Abstract

In Staphylococcus aureus, metabolism is intimately linked with virulence determinant biosynthesis, and several metabolite-responsive regulators have been reported to mediate this linkage. S. aureus possesses at least three members of the RpiR family of transcriptional regulators. Of the three RpiR homologs, RpiRc is a potential regulator of the pentose phosphate pathway, which also regulates RNAIII levels. RNAIII is the regulatory RNA of the agr quorum-sensing system that controls virulence determinant synthesis. The effect of RpiRc on RNAIII likely involves other regulators, as the regulators that bind the RNAIII promoter have been intensely studied. To determine which regulators might bridge the gap between RpiRc and RNAIII, sarA, sigB, mgrA, and acnA mutations were introduced into an rpiRc mutant background, and the effects on RNAIII were determined. Additionally, phenotypic and genotypic differences were examined in the single and double mutant strains, and the virulence of select strains was examined using two different murine infection models. The data suggest that RpiRc affects RNAIII transcription and the synthesis of virulence determinants in concert with σB, SarA, and the bacterial metabolic status to negatively affect virulence.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a major human pathogen causing a diverse range of infections, from superficial skin and wound infections to life-threatening diseases such as bacteremia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, deep tissue abscesses, or pneumonia (1). The pathogenicity of S. aureus is due in part to its ability to produce a large number of virulence determinants, including secreted proteins (e.g., toxins and proteases), cell wall-associated proteins (e.g., protein A and fibronectin binding proteins), and extracellular polysaccharides (i.e., capsule and polysaccharide intercellular adhesion). During colonization and infection of a host, S. aureus must adapt to rapidly changing environmental and nutritional conditions by coordinating the transcription and translation of physiologic and virulence genes (2). To coordinately control these cellular processes, S. aureus has evolved or acquired a network of regulators such as the recently identified family of proteins, RpiR, that affect pentose phosphate pathway activity and virulence determinant synthesis (3).

Central to the regulatory network is the accessory gene regulator (Agr) system, a regulator of virulence determinant synthesis that responds to the bacterial population density (4). The agr locus consists of two divergent transcriptional units, RNAII and RNAIII, driven by the P2 and P3 promoters, respectively. RNAII comprises the agrBDCA operon, of which the agrBD gene products are involved in the synthesis, transport, and maturation of an autoinducing peptide (AIP). As the cell density increases, AIP accumulates in the extracellular milieu and when a threshold is achieved the two-component system AgrCA responds by activating transcription of both P2 and P3 promoters. The P3 promoter drives transcription of RNAIII, which is the regulatory effector of the Agr system and the mRNA that codes for delta-toxin. RNAIII reduces the expression of several cell surface proteins and activates the synthesis of many secreted proteins and capsule at the transcriptional and/or translational level.

The Staphylococcus accessory gene regulator, SarA, is a small DNA- and RNA-binding protein that originates from three overlapping transcripts initiated by individual promoters (5, 6). SarA also regulates transcription of many S. aureus virulence genes and functions in part by activating the agr promoters (5, 7–10). Regulation of virulence gene transcription by SarA involves direct binding of the protein to an AT-rich DNA motif (11); however, the molecular mechanisms remain unclear (10, 12–15). Both the agr and the sarA loci have been closely linked to the ability of S. aureus to invade and survive within a host, and mutants in either regulatory system are attenuated in virulence (16–22). In addition to SarA, there is another MarR protein family member called MgrA, which is a pleiotropic regulator that controls about 350 genes (23) affecting autolysis (24), antibiotic resistance (25), virulence determinants (26), and pathogenicity (27, 28). The activity of MgrA is mediated by a redox-switch and through interactions with other regulatory elements (23, 27, 29, 30). A number of other members of the MarR/SarA protein family such as Rot, SarS, SarR, SarU, and SarT have been identified as being involved in agr and sarA regulation (31).

The alternative sigma factor B (σB) regulates transcription of genes involved in the stress response that contribute to survival under unfavorable conditions like heat, oxidative, and antibiotic stresses (32–35). In addition, the sigB operon is linked to the complex network of virulence determinant regulation in S. aureus by altering transcription of sarA and RNAIII (36–41).

Inactivation of central metabolic pathways, such as the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, can affect virulence determinant biosynthesis by feedback and feedforward alteration of enzymatic activity or by altering the intracellular concentrations of metabolites to which metabolite-responsive regulators respond (42–46). Several metabolite-responsive regulators have been identified in S. aureus (e.g., CcpA [47, 48], CodY [49, 50], CcpE [51, 52], and Rex [53]) that link metabolism with virulence regulation. As examples, the carbon catabolite protein A (CcpA) responds to glucose-associated metabolic signals (54), whereas CodY responds to GTP and branched-chain amino acids (50, 55). As mentioned, we recently identified a putative metabolite-responsive family of regulators in S. aureus, RpiR, which contain a DNA-binding helix-turn-helix motif and a sugar isomerase binding domain (3). Inactivation of the rpiRc gene in S. aureus strain UAMS-1 dramatically increased the transcription and/or stability of RNAIII (3). To determine whether the effect of rpiRc inactivation on RNAIII levels required one or more of the known regulators of RNAIII transcription, we constructed agr, sigB, sarA, and mgrA regulatory mutants and an aconitase (acnA) mutant in strain SA564 and its isogenic rpiRc deletion mutant. The effects of these mutations on growth, cultivation pH profiles, and the transcription of RNAIII, spa (encoding protein A), hla (encoding alpha-hemolysin or alpha-toxin), and capA (encoding the initial capsule biosynthesis enzyme) were determined. In addition, the in vivo importance of RpiRc was assessed in chronic and acute murine infection models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, materials, and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. aureus strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) containing 0.25% glucose or on TSB plates containing 1.5% agar (TSA). Unless otherwise indicated, antibiotics were only used for strain construction and phenotypic selection at the following concentrations: tetracycline, 2.5 μg/ml; erythromycin, 2.5 μg/ml; kanamycin, 15 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 10 μg/ml. To inoculate cultures, bacteria from an overnight culture were inoculated 1:200 into TSB, cultured for 1.5 to 2 h, and harvested by centrifugation (5 min, 5,000 rpm), and the bacteria were diluted to an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 in fresh medium. Bacterial cultures were grown with shaking at 225 rpm at 37°C, using a flask-to-medium ratio of 10:1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus strains | ||

| SA564 | S. aureus clinical isolate, wild type | 89 |

| BS687 | RN6734 hldagrBDCA::ermB | Bo Shopsin |

| CYL1050 | Newman mgrA::cat | 26 |

| UAMS-1 | UAMS-1 sarA::kan | 69 |

| HOM15 | COL rsbUVW sigB::ermB | 34 |

| SA-rpiRc | SA564 rpiRc::tetM | 3 |

| SA-rpiRc_rpiRc | SA564 rpiRc::tetM_pEC-rpiRc; cis-complemented SA-rpiRc mutant | This study |

| SA-acnA | SA564 acnA::ermB | 44 |

| SA-acnA rpiRc | SA564 acnA::ermB rpiRc::tetM | This study |

| SA-agr | SA564 hldagrBDCA::ermB | This study |

| SA-agr rpiRc | SA564 hldagrBDCA::ermB rpiRc::tetM | This study |

| SA-mgrA | SA564 mgrA::cat | This study |

| SA-mgrA rpiRc | SA564 mgrA::cat rpiRc::tetM | This study |

| SA-sarA | SA564 sarA::kan | This study |

| SA-sarA rpiRc | SA564 sarA::kan rpiRc::tetM | This study |

| SA-sigB | SA564 rsbUVW sigB::ermB | This study |

| SA-sigB rpiRc | SA564 rsbUVW sigB::ermB rpiRc::tetM | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEC4 | pBluescript II KS(+) with ermB inserted into the ClaI site | 90 |

| pSB2035 | E. coli-S. aureus shuttle plasmid, luciferase reporter system of the agr P3 promoter; Cmr | 58 |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance.

Phage transduction.

Mutants of strains SA564 and SA-rpiR were constructed by phage transduction. Briefly, donor strains were grown overnight in TSB at 37°C using a flask/medium ratio of 10:1 and with shaking at 225 rpm. The cultures were supplemented with CaCl2 to a final concentration of 5 mM, and aliquots were infected with serial dilutions of transducing phage ϕ11, 80α, and/or ϕ85 and distributed on TSA plates using lysogeny broth medium with 0.6% agar containing 5 mM CaCl2. After confluent lysis of the bacterial cells, the phage lysate was harvested and used to transfer mutations into recipient strains.

RNA isolation and purification.

S. aureus strains were grown as described. Bacteria were harvested after 2, 4, 6, or 8 h cultivation by mixing with an equal volume of killing buffer (20 mM Tris/HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM NaN3) and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min. Total RNA was isolated from the pelleted bacteria using the FastRNA Pro Blue kit (Qbiogene) and was further purified using an RNeasy kit with on-column DNase treatment (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Alternatively, bacteria were lysed in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) with 0.5 ml of zirconia-silica beads (0.1 mm in diameter) in a high-speed homogenizer (Savant Instruments, Farmingdale, NY). RNA was isolated as described in the instructions provided by the manufacturer of TRIzol. RNA concentrations were determined from the absorbance at 260 nm, and the RNA was examined by agarose gel electrophoresis to assess the quality.

Complementation of rpiRc mutant.

Plasmid pEC4 containing an erythromycin resistance gene (ermB) and an ampicillin resistance gene (bla) was used to complement rpiRc mutants in cis. Briefly, the rpiRc gene from S. aureus strain SA564 was amplified by PCR using the primers MBH-467_SAV2315_compl-f and MBH-468_SAV2315_compl-r and was ligated into pEC4 after restriction with EcoRI and BamHI. The resulting plasmid, pEC4-rpiRc, was transformed into Escherichia coli strain DH5α and after isolation and verification electroporated into S. aureus strain RN4220. The plasmid was integrated into the chromosome via a single cross over and the region containing an intact rpiRc gene was phage transduced from RN4220 into the rpiRc mutant strains. Integration was verified by erythromycin selection and PCR using primer pairs ermB-int-+/ermB-int- and ermB-int-+/SAV2315_C_r (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

The Turbo DNA-free DNase treatment and removal kit (Ambion) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to eliminate residual DNA contamination from total RNA preparations. RNA concentrations were determined from the absorbance at 260 nm, and the absence of chromosomal DNA was assessed by PCR and control reactions without reverse transcriptase (RT) during cDNA synthesis. DNA-free total RNA was synthesized to cDNA using the Bio-Rad iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantification of mRNA was performed using the Bio-Rad CFX Connect real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) with 20-μl PCR mixtures containing Bio-Rad SsoAdvanced SybrGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad), gene-specific primer pairs listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material, and diluted cDNA template. No-template and no-RT controls were routinely analyzed with the test reactions. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 3 min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 25 s at 60°C, and 20 s at 72°C, and single amplification products were verified by subsequent melting curve analysis. The increase in fluorescence was used to monitor amplification, and the threshold cycle (CT) number was determined. Standard curves were generated for each primer pair to determine the amplification efficiency using serial dilutions of pooled cDNA samples and the Bio-Rad CFX Manager 2.1 software. These PCR efficiency values were applied in the subsequent calculation of relative mRNA levels for each gene. The transcriptional levels of target genes were normalized against the mRNA concentration of 16S rRNA and gyrB reference genes according to the ΔΔCT method and scaled to the geometric mean of all samples. Samples were assayed at least in duplicate from three independent biological replicates.

Northern blot analysis.

For Northern blot analysis, total RNA isolated from bacterial cultures was transferred to a positively charged membrane after electrophoresis as described previously (56). The intensities of the 23S and 16S rRNA bands stained by ethidium bromide were verified to be equivalent in all the samples before transfer. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes for the detection of specific transcripts were generated using a DIG-labeling PCR kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Biochemicals).

Hemolytic activity.

The hemolytic activity of S. aureus strains was assessed qualitatively by growth on rabbit blood agar plates and evaluation of the lytic zones after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Additionally, a microplate hemolytic assay using rabbit erythrocytes was performed. Twofold serial dilutions of 12-h culture supernatants in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) were mixed with an equal volume (100 μl) of 2% (vol/vol) washed rabbit erythrocytes in PBS in 96-well U-bottom microtiter plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by further incubation at 4°C overnight. The microtiter plate was centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min. The hemolytic activity titer was defined as the inverse of the last dilution that caused complete hemolysis.

Western blot analyses.

To determine the effects of gene inactivation on protein A biosynthesis, the culture supernatants of S. aureus strains were collected, and optical density at 600 nm (OD600)-adjusted aliquots were subjected to Western blot analysis as described previously (3).

Capsule immunoblot assay.

The accumulation of capsule was quantified as described previously (26, 57). Briefly, equivalent numbers of bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and suspended in PBS and then treated with DNase I, lysostaphin, and proteinase K. After heat inactivation of the enzyme, serial dilutions of the crude extracts were assayed by immunoblotting.

Luciferase activity assay.

RNAII transcription from the P3 promoter in S. aureus strains was examined by monitoring the luciferase activity produced by the agr-lux reporter plasmid pSB2035 (58). Bacteria were cultivated as described previously using medium containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. At the indicated time, bacterial aliquots (100 μl) were transferred in a black 96-well microtiter plate, and relative light unit readings were taken for 5 s at 37°C in a Wallac Victor2 1420 multilabel counter (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences). A control sample of the wild type without plasmid was included to allow for background luminescence correction. For each sample, luciferase activity was normalized to the OD600.

Murine infection models.

All animal experiments were approved by the local State Review Boards of Saarland following the national guidelines for the ethical and humane treatment of animals.

Bacterial strains were grown overnight in TSB at 37°C, diluted to an initial OD600 of 0.05 in fresh medium, and incubated at 37°C with a flask/medium ratio of 10:1 with 225-rpm aeration for 2 h. Bacteria from the exponential growth phase were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and suspended in sterile PBS. Bacterial suspensions were diluted to the desired OD600 representing the correct infectious dose, which was validated by determining the colony formation on sheep blood agar plates. Female, 8- to 10-week-old C57/BL6N mice were used and maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions.

For the systemic abscess model (47), 100-μl bacterial suspensions containing 107 CFU were administered intravenously by retro-orbital injection into mice anesthetized by the intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg of ketamine hydrochloride (Pfizer, Berlin, Germany)/kg body weight and 10 mg of xylazine hydrochloride (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany)/kg. At 4 days postinfection, the mice were sacrificed, and the kidneys and livers were removed. Portions of the liver and left kidney were fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. From each organ, 5-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) according to standard protocols and analyzed by light microscopy. The remainders of each liver and right kidney were weight adjusted and homogenized in PBS, and serial dilutions of the homogenates were plated on sheep blood agar plates to enumerate the CFU.

In the lung infection model (59, 60), anesthetized mice were infected intranasally with 2.5 × 108 or 1 × 108 CFU of S. aureus. At 24 h postinfection, the animals were sacrificed, and a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed before removal of the entire lung. To determine the bacterial load in the lung, serial dilutions of BAL and lung homogenates were plated on blood agar plates, and the CFU were determined. For statistical analysis, nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests were performed using Prism (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

Inactivation of rpiRc pleiotropically affects transcription and accumulation of virulence determinants via the agr and sarA regulatory loci.

To determine whether the stimulatory effect of rpiRc inactivation on RNAIII levels was mediated by one of the established RNAIII regulators, double mutants were constructed (Table 1), and the effects on growth, virulence determinant transcription, and biosynthesis were assessed. Consistent with previous observations (3), inactivation of rpiRc in strain SA564 slightly altered growth in the postexponential growth phase (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Interestingly, inactivation of agr and sarA in SA-rpiRc restored postexponential growth to wild-type levels. The restoration of growth is likely due to a redirection of carbon and energy from virulence determinant synthesis into biomass generation, but this requires further validation. In contrast to inactivation of agr and sarA, inactivation of mgrA and sigB in the SA-rpiRc mutant strain did not alter growth relative to the single mutant SA-rpiRc strain. Likewise, inactivation of acnA in strain SA-rpiRc further decreased the growth yield relative to acnA single mutant strain SA-acnA.

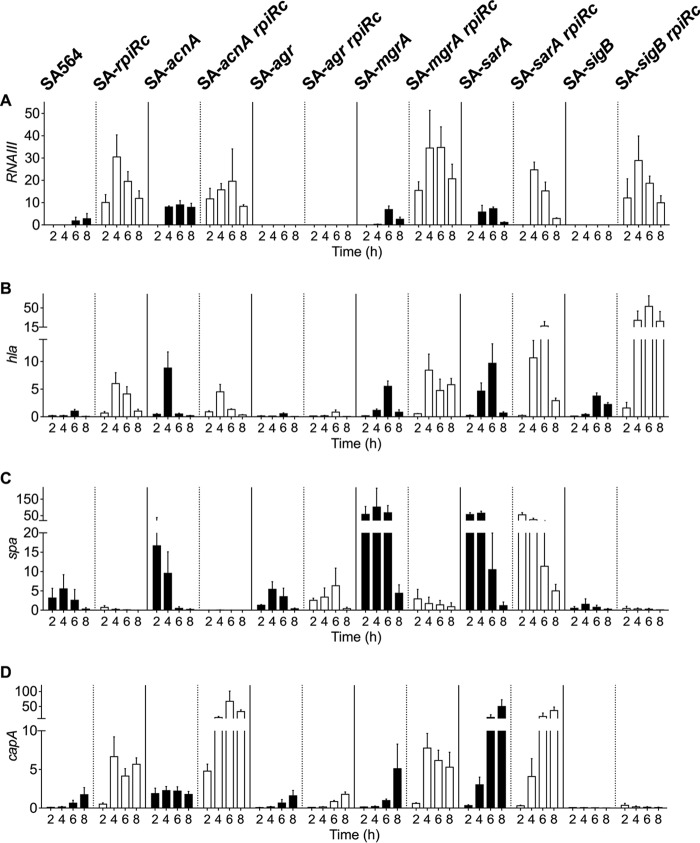

In agreement with previous observations (3), inactivation of rpiRc dramatically increased RNAIII levels in strain SA564, which is consistent with increased hla and capA mRNA levels and decreased spa mRNA (Fig. 1). These transcriptional changes were lost upon inactivation of either agr or sarA, suggesting that the effect of RpiRc on transcription is indirectly mediated through these global regulators. In contrast to the SA-agr rpiRc and SA-sarA rpiRc double-mutant strains, the high RNAIII levels in SA-rpiRc were independent of σB, MgrA, and TCA cycle activity. In contrast to previous observations reporting a negative regulatory effect of σB on RNAIII transcription (37, 61), RNAIII transcription was also abolished in the SA-sigB mutant (Fig. 1A). Although the effects of RpiRc on RNAIII were independent of σB and TCA cycle activity, a synergistic positive effect of RpiRc and σB on hla mRNA levels was observed (Fig. 1B). Similarly, inactivation of rpiRc and acnA dramatically increased capA mRNA levels, most likely due to a redirection of carbon away from the TCA cycle and into capsule biosynthesis (62) (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Effect of rpiRc mutation on transcription of RNAIII (A) and genes encoding the virulence determinants alpha-toxin (B), protein A (C), and capsule (D) throughout the growth cycle. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses of total RNA isolated from S. aureus strain SA564, isogenic single mutants of acnA, agr, mgrA, sarA, and sigB (black bars), and their respective rpiRc double mutants (white bars) cultivated for the indicated times were performed. The relative transcript levels of target genes were normalized to gyrB and 16S rRNA. Shown are the mean and standard deviation (SD) for at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

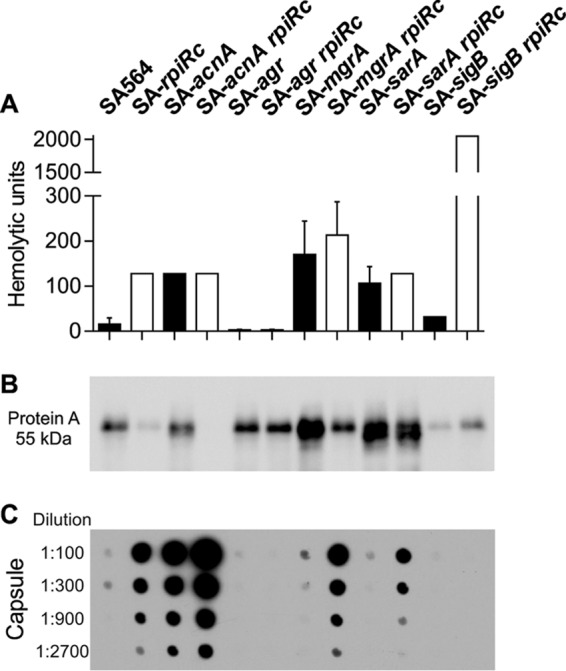

To determine whether the transcriptional changes (Fig. 1) correlate with phenotypes, the accumulation of important virulence determinants was investigated. The hemolytic activity of SA-rpiRc was approximately 12 times greater than that of the wild-type strain SA564 and comparable to single and rpiRc double mutants of acnA, mgrA, or sarA. As expected, both agr mutants had no hemolytic activity, whereas the SA-sigB rpiRc mutant had increased hemolytic activity (Fig. 2A), which was consistent with the transcriptional data for hla (Fig. 1B). In agreement with observations from S. aureus strain UAMS-1 (3), protein A was minimally synthesized in the rpiRc mutant of strain SA564, which also had greatly reduced spa mRNA levels. The negative effect of rpiRc inactivation on spa transcription or mRNA stability was abrogated by inactivation of the sar locus. In addition, spa transcription or mRNA stability and protein A accumulation were strongly decreased in the SA-sigB mutant and SA-sigB rpiRc double mutants (Fig. 1C and Fig. 2B). Similar to previous observations using strain UAMS-1 (3), inactivation of rpiRc tremendously increased the elaboration of capsule in SA564 (Fig. 2C). Importantly, these data demonstrate that the effects of rpiRc inactivation on virulence determinants are independent of the genetic background. In addition to RpiRc regulating capsule accumulation, capsule biosynthesis requires TCA cycle activity (62). Consistent with high capA mRNA levels in the exponential growth phase (Fig. 1D), the TCA cycle mutant strain SA-acnA showed increased capsule accumulation after 4 h of cultivation. An SA-rpiRc acnA double mutant had strongly increased capsule accumulation, indicating a synergistic repressive effect of RpiRc and TCA cycle activity on capsule biosynthesis. Inactivation of the global regulator mgrA had no effect on capsule accumulation in strain SA-rpiRc, whereas inactivation of sarA clearly reduced the amount of capsule detected, although it was still markedly higher than in the wild-type strain. No capsule was detected in the agr and sigB mutant pairs, highlighting the importance of these two regulators for capsule formation. Taken together, inactivation of rpiRc in S. aureus increased hemolytic activity, decreased protein A synthesis, and increased capsule synthesis, and these effects were partly mediated via the agr and sarA loci.

FIG 2.

Phenotypic characterization of virulence determinants in S. aureus regulatory mutants. S. aureus strain SA564, isogenic single mutants of acnA, agr, mgrA, sarA, and sigB, and their respective rpiRc double mutants were assayed for hemolytic activity (A), protein A accumulation (B), and capsule (C). In panel A, the means and standard deviations (SD) for at least three independent experiments are shown. In panel B, the Western blot is representative of at least three independent experiments. In panel C, the capsule immunoblot is representative of at least three independent experiments.

Exponential growth phase transcription of the agr operon is increased in the rpiRc mutant in a SarA-dependent manner.

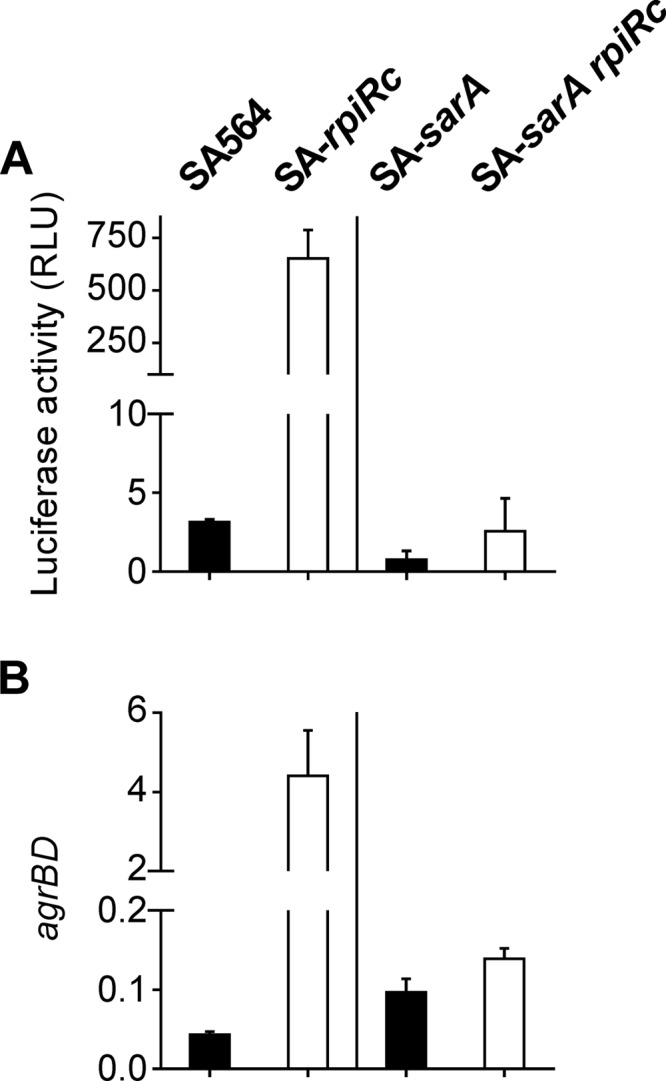

Inactivation of rpiRc in S. aureus strain SA564 increased RNAIII levels throughout the growth cycle. The exponential growth phase accumulation of RNAIII was abolished when sarA was inactivated, suggesting that SarA is required for the early accumulation of RNAIII in an rpiRc mutant (Fig. 1A). There are two possible explanations for the SarA-dependent increase in RNAIII levels; namely, an increase in transcription or a decrease in RNA turnover. To determine which of these possibilities was correct, a reporter plasmid (pSB2035) containing the agr P3 promoter fused to the lux-operon (58) was introduced into strains SA564, SA-rpiRc, SA-sarA, and SA-sarA rpiRc. Luciferase activity assays demonstrated that deletion of rpiRc increased transcription of RNAIII from the P3 promoter relative to the wild-type strain, indicating that the augmented RNAIII transcript levels were due to increased transcription rather than reduced RNAIII degradation. Consistent with the quantitative PCR (qPCR) data, the SA-sarA rpiRc double mutant showed markedly reduced luciferase activity, confirming that the presence of sarA is required for high agr promoter activity in an rpiRc mutant background (Fig. 3A). In order to examine if the effect of RpiRc and SarA on the Agr system extends to the P2 promoter driven transcription of RNAII, quantitative PCR (qPCR) on the agrBD genes was performed. Similar to RNAIII transcription and luciferase activity data, the agrBD transcript levels were elevated in the SA-rpiRc mutant compared to the wild-type and the SA-sarA and SA-sarA rpiRc mutant strains (Fig. 3B). In total, these data demonstrate that SarA is required for increased transcription of the agr quorum-sensing system in an S. aureus rpiRc mutant during the exponential growth phase.

FIG 3.

Effect of the deletion of rpiRc and sarA on the agr quorum-sensing system in S. aureus strain SA564. S. aureus strain SA564 or sarA single mutant (■) and their isogenic rpiRc mutants (□) were cultivated for 2 h prior to harvest. (A) Luciferase activities (means ± the SD) of strains harboring the agr P3 promoter reporter plasmid pSB2035 from at least three independent experiments. (B) Total RNA was isolated from bacterial cells and subjected to quantitative real-time RT-PCR, and the relative transcript levels of agrBD were normalized to gyrB and 16S rRNA. Means and SD for at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate are shown.

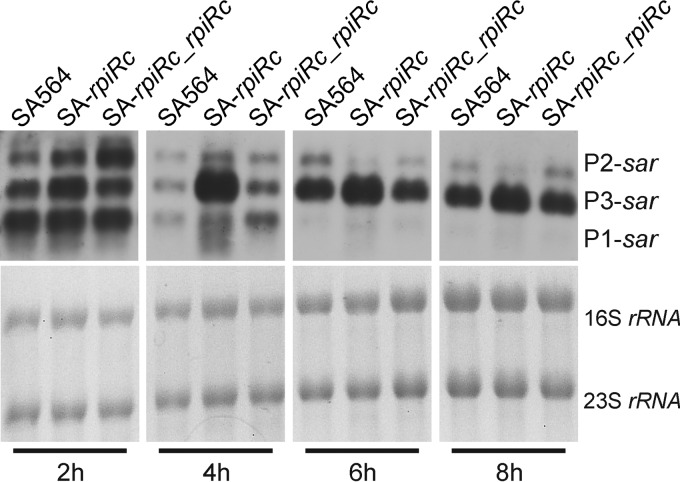

Inactivation of rpiRc increases sarA transcription.

Transcription of RNAIII and virulence determinant synthesis were strongly affected by RpiRc in an agr- and sarA-dependent manner. Based on these data, it was reasonable to hypothesize that RpiRc may exert its regulatory effects by influencing sarA transcription. The sar locus is composed of three overlapping transcripts (termed sarA, sarC, and sarB) that initiate from the promoters P1, P3, and P2, respectively. All three transcripts encompass the major open reading frame, sarA, which codes for the SarA protein (5). Northern blot analysis using a sarA specific probe was performed on total RNA isolated from strains SA564, SA-rpiRc, and the complemented mutant SA-rpiRc_rpiRc (Fig. 4). In the wild-type strain, sarA, sarC, and sarB transcripts were present during the exponential growth phase; however, the intensity of the sarA and sarB transcripts decreased over time. This was consistent with previous observations that sarC transcripts increased during the postexponential growth phase (39, 41). In strain SA-rpiRc the transcription of sarC was markedly increased compared to the wild-type strain SA564. The latter observation was interesting because the sarC transcript initiates from the σB-dependent P3 promoter. Lastly, complementation of the rpiRc mutation restored sar mRNA levels to that of the wild type.

FIG 4.

Positive effect of rpiRc inactivation on transcript levels of sarA. Northern blot analysis of sar transcripts from S. aureus strain SA564, the rpiRc deletion mutant (SA-rpiRc), and the rpiRc mutant carrying the cis-integrated plasmid pEC4-rpiRc for complementation (SA-rpiRc_rpiRc) cultivated for the indicated times was performed. The sar locus originates from three different promoters (P1, P3, and P2) resulting in transcripts that differ in size (0.56, 0.8, and 1.2 kb, respectively). The blot is representative of at least two independent experiments.

Transcription of rpiRc is constant throughout the growth cycle.

Members of the RpiR protein family are metabolite-responsive transcriptional regulators that consist of an N-terminal helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif and a C-terminal sugar isomerase binding domain (63, 64). RpiR regulators can respond to metabolic stimuli and trigger appropriate cellular responses by altering transcription of their respective target genes. In other words, control of RpiR regulatory activity likely occurs at the posttranslational level and is mediated by the concentration of a particular metabolite(s). Although RpiR activity likely occurs posttranslationally, it is possible that additional layers of regulation may occur that increase or decrease the intracellular copy numbers of RpiRc. To determine whether transcription of rpiRc is temporally modulated in S. aureus, qPCR was performed throughout the growth cycle (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In the wild-type strain SA564, mRNA levels of rpiRc remained relatively constant during growth. Additionally, rpiRc mRNA profiles were similar to those of the wild-type strain in the agr, sarA, and sigB mutants. In contrast, the multiple gene regulator A, MgrA, exerted a small positive effect on rpiRc mRNA levels (an ∼2.5-fold difference). Interestingly, inactivation of acnA increased the level of rpiRc mRNA in the exponential growth phase (2.9-fold higher) and yet decreased rpiRc mRNA (2.3-fold lower) in the postexponential growth phase (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In summary, rpiRc mRNA levels are relatively constant during growth and are minimally affected by the most well-studied virulence regulators in S. aureus, indicating that the mode of regulation of RpiRc likely depends on the metabolic state of S. aureus.

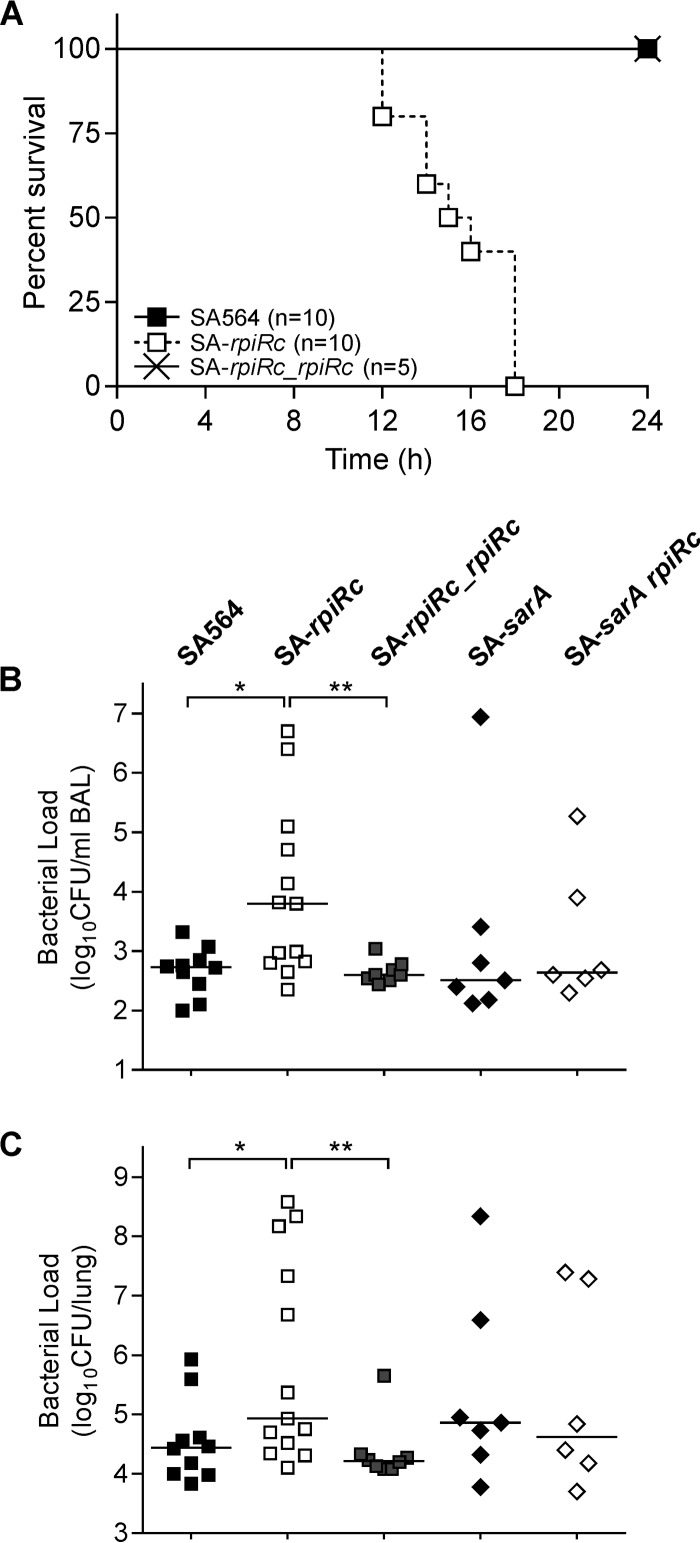

RpiRc attenuates staphylococcal pneumonia and abscess formation.

S. aureus strains lacking rpiRc have major alterations in RNAIII levels that correlated with phenotypic changes of a diverse set of virulence factors (Fig. 1 and 2). These observations suggest that RpiRc may be important in the host-pathogen interaction and affect the pathogenicity of S. aureus. To test this suggestion, the virulence of S. aureus strain SA564, its isogenic rpiRc mutant, and a complemented rpiRc mutant were assessed in a murine model of acute pneumonia (Fig. 5A). C57BL/6N mice were intranasally infected with an inoculation dose of 2.5 × 108 CFU per mouse, and survival was assessed for 24 h. All animals infected with SA-rpiRc succumbed to the infection within 18 h postinoculation, whereas all mice infected with either the wild type or the rpiRc complemented SA-rpiRc mutant were alive after 24 h (Fig. 5A). To determine whether there were differences in the lung bacterial burden, C57BL/6N mice were intranasally infected with a lower infectious dose (108 CFU), the animals were sacrificed after 24 h, the BAL fluids and lung tissues were collected, and viable bacteria enumerated. As expected, the bacterial loads in mice infected with SA-rpiRc were ∼1.3-log higher in both BAL fluid (Fig. 5B) and lung tissue (Fig. 5C) relative to animals infected with strain SA564. The increased bacterial burden of the SA-rpiRc mutant strain in the murine lung is consistent with an increased severity of the infection. Importantly, complementation of the mutant restored wild-type CFU levels, confirming that the observed differences in the mutant were attributable to the absence of rpiRc. Because some of the effects of rpiRc inactivation are dependent upon SarA (Fig. 1, 3, and 4), we sought to determine whether the increased virulence of SA-rpiRc (Fig. 5) was influenced by SarA. To test this hypothesis, mice were infected with the SA-sarA rpiRc double mutant, SA-sarA, or the wild-type strain SA564, and survival was assessed. The bacterial loads of the sarA single and double mutants in lung tissues and BAL samples ranged between both the SA564 wild type and the rpiRc mutant without significant differences, suggesting that SarA is required for the enhanced infectivity of the SA-rpiRc mutant in this model.

FIG 5.

Inactivation of rpiRc results in reduced survival (A) and increased bacterial burden (B and C) of S. aureus in a murine pneumonia model. Wild-type S. aureus strain SA564, the rpiRc deletion mutant (SA-rpiRc), the rpiRc mutant carrying the cis-integrated plasmid pEC4-rpiRc for complementation (SA-rpiRc_rpiRc), and the sarA single (SA-sarA) and rpiRc double (SA-sarA rpiRc) mutants were grown to exponential growth phase (2 h), washed, and intranasally administered to 8- to 9-week-old C57/BL6N mice. (A) The survival of mice using an infectious dose of 2.5 × 108 CFU was monitored. (B and C) After infection with 108 CFU, the bacterial loads in BAL samples (B) and lung tissue homogenates (C) were determined at 24 h postinfection. Each symbol represents an individual animal, and the mean values per group are depicted by horizontal lines. For statistical analysis, nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests were performed (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

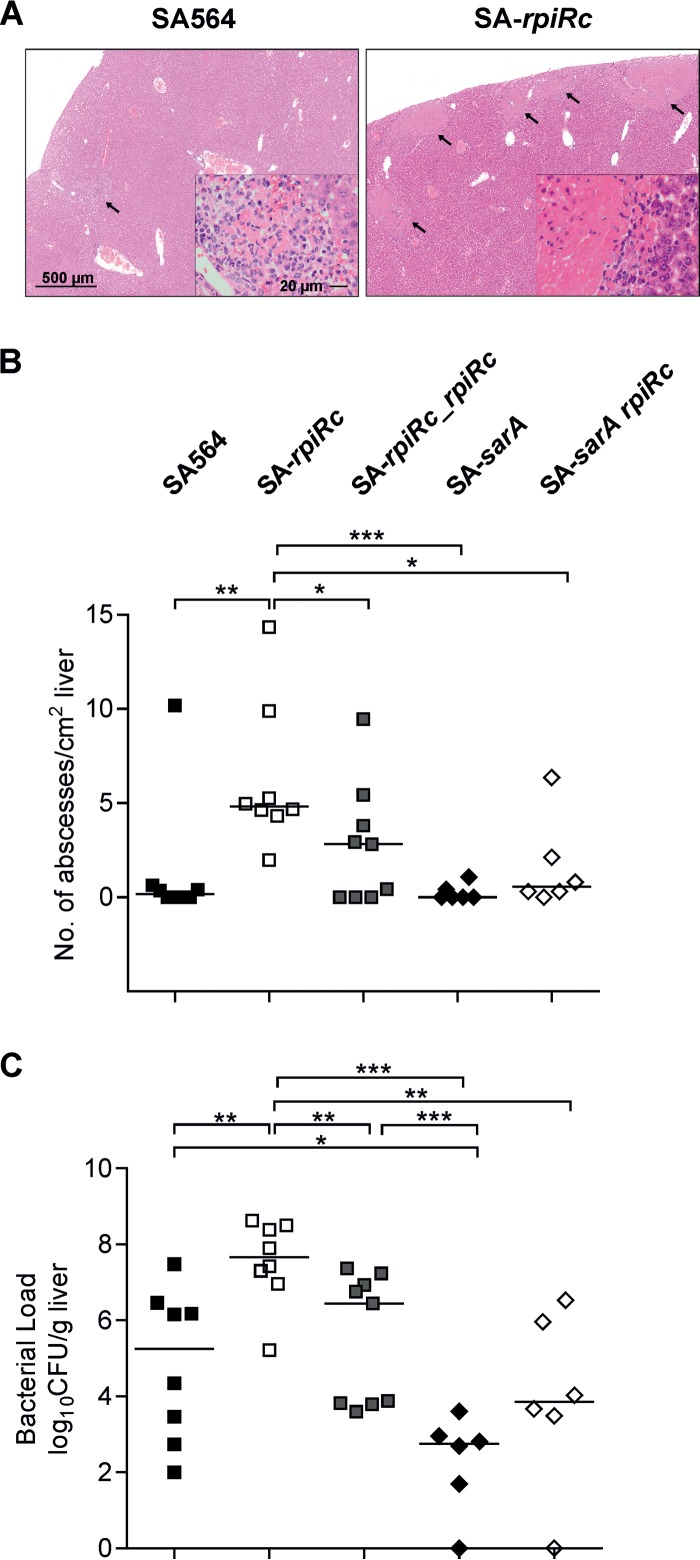

To determine whether this difference in virulence was restricted to the lungs or whether this was a more general phenomenon, a mouse systemic abscess formation model was used to assess the bacterial ability to establish abscesses in the liver and kidneys. In this model, mice were retro-orbitally infected with 107 CFU of S. aureus strain SA564 or its derivatives, and the livers and kidneys were removed at 4 days postinfection for examination of abscess formation and enumeration of the bacterial burden. Histopathology revealed similar abscess lesions within the liver tissue obtained from wild type- and SA-rpiRc-challenged mice (Fig. 6A); however, the number of abscesses (Fig. 6B) and the bacterial burden (Fig. 6C) were significantly elevated in mice infected with strain SA-rpiRc relative to the mouse group challenged with the parental strain SA564. In contrast to the acute pneumonia model, inactivation of sarA resulted in significant reductions in the bacterial burden and abscesses in liver tissue compared to SA564, SA-rpiRc, and SA-rpiRc_rpiRc (Fig. 6). The bacterial burden in organs from mice infected with the SA-sarA rpiRc double mutant was significantly reduced compared to that seen with SA-rpiRc-infected mice and similar to that seen with SA-sarA-infected mice, confirming the prominent role of SarA in murine infection (20–22). Similarly, bacterial burdens were increased in the kidneys of mice infected with strain SA-rpiRc relative to the isogenic parental strain SA564 (data not shown). Taken together, the RpiRc regulator serves as an important negative modulator of pathogenicity in S. aureus in two different murine infection models, and this was partially dependent on SarA.

FIG 6.

Inactivation of rpiRc results in more abscesses (A and B) and higher bacterial burdens (C) in a murine abscess formation model. S. aureus wild-type strain SA564, the rpiRc deletion mutant (SA-rpiRc), the rpiRc mutant carrying the cis-integrated complementation plasmid pEC4-rpiRc (SA-rpiRc_rpiRc), and the sarA single (SA-sarA) and rpiRc double (SA-sarA rpiRc) mutants were grown to exponential growth phase (2 h) and washed, and 107 CFU were administered via retroorbital injection to C57BL/6N mice. At 4 days postinfection, the mice were euthanized, and the livers were removed. Representative H&E staining of liver sections from the wild type and the rpiRc mutant showing abscess lesions (arrows) is shown. In panel A, the magnification bar represents 500 μm (20 μm in each inset). (B) The number of abscesses was enumerated and normalized to the observed tissue area. (C) Bacterial loads in homogenized liver. Each symbol represents an individual animal, and the mean values per group are depicted by horizontal lines. For statistical analysis, nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests were performed (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

During aerobic planktonic growth, S. aureus genes encoding cell surface proteins are upregulated in the exponential growth phase and downregulated in the postexponential growth phase, whereas genes encoding secreted toxins and capsule are upregulated in the postexponential growth phase (4, 31). This growth-phase-dependent switch between cell-associated proteins and secreted proteins coincides with derepression of the TCA cycle (43, 44, 65) and activation of the Agr quorum-sensing system (4). Inactivation of rpiRc greatly increased the transcription of RNAIII (Fig. 1A and Fig. 3A), suggesting that RpiRc can function as a metabolite-responsive modulator of the agr quorum-sensing system. Not only did rpiRc inactivation increase RNAIII transcription, but it also increased RNAII synthesis (Fig. 3B), which suggests that RpiRc suppresses quorum-sensing. This suppression of quorum sensing is likely indirect, requiring the action of SarA in the exponential growth phase. In contrast, transcriptional regulation of hla was more complicated. Deletion of rpiRc and sigB, also a negative effector of alpha-toxin (36, 38, 40), resulted in a synergistic increase in hla mRNA and increased hemolysis of erythrocytes, suggesting a regulatory linkage between RpiRc and σB. Interestingly, inactivation of sarA increased hla mRNA levels and hemolytic activity relative to the wild-type strain SA564; however, a rpiRc sarA double mutant had an only slightly increased hla mRNA level but similar hemolytic activity to the wild-type strain. This could be due to SarA having both an activating (66–68) and a repressing (69–71) influence on hla transcription, depending on the regulatory configuration of the strain genetic background (i.e., the presence of σB or SarS [61, 69]).

In contrast to secreted toxins, the synthesis of cell surface-associated proteins (e.g., protein A) is greatest at low cell densities and is repressed by RNAIII (4). Specifically, RNAIII negatively affects protein A at the posttranscriptional level by binding spa mRNA and facilitating RNase III-mediated degradation (72, 73). As with our previous observations (3), protein A accumulation was nearly abolished in the rpiRc mutant throughout growth. As expected, acnA and mgrA inactivation increased spa mRNA levels relative to the wild-type strain (26, 29); however, spa mRNA levels were markedly reduced in the acnA and mgrA mutant strains when rpiRc was deleted. This is interesting because both MgrA and TCA cycle activity suppress spa transcription, suggesting that both MgrA and TCA cycle activity have lesser roles in influencing spa transcription than does RpiRc. Conversely, the SA-sarA rpiRc double mutant maintained elevated spa levels, signifying that RpiRc is dependent on the presence of SarA to exert its role on protein A synthesis. Lastly, the transcription and synthesis of protein A required σB and inactivation of rpiRc could not overcome the absence of σB. Taken together, it seems likely the decrease in protein A synthesis in strain SA-rpiRc is due to an increase in σB-dependent transcription of the sar locus (Fig. 4).

Capsule protects S. aureus and enhances virulence by impeding C3 complement binding and phagocytosis (74). Typically, capsule is synthesized in the postexponential growth phase, and this requires TCA cycle activity (62). As expected, capA mRNA, which encodes the first enzyme for capsule biosynthesis, increased over time in wild-type strain SA564. Interestingly, inactivation of acnA resulted in very high capA mRNA levels throughout the growth cycle (Fig. 1D) (36). In addition, inactivation of the TCA cycle did not decrease capsule accumulation but actually increased it. This contrast between the present study and our previous work is likely due to differences in cultivation times; specifically, in the previous study, overnight cultures were used for capsule analyses, whereas in the present study bacteria were harvested after 4 h of incubation when preferred carbon sources are still available. Consistent with this suggestion, after 18 h of cultivation, capsule accumulation was nominal in the acnA mutant (data not shown). Similar to acnA inactivation, mutation of rpiRc greatly increased capA mRNA levels, and this effect was synergistic in the SA-acnA rpiRc double mutant. Interestingly, capsule accumulation was still elevated in strain SA-acnA rpiRc after 18 h of growth (data not shown), indicating that metabolic alterations due to disruption of rpiRc can overcome the TCA cycle-dependent requirements for capsule biosynthesis. Despite no major differences in capA mRNA levels between single and double mutants of mgrA or sarA and rpiRc, the accumulation of capsule was strongly enhanced in the presence of an rpiRc mutation, further suggesting that RpiRc exerts some of its effects independent of transcriptional regulation. In contrast, the negative effect of sigB inactivation (36, 75) abolished the transcription and synthesis of capsule in S. aureus, irrespective of the presence of RpiRc. Taken together, RpiRc-dependent effects on RNAIII and virulence determinants are linked to σB, SarA, and the bacterial metabolic status.

Inactivation of rpiRc strongly altered virulence determinant regulation; hence, it was reasonable to hypothesize that RpiRc alters the host-pathogen interaction and disease progression. To assess the effect of rpiRc inactivation on S. aureus virulence, two murine infection models were used: a pulmonary infection model and a systemic abscess model. These models were chosen because they mimic S. aureus infections that are frequently associated with difficult to treat complications in humans (76–79) and because RNAIII-regulated virulence determinants are known to be important in both models (77, 80–82). For example, the RNAIII-regulated alpha-hemolysin is important for respiratory disease progression by functioning as a cytotoxic factor that promotes pore formation and facilitates S. aureus entry into the peripheral blood system (59, 83, 84). In the murine model of pneumonia, 100% of the mice infected with strain SA-rpiRc succumbed to the infection within 24 h, whereas all mice infected with the wild-type strain survived, demonstrating the importance of RpiRc in the infection process. This is consistent with higher bacterial loads in the BAL samples and lung homogenates of mice infected with the rpiRc mutant strain than in those of mice infected with the wild-type strain SA564. In the murine abscess model, systemically applied S. aureus can disseminate within the host and form abscesses at almost any anatomical site (77). In this infection model, alpha-hemolysin (77), protein A (80), and capsule (85, 86) are important bacterial determinants of abscess formation. Similar to the pneumonia model, inactivation of rpiRc increased the bacterial burden and the number of abscesses in visceral organs, demonstrating that the importance of RpiRc to pathogenicity is independent of the animal model. The in vitro importance of SarA in mediating some aspects of RpiRc regulation of virulence determinants led us to examine whether SarA mediates the in vivo effects of rpiRc inactivation using both infection models. The virulence levels of strains SA-rpiRc and SA-rpiRc sarA were similar (Fig. 5 and 6), suggesting that the presence of SarA is required for RpiRc to exert its full function as an attenuator of virulence. The metabolite-responsive regulators CodY (87) and CcpE (51, 88) have similar negative effects on pathogenicity. In contrast, inactivation of ccpA decreased the bacterial load in a murine infection model (47). This is likely due to CcpA affecting transcription of virulence genes in S. aureus, in particular the exotoxin alpha-toxin gene (48).

Conclusion.

The RpiR family of metabolite-responsive regulators functions to link central metabolism to virulence determinant biosynthesis in S. aureus (3). This linkage is critical because it connects the availability of the central metabolism generated biosynthetic intermediates (e.g., α-ketoglutarate and glucose-6-phosphate) with the synthesis of virulence determinants. Without biosynthetic intermediates, synthesis of biosynthetic precursors (e.g., amino acids and amino sugars) will be impaired, which will prevent the polymerizing and assembly reactions from producing virulence determinants and other cellular components. In the present study, we determined that the agr and sar loci and σB function with RpiRc to modulate transcription and synthesis of several critical S. aureus virulence determinants. The significance of RpiRc was demonstrated in an acute pneumonia model and a systemic abscess formation model, where inactivation of rpiRc markedly increased mortality and the bacterial burden in mice. These data demonstrate that RpiRc functions to repress virulence determinant biosynthesis, which attenuates virulence in this clinically important pathogen. The effects of RpiRc are likely mediated through its ability to bind metabolites; however, this requires additional testing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported, in whole or in part, by grant T6031900 from the University of Saarland to R.G., grant BI 1350/1-2 to M.B., and Transregio 34 (TR34) to C.W. from the German Research Foundation. C.Y.L. was supported by grant AI113766 from the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. G.A.S. was supported by funds provided through the Hatch Act to the University of Nebraska Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources and by funds provided through the National Institutes of Health (AI087668).

We declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00285-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lowy FD. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somerville GA, Proctor RA. 2009. At the crossroads of bacterial metabolism and virulence factor synthesis in staphylococci. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:233–248. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00005-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Y, Nandakumar R, Sadykov MR, Madayiputhiya N, Luong TT, Gaupp R, Lee CY, Somerville GA. 2011. RpiR homologues may link Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII synthesis and pentose phosphate pathway regulation. J Bacteriol 193:6187–6196. doi: 10.1128/JB.05930-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novick RP, Geisinger E. 2008. Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu Rev Genet 42:541–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer MG, Heinrichs JH, Cheung AL. 1996. The molecular architecture of the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 178:4563–4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison JM, Anderson KL, Beenken KE, Smeltzer MS, Dunman PM. 2012. The staphylococcal accessory regulator, SarA, is an RNA-binding protein that modulates the mRNA turnover properties of late-exponential and stationary-phase Staphylococcus aureus cells. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:26. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blevins JS, Gillaspy AF, Rechtin TM, Hurlburt BK, Smeltzer MS. 1999. The staphylococcal accessory regulator (sar) represses transcription of the Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin gene (cna) in an agr-independent manner. Mol Microbiol 33:317–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunman PM, Murphy E, Haney S, Palacios D, Tucker-Kellogg G, Wu S, Brown EL, Zagursky RJ, Shlaes D, Projan SJ. 2001. Transcription profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J Bacteriol 183:7341–7353. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7341-7353.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolz C, Pöhlmann-Dietze P, Steinhuber A, Chien YT, Manna A, van Wamel W, Cheung A. 2000. agr-independent regulation of fibronectin-binding protein(s) by the regulatory locus sar in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 36:230–243. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyes D, Andrey DO, Monod A, Kelley WL, Zhang G, Cheung AL. 2011. Coordinated regulation by AgrA, SarA, and SarR to control agr expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 193:6020–6031. doi: 10.1128/JB.05436-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien Y, Manna AC, Projan SJ, Cheung AL. 1999. SarA, a global regulator of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus, binds to a conserved motif essential for sar-dependent gene regulation. J Biol Chem 274:37169–37176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimoto DF, Brunskill EW, Bayles KW. 2000. Analysis of genetic elements controlling Staphylococcus aureus lrgAB expression: potential role of DNA topology in SarA regulation. J Bacteriol 182:4822–4828. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.17.4822-4828.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Manna AC, Pan CH, Kriksunov IA, Thiel DJ, Cheung AL, Zhang G. 2006. Structural and function analyses of the global regulatory protein SarA from Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:2392–2397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510439103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts C, Anderson KL, Murphy E, Projan SJ, Mounts W, Hurlburt B, Smeltzer M, Overbeek R, Disz T, Dunman PM. 2006. Characterizing the effect of the Staphylococcus aureus virulence factor regulator, SarA, on log-phase mRNA half-lives. J Bacteriol 188:2593–2603. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2593-2603.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterba KM, Mackintosh SG, Blevins JS, Hurlburt BK, Smeltzer MS. 2003. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus SarA binding sites. J Bacteriol 185:4410–4417. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4410-4417.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdelnour A, Arvidson S, Bremell T, Ryden C, Tarkowski A. 1993. The accessory gene regulator (agr) controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in a murine arthritis model. Infect Immun 61:3879–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung AL, Eberhardt KJ, Chung E, Yeaman MR, Sullam PM, Ramos M, Bayer AS. 1994. Diminished virulence of a sar-/agr- mutant of Staphylococcus aureus in the rabbit model of endocarditis. J Clin Invest 94:1815–1822. doi: 10.1172/JCI117530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillaspy AF, Hickmon SG, Skinner RA, Thomas JR, Nelson CL, Smeltzer MS. 1995. Role of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in pathogenesis of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. Infect Immun 63:3373–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Wamel W, Xiong YQ, Bayer AS, Yeaman MR, Nast CC, Cheung AL. 2002. Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus type 5 capsular polysaccharides by agr and sarA in vitro and in an experimental endocarditis model. Microb Pathog 33:73–79. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2002.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blevins JS, Elasri MO, Allmendinger SD, Beenken KE, Skinner RA, Thomas JR, Smeltzer MS. 2003. Role of sarA in the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal infection. Infect Immun 71:516–523. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.516-523.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung AL, Yeaman MR, Sullam PM, Witt MD, Bayer AS. 1994. Role of the sar locus of Staphylococcus aureus in induction of endocarditis in rabbits. Infect Immun 62:1719–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsson IM, Bremell T, Ryden C, Cheung AL, Tarkowski A. 1996. Role of the staphylococcal accessory gene regulator (sar) in septic arthritis. Infect Immun 64:4438–4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luong TT, Dunman PM, Murphy E, Projan SJ, Lee CY. 2006. Transcription profiling of the mgrA regulon in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 188:1899–1910. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1899-1910.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingavale SS, Van Wamel W, Cheung AL. 2003. Characterization of RAT, an autolysis regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 48:1451–1466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Truong-Bolduc QC, Zhang X, Hooper DC. 2003. Characterization of NorR protein, a multifunctional regulator of norA expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 185:3127–3138. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.10.3127-3138.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luong TT, Newell SW, Lee CY. 2003. Mgr, a novel global regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 185:3703–3710. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.13.3703-3710.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen PR, Bae T, Williams WA, Duguid EM, Rice PA, Schneewind O, He C. 2006. An oxidation-sensing mechanism is used by the global regulator MgrA in Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Chem Biol 2:591–595. doi: 10.1038/nchembio820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonsson IM, Lindholm C, Luong TT, Lee CY, Tarkowski A. 2008. mgrA regulates staphylococcal virulence important for induction and progression of septic arthritis and sepsis. Microbes Infect 10:1229–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingavale S, van Wamel W, Luong TT, Lee CY, Cheung AL. 2005. Rat/MgrA, a regulator of autolysis, is a regulator of virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 73:1423–1431. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1423-1431.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Truong-Bolduc QC, Ding Y, Hooper DC. 2008. Posttranslational modification influences the effects of MgrA on norA expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 190:7375–7381. doi: 10.1128/JB.01068-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung AL, Bayer AS, Zhang G, Gresham H, Xiong Y-Q. 2004. Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 40:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen HY, Chen CC, Fang CS, Hsieh YT, Lin MH, Shu JC. 2011. Vancomycin activates σB in vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resulting in the enhancement of cytotoxicity. PLoS One 6:e24472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hecker M, Reder A, Fuchs S, Pagels M, Engelmann S. 2009. Physiological proteomics and stress/starvation responses in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. Res Microbiol 160:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kullik I, Giachino P, Fuchs T. 1998. Deletion of the alternative sigma factor σB in Staphylococcus aureus reveals its function as a global regulator of virulence genes. J Bacteriol 180:4814–4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kullik II, Giachino P. 1997. The alternative sigma factor σB in Staphylococcus aureus: regulation of the sigB operon in response to growth phase and heat shock. Arch Microbiol 167:151–159. doi: 10.1007/s002030050428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bischoff M, Dunman P, Kormanec J, Macapagal D, Murphy E, Mounts W, Berger-Bachi B, Projan S. 2004. Microarray-based analysis of the Staphylococcus aureus σB regulon. J Bacteriol 186:4085–4099. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4085-4099.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bischoff M, Entenza JM, Giachino P. 2001. Influence of a functional sigB operon on the global regulators sar and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 183:5171–5179. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.17.5171-5179.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheung AL, Chien YT, Bayer AS. 1999. Hyperproduction of alpha-hemolysin in a sigB mutant is associated with elevated SarA expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 67:1331–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deora R, Tseng T, Misra TK. 1997. Alternative transcription factor σSB of Staphylococcus aureus: characterization and role in transcription of the global regulatory locus sar. J Bacteriol 179:6355–6359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horsburgh MJ, Aish JL, White IJ, Shaw L, Lithgow JK, Foster SJ. 2002. sigmaB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J Bacteriol 184:5457–5467. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5457-5467.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manna AC, Bayer MG, Cheung AL. 1998. Transcriptional analysis of different promoters in the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 180:3828–3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chatterjee I, Herrmann M, Proctor RA, Peters G, Kahl BC. 2007. Enhanced post-stationary-phase survival of a clinical thymidine-dependent small-colony variant of Staphylococcus aureus results from lack of a functional tricarboxylic acid cycle. J Bacteriol 189:2936–2940. doi: 10.1128/JB.01444-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaupp R, Schlag S, Liebeke M, Lalk M, Gotz F. 2010. Advantage of upregulation of succinate dehydrogenase in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J Bacteriol 192:2385–2394. doi: 10.1128/JB.01472-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Somerville GA, Chaussee MS, Morgan CI, Fitzgerald JR, Dorward DW, Reitzer LJ, Musser JM. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus aconitase inactivation unexpectedly inhibits post-exponential-phase growth and enhances stationary-phase survival. Infect Immun 70:6373–6382. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6373-6382.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Somerville GA, Cockayne A, Dürr M, Peschel A, Otto M, Musser JM. 2003. Synthesis and deformylation of Staphylococcus aureus delta-toxin are linked to tricarboxylic acid cycle activity. J Bacteriol 185:6686–6694. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.22.6686-6694.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu Y, Xiong YQ, Sadykov MR, Fey PD, Lei MG, Lee CY, Bayer AS, Somerville GA. 2009. Tricarboxylic acid cycle-dependent attenuation of Staphylococcus aureus in vivo virulence by selective inhibition of amino acid transport. Infect Immun 77:4256–4264. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00195-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li C, Sun F, Cho H, Yelavarthi V, Sohn C, He C, Schneewind O, Bae T. 2010. CcpA mediates proline auxotrophy and is required for Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. J Bacteriol 192:3883–3892. doi: 10.1128/JB.00237-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seidl K, Stucki M, Ruegg M, Goerke C, Wolz C, Harris L, Berger-Bächi B, Bischoff M. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus CcpA affects virulence determinant production and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1183–1194. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1183-1194.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Majerczyk CD, Dunman PM, Luong TT, Lee CY, Sadykov MR, Somerville GA, Bodi K, Sonenshein AL. 2010. Direct targets of CodY in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 192:2861–2877. doi: 10.1128/JB.00220-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pohl K, Francois P, Stenz L, Schlink F, Geiger T, Herbert S, Goerke C, Schrenzel J, Wolz C. 2009. CodY in Staphylococcus aureus: a regulatory link between metabolism and virulence gene expression. J Bacteriol 191:2953–2963. doi: 10.1128/JB.01492-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartmann T, Baronian G, Nippe N, Voss M, Schulthess B, Wolz C, Eisenbeis J, Schmidt-Hohagen K, Gaupp R, Sunderkotter C, Beisswenger C, Bals R, Somerville GA, Herrmann M, Molle V, Bischoff M. 2014. The catabolite control protein E (CcpE) affects virulence determinant production and pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 289:29701–29711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.584979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hartmann T, Zhang B, Baronian G, Schulthess B, Homerova D, Grubmuller S, Kutzner E, Gaupp R, Bertram R, Powers R, Eisenreich W, Kormanec J, Herrmann M, Molle V, Somerville GA, Bischoff M. 2013. Catabolite control protein E (CcpE) is a LysR-type transcriptional regulator of TCA cycle activity in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 288:36116–36128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.516302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pagels M, Fuchs S, Pané-Farré J, Kohler C, Menschner L, Hecker M, McNamarra PJ, Bauer MC, von Wachenfeldt C, Liebeke M, Lalk M, Sander G, von Eiff C, Proctor RA, Engelmann S. 2010. Redox sensing by a Rex-family repressor is involved in the regulation of anaerobic gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 76:1142–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deutscher J, Kuster E, Bergstedt U, Charrier V, Hillen W. 1995. Protein kinase-dependent HPr/CcpA interaction links glycolytic activity to carbon catabolite repression in gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol 15:1049–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Majerczyk CD, Sadykov MR, Luong TT, Lee C, Somerville GA, Sonenshein AL. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus CodY negatively regulates virulence gene expression. J Bacteriol 190:2257–2265. doi: 10.1128/JB.01545-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goerke C, Campana S, Bayer MG, Döring G, Botzenhart K, Wolz C. 2000. Direct quantitative transcript analysis of the agr regulon of Staphylococcus aureus during human infection in comparison to the expression profile in vitro. Infect Immun 68:1304–1311. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.3.1304-1311.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luong TT, Sau K, Roux C, Sau S, Dunman PM, Lee CY. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus ClpC divergently regulates capsule via sae and codY in strain Newman but activates capsule via codY in strain UAMS-1 and in strain Newman with repaired saeS. J Bacteriol 193:686–694. doi: 10.1128/JB.00987-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qazi SN, Counil E, Morrissey J, Rees CE, Cockayne A, Winzer K, Chan WC, Williams P, Hill PJ. 2001. agr expression precedes escape of internalized Staphylococcus aureus from the host endosome. Infect Immun 69:7074–7082. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.7074-7082.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bubeck Wardenburg J, Patel RJ, Schneewind O. 2007. Surface proteins and exotoxins are required for the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Infect Immun 75:1040–1044. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01313-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wonnenberg B, Tschernig T, Voss M, Bischoff M, Meier C, Schirmer SH, Langer F, Bals R, Beisswenger C. 2014. Probenecid reduces infection and inflammation in acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Int J Med Microbiol 304:725–729. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oscarsson J, Kanth A, Tegmark-Wisell K, Arvidson S. 2006. SarA is a repressor of hla (alpha-hemolysin) transcription in Staphylococcus aureus: its apparent role as an activator of hla in the prototype strain NCTC 8325 depends on reduced expression of sarS. J Bacteriol 188:8526–8533. doi: 10.1128/JB.00866-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sadykov MR, Mattes TA, Luong TT, Zhu Y, Day SR, Sifri CD, Lee CY, Somerville GA. 2010. Tricarboxylic acid cycle-dependent synthesis of Staphylococcus aureus type 5 and 8 capsular polysaccharides. J Bacteriol 192:1459–1462. doi: 10.1128/JB.01377-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bateman A. 1999. The SIS domain: a phosphosugar-binding domain. Trends Biochem Sci 24:94–95. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sorensen KI, Hove-Jensen B. 1996. Ribose catabolism of Escherichia coli: characterization of the rpiB gene encoding ribose phosphate isomerase B and of the rpiR gene, which is involved in regulation of rpiB expression. J Bacteriol 178:1003–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Somerville GA, Said-Salim B, Wickman JM, Raffel SJ, Kreiswirth BN, Musser JM. 2003. Correlation of acetate catabolism and growth yield in Staphylococcus aureus: implications for host-pathogen interactions. Infect Immun 71:4724–4732. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4724-4732.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chan PF, Foster SJ. 1998. Role of SarA in virulence determinant production and environmental signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 180:6232–6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheung AL, Ying P. 1994. Regulation of alpha- and beta-hemolysins by the sar locus of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 176:580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tegmark K, Karlsson A, Arvidson S. 2000. Identification and characterization of SarH1, a new global regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 37:398–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blevins JS, Beenken KE, Elasri MO, Hurlburt BK, Smeltzer MS. 2002. Strain-dependent differences in the regulatory roles of sarA and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 70:470–480. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.470-480.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheung AL, Koomey JM, Butler CA, Projan SJ, Fischetti VA. 1992. Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus (sar) distinct from agr. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:6462–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Karlsson A, Arvidson S. 2002. Variation in extracellular protease production among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus due to different levels of expression of the protease repressor sarA. Infect Immun 70:4239–4246. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4239-4246.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benito Y, Kolb FA, Romby P, Lina G, Etienne J, Vandenesch F. 2000. Probing the structure of RNAIII, the Staphylococcus aureus agr regulatory RNA, and identification of the RNA domain involved in repression of protein A expression. RNA 6:668–679. doi: 10.1017/S1355838200992550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huntzinger E, Boisset S, Saveanu C, Benito Y, Geissmann T, Namane A, Lina G, Etienne J, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C, Jacquier A, Vandenesch F, Romby P. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII and the endoribonuclease III coordinately regulate spa gene expression. EMBO J 24:824–835. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.O'Riordan K, Lee JC. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides. Clin Microbiol Rev 17:218–234. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.218-234.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meier S, Goerke C, Wolz C, Seidl K, Homerova D, Schulthess B, Kormanec J, Berger-Bachi B, Bischoff M. 2007. σB and the σB-dependent arlRS and yabJ-spoVG loci affect capsule formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 75:4562–4571. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00392-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheng AG, DeDent AC, Schneewind O, Missiakas D. 2011. A play in four acts: Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation. Trends Microbiol 19:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kobayashi SD, Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. 2015. Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus abscesses. Am J Pathol 185:1518–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Parker D, Prince A. 2012. Immunopathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pulmonary infection. Semin Immunopathol 34:281–297. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. 2000. Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 21:510–515. doi: 10.1086/501795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheng AG, Kim HK, Burts ML, Krausz T, Schneewind O, Missiakas DM. 2009. Genetic requirements for Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation and persistence in host tissues. FASEB J 23:3393–3404. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-135467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gomez MI, Lee A, Reddy B, Muir A, Soong G, Pitt A, Cheung A, Prince A. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus protein A induces airway epithelial inflammatory responses by activating TNFR1. Nat Med 10:842–848. doi: 10.1038/nm1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heyer G, Saba S, Adamo R, Rush W, Soong G, Cheung A, Prince A. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus agr and sarA functions are required for invasive infection but not inflammatory responses in the lung. Infect Immun 70:127–133. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.127-133.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bartlett AH, Foster TJ, Hayashida A, Park PW. 2008. Alpha-toxin facilitates the generation of CXC chemokine gradients and stimulates neutrophil homing in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. J Infect Dis 198:1529–1535. doi: 10.1086/592758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McElroy MC, Harty HR, Hosford GE, Boylan GM, Pittet JF, Foster TJ. 1999. Alpha-toxin damages the air-blood barrier of the lung in a rat model of Staphylococcus aureus-induced pneumonia. Infect Immun 67:5541–5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tzianabos AO, Wang JY, Lee JC. 2001. Structural rationale for the modulation of abscess formation by Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:9365–9370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161175598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Watts A, Ke D, Wang Q, Pillay A, Nicholson-Weller A, Lee JC. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus strains that express serotype 5 or serotype 8 capsular polysaccharides differ in virulence. Infect Immun 73:3502–3511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3502-3511.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Montgomery CP, Boyle-Vavra S, Roux A, Ebine K, Sonenshein AL, Daum RS. 2012. CodY deletion enhances in vivo virulence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone USA300. Infect Immun 80:2382–2389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06172-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ding Y, Liu X, Chen F, Di H, Xu B, Zhou L, Deng X, Wu M, Yang CG, Lan L. 2014. Metabolic sensor governing bacterial virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E4981–E4990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411077111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Somerville GA, Beres SB, Fitzgerald JR, DeLeo FR, Cole RL, Hoff JS, Musser JM. 2002. In vitro serial passage of Staphylococcus aureus: changes in physiology, virulence factor production, and agr nucleotide sequence. J Bacteriol 184:1430–1437. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1430-1437.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brückner R. 1997. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 151:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00116-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.