Abstract

In humans, cultural traditions often change in ways which increase efficiency and functionality. This process, widely referred to as cumulative cultural evolution, sees beneficial traits preferentially retained, and it is so pervasive that we may be inclined to take it for granted. However, directional change of this kind appears to distinguish human cultural traditions from behavioural traditions that have been documented in other animals. Cumulative culture is therefore attracting an increasing amount of attention within psychology, and researchers have begun to develop methods of studying this phenomenon under controlled conditions. These studies have now addressed a number of different questions, including which learning mechanisms may be implicated, and how the resulting behaviours may be influenced by factors such as population structure. The current article provides a synopsis of some of these studies, and highlights some of the unresolved issues in this field.

Keywords: cumulative culture, cultural evolution, imitation, microsocieties, ratchet effect

Cumulative cultural evolution is a process by which a series of social transmission events results in successive improvements in performance, arising due to an accumulation of modifications to the transmitted behaviours. The human capacity for cumulative culture therefore allows us to capitalise on the accumulated knowledge and experience of previous generations, such that we routinely make use of inventions and discoveries which would be unlikely or impossible for us to have achieved by ourselves (e.g. every time we make a phone call, or heat food in a microwave oven). Furthermore, techniques and technologies are often developed further based on existing knowledge, and such accomplishments are within reach of any typical individual. In this respect, human culture has been very aptly described by Tomasello (e.g. Tomasello, Kruger & Ratner, 1993) as exhibiting a “ratchet effect”: beneficial modifications and improvements tend to be preserved such that skills and technology increase in efficiency and functionality over successive generations, with little backwards slippage.

The phenomenon of cumulative culture is so ubiquitous within human societies that we may be tempted to dismiss this capacity as relatively unremarkable. Similarly, it is easy to underappreciate the significance of its impact on human behaviour, for the simple reason that it is difficult to imagine any human society without it. However, a comparative perspective readily prompts a very different view, which makes it is quite apparent that the capacity for cumulative culture is neither trivial nor inconsequential. Despite the universality of cumulative culture across human societies, there is currently little evidence of it in any nonhuman species (Dean, Vale, Laland, Flynn & Kendal, 2014). Although social learning has been identified in many animals (broadly defined as learning that is facilitated by contact with experienced individuals, or the physical traces left by experienced individuals, c.f. Heyes, 1994), evidence of anything akin to the ratchet effect remains elusive. Even the most complex socially learned behaviours of nonhuman primates are generally acknowledged to be no more complex than the trial-and-error achievements of some individuals (Tennie, Call & Tomasello, 2009). This evolutionary anomaly therefore presents something of a puzzle. The capacity for cumulative culture has allowed modern humans to dominate the planet (Boyd, Richerson & Henrich, 2011), so it may represent a uniquely powerful mechanism for adapting to novel and changing environments. Its apparent absence in other species therefore merits serious consideration.

Appreciation of the significance of cumulative culture prompts a number of fairly fundamental questions for behavioural scientists. One such question concerns the cognitive capacities that are required to generate this process, the answer to which may help us to understand why we do not see it in other species. Related to this, and making a reasonable assumption of evolutionary continuity, it is also of interest to determine the extent to which similar processes may be present in other species, particularly those closely related to us. In addition, given that many examples of complex human behaviour are likely to be consequences of cumulative cultural evolution, this prompts the question of whether this process places its own constraints on the behaviours that are likely to emerge. Does repeated social transmission create unique pressures not present in individual trial-and-error learning or genetic evolution, such that behaviours tend to be shaped and filtered in particular (and possibly predictable) ways? Extending this logic, can the form (or indeed presence or absence) of certain behaviours within specific populations potentially be explained as a consequence of peculiarities of the transmission process within that population? These questions touch on fundamental issues within psychology, such as understanding cross-cultural similarities and differences, and tracing the evolutionary origins of complex human cognition.

Laboratory Studies of Cumulative Culture

Despite the significant theoretical implications of the questions detailed above, finding ways to investigate them is not necessarily straightforward. Cumulative cultural evolution describes a property of behaviour at the level of the group, rather than the individual, and therefore (in contrast to traditional psychological methods) multiple individuals are required for a single experimental replicate. It also describes a dynamic process, rather than a static phenomenon, characterised by directional behavioural change over time. If we aspire to address some of these questions then we need to be able to demonstrate this process in action, under conditions that allow us to manipulate variables of interest (Caldwell & Millen, 2008a).

Motivated by this goal, Caldwell & Millen (2008b) set out simply to establish that it was possible to study this process under controlled conditions. In order to demonstrate a social learning ratchet effect it must be possible to show, at a minimum, that learning from an individual who has themselves had the benefit of social information must be typically more valuable than learning from an individual who has had no such opportunity. Therefore we aimed to devise tasks in which successive attempts, carried out by different individuals, could potentially result in improved performance. The tasks also required objective measures of success, and had to be achievable within experimentally-feasible periods of time.

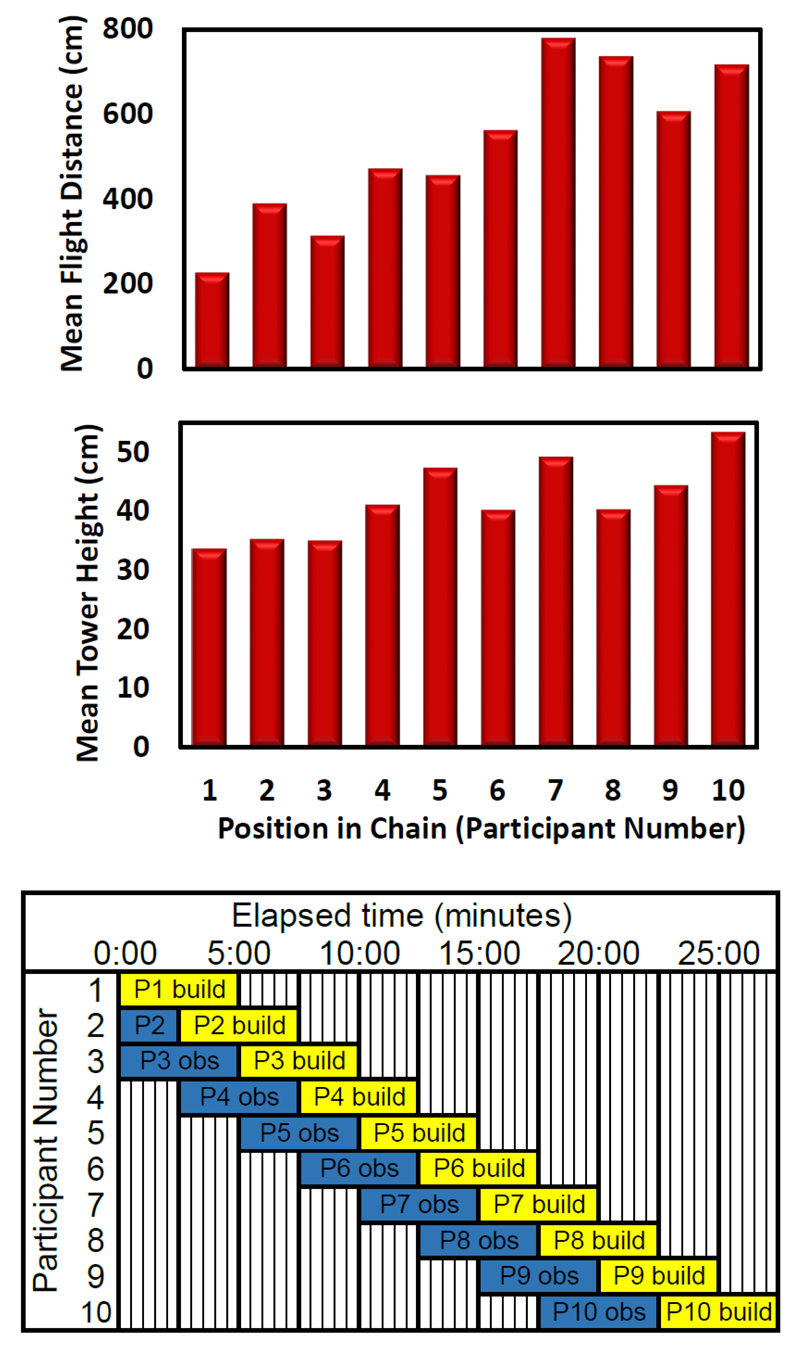

Our initial experiments (reported in full in Caldwell & Millen, 2008b) used two different tasks. In one, participants were asked to build a paper aeroplane from a single sheet of paper, with success measured by the flight distance of their plane. In the other, participants were asked to build a tower from raw spaghetti and a small amount of modelling clay, with success measured by the height of their tower. For each task, we ran ten chains each composed of ten participants, who took part in the task one after the other, with opportunities to observe individuals who took part immediately before themselves. Figure 1 displays a schematic illustrating the role of each of the ten participants in any given chain at any point during testing. The purpose of structuring the participants’ activity in this way was to create a simulated, scaled-down population of learners who came into contact with members of adjacent generations with overlapping experimental lifespans. Such research designs are sometimes referred to as “microsocieties” (Baum, Richerson, Efferson & Paciotti, 2004) or “microcultures” (Jacobs & Campbell, 1961). Further experiments using similar approaches to studying cumulative culture are reviewed in Whiten, Caldwell & Mesoudi (2016).

Figure 1.

Participants’ scores on goal measures increased over generations of the microsocieties. Top panel displays flight distances of paper aeroplanes, and centre panel displays heights of towers, each based on the mean performance across ten microsocieties, as detailed in Caldwell & Millen (2008b). Bottom panel shows how each participant’s observation (blue) and building (yellow) stages were staggered relative to other members of their microsociety.

Figure 1 displays the data for both the paper aeroplane task and the spaghetti tower task, which supported our basic expectation of a ratchet-like effect across multiple successive learners. Effectively, the learning opportunities available to participants appeared to permit generational carry-over of the experience of past members of the microsociety, such that learners (given exactly the same instructions, materials, and time constraints) could perform better if they were placed in later generations.

Does Cumulative Culture Depend on Imitation?

Although Caldwell and Millen’s (2008b) study showed that it was possible to capture cumulative cultural evolution under laboratory conditions, it was unclear what information participants were using to generate this effect. However, these methods permitted manipulation of the information available to learners to address this question. Dominant theoretical perspectives on cumulative culture proposed that imitation and teaching were required for it to occur (e.g. Tomasello et al., 1993; Tennie et al., 2009). Although definitions of imitation are widely debated within comparative psychology (Caldwell & Whiten, 2002), there is general consensus that it requires observation of another’s behaviour, and that it should result in some detectable match between the actions of the model and those of the observer. Early studies which failed to find evidence of such action copying in nonhuman species (e.g. monkeys: Visalberghi & Fragaszy, 1990; apes: Tomasello, Davis-Dasilva, Camak & Bard, 1987) gave credence to the view that this might provide an explanation for the absence of cumulative culture in nonhumans. However, later studies which identified copying of specific techniques (e.g. using “two-action” experimental designs) in a range of nonhuman species (e.g. see Whiten, Horner, Litchfield & Marshall-Pescini, 2004, for a review of evidence in apes) cast some doubt on the validity of this interpretation (although evidence of imitation in nonhumans continues to be debated, e.g. Tennie et al., 2009).

Consistent with this, further experimental studies of cumulative culture in humans demonstrated that action copying may not be strictly required. Through manipulation of the information available to learners in particular microsocieties, Caldwell and Millen (2009) found that participants were capable of generating cumulative culture even when information about others’ actions was not available. In the paper aeroplane task, when members of the microsocieties received information only about results (flight distances) and end products (completed planes), without opportunities to observe others building, they still showed cumulative increases in performance over generations.

In this particular task performance scores were primarily determined by the physical structure of the artefacts produced, and those structures were relatively easy to reproduce from inspecting the finished products. For other tasks, reproduction of specific behaviours may of course be necessary in order to generate improvements in performance over generations (e.g. knot tying, for which it is often difficult to infer the required steps on the basis of the finished product alone). And for some skills, active instruction may also be required in order to correct mistakes, shape behaviour, and explain underlying principles (e.g. food preparation techniques which remove undetectable toxins, whose function may be opaque to an observer). Nonetheless, it seems clear that cumulative culture can occur in the absence of opportunities for action copying, and so this in itself does not provide a comprehensive explanation for the absence of cumulative culture in nonhumans.

The question of the specific cognitive differences explaining the uniqueness of human cumulative culture currently remains unresolved. However, future research will likely benefit from an approach which considers particularities of the ways that human learners process and use social information irrespective of source.

How Does Cultural Evolution Shape Resulting Behaviours?

In addition to clarifying the conditions necessary for cumulative cultural evolution to occur, experimental approaches have also been used to investigate factors influencing the outcomes of this process in terms of the resulting behaviours. It is likely that such behaviours are shaped in particular ways by repeated social transmission. Experimental work has begun to investigate how cultural traits tend to transform over multiple learner generations. This has been demonstrated most clearly in studies of artificial language learning (e.g. Kirby, Cornish & Smith, 2008; Kirby, Tamariz, Cornish and Smith, 2015). In these experiments participants are trained on a set of novel labels with corresponding stimuli representing their meanings. They are then tested, and this output is used as training data for the next participant. Kirby et al. (2015) found that sets of labels changed to become more internally structured, i.e. each label became increasingly predictable from other labels assigned to related meanings. In this way, the language evolved to become more learnable over the repeated generations of transmission. This only happened, however, in chains of participant pairs who learned their labels from preceding pairs. It did not occur in a control condition in which communicating pairs completed the same task, but did so over multiple sessions with the same partner, receiving their own output from the most recent session as training for the next. In the absence of new learners, the languages did not adapt to become more learnable.

Whilst the cultural evolution of language might not represent a prototypical case of cumulative cultural evolution as we have defined it, it is likely that similar effects occur in other contexts. We should therefore expect that pressures for learnability will shape the attributes of other culturally transmitted behaviours in particular ways, which may be unrelated to, or even in conflict with, other functional pressures.

Following this logic, it is also likely that differences in the transmission processes involved in the ancestral histories of cultural traditions can affect the eventual forms of behaviour. So, for example, differences in population size or structure may influence the level of complexity of the traits which can persist, as a consequence of the availability of learning opportunities and the likelihood of exposure resulting in accurate transmission. Larger and/or more densely connected populations are assumed to be less vulnerable to losing complex skills which may only rarely be successfully transmitted, due to the increased probability of encounters between proficient individuals and potential learners (Henrich, 2004; Powell, Shennan & Thomas, 2009). Hard-to-learn skills might therefore only ratchet up in well-connected populations which ensure exposure to a diversity of potential models.

Muthukrishna, Shulman, Vasilescu and Henrich (2014) tested this hypothesis experimentally by asking participants to use image editing software to produce a complex target image, and evaluating the effectiveness of the attempts of ten generations of learners. They compared conditions in which learners were exposed to information about how to complete the task from either one member, or five members, of the previous generation. In line with predictions, the images created by participants in the five-model condition showed improvement over generations whereas those in the one-model condition did not (see also Derex, Beugin, Godelle & Raymond, 2013, for an experimental test of the group size hypothesis without generational replacement).

Outstanding Issues

Although experimental methods have permitted significant insights into cumulative culture, a number of key questions remain unanswered. For example, although there is little evidence of cumulative culture occurring spontaneously in nonhumans, it remains to be seen whether it is possible to find performance increases over transmission under experimental conditions similar to those described previously for studies of human participants. Under favourable laboratory conditions (probably involving relatively well-trained animal subjects and target behaviours which are comfortably inside their performance repertoire) it may be possible to elicit similar effects. If this turns out to be the case then researchers face a further question regarding the barriers limiting cumulative culture in naturally occurring behaviours.

Along similar lines, questions remain over the extent to which particular transmission mechanisms may be necessary depending on the behaviour in question. For example, given that teaching appears to be uniquely flexible in humans, if not strictly unique (e.g. Kline, 2015), is it necessary for the transmission of certain behaviours? And if so, does this help us to re-construct a co-evolutionary sequence of mutually reinforcing adaptive pressures between the early existence of relatively complex cultural artefacts, the evolution of human pedagogy, and the resulting effects on the cultural traits that could be transmitted? It is likely that approaches similar to those discussed in the current article will contribute to the eventual resolution of some of these important outstanding issues.

Recommended Readings.

Caldwell, C. A. & Millen, A. E. (2008a). (See References). A more detailed discussion of the advantages of experimental approaches, relative to alternatives, as a method for studying cumulative cultural evolution.

Caldwell, C. A. & Millen, A. E. (2008b). (See References). The source of some of the empirical work discussed here, establishing the feasibility of using experimental microsociety methods to study cumulative culture.

Dean, L. G., Vale, G. L., Laland, K. N., Flynn, E. G., & Kendal, R. L. (2014). (See References). A review of the evidence of cumulative culture in animals which concludes with a view alternative to the one presented in the current paper.

Whiten, A., Caldwell, C. A., & Mesoudi, A. (2016). (See References). A comprehensive review of experimental studies of cultural evolution in humans and nonhumans, not restricted to the topic of cumulative culture.

Acknowledgements and End Note

The research reported here was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (RES-061-23-0072 and RES-062-23-1634). CC, MA and ER are supported by a Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council.

References

- Baum WM, Richerson PJ, Efferson CM, Paciotti BM. Cultural evolution in laboratory microsocieties including traditions of rule giving and rule following. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2004;25:305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Why culture is common, but cultural evolution is rare. Proceedings of the British Academy. 1996;88:77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd R, Richerson PJ, Henrich J. The cultural niche: why social learning is essential for human adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2011;108:10918–10925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100290108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CA, Millen AE. Studying cumulative cultural evolution in the laboratory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2008a;363:3529–3539. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CA, Millen AE. Experimental models for testing hypotheses about cumulative cultural evolution. Evolution and Human Behaviour. 2008b;29:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CA, Millen AE. Social learning mechanisms and cumulative cultural evolution: Is imitation necessary? Psychological Science. 2009;20:1478–1483. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CA, Whiten A. Evolutionary perspectives on imitation: is a comparative psychology of social learning possible? Animal Cognition. 2002;5:193–208. doi: 10.1007/s10071-002-0151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean LG, Vale GL, Laland KN, Flynn EG, Kendal RL. Human cumulative culture: A comparative perspective. Biological Reviews. 2014;89:284–301. doi: 10.1111/brv.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derex M, Beugin MP, Godelle B, Raymond M. Experimental evidence for the influence of group size on cultural complexity. Nature. 2013;503:389–391. doi: 10.1038/nature12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J. Demography and cultural evolution: How adaptive cultural processes can produce maladaptive losses: The Tasmanian case. American Antiquity. 2004;69:197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Heyes CM. Social learning in animals: Categories and mechanisms. Biological Reviews. 1994;69:207–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1994.tb01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RC, Campbell DT. The perpetuation of an arbitrary tradition through several generations of laboratory microculture. Journal of Abnormal and social Psychology. 1961;62:649–658. doi: 10.1037/h0044182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby S, Cornish H, Smith K. Cumulative cultural evolution in the laboratory: An experimental approach to the origins of structure in human language. PNAS. 2008;105:10681–10686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707835105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby S, Tamariz M, Cornish H, Smith K. Compression and communication in the cultural evolution of linguistic structure. Cognition. 2015;141:87–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline MA. How to learn about teaching: An evolutionary framework for the study of teaching behavior in humans and other animals. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2015;38:1–71. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X14000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukrishna M, Shulman BW, Vasilescu V, Henrich J. Sociality influences cultural complexity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2014;281:20132511. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell A, Shennan S, Thomas MG. Late Pleistocene demography and the appearance of modern human behaviour. Science. 2009;324:1298–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1170165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennie C, Call J, Tomasello M. Ratcheting up the ratchet: On the evolution of cumulative culture. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 2009;364:2405–2415. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Davis-Dasilva M, Camak L, Bard K. Observational learning of tool use by young chimpanzees. Human Evolution. 1987;2:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Kruger AC, Ratner HH. Cultural learning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1993;16:495–552. [Google Scholar]

- Visalberghi E, Fragaszy DM. Do monkeys ape? In: Parker ST, Gibson KR, editors. “Language” and Intelligence in Monkeys and Apes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 247–273. [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A, Caldwell CA, Mesoudi A. Current opinion in Psychology. 2016;8:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A, Horner V, Litchfield CA, Marshall-Pescini S. How do apes ape? Learning and Behavior. 2004;32:36–52. doi: 10.3758/bf03196005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]