Abstract

The pharmacological effects of intramuscular (IM) administration of alfaxalone combined with medetomidine and butorphanol were evaluated in 6 healthy beagle dogs. Each dog received three treatments with a minimum 10-day interval between treatments. The dogs received an IM injection of alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg (ALFX), medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg (MB), or their combination (MBA) 1 hr after the recovery from their instrumentation. Endotracheal intubation was attempted, and dogs were allowed to breath room air. Neuro-depressive effects (behavior changes and subjective scores) and cardiorespiratory parameters (rectal temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, direct blood pressure, central venous pressure and blood gases) were evaluated before and at 2 to 120 min after IM treatment. Each dog became lateral recumbency, except for two dogs administered the MB treatment. The duration was longer in the MBA treatment compared with the ALFX treatment (100 ± 48 min vs 46 ± 13 min). Maintenance of the endotracheal tube lasted for 60 ± 24 min in five dogs administered the MBA treatment and for 20 min in one dog administered the ALFX treatment. Cardiorespiratory variables were maintained within clinically acceptable ranges, although decreases in heart and respiratory rates, and increases in central venous pressure occurred after the MBA and MB treatments. The MBA treatment provided an anesthetic effect that permitted endotracheal intubation without severe cardiorespiratory depression in healthy dogs.

Keywords: alfaxalone, butorphanol, canine, intramuscular administration, medetomidine

General anesthesia is an indispensable medical technology, and injectable anesthetics are commonly used in modern veterinary practice. However, intravenous (IV) administration is usually difficult and/or impossible in fractious, fearful or excited patients. Thus, the injectable anesthetic agents that can be administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly (IM) are very important and useful for veterinary anesthesia in order to reduce the stress of handling and the risk of injury to both dogs and handlers.

Alfaxalone is a synthetic neuroactive steroid molecule and causes the gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor associated neuro-depression and muscular relaxation [1, 6, 14]. In the past decade, a new alfaxalone formulation solubilized with 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (alfaxalone-HPCD) is approved and used as an IV anesthetic agent for dogs and cats in many countries, because of its properties of smooth induction, rapid recovery and minimal cardiorespiratory depression [4, 12, 19]. Recently, we reported that IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD at 7.5 to 10 mg/kg produced anesthetic effects permitting endotracheal intubation with mild cardiorespiratory depressions in dogs [28]. However, its large dosage volume (0.75 to 1 ml/kg IM) makes the clinical application difficult. In addition, undesirable events including transient muscular tremors and ataxia were observed during recovery from the IM alfaxalone anesthesia in dogs [28].

Maddern et al. [16] reported that premedication with low dose of medetomidine (4 µg/kg IM) and butorphanol (0.1 mg/kg IM) produced marked sparing effects on the anesthetic dose of IV alfaxalone-HPCD in dogs. Lower doses of medetomidine (<5 µg/kg IV) may not provide adequate levels of sedation and analgesia, although that produced less cardiovascular depression compared to higher doses of medetomidine in dogs [20, 22]. Butorphanol combined with low dose of medetomidine produces synergic sedative effects [5]. Therefore, it is expected that a combination of alfaxalone-HPCD, low dose of medetomidine, and butorphanol may reduce the IM dosage volume of alfaxalone-HPCD required for inducing anesthesia with mild cardiorespiratory depression. In addition, premedication with centrally acting sedatives and/or analgesics may improve the quality of recovery from alfaxalone-HPCD anesthesia in dogs [9, 23]. It is also expected that medetomidine and butorphanol combined with alfaxalone-HPCD may provide better quality of anesthesia and recovery by their synergic sedative and analgesic effects. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the anesthetic effects of intramuscular administration of alfaxalone-HPCD combined with medetomidine and butorphanol in dogs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals: Six intact, adult beagle dogs (3 males and 3 females) that were 1 to 5 years of age [2.9 ± 1.5 (mean ± standard deviation) years old] and that weighed 8.6 to 16.8 kg (11.5 ± 3.2 kg) were used for three drug treatments with at least 10 days between each treatment. All dogs used in the present study exhibited the ideal body condition (body condition score 3/5) [2]. Each dog was received in the order of the IM treatment of a combination of alfaxalone-HPCD, medetomidine and butorphanol (MBA), a combination of medetomidine and butorphanol (MB), and alfaxalone-HPCD alone (ALFX). All dogs were judged to be in good physical condition based upon a physical examination. Food was withheld for 12 hr before the each experiment, and water was continuously available. The dogs were cared for according to the principles of the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by Rakuno Gakuen University. The Animal Care and Use Committee of Rakuno Gakuen University approved this study (approved No. VH22B17).

Instrumentation: All dogs were instrumented with arterial and central venous catheters under general anesthesia prior to the administration of each IM drug solution. Anesthesia was induced by mask induction using a vaporizer dial setting at 5% of sevoflurane (Sevoflo, DS Pharma Animal Health Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) with oxygen. Once anesthetized, the dogs were orotracheally intubated, and anesthesia was maintained with vaporizer dial setting at 3.0–3.5% of sevoflurane with oxygen. The dogs were placed in left lateral recumbency for catheter instrumentation. In each dog, 22-gauge catheters (Supercath, Medikit Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were placed into the left cephalic vein and the left dorsal pedal artery. In addition, an 18-gauge catheter 30 cm in length (Intravascular Catheter Kit, Medikit Co., Ltd.) was placed into the cranial vena cava through the right jugular vein after the cervical catheter site was aseptically prepared and infiltrated with 1 mg/kg of 2% lidocaine (2% Xylocaine Astrazeneca, Osaka, Japan). The position of the tip and insertion length of the central venous catheter were approximated and confirmed by pressure waveform. The dogs were infused with lactated Ringer’s solution (Solulact, Terumo Co., Tokyo, Japan) at a rate of 10 ml/kg/hr through the catheter placed into the cephalic vein during the sevoflurane anesthesia. After the completion of catheter placements, the sevoflurane was discontinued, and each dog was extubated when their laryngeal reflex was functional. Each dog was then allowed to recover for 1 hr in a quiet room until the administration of its allocated IM treatment.

Drug administration and data collection: Following the 1 hr recovery period, the dogs received IM alfaxalone-HPCD (Alfaxan, Jurox Pty. Ltd., Rutherford, NSW, Australia) at 2.5 mg/kg (ALFX), medetomidine (Domitor, Nippon Zenyaku Kogyo Co., Ltd., Fukushima, Japan) at 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol (Vetorphal, Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 0.25 mg/kg (MB), or alfaxalone-HPCD at 2.5 mg/kg, medetomidine at 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol at 0.25 mg/kg (MBA) in separate experiments. Maddern et al. [16] showed that the anesthetic induction dose of IV alfaxalone-HPCD can be decreased to around one third by premedication with low dose of medetomidine and butorphanol in dogs. Therefore, the dose of IM alfaxalone-HPCD administration was set at 2.5 mg/kg (one third of anesthetic IM alfaxalone-HPCD dose) in the present study. All IM drug solutions were administered to each dog at total 0.3 ml/kg in volume under manual physical restraint. In the ALFX and MB treatments, the IM drug solution was prepared by mixing appropriate amounts of each product and diluting with normal saline (Otsuka normal saline, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) up to 0.3 ml/kg volume in a single syringe. In the MBA treatment, the IM drug solution was prepared as a mixture of 0.1 ml of medetomidine (1 mg/ml), 2 ml of butorphanol (5 mg/ml) and 10 ml of alfaxalone (10 mg/ml). Thus, the final dose of each drug given to the dogs was medetomidine 2.48 µg/kg, butorphanol 0.248 mg/kg and alfaxalone 2.48 mg/kg in the MBA treatment. In each treatment, the IM drug solution was injected into the dorsal lumbar muscle of the dog by using a syringe with a 23-gauge, 1-inch needle (TOP injection needle, TOP Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The dogs breathed room air and were endotracheally intubated with an endotracheal tube [Endotracheal tube with cuff (I.D. 7.5 to 8.5 mm), Fuji Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan] when possible. The endotracheal tube was removed when the dogs regained their laryngeal reflex. Anesthetic and cardiorespiratory effects were evaluated in the dogs before each IM treatment (baseline) and at 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min after the administration of each IM drug solution.

Evaluation of anesthetic effect: Anesthetic effect was evaluated by the degree of neuro-depression, the quality of anesthetic induction including the ease of endotracheal intubation and the quality of recovery from anesthesia. The neuro-depression produced with each IM treatment was subjectively evaluated by using an existing composite measurement scoring system in dogs [30]. The scoring system consisted of 6 categories: spontaneous posture, placement on side, response to noise, jaw relaxation, general attitude and nociceptive response to toe-pinch. These categories were rated with a score of 0 to 2 for jaw relaxation, 0 to 3 for placement of side, general attitude and toe-pinch response and 0 to 4 for spontaneous posture and response to noise based on the responsiveness expressed by the dogs [30]. Total neuro-depressive score was calculated as the sum of the scores for the 6 categories (a maximum of 19). The qualities of anesthetic induction and recovery were assessed using numerical scoring systems previously used in dogs [28]. A well-trained observer (N. H.) was responsible for evaluation of the anesthetic effect of the treatments using these scoring systems.

In addition, we recorded the periods of time before the dogs lay down in lateral recumbency (Time until onset of lateral recumbency), were intubated (Time until intubation), appeared the first spontaneous movement (Time until spontaneous movement), and appeared their head lift (Time until head lift) and unaided standing (Time until unaided standing), after the start of each IM treatment. The durations of acceptance of endotracheal intubation and maintenance of lateral recumbency were also recorded as the periods of time from the intubation to extubation (Duration of intubation) and from the onset of lateral recumbency to head lift (Duration of lateral recumbency).

Measurements of cardiorespiratory valuables: Lead II electrocardiography (ECG), heart rate (HR; beats/min), respiratory rate (RR; breathes/min), rectal temperature (RT;°C), systolic arterial blood pressure (SABP; mmHg), diastolic arterial blood pressure (DABP; mmHg), mean arterial blood pressure (MABP; mmHg) and central venous blood pressure (CVP; mmHg) were recorded before and after the IM treatment. RR was counted by observing thoracic movements. ECG, HR, RT, SABP, DABP, MABP and CVP were recorded by a patient monitoring system (DS-7210, Fukuda Denshi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). SABP, DABP and MABP were directly measured by connecting the catheter placed in the left pedal artery to a pressure transducer (BD DTXTM Plus DT-4812, Japan Becton, Dickinson and Co., Fukushima, Japan). In addition, CVP was also measured by connecting the catheter placed in the cranial vena cava to a pressure transducer. These pressure transducers were placed at the level of the right atrium.

Arterial blood samples (0.5 ml each) were anaerobically withdrawn from the arterial catheters into a heparinized syringe before and after the IM treatment. The blood samples were analyzed immediately after collection to measure arterial pH (pHa), partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2; mmHg) and carbon dioxide (PaCO2; mmHg), and arterial plasma lactate concentration (Lac; mmol/l) using a blood gas analyzer (GEM Premier 3000, Instrumentation Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan). In addition, arterial bicarbonate concentration (HCO3; mmol/l), base excess (B.E.; mmol/l) and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2;%) were analyzed. The pHa, PaO2 and PaCO2 were corrected for the rectal temperature determined immediately after the blood collection. In the same way, central venous blood samples (0.5 ml each) were anaerobically withdrawn from the central venous catheters and immediately analyzed to obtain central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2;%) using the blood gas analyzer.

Statistical analysis: The total neuro-depressive score was reported as the median ± quartile deviation and was analyzed by the Friedman test to assess changes from baseline values with time for each treatment. Difference in the total neuro-depressive score and the qualities of anesthetic induction and recovery amongst the treatments were compared by the Friedman test with the Scheff test for post hoc comparisons. Anesthetic effect times and cardiorespiratory variables were reported as the mean ± standard deviation. The times were compared by paired t test and one-way (treatment) factorial ANOVA with the Bonferroni test for post hoc comparisons among treatments. The cardiorespiratory variables were analyzed using two-way (treatment and time) repeated measure ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. Observations and/or perceived adverse effects related to drug administration were compared between treatments by using the chi square test. The level of significant was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

The IM administration of each drug solution was accepted and completed without resisting it in all dogs under manual physical restraint by one person. There was no swelling, redness or changes in the skin observed around the injections sites of each dog after IM administration. Immediately after each treatment, nausea like behaviors, such as chewing and increased salivation, were observed in 2 dogs receiving the MB treatment and 3 dogs receiving the MBA treatment; however, the dogs did not exhibit vomiting in all treatment groups.

Anesthetic effects: The times associated with the anesthetic effect of each treatment are shown in Table 1. All dogs became lateral recumbency quite rapidly after the ALFX and MBA treatments with mean onset times of approximately 4 and 7 min, respectively. The times to lateral recumbency was longer and varied more with the MB treatment. In addition, only 4 of 6 dogs went into lateral recumbency following the MB treatment. There was no significant difference in the time of onset of lateral recumbency between the ALFX and MBA treatments (P=0.239). The quality of anesthetic induction after IM treatments is shown in Table 2. The quality of anesthetic induction score did not differ between treatments (P=0.130). The dog scored as 1 (poor) after the MBA treatment showed the same quality of anesthetic induction (score 1) after the MB and ALFX treatments. Endotracheal intubation was achieved in one, 5 and 6 dogs, and maintained in zero, one (17%) and 5 dogs (83%) administered the MB, ALFX and MBA treatments, respectively. In the MBA treatment group, more dogs could be endotracheally intubated (P=0.005). The times of first appearance of spontaneous movement, head lift and unaided standing, and the duration of maintenance of lateral recumbency were considerably longer in the dogs receiving the MBA treatment compared with the dogs receiving the ALFX treatment (P=0.002, P=0.004, P=0.010 and P=0.021, respectively).

Table 1. Times related to anesthetic effect after intramuscular (IM) treatments in dogs.

| IM treatments |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALFX | MB | MBA | ||||

| Time until onset of lateral recumbency (sec) | 224 ± 110 | (n=6) | 850 ± 563 | (n=4) b) | 391 ± 264 | (n=6) |

| Time until intubation (min) | 12 ± 4 | (n=5) c) | 13 | (n=1) c) | 16 ± 6 | (n=6) |

| Time until spontaneous movement (min) | 40 ± 11 | (n=6) | 32 ± 6 | (n=4) b) | 79 ± 22 a) | (n=6) |

| Time until head lift (min) | 41 ± 12 | (n=6) | 48 ± 12 | (n=4) b) | 89 ± 25 a) | (n=6) |

| Time until unaided standing (min) | 59 ± 21 | (n=6) | 80 ± 25 | (n=6) | 123 ± 44 a) | (n=6) |

| Duration of intubation (min) | 20 | (n=1) d) | N/A | (n=0) d) | 60 ± 24 | (n=5) d) |

| Duration of lateral recumbency (min) | 46 ± 13 | (n=6) | 48 ± 28 | (n=4) b) | 100 ± 48a) | (n=6) |

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. N/A: Not applicable. ALFX: alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg administered IM. MB: medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg co-administered IM. MBA: alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg, medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg co-administered IM. We recorded the periods of time before the dogs lay down in lateral recumbency (Time until onset of lateral recumbency), were intubated (Time until intubation), appeared the first spontaneous movement (Time until spontaneous movement), and appeared their head lift (Time until head lift) and unaided standing (Time until unaided standing), after the start of each IM treatment. The durations of acceptance of endotracheal intubation and maintenance of lateral recumbency were also recorded as the periods of time from the intubation to extubation (Duration of intubation) and from the onset of lateral recumbency to head lift (Duration of lateral recumbency). a) Significant difference from the ALFX group (P<0.05). b) Only 4 dogs became lateral recumbency and immobilized after the MB treatment. c) Placement of the endotracheal tube was possible in 5 dogs in the ALFX group and a dog in the MB group. d) Endotracheal intubation was maintained a dog in the ALFX group and 5 dogs in the MBA group.

Table 2. The qualities of anesthetic induction and recovery after intramuscular (IM) treatments in dogs.

| IM treatments |

P value between treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALFX | MB | MBA | ||

| Induction quality [28] | ||||

| Score 1: Poor | 1 | 5 | 1 | P=0.130 |

| Score 2: Moderately smooth | 5 | 1 | 3 | |

| Score 3: Quite smooth | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Score 4: Very smooth | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Recovery quality [28] | ||||

| Score 1: Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | P=0.747 |

| Score 2: Moderately smooth | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Score 3: Quite smooth | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Score 4: Very smooth | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

Data showed the number of dogs. ALFX: alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg administered IM. MB: medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg co-administered IM. MBA: alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg, medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg co-administered IM.

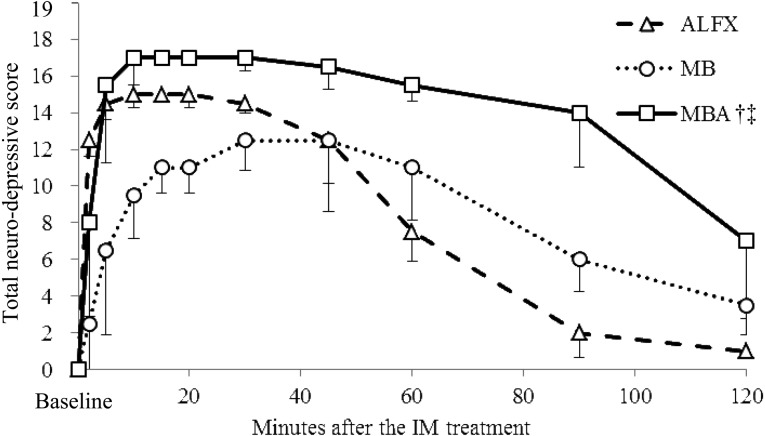

Changes in total neuro-depressive scores for each treatment are presented in Fig. 1. The median total neuro-depressive scores peaked at 10 to 20 min after the ALFX treatment (median total neuro-depressive score 15.0), at 30 to 45 min after the MB treatment (median total neuro-depressive score 12.5) and at 10 to 30 min after the MBA treatment (median total neuro-depressive score 17.0). No dogs showed the maximum score of 19, because toe-pinch responses could still be elicited in all dogs. The total neuro-depressive score after the MBA treatment was significantly higher than those after the ALFX and MB treatments (P<0.001, each).

Fig. 1.

Median (± quartile deviation) total neuro-depressive scores in 6 dogs before (Baseline) and after the intramuscular (IM) treatments. Based on responsiveness expressed by the dogs, the categories of a composite measure scoring system were rated in scores 0 to 2 for jaw relaxation, 0 to 3 for placement of side, general attitude and toe-pinch response, or 0 to 4 for spontaneous posture and response to noise [30]. Total neuro-depressive score was calculated as a sum of scores in these 6 categories. ALFX: alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg administered IM. MB: medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg coadministered IM. MBA: alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg, medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg coadministered IM. †Significant difference from the ALFX group (P<0.05). ‡Significant difference from the MB group (P<0.05).

The quality of recovery after IM treatments is shown in Table 2. The quality of recovery score did not differ between treatments (P=0.747). During the recovery period, ataxia was observed in 2 dogs (33%), one dog (17%) and 3 dogs (50%) receiving the ALFX, MB and MBA treatments, respectively. Transient muscular tremors or twitching was observed in 2 dogs (33%), 2 dogs (33%) and 5 dogs (83%) receiving the ALFX, MB and MBA treatments, respectively. Pronounced limb extension was also observed in one dog (17%) receiving the ALFX treatment, and vocalization or struggling was observed in one dog (17%) each administered the ALFX, MB and MBA treatments.

Changes in cardiorespiratory valuables: Changes in cardiorespiratory variables are summarized in Table 3. The RTs after the MBA treatment gradually decreased from baseline (P<0.001). Clinically relevant bradycardia (HR <60 beats/min) was observed in 4 dogs (67%) each receiving the MB and MBA treatments. The HRs after the MB and MBA treatments were significantly lower than those after the ALFX treatment (P<0.001, each). There were no significant differences for the SABP, DABP and MABP between the IM treatment groups, and clinically relevant hypotension (MABP <60 mmHg) was not observed during the present study. The CVPs after the MB and MBA treatments were significant higher than those after the ALFX treatment (P<0.001, each). The RR decreased from baseline after the MB and MBA treatments (P<0.001 and P=0.026) and were also significantly lower than that in the ALFX treatment. The PaCO2 was maintained within normal range, although statistical differences were detected in the MB and MBA treatments compared with ALFX treatment (P=0.006 and P<0.001). Spontaneous breathing was maintained, and clinical relevant hypoxemia (PaO2 <60 mmHg or SaO2 <90%) was not detected in all treatment groups. The pHa after the MB and MBA treatments was significantly lower compared to the ALFX treatment (P=0.002 and P<0.001). The ScvO2 after the MB and MBA treatments was lower compared to the ALFX treatment (P<0.001, each). The HCO3, B.E. and Lac after each treatment were maintained between the reference ranges for dogs [10, 11].

Table 3. Cardiorespiratory variables before and after each intramuscular (IM) treatment in dogs.

| Minutes after each IM treatments |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 90 | 120 | ||

| RT (°C) | ALFXc) | 37.6 ± 0.2 | 37.7 ± 0.2 | 37.6 ± 0.3 | 37.5 ± 0.4 | 37.4 ± 0.4 | 37.4 ± 0.4 | 37.3 ± 0.4 | 37.3 ± 0.4 | 37.4 ± 0.4 | 37.6 ± 0.6 | 37.6 ± 0.5 |

| MB | 37.9 ± 0.6 | 37.9 ± 0.3 | 37.9 ± 0.3 | 37.9 ± 0.4 | 37.8 ± 0.4 | 37.7 ± 0.4 | 37.5 ± 0.5 | 37.4 ± 0.6 | 37.3 ± 0.6 | 37.5 ± 0.4 | 37.5 ± 0.4 | |

| MBAc) | 38.0 ± 0.4 | 37.8 ± 0.3 | 37.8 ± 0.3 | 37.7 ± 0.2 | 37.6 ± 0.2 | 37.5 ± 0.2 | 37.3 ± 0.2 | 37.1 ± 0.2a) | 36.8 ± 0.3a) | 36.6 ± 0.7a) | 36.9 ± 1.1a) | |

| HR (beats/min) | ALFX | 99 ± 18 | 102 ± 18 | 99 ± 21 | 119 ± 12 | 121 ± 10 | 118 ± 15 | 103 ± 17 | 98 ± 33 | 101 ± 44 | 91 ± 24 | 79 ± 21 |

| MBb) | 108 ± 2 | 82 ± 13 | 71 ± 17 | 66 ± 10a) | 65 ± 18a) | 62 ± 13a) | 62 ± 14a) | 66 ± 17a) | 62 ± 18a) | 69 ± 21 | 66 ± 11a) | |

| MBAb) | 104 ± 19 | 97 ± 51 | 61 ± 13a) | 63 ± 15a) | 60 ± 13a) | 64 ± 15a) | 58 ± 17a) | 60 ± 18a) | 64 ± 14a) | 75 ± 23 | 77 ± 16 | |

| RR (breaths/min) | ALFX | 29 ± 5 | 33 ± 11 | 28 ± 8 | 28 ± 10 | 25 ± 13 | 21 ± 6 | 20 ± 4 | 24 ± 8 | 26 ± 17 | 29 ± 21 | 22 ± 5 |

| MBb) | 46 ± 46 | 17 ± 4a) | 15 ± 3a) | 14 ± 4a) | 14 ± 4a) | 15 ± 3a) | 12 ± 3a) | 12 ± 2a) | 11 ± 3a) | 12 ± 3a) | 13 ± 2a) | |

| MBAb) | 36 ± 8 | 22 ± 6 | 22 ± 5 | 21 ± 4 | 18 ± 6 | 16 ± 5 | 14 ± 3a) | 15 ± 5 | 15 ± 4a) | 14 ± 5a) | 14 ± 3a) | |

| SABP (mmHg) | ALFX | 186 ± 24 | 170 ± 27 | 166 ± 24 | 160 ± 21 | 151 ± 22 | 158 ± 18 | 156 ± 19 | 160 ± 21 | 165 ± 28 | 171 ± 23 | 159 ± 37 |

| MB | 192 ± 28 | 192 ± 18 | 179 ± 20 | 167 ± 24 | 162 ± 20 | 155 ± 19 | 151 ± 18 | 149 ± 16a) | 145 ± 17a) | 158 ± 19 | 166 ± 20 | |

| MBA | 186 ± 15 | 176 ± 17 | 183 ± 21 | 159 ± 26 | 153 ± 14 | 149 ± 12 | 148 ± 12 | 145 ± 9 | 139 ± 13a) | 135 ± 10a) | 154 ± 29 | |

| MABP (mmHg) | ALFX | 108 ± 14 | 99 ± 15 | 96 ± 11 | 100 ± 11 | 97 ± 13 | 99 ± 14 | 97 ± 10 | 98 ± 13 | 97 ± 11 | 101 ± 14 | 102 ± 21 |

| MB | 118 ± 18 | 120 ± 13 | 105 ± 13 | 99 ± 13 | 98 ± 15 | 92 ± 9 | 87 ± 11a) | 85 ± 7a) | 87 ± 8a) | 99 ± 10 | 99 ± 7 | |

| MBA | 111 ± 8 | 117 ± 20 | 112 ± 23 | 100 ± 19 | 99 ± 16 | 94 ± 13 | 88 ± 8 | 86 ± 11 | 86 ± 8 | 90 ± 13 | 96 ± 16 | |

| DABP (mmHg) | ALFX | 82 ± 10 | 75 ± 10 | 73 ± 8 | 79 ± 10 | 77 ± 9 | 78 ± 14 | 76 ± 8 | 77 ± 12 | 76 ± 8 | 72 ± 8 | 72 ± 11 |

| MB | 89 ± 13 | 92 ± 10 | 78 ± 9 | 76 ± 9 | 77 ± 12 | 70 ± 6 | 67 ± 9a) | 65 ± 5a) | 68 ± 7a) | 76 ± 7 | 75 ± 7 | |

| MBA | 81 ± 3 | 89 ± 16 | 87 ± 21 | 77 ± 16 | 77 ± 14 | 70 ± 10 | 68 ± 8 | 66 ± 11 | 65 ± 7 | 69 ± 12 | 75 ± 14 | |

| CVP (mmHg) | ALFX | 2 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 3 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 0 | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 |

| MBb) | 3 ± 2 | 3 ± 2 | 5 ± 4 | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | |

| MBAb) | 4 ± 6 | 3 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 | 6 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | |

| pHa | ALFX | 7.39 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.02 | 7.38 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.01 | 7.36 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.02 | 7.38 ± 0.03 | 7.38 ± 0.02 | 7.39 ± 0.02 |

| MBb) | 7.39 ± 0.02 | 7.39 ± 0.03 | 7.37 ± 0.04 | 7.35 ± 0.02a) | 7.35 ± 0.02a) | 7.35 ± 0.02a) | 7.34 ± 0.02a) | 7.36 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.02 | 7.38 ± 0.03 | |

| MBAb,c) | 7.38 ± 0.01 | 7.36 ± 0.02 | 7.35 ± 0.02 | 7.34 ± 0.01a) | 7.33 ± 0.01a) | 7.33 ± 0.01a) | 7.34 ± 0.01 | 7.35 ± 0.01 | 7.35 ± 0.02 | 7.36 ± 0.02 | 7.35 ± 0.02b) | |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | ALFX | 95 ± 8 | 89 ± 6 | 92 ± 8 | 91 ± 13 | 88 ± 10 | 88 ± 12 | 91 ± 8 | 96 ± 10 | 98 ± 8 | 99 ± 12 | 98 ± 7 |

| MB | 101 ± 8 | 95 ± 5 | 93 ± 6 | 93 ± 7 | 93 ± 8 | 96 ± 12 | 89 ± 6 | 92 ± 4 | 92 ± 5 | 96 ± 6 | 96 ± 4 | |

| MBAc) | 100 ± 8 | 92 ± 6 | 88 ± 6 | 89 ± 8 | 90 ± 7 | 91 ± 5 | 90 ± 6 | 90 ± 5 | 88 ± 7 | 88 ± 10 | 87 ± 4 | |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | ALFX | 39 ± 4 | 40 ± 4 | 40 ± 4 | 39 ± 5 | 40 ± 5 | 41 ± 3 | 41 ± 4 | 40 ± 5 | 39 ± 4 | 38 ± 4 | 36 ± 4 |

| MBb) | 39 ± 2 | 39 ± 2 | 40 ± 3 | 43 ± 3 | 43 ± 3 | 43 ± 3 | 43 ± 3 | 42 ± 2 | 42 ± 3 | 41 ± 2 | 41 ± 3 | |

| MBAb) | 39 ± 3 | 41 ± 2 | 42 ± 2 | 43 ± 3 | 43 ± 2 | 42 ± 3 | 43 ± 4 | 43 ± 3 | 43 ± 3 | 43 ± 3 | 44 ± 2 | |

| HCO3 (mmol/l) | ALFX | 23.5 ± 3.2 | 23.4 ± 2.7 | 22.9 ± 2.6 | 23.1 ± 3.0 | 23.2 ± 2.9 | 23.5 ± 2.6 | 23.1 ± 3.1 | 23.0 ± 3.1 | 22.9 ± 3.1 | 22.4 ± 2.3 | 21.9 ± 3.0 |

| MB | 23.6 ± 1.3 | 23.0 ± 1.3 | 22.8 ± 1.0 | 23.3 ± 1.3 | 23.2 ± 1.3 | 23.2 ± 1.2 | 23.6 ± 1.6 | 23.7 ± 1.4 | 23.7 ± 1.7 | 23.3 ± 1.0 | 23.8 ± 1.0 | |

| MBA | 23.8 ± 1.9 | 23.1 ± 1.8 | 23.1 ± 1.8 | 22.9 ± 1.9 | 22.5 ± 1.8 | 22.3 ± 1.8 | 22.8 ± 1.8 | 23.3 ± 1.4 | 23.7 ± 1.3 | 24.3 ± 1.3 | 24.5 ± 1.2 | |

| B.E. (mmol/l) | ALFX | –1.1 ± 2.9 | –1.5 ± 2.4 | –2.0 ± 2.3 | –1.7 ± 2.4 | –1.7 ± 2.5 | –1.7 ± 2.5 | –2.1 ± 2.8 | –2.0 ± 2.7 | –2.0 ± 3.0 | –2.1 ± 2.2 | –2.4 ± 2.7 |

| MB | –0.9 ± 1.2 | –1.4 ± 1.3 | –2.1 ± 1.4 | –2.1 ± 1.2 | –2.1 ± 1.2 | –2.2 ± 1.0 | –2.1 ± 1.4 | –1.6 ± 1.4 | –1.6 ± 1.7 | –1.8 ± 1.0 | –1.2 ± 1.5 | |

| MBA | –0.9 ± 1.7 | –2.0 ± 1.9 | –2.2 ± 1.8 | –2.7 ± 1.8 | –3.2 ± 1.8 | –3.3 ± 1.6 | –2.8 ± 1.5 | –2.3 ± 1.1 | –2.1 ± 1.1 | –1.4 ± 1.3 | –1.3 ± 1.3 | |

| SaO2 (%) | ALFX | 97 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 2 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 2 | 96 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 |

| MB | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 0 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 1 | |

| MBAb) | 97 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 0 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 1 | 96 ± 2 | 96 ± 0 | |

| ScvO2 (%) | ALFX | 74 ± 6 | 76 ± 6 | 83 ± 4 | 85 ± 2 | 84 ± 5 | 82 ± 9 | 83 ± 4 | 81 ± 8 | 78 ± 8 | 73 ± 6 | 72 ± 5 |

| MBb) | 78 ± 8 | 66 ± 10 | 65 ± 5a) | 69 ± 4 | 70 ± 7 | 73 ± 4 | 76 ± 6 | 77 ± 4 | 78 ± 5 | 66 ± 6 | 72 ± 5 | |

| MBAb) | 76 ± 9 | 70 ± 5 | 68 ± 6 | 67 ± 6 | 74 ± 7 | 72 ± 7 | 72 ± 7 | 69 ± 7 | 71 ± 9 | 68 ± 11 | 73 ± 10 | |

| Lac (mmol/l) | ALFXc) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| MB | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3a) | 1.0 ± 0.2a) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2a) | |

| MBAc) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | |

Data are expessed as mean ± standard deviation. RT: rectal tempareture, HR: heart rate, RR: respiratory rate, SABP: systolic arterial blood pressure, MABP: mean arterial blood pressure, DABP: diastolic arterial blood pressure, CVP: central venous pressure, pHa: arterial pH, PaO2: partial pressure of arterial oxygen, PaCO2: partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide, HCO3: arterial bicarbonate concentration, B.E.: arterial base excess, SaO2: arterial oxygen saturation, ScvO2: central venous oxygen saturation, Lac: arterial plasma lactate concentration. ALFX: alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg administered IM. MB: medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg coadministered IM. MBA: alfaxalone 2.5 mg/kg, medetomidine 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol 0.25 mg/kg coadministered IM. a) Significant difference from baseline value (P<0.05). b) Significant difference from the ALFX group (P<0.05). c) Significant difference from the MB group (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the simultaneous (i.e. mixed in the same syringe) IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD (2.5 mg/kg), medetomidine (2.5 µg/kg) and butorphanol (0.25 mg/kg) provided an anesthetic effect allowing the endotracheal intubation without severe cardiorespiratory depression in healthy dogs.

Medetomidine induces marked peripheral vasoconstriction and cardiovascular depression when administered its recommended label dose (20 µg/kg IV or 40 µg/kg IM) in dogs [22, 27]. Pypendop et al. [22] reported that lower doses of medetomidine (1 and 2 µg/kg IV) produced less cardiovascular depression in dogs. On the other hand, low doses of medetomidine (2 or 5 µg/kg IM) provided minimum sedation without analgesia [20]. Butorphanol (0.25 mg/kg IM) provides moderate analgesia with minimum sedation for only 2 to 3 hr based on its rapid clearance [15, 21]. Girard et al. [5] reported that the combination of low dose medetomidine and butorphanol produced synergic sedative effects. It was reported that the anesthetic induction doses of IV alfaxalone-HPCD were 0.8 ± 0.3 mg/kg in dogs premedicated with medetomidine (4 µg/kg IM) and butorphanol (0.1 mg/kg IM) [16] and 2.6 ± 0.4 mg/kg in unpremedicated dogs [17]. Recently, we reported that the IM doses of alfaxalone-HPCD alone at 7.5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg provided reliable induction of anesthesia in dogs [28]. As we expected, the anesthetic induction dose of IM alfaxalone-HPCD could be reduced by the co-administration of low dose of medetomidine and butorphanol. According to the guideline by the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries Associations and the European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods, the IM volume considered as good practice is 0.25 ml/kg, and the maximal dose volume is 0.5 ml/kg in dogs [3]. The IM volume of the MBA treatment was 0.3 ml/kg and was accepted and completed without resisting it in all dogs under manual physical restraint. In addition, no pathological changes around the injection sites were observed after the MBA treatment. Our result suggests that the IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD at 2.5 mg/kg combined with medetomidine at 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol at 0.25 mg/kg can produce anesthetic effects allowing endotracheal intubation with a humane and clinically acceptable injection volume for dogs.

In the present study, the MBA treatment showed a larger variation of the time of onset of lateral recumbency than the ALFX treatment. In addition, the MBA treatment was slightly slower in onset of anesthesia compared with the ALFX treatment, although statistical analysis could not be performed. We reported that an IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD alone at 7.5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg produced anesthetic effects in dogs enabling to intubate at 8 ± 1 min and 10 ± 2 min, respectively [28]. The endotracheal intubation was achieved at 16 ± 6 min after the MBA treatment in the present study. From these findings, the MBA treatment seemed to be slightly slower in onset of anesthesia compared with those after IM alfaxalone-HPCD alone. It is possible that the α2-adrenoceptors agonists (e.g. dexmedetomidine which is the S-enantiomer of medetomidine) interfere with the absorption of the co-administered drug via vasoconstriction around the site of injection [29]. It was supposed that vasoconstriction produced by medetomidine might interfere with the absorption of alfaxalone-HPCD and resulted in slower onset of anesthetic effect with large variation of onset time in dogs receiving the MBA treatment.

Muir et al. [19] reported that an IV administration of alfaxalone-HPCD alone resulted in dose-dependent changes in cardiovascular and respiratory parameters in dogs breathing room air. An IV administration of alfaxalone-HPCD alone at 6 mg/kg produced hypoxia associated with hypoventilation mainly caused by a decrease in respiratory rate and transient apnea, although the cardiovascular status was well maintained [19]. Hypoxemia associated with a decrease in RR was observed in a dose-dependent manner following the IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD alone at 5, 7.5 and 10 mg/kg, while the cardiovascular status was well maintained [28]. In the present study, the RR decreased significantly from the baseline value after each IM treatment, but the RR and PaCO2 were maintained between the normal range for dogs under general anesthesia [24], and clinical relevant hypoxemia was not detected in any dog breathing room air. Kuo et al. [13] reported that IV administration of medetomidine at 20 µg/kg and butorphanol at 0.2 mg/kg caused a marked decrease in RR and mild hypoventilation without hypoxemia in dogs. Therefore, we considered that the decreased RR observed after the MB and MBA treatments was mainly due to the central nervous system depression produced by both α2-adrenoceptor [27] and opiate receptor ligand binding [26]. In conclusion, the simultaneous IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD (2.5 mg/kg), medetomidine (2.5 µg/kg) and butorphanol (0.25 mg/kg) produced an anesthetic effect with a mild respiratory depression in healthy dogs.

In the present study, clinically relevant bradycardia was observed in some dogs receiving the MB or MBA treatment, although clinically relevant hypotension (MABP <60 mmHg) was not observed in any dog. The CVPs after the MB or MBA treatment were significant higher than that after the ALFX treatment. Pypendop et al. [22] reported that medetomidine induced a dose-dependent cardiovascular depression including a transient hypertension, baroreceptor mediated bradycardia and decreased cardiac output followed by an initial peripheral vasoconstriction. In addition, Kuo et al. [13] reported that the sedation with medetomidine and butorphanol had similar cardiovascular effects to that of medetomidine alone. Thus, decreases in HR after the MB and MBA treatments were most likely caused by a baroreceptor mediated reflex response associated with the administration of medetomidine [13, 22]. Increases in CVP after the MB and MBA treatments may also be related to a decrease in venous capacitance and cardiac output mainly associated with the administration of medetomidine [13]. In the present study, the ScvO2 after the MB and MBA treatments was lower than that after the ALFX treatment. Decreased ScvO2 is commonly associated with increased tissue oxygen demand, decreased oxygen delivery or both [8]. Tissue oxygen demand in anesthetized or sleeping dogs is generally lower than that in awake dogs [18]. On the other hand, oxygen delivery decreases when cardiac output decreases, blood hemoglobin content can decrease (i.e. bleeding), or hypoxemia occurs. In the present study, bleeding and hypoxemia were not detected in any of the dogs. Therefore, we surmised that the lower ScvO2 after the MB and MBA treatments also reflected the decreased cardiac output followed by vasoconstriction produced by medetomidine. However, the fact that the arterial blood pressure, HCO3, B.E. and Lac remained within clinically acceptable ranges indicated that the tissue of our dogs received adequate oxygen throughout the anesthetic period. From these findings, the simultaneous IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD (2.5 mg/kg), medetomidine (2.5 µg/kg) and butorphanol (0.25 mg/kg) provides anesthetic effect without severe cardiovascular depression in healthy dogs. Nevertheless, the MBA treatment is not recommended for dogs with significant cardiac disease, because it may cause a decrease in cardiac output followed by marked vasoconstriction induced by medetomidine.

In our previous study using the same recovery score used in the present study, the recovery scores were judged as score 2 (moderately smooth) in all 6 dogs receiving IM alfaxalone-HPCD alone at 5, 7.5 and 10 mg/kg [28]. All dogs (100%) receiving IM alfaxalone-HPCD alone at 5, 7.5 and 10 mg/kg showed involuntary muscle tremors and a transient staggering gait [28]. In addition, pronounced limb extension was also observed in 4 dogs (67%), 3 dogs (50%) and 5 dogs (83%), and a transient paddling of the forelimbs was observed in 3 dogs (50%), 2 dogs (33%) and 3 dogs (50%) receiving the alfaxalone-HPCD alone at 5, 7.5 and 10 mg/kg, respectively [28]. The quality of recovery from the MBA treatment seemed to be better with less undesirable events, compared with that from the IM alfaxalone-HPCD alone [28]. It was reported that premedication with buprenorphine and acepromazine [9] or co-administration of dexmedetomidine [23] improved the quality of recovery from total intravenous anesthesia with alfaxalone-HPCD in dogs. These findings indicate that premedication or co-administration of sedative and analgesic drugs may improve the quality of recovery from alfaxalone-HPCD anesthesia. It may be concluded that the simultaneous IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD (2.5 mg/kg), medetomidine (2.5 µg/kg) and butorphanol (0.25 mg/kg) provided a good anesthesia with better quality of recovery. We surmise that the dose sparing effect on the anesthetic IM alfaxalone-HPCD by use of a combination of medetomidine and butorphanol may be related to less undesirable events during recovery.

However, the frequency of muscle tremors or twitching during recovery from the MBA treatment (83%) was higher compared with the MB (33%) and ALFX treatments (33%). Sinclair et al. [27] reported that involuntary muscle twitching occurs in some dogs following sedation with medetomidine. The higher frequency of muscular tremors or twitching during the recovery from the MBA treatment may be associated with both alfaxalone-HPCD and co-administered drugs (medetomidine and/or butorphanol). A further study will be necessary to determine the influence of simultaneously administered drugs on the quality of recovery from the IM alfaxalone-HPCD in dogs.

Vomiting is a well-known side effect of medetomidine in dogs [27]. In the present study, no dogs vomited, although nausea like behavior was observed in dogs receiving the MB and MBA treatments, respectively. It has been reported that butorphanol produced central antiemetic properties through the opioid receptor and effectively reduced vomiting induced by cisplatin [25] and medetomidine [7]. Although the mechanism of the interaction was not clear, we speculate that the co-administeration of butorphanol might prevent medetomidine-induced vomiting.

In the present study, the dogs showed deep sedation within 224 ± 110 sec and had laid in lateral recumbency for 46 ± 13 min after the IM treatment of alfaxalone-HPCD alone at 2.5 mg/kg. In addition, the ALFX treatment did not cause any cardiorespiratory depression in the dogs. We consider that the ALFX treatment may provide enough sedation and immobilization to complete less invasive procedures, such as securing vascular access or diagnostic imaging examination. However, there are some limitations when attempting to generalize the results of the present study to clinical practice because of the minimum sample size with the large distribution of age and body weight in the experimental animals used in the present study. In addition, all the animals were anesthetized with sevoflurane in oxygen for the catheter instrumentation before the each IM treatment. We cannot rule out the influence of the proceeded sevoflurane anesthesia on the anesthetic and cardiorespiratory effects of each IM treatment and the quality of recovery from each IM treatment. Other limitation of the present study is that plasma biochemistry was not performed before each treatment although there were no clinical symptoms of hypoactivitiy, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea and anemia in any of the dogs. In addition, it might be better to assess the neuro-depressive score by two observers. We are also concerned that mixing the drugs in the same syringe might affect each component. Chemical reactions including turbidity, precipitation or color changes were not observed before each administration in the present study.

In conclusion, the IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD at 2.5 mg/kg combined with medetomidine at 2.5 µg/kg and butorphanol at 0.25 mg/kg produced adequate anesthesia allowing endotracheal intubation without severe cardiorespiratory depression in healthy dogs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertson T. E., Walby W. F., Joy R. M.1992. Modification of GABA-mediated inhibition by various injectable anesthetics. Anesthesiology 77: 488–499. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199209000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burkholder W. J.2000. Use of body condition scores in clinical assessment of the provision of optimal nutrition. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 217: 650–654. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.217.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diehl K. H., Hull R., Morton D., Pfister R., Rabemampianina Y., Smith D., Vidal J. M., van de Vorstenbosch C., European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries Association and European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods. 2001. A good practice guide to the administration of substances and removal of blood, including routes and volumes. J. Appl. Toxicol. 21: 15–23. doi: 10.1002/jat.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferré P. J., Pasloske K., Whittem T., Ranasinghe M. G., Li Q., Lefebvre H. P.2006. Plasma pharmacokinetics of alfaxalone in dogs after an intravenous bolus of Alfaxan-CD RTU. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 33: 229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2005.00264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girard N. M., Leece E. A., Cardwell J., Adams V. J., Brearley J. C.2010. The sedative effects of low-dose medetomidine and butorphanol alone and in combination intravenously in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 37: 1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2009.00502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodchild C. S., Serrao J. M.1989. Cardiovascular effects of propofol in the anaesthetized dog. Br. J. Anaesth. 63: 87–92. doi: 10.1093/bja/63.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi K., Nishimura R., Yamaki A., Kim H., Matsunaga S., Sasaki N., Takeuchi A.1994. Comparison of sedative effects induced by medetomidine, medetomidine-midazolam and medetomidine-butorphanol in dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 56: 951–956. doi: 10.1292/jvms.56.951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes G. M., Mathews K., Boston S., Dewey C.2011. Low central venous oxygen saturation is associated with increased mortality in critically ill dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 52: 433–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbert G. L., Bowlt K. L., Ford-Fennah V., Covey-Crump G. L., Murrell J. C.2013. Alfaxalone for total intravenous anaesthesia in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy: a comparison of premedication with acepromazine or dexmedetomidine. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 40: 124–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2012.00752.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes D., Rozanski E. R., Shofer F. S., Laster L. L., Drobatz K. J.1999. Effect of sampling site, repeated sampling, pH, and PCO2 on plasma lactate concentration in healthy dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 60: 521–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilkiw J. E., Rose R. J., Martin I. C.1991. A comparison of simultaneously collected arterial, mixed venous, jugular venous and cephalic venous blood samples in the assessment of blood-gas and acid-base status in the dog. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 5: 294–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1991.tb03136.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keates H., Whittem T.2012. Effect of intravenous dose escalation with alfaxalone and propofol on occurrence of apnoea in the dog. Res. Vet. Sci. 93: 904–906. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo W. C., Keegan R. D.2004. Comparative cardiovascular, analgesic, and sedative effects of medetomidine, medetomidine-hydromorphone, and medetomidine-butorphanol in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 65: 931–937. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambert J. J., Belelli D., Peden D. R., Vardy A. W., Peters J. A.2003. Neurosteroid modulation of GABAA receptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 71: 67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamont L. A., Mathews K. A.2007. Opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and analgesic adjuvants. pp. 241–272. In: Lumb and Jones’ Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia, 4th ed. (Tranquilli, W. J., Thurmon, J. C. and Grimm, K. A. eds.), Blackwell Publishing, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maddern K., Adams V. J., Hill N. A., Leece E. A.2010. Alfaxalone induction dose following administration of medetomidine and butorphanol in the dog. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 37: 7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2009.00503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maney J. K., Shepard M. K., Braun C., Cremer J., Hofmeister E. H.2013. A comparison of cardiopulmonary and anesthetic effects of an induction dose of alfaxalone or propofol in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 40: 237–244. doi: 10.1111/vaa.12006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikat M., Peters J., Zindler M., Arndt J. O.1984. Whole body oxygen consumption in awake, sleeping, and anesthetized dogs. Anesthesiology 60: 220–227. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198403000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muir W., Lerche P., Wiese A., Nelson L., Pasloske K., Whittem T.2008. Cardiorespiratory and anesthetic effects of clinical and supraclinical doses of alfaxalone in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 35: 451–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2008.00406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muir W. W., 3rd, Ford J. L., Karpa G. E., Harrison E. E., Gadawski J. E.1999. Effects of intramuscular administration of low doses of medetomidine and medetomidine-butorphanol in middle-aged and old dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 215: 1116–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeffer M., Smyth R. D., Pittman K. A., Nardella P. A.1980. Pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous and intramuscular butorphanol in dogs. J. Pharm. Sci. 69: 801–803. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600690715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pypendop B. H., Verstegen J. P.1998. Hemodynamic effects of medetomidine in the dog: a dose titration study. Vet. Surg. 27: 612–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.1998.tb00539.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quirós Carmona S., Navarrete-Calvo R., Granados M. M., Domínguez J. M., Morgaz J., Fernández-Sarmiento J. A., Muñoz-Rascón P., Gómez-Villamandos R. J.2014. Cardiorespiratory and anaesthetic effects of two continuous rate infusions of dexmedetomidine in alfaxalone anaesthetized dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 97: 132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redondo J. I., Rubio M., Soler G., Serra I., Soler C., Gómez-Villamandos R. J.2007. Normal values and incidence of cardiorespiratory complications in dogs during general anaesthesia. A review of 1281 cases. J. Vet. Med. A Physiol. Pathol. Clin. Med. 54: 470–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.2007.00987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schurig J. E., Florczyk A. P., Rose W. C., Bradner W. T.1982. Antiemetic activity of butorphanol against cisplatin-induced emesis in ferrets and dogs. Cancer Treat. Rep. 66: 1831–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shook J. E., Watkins W. D., Camporesi E. M.1990. Differential roles of opioid receptors in respiration, respiratory disease, and opiate-induced respiratory depression. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 142: 895–909. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair M. D.2003. A review of the physiological effects of alpha2-agonists related to the clinical use of medetomidine in small animal practice. Can. Vet. J. 44: 885–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura J., Ishizuka T., Fukui S., Oyama N., Kawase K., Miyoshi K., Sano T., Pasloske K., Yamashita K.2015. The pharmacological effects of the anesthetic alfaxalone after intramuscular administration to dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 77: 289–296. doi: 10.1292/jvms.14-0368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshitomi T., Kohjitani A., Maeda S., Higuchi H., Shimada M., Miyawaki T.2008. Dexmedetomidine enhances the local anesthetic action of lidocaine via an alpha-2A adrenoceptor. Anesth. Analg. 107: 96–101. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318176be73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young L. E., Brearley J. C., Richards D. L. S., Bartram D. H., Jones R. S.1990. Medetomidine as a premedicant in dogs and its reversal by atipamezole. J. Small Anim. Pract. 31: 554–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1990.tb00685.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]