ABSTRACT

The pathogenic Old World arenavirus Lassa virus (LASV) causes a severe hemorrhagic fever with a high rate of mortality in humans. Several LASV receptors, including dystroglycan (DG), TAM receptor tyrosine kinases, and C-type lectins, have been identified, suggesting complex receptor use. Upon receptor binding, LASV enters the host cell via an unknown clathrin- and dynamin-independent pathway that delivers the virus to late endosomes, where fusion occurs. Here we investigated the mechanisms underlying LASV endocytosis in human cells in the context of productive arenavirus infection, using recombinant lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (rLCMV) expressing the LASV glycoprotein (rLCMV-LASVGP). We found that rLCMV-LASVGP entered human epithelial cells via DG using a macropinocytosis-related pathway independently of alternative receptors. Dystroglycan-mediated entry of rLCMV-LASVGP required sodium hydrogen exchangers, actin, and the GTPase Cdc42 and its downstream targets, p21-activating kinase-1 (PAK1) and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-Wasp). Unlike other viruses that enter cells via macropinocytosis, rLCMV-LASVGP entry did not induce overt changes in cellular morphology and hardly affected actin dynamics or fluid uptake. Screening of kinase inhibitors identified protein kinase C, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and the receptor tyrosine kinase human hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR) to be regulators of rLCMV-LASVGP entry. The HGFR inhibitor EMD 1214063, a candidate anticancer drug, showed antiviral activity against rLCMV-LASVGP at the level of entry. When combined with ribavirin, which is currently used to treat human arenavirus infection, EMD 1214063 showed additive antiviral effects. In sum, our study reveals that DG can link LASV to an unusual pathway of macropinocytosis that causes only minimal perturbation of the host cell and identifies cellular kinases to be possible novel targets for therapeutic intervention.

IMPORTANCE Lassa virus (LASV) causes several hundred thousand infections per year in Western Africa, with the mortality rate among hospitalized patients being high. The current lack of a vaccine and the limited therapeutic options at hand make the development of new drugs against LASV a high priority. In the present study, we uncover that LASV entry into human cells via its major receptor, dystroglycan, involves an unusual pathway of macropinocytosis and define a set of cellular factors implicated in the regulation of LASV entry. A screen of kinase inhibitors revealed HGFR to be a possible candidate target for antiviral drugs against LASV. An HGFR candidate inhibitor currently being evaluated for cancer treatment showed potent antiviral activity and additive drug effects with ribavirin, which is used in the clinic to treat human LASV infection. In sum, our study reveals novel fundamental aspects of the LASV-host cell interaction and highlights a possible candidate drug target for therapeutic intervention.

INTRODUCTION

The Old World arenavirus Lassa virus (LASV) is the causative agent of a severe viral hemorrhagic fever with a high rate of mortality in humans (1, 2). Carried in nature by persistent infection of its reservoir host, Mastomys natalensis, LASV is currently endemic in most of Western Africa, where it causes several hundred thousand infections per year and thousands of deaths (1). Recent studies on the origin and evolution of LASV revealed that human infection mainly results from reservoir-to-human transmission, whereas human-to-human infection is rare (3). The exact mechanisms of zoonotic transmission of LASV are not well established, but it likely occurs via inhalation of contaminated aerosolized rodent excreta, ingestion of contaminated food, or direct contact with infected rodents (1). Due to its transmissibility via aerosol (4) and high lethality, LASV has been characterized as a category A agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5). There is no licensed vaccine, and the only treatment at hand is the off-label use of ribavirin (Rib), which reduces mortality when delivered early in infection (6) but often causes severe side effects. Novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of Lassa fever are therefore urgently needed.

Lassa virus is an enveloped negative-strand RNA virus with a nonlytic life cycle restricted to the cytoplasm (7). The viral genome is comprised of two RNA segments that code for two proteins each, using an ambisense coding strategy. The small (S) RNA segment encodes the envelope glycoprotein precursor (GPC) and the nucleoprotein (NP), and the L segment codes for the matrix protein (Z) as well as the viral polymerase (L) (8). The GPC is synthesized as a single polypeptide and undergoes processing by the cellular proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin isozyme-1 (SKI-1)/site-1 protease (S1P), yielding the N-terminal GP1 and the transmembrane GP2 (9). GP1 binds to cellular receptors, whereas GP2 mediates viral fusion and structurally resembles class I viral fusion proteins (10). Despite its virulence in humans and primates, LASV infection of mammalian cells causes no overt cytopathic effects and results in only minimal perturbation of host cell function, allowing the virus to establish persistence in mammalian cells in vitro and in its reservoir host in vivo.

Fatal LASV infection in humans is characterized by rapid viral multiplication accompanied by progressive signs and symptoms of shock (2). A factor highly predictive of the disease outcome is the viral load, indicating a close competition between viral spread and replication and the patient's immune system (11). Drugs targeting specific steps of the viral life cycle may reduce the multiplication and spread of the virus, providing the patient's immune system a window of opportunity to develop antiviral immune responses. A major challenge for the development of antiviral agents that directly act against LASV is the limited available structural information on the pathogen. Like all viruses, LASV critically depends on the molecular machinery of the host cell for its multiplication. Host cell receptor binding and subsequent viral entry are the first and most fundamental steps in viral transmission and represent key determinants of the host range, tissue tropism, and, hence, disease potential of a virus (12–14). Targeting of viral entry appears to be a promising strategy for therapeutic intervention, as it allows the pathogen to be blocked before it can take control over the host cell. The goal of our study was identification of the cellular factors required for productive LASV entry and evaluation of those factors as possible targets for therapeutic antiviral intervention.

The first cellular receptor for LASV was identified to be dystroglycan (DG), a ubiquitously expressed and highly conserved receptor for extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (15). Expressed in most developing and adult tissues in cells adjoining basement membranes, DG provides a molecular link between the ECM and the actin-based cytoskeleton (16). Initially synthesized as a single precursor polypeptide, DG core protein is processed into the N-terminal α-DG and the transmembrane β-DG (16). Binding of LASV and ECM proteins to α-DG critically depends on posttranslational modification by the glycosyltransferase LARGE, which adds 3-xylose-α1,3-glucuronic acid-β1 copolymer polysaccharides to the α-DG moiety in a tissue-specific manner (17–22). A recent genome-wide haploid screen revealed that the molecular mechanisms of receptor recognition of LASV strikingly mimic those of receptor recognition of host-derived ECM proteins (23). More recently, the Tyro3/Axl/Mer (TAM) receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) Axl and Tyro3/Dtk, as well as the C-type lectins DC-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN) and LSECtin, have been identified to be candidate LASV receptors (24, 25). The coexpression of DG with TAM receptors on many human cell types implicated in LASV infection (26) suggests complex receptor use.

Upon receptor binding, LASV enters the host cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis with subsequent transport to late endosomal compartments, where fusion occurs at low pH (27, 28). An initial report described LASV cell entry via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) (29), whereas subsequent studies suggested the involvement of an unknown clathrin- and dynamin-independent pathway (30, 31). Recent genome-wide RNA interference (RNAi) silencing screens identified host factors involved in the multiplication of the prototypic Old World arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) (32). Among the hits was a sodium hydrogen exchanger, NHE, a cellular factor involved in macropinocytosis (33). In a follow-up study, de la Torre and colleagues validated NHE to be the entry factor for arenaviruses and demonstrated that LCMV can enter cells via a pathway showing hallmarks of macropinocytosis (34), providing a first link between arenavirus entry and macropinocytosis. At the late endosome, LASV undergoes a receptor switch and engages the late endosomal/lysosomal resident protein LAMP1 for efficient fusion (35). The dependence of LASV on late endosomal entry factors represents an interesting analogy to filoviruses like Ebola virus, whose fusion likewise depends on late endosomal proteins like Niemann-Pick C1 (36). In our present study, we extended previous findings investigating the pathway underlying LASV endocytosis into human cells relevant for zoonotic transmission. We provide evidence that DG is able to link LASV to an unusual pathway of macropinocytosis that causes only minimal perturbation of the host cell and identify the cellular factors involved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents.

Mouse anti-LCMV NP monoclonal antibody (MAb) 113 has been described previously (37). Anti-α-DG (mouse IgM) MAb IIH6 was provided by Kevin Campbell (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Iowa). Purified goat anti-human Axl IgG polyclonal antibody (pAb), anti-hDtk/Tyro3 MAb 96201, and anti-DC-SIGN MAb 120507 were from R&D Systems. Polyclonal guinea pig anti-LCMV serum was provided by Juan Carlos de la Torre (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). Polyclonal mouse serum with antibodies to New World arenaviruses was provided by the Specials Pathogen Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA). Mouse MAb to influenza A virus (IAV) NP was a gift from Silke Stertz (Institute of Medical Virology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland). Polyclonal rabbit antibodies to green fluorescent protein (GFP) and human hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-Met) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Abcam, respectively. Other MAbs included mouse IgG anti-β-DG MAb 8D5 (Novocastra) and mouse anti-α-tubulin MAb B-5-1-2 (Sigma). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgG, goat anti-mouse IgM, and rabbit anti-goat IgG were from Dako. Rhodamine red-X-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-guinea pig IgG were from Jackson ImmunoResearch. The nuclear dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and phalloidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). The CellTiter-Glo assay system was obtained from Promega (Madison WI). Dextran (10 kDa) conjugated to FITC was from Sigma. Further inhibitors included dynasore, dyngo-4a, and pitstop-2 (Ascent Scientific); pirl1 (Chembridge); wiskostatin (Enzo); and CT04, CAS869, NSC237766, wortmannin, blebbistatin, chlorpromazine, cytochalasin D, 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA), IPA-3, jasplakinolide, latrunculin A, ML7, ribavirin, and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) (Sigma). The kinase inhibitor library was from Enzo Life Science (catalog no. BML-2832-0100), and the library was supplemented with the following inhibitors: the human hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR) inhibitors EMD 1214063 and PHA-665752 (Selleckchem), the epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors CAS879127-07-8 and gefitinib (Sigma), the ErbB3 inhibitor AZD 8931 (Sigma), and the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor calphostin C (Sigma). For screening, the compounds were used at 10 μM. Exceptions were PKC-412, GF 109203X, Ro 31-8220, KN-93, and rottlerin, which were used at 5 μM, and AG-879 and calphostin C, which were used at 2 μM.

Cells and viruses.

Human lung carcinoma alveolar epithelial (A549) cells, cells of the human lung epithelial cell line WI-26VA4, and human epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma (Caco-2) cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM)–10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS) supplemented with glutamine and penicillin-streptomycin. Caco-2 cells were cultured on collagen-coated tissue culture plates. Primary human bronchial epithelial cells isolated from human bronchi were purchased from ScienCell (catalog no. 3210). Freshly thawed cells were seeded in a poly-l-lysine (2 μg/cm2)-coated T-75 tissue culture flask at a density of 5,000 cells/cm2 and cultured in bronchial epithelial cell medium from ScienCell (catalog no. 3211) following the supplier's instructions. For subculture, cells at >90% confluence were detached with ScienCell trypsin-EDTA solution adapted to minimize cell damage. Cells were subcultured for a maximum of 5 passages. For infection studies, cells were seeded in poly-l-lysine-coated M96 tissue culture plates at 20,000 cells/cm2, and experiments were performed after 2 to 3 days, when the cells had reached >90% confluence.

The generation, growth, and purification of recombinant lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (rLCMV) expressing the LASV glycoprotein (rLCMV-LASVGP) and rLCMV expressing the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus (rLCMV-VSVG) have been described elsewhere (30, 38). According to the institutional biosafety guidelines of the Lausanne University Hospital, the chimera rLCMV-LASVGP has been classified as a biosafety level 2 (BSL2) pathogen for use in cell culture. The Junin virus (JUNV) Candid 1 vaccine strain was provided by Michael Buchmeier. Retroviral pseudotypes expressing the glycoprotein of Amapari virus (AMPV) and an enhanced GFP (EGFP) reporter were produced as described previously (39). Recombinant human adenovirus (AdV) serotype 5 (Ad5) expressing EGFP has been described previously (40). Recombinant vaccinia virus (VACV) strain MR expressing EGFP (41) was provided by Jason Mercer (MRC-Laboratory for Molecular Cell Biology, University College London, London, United Kingdom) and was produced as mature virus (MV) (41). The IAV strain A/WSN/33 was a gift from Silke Stertz (Institute of Medical Virology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland).

Polarized epithelial monolayers.

Polarized A549 cell monolayers were established as described by Lutschg et al. (42). Briefly, A549 cells grown under subconfluent conditions were trypsinized and detached, and single-cell suspensions were prepared. The cells were then seeded onto Transwell cell culture inserts (pore size, 3 μm; 12-well format; catalog no. 353292; BD Bioscience) at 150% of the density of the subconfluent cell cultures on plastic. After 2 days, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured at the air-liquid interface with medium added only to the bottom, basolateral chamber (250 μl/chamber) for 9 days. Caco-2 cells were seeded at 120% of the density of the subconfluent cell cultures on plastic onto Transwell cell culture inserts. The cells were cultured for 4 to 5 days with medium added to both the apical and the basolateral chambers (250 μl/chamber) as described previously (43). The integrity of the polarized monolayer was validated by colloidal dye transport. To this end, 10-kDa dextran–FITC was added to the apical chamber at a concentration of 50 μg/ml, and the cells were incubated for 30 min. Diffusion through the monolayer was assessed by monitoring the concentration of the colloidal dye in the apical and basolateral chambers over time by sampling and detection in a Berthold microplate fluorescence reader. The apparent permeability (Permapp, in square centimeters per second) was calculated as follows: Permapp = (dq/dt) × [1/(A × C0)]. The term dq/dt represents the transport rate (in micrograms per second), where q is the amount of dye in micrograms and t is time; C0 is the starting concentration in the apical chamber (in micrograms per milliliter); and A is the surface area of the membrane (in square centimeters) (42).

Virus infections.

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and grown into confluent monolayers in 16 to 20 h. The cells were treated with the drugs as detailed below for the specific experiments, followed by infection with the viruses indicated below at the defined multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 1 h at 37°C. Unbound virus was removed, the cells were washed twice with DMEM, and fresh medium was added. Infection of rLCMV-LASVGP, rLCMV-VSVG, and LCMV clone 13 was quantified by detection of LCMV NP by an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) with MAb 113 as described previously (44). The cell entry kinetics of rLCMV-LASV were determined as described previously (30). Blocking of infection with specific antibodies was done as reported elsewhere (18). Infection with IAV was detected as reported previously (45). For the detection of JUNV Candid 1 infection, cells were stained with mouse hyperimmune serum against New World arenaviruses (1:500) combined with an FITC-labeled secondary antibody. Retroviral pseudotypes were detected by staining for the EGFP reporter as described previously (39).

Immunoblotting.

For immunoblotting, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. After the membranes were blocked in 3% (wt/vol) skim milk in PBS, they were incubated with 1 to 10 μg/ml primary antibody in 3% (wt/vol) skim milk in PBS overnight at 4°C. After several washes in PBS with 0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 20 (PBST), secondary antibodies coupled to HRP were applied 1:5,000 in PBST for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were developed by chemiluminescence using a LiteABlot kit (EuroClone). Signals were acquired by an ImageQuant LAS 4000Mini imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) or by exposure to X-ray films. Quantification of the Western blots was performed with ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

RNAi.

The depletion of HGFR by RNA interference (RNAi) was performed as described previously (31) using a specific HGFR-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA; 5′-CGA GAU GAA UGU GAA UAU GAA-3′; Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland). As a control for unwanted off-target effects, we designed an HGFR-specific siRNA containing bases 9 through 11 replaced with their complement (C911), as described previously (46). Briefly, 2 × 104 cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates, and after 16 h a first transfection of siRNAs at a concentration of 50 nM each was performed using the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions. When indicated, a second (repeat) transfection was performed after 24 h using the same protocol. After 48 h, the cells were lysed and depletion of HGFR was detected by Western blot analysis, using α-tubulin for normalization.

Testing of cytotoxicity of candidate compounds.

The cytotoxicity of candidate compounds was assessed using a CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega), which determines the number of viable cells in a culture on the basis of the quantification of ATP. Briefly, 2 × 104 cells were plated per well of a 96-well tissue culture plate and cultured overnight, resulting in monolayers. The cells were treated with 10 μM candidate compounds dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; final concentration, 1% [vol/vol]). After 48 h, the CellTiter-Glo reagent was added and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Compounds that reduced cell viability by >20% were eliminated. For the determination of the concentrations that caused 50% cytotoxicity (CC50s), selected candidate compounds were used at different concentrations (0, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μM) and cell viability was assessed by the CellTiter-Glo test after 24 h.

Screening of kinase inhibitor library.

A549 cells (2 × 104) were plated in each well of an M96 tissue culture plate and cultured overnight, resulting in monolayers. The cells were pretreated with candidate compounds dissolved in DMSO (final concentration, 1% [vol/vol]) for 30 min. rLCMV-LASVGP was added at an MOI of 0.5 in the presence of candidate compounds. After 1 h, the inoculum was removed and the cells were washed briefly and incubated for 16 h in complete medium containing 20 mM ammonium chloride. Infection was quantified by detection of LCMV NP by flow cytometry, as described previously (47).

Fractionation of F and G actin.

Extraction of filamentous (F) and globular (G) actin was performed using an F/G in vitro assay kit (catalog no. BK037; Cytoskeleton Inc.) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 4 × 105 A549 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured for 24 h, resulting in closed monolayers. rLCMV-LASVGP (100 PFU/cell) and VACV (10 PFU/cell) were added at the time points indicated below at 37°C. After a brief wash, the cells were lysed and clarified by low-speed centrifugation (5,000 rpm for 5 min) to remove the cell debris. Cleared supernatants were subjected to ultracentrifugation (53,000 rpm, 1 h; TLA120.2 rotor). The pellets, which contained F actin, and the supernatants, which contained G actin, were suspended in equal volumes of SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The actin contents in the F- and G-actin fractions were assessed by Western blotting using the anti-actin antibody contained in the kit. The signals were quantified by densitometry as described previously (48)

Quantification of dextran-FITC uptake by flow cytometry.

Virus-induced dextran uptake was quantified by flow cytometry as described previously (49, 50). Briefly, A549 cells were serum starved for 16 h and detached with enzyme-free cell dissociation solution (Sigma), and single-cell suspensions (2 × 105 cells/ml) were prepared in PBS containing 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA). Infections were performed at 37°C at the time points indicated below in a volume of 1 ml of PBS, 2% (wt/vol) BSA or PBS, 10% (vol/vol) FCS containing 10-kDa dextran–FITC (500 μg/ml) in the presence of purified rLCMV-LASVGP (MOI = 100) or VACV (MOI = 10). Mock-infected samples, obtained by purification from the supernatants of uninfected cells, were analyzed in parallel. Infection was terminated by addition of 9 ml ice-cold PBS, followed by two washes with cold PBS. To lower the unspecific background, cells were subjected to a brief washing step in 10 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 5.5, followed by neutralization with PBS and fixation with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde. At least 20,000 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was determined using the CellQuant software package and normalized relative to that for the uptake in mock-infected cells in PBS.

Cell surface biotinylation assay.

A549 and Caco-2 cells that had been grown into confluent, polarized monolayers for 9 days on Transwell filter membranes were washed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS), chilled on ice, and subjected to cell surface biotinylation as described previously (42). Briefly, sulfo-NHS-X-biotin [sulfosuccinimidyl-6-(biotinamido)hexanoate; 1 mg/ml in HBSS] was added to the apical and the basolateral chambers, and the reaction was performed in the cold. After 30 min, residual sulfo-NHS-X-biotin was quenched with 50 mM glycine, 0.3% (wt/vol) BSA in HBSS, pH 8.0. After 15 min, cells were washed with HBSS and lysed in 1% (wt/vol) NP-40, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, supplemented with protease inhibitor complex (cOmplete; Roche) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The biotinylated proteins were precipitated with streptavidin as described previously (48) and eluted by boiling in SDS-PAGE buffer. The biotinylated proteins and total cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

Dystroglycan mediates rapid attachment and internalization of LASV into human epithelial cells independently of alternative receptors.

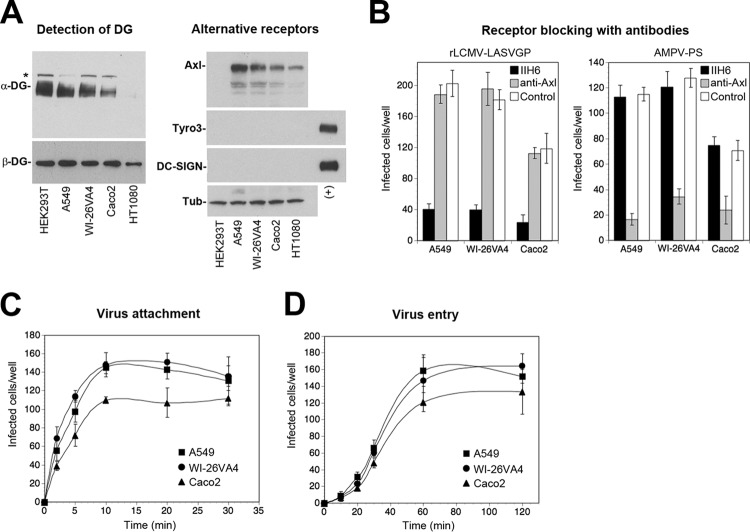

Epithelial tissues lining the human body are crucial targets for LASV during zoonotic transmission and represent likely sites of early viral replication (1). For our studies, we selected cells of the well-characterized human alveolar epithelial line A549, cells of the human airway epithelial line WI-26VA4, and Caco-2 cells, which are a classical model for the human intestinal epithelium. Cells of these cell lines share key characteristics with primary human epithelia and have been used extensively to study viral entry. In a first step, we examined the expression of the candidate receptors DG, Axl, Dtk, DC-SIGN, and LSECtin. Western blot analysis revealed the presence of functionally glycosylated α-DG, detected by MAb IIH6, which recognizes the LARGE-derived sugar polymers implicated in virus and ECM binding (17). An antibody to β-DG revealed the presence of the DG core protein (Fig. 1A). The differences in the apparent molecular masses and band intensities observed for α-DG likely reflect the different chain lengths of the LARGE-derived sugar polymers, as previously reported (20). Detection of alternative LASV receptors in the Western blot revealed the presence of the TAM kinase Axl, whereas Dtk and DC-SIGN were undetectable (Fig. 1A). Staining of cells with antibodies to LSECtin by flow cytometry revealed no signal above the background (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Dystroglycan mediates rapid attachment and internalization of LASV into human epithelial cells independently of alternative receptors. (A) Detection of candidate LASV receptors in epithelial cells. Equal amounts of total cell proteins extracted from the indicated cell lines were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose. Functional DG was detected with MAb IIH6 to glycosylated α-DG, and the presence of the core protein was probed with MAb 8D5 to β-DG. HEK293T cells were included as a positive control, and HT1080 cells lacking functional glycosylation of α-DG (24) were included as a negative control. The band above the signal for glycosylated α-DG (*) may correspond to the unprocessed α/β-DG precursor. The alternative receptors Axl, Tyro3, and DC-SIGN were detected with goat anti-human Axl pAb, anti-human Tyro3 MAb 96201, and anti-DC-SIGN MAb 120507. Human THP-1 monocytes and THP-1-derived immature dendritic cells were used as positive controls (+) for Tyro3 and DC-SIGN, respectively, as described previously (25). Primary antibodies were detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) for development. α-Tubulin (Tub) was detected as a loading control. (B) Blocking of cells with antibodies to DG and Axl. Confluent monolayers of the indicated epithelial cells were blocked with MAb IIH6 to glycosylated α-DG (100 μg/ml), a goat anti-Axl pAb (20 μg/ml), and control antibody for 2 h in the cold. The cells were then infected with rLCMV-LASVGP and AMPV retroviral pseudotypes containing an EGFP reporter (AMPV-PS) at 200 PFU/well for 1 h in the presence of antibodies. Cells were washed with medium supplemented with 20 mM ammonium chloride to prevent secondary infection. After 16 h of incubation in the presence of ammonium chloride, the cells were fixed and infection was detected by IFA using guinea pig serum to LCMV (rLCMV-LASVGP) and rabbit pAb to EGFP (AMPV-PS), combined with Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibodies. Infection was quantified by counting the number of infected cells per well, considering cell doublets to be single infection events. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (C) Virus attachment to epithelial cells. Monolayers of the indicated cell lines were chilled on ice, followed by incubation with rLCMV-LASVGP (200 PFU/well). At the indicated time points, unbound virus was removed by extensive washing in cold medium and the cells were shifted to 37°C. After 1 h at 37°C, 20 mM ammonium chloride was added to the medium and the cells were incubated for a total of 16 h. Virus infection was detected by IFA with MAb 113 to LCMV NP combined with rhodamine red-X anti-mouse IgG, and quantification was performed as described in the legend to panel B. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (D) Endosomal escape of virus. rLCMV-LASVGP (200 PFU/well) was attached to monolayers of the indicated cells in the cold for 2 h. Unbound virus was removed, and the cells were rapidly shifted to 37°C. At the indicated time points, 20 mM ammonium chloride was added and left throughout the experiment. After 16 h, infection was assessed by IFA, as described in the legend to panel C. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). The lower infection rates in Caco-2 cells were consistently observed.

The presence of functionally glycosylated DG in combination with Axl in our cell lines resembled the situation in adult epithelial tissues in vivo (26, 51, 52). We therefore sought to define the relative contribution of the two receptors in LASV entry. Since LASV is a BSL4 pathogen, work with the live virus is restricted to high-containment facilities. To study LASV cell entry in the context of productive arenavirus infection, we therefore used a recombinant LCMV expressing the envelope glycoprotein of LASV (rLCMV-LASVGP). As viral entry is exclusively mediated by the viral envelope, this chimera represents a suitable BSL2 surrogate for LASV entry studies that has been widely used for the characterization of LASV cell tropism in vitro (30, 31, 53, 54) and in vivo (55, 56). For comparison, we included retroviral pseudotypes of the New World arenavirus Amapari virus (AMPV), which enters human cells independently of DG via TAM kinases (57). Virus infection of confluent cell monolayers was performed at a low multiplicity (MOI = 0.01). Perturbation with specific antibodies, MAb IIH6 to the virus-binding sugars on α-DG and a function-blocking polyclonal antibody (pAb) to Axl, revealed that rLCMV-LASVGP entered the epithelial cells tested mainly via DG, whereas Axl seemed dispensable (Fig. 1B). In contrast, infection with AMPV pseudotypes depended on Axl but not DG, in line with the findings of previously published studies (57).

The kinetics of viral attachment and entry into epithelial cells lining the body's surface are likely crucial for the efficiency of zoonotic transmission of the virus. We therefore examined the time course of DG-mediated virus attachment and uptake in the different epithelial cell types. To obtain an estimate of the on rate of virus receptor attachment, rLCMV-LASVGP was added to confluent cells at a low multiplicity (MOI = 0.01) in the cold (4°C), allowing receptor binding without internalization. At different time points, unbound virus was removed and cells were shifted to 37°C to allow entry of attached virus. After 1 h, the cells were treated with the lysosomotropic agent ammonium chloride to prevent further entry via low-pH fusion. When ammonium chloride is added to the cells, it instantly raises the endosomal pH and blocks further low-pH-dependent cellular processes without causing overall cytotoxicity (58, 59). After 16 h, the cells were fixed and productive infection was quantified by detection of LCMV nucleoprotein (NP) by an immunofluorescence assay (IFA). The resulting virus-binding curves revealed half-maximal attachment of the virus after <5 min (Fig. 1C), with only minor differences in the times of half-maximal attachment being detected among the three cell lines. To assess how fast the virus could escape from late endosomes, we then determined the time required to become resistant to ammonium chloride. Briefly, virus was added to cells in the cold to allow receptor binding without internalization. The temperature was shifted to 37°C, and ammonium chloride was added at the time points indicated below and left throughout the experiment. Detection of infected cells after 16 h revealed that rLCMV-LASVGP had similar entry kinetics in all cells, with the half-life for endosomal escape being 30 to 45 min (Fig. 1D), in line with the findings of previously published studies (30, 31) and the entry kinetics of other late-penetrating viruses (60).

Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP shows hallmarks of macropinocytosis.

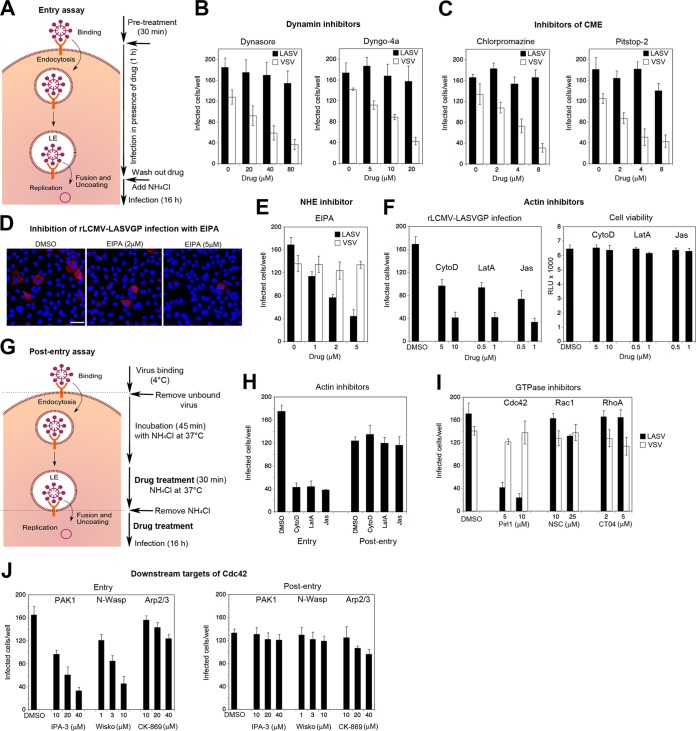

Recent studies in human epithelial cells demonstrated that DG can mediate the endocytosis of its natural ligand, the ECM protein laminin, via a dynamin-dependent pathway (61). Notably, the internalization of laminin was followed by rapid delivery to late endosomes with kinetics similar to those of DG-mediated viral entry observed here. Considering the similarities in DG recognition between LASV and ECM proteins (19, 23), we tested if the virus could hijack the existing DG-associated endocytic pathway used by laminin. Given the similarities in receptor use and in attachment and entry kinetics observed in our different epithelial cell lines (Fig. 1), we initially focused on A549 cells for our further studies. To assess the dynamin dependence of viral entry, we treated A549 cells with the inhibitors dynasore and dyngo-4a. Unwanted off-target effects of these drugs were a significant concern. To preferably target cell entry and to minimize the duration of drug exposure, cells were pretreated for 30 min with inhibitors, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP at a low multiplicity (MOI = 0.01) in the presence of drug, as shown schematically in Fig. 2A. After 1 h, drug was washed out using medium containing ammonium chloride to block further entry. Productive infection was then detected after 16 h by IFA. As a control, we included recombinant LCMV expressing the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus (rLCMV-VSVG), which enters cells independently of DG via CME (62). Both dynamin inhibitors blocked rLCMV-VSVG in a dose-dependent manner, as expected, whereas the entry of rLCMV-LASVGP was hardly affected (Fig. 2B). The insensitivity of rLCMV-LASVGP entry to dynamin inhibitors suggested that the virus may not use the existing DG-associated endocytic routes described for endogenous ECM ligands (61). Since initial studies on LASV entry claimed the involvement of CME (29), we applied two well-established clathrin inhibitors, pitstop-2 (63) and chlorpromazine, which perturb the assembly of clathrin-coated pits at the plasma membrane. Neither of them affected rLCMV-LASVGP infection (Fig. 2C), pinpointing a dynamin- and clathrin-independent pathway.

FIG 2.

Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP into A549 epithelial cells shows hallmarks of macropinocytosis. (A) Schema of the inhibitor experiment. For details, see the text. LE, late endosome. (B, C) Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP is independent of dynamin and clathrin. A549 cells were pretreated with inhibitors of dynamin-2 (dynasore, dyngo-4a) and clathrin (chlorpromazine, pitstop-2) at the indicated concentrations for 30 min, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP (LASV) and rLCMV-VSVG (VSV) (200 PFU/well) in the presence of drugs. After 1 h, the cells were washed 3 times with medium containing 20 mM ammonium chloride, followed by 16 h of incubation in the presence of the lysosomotropic agent. Infection was detected by IFA, as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (D, E) The amiloride drug EIPA blocks entry of rLCMV-LASVGP. A549 cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of EIPA for 30 min, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP (LASV) and rLCMV-VSVG (VSV) (200 PFU/well) in the presence of drugs for 1 h and detection of infection by IFA, as described in the legend to panel B. (D) Example of inhibition of rLCMV-LASVGP infection revealed by IFA using MAb 113 to LCMV NP (red) and counterstaining of nuclei (DAPI, blue). Note the similar intensity of the NP staining with increasing inhibitor concentration. Bar = 20 μm. Cell doublets were counted as one infectious event. (E) Quantification of the images in panel D. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (F) Actin inhibitors block rLCMV-LASVGP infection without causing cell toxicity. A549 cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of cytochalasin D (CytoD), latrunculin A (LatA), and jasplakinolide (Jas) for 30 min, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP (200 PFU/well), as described in the legend to panel B. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). Cytotoxicity was monitored by the CellTiter-Glo assay, as described in Materials and Methods, measuring cellular ATP levels in a luminescence assay. Data are displayed in relative light units (RLU) and are means ± SDs (n = 3). (G, H) Actin inhibitors affect rLCMV-LASVGP entry but not postentry steps of infection. Effects on viral entry were assessed as described in the legend to panel F, with A549 cells being treated with cytochalasin D (10 μM), latrunculin A (1 μM), and jasplakinolide (1 μM). Possible inhibition at postentry steps was assessed as shown schematically in panel G. Cells were pretreated with the drugs for 30 min, followed by incubation in the presence of the drugs and ammonium chloride for 45 min. This allows internalization of the virus and transport to the late endosome without pH-dependent fusion. After 30 min of incubation with drugs in the presence of ammonium chloride, the lysosomotropic agent was removed, allowing restoration of endosomal acidification and low-pH-induced fusion in the presence of drug. After 16 h, cells were fixed and infection was detected as described in the legend to panel B. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (I) Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP depends on Cdc42. A549 cells were pretreated with the DMSO solvent as a control or the inhibitors pirl1 (Cdc42), NSC23766 (NSC; Rac1), and CT04 (RhoA) at the indicated concentrations, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP and rLCMV-VSVG (200 PFU/well) for 1 h in the presence of drugs and detection of infection as described in the legend to panel B. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (J) PAK1 and N-Wasp are involved in rLCMV-LASVGP entry but not postentry steps of infection. Cells were treated with the DMSO vehicle or the inhibitors IPA3 (PAK1), wiskostatin (Wisko; N-Wasp), and CK-869 (Arp2/3) at the indicated concentrations, and the effects on entry or postentry steps were assessed as described in the legend to panel H. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3).

Since recent work with LCMV provided a first link between arenavirus entry and macropinocytosis (34), we applied a panel of diagnostic inhibitors of cellular factors implicated in the regulation of macropinocytosis proposed by Mercer and Helenius (33, 64). A conserved hallmark of macropinocytosis is dependence on NHE, which is sensitive to amiloride drugs like EIPA (33). The productive entry of rLCMV-LASVGP but not rLCMV-VSVG into A549 cells was markedly inhibited by low concentrations of EIPA (Fig. 2D and E). In the presence of the NHE inhibitor, the number of infected cells was reduced, whereas the remaining infected cells exhibited similar levels of NP, consistent with inhibition of viral entry (Fig. 2D). Since dependence on actin is another essential feature of macropinocytosis (12, 64), we treated cells with latrunculin A and cytochalasin D, which disrupt actin filaments, as well as jasplakinolide, which stabilizes actin fibers and blocks actin dynamics. Pretreatment with all three inhibitors reduced subsequent infection with rLCMV-LASVGP, without affecting cell viability (Fig. 2F). Recent studies revealed a crucial role of the actin cytoskeleton in early postfusion events of influenza A virus (IAV) infection that may be conserved among negative-strand RNA viruses (65). To exclude possible effects of actin inhibitors on early postfusion steps of rLCMV-LASVGP infection, we synchronized virus escape from late endosomes with the drug treatment using an assay developed by Banerjee et al. (65), which is shown schematically in Fig. 2G. Briefly, virus was attached in the cold, followed by entry for 45 min in the presence of ammonium chloride, allowing the virus to proceed to late endosomes without undergoing fusion (Fig. 2G). Actin inhibitors were added in the presence of ammonium chloride for another 30 min, followed by the washout of ammonium chloride in the presence of drug. Removal of the lysosomotropic agent restored the endosomal proton gradient within a few minutes, as verified by LysoSensor staining (not shown), allowing the virus to undergo fusion and early replication in the presence of drugs (Fig. 2G). In contrast to the marked reduction of viral entry, none of the actin inhibitors affected postfusion steps of infection (Fig. 2H).

Amiloride inhibitors of NHE block macropinocytosis by lowering the submembranous pH and preventing the activation of the GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 (66). As a next step, we therefore addressed the role of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA in rLCMV-LASVGP entry using the well-characterized inhibitors pirl1, NSC23766, and CT04, respectively. pirl1 specifically reduced productive infection with rLCMV-LASVGP, whereas NSC23766 or CT4 showed only mild effects (Fig. 2I), suggesting a nonredundant role for Cdc42. In line with this, infection of rLCMV-LASVGP was reduced after inhibition of the Cdc42 downstream effectors p21-activating kinase-1 (PAK1) and neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-Wasp) by the inhibitors IPA-3 and wiskostatin, respectively (Fig. 2J). In contrast, targeting of the actin-related protein 2/3 (Arp2/3) complex by the inhibitor CK-869 only slightly affected rLCMV-LASVGP infection. None of the drugs affected early steps postfusion, as assessed by the synchronized release of virus from late endosomes (Fig. 2J). In sum, our data suggested that rLCMV-LASVGP entry via DG involves a macropinocytosis-related pathway different from the DG-mediated endocytosis of laminin (61).

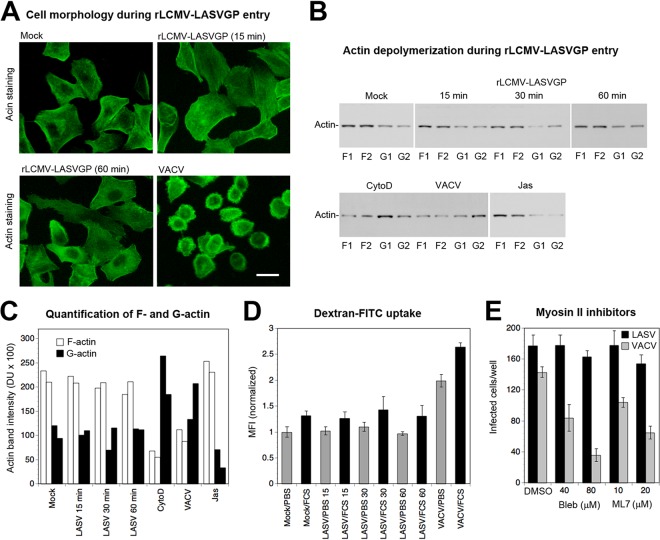

Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP does not affect either overall cellular actin dynamics or bulk fluid uptake.

Macropinocytosis was previously found to be an entry pathway for a range of animal viruses using different cellular receptors (12, 33, 64), including important human pathogens, such as poxviruses (41), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (50), IAV (49), and echovirus 1 (EV-1) (43). While macropinocytosis is constitutively active in some cell types, e.g., professional phagocytes, the pathway needs to be activated in most cells, including epithelia (64). Activation of macropinocytosis by viruses frequently results in dramatic changes in overall cellular membrane and actin dynamics that manifest in overt morphological alterations, accelerated actin depolymerization, and increased bulk fluid uptake (33, 41, 49, 50, 64). As a next step, we therefore investigated to what extent LASV entry affected host cell morphology, actin dynamics, and fluid uptake. To this end, we performed a comparative study with the poxvirus VACV, which activates macropinocytosis for productive entry (41). First, we compared the impact of rLCMV-LASVGP and VACV cell entry on overall cell morphology. Viruses were bound to A549 cells in the cold, unbound virus was removed, and cells were rapidly shifted to 37°C. At the time points indicated below, cells were fixed and alterations in cell shape were visualized by staining for filamentous (F) actin. Consistent with previous reports (41), exposure of A549 cells to VACV (MOI = 3) induced characteristic alterations in cell shape, evidenced by rounding and the appearance of membrane protrusions (Fig. 3A). In contrast, exposure of cells to rLCMV-LASVGP even at a high multiplicity (MOI = 100) did not result in evident changes in cell morphology or the actin distribution over a period of 2 h (Fig. 3A). Since morphological examination of cells may not allow detection of more subtle changes in actin dynamics, we opted for a more quantitative approach. The virus-induced changes in cell morphology and actin distribution that accompany viral entry via macropinocytosis correlate with increased depolymerization of F actin (12, 33, 64). Using a recently developed assay, we quantitatively monitored the ratios of the globular (G) actin monomer to F actin upon exposure of cells to rLCMV-LASVGP, using VACV as a benchmark (50). A549 cells were exposed to rLCMV-LASVGP (MOI = 100) and VACV (MOI = 10). As additional controls, cells were treated with the actin-depolymerizing drug cytochalasin D and jasplakinolide, which stabilizes F actin. At the time points indicated below, cells were lysed under conditions that specifically solubilize G actin but not F actin, as described in Materials and Methods. After fractionation by centrifugation, the supernatants and pellets were analyzed for their actin contents by Western blotting. As expected, engagement of VACV and treatment with cytochalasin D resulted in the marked depolymerization of F actin after 30 min, indicated by an increased ratio of G actin/F actin (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast, G actin/F actin ratios were unaffected after exposure to rLCMV-LASVGP over 60 min (Fig. 3B and C), in line with the lack of overt morphological changes (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP does not affect either overall cellular actin dynamics or bulk fluid uptake. (A) Changes in cell morphology during virus entry. Subconfluent A549 cells were mock treated or exposed to rLCMV-LASVGP (100 PFU/cell) or VACV (3 PFU/cell) for 1 h in the cold. The cells were shifted to 37°C at the indicated time points and fixed, and F actin staining with phalloidin-FITC was performed. Bar = 10 μm. (B) Quantitative assessment of changes in actin polymerization during virus entry. Duplicate specimens of A549 cells were exposed to rLCMV-LASVGP (MOI = 100) and VACV (MOI = 10). Cells incubated with rLCMV-LASVGP were lysed at 15, 30, and 60 min, and cells treated with VACV were lysed at 30 min. Positive and negative controls were treated for 30 min with 10 μM cytochalasin D (CytoD) and 1 μM jasplakinolide (Jas), respectively. Lysis conditions specifically solubilize G actin but not F actin, allowing fractionation by centrifugation. Pellets containing F actin (F1 and F2 from the duplicate specimens) and supernatants containing G actin (G1 and G2 from the duplicate specimens) were mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and equal relative amounts were probed by Western blotting. (C) The actin signals obtained (see panel B) were quantified by densitometry, and values were plotted in arbitrary densitometric units (DU). (D) Changes in colloidal dye uptake during virus entry. Single-cell suspensions of serum-starved A549 cells were mock treated or incubated with rLCMV-LASVGP (100 PFU/cell) and VACV (10 PFU/cell) in the presence of 10-kDa dextran–FITC (1 mg/ml). Infections were performed at 37°C either in PBS, 2% (wt/vol) BSA (PBS) or in PBS containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). At the indicated time points (in minutes), a 9-fold volume of ice-cold PBS was added, followed by a brief acidic wash (pH 5.5) and three washes with cold PBS. Cells were fixed and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Results are represented as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) normalized to that for mock-treated samples in PBS, for which the value was set equal to 1. Data are means ± SDs (n = 4). The mild increase in dextran-FITC uptake in the presence of serum was consistently observed. (E) Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP does not require myosin II. Monolayers of A549 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of blebbistatin (Bleb) and ML7, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP and VACV (200 PFU/well) as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. After 16 h, rLCMV-LASVGP infection was detected by IFA for LCMV NP. Infection with VACV was assessed after 8 h by detection of the EGFP reporter by direct fluorescence microscopy. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3).

Another characteristic feature of virus-induced macropinocytosis is elevated uptake of extracellular fluid, which can be traced by detection of increased internalization of fluorescence-labeled colloids, such as dextran (49, 50). To reduce background fluid uptake, A549 cells were serum starved for 16 h. Purified rLCMV-LASVGP (MOI = 100) and VACV (MOI = 10) were added to cells in suspension in the presence of fluorescence-labeled dextran (dextran-FITC). At the time points indicated below, cells were chilled and subjected to a brief acidic wash step, followed by rapid neutralization. Uptake of dextran-FITC was detected by determination of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of cells by flow cytometry, as described previously (49). As shown in Fig. 3D, exposure of cells to VACV significantly increased the level of dextran-FITC uptake in the presence and absence of serum, as expected. In contrast, exposure to rLCMV-LASVGP did not result in the significantly enhanced uptake of dextran-FITC either in presence or in the absence of serum (Fig. 3D), indicating only minimal changes in bulk fluid uptake.

Productive entry of viruses via macropinocytosis often depends on nonmuscle myosin II, which is involved in the closure of macropinosomes (64). To address a possible role of myosin II in rLCMV-LASVGP entry, A549 cells were pretreated with blebbistatin, an inhibitor of myosin II, and the myosin light chain kinase inhibitor ML7. None of the inhibitors affected rLCMV-LASVGP entry, whereas VACV infection was significantly reduced, as reported previously (41) (Fig. 3E). The lack of detectable changes in cell morphology, actin polymerization, and fluid uptake during the entry of rLCMV-LASVGP suggests that the virus uses a rather unusual pathway of macropinocytosis that apparently causes only minimal perturbation of the host cell.

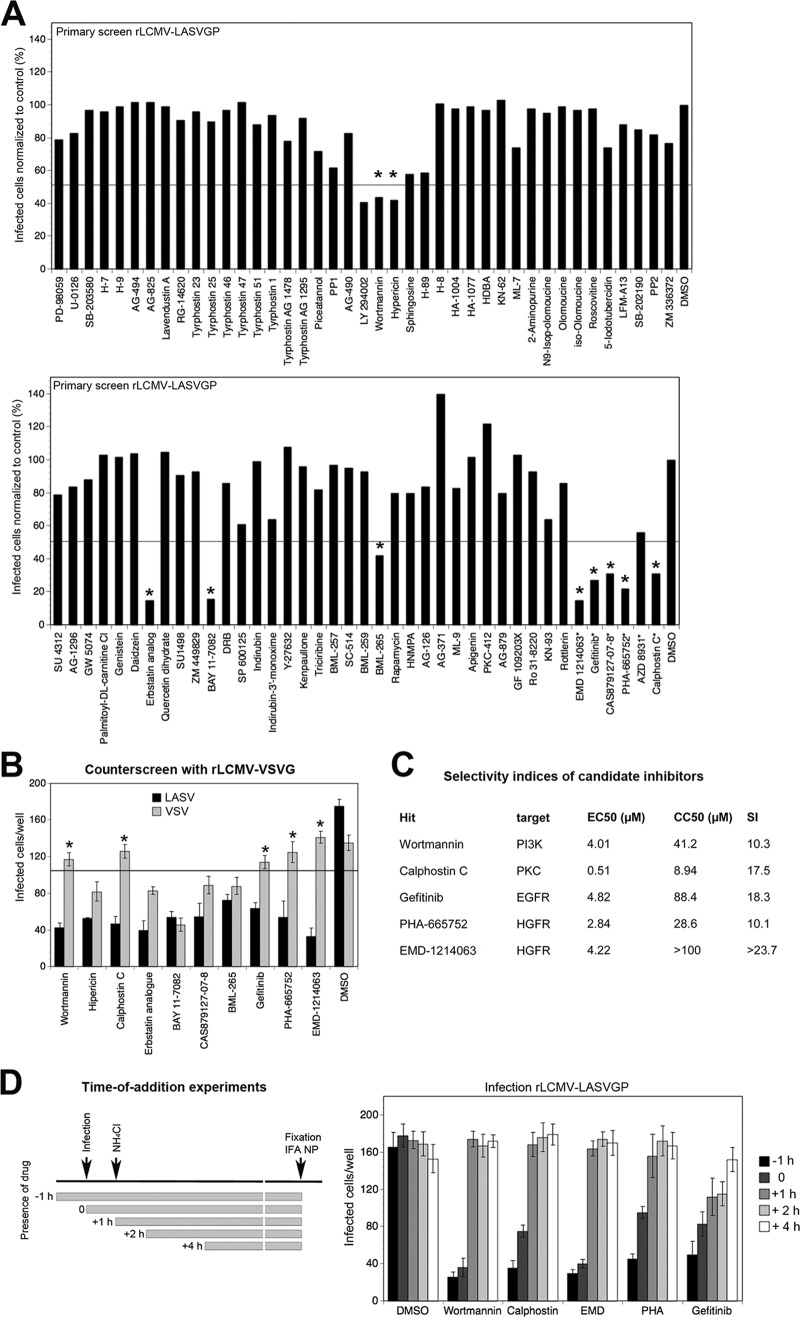

Identification of cellular kinases involved in rLCMV-LASVGP entry.

Macropinocytosis-related pathways are under tight regulation by cellular protein and lipid kinases (64). To identify the cellular kinases involved in the cell entry of rLCMV-LASVGP, we screened a library of over >80 well-defined kinase inhibitors. Specifically, a commercially available kinase inhibitor library from Enzo Life Science was supplemented with inhibitors of kinases implicated in macropinocytosis (see Materials and Methods). To avoid artifacts due to cell toxicity, the kinase inhibitors had undergone an earlier screening by a cell viability test (CellTiter-Glo assay) that detects changes in cellular ATP levels under exact assay conditions. Candidate inhibitors that resulted in >20% reduced cell viability at the concentrations used were excluded from the screen. For positive screening, cells were exposed to the compounds for 30 min, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP (MOI = 0.5) in the presence of drug for 1 h. After washout of the drugs, the cells were cultured in the presence of ammonium chloride for 16 h and productive infection was detected by intracellular staining of LCMV NP and flow cytometry as described previously (47). One example of the results of two independent screens is shown in Fig. 4A. Candidate inhibitors that reproducibly resulted in a >50% reduction of rLCMV-LASVGP infection in both screens were considered hits (Table 1). Using expression of NP as a readout, our initial screen could not distinguish between the effects of the inhibitors on viral entry and effects on inhibition of postentry steps of early replication. To exclude candidate compounds that target postentry steps of infection, the hits were therefore subjected to counterscreening using rLCMV-VSVG. Among the initial hits, the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor calphostin C, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor wortmannin, the epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor gefitinib, and the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR) inhibitors PHA-665752 and EMD 1214063 showed the ability to reduce infection with rLCMV-LASVGP but not infection with rLCMV-VSVG (Fig. 4B). The other EGFR inhibitors tested significantly affected infection with rLCMV-VSVG, suggesting effects on postentry steps or VSVG-mediated cell entry. For each selected hit, dose-response curves were established, and the effective dose at 50% inhibition (i.e., the 50% effective concentration [EC50]) was determined (Fig. 4C). To quantify toxicity, drugs were applied under the assay conditions and the concentration that caused a 50% reduction in cell viability (i.e., the CC50) in the CellTiter-Glo assay (Fig. 4C). For each hit, the selectivity index (SI), which is equal to CC50/EC50, was calculated. Observed SIs of >10 indicated that the inhibitors were specific. To further pinpoint cell entry as the target of our candidate inhibitors, we performed time-of-addition experiments. All inhibitors tested were highly active when added before or at the time of infection (Fig. 4D). Calphostin C, wortmannin, PHA-665752, and EMD 1214063 showed only mild postentry effects. In contrast, gefitinib showed some degree of inhibition when added at later time points. This had been observed to a greater extent with the other EGFR inhibitors (Fig. 4B), suggesting a significant off-target effect on viral replication and gene expression.

FIG 4.

Identification of cellular kinases involved in rLCMV-LASVGP entry. (A) Screening of a library of kinase inhibitors against rLCMV-LASVGP entry. Monolayers of A549 cells were pretreated with inhibitors for 30 min. Infection with rLCMV-LASVGP (MOI = 0.5) was performed in the presence of drugs for 1 h, followed by washout and addition of ammonium chloride to prevent secondary infection. After 16 h, infection was quantified by flow cytometry via intracellular staining of LCMV NP. The data were normalized to those for the DMSO vehicle control, which was set to a value of 100%. Candidate compounds marked with an asterisk were not part of the original library and were screened in parallel under the same conditions. Hits that reduced infection in two independent screens by >50% are indicated (*). (B) Counterscreening of selected candidate compounds. A549 cells were pretreated with the indicated candidate compounds as described in the legend to panel A, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP and rLCMV-VSVG (200 PFU/well) as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. All candidates were used at 10 μM, with the exception of calphostin C, which was used at 1 μM. Infection was assessed by IFA. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). Compounds were considered specific inhibitors of rLCMV-LASVGP if they reduced infection of the control virus rLCMV-VSVG by <20% (*). (C) Selected candidate compounds, their putative targets, and their EC50, CC50, and SI values determined in A549 cells. Note the relatively high toxicity of calphostin C (CC50 < 10 μM) in our system. (D) Time-of-addition experiments. A549 cells were infected with rLCMV-LASVGP (200 PFU/well), and candidate inhibitors were added at the different time points pre- or postinfection at the concentrations used for the assay whose results are presented in panel B. Virus was added at time point 0, followed by washing and addition of ammonium chloride after 1 h (+1 h). Ammonium chloride was kept throughout the experiment, and cells were subjected to IFA after 16 h. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3).

TABLE 1.

Hits obtained from targeted kinase inhibitor screena

| Candidate compound | Target |

|---|---|

| Wortmannin | PI3K |

| Hypericin | PKC |

| Calphostin C | PKC |

| Erbstatin analogue | EGFR |

| BAY 11-7082 | IKK |

| CAS879127-07-8 | EGFR |

| BML-265 | EGFR |

| Gefitinib | EGFR |

| PHA-665752 | HGFR |

| EMD 1214063 | HGFR |

Candidate compounds that reproducibly reduced infection of rLCMV-LASVGP by >50% in two independent screens and their known targets are listed. IKK, IκB kinase.

Conserved profile of cellular factors involved in rLCMV-LASVGP cell entry.

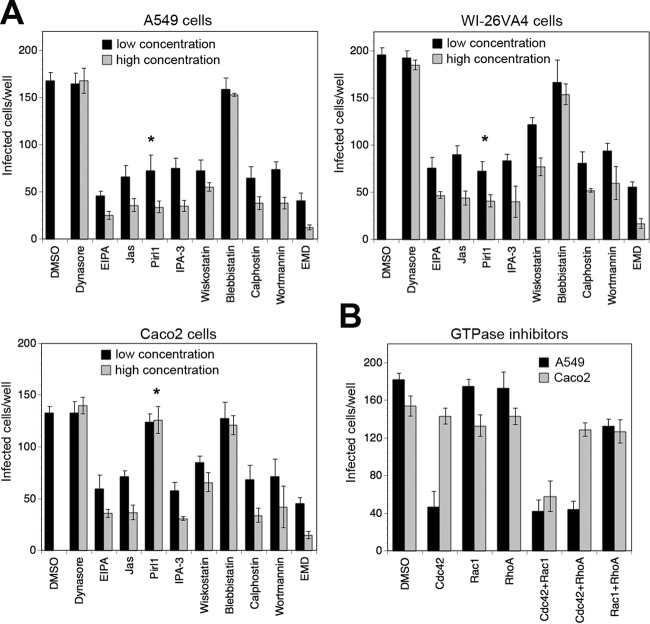

The profile of cellular factors involved in viral entry via macropinocytosis frequently varies between cell types (33, 64). To exclude the possibility that the pattern obtained in A549 cells in our studies performed so far represented a unique feature of this cell line, we validated the profile in other human epithelial cell lines, WI-26VA4 and Caco-2. For this purpose, we defined a panel of selected inhibitors targeting the key cellular factors implicated in our pathway listed in Table 2. To control for overt off-target effects, cell viability was verified in parallel cultures using the CellTiter-Glo assay as described above. Screening of rLCMV-LASVGP entry into the different cells with our panel of selected drugs revealed similar inhibitory profiles (Fig. 5A). A notable exception was the Cdc42 inhibitor pirl1, which blocked rLCMV-LASVGP entry into A549 and WI-26VA4 cells but not Caco-2 cells (Fig. 5A). To follow up on this issue, A549 and Caco-2 cells were treated with inhibitors of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA either alone or in combination. Only the combination of inhibitors of Cdc42 and Rac1 markedly reduced infection in Caco-2 cells, suggesting redundant roles of the two GTPases, at least in some cell types (Fig. 5B).

TABLE 2.

Panel of selected inhibitorsa

| Inhibitor | Target | Low, high concn (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Dynasore | Dynamin | 40, 80 |

| EIPA | NHE | 2, 5 |

| Jasplakinolide | Actin | 0.5, 1 |

| Pirl1 | Cdc42 | 5, 10 |

| IPA-3 | PAK1 | 10, 40 |

| Blebbistatin | Myosin kinase II | 40, 80 |

| Wiskostatin | N-Wasp | 3, 10 |

| Calphostin C | PKC | 1, 2 |

| Wortmannin | PI3K | 10, 20 |

| EMD 1214063 | HGFR | 5, 10 |

The selected inhibitors, their targets, as well as the concentrations used are indicated.

FIG 5.

Conserved profile of cellular factors involved in rLCMV-LASVGP entry. (A) Inhibition of rLCMV-LASVGP infection with selected inhibitors in different epithelial cell lines. Monolayers of A549, WI-26VA4, and Caco-2 cells were treated with the indicated inhibitors at the concentrations listed in Table 2. After 30 min, rLCMV-LASVGP (200 PFU/well) was added in the presence of drugs. After 1 h, the drugs were washed out with medium containing 20 mM ammonium chloride and infection was assessed by IFA after 16 h. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). The inconsistent results obtained with pirl1 are indicated (*). (B) Combination with GTPase inhibitors. A549 and Caco-2 cells were treated with the indicated combinations of GTPase inhibitors at higher concentrations (Table 2), and infection was performed as described in the legend to panel A. Data given are means ± SDs (n = 3).

When grown as monolayers in tissue culture plates, the human epithelial cell lines used in our study adopted some characteristics of polarization. However, it was not feasible to quantitatively assess the integrity of tight junctions under these conditions, which is a limitation of this culture system. We therefore sought to validate our findings in polarized A549 and Caco-2 cell cultures in Transwell chambers. Briefly, A549 and Caco-2 cells were seeded on Transwell filters. A549 cells were allowed to settle for 2 days, followed by culture at the air-liquid interface supplemented with medium from the basal chamber, as described previously (42). After 9 days in culture, the junctional integrity of the monolayers was validated using fluorescent colloidal dye transport. This assay assesses the permeability of cell layers via paracellular passage (67) and reveals unspecific leakage between the two chambers (for details, see Materials and Methods). Caco-2 cell cultures were kept with medium in both the apical and the basolateral chambers as described previously (43), and the integrity of the monolayers was validated after 4 to 5 days.

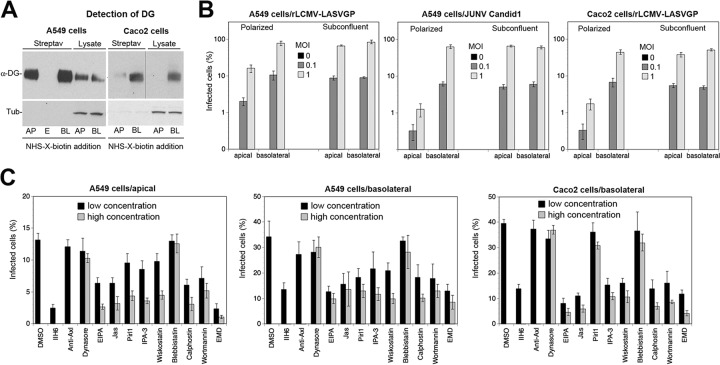

First, we sought to detect the presence of glycosylated α-DG at the apical and the basolateral surfaces by domain-specific biotinylation of surface proteins (68). Site-specific biotinylation performed in our polarized A549 cells revealed the presence of functional DG at both the apical and the basolateral surfaces (Fig. 6A). This was consistent with the findings of earlier studies on DG expression on primary human respiratory epithelial cell cultures (69). In contrast, in Caco-2 cells, DG was found predominantly at the basolateral face (Fig. 6A), as previously reported (70).

FIG 6.

Conserved profile of cellular factors involved in rLCMV-LASVGP entry into polarized cells. (A) Detection of functional DG at the apical and basolateral surfaces of polarized A549 and Caco-2 cells. Cells were cultured on Transwell filters to obtain polarized monolayers, as described in Materials and Methods. Cell surface proteins were biotinylated by adding a membrane-impermeant sulfo derivative of NHS-X-biotin to the apical (AP) and basolateral (BL) chambers, respectively. After quenching of the reaction, cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were separated by streptavidin (Streptav) agarose. Biotinylated proteins and total cell lysates were probed with MAb IIH6 to α-DG in the Western blot. The amount of cell lysate corresponds to 1/5 of the biotinylated fraction for A549 cells and 1/2 of the biotinylated fraction for Caco-2 cells. To check for the specificity of cell surface biotinylation, samples were probed for the presence of the intracellular protein α-tubulin (Tub). Note the absence of detectable α-tubulin in the fraction of biotinylated proteins. Slot E indicates an empty lane between the apical and basolateral samples. The apparent shift to a higher relative molecular mass of α-DG in the apical fraction was not consistently observed and may be due to a gel artifact. Samples in the α-DG blot of Caco-2 cells were run on the same membrane, with a vertical line indicating the movement of lanes for clarity. (B) Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP and JUNV into polarized A549 and Caco-2 cells. Polarized monolayers of A549 and Caco-2 cells cultured as described in the legend to panel A were infected with rLCMV-LASVGP and JUNV Candid 1 via the apical (top) and the basolateral (bottom) compartments at the indicated multiplicity. After 1 h, 20 mM ammonium chloride was added and infection was carried out for 16 h. Cells were dissociated, and infection was determined by intracellular staining for LCMV NP (MAb 113) and JUNV antigen (mouse polyclonal serum to New World arenaviruses) in an IFA. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (C) Inhibition of rLCMV-LASVGP infection of polarized A549 and Caco-2 cells with selected inhibitors. Polarized monolayers were pretreated with the indicated selected set of inhibitors (Table 2), followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP via the apical chamber (MOI = 1) and the basolateral chamber (MOI = 0.5) for A549 cells. Caco-2 cell monolayers were infected only via the basolateral chamber (MOI = 1) due to the low level of infection via the apical site seen in panel B. Antibody IIH6 to DG and pAb to Axl were used at 100 and 20 μg/ml, respectively. After 1 h, the drugs were washed out with medium containing 20 mM ammonium chloride and infection was assessed by IFA after 16 h. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3).

To determine the efficacy of LASV cell entry into polarized A549 cell monolayers via the apical and the basolateral sites, rLCMV-LASVGP was added to the two chambers. After 1 h at 37°C, cells were washed extensively, and new medium containing ammonium chloride was added to avoid secondary infection via lateral spread of progeny virus. After one round of replication (16 h), the monolayers were dissociated and infected cells quantified by detection of LCMV NP. For comparison, we used the New World arenavirus Junin virus vaccine strain Candid 1, which uses human transferrin receptor 1 as a cellular receptor (71) and enters polarized airway epithelial cell monolayers mainly via the basolateral site (69).The rLCMV-LASVGP chimera was able to infect polarized A549 cells via both the apical and the basolateral faces but with consistently higher infection rates (3- to 5-fold) via the basolateral site (Fig. 6B). As expected, JUNV had a strong preference for entry via the basolateral face, in line with previous reports (69). The known basolateral location of transferrin receptor 1 in airway epithelial cells readily explained the asymmetry in JUNV entry in A549 cells. However, the preferred entry of rLCMV-LASVGP via the basolateral face seemed inconsistent with the similar concentrations of functional DG on both faces of the A549 cell monolayer (Fig. 6A). Entry of rLCMV-LASVGP into polarized Caco-2 cells occurred predominantly via the basolateral face (Fig. 6B), as expected, on the basis of the polarized expression of DG (Fig. 6A).

To examine rLCMV-LASVGP entry into polarized A549 and Caco-2 cell monolayers, cells were pretreated with our panel of selected inhibitors supplemented by MAb IIH6 to DG and anti-Axl pAb. These studies revealed an overall similar inhibitory pattern for rLCMV-LASVGP entry into polarized A549 and Caco-2 cell monolayers compared to that into monolayers of cells grown in normal tissue culture plates (Fig. 6C). This suggests that the DG-linked macropinocytosis-related pathway is also operational during viral entry into polarized cells with similar profiles of cellular factors.

Validation of HGFR as a candidate drug target to block LASV entry.

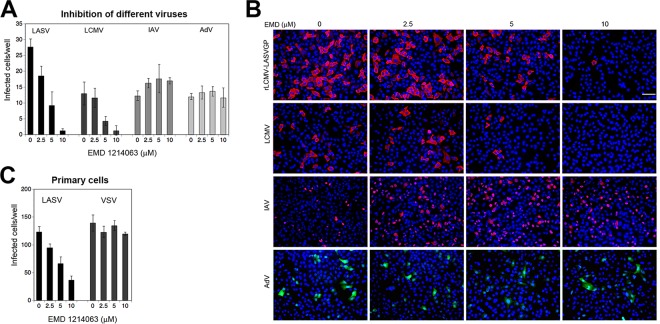

Our small kinase inhibitor screen identified HGFR to be a novel putative entry factor for rLCMV-LASVGP. While RTKs like EGFR have been linked to the entry of many viruses via macropinocytosis (64), the marked reduction of rLCMV-LASVGP entry caused by two inhibitors of HGFR was rather unexpected and raised the question about the physiological significance. In humans, HGFR is expressed on epithelial cells, endothelial cells, hepatocytes, and hematopoietic cells, which are important targets of LASV in vivo (72). The aberrant activation of HGFR is observed in many cancer types, and HGFR has been identified to be a promising drug target for anticancer therapy (73). To evaluate HGFR as a possible target to block LASV entry, we employed the compound EMD 1214063, which is a member of a new class of highly specific HGFR inhibitors currently in clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumors (74). Against rLCMV-LASVGP entry, EMD 1214063 showed an EC50 of 4.2 μM and high selectivity (SI > 20), allowing its use as a candidate drug for proof-of-concept studies. In a first step, we assessed the specificity of EMD 1214063, comparing its effects on rLCMV-LASVGP, LCMV, IAV, and human adenovirus (AdV) serotype 5. EMD 1214063 efficiently blocked the entry of rLCMV-LASVGP and LCMV but not that of IAV and Ad5 (Fig. 7A and B).

FIG 7.

Antiviral activity of the kinase inhibitor EMD 1214063 (EMD). (A) Inhibition of different viruses with EMD 1214063. Monolayers of A549 cells were pretreated with the indicated concentration of EMD 1214063 for 30 min, followed by infection with the different viruses (MOI = 0.3) in the presence of drug. After 1 h, the cells were washed with medium containing 20 mM ammonium chloride. Infection of rLCMV-LASVGP and LCMV was detected after 16 h by IFA as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. IAV infection was assessed after 6 h by staining for IAV N protein, whereas AdV was detected via its EGFP reporter by direct fluorescence after 24 h. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (B) Representative images of inhibition experiments. LCMV and IAV antigens are in red, EGFP is in green, and nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Bar = 100 μM. (C) Antiviral effect of EMD 1214063 in primary human respiratory epithelial cells. Monolayers of primary human bronchiolar epithelial cells isolated from human bronchi were cultured in M96 plates for 3 days to obtain closed cell monolayers. The cells were pretreated with the indicated concentration of EMD 1214063 for 30 min, followed by infection with rLCMV-LASVGP (LASV) and rLCMV-VSVG (VSV) at 1,000 PFU/well for 1 h. The cells were washed, and infection was detected by IFA after 16 h, as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3).

Next, we sought to validate the inhibitory activity of EMD 1214063 on rLCMV-LASVGP entry in primary human respiratory epithelial cells. To this end, we used human bronchial epithelial cells isolated ex vivo from human bronchi (for details, see Materials and Methods). Infection of primary human bronchial epithelial cells with rLCMV-LASVGP was blocked by EMD 1214063 in a dose-dependent manner, but infection of the cells with rLCMV-VSVG was not (Fig. 7C).

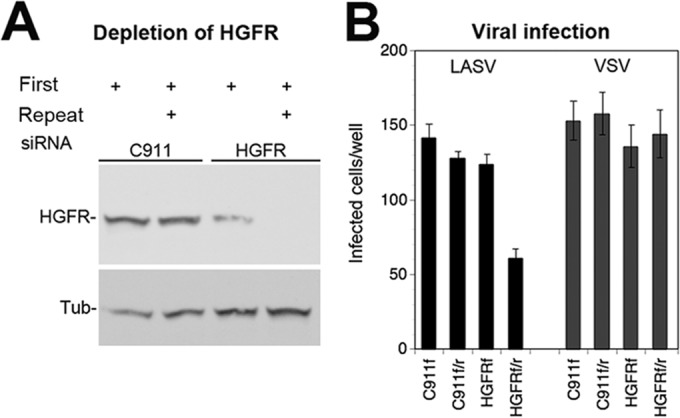

To address a possible role of HGFR in the entry of rLCMV-LASVGP in a complementary manner, we performed RNAi using an HGFR-specific siRNA and the corresponding off-target control, as described in Materials and Methods. Depletion of HGFR by two sequential transfections of specific siRNA resulted in a marked reduction of HGFR protein expression after 72 h (Fig. 8A). Depletion of HGFR resulted in significantly reduced infection with rLCMV-LASVGP but not with rLCMV-VSVG (Fig. 8B), further suggesting a role of HGFR in rLCMV-LASVGP entry.

FIG 8.

Infection of rLCMV-LASVGP in A549 cells depleted of HGFR. (A) Depletion of HGFR by RNAi. A549 cells were transfected with siRNAs specific for HGFR and the corresponding control siRNA (C911). An initial transfection (First) was performed 16 h after plating. Where indicated, a second (Repeat) transfection was performed after another 24 h. Expression of HGFR was determined 72 h after the first transfection by Western blotting. α-Tubulin (Tub) was detected as a loading control. Note the only partial depletion of HGFR observed after a single transfection with siRNA. (B) Viral infection of HGFR-depleted cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs as described in the legend to panel A, with the first transfection only (f) and the combined first and repeat transfections (f/r) being indicated. At 72 h posttransfection, cells were infected with rLCMV-LASVGP (LASV) and rLCMV-VSVG (VSV) (200 PFU/well). Infection was detected after 16 h by IFA for LCMV NP as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3).

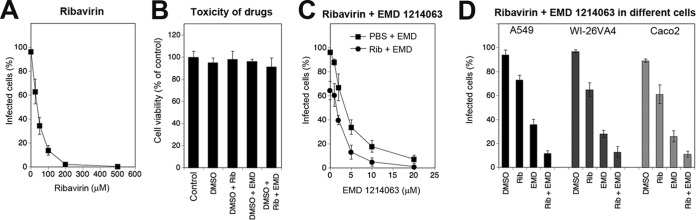

In vitro and in vivo studies have documented the prophylactic and therapeutic value of ribavirin (Rib) against several arenaviruses, including LASV (6, 75). We therefore investigated the combinatorial effects of EMD 1214063 and Rib on rLCMV-LASVGP multiplication. The high degree of conservation of the replication machinery of LCMV and LASV results in similar effects of Rib on both viruses (75), allowing the use of our chimera for the first combinatorial drug studies to be performed with these drugs. First, we established a dose-response curve for the activity of Rib against rLCMV-LASVGP in A549 cells (Fig. 9A) and identified a low Rib concentration that showed partial efficacy (25 μM). Next, we assessed the cytotoxicity of Rib (25 μM) and EMD 1214063 (20 μM) individually as well as in combination in A549 cells. A549 cells tolerated both drugs without a significant drop in viability (Fig. 9B). To study the antiviral effects of combinations of Rib and EMD 1214063, A549 cells were infected with rLCMV-LASVGP at a low multiplicity (MOI = 0.01), followed by treatment with increasing concentrations of EMD 1214063 (0 to 20 μM) either alone or in combination with 25 μM Rib, which by itself resulted in only partial inhibition of viral infection (Fig. 9A). After 48 h, viral infection was assessed by flow cytometry. The combination of EMD 1214063 with Rib resulted in a stronger antiviral effect (Fig. 9C) that was conserved in A549, WI-26VA4, and Caco-2 cells (Fig. 9D). Together, our data showed the antiviral activity of EMD 1214063 against rLCMV-LASVGP and the additive drug effects of EMD 1214063 in combination with Rib.

FIG 9.

Additive antiviral activity of EMD 1214063 and ribavirin. (A) Inhibition of rLCMV-LASVGP infection with Rib. A549 cells were infected with rLCMV-LASVGP at an MOI of 0.01. After removal of unbound virus, fresh medium containing the indicated concentrations of Rib was added. After 48 h, cells were detached, single-cell suspensions were prepared, and viral NP was detected by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (B) Cytotoxicity of the combination of Rib and EMD 1214063 in A549 cells. Monolayers of A549 cells were treated with Rib (25 μM), EMD 1214063 (10 μM), and combinations thereof. After 48 h, cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay as described in the legend to Fig. 2F. Values were normalized to those for cells treated with the DMSO vehicle. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (C) Combined treatment of infected cells with Rib and EMD 1214063. A549 cells were infected with rLCMV-LASVGP at an MOI of 0.01. After removal of unbound virus, fresh medium containing the indicated concentration of EMD 1214063 either alone (PBS) or in combination with 25 μM Rib (Rib) was added. After 48 h, infection was assessed as described in the legend to panel C. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3). (D) Combined treatment with Rib and EMD 1214063 in different cells as described in the legend to panel E. Data are means ± SDs (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Over the past few years, several novel candidate LASV receptors have been identified, suggesting complex receptor use (24, 25, 57). Recent work provided further insights into the endosomal transport of the virus (31) and uncovered a receptor switch at the level of the late endosome (35) that shows interesting parallels to that in filoviruses (36). However, the mechanism of endocytosis by which LASV overcomes the barrier of the plasma membrane remained largely unknown. Here we sought to close this gap and examined the pathway underlying LASV entry using a well-established BSL2 surrogate system and relevant human cell models. We provide evidence that LASV entry is via its high-affinity receptor DG and occurs via an unusual pathway of macropinocytosis, and we identified cellular factors involved.

The highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed ECM receptor DG was the first cellular receptor identified for LASV and other arenaviruses (15). Subsequent studies revealed that LASV-receptor binding closely mimics the molecular recognition of DG by endogenous ligands and critically depends on posttranslational modification by LARGE (18, 19, 76). Recent expression cloning identified the TAM receptors Axl and Tyro3, as well as the C-type lectins DC-SIGN and LSECtin, to be candidate LASV receptors (24). On the basis of their known expression patterns, DC-SIGN and LSECtins may contribute to LASV entry into some cell types (77), but their exact role is currently unclear (25). The TAM kinases Tyro3 and Axl are broadly expressed and highly conserved receptors for the phosphatidylserine (PS)-binding serum proteins Gas6 and protein S, which are involved in removal of apoptotic cells (26, 52). TAM kinases have recently been implicated in viral entry by apoptotic mimicry, which is characterized by recognition of PS displayed on the viral lipid envelope by cellular PS receptors (78). Viral apoptotic mimicry is currently recognized to be an entry pathway for a broad spectrum of enveloped viruses, including arenaviruses (78). Accordingly, ectopic expression of Axl and Tyro3 increased LASV infection in otherwise refractory cells (24). However, Axl seemed to be dispensable for LASV entry into cells expressing functional DG (24). Our studies using antibody perturbation in a panel of human epithelial cells coexpressing DG and Axl confirmed this, supporting a role of Axl in DG-independent LASV entry. Considering the role of epithelial cells as an early target during virus transmission, we examined the kinetics of virion attachment and entry. We found rapid viral attachment to cellular DG within <5 min. The data suggest that the DG displayed at the cell surface may rapidly capture free virus via its LARGE-derived sugar chains, in analogy to glycosaminoglycans in other viral systems (14), rendering engagement of PS receptors obsolete. Whether DG acts primarily as an attachment factor cooperating with an unknown coreceptor(s) or whether it can function as an authentic entry receptor remains unclear at present.

Recent studies provided a first link between arenavirus entry and macropinocytosis (34). We therefore performed a systematic analysis of rLCMV-LASVGP entry using a panel of diagnostic inhibitors targeting known cellular factors implicated in macropinocytosis (33, 64). We found that DG-mediated LASV entry into a panel of well-established epithelial cells, including polarized cell monolayers, was independent of dynamin and clathrin. The entry of rLCMV-LASVGP was highly sensitive to the NHE inhibitor EIPA and critically depended on the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton, hallmarks of macropinocytosis. Examination of candidate cellular factors involved in macropinocytosis revealed that Cdc42 and its downstream effectors, PAK1 and N-Wasp, were required for LASV entry, whereas Rac1, RhoA, the Arp2/3 complex, myosin II, and myosin light chain kinase seemed to be dispensable. Interestingly, a recent screen of small molecules for inhibitors of productive LASV infection identified the PAK1 inhibitor OSU-03012 to be a major hit (79), in line with our findings. Validation of the key regulatory factors in other human epithelial cells and polarized epithelial cell monolayers suggested some conservation of the entry pathway. An apparent exception was Cdc42, which was crucial in A549 and WI-26VA4 cells but seemed redundant in Caco-2 cells. The cell type-specific roles of GTPases are in line with the Cdc42-independent entry of LCMV into rodent fibroblasts reported by Iwasaki et al. (34).

Macropinocytosis has emerged to be a major pathway of cell entry currently found to be used by >20 RNA and DNA viruses (64). However, this pathway has so far not been linked to DG, which mediates the endocytosis of laminin in a dynamin-dependent manner (61). Our data suggest that, despite striking similarities in DG recognition between LASV and laminin (23), the virus does not mimic the dynamin-dependent uptake of ECM proteins. Our studies on LASV entry further revealed dependence on a specific set of cellular regulators of classical macropinocytosis, whereas other factors seemed to be dispensable. Indeed, examination of the cellular factors involved in viral cell entry via macropinocytosis revealed variations among different viruses (33, 64). This suggests that the pathogens can recruit specific sets of regulatory factors according to their needs. In all cell lines tested in our study, LASV entry strictly depended on actin, which is considered a hallmark of macropinocytosis (33). However, in monkey kidney CV-1 cells, we previously observed the actin-independent entry of rLCMV-LASVGP (30), which seems to contradict our current findings in human cells. A similar discrepancy was found for EV-1, which enters human Caco-2 epithelial cells via an actin-dependent macropinocytosis-related pathway (43) but can infect CV-1 cells independently of actin (80), suggesting perhaps an aberrant phenotype of this primate cell line.