Abstract

Objective

We determined estimates of homicide among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) compared with non-Hispanic white people to characterize disparities and improve AI/AN classification in incidence and mortality reporting.

Methods

We linked 1999–2009 death certificate data with Indian Health Service (IHS) patient registration data to examine death rates from homicide among AI/AN and non-Hispanic white people. Our analysis focused primarily on residents of IHS Contract Health Service Delivery Area counties and excluded Hispanic people to avoid underestimation of incidence and mortality in AI/ANs and for consistency in our comparisons. We used age-adjusted death rates per 100,000 population and stratified our analyses by sex, age, and IHS region.

Results

Death rates per 100,000 population from homicide were four times higher among AI/ANs (rate = 12.1) than among white people (rate = 2.8). Homicide rates for AI/ANs were highest in the Southwest (25.6 and 6.9 for males and females, respectively) and in Alaska (17.7 and 10.3 for males and females, respectively). Disparities between AI/ANs and non-Hispanic white people were highest in the Northern Plains region among men (rate ratio [RR] = 9.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 8.5, 11.3) and among those aged 25–44 years (RR59.0, 95% CI 7.5, 10.7) and 0–24 years (RR57.4, 95% CI 6.1, 8.9).

Conclusion

Death rates from homicide among AI/ANs were higher than previously reported and varied by sex, age, and region. Violence prevention efforts involving a range of stakeholders are needed at the community level to address this important public health issue.

Although overall homicide rates have declined in the United States during the past two decades (from 9.3 per 100,000 population in 1992 to 4.8 per 100,000 population in 2010),1 homicide rates among males, adolescents, young adults, and non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) are substantially elevated.2 According to a U.S. Department of Justice report, the rate of violent crimes against AI/ANs was twice the rate of the U.S. resident population for the years 1992–2002. Additionally, the rate of violent crime against AI/ANs aged 25–34 years was more than 2.5 times the rate for all people of the same age.3

The U.S. homicide rate decreased by 8% during 2007–2009 (from 6.1 per 100,000 population in 2007 to 5.5 per 100,000 population in 2009). In 2009, homicide rates were lower for every racial/ethnic group except for AI/ANs, whose homicide rate increased by 15% (from 7.8 per 100,000 population in 2007 to 9.0 per 100,000 population in 2009). For AI/ANs aged 15–29 years, the homicide rate increased for both males and females. In 2012, homicide was the third leading cause of death among AI/ANs aged 10–24 years.2 The Indian Health Service (IHS), which is the principal health-care provider for AI/ANs, reported that the overall homicide rate (11.0 per 100,000 population) for the years 2007–2009 was almost twice as high among AI/ANs than among the U.S. resident population for 2008 (5.9 per 100,000 population). For 2007–2009, AI/AN men aged 25–34 years were 4.6 times more likely than AI/AN women of the same age to die from homicide.4 These statistics, particularly among AI/AN adolescents and young adults who comprise a relatively greater proportion of the overall AI/AN population compared with other racial/ethnic groups,4 are cause for concern.

Previous reports on homicides among the AI/AN population did not adjust for race misclassification on death certificates; therefore, they likely underestimated homicide rates for the AI/AN population.1–3 We used an established method5 to analyze mortality data for 1999–2009 to calculate more accurate estimates of homicide among the AI/AN population and compared these rates with those of non-Hispanic white people for the same time period. We also examined homicide rates by sex, age, and IHS region to better inform local public health and violence prevention efforts in this population.

METHODS

Population estimates

Methods for generating the analytic mortality files are described in detail elsewhere.5 Briefly, we used population estimates for 1999–2009 from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), adjusted for the population shifts resulting from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, as denominators to calculate death rates. Bridged single-race data allowed for comparability between the pre- and post-2000 racial/ethnic population estimates during the study period.6,7 Preliminary analyses revealed that the bridged intercensal population estimates substantially overestimated AI/AN people of Hispanic origin; therefore, we limited our analyses to non-Hispanic AI/ANs.5 We chose non-Hispanic white (hereinafter, white) people as the most homogenous referent group.

Death records

Death certificate data are compiled by each state and sent to NCHS, where personal identifiers are removed and they are edited for consistency. NCHS makes this information available to the research community as part of the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) and includes fields such as multiple cause of death, state of residency, age, sex, and race/ethnicity.8 NCHS applies a bridging algorithm nearly identical to that used by the U.S. Census Bureau to assign a single race to decedents whose death certificates indicate multiple races.9 We coded the underlying cause of death for this analysis according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10).10 For deaths caused by homicide, we used ICD-10 codes X85–Y09 (assault) and Y87.1 (sequelae of assault).

Data linkage and analysis file

We linked death certificate data in the National Death Index to the IHS patient registration database to identify AI/AN decedents misclassified as non-AI/AN.11 The IHS patient registration database contains medical information about AI/ANs who are members of federally recognized tribes and who use services provided by IHS. After this linkage, we added a flag indicating a positive link to IHS to the NVSS mortality file as another indicator of AI/AN ancestry. We combined this file with population estimates to create the analytic file AI/AN-U.S. Mortality Database (AMD) in SEER*Stat, version 8.1.2,12 which included all deaths for all races/ethnicities reported to NCHS from 1990 to 2009. We included analyses for 1999 to 2009 to reflect a more recent time frame. For our study, we based the identification of race for deaths among AI/ANs in our analysis on the death certificate or the information derived from data linkages between the IHS patient registration database and the National Death Index.

Geographic coverage

We restricted our analyses to IHS Contract Health Service Delivery Area (CHSDA) or Tribal Service Delivery Area counties that, in general, encompass federally recognized tribal reservations or off-reservation trusts or are adjacent to them. The IHS uses CHSDA residence to determine eligibility for services not directly available from the IHS. Linkage studies have indicated lower rates of misclassification of race for AI/ANs in these counties. CHSDA counties also have a higher proportion of AI/ANs relative to the total population than do non-CHSDA counties, with 64% of the U.S. AI/AN population residing in the 637 CHSDA counties.5,11 Although CHSDA counties are less geographically representative than non-CHSDA counties, we restricted our analyses to CHSDA counties for death rates to improve accuracy in interpreting mortality statistics for AI/ANs relative to the general population.

We completed analyses for all regions combined and by IHS region: Alaska, Northern Plains, Southern Plains, Southwest, Pacific Coast, and East. We defined IHS regions as follows: Alaska; Northern Plains (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming); Southern Plains (Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas); Southwest (Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah); Pacific Coast (California, Hawaii, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington State); and East (Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C.). The percentage of AI/ANs in CHSDA counties compared with AI/ANs in all counties were: 68% in the Northern Plains, 100% in Alaska, 76% in the Southern Plains, 91% in the Southwest, 71% in the Pacific Coast, 18% in the East, and 64% in the United States. Additional details about CHSDA counties and IHS regions are provided elsewhere.5 Identical or similar regional analyses were used in other health-related studies focusing on AI/ANs.13–15

Statistical methods

We used SEER*Stat software to directly adjust all rates, expressed per 100,000 population, by age to the 2000 U.S. standard population.16 Using the age-adjusted death rates, we calculated standardized rate ratios (RRs), which compare homicide rates for AI/ANs with rates for white people. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for age-adjusted rates and RRs based on methods described by Tiwari et al. using SEER*Stat version 8.0.2.17 We set statistical significance at p,0.05.

RESULTS

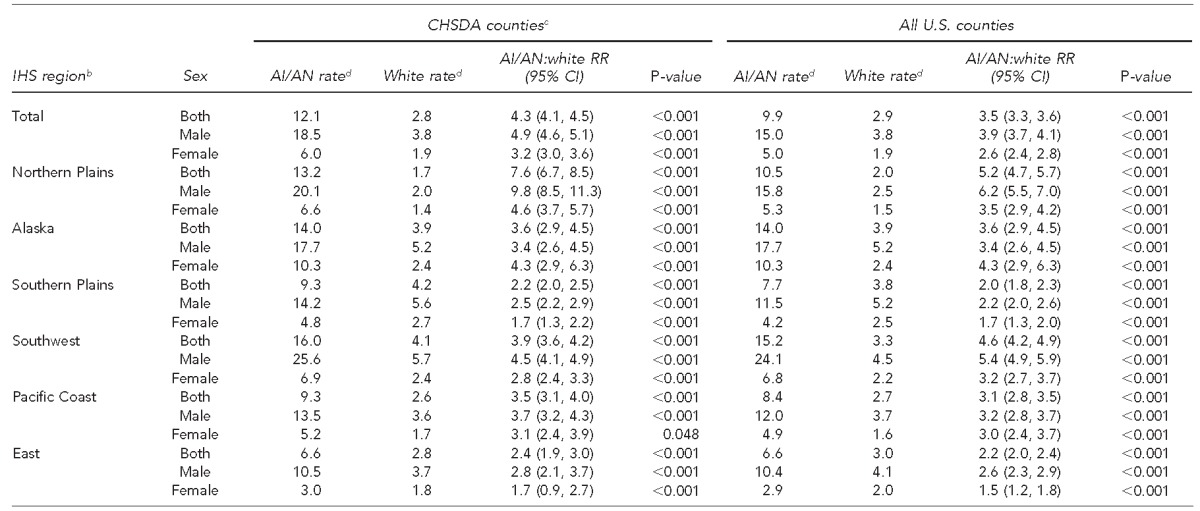

For all regions combined and for each region, death rates for homicide among AI/ANs were higher in CHSDA counties than in all counties combined (Alaska—where all counties are CHSDA counties—was an exception) (Table 1). Overall, and in each IHS region, AI/AN males had higher homicide death rates than AI/AN females. Death rates were highest among AI/AN males in the Southwest (25.6 per 100,000 population) and the Northern Plains (20.1 per 100,000 population). Death rates among AI/AN females were highest in Alaska (10.3 per 100,000 population) and the Southwest (6.9 per 100,000 population). For both sexes combined, death rates for AI/ANs were highest in the Southwest (16.0 per 100,000 population) and Alaska (14.0 per 100,000 population); rates among AI/ANs were lowest in the East (6.6 per 100,000 population). Death rates for homicide among white people ranged from 1.7 per 100,000 population in the Northern Plains to 4.2 per 100,000 population in the Southern Plains (Table 1).

Table 1.

Death rates for assault (homicide) among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) and white people, by Indian Health Service (IHS) region and sex, United States, 1999–2009a

Data source: National Cancer Institute. AI/AN-U.S. mortality database.

bIHS regions are defined as follows: Alaska; Northern Plains (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming); Southern Plains (Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas); Southwest (Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah); Pacific Coast (California, Hawaii, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington State); and East (Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C.).

cIHS CHSDAs encompass federally recognized tribal reservations or off-reservation trusts or are adjacent to them. IHS uses CHSDA residence to determine eligibility for services not directly available from IHS. Linkage studies have indicated lower rates of misclassification of race for AI/ANs in these counties. The CHSDA counties also have a higher proportion of AI/ANs relative to the total population than do non-CHSDA counties, with 64% of the U.S. AI/AN population residing in the 637 CHSDA counties.

dPer 100,000 population

CHSDA = Contract Health Service Delivery Area

RR = rate ratio

CI = confidence interval

Homicide rates by sex and region

Overall, the homicide rate among AI/AN males was nearly five times higher than the rate for white males (RR=4.9, 95% CI 4.6, 5.1). Sex-specific RRs for AI/ANs compared with white people were highest for males in the Northern Plains region (RR=9.8, 95% CI 8.5, 11.3) followed by females in the Northern Plains region (RR=4.6, 95% CI 3.7, 5.7), males in the Southwest (RR=4.5, 95% CI 4.1, 4.9), and females in Alaska (RR=4.3, 95% CI 2.9, 6.3) (Table 1).

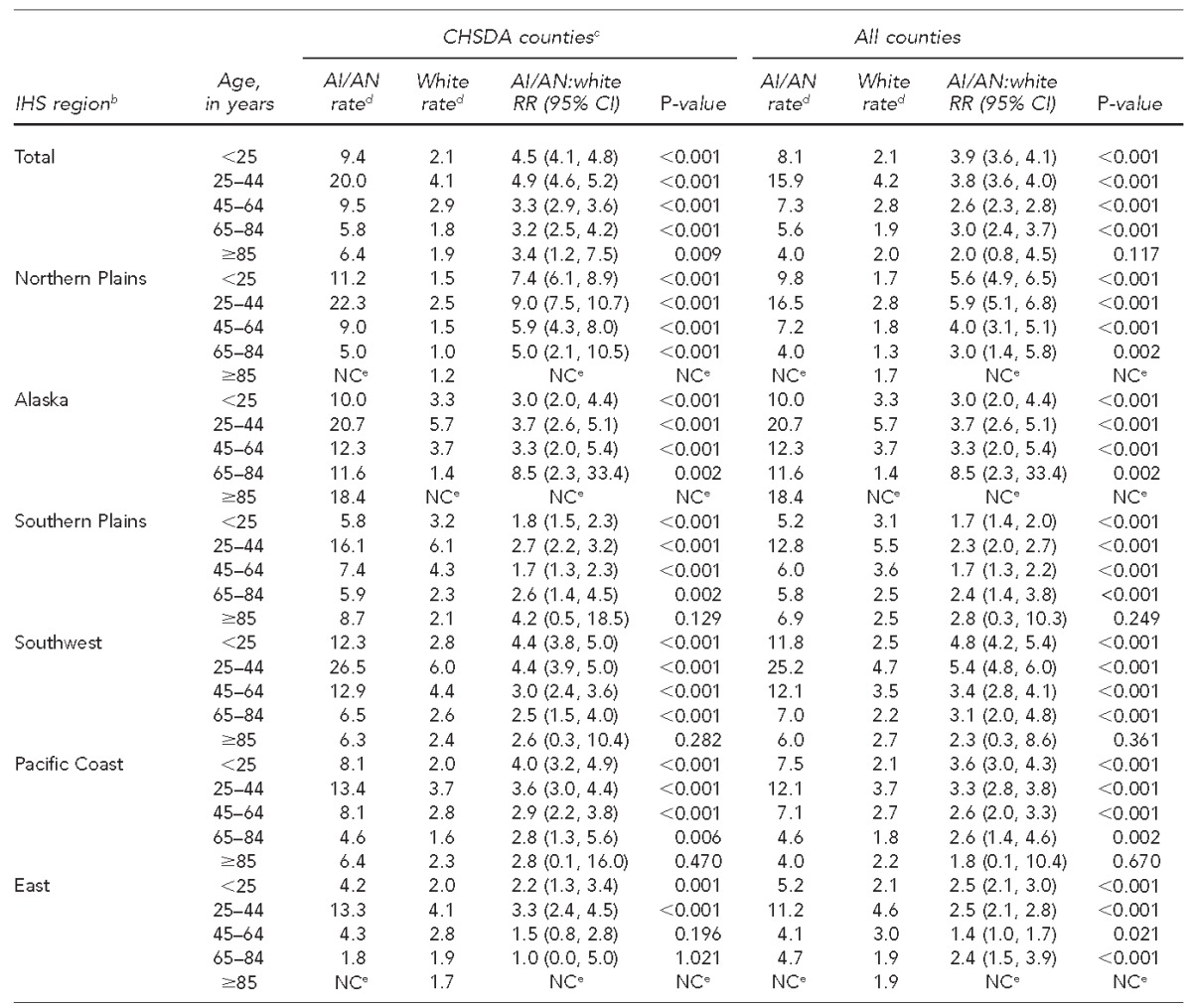

Homicide rates by age and region

Overall, age group–specific RRs for homicides among AI/ANs compared with white people were higher for every age group (Table 2). Death rates per 100,000 population for AI/ANs were highest among those aged 25–44 years (20.0) and lowest among those aged 65–84 years (5.8). Rates per 100,000 population among white people were also highest among those aged 25–44 years (4.1) and lowest among those aged 65–84 years (1.8). Age group–specific RRs for homicides among AI/ANs compared with white people were highest and significant among those aged 25–44 years in every region (Table 2).

Table 2.

Death rates for assault (homicide) among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) and white people, by Indian Health Service (IHS) region and age, United States, 1999–2009a

Data source: National Cancer Institute. AI/AN–U.S. mortality database.

bIHS regions are defined as follows: Alaska; Northern Plains (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming); Southern Plains (Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas); Southwest (Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah); Pacific Coast (California, Hawaii, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington State); and East (Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C.).

cIHS CHSDAs encompass federally recognized tribal reservations or off-reservation trusts or are adjacent to them. IHS uses CHSDA residence to determine eligibility for services not directly available from IHS. Linkage studies have indicated lower rates of misclassification of race for AI/ANs in these counties. The CHSDA counties also have a higher proportion of AI/ANs relative to the total population than do non-CHSDA counties, with 64% of the U.S. AI/AN population residing in the 637 CHSDA counties.

dPer 100,000 population

e≤10 cases were reported. As such, rates and RRs could not be calculated.

CHSDA = Contract Health Service Delivery Area

RR = rate ratio

CI = confidence interval

NC = not calculable

DISCUSSION

Our study showed significantly higher rates of death from homicide among AI/ANs than among white people, in every age group, among both sexes, and across CHSDA counties for all IHS regions (except for those aged 65–84 years in the East region, where rates were virtually the same). Among AI/ANs, death rates varied by sex, age group, and IHS region. This regional analysis showed disparities in death rates between AI/ANs and white people that are not shown when rates are aggregated across regions. Regional disparities in homicide death rates between AI/ANs and white people can be used to inform public health approaches to violence prevention in the AI/AN population.

Although the scientific literature indicates that white males are at higher risk for homicide than white females,1,2 we determined that AI/AN males in the Northern Plains were nearly 10 times more likely than white males in the Northern Plains to die from homicide. Adolescent and young adult AI/AN males were at a much higher risk for death from homicide than AI/AN females, white males, and females in the same age groups, particularly in the Northern Plains, the Southwest, and Alaska. In the highest-risk age group (25–44 years), AI/AN males and females had a nearly fivefold greater risk for homicide than white males and females. These rates are higher than previously reported,1–4 and RRs comparing homicide rates of AI/ANs with those of white people by region provide important information for regional and local public health prevention efforts aimed at reducing health disparities among AI/ANs.

Studies involving AI/ANs often cite racial misclassification as a study limitation, resulting in an underestimation of the cases of disease or disease-specific mortality in question. One study identified 414 of 2,819 (14.7%) AI/AN decedents as misclassified on Washington State death certificates after linking the Northwest Tribal Registry and the Washington State death files.18 Similarly, during a 14-year period (1990–2003), 17% of American Indian decedents in North Carolina were misclassified on the death certificate.19 Racial misclassification can occur when recorded racial information is based on observations by health-care personnel rather than on reports given by the patient or the patient's family. Misclassifying AI/ANs with Hispanic surnames as Latino and limited AI/AN data entry fields on medical records or intake forms all contribute to misclassification. This linkage study helps to improve, but not entirely eliminate, the misclassification of AI/ANs who died from homicide and allows for improved estimates of homicide mortality among AI/AN populations.

Risk and protective factors

Large multinational studies have identified numerous socioeconomic indicators (i.e., economic opportunity, income inequality, poverty) as important predictors of higher rates of homicide.20 Socioeconomic disparities between AI/ANs and other racial/ethnic groups are widely reported in the literature. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, more than 25% of the AI/AN population was living below the federal poverty level compared with 12% of all racial/ethnic groups in the United States; nearly 35% of AI/AN children younger than 5 years of age were living in poverty compared with 18% of all racial/ethnic groups in the United States. More than 13% of AI/AN males aged ≥16 years were unemployed compared with 6% of males in all racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Unemployment rates were 11.7% for female AI/ANs and 5.8% for white females.4

Economic development at the community level may ameliorate poverty in some AI/AN communities and could lead to improved health outcomes.21 Education and job training programs may also help raise educational attainment and socioeconomic status. Recent studies suggest that establishing business improvement districts, an economic development strategy that includes local investment in street cleaning/beautification and public safety, may be one effective intervention strategy.21,22

Previous work suggests that cumulative exposure to high rates of neighborhood poverty may be associated with higher levels of alcohol consumption.23 This finding is important because about 62% of American Indian victims experienced violence by an offender using alcohol compared with 42% for the national average for the years 1992–2002.3 In particular, young AI/AN males who are unemployed are more likely than young AI/AN females who are unemployed to engage in risk-taking behaviors, including alcohol and substance abuse, that increase the risk for serious injury, including homicide.24,25 Studies assessing the impact of more restrictive alcohol policies are ongoing.21

Culturally competent, accessible behavioral health services have consistently been a top priority for AI/AN tribal leaders. Research suggests that culturally competent,25 sex-tailored,24,26 and trauma-informed26 behavioral health services are more likely than current delivery models to produce improved outcomes. These aspects of health-care delivery are usually community-specific, particularly among AI/ANs. Community-based multidisciplinary approaches to violence prevention programming have been shown to be effective.27 Reducing the high rates of homicide among AI/AN populations will require such an approach, one that includes at a minimum behavioral health services, school officials and staff members, law enforcement, court systems oriented to drug courts and alternatives to detention, and community members working together to reduce risk factors and promote protective factors. A study published in 2013 also suggests that American Indian public school students are disproportionately victims of potential bullying,28 which may be related to their lower rates of high school and college graduation. Changing cultural norms about the acceptability of violence and building positive community connections through community events may be effective intervention strategies.20,28 Potential relationships between bullying and violence among AI/ANs is an area in need of exploration.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, although linkage with the IHS patient registration database improved the classification of race for AI/AN decedents, the problem of misclassification was not completely resolved because AI/ANs who are not members of federally recognized tribes are not eligible for services provided by IHS and, therefore, are not represented in the IHS database. Additionally, some decedents who are eligible for but have never used IHS services were not included in the IHS registration database.

Second, the findings from CHSDA counties highlighted in our findings do not represent all AI/AN populations in the United States or in individual IHS regions.11 In particular, the East region includes only 18% of the total AI/AN population in that region. As such, rates of homicide for AI/ANs living in the East may have been underestimated. Furthermore, the analyses based on CHSDA designation excluded many AI/AN decedents in urban areas that were not part of a CHSDA county. AI/AN residents of urban areas differ from all AI/ANs by poverty status, health-care access, and other factors that may influence mortality trends.29

Third, these analyses revealed less variation for white people than for AI/ANs in regional analyses in CHSDA counties only. Alternative groupings of states or counties might reveal a different level of variation for white people. Fourth, federally recognized tribes vary substantially in the proportion of Native American ancestry required for tribal membership and, therefore, for eligibility for services provided by IHS. Whether and how this discrepancy in tribal membership requirements may influence our findings is unclear, although our findings are consistent with those of prior reports. Finally, although the exclusion of Hispanic AI/ANs from the analyses reduced the overall death count among AI/ANs by <5%, it may have disproportionately affected the homicide rates in some states and to a lesser extent in some regions.

CONCLUSION

This article improves on previous observations of high death rates from homicide among AI/ANs compared with white people by using more accurate data obtained by linkages with IHS registration data and by focusing attention on CHSDA counties, which evidence suggests have a lower rate of race misclassification. We found elevated homicide rates among AI/ANs that varied by region, sex, and age group. A culturally appropriate, multidisciplinary, and multilevel effort involving public officials and private citizens is needed to address this important public health issue.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Indian Health Service (IHS). The IHS determined this project to constitute public health practice and not research; therefore, no formal institutional review board approvals were required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper A, Smith EL. Washington: Department of Justice (US), Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs; 2011. Homicide trends in the Unites States, 1980–2008. Also available from: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf [cited 2016 May 25] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logan JE, Hall J, McDaniel D, Stevens MR. Homicides—United States, 2007 and 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Suppl. 2013;62(3):164–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry SW. Washington: Department of Justice (US), Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2004. A BJS statistical profile, 1992–2002: American Indians and crime. Also available from: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aic02.pdf [cited 2016 Mar 22] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Indian Health Service (US) Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2015. Trends in Indian health: 2014 edition. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espey DK, Jim MA, Richards TB, Begay C, Haverkamp D, Roberts D. Methods for improving the quality and completeness of mortality data for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 3):S286–94. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics (US) U.S. Census populations with bridged race categories [cited 2015 Dec 2] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race.htm.

- 7.National Cancer Institute (US), Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Adjusted populations for the counties/parishes affected by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita [cited 2016 Mar 22] Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/hurricane_adj.html.

- 8.National Center for Health Statistics (US) National Vital Statistics System [cited 2016 Mar 22] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss.htm.

- 9.National Center for Health Statistics (US) NCHS procedures for multiple-race and Hispanic origin data: collection, coding, editing, and transmitting. 2004 [cited 2016 Mar 25] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/Multiple_race_documentation_5-10-04.pdf.

- 10.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2015. International classification of diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jim MA, Arias E, Seneca DS, Hoopes MJ, Jim CC, Johnson NJ, et al. Racial misclassification of American Indians and Alaska Natives by Indian Health Service Contract Health Service Delivery Area. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 3):S295–302. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2013. SEER*Stat version 8.1.2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denny CH, Taylor TL. American Indian and Alaska Native health behavior: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1992–1995. Ethn Dis. 1999;9:403–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiggins CL, Espey DK, Wingo PA, Kaur JS, Wilson RT, Swan J, et al. Cancer among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999–2004. Cancer. 2008;113(5 Suppl):1142–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espey D, Paisano R, Cobb N. Regional patterns and trends in cancer mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1990–2001. Cancer. 2005;103:1045–53. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bureau of the Census (US), Department of Commerce. Washington: Government Printing Office (US); 1996. Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050. Current Population Reports P25-1130. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15:547–69. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stehr-Green P, Bettles J, Robertson LD. Effect of racial/ethnic misclassification of American Indians and Alaskan Natives on Washington State death certificates, 1989–1997. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:443–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buescher P, Mittal M. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics; 2005. Racial disparities in birth outcomes increase with maternal age: recent data from North Carolina. Also available from: http://www.schs.state.nc.us/schs/pdf/SB27.pdf [cited 2016 May 26] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massetti GM, David-Ferdon C. Preventing violence among high-risk youth and communities with economic, policy, and structural strategies. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Suppl. 2016;65(1):57–60. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6501a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouimet M. A world of homicides: the effect of economic development, income inequality, and excess infant mortality on the homicide rate for 165 countries in 2010. Homicide Stud. 2012;16:238–58. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RJ. Tribal casino impacts on American Indians well-being: evidence from reservation-level census data. Contemp Econ Pol. 2013;31:291–300. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerda M, Diez-Roux AV, Tchetgen ET, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe C. The relationship between neighborhood poverty and alcohol use: estimation by marginal structural models. Epidemiology. 2010;21:482–9. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e13539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhoades ER. The health status of American Indian and Alaska Native males. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:774–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyd-Ball AJ, Manson SM, Noonan C, Beals J. Traumatic events and alcohol use disorders among American Indian adolescents and young adults. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:937–47. doi: 10.1002/jts.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brave Heart MY, Elkins J, Tafoya G, Bird D, Salvador M. Wicasa Was'aka: restoring the traditional strength of American Indian boys and men. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2):S177–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen J, Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Hazel KL, Thomas L, Lindley S. The tools to understand: community as co-researcher on culture-specific protective factors for Alaska Natives. J Prev Interv Community. 2006;32:41–59. doi: 10.1300/J005v32n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell EM, Smalling SE. American Indians and bullying in schools. J Indigen Soc Dev. 2013;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urban Indian Health Institute, Seattle Indian Health Board. Reported health and health-influencing behaviors among urban American Indians and Alaska Natives: an analysis of data collected by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Updated July 2008 [cited 2016 Mar 22] Available from: http://www.uihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/health_health-influencing_behaviors_among_urban_indiansupdate-121020081.pdf.