Abstract

NF-κB plays an important role in many types of cancer, including prostate cancer (PCa), but the role of the upstream kinase of NF-κB, IKKβ, in PCa has not been fully documented, nor are there any effective IKKβ inhibitors used in clinical settings. Here, we have shown that IKKβ activity is mediated by multiple kinases including IKKα in human PCa cell lines that express activated IKKβ. Immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) of human PCa tissue microarrays (TMA) demonstrates that phosphorylation of IKKα/β within its activation loop gradually increases in low to higher stage tumors as compared to normal tissue. The expression of cell proliferation and survival markers (Ki67, Survivin), epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers (Slug, Snail), as well as cancer stem cell (CSC) related transcription factors (Nanog, Sox2, Oct-4), also increase in parallel among the respective TMA samples analyzed. IKKβ, but not NF-κB, is found to regulate Nanog, which, in turn, modulates the levels of Oct4, Sox2, Snail and Slug, indicating an essential role of IKKβ in regulating cancer stem cells and EMT. The novel IKKβ inhibitor CmpdA inhibits constitutively activated IKKβ/NF-κB signaling, leading to induction of apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation, migration and stemness in these cells. CmpdA also significantly inhibits tumor growth in xenografts without causing apparent in vivo toxicity. Furthermore, CmpdA and docetaxel act synergistically to inhibit proliferation of PCa cells. These results indicate that IKKβ plays a pivotal role in PCa, and targeting IKKβ, including in combination with docetaxel, may be a potentially useful strategy for treating advanced PCa.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, IKKβ, NF-κB, PTEN, Akt, mTORC1, IKKβ inhibitors, CmpdA

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer ranks as the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths among men in the Western world (1). The standard treatment for metastatic prostate cancer is androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), but while initially effective in inducing a clinical response, invariably fails within two years in most patients, resulting in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Several treatment options are currently available for CRPC patients, including second line hormonal therapy, a dendritic cell-based vaccine (sipuleucel-T), bone targeted agents (radium-223), and cytotoxins such as docetaxel and cabazitaxel. However, these treatments ultimately provide limited benefit due to the inability to provide a long-lasting response (2–5). Thus, to improve treatment outcomes, identification of relevant signaling pathways associated with the development of CRPC and resistance to cytotoxic agents remains a major challenge.

The PI3 Kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway plays a critical role in many physiological cellular processes as well as in cancer. Activated PI3K phosphorylates PtdIns(4,5)P2 to produce phosphoinositide PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 that, in turn, recruits PDK1 and Akt to the plasma membrane where Akt is phosphorylated and activated by PDK1. The tumor suppressor gene PTEN is a phosphatase that dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, thus decreasing Akt activity (6). Inactivation of PTEN mutations is common in cancer, resulting in constitutive activation of Akt. One of the major downstream substrates of Akt is TSC2, which is phosphorylated to activate the mammalian target of Rapamycin (mTOR), another important tumorigenesis-promoting kinase (7–10). PTEN mutations have been identified in over fifty percent of tumor samples from patients with CRPC. The cumulative evidence indicates that loss of PTEN function and subsequent activation of Akt and mTOR are critical events in the progression of human prostate cancer (11, 12).

The nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) family is comprised of 5 members: RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, p50/p105 (NF-κB1), and p52/p100 (NF-κB2). NF-κB signaling is activated by a variety of inflammatory mediators and growth factors through canonical and non-canonical pathways (13, 14). In most signaling cascades, NF-κB is activated by the canonical pathway that utilizes the IKK complex that contains IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ. IKKα and IKKβ drive the catalytic activity of IKK, with IKKβ playing a dominant role in inflammatory-mediated pathways. Normally, p50 and p65 NF-kB heterodimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm in an inactive state by IκBα. Upon stimulation, the IκB kinase (IKK) complex is activated, leading to IκBα phosphorylation, which results in ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of IκBα and subsequent p50 and p65 heterodimer translocation to the nucleus. Dysregulation of NF-κB activity is associated with numerous cancers (13, 15), and can induce gene expression to regulate different cellular processes, including cell proliferation, survival, invasion, metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy (13–16).

A number of studies have shown that NF-κB signaling plays a pivotal role in prostate cancer (17–19). Clinically, prostate cancer patients with elevated NF-κB have a worse prognosis. The extent of nuclear NF-κB p65 staining has been shown to correlate with tumor grade in prostate cancer (20). In addition, it has been reported that NF-κB signaling is upregulated in CRPC patients and correlates with disease progression (21–24). We previously shown that both mTORC1 and NF-κB activity are upregulated downstream of Akt in PTEN null prostate cancer cells, and mTORC1 interacts with the IKK complex to promote induction of NF-κB (25, 26). In the present study, we hypothesize that IKKβ, the upstream regulator of NF-κB, is an essential driver in PCa. We carried out both in vitro and in vivo studies to determine the role of IKKβ/NF-κB in regulating prostate cancer tumorigenesis. In addition, we evaluated the targeting of IKKβ by the novel IKKβ inhibitor CmpdA in prostate cancer cells expressing activated IKKβ. Our results suggest that IKKβ may be an important target in prostate cancer, particularly in the context of functional PTEN deficiency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemical reagents

The Akt inhibitor Perifosine (KRX-0401) was purchased from Selleck Chemical. Docetaxel was purchased from Cell Signaling. The IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, was kindly provided by Dr. Albert Baldwin, University of North Carolina. Antibodies against IKKα, IKKβ, and Akt were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology. Antibodies for immunohistochemistry (IHC), including Ki67, cleaved caspase-3, p-IKKα/β-S177/S181, Slug and Snail were from Abcam. HRP-labeled anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies for Oct4 (CST-2750), Sox2 (CST-3728), p65 (CST-8242), p-p65 (CST-3033), Survivin (CST-2808), p-Akt-S473 (CST-4058), GAPDH (CST-5174), as well as any additional antibodies were from Cell Signaling.

Cell lines and cell culture

Prostate cancer cell lines PC3 and Du145 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) in 2013, and no authentication was performed in the laboratory. All cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mmol glutamine, and 100 units/ml penicillin and streptomycin. All the cell lines were meticulously passaged and tested for Mycoplasma contamination.

Cell lysis and western blotting

Cells were grown in 100-mm dishes, rinsed twice with cold PBS, and then lysed on ice for 20 minutes in 1 ml of lysis buffer [40 mmol/liter HEPES (pH 7.5), 120 mmol/liter NaCl, 1 mmol EDTA, 10 mmol pyrophosphate, 10 mmol glycerophosphate, 50 mmol NaF, 0.5 mmol orthovanadate, and EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science)] containing 1% Triton X-100 or 0.3% CHAPS. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min, samples containing 20–50 μg protein/lane were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to Pure Nitrocellulose Membrane (Bio-Rad), blocked in 5% nonfat milk, and then blotted with the indicated antibodies.

RNA interference

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) SMARTpool Raptor, IKKα, IKKβ, NF-κB p65 and Nanog were from Dharmacon. Each represents four pooled SMART-selected siRNA duplexes that target the indicated genes. PC3 cells were transfected with SMARTpool IKKβ, p65 or nonspecific control siRNAs using DharmaFECT 1 reagent (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, a final concentration of 20 nmol of siRNA was used to transfect cells for 48–72 hours.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured by MTS assay using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous ONE Solution kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5×104 cells/ml for 24 hours, then the culture media was replaced with fresh media containing the indicated concentrations of CmpdA or vehicle control (DMSO). After incubation for an additional 48 hours, MTS reagent (20 μl) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 – 4 hours. Absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Three independent experiments were performed, each in triplicate.

Caspase-3/7 activity assay

Cells were plated in triplicate at 4 × 103 cells/per well in white-walled 96-well plates (Becton Dickinson). Cells were transfected with siRNA as described above and treated with the IKK inhibitor and/or docetaxel as indicated. Caspase-3/7 activity was measured at 48 hours post-transfection using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay uses a caspase-3/7 tetrapeptide DEVD substrate that produces a luminescent signal on cleavage. Relative light units were measured on an Lmax Microplate Luminometer (Molecular Devices).

Colony formation assays

One thousand cells were seeded into 6-well plates and incubated for 5 or 7 days after the appropriate treatment. The colonies were stained with crystal violet (0.5% w/v) and images taken using a scanner (Epson, USA).

Analysis of cell cycle and apoptosis via flow cytometry

Cell cycle analysis was performed as described previously (27). In brief, cells were fixed with 70% cold ethanol at 20 °C for at least 1.5 hours and stained with PBS containing 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) and 30 μg/ml RNase A, and the samples analyzed for DNA content and apoptotic cells (sub-G0/G1 fraction) via a flow cytometer (FACS Canto; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Cell migration assay

Scratch wound-healing assay was performed to determine cell migration using confluent cultures (80% – 90% confluence). Cells were photographed under a microscope at 0, 24 and 48 hours.

Real time cell migration assay

75,000 cells were plated in serum-free media in the upper chamber of a CIM plate after serum starvation for 18 hours and CmpdA (2 or 5 μM) or vehicle control were added simultaneously. The lower chamber was filled with either serum-free media (negative control) or full media (DMED with 10% FCS). Cells (with or without treatment) were allowed to equilibrate at room temperature for 1 hour and then incubated at 37 °C for 48 hours in an Xcelligence DP module.

Tumor xenograft study

The Translational Laboratory Shared Services (TLSS) at the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center performed the in vivo studies using eight-week-old male nu/nu mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley). 5 × 106 PC3 cells were mixed with 50 μL Matrigel and injected into the flanks of nude mice. Nine days after cell injection, mice were sorted into three balanced groups. CmpdA (10 or 15 mg/kg) or vehicle control (10% dimethyl sulfoxide in saline) was given intraperitoneally (IP) twice a week for three weeks. The growth of the tumors was measured with electronic calipers twice per week for 3 weeks. Tumor volumes were calculated using the equation Vol=(L×W2)/2 where L is the longer dimension and W is the shorter dimension. The tumors were then harvested for subsequent analysis.

Tissue microarray (TMA)

Prostate cancer tissue microarray arrays T191 and PR243B were obtained from US BioMax, Inc.

Immunohistochemical analysis

All immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses were conducted by the Pathology Core Facility at the Baltimore VA Medical Center.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to analyze the statistical significance of 3 or more groups. p-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

IKKβ activity is regulated by Akt, mTORC1 and IKKα in prostate cancer PC3 cells

Our previous studies showed that both mTORC1 and NF-κB activity were upregulated in AR negative PTEN null PC3 prostate cancer cells (25, 26). In these cells, the IKK complex associates with the mTORC1 complex downstream of Akt. Moreover, IKKα enhances mTORC1 activity, while mTORC1 promotes IKKα and IKKβ activity to upregulate NF-κB function in a positive feedback loop (25, 26). These findings suggested that IKKβ could be a downstream target of Akt, mTORC1 and IKKα in PC3 cells (Fig. S1A). To test this model, we first employed a pan Akt inhibitor, perifosine, that simultaneously blocks the activity of all three isoforms of Akt (28, 29). PC3 cells were treated with different concentrations of perifosine for 2 hours and phosphorylation of Akt, IKK (both IKKα and IKKβ), S6K (mTOR target), and IκBα and p65 (IKK substrates) was determined by Western blot. As shown in figure S1B, perifosine dramatically reduced Akt phosphorylation, as well as that of S6K, IKKα/β, IκBα and p65, confirming that both mTORC1 and IKK/NF-κB signaling pathways are downstream targets of Akt. We previously demonstrated that depletion of mTORC1 (by mTOR or Raptor knockdown) decreased the activity of both IKKα and IKKβ (26), suggesting that mTORC1 regulates IKKα and IKKβ downstream of Akt (Fig. S1A). Decreased phosphorylation of S6K, p65 and IκBα occurred after knockdown of IKKα (Fig. S1D). Importantly, phosphorylation of IKKβ was also dramatically reduced in a dose-dependent manner upon IKKα knockdown (Fig. S1C). Taken together, these results suggest that IKKα can affect IKKβ through mTORC1-dependent and independent mechanisms (Fig. S1A and S1C). In addition, knockdown of IKKβ impairs the phosphorylation of both IKKα and p65, yet has no significant effects on S6K phosphorylation. Thus, IKKβ appears to activate NF-κB downstream of IKKα and mTORC1, and is, itself, activated by Akt, mTORC1 and IKKα in PC3 cells (Fig. S1A and S1D).

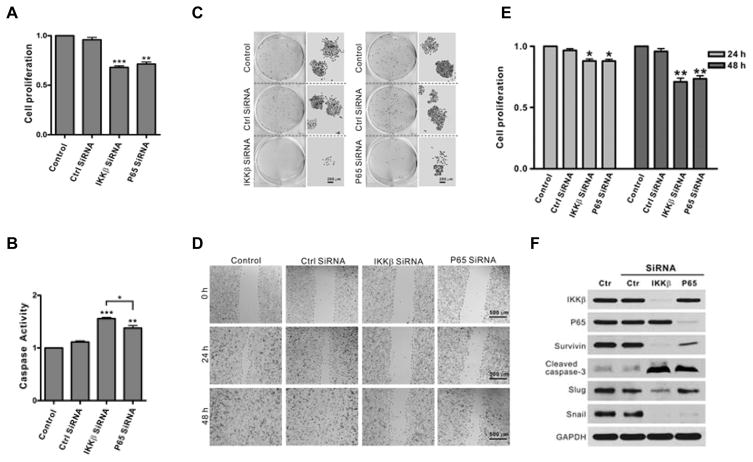

Depletion of IKKβ/NF-κB signaling inhibits cell proliferation and migration and leads to apoptosis in PC3 cells

To determine whether the IKKβ/NF-κB pathway plays a role in tumorigenesis, we evaluated the effects of IKKβ and NF-κB knockdown on cell proliferation, survival and migration. The results showed that knockdown of either IKKβ or p65 leads to inhibition of cell proliferation, with a greater reduction in cell proliferation observed after IKKβ knockdown, as compared to p65 (Fig. 1A). Reduction in IKKβ or p65 expression caused a dramatic increase in apoptosis as well as a significant decrease in PC3 cell colony formation, with greater effects on these parameters noted with IKKβ knockdown (Fig 1B and 1C). PC3 cell migration was also strongly suppressed after either IKKβ or p65 knockdown (Fig. 1D) in line with the decrease of cell proliferation (Fig. 1E). Consistent with the role of IKKβ/p65 signaling in cell survival, Western blot analysis revealed that knockdown of either IKKβ or p65 resulted in decreased expression of Survivin and enhanced cleavage of caspase-3 (Fig. 1E). Interestingly, EMT markers were differentially affected by IKKβ and p65. IKKβ knockdown dramatically reduced the expression of both Slug and Snail, whereas knockdown of p65 decreased only Snail expression (Fig. 1E). Taken together, the above studies demonstrate that IKKβ and p65 are important in regulating key biological properties of PC3 cells, with IKKβ, in particular, playing a more prominent role in these processes.

Figure 1. Knockdown of IKKβ impairs cell proliferation, survival and migration.

A. PC3 cells were transfected with control, IKKβ or p65 siRNA for 72 hours and cell proliferation was determined by MTT assay. The experiments were repeated three times in triplicate (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). B. Cells were treated as described in Fig. 1A for 72 hours and caspase activity was measured. The experiments were repeated three times in triplicate (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). C. Cells were transfected with control, IKKβ or p65 siRNA for 24 hours followed by seeding of 1000 cells in 6-well plates, then incubation for 5 days, followed by colony staining. D. Cells were transfected with control, IKKβ or p65 siRNA for 48 hours. Scratches were made on cell monolayers and wound closure was monitored at 0, 24 and 48 hours. The experiments were repeated three times. E. Cells were transfected with control, IKKβ or p65 siRNA for 48 hours prior to planted in 96 well plates and cell proliferation was determined by MTT assay at 0, 24 and 48 hours. F. Cells were transfected with control, IKKβ or p65 siRNA for 72 hours and the expressions of IKKβ, p65, Survivin, cleaved caspase-3, Slug and Snail were determined by Western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times.

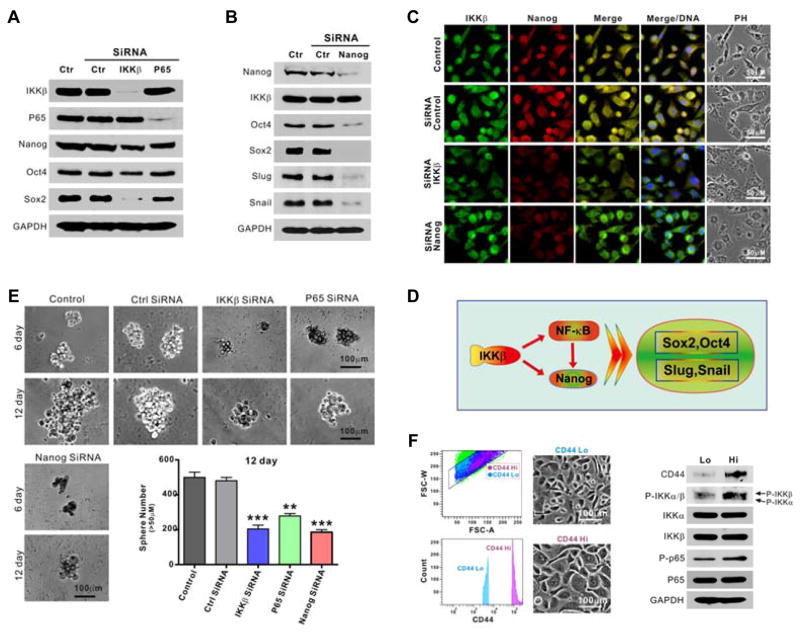

Knock down of IKKβ/NF-κB inhibits stemness in PC3 cells

To determine whether the IKKβ/NF-κB pathway plays a role in modulating stemness in prostate cancer cells, the expression patterns of the transcription factors Nanog, Oct-4 and Sox2 were examined after knockdown of IKKβ or p65 NF-κB. Knockdown of IKKβ decreased Nanog, Oct-4 and Sox2 levels, whereas knockdown of NF-κB caused only minimal reduction of Sox2 and had no effects on Oct4 and Nanog expression (Fig. 2A). Previous reports showed that Nanog is upstream of Oct-4 and Sox2 (30, 31), as well as Snail and Slug. Knockdown of Nanog decreased the levels of Oct-4, Sox2, Snail and Slug in PC3 cells but had no effect on IKKβ expression (Fig. 2B). Similar results were observed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2C). Thus, IKKβ, in particular, appears to be relevant in the regulation of several modulators of EMT, primarily in a NF-κB-independent manner (Fig. 2D). Further, knockdown of IKKβ or NF-κB can significantly impair the ability of PC3 cells to form tumor spheres (Fig. 2E). Moreover, when PC3 cells are sorted into CD44hi and CD44lo sub-populations, the enhanced phosphorylation of IKK and NF-κB in the former sub-population further suggests that IKKβ/NF-κB signaling is associated with a cancer stem-like cell (CSLC) phenotype (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2. Knockdown of IKKβ inhibits stemness via Nanog, Oct-4 and Sox2 in PC3 cells.

A. Cells were transfected with control, IKKβ or p65 siRNA for 72 hours and the expressions of IKKβ, p65, Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 were determined by Western blot. GAPDH was used for a loading control. B. Cells were transfected with control or Nanog siRNA for 72 hours and the expressions of IKKβ, Nanog, Oct4, Sox2, Snail and Slug were determined by Western blot. GAPDH was used for a loading control. C. Cells were transfected with control, IKKβ or Nanog siRNA for 72 hours and the expressions of IKKβ and Nanog determined by immunofluorescence (IF). D. Proposed model of IKKβ regulation of CSC and EMT through NF-κB-dependent and independent mechanisms. E. Cells were transfected with control, IKKβ, p65 or Nanog siRNA, and tumor sphere formation was monitored and counted (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). F. Cells were sorted via flow cytometry using CD44 antibody, cultured and then analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies.

IKK phosphorylation is consistent with expression of EMT- and CSC-related proteins in prostate cancer patients

Next, tissue microarrays derived from patient tumor samples were examined via immunohistochemistry (IHC). Phosphorylation of IKKα/β and the expressions of Ki67 and Survivin gradually increased from normal tissue to T2N0M0 to T3N0M1 to T4N1M1 tumors, suggesting that increased IKK activity is associated with higher clinical stages of prostate cancer (Fig S2, left panel). Further, the expressions of Snail and Slug, as well as Nanog, Oct-4 and Sox2 also increased in parallel from normal tissue to low and higher stage tumors (Fig S2, right panel), suggesting that IKKβ and related downstream signaling may be particularly relevant in the more advanced stages of prostate cancer.

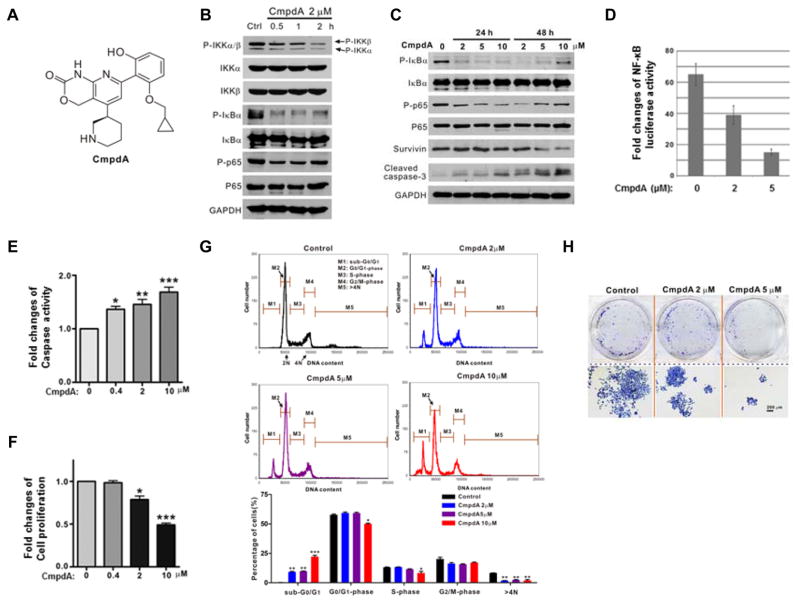

Effects of the novel IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, on PC3 and DU145 cells

CmpdA is a novel selective low-molecular-weight inhibitor of IKKβ (Fig. 3A and ref. 32). Treatment of PC3 cells with 2 μM CmpdA for 0.5 – 2 hours results in prominent inhibition of phosphorylation of IKKβ without any effects on IKKα phosphorylation. Consistently, IκBα and p65 phosphorylation deceased upon CmpdA treatment (Fig. 3B). CmpdA caused rapid and complete inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation, whereas the dynamics of p65 inhibition were more protracted with maximal inhibition of the latter occurring at 24 hours (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, some resurgence in IκBα and p65 phosphorylation 48 hours after treatment may in part be due to the short half-life of CmpdA and/or reflect an escape mechanism (Fig. 3C). Further, the expression of Survivin is suppressed upon 48 hours CmpdA treatment (Fig. 3C). CmpdA also induced caspase-3 cleavage in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). In addition, CmpdA suppresses NF-κB promoter-reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D). In terms of potential anti-cancer effects, CmpdA induces cellular caspase 3/7 activity (Fig. 3E) and inhibits cell proliferation (Fig. 3F). A dose-dependent increase in the sub-G0/G1 peak on flow cytometry corroborates the pro-apoptotic effects of CmpdA on PC3 cells (Fig. 3G). In addition, at higher concentrations, CmpdA significantly prevents PC3 cells from entering the S phase, and also gradually decreases the percentage of cells with DNA content > 4N (Fig. 3G), suggesting that it inhibits G1/S transition and mitosis in PC3 cells. Consistent with its anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic properties CpmdA inhibits colony http://www.iciba.com/formation/formation of PC3 cells (Fig. 3H).

Figure 3. CmpdA inhibits IKKβ/NF-κB signaling, cell proliferation and survival in PC3 cells.

A. Molecular structure of CmpdA (ref. 32). B. PC3 cells were treated with vehicle control or CmpdA (2 μM) for 0.5 – 2 hours and phosphorylation status of IKKα/β, IκBα and p65 was analyzed by Western blot. C. PC3 cells were treated with vehicle control or CmpdA (2 to 10 μM) for 0.5 – 48 hours and phosphorylation status of IκBα and p65 and levels of Survivin and cleaved caspase 3 were analyzed by Western blot. D. PC3 cells were transfected with NF-κB reporter and Renilla reporter control for 24 hours and treated with CmpdA for an additional 24 hours. Cells were harvested and an NF-κB reporter assay was performed. The experiments were repeated three times. E. Cells were treated with CmpdA for 48 hours and cell apoptosis was determined by measuring caspase activity. The results are representative of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). F. Cells were treated with CmpdA for 48 hours and cell proliferation was determined by MTT assay. The results are representative of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). G. Apoptosis was determined via flow cytometry. PC3 cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of CmpdA (2, 5, and 10 μM) for 72 hours. Cells were collected and washed twice with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 70% cold ethanol at 20 °C for 1.5 hours and stained with 1XPBS containing 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) and 30 μg/ml RNase A, and the samples were analyzed for DNA content and apoptotic cells via fow cytometry. H. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates, incubated with CmpdA for 7 days and then stained for colony formation. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

We extended the above studies to another AR-negative prostate cancer cell line, DU145, that also possesses high basal levels of NF-κB activity but has wild type PTEN (33). DU145 cells have high levels of phosphorylated p65 and IκBα, suggesting that IKK is constitutively active in these cells (Fig. S3A). We evaluated the anti-tumor activity of CmpdA in DU145 cells. Phosphorylation of both NF-κB and IκBα were inhibited by CmpdA in a dose-and time-dependent manner (Fig. S3A and S3B). Similar to PC3 cells, CmpdA dramatically inhibited DU145 cell proliferation, increased cellular caspase 3/7 activity, decreased colony formation, induced cell apoptosis, suppressed expression of Survivin, and increased expression of cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. S3C–S3H).

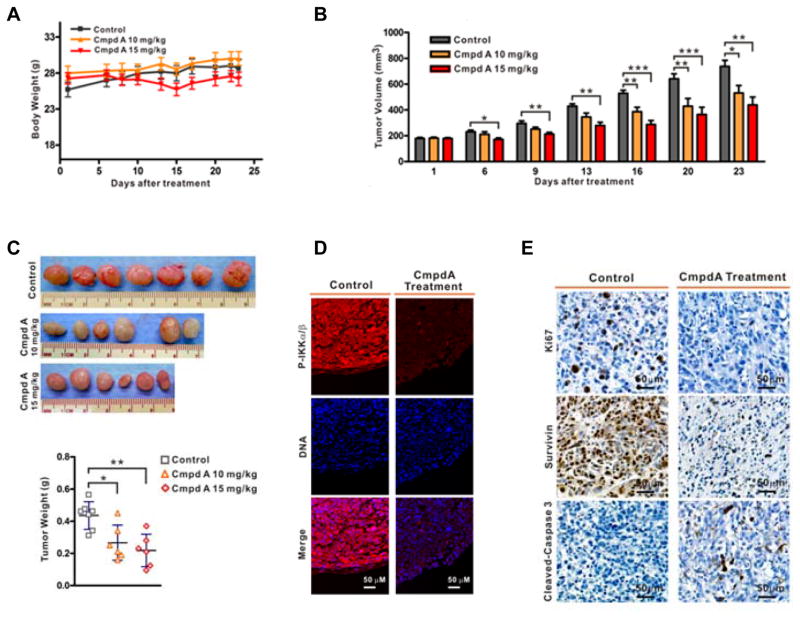

CmpdA suppresses tumorigenesis in vivo

A recent study demonstrated that CmpdA (10 mg/kg) inhibited K-Ras induced lung tumors in a mouse model (34). We evaluated the tolerability and anti-tumor activity of CmpdA in vivo using mouse xenografts. When tumors reached approximately 200 mm3 after PC3 cell inoculations, mice were randomized to one of three treatment groups: vehicle control (n = 7), 10 kg/mg (n = 6) or 15 kg/mg CmpdA (n = 6). The mice were treated via intraperitoneal injection (IP) twice a week for three weeks. Both doses of CmpdA were tolerable as shown by the lack of weight loss among the treated mice for the duration of the study (Fig. 4A). As a single agent, CmpdA has modest but consistent inhibitory effects on PC3 tumor growth in vivo, as determined by relative tumor volume and tumor weight measurements (Fig. 4B, 4C). Immunofluorescence assays demonstrated that CmpdA inhibited phosphorylation of IKK in the xenograft tumors (Fig. 4D). Further, IHC staining revealed that Ki67 and Survivin expression were reduced dramatically while cleaved caspase 3 was increased in tumors from CmpdA-treated mice compared to tumors from vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these data are consistent with the notion that inhibition of IKKβ can lead to anti-tumor effects in an in vivo model of prostate cancer.

Figure 4. CmpdA suppresses xenograft tumor formation and induces apoptosis in tumors.

A. Mice inoculated with PC3 cells were treated with different doses of CmpdA. Mouse body weights were monitored twice per week for three weeks (left) and final body weights were determined at the time of sacrifice (right). B. Tumor growth curves based on tumor volumes measured twice weekly (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). C. Tumors were photographed and weights recorded at the time of sacrifice (*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01). D. Xenograft tumors harvested from vehicle- or CmpdA-treated mice were stained with p-IKKα/β. E. Xenograft tumors harvested from vehicle- or CmpdA-treated mice were stained with Ki67, Survivin, or cleaved caspase-3 antibodies, and representative images are shown.

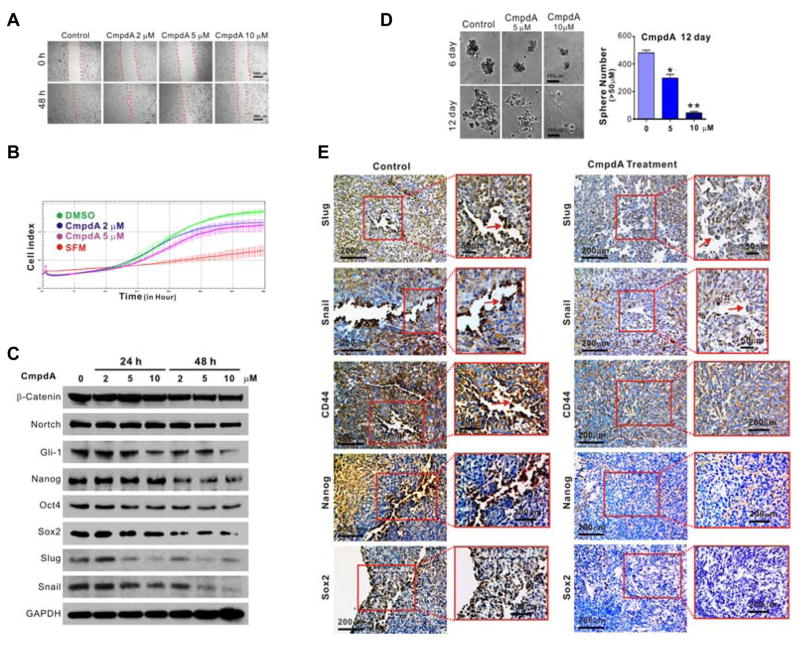

Inhibition of IKKβ/Nanog signaling as well as EMT, migration and stemness by CmpdA

CmpdA impaired cell migration in a dose-dependent manner in a wound-healing assay (Fig. 5A). Similarly, it inhibited PC3 cell migration in the xCELLigence real time cell system as noted by a change in the cell index over time (Fig 5B). Similar effects of CmpdA on the migratory characteristics were observed in DU145 cells (Fig. S4A–S4C). CmpdA also inhibits PC3 cell tumor sphere formation (Fig. 5C), and the expression of EMT markers including Snail and Slug, as well as transcription factors Nanog, Oct-4 and Sox2 (Fig. 5D). The expressions of other cancer stem cell-related genes were also detected. CmpdA decreased expression of Gli-1 while having no effect on β-catenin or Notch. Meanwhile, the expression of Snail, Slug, Nanog, Sox2 and CD44 were observed in control groups of xenograft tumors especially on the margin of the tumors and were significantly decreased in CmpdA treated tumors (Fig 5E).

Figure 5. Suppression of cell migration and stemness by CmpdA.

A. Cells were treated with vehicle control or CmpdA, and scratches were made on cell monolayers. Wound closure was monitored at 0 and 48 h. The experiments were repeated three times. B. Cells were treated with vehicle control or CmpdA and migration was monitored using the xCELLigence System real-time cell analyzer instrument. C. Cells were treated with CmpdA and tumor sphere formation was monitored; representative images are shown (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). D. Cells were treated with different doses of CmpdA (0–48 hours), lysed and analyzed by Western blot. The results are representative of three independent experiments. E. Xenograft tumors harvested from vehicle- or CmpdA-treated mice were stained with Slug, Snail, Oct-4, Nanog and Sox2 antibodies, and representative images are shown.

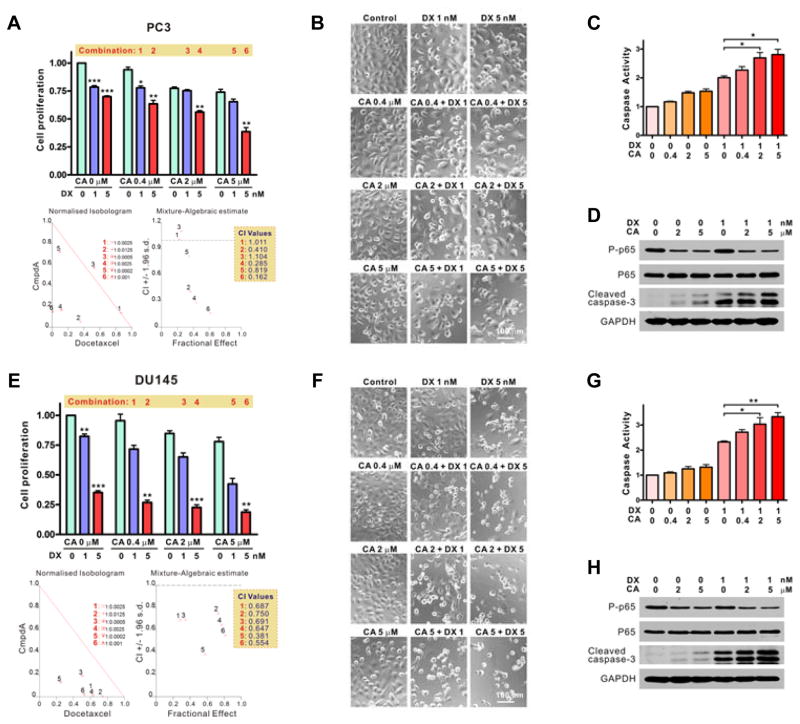

CmpdA synergizes with Docetaxel to induce apoptosis in PC3 and DU145 cells

The above series of studies demonstrate that CmpdA as single agent has significant anti-tumor activity in prostate cancer cells that have constitutive IKKβ activation. Docetaxel is an FDA-approved chemotherapy drug used to treat recurrent or metastatic castration-resistant PCa, however, its efficacy is very limited in patients due to acquired resistance (4, 5). It is important to improve the efficacy of Docetaxel by combining it with other single- or multiple-pathway inhibitors. We wanted to determine whether enhanced anti-tumor inhibition could occur by dual targeting of IKKβ and the micro-tubular network through a combination of CmpdA and Docetaxel. Using the combination index (CI) method of Chou and Talalay (35, 36), we tested the effects of CmpdA and Docetaxel combinations on PC3 and DU145 cells. The CI values were determined using the CalcuSyn v2.0 software that provides quantitative definition for additive (CI = 1), synergistic (CI < 1), and antagonistic (CI > 1) effects of drug combinations (35, 36). The CI values were less than 1 with the CmpdA/Docetaxel combination with respect to both PC3 and DU145 cells (Fig. 6A and 6E), indicating synergistic anti-proliferative effects when the two agents were combined. CmpdA in combination with Docetaxel also induced caspase activation and caspase-3 cleavage in a dose-dependent manner in both PC3 (Fig. 6B–6D) and DU145 cells (Fig. 6F–6H). Thus, the combination of CmpdA and Docetaxel has strong synergistic anti-proliferative activity and induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells.

Figure 6. Studies with Docetaxel and CmpdA combinations.

A and E. PC3 (A) and DU145 (E) cells were treated with vehicle control, CmpdA (CA), Docetaxel (DX), or a combination of the two, and cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assay. Also shown are the calculated combination index (CI) values (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). B and F. PC3 (B) and DU145 (F) cells were treated as in A and E for 48 hours and cell morphology was assessed. C and G. PC3 (C) and DU145 (G) cells were treated as in A and E for 48 hours and caspase activity was measured (*, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01). D and H. PC3 (D) and DU145 (H) cells were treated as in A and E for 48 hours and phosphorylation status of p65 as well as cleavage of caspase-3 were determined by Western blot. The experiments were repeated three times.

DISCUSSION

Activation of Akt can lead to recruitment of downstream pathways that are important in modulating proliferative, anabolic and anti-apoptotic programs in cancer cells (6). Considerable efforts are being made to target Akt for the treatment of cancer. However, to date, strategies to target Akt as an anti-cancer therapy have met limited success due to toxicity and recruitment of compensatory mechanisms (29, 37, 38). One of the critical downstream targets of Akt is mTORC1, which plays an important role in controlling Akt-induced oncogenic events (6). However, mTOR inhibitors, such as rapamycin, and their derivatives show modest benefits in prostate cancer (39, 40). Hence, identification of other targetable oncogenic pathways that are turned on by loss of PTEN and activation of Akt and mTOR in prostate cancer is important to for their potential therapeutic effects in this disease.

NF-κB and its upstream kinase IKKβ are upregulated in prostate cancer, especially in a metastatic setting (17, 21, 23, 24). We previously reported that IKK/NF-κB signaling is activated by Akt and mTOR in PC3 prostate cancer cells, which suggests that IKK/NF-κB is an important downstream target of the Akt/mTORC1 signaling cascade (25, 26). In the present study, we studied the more detailed regulatory mechanisms whereby IKK/NF-κB is activated downstream of Akt in prostate cancer cells. We now demonstrate that IKKβ, the direct kinase of NF-κB, is activated not only by Akt and mTORC1, but also by IKKα. It should be noted that IKKα regulation of IKKβ may involve mTORC1 dependent and/or independent mechanisms; the latter may be particularly relevant in prostate cancer cells such as DU145 that have wild type PTEN and hence, unlike PC3 cells, do not have constitutive activation of Akt/mTOR (Fig. 1A). Regardless of the upstream pathways that may lead to IKKβ activation, our studies demonstrate that knockdown of IKKβ inhibits proliferation and migration, and induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Mechanistically, knockdown of IKKβ or NF-κB decreases the expression of Survivin, an important anti-apoptotic protein and NF-κB target gene, and induces caspase-3 cleavage.

Increasing evidence implicates cancer stem-like cells (CSC) in cancer initiation and growth, and resistance to anti-cancer therapy. Wnt, β-catenin and Notch, as well as certain embryonic stem cell self-renewal genes such as NANOG, Oct-4 and Sox2, among others, have been shown to play important roles in regulation of some of the biological properties of CSC. Elevated Nanog is associated with poorer outcomes in several cancers (11, 30, 31, 41–42). Depletion of Nanog results in decreased expressions of Sox2, Oct-4, Snail and Slug, and impairs the CSC and EMT phenotypes (38). For the first time, our data show that IKKβ regulates Nanog, as well as Sox2, Oct-4, Snail and Slug, most likely via NF-κB-independent mechanisms. Thus, IKKβ may be important in regulating CSC and EMT in some forms of prostate cancer.

It should also be noted that compared to knockdown of p65, knockdown of IKKβ causes increased induction of apoptosis (Fig. 1B), decreased protein levels of Slug (Fig. 1E), Nanog, Oct-4 and Nanog (Fig. 2A), and more impairments of tumor sphere formation (Fig. 2E). These data indicate that IKKβ modulates the malignance of PCa most likely through NF-κB-dependent and independent mechanisms, thus demonstrating its potential as a critical therapeutic target in PCa.

Several IKKβ inhibitors have been explored as potential therapeutics in recent years. However, to date, no IKKβ inhibitor has been successfully developed for clinical use, mainly due to toxicity (43–48). Thus, there remains a significant need to identify novel IKKβ inhibitors that can be safely exploited clinically. The novel IKKβ specific inhibitor CmpdA is a competitive ATP inhibitor that downregulates IKKβ activity and inhibits IκBα phosphorylation. CmpdA has been shown to suppress cell proliferation and sensitize several cancer cell lines to chemotherapy in vitro (49). A recent study showed that CmpdA effectively inhibited K-ras induced lung cancer in vitro and in vivo (34). To our knowledge, this agent has not yet been evaluated in prostate cancer. In the present study, we evaluated the anti-cancer activity of CmpdA in vitro and in vivo in two prostate cancer cell lines that have activated IKKβ. CmpdA led to significant inhibition of cell proliferation, cell migration and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and was associated with enhanced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Furthermore, CmpdA significantly inhibited the expression of transcription factors Nanog, Sox-2 and Oct-4 in both prostate cancer cells in cell culture and xenograft tumors, suggesting its potential in suppression of prostate cancer stemness. Importantly, CmpdA, as single agent, caused inhibition of tumor xenografts without significant loss of mouse body weight, suggesting that it may be associated with reduced toxicity in vivo. Given that targeting a single activated pathway is unlikely to provide meaningful long-term tumor control in a complex disease state such as prostate cancer, we also evaluated the effects of combining Docetaxel chemotherapy with CmpdA. That significant synergism exists between Docetaxel and CmpdA in inhibiting prostate cancer cells suggests that Docetaxel, in combination with IKKβ targeting, may be a viable strategy to explore further in future studies.

In summary, we demonstrate that activated IKKβ may represent a useful target, thus providing a rationale for exploring the therapeutic effects of novel IKKβ inhibitors with favorable toxicity profiles, particularly in the subgroups of advanced prostate cancer patients in whom such pathways may be activated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding support: This publication was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R00CA149178 and startup funds from Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Cancer Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine (H.C. Dan) and a Merit Review Award, Dept of Veterans Affairs (A. Hussain)

We thank Dr. Albert Baldwin in University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for providing the IKKβ inhibitor CmpdA.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Sawyers CL, Scher HI. Targeting the androgen receptor pathway in prostate cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan CJ, Tindall DJ. Androgen receptor rediscovered: the new biology and targeting the androgen receptor therapeutically. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3651–58. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khemlina G, Ikeda S, Kurzrock R. Molecular landscape of prostate cancer: Implications for current clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:761–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford ED, Higano CS, Shore ND, Hussain M, Petrylak DP. Treating Patients with Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of Available Therapies. J Urol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.06.106. S0022-5347:04423-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer cell. 2003;4:257–62. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manning BD, Cantley LC. United at last: the tuberous sclerosis complex gene products connect the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:573–78. doi: 10.1042/bst0310573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. Regulation of mTORC1 and its impact on gene expression at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:1713–19. doi: 10.1242/jcs.125773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoki K, Guan KL. Tuberous sclerosis complex, implication from a rare genetic disease to common cancer treatment. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R94–100. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–57. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: new prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1967–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.1965810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majumder PK, Sellers WR. Akt-regulated pathways in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:7465–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–88. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HJ, Hawke N, Baldwin AS. NF-kappaB and IKK as therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:738–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sizemore N, Lerner N, Dombrowski N, Sakurai H, Stark GR. Distinct roles of the Ikappa B kinase alpha and beta subunits in liberating nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappa B) from Ikappa B and in phosphorylating the p65 subunit of NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3863–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nadiminty N, Gao AC. Mechanisms of persistent activation of the androgen receptor in CRPC: recent advances and future perspectives. World J Urol. 2012;30:287–95. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0771-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin R, Yi Y, Yull FE, Blackwell TS, Clark PE, Koyama T, et al. NF-kappaB gene signature predicts prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2763–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin RJ, Lho Y, Connelly L, Wang Y, Yu X, Saint Jean L, et al. The nuclear factor-kappaB pathway controls the progression of prostate cancer to androgen-independent growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6762–69. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suh J, Payvandi F, Edelstein LC, Amenta PS, Zong WX, Gelinas C, et al. Mechanisms of constitutive NF-kappaB activation in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2002;52:183–200. doi: 10.1002/pros.10082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCall P, Bennett L, Ahmad I, Mackenzie LM, Forbes IW, Leung HY, et al. NFkappaB signalling is upregulated in a subset of castrate-resistant prostate cancer patients and correlates with disease progression. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1554–63. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen DP, Li J, Yadav SS, Tewari AK. Recent insights into NF-kappaB signalling pathways and the link between inflammation and prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2014;114:168–76. doi: 10.1111/bju.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shukla S, MacLennan GT, Fu P, Patel J, Marengo SR, Resnick MI, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB/p65 (Rel A) is constitutively activated in human prostate adenocarcinoma and correlates with disease progression. Neoplasia. 2004;6:390–400. doi: 10.1593/neo.04112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain G, Cronauer MV, Schrader M, Moller P, Marienfeld RB. NF-kappaB signaling in prostate cancer: a promising therapeutic target? World J Urol. 2012;30:303–10. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0792-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dan HC, Adli M, Baldwin AS. Regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin activity in PTEN-inactive prostate cancer cells by I kappa B kinase alpha. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6263–69. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dan HC, Cooper MJ, Cogswell PC, Duncan JA, Ting JP, Baldwin AS. Akt-dependent regulation of NF-{kappa}B is controlled by mTOR and Raptor in association with IKK. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1490–500. doi: 10.1101/gad.1662308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang YT, Ouyang DY, Xu LH, Ji YH, Zha QB, Cai JY, et al. Cucurbitacin B induces rapid depletion of the G-actin pool through reactive oxygen species-dependent actin aggregation in melanoma cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2011;43:556–67. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondapaka SB, Singh SS, Dasmahapatra GP, Sausville EA, Roy KK. Perifosine, a novel alkylphospholipid, inhibits protein kinase B activation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1093–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson EC, Evans CP, Mack PC, Devere-White RW, Lara PN., Jr Inhibition of Akt pathways in the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10:331–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santaliz-Ruiz LE, Iv, Xie X, Old M, Teknos TN, Pan Q. Emerging role of nanog in tumorigenesis and cancer stem cells. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2741–48. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noh KH, Kim BW, Song KH, Cho H, Lee YH, Kim JH, et al. Nanog signaling in cancer promotes stem-like phenotype and immune evasion. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4077–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI64057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegelbauer K, Gantner F, Lukacs NW, Berlin A, Fuchikami K, Niki T, et al. A selective novel low-molecular-weight inhibitor of IkappaB kinase-beta (IKK-beta) prevents pulmonary inflammation and shows broad anti-inflammatory activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:178–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gasparian AV, Yao YJ, Kowalczyk D, Lyakh LA, Karseladze A, Slaga TJ, et al. The role of IKK in constitutive activation of NF-kappaB transcription factor in prostate carcinoma cells. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:141–51. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basseres DS, Ebbs A, Cogswell PC, Baldwin AS. IKK is a therapeutic target in KRAS-Induced lung cancer with disrupted p53 activity. Genes Cancer. 2014;5:41–55. doi: 10.18632/genesandcancer.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70:440–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashton JC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method--letter. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freudlsperger C, Burnett JR, Friedman JA, Kannabiran VR, Chen Z, Van Waes C. EGFR-PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: attractive targets for molecular-oriented therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15:63–74. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.541440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Argiris A, Cohen E, Karrison T, Esparaz B, Mauer A, Ansari R, et al. A phase II trial of perifosine, an oral alkylphospholipid, in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:766–70. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majumder PK, Febbo PG, Bikoff R, Berger R, Xue Q, McMahon LM, et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bitting RL, Armstrong AJ. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:R83–99. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeter CR, Liu B, Liu X, Chen X, Liu C, Calhoun-Davis T, et al. NANOG promotes cancer stem cell characteristics and prostate cancer resistance to androgen deprivation. Oncogene. 2011;30:3833–45. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X, Rycaj K, Liu X, Tang DG. New insights into prostate cancer stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:579–86. doi: 10.4161/cc.23721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu F, Xia Y, Parker AS, Verma IM. IKK biology. Immunol Rev. 2012;246(1):239–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gamble C, McIntosh K, Scott R, Ho KH, Plevin R, Paul A. Inhibitory kappa B Kinases as targets for pharmacological regulation. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:802–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki J, Ogawa M, Muto S, Itai A, Isobe M, Hirata Y, et al. Novel IkB kinase inhibitors for treatment of nuclear factor-kB-related diseases. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20:395–405. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.559162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gasparian AV, Yao YJ, Lu J, Yemelyanov AY, Lyakh LA, Slaga TJ, et al. Selenium compounds inhibit I kappa B kinase (IKK) and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kappa B) in prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:1079–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yemelyanov A, Gasparian A, Lindholm P, Dang L, Pierce JW, Kisseljov F, et al. Effects of IKK inhibitor PS1145 on NF-kappaB function, proliferation, apoptosis and invasion activity in prostate carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:387–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gasparian AV, Guryanova OA, Chebotaev DV, Shishkin AA, Yemelyanov AY, Budunova IV. Targeting transcription factor NFkappaB: comparative analysis of proteasome and IKK inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1559–66. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.10.8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bednarski BK, Baldwin AS, Jr, Kim HJ. Addressing reported pro-apoptotic functions of NF-kappaB: targeted inhibition of canonical NF-kappaB enhances the apoptotic effects of doxorubicin. PloS one. 2009;4:e6992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.