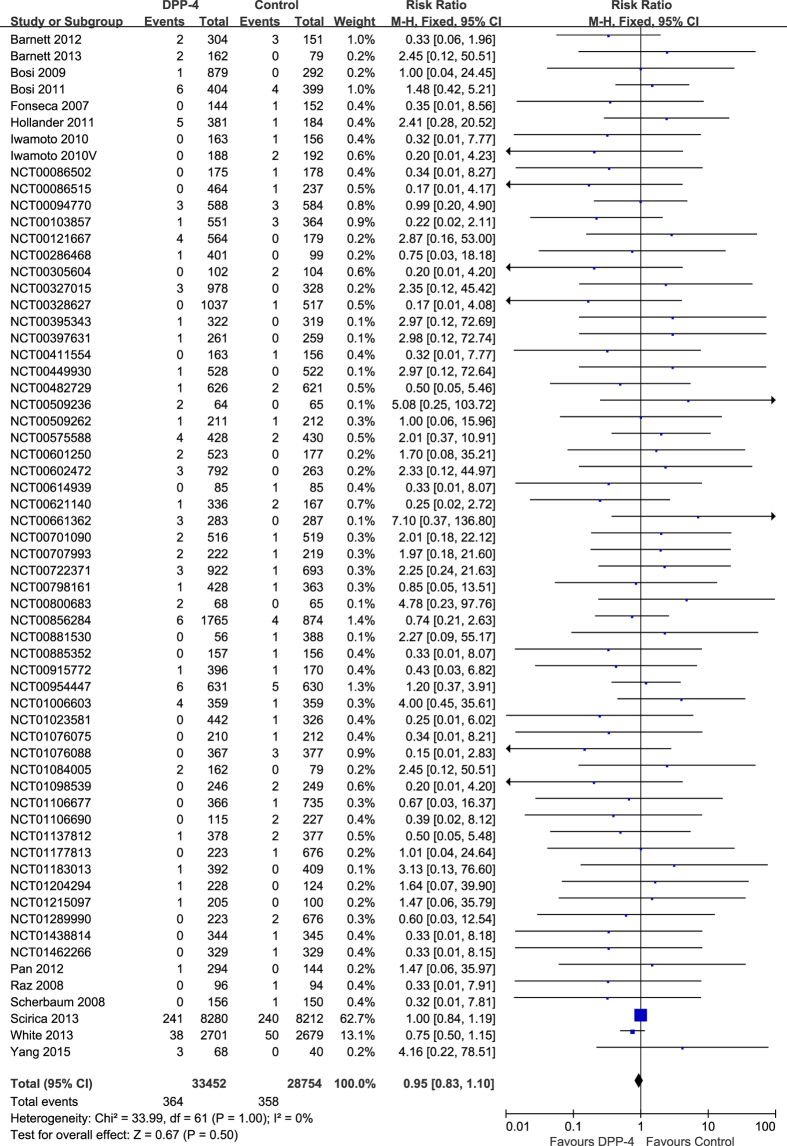

A meta-analysis was performed to calculate the overall risk ratio (RR) of fracture associated with DPP-4 inhibitors versus control. Analysis of 62 trials showed that DPP-4 inhibitors were not associated with a significantly increased risk of fracture. The RR of fracture for patients treated with DPP-4 inhibitors compared with that for controls was 0.95 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.83–1.10, P = 0.50), with insignificant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Fig. 2). The evidence quality was moderate to high (Table S2).

Figure 2. Risk of fractures between patients with type 2 diabetes treated with DPP-4 inhibitors or control.

Subgroup analysis according to drug type

Subgroup analysis was performed to determine whether drug type had an effect on the RR of fracture with DPP-4 inhibitors. The RR of fracture with individual DPP-4 inhibitors was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.55–1.13, P = 0.19) for alogliptin (seven trials with 12,085 individuals, enrolling 53 patients with fracture in the experimental group and 61 patients with fracture in the control group), 1.25 (0.66–2.38, P = 0.50) for linagliptin (13 trials with 7638 individuals, enrolling 23 patients with fracture in the experimental group and 10 patients with fracture in the control group), 1.03 (0.87–1.22, P = 0.73) for saxagliptin (nine trials with 21,877 individuals, enrolling 266 patients with fracture in the experimental group and 248 patients with fracture in the control group), 0.66 (0.41–1.06, P = 0.08) for sitagliptin (27 trials with 17,907 individuals, enrolling 17 patients with fracture in the experimental group and 35 patients with fracture in the control group), 4.16 (0.22–78.51, P = 0.34) for anagliptin (one trial with 108 individuals, enrolling three patients with fracture in the experimental group and 0 patients with fracture in the control group) and 0.47 (0.13–1.78, P = 0.27) for vildagliptin (five trials with 2591 individuals, enrolling two patients with fracture in the experimental group and four patients with fracture in the control group). There were no statistically significant differences in the risk of fracture between individual DPP-4 inhibitors (P = 0.22) (Table 2). The evidence quality was moderate to high (Table S2).

Table 2. Risk ratio of fracture by subgroup analyses.

| Subgroup | Studies n | No. of fracture | No. of participants | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPP-4 | Control | DPP-4 | Control | RR | Group difference | |||

| Overall Individual DPP-4 | 62 | 364 | 358 | 33452 | 28754 | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) | 0.50 | NA |

| Alogliptin | 7 | 53 | 61 | 6972 | 5113 | 0.79 (0.55, 1.14) | 0.20 | 0.37 |

| Linagliptin | 13 | 23 | 10 | 4667 | 2971 | 1.19 (0.60, 2.38) | 0.62 | |

| Saxagliptin | 9 | 266 | 248 | 11662 | 10215 | 1.02 (0.86, 1.21) | 0.84 | |

| Sitagliptin | 27 | 17 | 35 | 8422 | 9485 | 0.67 (0.39, 1.15) | 0.15 | |

| Anagliptin | 1 | 3 | 0 | 68 | 40 | 4.16 (0.22, 78.51) | 0.34 | |

| Vildagliptin | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1661 | 930 | 0.50 (0.12, 2.05) | 0.33 | |

| Duration | ||||||||

| ≥52 weeks | 28 | 332 | 330 | 21645 | 19996 | 0.97 (0.83, 1.13) | 0.69 | 0.37 |

| <52 weeks | 34 | 32 | 28 | 11807 | 8758 | 0.76 (0.46, 1.27) | 0.29 | |

| Comparators | ||||||||

| Active drug | 28 | 24 | 35 | 7594 | 9179 | 0.91 (0.54, 1.52) | 0.71 | 0.88 |

| Placebo | 43 | 340 | 334 | 26235 | 21718 | 0.95 (0.81, 1.10) | 0.44 | |

NA, not applicable.

Subgroup analysis according to duration

Given the potential effect of duration of treatment on the association of DPP-4 inhibitors with risk of fracture, we performed a subgroup analysis stratified according to the length of follow-up. For a duration of ≥52 weeks with 41,641 participants, no statistically significant difference was observed between patients in the DPP4i and control groups (RR = 0.98, 95% CI, 0.84–1.13, P = 0.75), including 662 patients with fracture (332 in the experimental group and 330 in the control group). No significantly increased risk of fracture was observed for a duration of <52 weeks with 20,565 participants (RR = 0.78, 95% CI, 0.51–1.21, P = 0.28) including 60 patients with fracture (32 in the experimental group and 28 in the control group). There were no statistically significant differences in the risk of fracture according to the length of follow-up (P = 0.35) (Table 2). The evidence quality was moderate to high (Table S2).

Subgroup analysis according to control regimen

Investigation of the effect of inhibitors according to the type of control (active treatment vs. placebo) did not suggest apparent differences (P = 0.76). In trials using active drug for comparison with 16,773 participants, the RR was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.56–1.39, P = 0.58), including 59 patients with fracture (24 in the experimental group and 35 in the control group). In trials using placebo for comparison with 47,953 participants, the RR was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.82–1.10, P = 0.48), including 674 patients with fracture (340 in the experimental group and 334 in the control group) (Table 2). The evidence quality was moderate to high (Table S2).

Risk of specific fractures

Individual specific and non-specific fractures were listed in Table S3. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of specific fractures.

Publication bias

No evidence of publication bias was detected for the RR of fracture in this study (Figure S1).

Discussion

The effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on bone fractures in type 2 diabetes patients have not been well documented. Here, we performed an updated meta-analysis to provide a summary of current data. Analysis of 62 RCTs demonstrated that the use of DPP-4 inhibitors does not affect the risk of bone fracture compared with placebo or other antidiabetic medications in patients with type 2 diabetes. The results were consistent across subgroups defined by type of DPP-4 inhibitor, type of control, and length of follow-up.

Our results were in line with a recently published retrospective population-based cohort study that examined 216,816 patients and suggested that DPP-4 inhibitors were not associated with fracture risk compared with controls or other NIADs9. Our study was inconsistent with that of Monami et al.8, which showed a 40% reduction of fracture risk in DPP4-I users compared with patients taking other anti-diabetic drugs or placebo24,25,26. However, the positive effect observed in this study could be related to the limited number of trials included in the analysis. Compared with the study by Monami et al.8, our study has several strengths. First, we collected data from 62 randomized trials (N = 62,206), which together involved approximately three times as many patients as those included in the study by Monami et al. (N = 21,055)8. Second, we explored sources of heterogeneity with three priori subgroup hypotheses and the results remained robust.

Out results were largely influenced by a large RCT (N = 16,492) that compared saxagliptin with placebo and showed that the incidence of bone fracture was comparable between saxagliptin and placebo users16. However, the results remained robust after omitting that trial.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) has been suggested to have a beneficial effect on bone27,28. The enzyme DPP-4 is involved in the degradation of GLP-1, and DPP-4 inhibitors are able to inhibit this process9. However, a recent meta-analysis highlighted that the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists does not modify the risk of bone fracture in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with the use of other antidiabetic medications29. Moreover, a recent in vivo study showed that MK-0626, a DPP-4 inhibitor, had neutral effects on cortical and trabecular bone in an animal model of type 2 diabetes, and MK-0626 did not alter osteoblast differentiation30. Thus, bone quality may be more important than bone density in predicting the increased risk for fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes31.

The present meta-analysis had several limitations. First, the duration of the trials included was not long enough to analyze the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on the risk of bone fracture. We performed a subgroup analysis according to duration (≥52 weeks vs. <52 weeks) and found that the risk of fracture in different length of follow up were not significantly different. Second, fractures were not the primary endpoints in any of the included trials and were reported only as serious adverse events. Finally, no data could be obtained about gender and menopausal status. Therefore, trials with a longer follow-up duration and bone fracture as the primary endpoint are needed to further investigate the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on fracture risk.

In summary, the current analysis suggested that the use of DPP-4 inhibitor does not decrease the risk of fracture in patients with type 2 diabetes. Given the negative effects of certain anti-diabetic drugs on bone, the results of the present study may be disappointing; however, a neutral effect on bone is still reassuring.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

An extensive search of Medline, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was performed by two of the investigators (J.F. and J.Z.). Data were collected on all randomized clinical trials in humans up to March 2016. Discrepancies in abstracted data between the reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (Z.Z.). The search terms used were as follows: “DPP-4”, “dipeptidyl peptidase 4”, “alogliptin”, “linagliptin”, “saxagliptin”, “sitagliptin”, “vildagliptin”, “anagliptin”, and “dutogliptin”. The results of unpublished data were identified through a search of the www.clinicaltrials.gov website.

Study Selection

The trials that met the following criteria were included in the analysis: (a) randomized clinical trials in type 2 diabetes patients; (b) duration of at least 12 weeks; (c) patients assigned to treatment with DPP-4 inhibitors compared with placebo or active drugs; (d) data on bone fracture was available; and (f) trials with two zero events were excluded from the analysis.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The following information was extracted independently from eligible RCTs by two of the investigators (Y.H. and C.G.): author’s name, year of publication, study design, sample size, number of treatment groups, length of follow-up, mean age, and registry number. In addition, for trials in which fracture data had not been published previously, the investigators abstracted the relevant numbers from their previously established databases of adverse events. The quality of included trials was assessed using the Jadad score32, which was only used for descriptive purposes. Any discrepancies in abstracted data between the reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (Z.Z.).

Data analysis

The meta-analysis was performed following the PRISMA checklist33. The main outcome was bone fracture reported as a serious adverse event. Trials were pooled using the Mantel-Haenszel method to calculate RRs and their 95% CIs. P < 0.05 was considered significant. For studies reporting zero fracture events in a treatment or control arm, a classic half-integer continuity correction was used to calculate the RR and variance. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by using the χ2 test and the I2 statistic. Selection of the fixed- or random-effects model depended on the result of the Cochrane’s Q test. An I2 value of 50% was considered to indicate significant heterogeneity between trials34. A fixed effects model was applied if there was no statistical heterogeneity among the studies; otherwise, the random effects model was used34. Pre-defined subgroup analyses were performed for trials that included different types of DPP-4 inhibitors (alogliptin, linagliptin, saxagliptin, sitagliptin, anagliptin, and vildagliptin), different types of control (active treatment vs. placebo), and different lengths of follow-up (≥52 weeks vs. <52 weeks). Finally, publication bias was evaluated through funnel plots. Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.1 software. The criteria of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation were used to evaluate the quality of evidence by outcome.35

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Fu, J. et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and fracture risk: an updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Sci. Rep. 6, 29104; doi: 10.1038/srep29104 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. William B. White (Calhoun Cardiology Center, Department of Medicine, University of Connecticut School of Medicine) and Dr Neila Smith (Pharmacovigilence at Takeda Development Center) for providing additional data and substantial support. This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81273779). The funders had no role in the study design, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit this or future manuscripts for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.F. and J.Z. wrote the manuscript text, searched the library and reviewed all articles, Y.H., C.G. and Z.Z. extracted data and evaluated the bias. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Vestergaard P. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes–a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 18, 427–444, doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0253-4 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janghorbani M., Van Dam R. M., Willett W. C. & Hu F. B. Systematic review of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of fracture. Am J Epidemiol 166, 495–505, doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm106 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z. N., Jiang Y. F. & Ding T. Risk of fracture with thiazolidinediones: an updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Bone. 68, 115–123, doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.08.010 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monami M. et al. Bone fractures and hypoglycemic treatment in type 2 diabetic patients: a case-control study. Diabetes Care 31, 199–203, doi: 10.2337/dc07-1736 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amori R. E., Lau J. & Pittas A. G. Efficacy and safety of incretin therapy in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 298, 194–206, doi: 10.1001/jama.298.2.194 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito K. et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and HbA1c target of <7% in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 13, 594–603, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01380.x (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monami M., Ahren B., Dicembrini I. & Mannucci E. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 15, 112–120, doi: 10.1111/dom.12000 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monami M., Dicembrini I., Antenore A. & Mannucci E. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and bone fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Care 34, 2474–2476, doi: 10.2337/dc11-1099 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen J. H. et al. Use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of fracture. Bone 68, 124–130, doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.030 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosi E., Ellis G. C., Wilson C. A. & Fleck P. R. Alogliptin as a third oral antidiabetic drug in patients with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycaemic control on metformin and pioglitazone: a 52-week, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, parallel-group study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 13, 1088–1096, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01463.x (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W. B. et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 369, 1327–1335, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305889 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett A. H. et al. Linagliptin for patients aged 70 years or older with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with common antidiabetes treatments: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 382, 1413–1423, doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61500-7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett A. H., Charbonnel B., Donovan M., Fleming D. & Chen R. Effect of saxagliptin as add-on therapy in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes on insulin alone or insulin combined with metformin. Curr Med Res Opin. 28, 513–523, doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.665046 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander P. L., Li J., Frederich R., Allen E. & Chen R. Safety and efficacy of saxagliptin added to thiazolidinedione over 76 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 8, 125–135, doi: 10.1177/1479164111404575 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scirica B. M. et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 369, 1317–1326, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin monotherapy compared with voglibose in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 12, 613–622, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01197.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz I. et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 24, 537–550, doi: 10.1185/030079908x260925 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosi E., Dotta F., Jia Y. & Goodman M. Vildagliptin plus metformin combination therapy provides superior glycaemic control to individual monotherapy in treatment-naive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 11, 506–515, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01040.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca V. et al. Addition of vildagliptin to insulin improves glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 50, 1148–1155, doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0633-0 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of vildagliptin and voglibose in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 12, 700–708, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01222.x (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of vildagliptin as add-on therapy to metformin in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab 14, 737–744, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01593.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherbaum W. A. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of vildagliptin in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes and mild hyperglycaemia*. Diabetes Obes Metab. 10, 675–682, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00850.x (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. K. et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of anagliptin in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr J. 62, 449–462, doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ14-0544 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonnel B. et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin alone. Diabetes Care 29, 2638–2643, doi: 10.2337/dc06-0706 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner P. et al. Effect of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 29, 2632–2637, doi: 10.2337/dc06-0703 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadzinsky M. et al. Saxagliptin given in combination with metformin as initial therapy improves glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with either monotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 11, 611–622, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01056.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz C. et al. Signaling and biological effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 on the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 298, E634–643, doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00460.2009 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuche-Berenguer B. et al. Exendin-4 exerts osteogenic actions in insulin-resistant and type 2 diabetic states. Regul Pept. 159, 61–66, doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.06.010 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabilleau G., Mieczkowska A. & Chappard D. Use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and bone fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Diabetes 6, 260–266, doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12102 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher E. J. et al. The effect of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibition on bone in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 30, 191–200, doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2466 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagnani A. & Gonnelli S. Antidiabetic therapy effects on bone metabolism and fracture risk. Diabetes Obes Metab. 15, 784–791, doi: 10.1111/dom.12077 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad A. R. et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 17, 1–12 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J. & Altman D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj. 339, b2535, doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J. & Altman D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 327, 557–560, doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins D. et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Bmj 328, 1490, doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.