ABSTRACT

The APOBEC3 family of DNA cytosine deaminases has important roles in innate immunity and cancer. It is unclear how DNA tumor viruses regulate these enzymes and how these interactions, in turn, impact the integrity of both the viral and cellular genomes. Polyomavirus (PyVs) are small DNA pathogens that contain oncogenic potentials. In this study, we examined the effects of PyV infection on APOBEC3 expression and activity. We demonstrate that APOBEC3B is specifically upregulated by BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) infection in primary kidney cells and that the upregulated enzyme is active. We further show that the BKPyV large T antigen, as well as large T antigens from related polyomaviruses, is alone capable of upregulating APOBEC3B expression and activity. Furthermore, we assessed the impact of A3B on productive BKPyV infection and viral genome evolution. Although the specific knockdown of APOBEC3B has little short-term effect on productive BKPyV infection, our informatics analyses indicate that the preferred target sequences of APOBEC3B are depleted in BKPyV genomes and that this motif underrepresentation is enriched on the nontranscribed stand of the viral genome, which is also the lagging strand during viral DNA replication. Our results suggest that PyV infection upregulates APOBEC3B activity to influence virus sequence composition over longer evolutionary periods. These findings also imply that the increased activity of APOBEC3B may contribute to PyV-mediated tumorigenesis.

IMPORTANCE Polyomaviruses (PyVs) are a group of emerging pathogens that can cause severe diseases, including cancers in immunosuppressed individuals. Here we describe the finding that PyV infection specifically induces the innate immune DNA cytosine deaminase APOBEC3B. The induced APOBEC3B enzyme is fully functional and therefore may exert mutational effects on both viral and host cell DNA. We provide bioinformatic evidence that, consistent with this idea, BK polyomavirus genomes are depleted of APOBEC3B-preferred target motifs and enriched for the corresponding predicted reaction products. These data imply that the interplay between PyV infection and APOBEC proteins may have significant impact on both viral evolution and virus-induced tumorigenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Polyomaviruses (PyVs) are a family of small nonenveloped viruses containing an ∼5-kb circular double-stranded DNA genome. Most human PyVs establish a subclinical persistent infection in healthy individuals (1). These viruses can reactivate under various immunosuppression conditions and cause a variety of severe diseases, including cancers (2). Among them, BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) reactivation is a major concern in kidney and bone marrow transplant patients due to the possibility of development of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy and hemorrhagic cystitis, respectively (3). Recently, there have also been increasing reports demonstrating an association between BKPyV infection and the occurrence of renourinary tumors (4). JC polyomavirus (JCPyV) reactivation can lead to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a serious demyelinating disease of the brain most prevalent in AIDS patients or associated with certain immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory treatments (5). Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is so far the only human PyV directly linked to cancer, having been established to be the etiologic agent for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) (6). In most MCC cases, MCPyV is found integrated into the host DNA, leading to mutations that render the virus replication incompetent and simultaneously promoting tumorigenesis (7).

Even though PyVs have been studied since the 1950s, there are several knowledge gaps in PyV biology. First, innate immune responses to PyV infection are poorly understood. PyV large T antigens (TAgs) can induce interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (8). In contrast, studies with BKPyV infection of primary kidney cells have found little evidence of ISG activation (9). It is unclear how viral DNAs are recognized and reacted to by host immune DNA sensors. Second, there is limited knowledge with regard to how these DNA viruses evolve. For BKPyV, different subtypes of viral genomes have been demonstrated to evolve from distinct human populations, with the archetypal variants being the dominant circulating virus (10). The host cell factors that contribute to the molecular evolution of PyVs remain to be determined. Finally, although intensely studied, mechanistic details explaining how PyVs interact with cellular pathways to influence malignant transformation are still far from complete. In addition to the well-known functions of TAg to inactivate tumor suppressors such as retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and p53, novel functions of PyV oncoproteins that impact cellular proliferation, transformation, and tumorigenesis continue to be discovered (11, 12).

One arm of the innate immune response in humans is comprised of the seven-membered APOBEC3 (A3) family of single-stranded DNA cytosine-to-uracil (C-to-U) deaminases: A3A, A3B, A3C, A3D, A3F, A3G, and A3H (13). Considerable evidence has shown that these enzymes combine to suppress the replication of many different DNA-based viruses (13, 14). Susceptible pathogens include retroviruses, parvoviruses, herpesviruses, papillomaviruses, and hepadnaviruses as well as endogenous retroelements. In contrast to these beneficial innate immune functions, recent studies have demonstrated that A3B and at least one other A3 enzyme deaminate genomic DNA and are responsible for cytosine-biased mutation patterns in many different human cancers (15–20). Key evidence includes positive correlations between A3B expression levels and genomic mutation loads and the intrinsic biochemical preference of the enzyme closely matching the observed cytosine mutation biases (i.e., C-to-T and C-to-G mutations occurring within 5′-TCA, TCG, and TCT trinucleotide contexts). Moreover, these signature mutations are sometimes found in strand-coordinated clusters termed kataegis, which can be coincident with sites of DNA rearrangement (21). Finally, there appears to be a mechanistic relationship between the antiviral response and cancer mutagenesis, as human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated tumor types (cervical, head and neck, and bladder cancers) often manifest the highest levels of A3B expression and global DNA cytosine mutation biases, A3B expression is induced specifically by HPV infection in relevant cell types (22), and the spectrum of PIK3CA activating mutations is biased toward an A3B deamination motif in HPV-positive head and neck tumors (23).

In this study, we set out to determine the relationship between PyV infection and the regulation of A3 family members. Using a relevant primary cell culture system, we demonstrated a unique and specific regulation of APOBEC3B by PyV and its encoded TAg. We also present evidence pointing to potential long-term effects of APOBEC-mediated deamination on PyV DNA genome composition and evolution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, virus growth, and lentivirus production.

Primary renal proximal tubule epithelial (RPTE) cells were expanded and maintained as described previously (24, 25). BKPyV Dunlop strain was grown in Vero cells, and titers were determined using an infectious-unit assay (26). RPTE cells were infected with BKPyV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5 infectious unit (IU)/cell as described previously (27). For TAg-expressing lentiviruses, JCPyV and MCPyV TAg cDNAs were subcloned from pBS-JT(Int-) (28) and pcDNA6.MCV.cLT206.V5 (Addgene), respectively, into lentivirus vector pLentiloxpuro (29). Lentiviruses expressing BKPyV TAg, JCPyV TAg, or MCPyV TAg were grown in 293T cells and transduced into RPTE cells as described previously (29).

Western blotting, RNA isolation, RT-qPCR, and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) deaminase assays.

Protein lysates were harvested at one or 3 days postinfection (dpi) or posttransduction, quantified, and immunoblotted as described previously (26). The anti-A3B antibody 5210-87-13 is a rabbit monoclonal antibody used at a dilution of 1:50 (30). This antibody recognizes both A3B and A3G; however, the two proteins can be distinguished by differential gel migration (30; this study). Mouse monoclonal antibody sc-136172 recognizing MCPyV-TAg was used at a dilution of 1:500 (Santa Cruz). JCPyV-TAg was recognized by pAb416 as described for BKPyV-TAg (26). Total RNA was harvested by removal of medium and resuspension in TRIzol (Thermo Fisher), and purification was done per the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was used to quantify A3 transcripts as described previously (22). DNA deaminase activity assays were implemented as described previously (22).

siRNA knockdown.

Nontargeting control and A3B-targeting ON-TARGET plus small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were purchased from Dharmacon (GE Healthcare). Each siRNA, at a concentration of 20 nM, was reverse transfected into RPTE cells as described previously (24). The cells were infected with BKPyV at 3 days posttransfection at an MOI of 0.5 IU/cell as described above. Total cell protein lysates were harvested, transferred, and probed for A3B, TAg, VP1 (26), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as described above. For viral DNA quantitation, low-molecular-weight DNA was purified and quantified using qPCR (29). Viral progeny were quantified using an infectious-unit assay (24).

Bioinformatic analyses.

Sequences from all available complete BK polyomavirus genomes (n = 302) were acquired from GenBank and aligned using Clustal Omega (31) to ensure that the homologous bases from each genome are in identical positions. Dinucleotide and trinucleotide motif enrichments for each aligned genome were calculated using Markov modeling as described by Ebrahimi and colleagues (32). Standard error was calculated and data were plotted using GraphPad Prism. Spearman's linear correlation coefficients of the enrichment between APOBEC target and product trinucleotides were calculated in the R statistical environment. Dinucleotide density was calculated across the BKPyV genome using 100-bp nonoverlapping windows. Smoothed fitted lines and 95% confidence intervals of these densities were calculated and plotted using the ggplot2 package in the R statistical environment.

RESULTS

BKPyV infection upregulates A3B specifically.

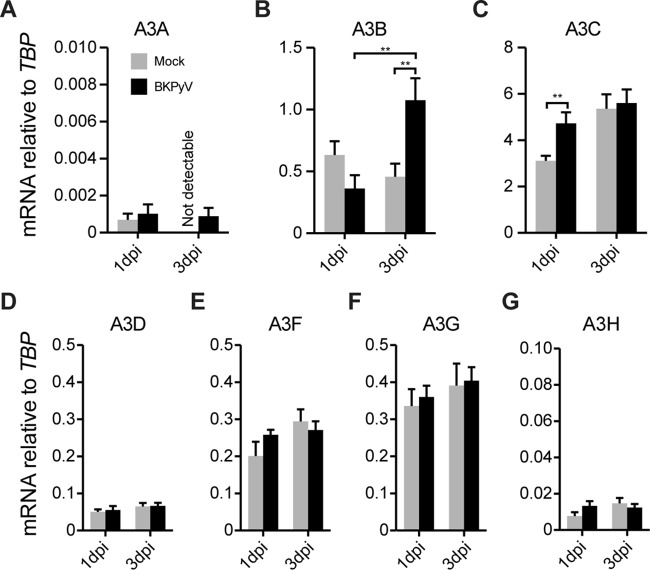

We first asked whether polyomaviruses modulate cellular A3 levels and activity since these viruses have oncogenic potential (33). Using BKPyV and an established primary renal proximal tubule epithelial (RPTE) cell culture system (24, 25), we determined whether virus infection alters A3 gene expression (Fig. 1). RPTE cells were infected with BKPyV at an MOI of 0.5 IU/cell, and total RNA was extracted 1 and 3 days postinfection (dpi) and subjected to RT-qPCR analyses (22). One day postinfection is an early time point when the input virus has just entered the nucleus (26), whereas 3 dpi represents a time when viral replication is robust (24). Among all A3 family members, only A3B expression changed significantly by BKPyV infection at 3 dpi (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

BKPyV infection upregulates A3B transcripts. RNA was harvested and purified from mock-infected or BKPyV-infected cells, and A3 mRNA levels were quantified by RT-qPCR. Histograms report mean A3 mRNA expression levels in mock- or BKPyV-infected RPTE cells in three independent experiments normalized to those of the housekeeping gene TBP. Error bars show standard deviations, and Student's t test was used to assess significance (**, P < 0.01). APOBEC1, APOBEC2, APOBEC4, and AID mRNAs were not detectable.

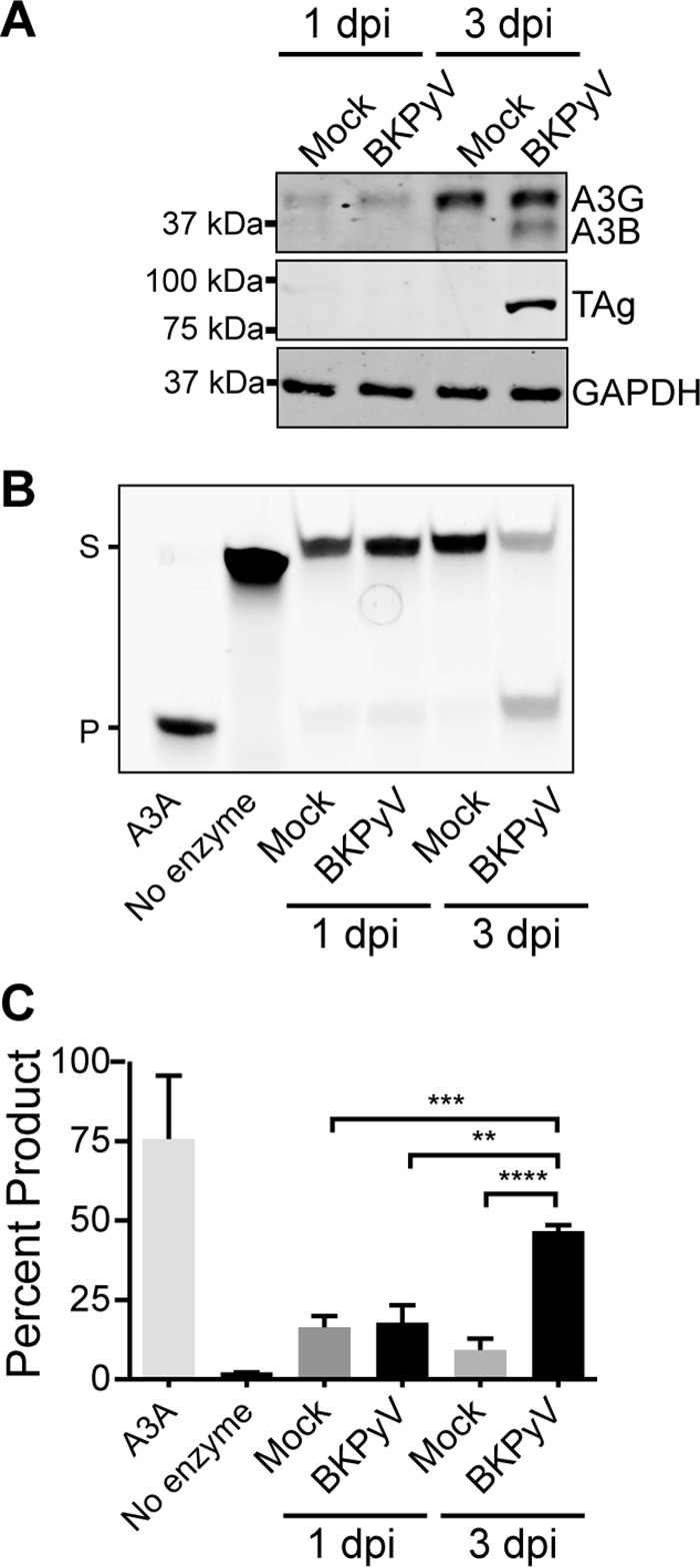

We then asked whether the observed increase in A3B mRNA also occurs at the protein level (Fig. 2A). Total cell lysates were immunoblotted for A3B, TAg, and GAPDH. Although the anti-A3B MAb recognized both A3B (lower band) and A3G (top band) (30), the immunoblots clearly show A3B protein upregulation by 3 dpi (Fig. 2A). It is notable that 3 dpi is around the time point that viral TAg becomes highly expressed (29). A3G protein levels are also upregulated at 3 dpi in both mock-infected and virus-infected cells, which could be due to a posttranscriptional regulatory process triggered by cellular growth.

FIG 2.

BKPyV infection increases A3B protein and cellular deaminase activity. (A) Total protein lysates from representative cells in Fig. 1 were immunoblotted for A3B (the antibody also recognizes A3G), TAg, and GAPDH. Shown are representative blots from three independent repeats. (B) Representative gel image of a DNA cytosine deaminase assay performed with cell extracts from mock- or BKPyV-infected cells as in panel A. Recombinant purified APOBEC3A was used as a positive control, and reaction buffer alone was used as a negative control. S, substrate; P, product. (C) The deaminated products were quantified by the Fiji gel analysis tool (http://fiji.sc/). Shown are combined results from three independent repeats. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

To determine whether increased A3B protein levels also correlate with elevated activity, we performed a series of DNA deaminase activity assays using whole-cell extracts and an ssDNA oligonucleotide containing a single TCA target motif (22). All APOBEC family members, except A3G, prefer this trinucleotide as a deamination target. A representative gel and quantification of 3 independent experiments are shown in Fig. 2B and C. C-to-U deamination, uracil excision, and mild hydroxide treatment combine to break the ssDNA at the site of deamination and result in a smaller, faster-migrating fragment. The positive control, purified A3A, converted nearly all of the substrate to product. In comparison, all mock-infected or 1-dpi RPTE cell extracts yielded only 5 to 10% product accumulation, whereas 3-dpi BKPyV-infected RPTE cell extracts showed ∼50% product accumulation. Thus, the increase in A3B mRNA and protein levels correlated with increases in measurable enzymatic activity that were similar and of significant magnitude in RPTE cell extracts.

Polyomavirus TAg is sufficient for A3B upregulation.

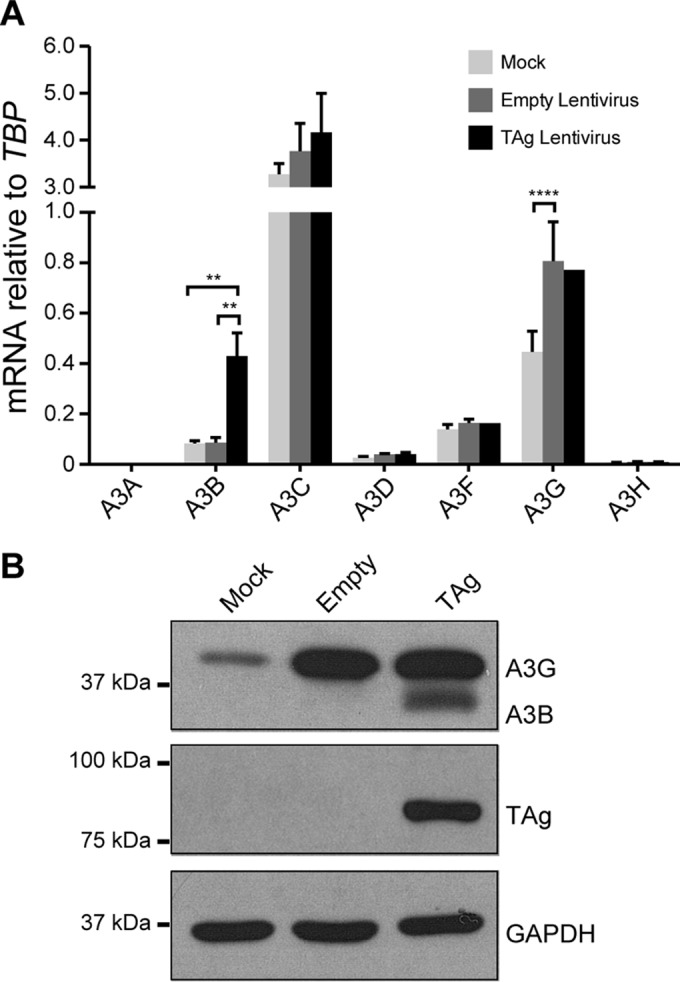

For high-risk HPV, the viral E6 oncoprotein alone is sufficient to trigger A3B upregulation (22). Therefore, we hypothesized that polyomavirus TAg may trigger a similarly specific response, since TAg and E6 share some overlapping functions. To test this idea, we expressed BKPyV TAg in RPTE cells using a previously reported lentivirus delivery system (27) and measured the A3 mRNA levels as for Fig. 1. Consistent with the BKPyV infection data, the expression of TAg increased A3B transcript levels specifically (Fig. 3A). As with the full virus, A3B upregulation also manifested at the protein level (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, as previously shown for HIV-1 infection of T lymphocytes (34), the lentiviral vector itself caused A3G induction, which was evident at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

PyV large T antigen is sufficient for A3B upregulation. RPTE cells were mock transduced, transduced with an empty lentivirus control, or transduced with a lentivirus expressing BKPyV TAg. A3 family member mRNA levels (A) and A3B protein levels (B) were examined as for Fig. 1 and 2, respectively. Note that A3A mRNA was detected but at too low a level to be graphed in panel A. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001.

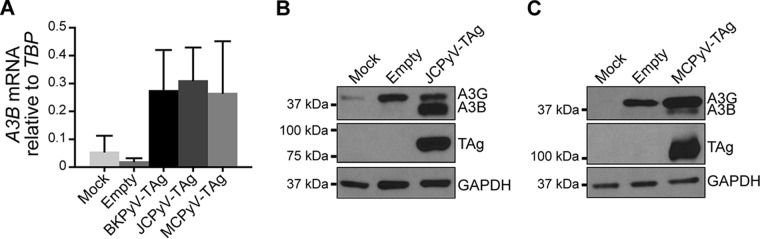

We then investigated whether A3B upregulation might be a general feature of the polyomavirus family. To address this point, we subcloned JCPyV and MCPyV TAg cDNA into the lentiviral expression vector pLentiloxpuro as was done for BKPyV TAg (29). Similar to the case with BKPyV TAg, we found by both RT-qPCR (Fig. 4A) and immunoblotting (Fig. 4B and C) that both JCPyV and MCPyV TAg induced A3B levels. Interestingly, the magnitudes of A3B induction at the mRNA level were similar, whereas the magnitudes at the protein level were considerably more variable, with JCPyV causing the highest level of induction (Fig. 2 to 4). The molecular explanation for this difference is not clear at this time, but the data suggest that the different PyV TAg proteins may impact A3B regulation differentially at multiple levels.

FIG 4.

Other human PyV large T antigens also upregulate A3B. RPTE cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing JVPyV or MCPyV Tag, and A3B mRNA and protein levels were determined by RT-qPCR (A) and immunoblotting (B and C), respectively, as in Fig. 3.

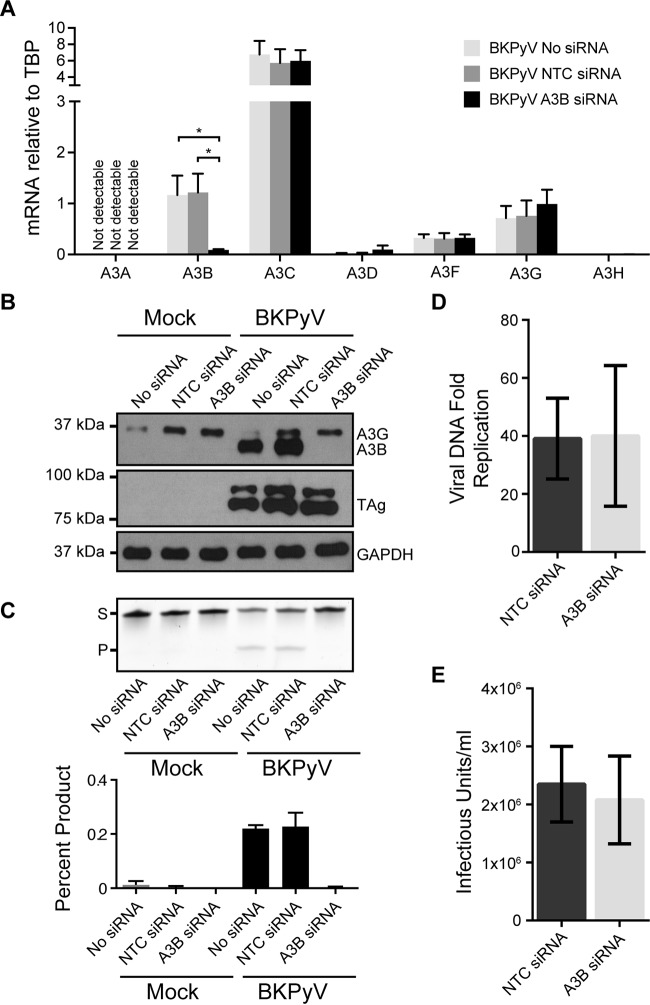

A3B is not required for productive BKPyV infection.

Next, we investigated whether upregulated A3B impacts BKPyV productive infection. To do this, we used siRNA to specifically knock down A3B in RPTE cells and assessed the effects of the knockdown on both cellular deaminase activity and viral life cycle. The knockdown of A3B was robust and specific, as evidenced by RT-qPCR and immunoblot data (Fig. 5A and B, respectively). A3B siRNA completely abolished the cellular deaminase activity, further confirming that the increased deaminase activity observed in BKPyV-infected cells originated solely from A3B upregulation (Fig. 5C). The specific depletion of A3B, however, did not affect viral TAg expression (Fig. 5B), viral DNA replication (Fig. 5D), or production of infectious viral progeny (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these data suggest that A3B is not necessary for short-term acute BKPyV productive infection.

FIG 5.

Knockdown of A3B eliminates deaminase activity during BKPyV infection but does not affect BKPyV lytic infection. Cells were left untreated or treated with nontargeting control (NTC) siRNA or A3B-targeting siRNA for 3 days, followed by mock infection or infection with BKPyV for 3 days. (A) A3 family member mRNA levels were determined as for Fig. 1. Shown are combined results from three independent experiments with infected cells. (B) Total protein lysates were immunoblotted for A3B, TAg, and GAPDH. Shown is a representative result from three independent repeats. (C) Representative gel image and quantitation of a DNA cytosine deaminase assay (as for Fig. 2) performed with cell extracts as for panel B. (D and E) Bar graphs of BKPyV viral DNA fold replication (D) and viral infectious units (E) produced from infected cells treated with NTC or A3B-targeting siRNA. Shown are combined results from three independent repeats.

BKPyV genomes display A3B-mediated mutation signatures.

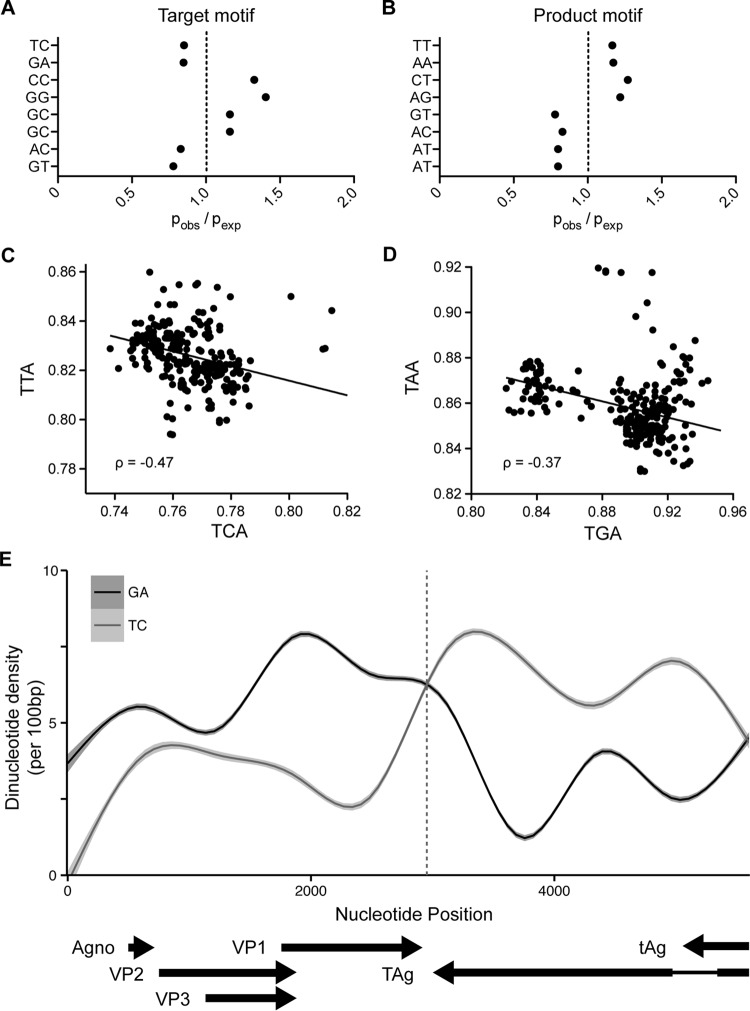

To address whether A3B upregulation by BKPyV TAg has had an impact on BK polyomavirus genome composition over an evolutionary time frame, we acquired and analyzed all available BKPyV complete genomes from GenBank (n = 302). We then calculated the enrichment of all dinucleotide motifs using the ratio of observed dinucleotides versus expected determined by Markov modeling and then focused on dinucleotides containing 3′ cytosines on the positive or negative strand (NC or GN, respectively) that can be targeted by APOBEC family member deamination and the dinucleotide product that would be produced upon deamination and replication of the viral genome (NT or AN). This analysis revealed an underrepresentation of TC:GA dinucleotides and an overrepresentation of TT:AA dinucleotides, which reflects the preferred deamination target of most APOBEC3 family members, including A3B, and the products of deamination without repair, respectively (Fig. 6A and B). Targets and their respective products of deamination by other APOBEC family members, such as A3G (CC:GG) or AID (RC:GY), were not observed to be distinctly depleted or enriched.

FIG 6.

Evidence for APOBEC mutagenesis on the BKPyV polyomavirus genome. (A) Over- and underrepresentation with standard errors of potential APOBEC-targeted cytosine dinucleotides in the BKPyV genome. (B) Over- and underrepresentation of dinucleotides produced by the deamination of the target dinucleotides in panel A. (C and D) Scatter plots and best-fit lines representing the linear correlations between A3B preferred target and the respective product trinucleotides TCA/TTA (C) and TGA/TAA (D). (E) Line graph of TC/GA dinucleotide density across the BKPyV genome with viral genes and transcription direction annotated at the bottom.

We next looked at the linear correlation between the A3B strongly preferred TCA:TGA trinucleotide to see if the reduction of specific target motifs in each genome directly correlated with the enrichment of product trinucleotides independently of spontaneous deamination of methylcytosines that would reduce NCG motifs, which are known to be underrepresented in polyomavirus genomes (35). We observed strong negative linear correlations for both TCA-TTA and TGA-TAA trinucleotide pairs, indicating that as one motif is depleted the other increases, strongly supporting a model in which deamination and mutation by A3B has shaped BKPyV evolution (Fig. 6C and D). Finally, we observed a clear inverse relationship between TC and GA dinucleotide density that corresponds to either the deamination of the nontranscribed strand of the viral genome during transcription or the lagging strand during replication in the BKPyV genome (Fig. 6E). The latter is supported by several recent studies investigating the nature of APOBEC-mediated mutations in various cancers (36–39). However, considering the gene organization of the BKPyV genome and the bidirectional nature of its genome replication, we cannot at this time definitively determine whether transcription or lagging-strand DNA replication predisposes to more viral genomic mutation.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we report here that polyomavirus infection specifically upregulates A3B expression and activity and that the viral TAg is sufficient to mediate this response. To our knowledge, this is the first work to show a direct link between polyomavirus infection and A3B upregulation. Our results also reveal that TAgs from multiple human PyVs are capable of upregulating the expression and activity of A3B. Given the fact that other small DNA viruses, such as HPV, also specifically increase A3B (22), these findings suggest that A3B upregulation may be a conserved response to small DNA tumor virus infections.

Using siRNA knockdown, we showed that A3B is indeed responsible for the increased cellular deaminase activity in BKPyV-infected cells (Fig. 5C). However, A3B expression does not facilitate or impair productive BKPyV infection, as neither viral DNA replication nor viral progeny production was affected by A3B depletion (Fig. 5D and E). It is possible that since our assays only measured initial rounds of viral infection, any subtle restrictive effects of A3B may have been missed. Additional investigation of long-term A3B depletion will be necessary to assess the functional significance of A3B upregulation over an evolutionary time span.

Although we did not detect immediate viral infection or replication defects associated with A3B knockdown, our computational analysis of all publicly available BKPyV genomes revealed that BKPyV genomes are depleted of the A3B preferred target dinucleotides (TCA:TGA), with a concomitant overrepresentation of the corresponding deamination products (TTA:TAA) (Fig. 6A to D). These results suggest that the functional increase in A3B activity has exerted long-term evolutionary pressure on the nucleotide composition of the viral genomic DNA. It is unclear whether the virus directly induces the A3B response to such a level as to avoid restriction while generating additional genetic diversity for better fitness as has been observed in HIV-1 (40, 41). Our data are also consistent with recent reports that point to possible roles of A3 enzymes during HPV evolution (42). Interestingly, we also identified a strong asymmetry in the abundance TC or its reverse complement GA that corresponds to the direction of both transcription and viral genomic DNA lagging-strand replication. In support of this potential mechanistic relationship, several groups recently reported that APOBEC-mediated mutation of cancer (and model) genomes is preferentially linked to the lagging strand of DNA replication, where more ssDNA intermediates would be expected to occur (36–39).

A range of A3B transcriptional regulation mechanisms in both viral and nonviral cancers have been reported (22, 30). It has been postulated that E6 protein from high-risk HPV derepresses A3B gene transcription via p53 inactivation (22). From our results, this is an unlikely mechanism for polyomavirus-mediated upregulation of A3B, since MCPyV TAg does not bind p53 (7) yet it clearly triggers an increase in A3B level (Fig. 4C). Another study reported that HPV E7 protein, which is known to inhibit Rb function, is required for upregulation of both A3A and A3B in HPV-positive normal human immortalized keratinocyte cells (43). In multiple cancer cell lines not associated with virus infection and for which A3B overexpression is observed, the protein kinase C (PKC)/noncanonical NF-κB signaling pathway has been shown to be necessary for A3B induction (30). It is possible that each of these studies reveals separate pathways regulating the expression and activity of A3B or that may be connected through yet-to-be-determined mechanisms. Future investigation on polyomavirus TAg will be valuable to determine if a direct or indirect function of the TAg is responsible for A3B upregulation.

Finally, it is possible that TAg-mediated upregulation of A3B may also lead to host genomic DNA mutations that contribute to carcinogenesis. Several recent studies have implicated BKPyV seropositivity with the development of urothelial cancers in immunocompromised patients (4). Polyomavirus-mediated upregulation of A3B may contribute to carcinogenesis in these patients much as HPV-mediated upregulation of A3B likely contributes to the tumor evolution and the dominant APOBEC signature mutation spectra observed in cervical and HPV-positive head and neck cancers (22, 23). Future studies on the host genomic DNA mutations occurring in cells infected with BKPyV and tumors expressing TAg will address this issue. If this contribution is confirmed, it will add to the already diverse functions of TAg for its oncogenic potential.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Richard Frisque for the JCPyV pBS-JCT(Int-) plasmid, Ellen Cahir-McFarland for thoughtful comments, and James DeCaprio for MCPyV reagents.

Salary support for G.J.S. was provided by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (grant 00039202). R.S.H. is an Investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Jiang lab contributions were supported in part by the UAB Department of Microbiology start-up fund, AHA Scientist Development grant 15SDG25680061, and NIH grant R01AI123162.

R.S.H. is a cofounder, shareholder, and consultant of ApoGen Biotechnologies Inc. A research project in the Harris laboratory is supported by Biogen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Doerries K. 2006. Human polyomavirus JC and BK persistent infection. Adv Exp Med Biol 577:102–116. doi: 10.1007/0-387-32957-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeCaprio JA, Garcea RL. 2013. A cornucopia of human polyomaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:264–276. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett SM, Broekema NM, Imperiale MJ. 2012. BK polyomavirus: emerging pathogen. Microbes Infect 14:672–683. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papadimitriou JC, Randhawa P, Rinaldo CH, Drachenberg CB, Alexiev B, Hirsch HH. 2016. BK polyomavirus infection and renourinary tumorigenesis. Am J Transplant 16:398–406. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wollebo HS, White MK, Gordon J, Berger JR, Khalili K. 2015. Persistence and pathogenesis of the neurotropic polyomavirus JC. Ann Neurol 77:560–570. doi: 10.1002/ana.24371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang Y, Moore PS. 2012. Merkel cell carcinoma: a virus-induced human cancer. Annu Rev Pathol 7:123–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng J, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Paulson KG, Nghiem P, DeCaprio JA. 2013. Merkel cell polyomavirus large T antigen has growth-promoting and inhibitory activities. J Virol 87:6118–6126. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00385-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giacobbi NS, Gupta T, Coxon AT, Pipas JM. 2015. Polyomavirus T antigens activate an antiviral state. Virology 476:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abend JR, Low JA, Imperiale MJ. 2010. Global effects of BKV infection on gene expression in human primary kidney epithelial cells. Virology 397:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yogo Y, Sugimoto C, Zhong S, Homma Y. 2009. Evolution of the BK polyomavirus: epidemiological, anthropological and clinical implications. Rev Med Virol 19:185–199. doi: 10.1002/rmv.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gjoerup O, Chang Y. 2010. Update on human polyomaviruses and cancer. Adv Cancer Res 106:1–51. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(10)06001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wendzicki JA, Moore PS, Chang Y. 2015. Large T and small T antigens of Merkel cell polyomavirus. Curr Opin Virol 11:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris RS, Dudley JP. 2015. APOBECs and virus restriction. Virology 479-480:131–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieira VC, Soares MA. 2013. The role of cytidine deaminases on innate immune responses against human viral infections. Biomed Res Int 2013:683095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinohara M, Io K, Shindo K, Matsui M, Sakamoto T, Tada K, Kobayashi M, Kadowaki N, Takaori-Kondo A. 2012. APOBEC3B can impair genomic stability by inducing base substitutions in genomic DNA in human cells. Sci Rep 2:806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burns MB, Lackey L, Carpenter MA, Rathore A, Land AM, Leonard B, Refsland EW, Kotandeniya D, Tretyakova N, Nikas JB, Yee D, Temiz NA, Donohue DE, McDougle RM, Brown WL, Law EK, Harris RS. 2013. APOBEC3B is an enzymatic source of mutation in breast cancer. Nature 494:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature11881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts SA, Lawrence MS, Klimczak LJ, Grimm SA, Fargo D, Stojanov P, Kiezun A, Kryukov GV, Carter SL, Saksena G, Harris S, Shah RR, Resnick MA, Getz G, Gordenin DA. 2013. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat Genet 45:970–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burns MB, Temiz NA, Harris RS. 2013. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet 45:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Alexandrov LB, Petljak M, Butler AP, Bolli N, Davies HR, Knappskog S, Martin S, Papaemmanuil E, Ramakrishna M, Shlien A, Simonic I, Xue Y, Tyler-Smith C, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. 2014. Association of a germline copy number polymorphism of APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B with burden of putative APOBEC-dependent mutations in breast cancer. Nat Genet 46:487–491. doi: 10.1038/ng.2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan K, Roberts SA, Klimczak LJ, Sterling JF, Saini N, Malc EP, Kim J, Kwiatkowski DJ, Fargo DC, Mieczkowski PA, Getz G, Gordenin DA. 2015. An APOBEC3A hypermutation signature is distinguishable from the signature of background mutagenesis by APOBEC3B in human cancers. Nat Genet 47:1067–1072. doi: 10.1038/ng.3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov LB, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Greenman CD, Raine K, Jones D, Hinton J, Marshall J, Stebbings LA, Menzies A, Martin S, Leung K, Chen L, Leroy C, Ramakrishna M, Rance R, Lau KW, Mudie LJ, Varela I, McBride DJ, Bignell GR, Cooke SL, Shlien A, Gamble J, Whitmore I, Maddison M, Tarpey PS, Davies HR, Papaemmanuil E, Stephens PJ, McLaren S, Butler AP, Teague JW, Jonsson G, Garber JE, Silver D, Miron P, Fatima A, Boyault S, Langerod A, Tutt A, Martens JW, Aparicio SA, Borg A, Salomon AV, Thomas G, Borresen-Dale AL, Richardson AL, Neuberger MS, Futreal PA, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR, Breast Cancer Working Group of the International Cancer Genome Consortium. 2012. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell 149:979–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vieira VC, Leonard B, White EA, Starrett GJ, Temiz NA, Lorenz LD, Lee D, Soares MA, Lambert PF, Howley PM, Harris RS. 2014. Human papillomavirus E6 triggers upregulation of the antiviral and cancer genomic DNA deaminase APOBEC3B. mBio 5:e02234-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02234-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson S, Chakravarthy A, Su X, Boshoff C, Fenton TR. 2014. APOBEC-mediated cytosine deamination links PIK3CA helical domain mutations to human papillomavirus-driven tumor development. Cell Rep 7:1833–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang M, Zhao L, Gamez M, Imperiale MJ. 2012. Roles of ATM and ATR-mediated DNA damage responses during lytic BK polyomavirus infection. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002898. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low J, Humes HD, Szczypka M, Imperiale M. 2004. BKV and SV40 infection of human kidney tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Virology 323:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang M, Abend JR, Tsai B, Imperiale MJ. 2009. Early events during BK virus entry and disassembly. J Virol 83:1350–1358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02169-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verhalen B, Justice JL, Imperiale MJ, Jiang M. 2015. Viral DNA replication-dependent DNA damage response activation during BK polyomavirus infection. J Virol 89:5032–5039. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03650-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollag B, Mackeen PC, Frisque RJ. 1996. Purified JC virus T antigen derived from insect cells preferentially interacts with binding site II of the viral core origin under replication conditions. Virology 218:81–93. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang M, Entezami P, Gamez M, Stamminger T, Imperiale MJ. 2011. Functional reorganization of promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies during BK virus infection. mBio 2:e00281-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00281-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard B, McCann JL, Starrett GJ, Kosyakovsky L, Luengas EM, Molan AM, Burns MB, McDougle RM, Parker PJ, Brown WL, Harris RS. 29 September 2015. The PKC/NF-kappaB signaling pathway induces APOBEC3B expression in multiple human cancers. Cancer Res doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2171-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebrahimi D, Anwar F, Davenport MP. 2011. APOBEC3 has not left an evolutionary footprint on the HIV-1 genome. J Virol 85:9139–9146. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00658-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moens U, Rasheed K, Abdulsalam I, Sveinbjornsson B. 2015. The role of Merkel cell polyomavirus and other human polyomaviruses in emerging hallmarks of cancer. Viruses 7:1871–1901. doi: 10.3390/v7041871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hultquist JF, Lengyel JA, Refsland EW, LaRue RS, Lackey L, Brown WL, Harris RS. 2011. Human and rhesus APOBEC3D, APOBEC3F, APOBEC3G, and APOBEC3H demonstrate a conserved capacity to restrict Vif-deficient HIV-1. J Virol 85:11220–11234. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05238-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoelzer K, Shackelton LA, Parrish CR. 2008. Presence and role of cytosine methylation in DNA viruses of animals. Nucleic Acids Res 36:2825–2837. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haradhvala NJ, Polak P, Stojanov P, Covington KR, Shinbrot E, Hess JM, Rheinbay E, Kim J, Maruvka YE, Braunstein LZ, Kamburov A, Hanawalt PC, Wheeler DA, Koren A, Lawrence MS, Getz G. 2016. Mutational strand asymmetries in cancer genomes reveal mechanisms of DNA damage and repair. Cell 164:538–549. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoopes JI, Cortez LM, Mertz TM, Malc EP, Mieczkowski PA, Roberts SA. 2016. APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B preferentially deaminate the lagging strand template during DNA replication. Cell Rep 14:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seplyarskiy VB, Soldatov RA, Popadin KY, Antonarakis SE, Bazykin GA, Nikolaev SI. 2016. APOBEC-induced mutations in human cancers are strongly enriched on the lagging DNA strand during replication. Genome Res 26:174–182. doi: 10.1101/gr.197046.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhagwat AS, Hao W, Townes JP, Lee H, Tang H, Foster PL. 2016. Strand-biased cytosine deamination at the replication fork causes cytosine to thymine mutations in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:2176–2181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522325113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haché G, Mansky LM, Harris RS. 2006. Human APOBEC3 proteins, retrovirus restriction, and HIV drug resistance. AIDS Rev 8:148–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monajemi M, Woodworth CF, Benkaroun J, Grant M, Larijani M. 2012. Emerging complexities of APOBEC3G action on immunity and viral fitness during HIV infection and treatment. Retrovirology 9:35. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warren CJ, Doorslaer KV, Pandey A, Espinosa JM, Pyeon D. 2015. Role of the host restriction factor APOBEC3 on papillomavirus evolution. Virus Evol 1:vev015. doi: 10.1093/ve/vev015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warren CJ, Xu T, Guo K, Griffin LM, Westrich JA, Lee D, Lambert PF, Santiago ML, Pyeon D. 2015. APOBEC3A functions as a restriction factor of human papillomavirus. J Virol 89:688–702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02383-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]