Abstract

Renal biopsy was performed for the first time more than one century ago, but its clinical use was routinely introduced in the 1950s. It is still an essential tool for diagnosis and choice of treatment of several primary or secondary kidney diseases. Moreover, it may help to know the expected time of end stage renal disease. The indications are represented by nephritic and/or nephrotic syndrome and rapidly progressive acute renal failure of unknown origin. Nowadays, it is performed mainly by nephrologists and radiologists using a 14-18 gauges needle with automated spring-loaded biopsy device, under real-time ultrasound guidance. Bleeding is the major primary complication that in rare cases may lead to retroperitoneal haemorrhage and need for surgical intervention and/or death. For this reason, careful evaluation of risks and benefits must be taken into account, and all procedures to minimize the risk of complications must be observed. After biopsy, an observation time of 12-24 h is necessary, whilst a prolonged observation may be needed rarely. In some cases it could be safer to use different techniques to reduce the risk of complications, such as laparoscopic or transjugular renal biopsy in patients with coagulopathy or alternative approaches in obese patients. Despite progress in medicine over the years with the introduction of more advanced molecular biology techniques, renal biopsy is still an irreplaceable tool for nephrologists.

Keywords: Renal biopsy, Acute kidney injury, Bleeding, Haematuria, Hematoma, Chronic renal failure

Core tip: Percutaneous renal biopsy is an irreplaceable tool in the clinical practice of nephrologists to determine diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of several kidney diseases. This procedure is considered safe if it is performed in well-trained centers. Main indications are acute glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome. Since bleeding is the major primary complication, careful evaluation of risks and benefits must be considered. The risk of complications in patients with coagulopathy may be reduced by using laparoscopic or transjugular renal biopsy or alternative approaches in obese patients. Despite progress in medicine over the years, renal biopsy is still an irreplaceable tool for nephrologists.

INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous renal biopsy (PRB) is still considered an irreplaceable tool for diagnosis, prognosis and choice of treatment of several primary or secondary kidney diseases. The indications uniformly recognized by most nephrologists are represented by nephritic and/or nephrotic syndrome and unexplained acute or rapidly progressive renal failure[1]. Primary glomerulonephritis are the more common renal disease in renal biopsy registries. Among them IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most frequent renal diagnosis. Regarding systemic diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the most frequent indication for PRB, because this last determines the level of activity and/or chronicity of the lesions and the reversibility of renal lesion as a result of therapy. PRB can also be helpful in vasculitis to assess the severity of the damage and the potential reversibility after therapy. In diabetes the use of PRB is motivated by a relatively recent or very late appearance of proteinuria > 1 g and/or a rapid decline in GFR and/or active urinary sediment, in the absence of other signs of microangiopathy (retinopathy and neuropathy); in fact, in these patients primitive forms of glomerular diseases are frequently reported, superimposed or not to the typical lesions of diabetes. In advanced chronic renal failure, PRB is useful to assess a rescue therapy or to know the causal nephropathy in view of renal transplantation[2].

PRB is also an informative procedure in renal transplantation, both in the postoperative, for the differential diagnosis of acute rejection vs other diseases, and in follow-up of organ transplantation for differential diagnosis between recurrence of primary renal disease, development of glomerulonephritis ex novo, and acute or chronic rejection (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of Indications for renal biopsy

| Nephrotic syndrome |

| Acute kidney injury (when rule out obstruction, and pre-renal causes) |

| Systemic disease with renal dysfunction (in diabetic patients only if it presents with atypical features) |

| Non-nephrotic proteinuria, and in some circumstances isolated microscopic hematuria |

| Unexplained chronic kidney disease |

| Familial renal disease (may avoid biopsy in other family members affected) |

| Renal transplant dysfunction |

HISTORY

The first renal biopsy of native kidney was performed in 1901 in a surgical procedure for renal decapsulation in the treatment of a Bright’s syndrome[3]. The PRB was born in 1944 when Nils Alwall adapted a technique for percutaneous liver biopsy in the kidney, using an aspiration needle technique[4] with a radiographic procedure for the localization of the right kidney and keeping the patient in a sitting position. With this innovative method, he obtained adequate tissue in ten of the thirteen patients[5]. However, this procedure has been for the first time described in the literature by Iversen and Brun[6] in 1951, which also used an aspiration needle and the sitting position but, in contrast to Nils Alwall, they used intravenous pyelography for localization of the right kidney; unfortunately they obtained adequate tissue only in 53% of patients[6]. Given the poor results of this technique, Kark et al[7] in 1954 made significant changes including the prone position of the patients with a sandbag placed under the abdomen to reduce the mobility of the kidney and the introduction of a new type of needle, the Franklin-modified Vim-Silverman needle, which trapped the tissue in the needle and then sheared it off, achieving adequate tissue in 96% of patients and no major complications. To localize the lower pole of the kidney they used as landmark the distances between the vertebral spinous processes and the 11th and 12th ribs, and the movement of a finder needle following a deep inspiration[7]. Over the years the technique has been improved more and more, increasing the adequacy of the sample and reducing the risk of complications.

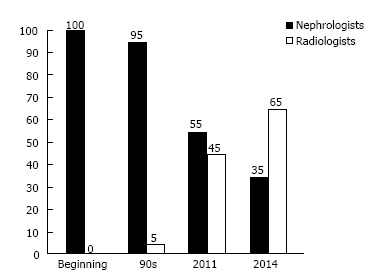

In 1962 the use of radiological images was introduced for the localization of the kidney, later replaced by the ultrasound real-time imaging. Since then this procedure, which was initially performed by nephrologists, has gradually become a prerogative of radiologists. In fact, between 1964 and 1974 the PRB was performed in 95% of cases by nephrologists[8], while in 1980s the number of nephrologists who performed the PRB was gradually reduced in favour of radiologists and in 2011, Lane et al[9] showed that radiologists were the main performers of this technique (Figure 1)[10].

Figure 1.

Rate of performers (nephrologists and radiologists) of renal biopsy along the course of the years[10].

A recent european survey stated that in 60% of the centers renal biopsy is performed by nephrologysts, in 30% by radiologists and in 5% by nephrologysts and radiologists[11]. Today, the standard procedure for PRB involves the use of real-time ultrasound and automated spring-loaded biopsy device[12].

NEEDLE TYPES AND SIZE

There are different types of biopsy needles and the first used was an aspiration needle, subsequently replaced by the cutting Vim-Silverman needle, which trapped the tissue in the needle and then sheared it off. The evolution of the latter is the Tru-Cut needle, which is a manually operated sheathed needle designed for manual capture of high-quality tissue samples with minimal trauma to the patient. Today it is replaced by automatic spring-loaded biopsy guns and semi-automatic biopsy guns with better and safer performance.

The optimal needle size for native renal biopsies has not been established, but the most used are three: 18 gauge (internal diameter 300-400 μm), 16 gauge (internal diameter 600-700 μm) and 14 gauge (internal diameter 900-1000 μm). The first one is reserved to paediatric patients because the internal diameter of the needle is barely bigger than an adult glomerulus (200-250 pmol/L), while the other two are more appropriate for the adult patients[13,14]. On the other hand, the length of this device is almost the same and is around 20 cm.

SAMPLE ADEQUACY

The number of glomeruli is the main determinant of the biopsy adequacy but it varies based on the type of glomerular disease. For example in focal disease, such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, the diagnosis can be made by identifying even one glomerulus that presents the typical lesions but the probability to make diagnoses is directly proportional to the number of glomeruli[15]. Therefore, in a kidney in which 20% of glomeruli are sclerotic, if a bioptic sample includes five glomeruli the probability to miss affected glomeruli is about 35%. This percentage falls down to 10% if the bioptic sample includes ten glomeruli and to 1% if it includes twenty glomeruli[16,17]. Therefore, the minimum number of glomeruli required to define an adequate bioptic sample is ten, and usually, to get this target at least two different cores are taken which are divided for light microscopy (LM) (placed in formalin or another fixative), immunofluorescence (IF) (placed in transport solution-saline solution- and quickly freezed), and electron microscopy (EM) (fixed in 2%-3% glutaraldehyde or 1%-4% paraformaldehyde)[18].

Actually, the latter is not frequently and widespread performed in the practice of renal biopsy since it is possible to get a diagnosis in most cases with the contribution of the LM and the IF. However, due to the relevance of EM in some specific glomerular diseases, it has been recommended that renal tissue for EM be set aside in each case if EM cannot be performed routinely[19]. As an alternative, IF may be also performed on paraffin sample, using only one core for LM and IF and further reducing the risk of complications resulting from biopsy. The technique is certainly more complicated and needs more time for preparation but provides comparable results with the classic procedure with the exception of complement factors; consequently, it may be used in selected cases and/or in patients with greater bleeding risk.

About the optimal needle size for native renal biopsies, there is not a general consensus to achieve a good compromise between sample adequacy and lower number of complications. In adult patients a 14 or 16 gauge needle seems to be appropriate[20], while in paediatric patients it is better to use 18 gauge needles[21].

COMPLICATIONS

Even if PRB is considered a safe procedure, it is not without complications (Table 2) that, in very rare cases, may also cause death or require extreme procedures such as nephrectomy[22-24]. For this reason it is always necessary to evaluate the risk/benefit for the patient, inform him/her and obtain a signed consent. Furthermore, complications are divided into major complications that need a treatment or an intervention to stop the problem, and minor complications that spontaneously resolve without intervention or further treatment; in both cases, bleeding is the main consequence of PRB and can occur at different levels: (1) in the collecting duct system, causing micro - gross haematuria which may result in clots formation in the urine (ureter or bladder) with risk of obstructive renal failure; (2) below the kidney capsule, causing subcapsular hematoma formation that in rare cases may lead to the Page kidney, which consists in renal ischemia caused by prolonged compression of the kidney from haemorrhage with resulting arterial hypertension characterized by high renin levels[25]; and (3) in the perinephric space, causing hematoma formation which may be asymptomatic, in the majority of cases, or result into a clinically relevant complication, such as lumbar pain, significant drop in haemoglobin concentration, or need for a blood transfusion.

Table 2.

Types of complications after renal biopsy

| Minor complications | Major complications |

| Bleeding | Bleeding |

| Asymptomatic haematoma | Hematoma requiring blood transfusion or invasive procedure to stop bleeding |

| Microscopic and gross haematuria | Urinary tract obstruction with or without AKI |

| Anaemia (drop in haemoglobin concentration ≥ 1 g/dL) | Hypotension related to bleeding |

| Pain (> 12 h) | Nephrectomy |

| Page kidney | Sepsis |

| Perinephric infection | Other organs and/or blood vessels perforation |

| Arteriovenous fistula | Death |

AKI: Acute kidney injury.

However, the risk of complications after renal biopsy is not high (Table 3). In fact, in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 34 retrospective and prospective studies including 9474 adult patients who underwent biopsy of the native kidney, using ultrasound real-time imaging and automatic biopsy device, the overall incidence of bleeding complications were: Transient gross haematuria 3.5%, request for transfusion therapy 0.9%, demand on angiographic control of bleeding 0.6%, request for nephrectomy for control of bleeding 0.01% and death 0.02%[26]. Thus, the risk of using invasive procedures to stop bleeding is very rare[27,28]. More frequently we can treat this complication with medical treatment such as administration of endovenous fluid and/or blood products[29]. Moreover in some cases of persistent hemorrhage, before performing embolization of a pseudoaneurysm or surgery to stop the bleeding, we can resort to off-label drug use such as recombinant activated factor VII[30].

Table 3.

List of main studies (> 500 biopsies) reporting minor, major complications and mortality rate after renal biopsy

| Ref. | Year of publication | No. of biopsies | % Minor complications | % Major complications | % Mortality |

| Fenerberg et al[24] | 1998 | 1081 | 9.6 | 1.11 | 0.09 |

| Prasad et al[28] | 1998 | 1090 | 3 | 0.36 | 0 |

| Preda et al[20] | 2003 | 515 | 9.5 | 2.7 | 0 |

| Whittier et al[51] | 2004 | 750 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 0.13 |

| Atwell et al[44] | 2010 | 5832 | - | 0.7 | 0 |

| Stratta et al[29] | 2007 | 1137 | 24.2 | 0.36 | 0 |

| Korbet et al[23] | 2014 | 1055 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 0.09 |

| Mai et al[21] | 2013 | 934 | 5.9 | 0.86 | 0 |

| Tøndel et al[13] | 2012 | 9288 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 0 |

| Prasad et al[28] | 2015 | 2138 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 0 |

Specific symptoms and signs post-biopsy

Lumbar pain: The pain is an extremely common consequence of PRB and usually occurs at the end of anaesthesia. If necessary it is possible to administer a mild analgesic. Otherwise, the onset of greater pain suggests the development of a major complication and further diagnostic tests must be performed.

Microscopic haematuria: It is the most common consequence of this procedure; it is usually asymptomatic[31] and resolves spontaneously over a few days.

Gross haematuria: It occurs in 3% of renal biopsies and typically disappears in few hours or days. Occasionally gross haematuria may cause a significant drop in haemoglobin concentration requiring a blood transfusion or, in rare cases, it may result in clots formation with or without obstructive renal failure. On the contrary, persistent haematuria after three days suggests the onset of major complications such as arteriovenous fistula (AVF)[32].

Acute anaemia: A decrease of haemoglobin concentration ≥ 1 g/dL occurs in more than 50% of uncomplicated renal biopsies[33], whereas a fall ≥ 2 g/dL occurs in 10% of uncomplicated cases and is consequently associated with increased risk of complications[34].

Perinephric hematoma: The presence of asymptomatic hematoma is frequently detected during a renal ultrasound after biopsy and does not constitute per se a complication. Prospective studies showed that perinephric hematoma is detectable in 90% of patients 24-72 h after the procedure, while this percentage drops to 15% immediately after the biopsy. Most of the perinephric hematomas are small, asymptomatic and they resolve spontaneously in few months; only in 2% of cases they may cause a clinically relevant complication such as lumbar pain, a decrease in haemoglobin concentration, or the need for blood transfusion. However, the absence of hematoma at 1 h was highly predictive of an uncomplicated course[35].

Waldo et al[36] showed that patients which did not present perinephric hematoma one hour after biopsy did not develop major complications in 95% of cases, while the presence of hematoma was predictive for major complications in 43%. Therefore, the routine use of ultrasound at 1 h after PRB may have a role in determining an uncomplicated course[36].

AVF: It is not a frequent complication and is due to trauma of the wall of blood vessels; it is clinically asymptomatic and resolves spontaneously in most cases[37]. In rare cases AVF can cause the development of an aneurysm, which may manifest clinically with high blood pressure, heart failure, and kidney failure. Important signs that suggest this complication are the persistence of gross haematuria, the presence of abdominal bruit and palpable trill[38,39] but diagnosis confirmation requires Doppler ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging, or angiography. The treatment of symptomatic cases is based on superselective transcatheter arterial embolization or, in rare cases, surgery[40].

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND RISK FACTORS

Contraindications to renal biopsy and risk factors must be taken into account to minimize the risk of complications.

The presence of intravascular coagulopathy, polycystic kidneys, obstruction of the urinary tract, hydronephrosis, infections of the upper urinary tract are regarded as absolute contraindications. Otherwise, there are some conditions, which require caution, considered as relative contraindications, such as compromised cardiopulmonary function or hemodynamic instability, severe obesity, inability of the patient to cooperate, solitary kidney, advanced age, severe hypertension (> 160/95 mmHg), and renal failure[41]. The last one causes functional alterations of coagulation factors as the von Willebrand factor (vWF) and the Factor VIII, abnormalities in platelet membrane, accumulation of uremic toxins that inhibit platelet aggregation, high levels of prostacyclin and nitric oxide which are factors that reduce platelet aggregation. Another element that often contributes to increase the risk of bleeding in renal failure is the presence of anaemia. Other diseases associated with greater risk of bleeding are those with arteriolar involvement as SLE, vasculitis, scleroderma, amyloidosis and advanced diabetic nephropathy because they interfere with the first mechanism of haemostasis, known as the vascular phase, reducing the arteriolar contraction.

PROCEDURES PRE-BIOPSY

Before performing the PRB it is very important to follow some recommendations to minimize the risk of complications. Renal ultrasound is essential to evaluate the presence of anatomical abnormalities of the kidney (presence of multiple cysts, hydronephrosis, solitary kidney) that may represent a risk factor for the development of complications.

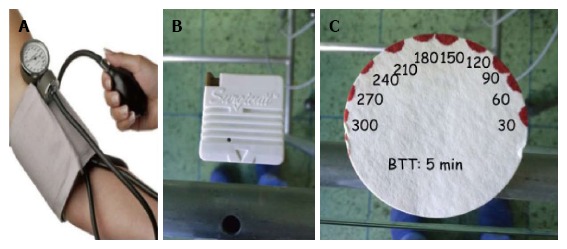

Laboratory tests may reveal the potential presence of coagulopathy. To totally assess the steps of haemostasis it is useful to use the bleeding time that evaluates the time of platelet aggregation (Figure 2). In case of advanced renal failure and/or prolonged bleeding time, the administration of desmopressin acetate - DDAVP (0.3 μg/kg), estrogen and cryoprecipitate has shown a reduction of the bleeding risk[42,43].

Figure 2.

Bleeding time procedure. A: Place the sphygmomanometer on the upper arm and inflate to 40 mmHg; B: Make a small cut on the lower arm with automatic standard device; C: Blotting paper is used to draw off the blood every 30 s (normal range 3-7 min).

Antiplatelet agents and oral anticoagulants have to be withdrawn at least one week before renal biopsy[44], the last ones until normalization of INR, and replaced with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). Other drugs that may cause alterations in coagulation are the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which should be not taken for at least 5 d before PRB.

ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES FOR RENAL BIOPSY

In some cases, PRB may be contraindicated because of bleeding diatheses or habitus of the patients such as obesity. In these circumstances we can perform renal biopsy with alternative methods such as under CT guidance[45] or with laparoscopic[46] and transjugular approach[47]. These techniques may have some limits. CT guidance, for example, does not assess any possible movements of the kidney related to breathing, laparoscopic biopsy requires general anaesthesia and transjugular biopsy seems to be associated with a lower diagnostic power due to the need to pass through the medulla first[48].

In obese patients a new approach of PRB under real-time ultrasound guidance has been proposed with the patient in supine antero-lateral position (SALP). Gesualdo et al[49] reported a case series of 110 patients undergoing PRB, divided into two groups: Low risk group (90 patients) if the body mass index (BMI) was ≤ 30 in the absence of respiratory disorders and high risk group (20 patients) if BMI was > 30 with breathing problems. The first group underwent classical PRB in prone position and the other group in SALP, demonstrating, at the end of the study, that there were no substantial differences about adequacy samples and patients safety[49]. Moreover, an open renal biopsy may be performed when uncorrectable contraindications are present. Nomoto et al[50] reported 931 cases of open kidney biopsies concluding that this is a safe procedure with 100% of sample adequacy but an important limitation of this technique is the use of general anesthesia.

PERIOD OF OBSERVATION

After biopsy, the patient must be at rest for at least 6-8 h in the supine position. Blood pressure should be monitored frequently, and urine must be checked to evaluate the presence of gross haematuria. If there are no signs of bleeding within 6 h, the patient may sit up, because most of complications occur within 6-8 h. However, since some complications may also occur later, the ideal observation time should be continued for 24 h. In a case series of 750 biopsies of native kidney it was reported that 67% of major complications appeared within the first 8 h, suggesting that observation for 24 h is safer in renal biopsy[51].

CONCLUSION

PRB is a safe procedure and the risk of development of major complications is very rare. Instead, the minor consequences due to the procedure occour more frequently. These are micro- and/or gross haematuria, drop in hemoglobin concentration > 1 g/dL, development of asymptomatic perinephric hematoma. All these minor adverse events can be more safely managed and do not bring particular complications to the patient. It is mandatory to identify risk factors for bleeding such as anaemia, prolonged bleeding time or advanced renal failure, severe arterial hypertension and correct them when possible; where this is not possible, it is recommended to postpone the procedure.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest. No financial support.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 13, 2016

First decision: March 1, 2016

Article in press: April 6, 2016

P- Reviewer: Bosch RJ, Fujigaki Y, Rydzewski A, Watanabe T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Cohen AH, Nast CC, Adler SG, Kopple JD. Clinical utility of kidney biopsies in the diagnosis and management of renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1989;9:309–315. doi: 10.1159/000167986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korbet SM. Percutaneous renal biopsy. Semin Nephrol. 2002;22:254–267. doi: 10.1053/snep.2002.31713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edebohls GM. The surgical treatment of Bright’s disease. Am J Med Sci. 1905;129:708. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iversen P, Roholm K. On aspiration biopsy of the liver, with remarks on its diagnostic significance. Acta Med Scand. 1939;102:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alwall N. Aspiration biopsy of the kidney, including i.a. a report of a case of amyloidosis diagnosed through aspiration biopsy of the kidney in 1944 and investigated at an autopsy in 1950. Acta Med Scand. 1952;143:430–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iversen P, Brun C. Aspiration biopsy of the kidney. Am J Med. 1951;11:324–330. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(51)90169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kark RM, Muehrcke RC. Biopsy of kidney in prone position. Lancet. 1954;266:1047–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(54)91618-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tape TG, Wigton RS, Blank LL, Nicolas JA. Procedural skills of practicing nephrologists. A national survey of 700 members of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:392–397. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-5-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane C, Brown M. Alignment of nephrology training with workforce, patient, and educational needs: an evidence based proposal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2681–2687. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02230311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whittier WL, Korbet SM. Who should perform the percutaneous renal biopsy: a nephrologist or radiologist? Semin Dial. 2014;27:243–245. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amore A, on Behalf of the ESPN Immune Mediated WG and the ERA-ETDA Immunonephrology WG. European survey on renal biopsy (RB) procedures in adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(suppl 3):iii104–iii105. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birnholz JC, Kasinath BS, Corwin HL. An improved technique for ultrasound guided percutaneous renal biopsy. Kidney Int. 1985;27:80–82. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tøndel C, Vikse BE, Bostad L, Svarstad E. Safety and complications of percutaneous kidney biopsies in 715 children and 8573 adults in Norway 1988-2010. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1591–1597. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02150212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker PD. The renal biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:181–188. doi: 10.5858/133.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corwin HL, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. The importance of sample size in the interpretation of the renal biopsy. Am J Nephrol. 1988;8:85–89. doi: 10.1159/000167563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoy WE, Samuel T, Hughson MD, Nicol JL, Bertram JF. How many glomerular profiles must be measured to obtain reliable estimates of mean glomerular areas in human renal biopsies? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:556–563. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang HJ, Kjellstrand CM, Cockfield SM, Solez K. On the influence of sample size on the prognostic accuracy and reproducibility of renal transplant biopsy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:165–172. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker PD, Cavallo T, Bonsib SM. Practice guidelines for the renal biopsy. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1555–1563. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haas M. A reevaluation of routine electron microscopy in the examination of native renal biopsies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:70–76. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V8170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preda A, Van Dijk LC, Van Oostaijen JA, Pattynama PM. Complication rate and diagnostic yield of 515 consecutive ultrasound-guided biopsies of renal allografts and native kidneys using a 14-gauge Biopty gun. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:527–530. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mai J, Yong J, Dixson H, Makris A, Aravindan A, Suranyi MG, Wong J. Is bigger better? A retrospective analysis of native renal biopsies with 16 Gauge versus 18 Gauge automatic needles. Nephrology (Carlton) 2013;18:525–530. doi: 10.1111/nep.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang CC, Kuo CC, Chen YM. The incidence of fatal kidney biopsy. Clin Nephrol. 2011;76:256–258. doi: 10.5414/cnp76256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korbet SM, Volpini KC, Whittier WL. Percutaneous renal biopsy of native kidneys: a single-center experience of 1,055 biopsies. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39:153–162. doi: 10.1159/000358334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feneberg R, Schaefer F, Zieger B, Waldherr R, Mehls O, Schärer K. Percutaneous renal biopsy in children: a 27-year experience. Nephron. 1998;79:438–446. doi: 10.1159/000045090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCune TR, Stone WJ, Breyer JA. Page kidney: case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;18:593–599. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corapi KM, Chen JL, Balk EM, Gordon CE. Bleeding complications of native kidney biopsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:62–73. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.02.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hergesell O, Felten H, Andrassy K, Kühn K, Ritz E. Safety of ultrasound-guided percutaneous renal biopsy-retrospective analysis of 1090 consecutive cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:975–977. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.4.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad N, Kumar S, Manjunath R, Bhadauria D, Kaul A, Sharma RK, Gupta A, Lal H, Jain M, Agrawal V. Real-time ultrasound-guided percutaneous renal biopsy with needle guide by nephrologists decreases post-biopsy complications. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:151–156. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stratta P, Canavese C, Marengo M, Mesiano P, Besso L, Quaglia M, Bergamo D, Monga G, Mazzucco G, Ciccone G. Risk management of renal biopsy: 1387 cases over 30 years in a single centre. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:954–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maksimovic B, Neretljak I, Vidas Z, Vojtusek IK, Tomulic K, Knotek M. Treatment of bleeding after kidney biopsy with recombinant activated factor VII. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2012;23:241–243. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835029a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altebarmakian VK, Guthinger WP, Yakub YN, Gutierrez OH, Linke CA. Percutaneous kidney biopsies. Complications and their management. Urology. 1981;18:118–122. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(81)90418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergman SM, Frentz GD, Wallin JD. Ureteral obstruction due to blood clot following percutaneous renal biopsy: resolution with intraureteral streptokinase. J Urol. 1990;143:113–115. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39884-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolton WK. Nonhemorrhagic decrements in hematocrit values after percutaneous renal biopsy. JAMA. 1977;238:1266–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khajehdehi P, Junaid SM, Salinas-Madrigal L, Schmitz PG, Bastani B. Percutaneous renal biopsy in the 1990s: safety, value, and implications for early hospital discharge. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34:92–97. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alter AJ, Zimmerman S, Kirachaiwanich C. Computerized tomographic assessment of retroperitoneal hemorrhage after percutaneous renal biopsy. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:1323–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waldo B, Korbet SM, Freimanis MG, Lewis EJ. The value of post-biopsy ultrasound in predicting complications after percutaneous renal biopsy of native kidneys. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2433–2439. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rollino C, Garofalo G, Roccatello D, Sorrentino T, Sandrone M, Basolo B, Quattrocchio G, Massara C, Ferro M, Picciotto G. Colour-coded Doppler sonography in monitoring native kidney biopsies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9:1260–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang CY, Lai MY, Lu CL, Tseng HS, Chiou HJ, Yang WC, Ng YY. Timing of Doppler examination for the detection of arteriovenous fistula after percutaneous renal biopsy. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36:377–380. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alcázar R, de la Torre M, Peces R. Symptomatic intrarenal arteriovenous fistula detected 25 years after percutaneous renal biopsy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:1346–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Güneyli S, Gök M, Bozkaya H, Çınar C, Tizro A, Korkmaz M, Akın Y, Parıldar M, Oran İ. Endovascular management of iatrogenic renal arterial lesions and clinical outcomes. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2015;21:229–234. doi: 10.5152/dir.2014.14286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eiro M, Katoh T, Watanabe T. Risk factors for bleeding complications in percutaneous renal biopsy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2005;9:40–45. doi: 10.1007/s10157-004-0326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedges SJ, Dehoney SB, Hooper JS, Amanzadeh J, Busti AJ. Evidence-based treatment recommendations for uremic bleeding. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3:138–153. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kropp KA, Shapiro RS, Jhunjhunwala JS. Role of renal biopsy in end stage renal failure. Urology. 1978;12:631–634. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(78)90421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atwell TD, Smith RL, Hesley GK, Callstrom MR, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Charboneau JW, Welch TJ. Incidence of bleeding after 15,181 percutaneous biopsies and the role of aspirin. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:784–789. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kudryk BT, Martinez CR, Gunasekeran S, Ramirez G. CT-guided renal biopsy using a coaxial technique and an automated biopsy gun. South Med J. 1995;88:543–546. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gimenez LF, Micali S, Chen RN, Moore RG, Kavoussi LR, Scheel PJ. Laparoscopic renal biopsy. Kidney Int. 1998;54:525–529. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fine DM, Arepally A, Hofmann LV, Mankowitz SG, Atta MG. Diagnostic utility and safety of transjugular kidney biopsy in the obese patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:1798–1802. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mal F, Meyrier A, Callard P, Kleinknecht D, Altmann JJ, Beaugrand M. The diagnostic yield of transjugular renal biopsy. Experience in 200 cases. Kidney Int. 1992;41:445–449. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gesualdo L, Cormio L, Stallone G, Infante B, Di Palma AM, Delli Carri P, Cignarelli M, Lamacchia O, Iannaccone S, Di Paolo S, et al. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided renal biopsy in supine antero-lateral position: a new approach for obese and non-obese patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:971–976. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nomoto Y, Tomino Y, Endoh M, Suga T, Miura M, Nomoto H, Sakai H. Modified open renal biopsy: results in 934 patients. Nephron. 1987;45:224–228. doi: 10.1159/000184122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whittier WL, Korbet SM. Timing of complications in percutaneous renal biopsy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:142–147. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000102472.37947.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]