Abstract

The average retail price per pack of cigarettes is less than $6, which is substantially lower than the $10 per-pack target established in 2014 by the Surgeon General to reduce the smoking rate. We estimated the impact of three cigarette pricing scenarios on smoking prevalence among teens aged 12–17 years, young adults aged 18–25 years, and adults aged ≥26 years, by state: (1) $0.94 federal tax increase on cigarettes, as proposed in the fiscal year 2017 President's budget; (2) $10 per-pack retail price, allowing discounts; and (3) $10 per-pack retail price, eliminating discounts. We conducted Monte Carlo simulations to generate point estimates of reductions in cigarette smoking prevalence by state. We found that each price scenario would substantially reduce cigarette smoking prevalence. A $10 per-pack retail price eliminating discounts could result in 637,270 fewer smokers aged 12–17 years; 4,186,954 fewer smokers aged 18–25 years; and 7,722,460 fewer smokers aged ≥26 years. Raising cigarette prices and eliminating discounts could substantially reduce cigarette smoking prevalence as well as smoking-related death and disease.

Tobacco price increases discourage smoking initiation among young people, prompt quit attempts, and reduce consumption.1–4 According to a 2012 report by the Surgeon General, teens and young adults who are transitioning from relying on peers for cigarettes to buying their own—and who are, therefore, at greatest risk of becoming established smokers—are significantly more price-sensitive than adults.2

The 2014 Surgeon General's report on the health consequences of smoking outlined evidence-based actions to reduce the smoking rate to <10% within 10 years. Raising cigarette excise taxes was a key recommendation to prevent smoking initiation among young people and encourage cessation, with an initial target of $10 per-pack or higher average retail price.1 Federal, state, and local taxes can be combined to achieve this target. However, as of November 2014, the average retail price per pack of cigarettes in the United States was $5.84, ranging from a low of $4.38 in Missouri to a high of $10.03 in New York State.5 Primary drivers of this price differential are state tobacco excise taxes, which range from $0.17 per pack in Missouri to $4.35 per pack in New York State.5 The fiscal year 2017 President's budget proposes a $0.94 per-pack excise tax increase on cigarettes and small cigars; at the federal level, no tobacco excise tax has been enacted since a 2009 increase from $0.39 to $1.01 per pack.6

Tobacco industry promotions, including direct mail, Internet, and point-of-sale coupons; buy-one-get-one-free offers; and multipack discounts, undermine local, state, and federal pricing policies.2 To maintain higher prices on tobacco products, some localities now prohibit the redemption of coupons and multipack discounts at retail.7

We examined the potential effects of (1) a $0.94 per-pack federal tax on cigarettes; (2) a $10 per-pack average retail price, allowing discounts; and (3) a $10 per-pack average retail price, eliminating discounts, on cigarette smoking among youth, young adults, and adults, nationally and by state. To date, no study has modeled the impact of the three selected cigarette price scenarios on smoking prevalence. Assessing the potential impact of tobacco price policies on smoking prevalence can inform public health policy, planning, and prioritization.

METHODS

This study used state cigarette smoking prevalence estimates among youth aged 12–17 years, young adults aged 18–25 years, and adults aged $26 years from the 2012/2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.8 We obtained state cigarette prices from the 2010–2011 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS), which captures self-reported data on average prices paid per pack, including consumer-targeted discounts.9 We obtained the measure of price-related discounts from an existing analysis that estimated per-pack price reductions associated with price promotions after controlling for other price minimization strategies.10 We adjusted self-reported cigarette prices to 2013 U.S. dollars using the Consumer Price Index.11 We obtained state populations, by age, from the U.S. Census Bureau12 and short-run price elasticity estimates for youth, young adult, and adult smokers from a literature review by the Community Preventive Services Task Force, which included studies that controlled for general time trend or year fixed effects.13

In May 2015, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations to generate estimates using Stata® version 14.0.14 The simulation used uniform distributions for model inputs, including smoking prevalence, price elasticity, and discounts, to generate random outcomes for reductions in smoking prevalence and number of smokers. We calculated point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (available from the authors) overall and by state.

We conducted the simulation according to the following specification:

where the change in smoking prevalence among age group i, in state j, under the scenario t (ChangeSPijt) is a function of current smoking prevalence of age group i, in state j (CurrentSPij); the price elasticity of the age group (PriceElasticityi); the price difference in state j, under the scenario t (PriceDiffjt); and the average per-pack price paid in state j (PricePaidperpackj). The price differences varied by simulated scenarios. In the first scenario, the retail per-pack price was assumed to be increased by $0.94. In the second scenario, the price was assumed to be increased by the difference between the self-reported price paid per pack and the targeted price, $10. In the third scenario, we used the price difference from the second scenario plus the price promotion estimate from Pesko et al.10 Each simulation was repeated 1,000 times to generate 95% CIs, using uniform distributions for model inputs. We calculated the estimated impacts on smoking population at runtime of each simulation based on fixed values of the state population, by age.

RESULTS

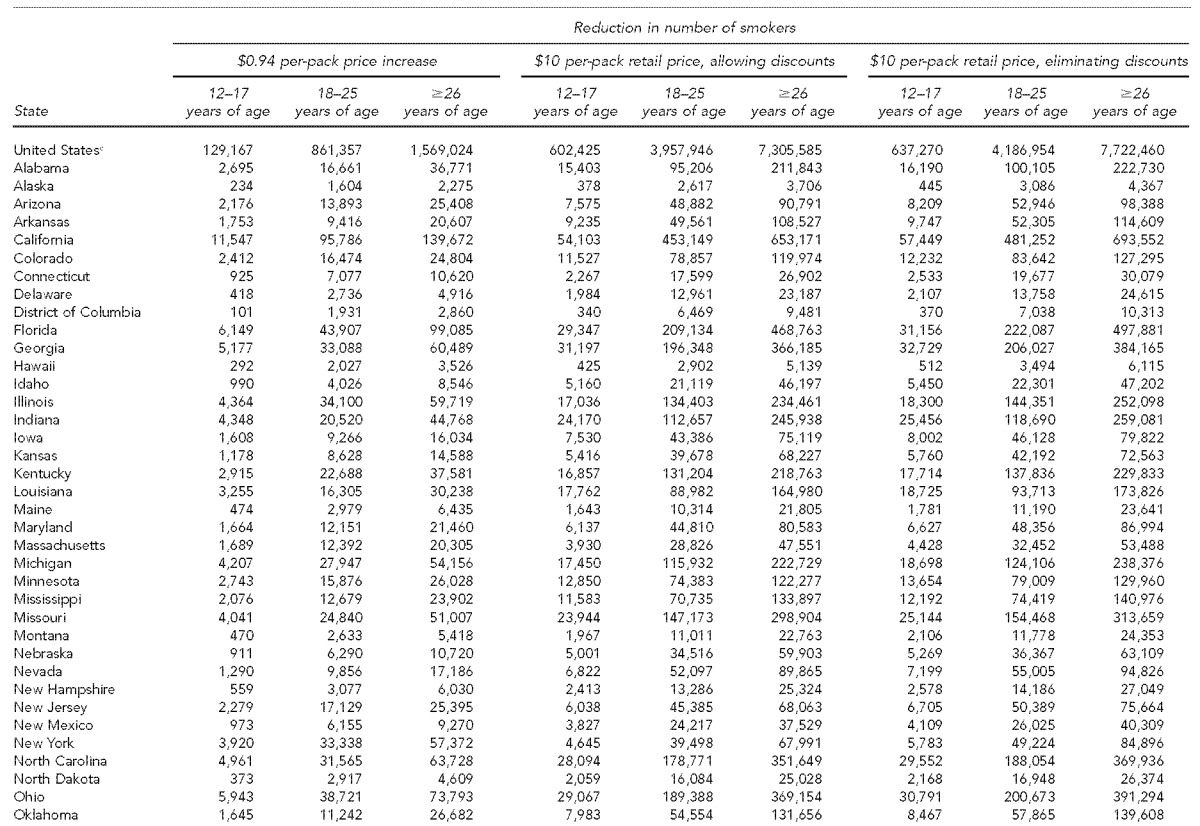

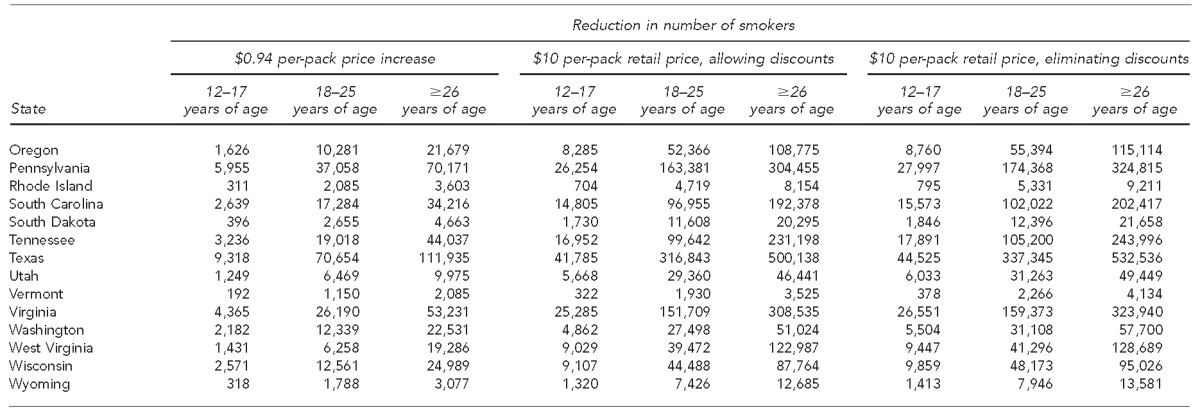

A $0.94 per-pack cigarette price increase could result in 129,167 fewer youth cigarette smokers aged 12–17 years, a 0.5 percentage-point decrease in prevalence; 861,357 fewer young adult smokers aged 18–25 years, a 2.5 percentage-point decrease in prevalence; and 1,569,024 fewer adult smokers aged ≥26 years, a 0.8 percentage-point decrease in prevalence (Tables 1 and 2). A $10 per-pack retail price, allowing discounts, could result in 602,425 fewer teen cigarette smokers, a 2.4 percentage-point decrease in prevalence; 3,957,946 fewer young adult cigarette smokers, an 11.6 percentage-point decrease in prevalence; and 7,305,585 fewer adult smokers aged $26 years, a 3.6 percentage-point decrease in prevalence. The effects of a $10 per-pack average retail price, eliminating discounts, were most robust: 637,270 fewer teen cigarette smokers, a 2.5 percentage-point decrease in prevalence; 4,186,954 fewer young adult cigarette smokers, a 12.2 percentage-point decrease in prevalence; and 7,722,460 fewer adult cigarette smokers ≥26 years of age, a 3.8 percentage-point decrease in prevalence. This third scenario, which eliminated discounts, resulted in 680,728 total fewer smokers—more than the total population of Vermont—compared with the second scenario, which allowed discounts.12 Reductions in smoking prevalence would be expected to occur within one year of implementation of the price interventions.

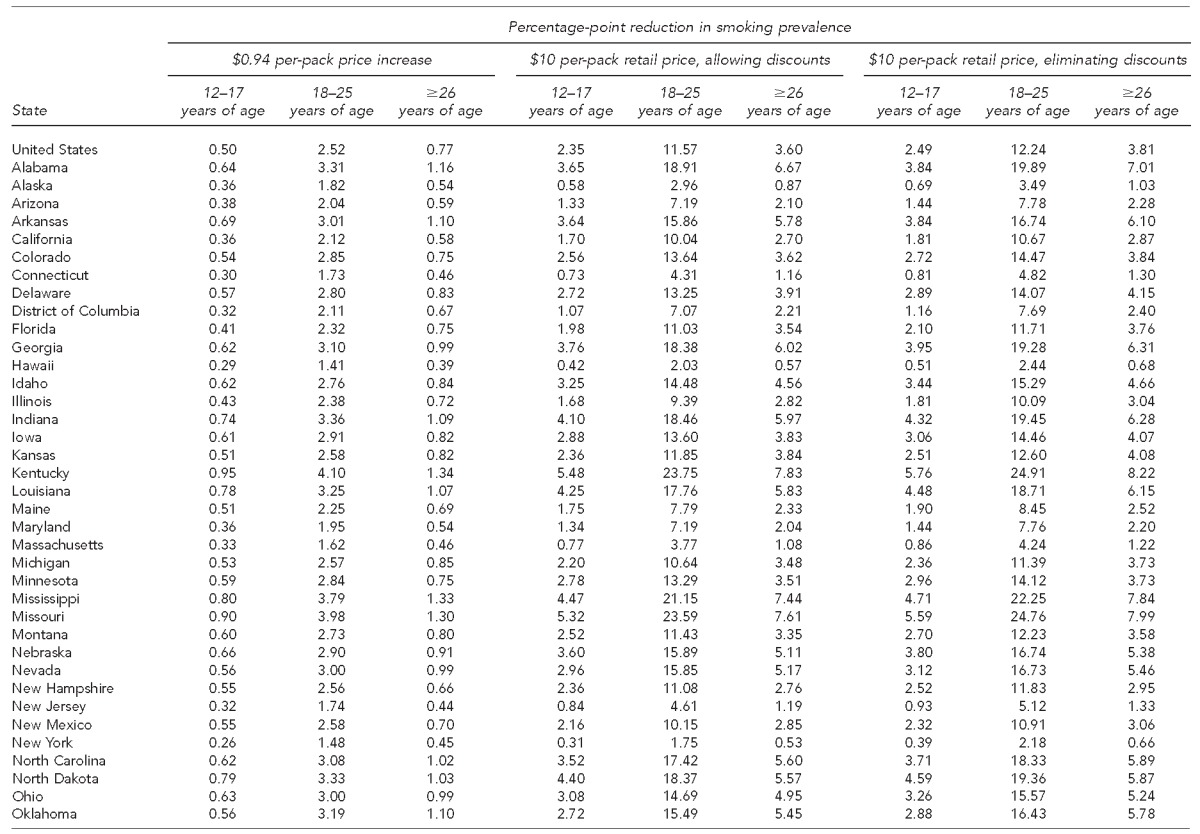

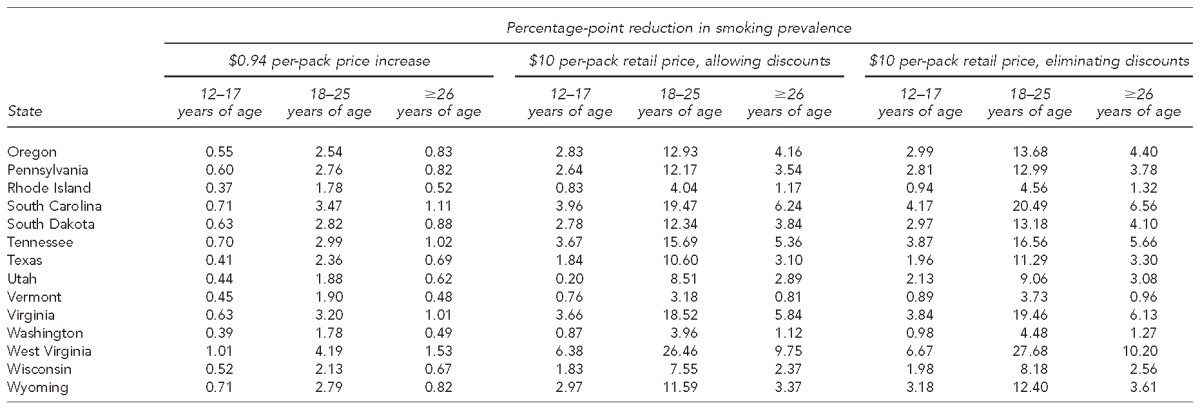

Table 1.

Projected reductions in cigarette smoking prevalence one year after implementation of three price scenarios, by age and state, United Statesa,b

95% confidence intervals are available from the author.

Reductions were estimated based on state-specific smoking prevalence from the 2012/2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Average per-pack retail prices by state came from the 2010–2011 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey, adjusted to 2013 U.S. dollars. Price elasticity estimates by age group were obtained from a literature review by the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Data sources: (1) Census Bureau (US). Population estimates: historical data. 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 21]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/historical/index.html; (2) Guide to Community Preventive Services. Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure: interventions to increase the unit price for tobacco products [cited 2014 Jul 21]. Available from: www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco/increasingunitprice.html; and (3) Department of Health and Human Services (US), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health [cited 2015 Jul 21]. Available from: https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm

Table 2.

Projected reductions in the number of cigarette smokers one year after implementation of three price scenarios, by age and state, United Statesa,b

95% confidence intervals are available from the author.

Reductions were estimated based on state-specific smoking prevalence from the 2012/2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Average per-pack retail prices by state came from the 2010–2011 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey, adjusted to 2013 U.S. dollars. Price elasticity estimates by age group were obtained from a literature review by the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Data sources: (1) Census Bureau (US). Population estimates: historical data. 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 21]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/historical/index.html; (2) Guide to Community Preventive Services. Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure: interventions to increase the unit price for tobacco products [cited 2014 Jul 21]. Available from: www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco/increasingunitprice.html; and (3) Department of Health and Human Services (US), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health [cited 2015 Jul 21]. Available from: https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm

cBecause the results for the United States are generated from an independent simulation, they are not necessarily the sum of state estimates.

Findings varied by state according to state smoking prevalence, population, and baseline retail cigarette price, including state excise taxes. For all three scenarios, states with the lowest excise tax rates and highest smoking prevalence would experience the greatest declines in smoking prevalence. For example, with a $10 per-pack retail price and no discounts, the smoking prevalence among West Virginia's teens, young adults, and adults ≥26 years of age could decline by 6.7, 27.7, and 10.2 percentage points, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Our findings revealed that the three price scenarios would produce rapid and dramatic declines in smoking prevalence. Each price intervention would produce the greatest reductions in smoking prevalence among young adults aged 18–25 years, which has important implications for reducing future tobacco-related disease and death. Given that approximately one in three smokers is projected to die early of a smoking-related disease, a $10 per-pack retail price and no discounts would be expected to avert the early deaths of approximately 1.5 million U.S. youth and young adults.1 Even a $0.94 per-pack federal cigarette tax increase would be expected to avert more than 300,000 early deaths, while reducing geographic disparities in tobacco use, with the greatest declines in underage smoking occurring in Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, and West Virginia.

Tobacco price increases help reduce smoking-related health disparities, including among teen and lower-income smokers.13,15 Calls to state quitlines increase after cigarette tax increases, and quitlines improve the chances of quitting success and are effective with low-income and racially/ethnically diverse populations.15,16 By dedicating a portion of local, state, and federal tax revenues to tobacco control efforts, governments at each level can (1) invest in evidence-based tobacco prevention efforts and (2) help smokers, who bear the greatest burden of cigarette taxes, with support and encouragement to quit, including high-impact media campaigns, tobacco quitlines, and evidence-based cessation treatment and counseling. Medicaid enrollees who attempt to quit smoking in response to a tax increase have an increased chance of successfully quitting smoking if their state Medicaid programs cover additional cessation treatments and remove barriers to coverage.17

Price-discounting promotions increase youths' progression from experimentation to established smoking and undermine smokers' attempts to quit.18–20 The tobacco industry, which is aware of the inverse relationship between cigarette prices and smoking, spent $6.99 billion on cigarette discounts in 2012.21 Internal industry documents note that “price … is the main driving force for quitting” and that price promotions target young adults.22,23 Local tobacco control efforts have begun to address this issue, beginning with bans in New York City and Providence, Rhode Island, on the retail redemption of coupons and multipack discounts. Courts have since upheld these bans.24,25

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the models did not account for non-cigarette combusted tobacco products (e.g., cigars) because state data were not available on current use of any combusted tobacco product or on self-reported prices paid for any combusted tobacco product. Declines in cigarette smoking prevalence may not signify declines of the same magnitude in any combusted tobacco use and smoking-related deaths. Similarly, the model did not account for potential increases in dual use of cigarettes and lower-priced non-combusted tobacco products, including electronic cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. Second, the model used 2012/2013 NSDUH smoking prevalence estimates, which were the latest state representative data by age group available at the time of analysis and, therefore, did not account for declines that have occurred since 2013. Estimates of smoking prevalence tend to be higher in NSDUH than in other surveillance systems because of differing definitions of current smoker; NSDUH does not require past-30-day smokers to also report having smoked 100 cigarettes in a lifetime. Thus, use of NSDUH estimates may have generated larger declines in smoking prevalence than use of estimates from other surveys, such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey. Third, the latest available TUS-CPS estimates for cigarette prices paid did not account for tax increases or price discounts that occurred since 2011. Finally, the models did not account for non-price factors proven to reduce smoking prevalence, such as smoke-free air laws, high-impact media campaigns, or comprehensive statewide tobacco-control programs.1

CONCLUSION

Cigarette prices are far below the Surgeon General's $10 per-pack retail price target. Raising prices by $0.94 or to $10 per pack, eliminating price discounts, and dedicating a portion of revenues to evidence-based tobacco control efforts could substantially reduce cigarette smoking prevalence and smoking-related deaths among youth, young adults, and older adults.

Footnotes

Terry Pechacek receives unrestricted research funding support from Pfizer, Inc. (“Diffusion of Tobacco Control Fundamentals to Other Large Chinese Cities,” Michael Eriksen, Principal Investigator). The authors thank Nishika Vidanage, MPH, MA, Carter Consulting Inc., for her contributions to this article.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC. All data used in this research were secondary, de-identified, publicly available data. As such, the study was deemed to be non-human subjects research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Atlanta: HHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. The health consequences of smoking—fifty years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Atlanta: HHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnie RJ, editor. Institute of Medicine. Ending the tobacco problem: a blueprint for the nation. Washington: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson LM, Avila Tang E, Chander G, Hutton HE, Odelola OA, Elf JL, et al. Impact of tobacco control interventions on smoking initiation, cessation, and prevalence: a systematic review. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:961724. doi: 10.1155/2012/961724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orzechowski W, Walker RC. Vol. 49. Arlington (VA): Orzechowski and Walker; 2014. The tax burden on tobacco: historical compilation. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The White House (US), Office of Management and Budget. Analytical perspectives: budget of the U.S. government, fiscal year 2017 [cited 2016 Mar 17] Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2017/assets/spec.pdf.

- 7.Roeseler A, Solomon M, Beatty C, Sipler AM. The Tobacco Control Network's policy readiness and stage of change assessment: what the results suggest for moving tobacco control efforts forward at the state and territorial levels. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22:9–19. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health [cited 2015 Jul 21] Available from: https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm.

- 9.Department of Commerce (US), Census Bureau. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (2010–2011) [cited 2015 Apr 1] Available from: http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/tus-cps.

- 10.Pesko MF, Xu X, Tynan MA, Gerzoff RB, Malarcher AM, Pechacek TF. Per-pack price reductions available from different cigarette purchasing strategies: United States, 2009–2010. Prev Med. 2014;63:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Labor (US), Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index [cited 2015 Jul 21] Available from: www.bls.gov/cpi.

- 12.Census Bureau (US) Population estimates: historical data. 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 21] Available from: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/historical/index.html.

- 13.Guide to Community Preventive Services. Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure: interventions to increase the unit price for tobacco products [cited 2014 Jul 21] Available from: www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco/increasingunitprice.html.

- 14.StataCorp. College Station (TX): StataCorp; 2015. Stata®: Release 14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrelly MC, Bray JW. Responses to cigarette prices by race/ethnicity, income, and age groups—United States, 1976–1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(29):605–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, et al. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services (US), Public Health Service; 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical Practice Guideline. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singleterry J, Jump Z, DiGiulio A, Babb S, Sneegas K, MacNeil A, et al. State Medicaid coverage for tobacco cessation treatments and barriers to coverage—United States, 2014–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(42):1194–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6442a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slater SJ, Chaloupka FJ, Wakefield M, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM. The impact of retail cigarette marketing practices on youth smoking uptake. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:440–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis RM, Gilpin EA, Loken B, Viswanath K, Wakefield SA, editors. Monograph 19: the role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health (US), National Cancer Institute; 2008. Also available from: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/19/index.html [cited 2016 Mar 9] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Federal Trade Commission (US) Federal Trade Commission cigarette report for 2012. 2015 [cited 2015 Jul 6] Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2012/150327-2012cigaretterpt.pdf.

- 22.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Raising cigarette taxes reduces smoking, especially among kids (and the cigarette companies know it) [cited 2015 Jul 24] Available from: http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0146.pdf.

- 23.Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM, Morley CP, Horan JK. Tax, price and cigarette smoking: evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl I):i62–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Association of Tobacco Outlets, Inc. v. City of New York, 27 F.Supp.3d 415 (S.D.N.Y. June 18, 2014)

- 25. National Association of Tobacco Outlets, Inc. v. City of Providence, Rhode Island, 731 F.3d 71 (1st Cir. 2013)