Abstract

There is lack of studies assessing the preference of Indian patients for integration of homeopathy into standard therapy settings. The objectives of this study were to examine the knowledge, attitudes, and practice of homeopathy among Indian patients already availing homeopathy treatment and its integration into mainstream healthcare.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among adult patients attending the out-patients of the four government homeopathic hospitals in West Bengal, India. A self-administered 24-items questionnaire in local vernacular Bengali was developed and administered to the patients.

A total of 1352 patients' responses were included in the current analysis. 40% patients thought that homeopathic medicines can be used along with standard therapy. 32.5% thought that homeopathic medicines might cause side effects, while only 13.3% believed that those might interact with other medications. Patients' knowledge ranged between 25.1 and 76.5% regarding regulations of practicing and safety of homeopathic medicine in India and abroad; while positive attitude towards the same ranged between 25.4 and 88.5%. 88.6% of the patients had favorable attitude toward integrated services. 68.2% of the patients used homeopathic medicines in any acute or chronic illness for themselves and 76.6% for their children. Preference for integrated services was significantly associated with better knowledge (P = 0.002), positive attitudes toward safety and regulations (P < 0.0001), and integration (P < 0.0001), but not with the level of practice (P = 0.515).

A favorable attitude toward integrating homeopathy into conventional healthcare settings was obtained among the patients attending the homeopathic hospitals in West Bengal, India.

Keywords: homeopathy, integrative medicine, India, patients' preference, attitude

Graphical abstract

Name of the Institutions where the work was primarily carried out:

-

•

Midnapore Homeopathic Medical College & Hospital, Government of West Bengal; Post Office Midnapore, Midnapore (West) 721101, West Bengal, India

-

•

D N De Homeopathic Medical College & Hospital; 12, Gobinda Khatick Road, Kolkata 700046, West Bengal, India

-

•

The Calcutta Homeopathic Medical College & Hospital, Government of West Bengal; 265, 266, Acharya Prafulla Chandra Road, Kolkata 700009, West Bengal, India

-

•

Mahesh Bhattacharya Homeopathic Medical College & Hospital, Government of West Bengal; Drainage Canal Road, Doomurjala, Howrah 711104, West Bengal, India

1. Introduction

Traditional and Complementary Medicine (TCM; 傳統暨替代醫學 chuán tǒng jì tì dài yī xué) is a method that can enrich, strengthen the public health system and improve the quality of life; contribute to the quality of economic and social development; improve the health and development of local communities; safeguard cultural differences; focus attention on healthcare centres intended as physical, mental, spiritual and social well-being of people, nature and environment.1 Since origin, it has a patient-centered approach and a holistic focus on health care instead of a disease-centered approach of conventional medicine.2 It represents a useful and sustainable resource in different fields of health care; but their inclusion in the public health system must go hand in hand with an adequate process of scientific evaluation to control the efficacy, safety and quality of the health services and products.3 However, patient preference for the same is also of considerable importance for the development and success of integrated services.

In India, the endeavour of mainstreaming TCM, namely AYUSH [Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, Homeopathy, and Amchi/Sowa Rigpa (Tibetan medicine); renamed in November 2003; previously called ISM&H, i.e. Indian System of Medicine and Homeopathy, created in March 1995] therapies is ongoing through formulation of the National Policy on ISM&H in 2002 and implementation of different schemes, e.g. National (Rural/Urban) Health Mission (N(R/U)HM) since 2005, Homeopathy Specialty Clinics since 2009, Reproductive and Child Health (RCH) and Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) since 2012, etc. Establishment of ISM&H dispensaries under the Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS) is ongoing since 1964 for ayurveda and since 1967–68 for homeopathy.4 The objective of the integration of AYUSH in the health care infrastructure was to reinforce the existing public health care delivery system, with the use of natural, safe and friendly remedies, which are time tested, accessible and affordable, and to improve outreach and quality of health delivery in rural areas. Homeopathic services are still being integrated in different primary health center settings, divisional, sub-divisional and district hospitals and even apex institutions, like All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS Raipur, AIIMS Bhubaneswar), Safdarjung Hospital, and Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital, New Delhi etc. As on March 2014, in West Bengal, India, there are 545 State Homeopathic Dispensaries (SHDs), 975 Gram Panchayet Homeopathic Dispensaries, 14 Specialty Clinics, and 4 Homeopathy Wings – all integrated into conventional care services.5

However, there is lack of studies assessing the preference of Indian patients for the integrated services. The study was the first local study to assess patients' demand of integrated medical services. We intend to assess: (1) preference for integrated services of the patients already availing services from homeopathy hospitals (part 1); (2) satisfaction of patients from integrated services (part 2); and (3) preference for integration where integrated service is not available (part 3). This paper presents the results of the part 1 study. The objective was to examine the knowledge, attitudes, and practice of patients toward homeopathy as well as to assess their preference for integration of homeopathy into mainstream health care.

2. Materials methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted on the patients visiting out-patients of the four government homeopathic hospitals in West Bengal, India, namely Midnapore Homeopathic Medical College & Hospital (MHMC&H), D N De Homeopathic Medical College & Hospital (DNDHMC&H), Calcutta Homeopathic Medical College & Hospital (CHMC&H), and Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homeopathic Medical College & Hospital (MBHMC&H). Permission was granted from the institutional ethics committees of each respective institution prior to conducting the study. The study was of 3 months duration – August to October 2014.

Inclusion criteria were the patients aged 18 years and above, and giving written informed consent to take part in the study. Exclusion criteria were patients who were too sick for consultation, unable to read patient information sheets, unwilling to participate, and not giving consent to join the survey. Systematic sampling method was used to select every 3rd patient as a respondent in each setting. Following distribution of patient information sheets and explanation of the study objectives, written informed consents were obtained from all patients. The questionnaire was distributed among 1435 patients, of whom, 1352 returned the filled-in questionnaire, and thus response rate was 94.2%.

No universally accepted standardized questionnaire in local vernacular Bengali was available for the purpose. We used one self-administrated questionnaire that was originally developed by Allam S, et al, 2014.6 It was modified with due permission as per homeopathic perspective and translated and back-translated in standard procedure independently by two translators in local vernacular Bengali (Fig. 1). It included 2 sections: socio-demographic information and 24 questions assessing the patient's knowledge, attitudes, and practice of homeopathic medicine and its integration into mainstream services.

Fig. 1.

Translation and adaptation sequence of the used Bengali questionnaire.

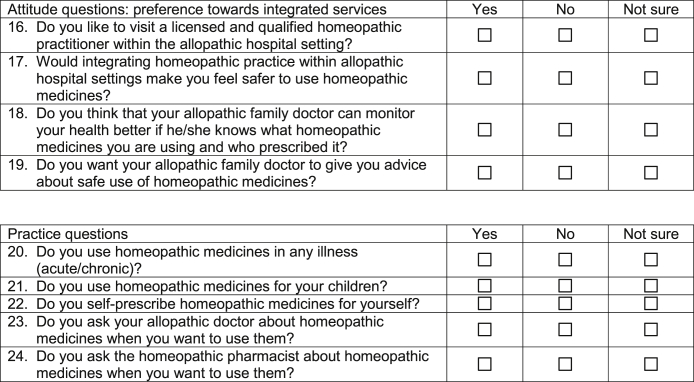

Socio-demographic data sought information regarding the out-patient visited, age, sex, marital status, educational level, employment status, and monthly income. The knowledge part included 7 questions about concurrent use of homeopathic medicines with standard therapies, side effects, interactions, local and international governing regulations, and awareness of a Western model of integration. The attitude part included 12 questions divided into 2 groups: 8 questions about the regulations and the safety of homeopathic medicine and 4 questions about the preference for integrated services. The practice part included 5 questions about one's experience using homeopathic medicine and its integration. All the 24 questions were provided with 3 answering options – ‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘not sure’. The questionnaire was piloted on a small number of patients (n = 10) to identify potential areas of misinterpretation before widespread distribution. The wording of questions was modified as per the feedback from the pilot sample. The questionnaire took 5–7 min to complete. Instructions on the questionnaire promised anonymity. No participant identifiable information was required, thus protecting privacy. In addition, the completed questionnaires were concealed inside opaque envelopes, which were sealed at the survey site by patients themselves. All survey forms were collected by the research assistants and were sent for data analysis. (Annexure 1, Annexure 2: English and Bengali versions of the used questionnaire).

A specially designed excel sheet was used for data extraction and was subjected to statistical analysis using different computation websites (Fig. 2). Descriptive statistics were presented through frequencies and percentages for categorical data, and mean ± standard deviation for continuous data. Scores were calculated from the knowledge, attitudes, and practice questions. A point was given for the ‘yes’ answer and a zero for the ‘no’ and ‘not sure’ answers. Patients answering ‘yes’ to questions no. 16 were considered demanding the integration. Differences in socio-demographic characteristics and scores between the study groups (those who prefer and do not prefer integration of homeopathy into conventional services) were tested through the chi-square test for categorical data and student t test for continuous data. All P values were 2-tailed. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Fig. 2.

Study flow diagram.

3. Results

Mean age of the survey respondents was 39.8 years (standard deviation 15.6). The participants spanned 31–50 years (523, 38.7%) and 18–30 years (489, 36.2%) of age-groups mostly, with almost equal gender distribution (female 51.9%, male 48.1%). The patients were mostly married (924, 68.3%), student and dependent (581, 42.9%), belonged from lower income group families (796, 58.9%), and had education level of 10th standard or less (488, 36.1%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and distribution of knowledge, attitude, and practice scores (N = 1352).

| Variables | Overall | Preference for integrating homeopathy |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No/Not sure | P value | ||

| Total responses | 1352 (100) | 1198 (88.6) | 154 (11.4) | – |

| Age (years)Ұ: | 39.8 ± 15.6 | 39.7 ± 15.5 | 40.5 ± 16.1 | 0.188 |

| Age groups#: | ||||

| 18–30 | 489 (36.2) | 437 (89.4) | 52 (10.6) | 0.891 |

| 31–50 | 523 (38.7) | 464 (88.7) | 59 (11.3) | |

| 51–70 | 308 (22.8) | 270 (87.7) | 38 (12.3) | |

| ≥70 | 32 (2.4) | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) | |

| Sex#: | ||||

| Female | 702 (51.9) | 619 (88.2) | 83 (11.8) | 0.664 |

| Male | 650 (48.1) | 579 (89.1) | 71 (10.9) | |

| Marital status#: | ||||

| Married | 922 (68.3) | 819 (88.8) | 103 (11.2) | 0.408 |

| Unmarried | 407 (30.2) | 357 (87.7) | 50 (12.3) | |

| Others | 20 (1.5) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Occupation#: | ||||

| Student and dependent | 555 (43.2) | 506 (91.2) | 49 (8.8) | 0.066 |

| Self-employed | 448 (34.9) | 394 (87.9) | 54 (12.1) | |

| Service | 282 (21.9) | 245 (86.9) | 37 (13.1) | |

| Monthly household income (Rs.)#: | ||||

| ≤ 10,000 | 761 (59.0) | 667 (87.6) | 94 (12.4) | 0.113 |

| 10,000–30,000 | 425 (32.9) | 388 (91.3) | 37 (8.7) | |

| >30,000 | 103 (7.9) | 89 (86.4) | 14 (13.6) | |

| Education#: | ||||

| 10th standard or less | 486 (36.4) | 430 (88.5) | 56 (11.5) | 0.980 |

| 12th standard | 357 (26.7) | 316 (88.5) | 41 (11.5) | |

| Graduate or above | 494 (36.9) | 442 (89.5) | 52 (10.5) | |

| ScoresҰ: | ||||

| Knowledge | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 0.002* |

| Attitude toward regulations | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 5.0 ± 1.7 | 0.000* |

| Attitude toward integration | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 0.000* |

| Practice | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 0.515 |

ҰContinuous data presented as mean ± standard deviation and independent t test applied; # categorical data presented as N (%) and chi-square test (Yates corrected) applied; *P < 0.05 two-tailed considered as statistically significant.

Overall, 1198 (88.6%) patients preferred integration of homeopathy within conventional health setups, whereas 154 (11.4%) didn't prefer so or were not sure. Knowledge score was compromised; mean 2.7 (sd 1.5); 38.6% of the maximum score. Attitude scores were comparatively high. Mean attitude score towards regulation of practice and safety of homeopathic medicines was 5.6 (sd 1.6), 70% of the maximum score. Similarly, mean attitude score towards integration of homeopathy within conventional healthcare setups was 2.4 (sd 1.2); 60% of the maximum score. Mean practice score was 2.2 (sd 1.1); 44% of the maximum score (Table 1).

Preference scores for integrated services did not seem to be influenced by age (t = *−1.3; P = 0.188), age groups [χ2 = 0.622 (Yates corrected); P = 0.891 (Yates corrected)], gender [χ2 = 0.189; P = 0.664], marital status [χ2 = 1.795; P = 0.408], occupation [χ2 = 5.451; P = 0.066], income status [χ2 = 4.354; P = 0.113], and educational standing [χ2 = 0.04; P = 0.980]. However, favorable attitude towards integration was significantly associated with higher knowledge score [t = 3.115; P = 0.002], attitude score towards regulation and safety [t = 4.123; P < 0.0001], and attitude score towards preference for integrated services [t = 18.944; P < 0.0001]; but not with practice scores [t = 0.652; P = 0.515] (Table 1).

541 (40%) patients thought that homeopathic medicines can be used along with standard therapy. 439 (32.5%) patients thought that homeopathic medicines might cause side effects, while only 180 (13.3%) believed that those might interact with other medications. 1034 (76.5%) patients were aware of license for homeopathic practitioners in Indian system of health and 821 (60.7%) knew about laws of regulating homeopathic practices in India. Comparatively, knowledge regarding integrated services (n = 339; 25.1%) and similar laws (n = 541; 40%) in developed countries were compromised (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patients' knowledge, attitudes, and practice towards integrated healthcare (N = 1352).

| Questionnaire | Yes | No | Not sure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge: | |||

| 1. Homeopathic medicines may be used along with standard therapy. | 541 (40.0) | 609 (45.0) | 202 (14.9) |

| 2. Homeopathic medicines may cause side effect. | 439 (32.5) | 913 (67.5) | 247 (18.3) |

| 3. Homeopathic medicines may interact with other medications. | 180 (13.3) | 833 (61.6) | 339 (25.1) |

| 4. There is license for homeopathic practitioners in Indian system of health. | 1034 (76.5) | 82 (6.1) | 236 (17.5) |

| 5. There is law to regulate homeopathic practices in India. | 821 (60.7) | 136 (10.1) | 395 (29.2) |

| 6. There is law to regulate homeopathic practices in developed countries like USA, Canada, and Germany. | 541 (40.0) | 113 (8.4) | 698 (51.6) |

| 7. There is integrative homeopathic consultation within hospital settings in developed countries like USA, Canada, and Germany. | 339 (25.1) | 202 (14.9) | 811 (59.9) |

| Attitude questions: Regulations of practicing and safety of homeopathic medicine | |||

| 8. Homeopathic practitioners should have degree in this profession. | 1196 (88.5) | 38 (2.8) | 118 (8.7) |

| 9. The homeopathic practitioners should be certified and licensed from the Ministry of Health. | 1103 (81.6) | 46 (3.4) | 203 (15.0) |

| 10. The production and selling of homeopathic medicines should be regulated by the government. | 1140 (84.3) | 72 (5.3) | 140 (10.4) |

| 11. The homeopathic medicine container should have a license and registration number. | 521 (38.5) | 478 (35.4) | 353 (26.1) |

| 12. The homeopathic medicine container should be labelled with the expiry date. | 1118 (82.7) | 126 (9.3) | 108 (7.9) |

| 13. The homeopathic medicine container should have a warning of possible side effect and interaction with other medications. | 987 (73.0) | 149 (11.0) | 216 (15.9) |

| 14. The homeopathic medicine container should have a clear note of approval by the government drug control authority. | 1118 (82.7) | 94 (6.9) | 140 (10.4) |

| 15. Homeopathic pharmacist can give useful advice regarding use of homeopathic medicines. | 344 (25.4) | 761 (56.3) | 247 (18.3) |

| Attitude towards integration: Preference for integration of homeopathy within conventional care settings | |||

| 16. Would like to visit a licensed and qualified homeopathic practitioner within the allopathic hospital setting. | 1198 (88.6) | 104 (7.7) | 50 (3.7) |

| 17. Integrating homeopathic practice within allopathic hospital would make feel safer to use homeopathic medicines. | 795 (58.8) | 261 (19.3) | 296 (21.9) |

| 18. Allopathic doctors can monitor health better if they know what homeopathic medicines are being used. | 628 (46.4) | 401 (29.7) | 323 (23.9) |

| 19. Allopathic doctors should give advice about safe use of homeopathic medicines. | 659 (48.7) | 562 (41.6) | 131 (9.7) |

| Practice questions | |||

| 20. Use homeopathic medicines in any illness (acute/chronic). | 922 (68.2) | 363 (26.8) | 67 (4.9) |

| 21. Use homeopathic medicines for children. | 1035 (76.6) | 207 (15.3) | 110 (8.1) |

| 22. Self-medicate with homeopathic medicines. | 213 (15.8) | 1055 (78.0) | 84 (6.2) |

| 23. Would ask allopathic doctors about homeopathic medicines when wants to use them. | 563 (41.6) | 659 (48.7) | 130 (9.6) |

| 24. Would ask homeopathic pharmacists about homeopathic medicines when wants to use them. | 260 (19.2) | 917 (67.8) | 175 (12.9) |

Attitude towards law-regulated practice and safety of homeopathic medicine was quite favorable. 1196 (88.5%) opted for having professional degrees for homeopathy practitioners and 1103 (81.6%) preferred them to be certified from the Ministry of Health. 1140 (84.3%) patients opined for government regulated production and selling of homeopathic medicines. 1118 (82.7%) respondents desired the homeopathic medicine containers to be labelled with expiry date, 521 (38.5%) thought that the containers should contain license and registration number. 987 (73%) wanted the containers to mention warning of possible side effects, and 1118 (82.7%) wished clear note of approval by the government drug control authority on the container. Only 344 (25.4%) patients thought that homeopathic pharmacists could give useful advice regarding use of homeopathic medicines (Table 2).

1198 (88.6%) patients had preference to visit a licensed and qualified homeopathic practitioner within conventional healthcare setups, and 795 (58.8%) disclosed that they would feel safer to use homeopathic treatment following integration. However, the matter of integrating homeopathy within the conventional curriculum remained questionable. Only 628 (46.4%) thought that the allopathic doctor could monitor health better being aware of the homeopathic medicine(s) being used by the patient(s), and 659 (48.7%) thought the allopathic doctors to be competent of giving advice about safe use of homeopathic medicines (Table 2).

922 (68.2%) patients claimed to use homeopathic medicines in any illness – either acute or chronic, and the declared use in case of children rose to 1035 (76.6%). Only 213 (15.8%) patients admitted of self-medication with homeopathic medicines. 563 (41.6%) and 260 (19.2%) respondents asked allopathic doctors and homeopathic pharmacists respectively about homeopathic medicines when they wanted to use them (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Majority of the patients revealed favorable attitude toward integrating homeopathy into conventional healthcare settings. Preference for integrated services was significantly associated with better knowledge, positive attitudes toward safety and regulations, and integration, but not with the level of practice. Surprisingly, knowledge of homeopathy was compromised even among the patients availing homeopathy treatment from the homeopathic hospitals. This may be attributable to insufficient display of the available services and facilities by the homeopathic hospitals, as identified by a recent study.7

This study did not incorporate the perspectives of health care professionals; rather relied solely on the opinions of patients. Our study was also limited in the sense that the respondents who were absent in the days of the survey, might have scored differently. Besides, cross-sectional design of the study impedes to draw any causative conclusions. No formal validation of the used Bengali questionnaire was carried out. More specific statistical (Rasch) analysis is required to confirm whether the sequence of the original questionnaire will require any readjustment. Despite the limitations, the results seemed to be quite generalizable in homeopathy hospitals across India. Selection bias was minimized by systematic sampling method. Alongside, this study offered an insight into an extremely important issue, which is supposed to be a matter of extensive discussions with a view to formulate a common policy.

The growing popularity of TCM (傳統暨替代醫學 chuán tǒng jì tì dài yī xué) resulted in an ongoing debate on integrating such therapies into the mainstream healthcare.8 The World Health Organization (WHO) supported incorporation of TCM into national health care systems9 and stressed integration at the community level to guarantee its judicious use.10, 11 Integration of TCM in primary care services was reported in a number of studies from the United States, Germany, Israel, Australia, Italy, and Iran.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 In the Western model of integration, TCM is practiced mostly as specialty that allowed physicians to address body-mind-emotional and spiritual causes of disease. Additional TCM experience gave them flexibility to offer patients different treatment options and alleviated the need to reconcile conflicting theories of disease etiology.18 Some of the early field-based studies by the WHO in Ghana, Mexico, and Bangladesh to evaluate the effectiveness of CAM practitioners as primary health care workers were shown to be effective.19 This made the ground for integrating CAM into primary health care.

In the point of view of developing countries' inadequate human resources for health, the existing CAM practitioners can be added to the existing pool of human resources for conventional medicine. The health workforce in India is unevenly distributed, with a shortage of doctors in rural areas. However, this needs to be guided by a properly functioning regulatory body and strategies that promote rational integration from grassroots level.20

Homeopathy in India has established itself more than anywhere else in the world. It is regulated through central acts and statutory regulatory body and a large infrastructure in the form of registered practitioners, teaching institutions, dispensaries and hospitals. The Department of AYUSH is headed by a Secretary to the Government of India. The Secretary is assisted by a Joint Secretary and four Directors/Deputy Secretaries and a number of Advisers and Dy. Advisors of AYUSH.

As on April 1, 2010, the homeopathy infrastructure of AYUSH in the country consisted of 245 hospitals, 9631 beds, 6958 dispensaries, and 246,772 registered practitioners. 185 undergraduate (UG) colleges with 12,371 intake capacity, 33 postgraduate (PG) colleges with 1073 intake capacity, and 2 exclusive PG colleges with 99 intake capacity.21 The infrastructure in West Bengal consisted of 12 hospitals, 630 beds, 1534 dispensaries, 41,079 registered practitioners, 13 UG colleges (4 undertaken by the Govt. of West Bengal, 1 by the Govt. of India, rest private; all under affiliation with the West Bengal University of Health Sciences/WBUHS) with 693 intake capacity, 3 PG colleges (2 run by the Govt. of West Bengal, 1 by the Govt. of India, under WBUHS) with 30 intake capacity, and 105 licensed pharmacies.22 The Central Council for Research in Homeopathy (CCRH) also runs one clinical research unit (CRU), and one regional research institute (RRI) in West Bengal.23

The strength of the AYUSH system lies in promotive, preventive & rehabilitative health care, diseases and health conditions relating to women and children, mental health, stress management, problems relating to older person, non-communicable diseases etc. While AYUSH should contribute to the overall health sector by meeting national health outcome goals, the department should retain primary focus on its above mentioned core competencies. The Steering Committee Report for the 12th five year plan recommended enhanced funding, improved networking, establishing a national registry of all AYUSH research studies, support for research scholars, introduction of National Eligibility Test for research fellows, establishment of National AYUSH Mission, All India Institute of Homeopathy, Homeopathic Medicines Pharmaceutical Corporation Limited (HPCL), AYUSH Telemedicine Services, and AYUSH Gram, launch of AYUSH fellowship scheme and National AYUSH health programs, increased cultivation of medicinal plants, regulation of pharmacopeia standards and Information Technology, development of, Setting up of Research and Quality Control Laboratories in 8 National Institutes, and further integration of AYUSH with different national schemes; e.g. Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), early breastfeeding, growth monitoring of children, ante and post natal care, normal labor etc.24

Though the administration of AYUSH is still in developmental phase in India, initiatives for mainstreaming have remained sub-optimal, and thus implementation status ‘poor’. AYUSH therapies have constantly been criticized for lack of quality education and accreditation, poor administrative set-ups and vigilance, continuous negligence, substandard research, absence of any transparent strategy or protocols for goal oriented role and responsibility, lack of leadership and public awareness, corruption, and inadequate budget.25, 26 AYUSH therapies need to be integrated without compromising diversity and unique aspects.27 There are recommendations to use homeopathic workforce in public health also.25 In a recent study, majority of experts opined that ISM&H Policy should be merged to form unified health policy as health is a complete concept in itself and should be viewed in multidisciplinary approach.28 Still, there are several challenges, including physician concern, utilization issues, and system adjustment.29 One recent study identified discriminatory attitude at the workplace and lack of legal/regulatory authorization as task-shifting challenges by AYUSH practitioners working as skilled birth attendance (SBA) in 3 states (Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Odisha) of India.30

Future research is already underway studying satisfaction of patients from integrated services (part 2), and preference for integration where integrated service is not available (part 3). More research is necessary to determine how physicians are choosing to integrate CAM theories of disease and therapeutic practices into biomedical practice. Future research should expand the research methods to include patients' responses to treatment and long-term follow-up to determine the extent to which patients could use the advice given in similar setups.

5. Conclusion

Patients preferred for integration of homeopathy within conventional health setups. Still, the process of integration is facing difficulties, from the level of policy formulation to implementation. Many recommendations are being made, and what is needed at this moment, is a sincere authority, a transparent policy, and a dedicated, eligible workforce aimed at promulgation of TCM (傳統暨替代醫學 chuán tǒng jì tì dài yī xué) in India.

Author contributions

Munmun Koley, Subhranil Saha, Jogendra Singh Arya, Gurudev Choubey: Concept, design, literature search, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation. Aloke Ghosh, Kaushik Deb Das, Subhasish Ganguly, Samit Dey, Sangita Saha, Rakesh Singh, Kajal Bhattacharyya, Shubhamoy Ghosh, Sk. Swaif Ali: Data acquisition and master chart preparation. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Chapal Kanti Bhattacharyya, Principal in-Charge, MHMC&H; Dr. Akhilesh Khan, Principal in-Charge, DNDHMC&H; and Dr. Nikhil Saha, Principal in-Charge, MBHMC&H for allowing us to carry out the project successfully in their institutions. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Monojit Kundu, Dr. Ramkumar Mondal, (Dr.) Supratim Patra, Ms. Tanapa Banerjee, Mr. Arijit Manna for their cooperation in data collection and master chart preparation. The authors would like to thank the patients for their participation in the study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

Contributor Information

Munmun Koley, Email: dr.mkoley@gmail.com.

Subhranil Saha, Email: drsubhranilsaha@hotmail.com.

Jogendra Singh Arya, Email: jogendraarya2007@rediffmail.com.

Gurudev Choubey, Email: gurudev.choubey@gmail.com.

Aloke Ghosh, Email: dralok_ghosh@yahoo.com.

Kaushik Deb Das, Email: drkaushikddas75@gmail.com.

Subhasish Ganguly, Email: ganguly.subhasish@rediffmail.com.

Samit Dey, Email: dr.samit@yahoo.com.

Sangita Saha, Email: dr.sangita@rediffmail.com.

Rakesh Singh, Email: singhdrrakesh@yahoo.in.

Kajal Bhattacharyya, Email: kaybee_1958@rediffmail.com.

Shubhamoy Ghosh, Email: shubhamoy67@gmail.com.

Sk. Swaif Ali, Email: swaifali93@gmail.com.

Annexure 1. English version of the used questionnaire.

Annexure 2. Bengali version of the used questionnaire.

References

- 1.Florence Declaration Complementary and Traditional Medicine in Public Health: Towards an Integral Health System. International Workshop Innovation and Development in Health: Integration of Complementary and Traditional Medicine in Public Health Systems, Florence October 28–31, 2008. http://www.art-tuscany.org/documents/reports/MedCom_DeclarationEng.pdf; Accessed 03.12.14.

- 2.Astin J.A. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossi E., Di Stefano M., Baccetti S. International cooperation in support of homeopathy and complementary medicine in developing countries: the Tuscan experience. Homeopathy. 2010;99:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Report no. 16 of 2005: Performance Audit report on AYUSH. Dept. of AYUSH, Ministry of Health & family welfare. Available at http://saiindia.gov.in/english/home/our_products/audit_report/government_wise/union_audit/recent_reports/union_performance/2004_2005/Civil_%20Performance_Audits/Report_no_16/perfaudayush.pdf; Accessed 03.12.14.

- 5.Health on the March 2012–2013. State Bureau of Health Intelligence, Directorate of Health Services, Govt. of West Bengal. Available at: http://www.wbhealth.gov.in/medical-directory/Health%20on%20March%20Book%202013.pdf; Accessed 03.12.14.

- 6.Allam S., Moharam M., Alarfaj G. Assessing patients' preference for integrating herbal medicine within primary care services in Saudi Arabia. J Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2014;19:205–210. doi: 10.1177/2156587214531486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koley M., Saha S., Arya J.S. Patient evaluation of service quality in government homeopathic hospitals in West Bengal, India: a cross-sectional survey. Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2015;20:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas K.J., Coleman P., Weatherley-Jones E. Developing integrated CAM services in primary care organisations. Complement Ther Med. 2003;11:261–267. doi: 10.1016/s0965-2299(03)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akerele O. The best of both worlds: bringing traditional medicine up to date. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24:177–181. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi C. Integrating traditional medicine into modern health care systems: examining the role of Chinese medicine in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:307–321. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary/alternative medicine: a worldwide review. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/h2943e/h2943e.pdf; Published 2001; Accessed 01.01.14.

- 12.Deng G. Integrative cancer care in a US academic cancer centre: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. Curr Oncol. 2008;15 doi: 10.3747/co.v15i0.276. s108.es68-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joos S., Musselmann B., Szecsenyi J. Integration of complementary and alternative medicine into family practices in Germany: results of a national survey. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2011;2011:495813. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keshet Y., Ben-Arye E. Which complementary and alternative medicine modalities are integrated within Israeli healthcare organizations and do they match the public's preferences? Harefuah. 2011;150:635–638. 689, 690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baer H. The emergence of integrative medicine in Australia: the growing interest of biomedicine and nursing in complementary medicine in a southern developed society. Med Anthropol Q. 2008;22:52–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2008.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi E., Baccetti S., Firenzuoli F., Belvedere K. Homeopathy and complementary medicine in Tuscany, Italy: integration in the public health system. Homeopathy. 2008;97:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fahimi F., Hrgovic I., El-Safadi S. Complementary and alternative medicine in obstetrics: a survey from Iran. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:361–364. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1641-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salkeld E.J. Integrative medicine and clinical practice: diagnosis and treatment strategies. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2008;13:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoff W. Traditional health practitioners as primary health care workers. Trop Dr. 1997;27:52–55. doi: 10.1177/00494755970270S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan A., Chen C.A. Integrating traditional practices into allopathic medicine. Glob Health J. 2012;2:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Summary of Infrastructure Facilities under AYUSH. Available at: http://indianmedicine.nic.in/showfile.asp?lid=44; Accessed 03.12.14.

- 22.State-wise Statistics of Homeopathy under AYUSH. Available at: http://indianmedicine.nic.in/writereaddata/linkimages/3833835927-West%20Bengal.pdf; Accessed 03.12.14.

- 23.Central Council for Research in Homeopathy, Dept. of AYUSH, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India. Available at: http://ccrhindia.org/Institute.asp; Accessed 03.12.14.

- 24.Report of the Steering Committee of AYUSH for 12th five year plan (2012-2017). Health Division Planning Commission, Govt. of India. Available at: http://planningcommission.gov.in/aboutus/committee/strgrp12/st_ayush0903.pdf; Accessed 03.12.14.

- 25.Singh B., Kumar M., Singh A. Evaluation of implementation status of national policy on Indian systems of medicine and homeopathy 2002: stakeholders' perspective. Anc Sci Life. 2013;33:103–108. doi: 10.4103/0257-7941.139048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh R.H. Mission mainstreaming of AYUSH void of strategies and action plans. Ann Ayur Med. 2013;2:56–57. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unnikrishnan P. Role of traditional medicine in primary health care: an overview of perspectives and challenges. Yokohama Int Soc Sci Res. 2010;14:57–77. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh B., Singh A., Kumar M. Unification of Indian systems of medicine and homoeopathy policy and national health policy in India – Stakeholders' perspective. Spatula DD. 2012;2:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross C.L. Integral healthcare: the benefits and challenges of integrating complementary and alternative medicine with a conventional healthcare practice. Integr Med Insights. 2009;4:13–20. doi: 10.4137/imi.s2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandhiok N., Joglekar N., Shrotri A., Choudhury P., Chaudhury N., Singh S. Task-shifting challenges for provision of skilled birth attendance: a qualitative exploration. Int Health. 2014 Aug 4 doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihu048. pii: ihu048. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]