Abstract

Importance

Shared decision-making is associated with improved patient-reported outcomes, but not all patients prefer to participate in medical decisions. Studies of the effect of matching between actual and preferred medical decision roles on cancer patients’ perceptions of care quality have been conflicting.

Objective

To determine whether shared decision-making was associated with patient ratings of care quality and physician communication, and whether patients’ preferred decision roles modified those associations.

Design

We surveyed lung and colorectal cancer patients, diagnosed from 2003–2005, participating in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) study. We asked patients about their preferred roles in medical decisions and actual roles in decisions about surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. We assessed associations of patients’ decision roles with patient-reported quality of care and physician communication.

Setting

A population- and health-system-based cohort of lung and colorectal cancer patients, treated in integrated care delivery systems, academic institutions, private offices, and Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Participants

The CanCORS study included 9737 patients (cooperation rate among patients contacted, 59.9%). We analyzed 5315 patients (56% with colorectal, 40% with non-small cell lung, and 5% with small cell lung cancer) who completed baseline surveys and reported decision roles for a total of 10817 treatment decisions.

Main Outcome Measures

The outcomes (identified before data collection) included patient-reported “excellent” quality of care and top ratings (highest score) of physician communication scale.

Results

After adjustment, patients describing physician-controlled (versus shared) decisions were less likely to report excellent quality of care (odds ratio, OR=0.64, 95%CI=0.54–0.75; P<0.001); patients’ preferred decision roles did not modify this effect (P for interaction=0.29). Both actual and preferred physician-controlled (versus shared) roles were associated with lower ratings of physician communication (OR=0.55, 95%CI 0.45–0.66, P<0.001, and 0.67, 95%CI 0.51–0.87, P=0.002 respectively); preferred role did not modify the effect of actual role (P for interaction=0.76).

Conclusions and Relevance

Physician-controlled decisions regarding lung or colorectal cancer treatment were associated with lower ratings of care quality and physician communication. These effects were independent of patients’ preferred decision roles, underscoring the importance of seeking to involve all patients in decision-making about their treatment.

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine has called for shared decision-making and accommodation of patient preferences to improve overall health care quality,1 and in particular, the quality of cancer care.2 Prior studies of shared decision-making in cancer patients have found that most patients prefer to play a role in treatment decisions, but the degree to which their desired role matches their actual role in decision-making varies.3–5 Much of this work has focused on surgical decisions in breast cancer patients.4–6 Evidence suggests that patients who are younger, less educated, and who see higher-volume surgeons are less likely to have actual roles that match their preferred roles,5 and that patients whose preferred decision-making roles match their actual roles are more satisfied with their treatment choices.4,6 Nevertheless, one small study of patients with a variety of cancer types found that patients’ actual roles, but not matching between actual and preferred roles, were associated with satisfaction.7

Although their utility as metrics of quality is controversial, patients’ reports of their experiences with care are increasingly important healthcare performance measures.8,9 Indeed, the Affordable Care Act calls for the use of the patient experience Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey as a comparative measure of physician performance.9 It is possible that patients who are more actively engaged in their decisions, or whose roles match their preferred roles, may have better care experiences.

In a prior analysis, we examined the roles in decisions reported by patients in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study, a large, population- and health-system based study of lung and colorectal cancer patients. Among 10,939 treatment decisions made by 5383 patients, 39% were categorized as “patient-controlled,” 44% as “shared,” and 17% as “physician-controlled.”10 In the present study, we examined patients’ preferred roles in decisions to better understand the relative influence of preferred versus actual roles in decisions regarding surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Specifically, we assessed associations between patients’ actual roles in decisions and 1) patient-reported quality of care for each treatment modality (surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy) received, and 2) patient ratings of physician communication. In addition, because evidence suggests that there may be benefits to matching of actual to preferred roles,4,6 we assessed whether associations between actual role and patient-reported quality or physician communication ratings were modified by patients’ preferred roles in decision-making.

Methods

Study design and participants

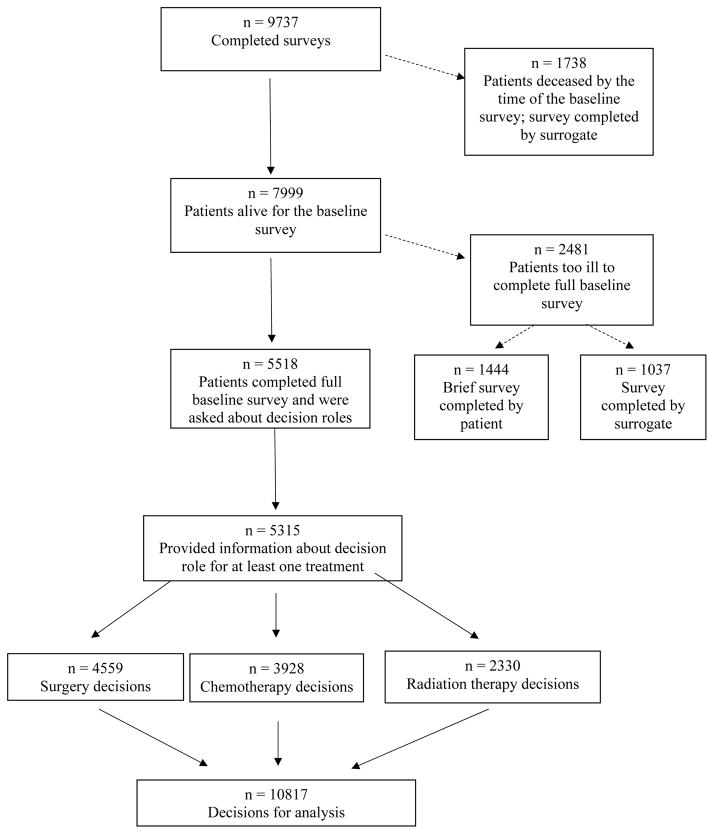

The CanCORS study investigated care processes, patient experiences with care, and outcomes among newly-diagnosed lung and colorectal patients living within one of five geographic regions (Northern California, Los Angeles County, North Carolina, Iowa, or Alabama) or receiving care in one of five health maintenance organizations or 15 Veterans Affairs sites.11 Cases were identified using rapid case ascertainment based on registry data.12,13 Patients (or surrogates if patients were too ill or deceased) were surveyed 3–6 months after diagnosis. The American Association for Public Opinion Research14 survey response rate was 51.0%; the cooperation rate was 59.9%.15 Additional details about patient eligibility have been described previously;15 the CanCORS cohort is representative of lung and colorectal cancer patients in the U.S.15 Information on cancer type, histology, and stage were obtained from registry data and medical records. We analyzed the subset of patients who were alive at the time of the baseline survey and completed a full baseline interview themselves (N=5518, Figure 1) and who answered questions about their preferred role in medical decisions in general, plus their actual role in decisions about one or more of the following: surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy (N=5315 patients). Characteristics of these patients, compared with respondents who completed surrogate survey versions or brief surveys, or did not answer questions about decision roles, are listed in Supplemental Table 1. The study was approved by human subjects committees at all participating institutions.

Figure 1.

Derivation of analysis cohort

Outcome variables

Patient-reported quality of care

Patients reported their perception of the overall quality of care for each treatment modality they received. Response options included “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair,” or “poor.” To facilitate presentation of results, responses were grouped into “excellent” versus all other responses, because most patients (67.8%) responded “excellent.”

Ratings of physician communication

As previously described,13,16 five questions related to physician communication was derived from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS)17 survey. The questions were “How often did your doctors 1) listen carefully to you?, 2) explain things in a way you could understand?, 3) give you as much information as you wanted about your cancer treatments, including potential benefits and side effects?, 4) encourage you to ask all the cancer-related questions you had?, and 5) treat you with courtesy and respect?” Response options were “always” (3 points), “usually” (2 points), “sometimes” (1 point), and “never” (0 points). We averaged these scores and grouped the results into 3 (“top rated physicians”, 55.8% of patients) versus <3. Patients rated their physicians as a group, rather than rating each physician separately.

Independent variables

Decision roles

We assessed patients’ overall preferred roles in decision-making for their cancer, and for each treatment modality considered (surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation), we also assessed the actual role they played in decision-making for that modality. Preferred and actual roles for decisions were ascertained using the five-item Control Preferences Scale.3,18,19 Response options for preferred roles were 1) “you prefer to make decisions about treatment with little or no input from your doctors,” 2) “you prefer to make the decisions after considering your doctor’s opinion,” 3) “you prefer that you and your doctors make the decisions together,” 4) “you prefer that your doctors make the decisions after considering your opinion,” and 5) “you prefer your doctors make the decision with little or no input from you.” Response options for the actual roles variable were 1) “you made the decision with little or no input from your doctors,” 2) “you made the decision after considering your doctors’ opinions,” 3) “you and your doctors made the decision together,” 4) “your doctors made the decision after considering your opinion,” and 5) “your doctors made the decision with little or no input from you.” In all analyses, actual and preferred roles were categorized as patient-controlled (responses 1 or 2), shared (response 3), or physician-controlled (responses 4 or 5), as described previously.5,10,20

Patient characteristics

Analyses adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, geographic region, income, enrollment in an integrated health care system (patients enrolled through the Veteran’s Affairs, Kaiser Permanente of Northern or Southern California, or other health maintenance organization sites), number of self-reported comorbid conditions,21–23 health status before diagnosis (which is associated with patient satisfaction;24 our measure included a subset of 5 questions from the Short-Form 12, and categorized in quartiles),25 and depression (positive response for ≥6 of the 8-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression, or CES-D, scale).26 We also adjusted for treatment modality, cancer type, and stage at diagnosis. The patient-reported quality outcome was assessed only among patients who reported receiving the treatment corresponding to each decision; for the analyses in which the outcome variable was ratings of physician communication, we also adjusted for whether patients reported receiving the treatment corresponding to each decision. Variables were categorized as in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics and unadjusted associations with patient-reported quality and ratings of physician communication

| No. of patients (%) | No. of decisions for group rating treatment quality† (%) | % reporting excellent treatment quality | P* | No. of decisions for group rating physician communication (%) | % reporting top rating | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | N=5315 | N=8191 (5170 patients) | 67.8% | N=4825 (4825 patients) | 55.8% | ||

| Preferred role | |||||||

| Patient-controlled | 1921 (36) | 2910 (36) | 67.0% | 0.13 | 1739 (36) | 55.6% | <0.001 |

| Shared | 3080 (58) | 4790 (59) | 68.6% | 2799 (58) | 57.3% | ||

| Physician-controlled | 314 (6) | 491 (6) | 64.0% | 287 (6) | 42.5% | ||

| Actual role | |||||||

| Patient-controlled | --- | 3262 (40) | 68.1% | <0.001 | 1914 (40) | 57.3% | <0.001 |

| Shared control | --- | 3855 (47) | 70.0% | 2264 (47) | 59.0% | ||

| Physician-controlled | --- | 1074 (13) | 58.5% | 647 (13) | 40.5% | ||

| Decision type | |||||||

| Surgery | --- | 3920 (48) | 67.9% | <0.001 | 3222 (67) | 58.4% | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | --- | 2991 (37) | 66.1% | 1603 (33) | 50.5% | ||

| Radiation | --- | 1280 (16) | 71.3% | --- | N/A‡ | ||

| Received treatment corresponding to decision† | |||||||

| No | --- | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A | 309 (6) | 53.1% | 0.32 |

| Yes | --- | 8191 (100) | 67.8% | 4516 (94) | 56.0% | ||

| Not ascertained | --- | 0 (0) | N/A | 0 (0) | N/A | ||

| Cancer type | |||||||

| Colorectal | 2958 (56) | 4767 (58) | 67.8% | 0.15 | 2754 (57) | 57.4% | 0.04 |

| Non-small cell lung | 2110 (40) | 3027 (37) | 67.0% | 1858 (39) | 53.8% | ||

| Small cell lung | 247 (5) | 397 (5) | 72.5% | 213 (4) | 53.1% | ||

| Stage at diagnosis | |||||||

| I | 1428 (27) | 1685 (21) | 70.2% | 0.002 | 1377 (29) | 60.1% | <0.001 |

| II | 1043 (20) | 1614 (20) | 68.1% | 1009 (21) | 57.8% | ||

| III | 1535 (29) | 2872 (35) | 68.7% | 1453 (30) | 53.1% | ||

| IV | 1058 (20) | 1653 (20) | 65.2% | 986 (20) | 51.8% | ||

| Unknown | 251 (5) | 367 (5) | 59.4% | 0 (0) | N/A | ||

| Age at diagnosis in years | |||||||

| < 54 | 1001 (19) | 1801 (22) | 66.1% | 0.002 | 928 (19) | 53.7% | 0.16 |

| 54–61 | 1111 (21) | 1854 (23) | 67.9% | 1041 (22) | 53.7% | ||

| 62–68 | 1098 (21) | 1745 (21) | 71.2% | 994 (21) | 58.1% | ||

| 69–75 | 1076 (20) | 1512 (18) | 69.0% | 964 (20) | 56.4% | ||

| >75 | 1029 (19) | 1279 (16) | 63.6% | 898 (19) | 57.4% | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 2835 (53) | 4443 (54) | 69.2% | 0.008 | 2592 (54) | 54.9% | 0.19 |

| Female | 2480 (47) | 3748 (46) | 66.0% | 2233 (46) | 56.8% | ||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 3704 (70) | 5633 (69) | 71.1% | <0.001 | 3375 (70) | 55.9% | <0.001 |

| African-American | 713 (13) | 1135 (14) | 63.0% | 627 (13) | 64.8% | ||

| Other | 898 (17) | 1423 (17) | 58.2% | 823 (17) | 48.5% | ||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married/partnered | 3298 (62) | 5179 (63) | 69.5% | <0.001 | 3029 (63) | 56.5% | 0.24 |

| Unmarried | 2014 (38) | 3012 (37) | 64.7% | 1796 (37) | 54.7% | ||

| Not ascertained | 3 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Education attained | |||||||

| Less than high school | 887 (17) | 1345 (16) | 62.2% | <0.001 | 786 (16) | 57.1% | 0.045 |

| High school graduate | 3101 (58) | 4788 (58) | 69.1% | 2805 (58) | 56.8% | ||

| College graduate | 1320 (25) | 2049 (25) | 68.4% | 1228 (25) | 52.8% | ||

| Missing data | 7 (0) | 9 (0) | 6 (0.1) | ||||

| Region | |||||||

| Northeast/Midwest | 714 (13) | 1090 (13) | 68.4% | <0.001 | 572 (12) | 59.8% | <0.001 |

| South | 1778 (33) | 2861 (35) | 70.9% | 1636 (34) | 62.0% | ||

| West | 2823 (53) | 4240 (52) | 65.5% | 2617 (54) | 51.1% | ||

| Income in last year | |||||||

| < $20,000 | 1415 (27) | 2122 (26) | 63.9% | <0.001 | 1266 (26) | 53.6% | 0.12 |

| $20,000–$40,000 | 1409 (27) | 2156 (26) | 68.1% | 1286 (27) | 58.3% | ||

| $40,000–$60,000 | 824 (16) | 1302 (16) | 70.4% | 760 (16) | 55.1% | ||

| > $60,000 | 1211 (23) | 1960 (24) | 72.9% | 1132 (23) | 56.2% | ||

| Unknown | 456 (9) | 651 (8) | 381 (8) | 54.9% | |||

| Integrated health system | |||||||

| No | 3492 (66) | 5419 (66) | 68.0% | 0.55 | 3197 (66) | 55.8% | 0.97 |

| Yes | 1823 (34) | 2772 (34) | 67.2% | 1628 (34) | 55.8% | ||

| Number of self-reported comorbid conditions | |||||||

| 0 | 2392 (45) | 3836 (47) | 67.5% | 0.17 | 2193 (45) | 57.8% | 0.08 |

| 1 | 1781 (34) | 2684 (33) | 67.1% | 1606 (33) | 54.7% | ||

| 2 | 760 (14) | 1138 (14) | 67.8% | 686 (14) | 53.8% | ||

| 3+ | 380 (7) | 533 (7) | 72.6% | 340 (7) | 52.7% | ||

| Not ascertained | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Pre-diagnosis health status (quartile) | |||||||

| 1 | 1304 (25) | 2046 (25) | 68.0% | <0.001 | 1161 (24) | 52.8% | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1341 (25) | 2060 (25) | 63.0% | 1222 (25) | 51.3% | ||

| 3 | 1177 (22) | 1841 (23) | 67.7% | 1075 (22) | 55.7% | ||

| 4 | 1386 (26) | 2100 (26) | 72.4% | 1274 (26) | 63.1% | ||

| Not ascertained | 107 (2) | 144 (2) | 93 (2) | ||||

| CES-D short form | |||||||

| <6 | 4266 (80) | 6474 (79) | 69.8% | <0.001 | 3881 (80) | 58.6% | <0.001 |

| ≥6 | 813 (15) | 1358 (17) | 60.3% | 738 (15) | 43.4% | ||

| Not ascertained | 236 (4) | 359 (4) | 206 (4) |

P for test of combined significance of the levels of each independent variable for prediction of the outcome, using bivariable logistic regression analysis. For the perceived quality outcome, we used a robust standard error estimate to account for repeated measures among individual patients.

Patients only reported quality of care corresponding to a treatment decision if they received the treatment under consideration for that decision.

Ratings of physician communication were analyzed when the decision role for a treatment corresponded to the most common type of treatment decision for patients with the same stage and cancer type. There were no clinical subgroups for whom the most common decision type was radiation therapy.

Statistical analysis

The 5315 patients in our cohort reported decision roles for 10817 treatment decisions (4559 surgery, 3928 chemotherapy, and 2330 radiation therapy decisions; Figure 1). For analyses of perceived quality of care for each treatment, these decisions constituted the unit of analysis, with one observation per decision. Each patient could have up to 3 observations if they participated in decisions about surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. There were 8201 decisions made by 5176 patients who received a treatment under consideration and rated overall quality of care for that treatment.

For analyses of physician communication, we included only one decision per patient, since patients provided overall ratings of communication with their physicians, rather than rating each treating physician. We identified the most frequently discussed treatment decision (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation) for each cancer type and stage to select the treatment for which we would include the actual decision role. Among patients with stage I–II NSCLC or stage I–III CRC, we included surgery decisions; for patients with stage III–IV NSCLC, SCLC, or stage IV CRC, we included chemotherapy decisions. There were N=4848 patients who made such decisions. We further restricted to the 4830 patients who answered at least three of the five questions about communication with their physicians. For patients who answered only 3 or 4 of the 5 items, we averaged their responses; we also performed sensitivity analyses in which multiple imputation was used to impute missing responses for the questions. Results were similar and are not presented.

In unadjusted analyses, we used bivariable logistic regression to assess the associations of decision roles and other clinical characteristics with excellent patient-reported quality and top ratings of physician communication. For the patient-reported quality outcome, we used a robust covariance estimator to adjust standard errors for repeated measures within patients. We report P values for tests of combined significance of the categorical independent variables.

We used multivariable logistic regression to assess the association of actual and preferred roles in decisions with (1) patient-reported quality of care for the treatment considered during each decision (with a robust covariance estimator to account for repeated measures within patients) and (2) top ratings of physician communication, adjusting for all patient characteristics described above. For each dependent variable, we examined models that included actual decision role and preferred decision role. We also examined models that included the interaction of actual and preferred role. Finally, we examined the effect of actual role in decision-making, stratified by preferred decision roles. We calculated adjusted probabilities of each outcome for particular roles variables by taking the mean of predicted probabilities generated by the model for each observation, allowing other covariates to retain values from the original data. In sensitivity analyses, we also used proportional odds models in which the patient-reported quality outcome ranged from 0–4 as per the original survey scale, and in which the physician communication rating was categorized into tertiles. We also conducted sensitivity analyses stratified by patient sex. Results of all sensitivity analyses were similar and are not presented.

No data were missing for our dependent variables, as per our cohort definitions. Missing data were infrequent for demographic and clinical factors (<10% nonresponse for all items, Table 1). For adjusted analyses, we used multiple imputation to impute missing data for our independent variables; we did not use imputed data for the decision roles variables, the primary independent variables of interest.27 For patient-reported quality, 10 of 8201 decisions were made by patients completing only partial versions of their surveys, for which data were not imputed for some control variables; these decisions were excluded from analysis, and the final analysis cohort for that outcome included 8191 decisions made by 5170 patients. Similarly, for ratings of physician communication, 5 of 4830 decisions were excluded from models due to non-imputed missing data for partially completed surveys, leaving a final analysis cohort of 4825 patient decisions. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.2) and Stata (version 13).

Results

Most of the 5315 patients (56%) had colorectal cancer; 40% had non-small cell lung cancer, and 5% had small cell lung cancer. Most (58%) of the patients preferred shared roles in decision-making about their cancer; 36% preferred patient-controlled decisions, and 6% preferred physician-controlled decisions. Other patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Patients in our cohort made 10817 treatment decisions; 42% regarding surgery, 36% chemotherapy, and 22% radiation therapy. Participants reported that their actual decision-making process was patient-controlled in 39% of decisions, shared in 44% of decisions, and physician-controlled in 17% of decisions.

For 67.8% of treatments received by patients, patients reported their care by the physician performing the treatment as excellent. In adjusted analyses examining preferred and actual roles in decisions, the interaction of preferred and actual role was not statistically significant (P=0.29), and only the main effects model is presented. Preferred role was not associated with ratings of quality, but patient reports that treatment decisions were physician-controlled (versus shared) were associated with lower odds of excellent patient-reported quality (OR=0.64, 95% CI=0.54–0.75, P<0.001) (Table 2). In models stratified by preferred role, the negative associations between physician-controlled (versus shared) decisions and patient-reported quality were evident regardless of preferred role (Table 2).

Table 2.

Decision roles vs patient-perceived quality of care for treatment discussed, adjusted*

| Preferred role | Actual role | N (%) | Adjusted % reporting excellent quality | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients* | 8191 (100) | 67.7% | |||

| Patient-controlled | 2910 (36) | 66.5% | 0.91 (0.81–1.03) | 0.15 | |

| Shared | 4790 (59) | 68.4% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 491 (6) | 68.1% | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 0.90 | |

| Patient-controlled | 3262 (40) | 68.4% | 0.95 (0.84–1.06) | 0.35 | |

| Shared | 3855 (47) | 69.5% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 1074 (13) | 59.7% | 0.64 (0.54–0.75) | < 0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Effect of Actual Role Stratified by Preferred Role | |||||

|

| |||||

| Patient-controlled | |||||

| Patient-controlled | 1813 (22) | 68.0% | 1.04 (0.85–1.27) | 0.70 | |

| Shared | 807 (10) | 67.2% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 290 (4) | 59.7% | 0.71 (0.53–0.96) | 0.03 | |

|

| |||||

| Shared control | |||||

| Patient-controlled | 1338 (16) | 68.6% | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) | 0.30 | |

| Shared | 2905 (35) | 70.2% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 547 (7) | 60.2% | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Physician-controlled | |||||

| Patient-controlled | 111 (1) | 65.0% | 0.56 (0.28–1.09) | 0.09 | |

| Shared | 143 (2) | 74.8% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 237 (3) | 56.8% | 0.36 (0.20–0.63) | <0.001 | |

P for interaction of actual and preferred role= 0.29, so only main effects are presented in the top box; stratified results are also presented. These multivariable logistic regression models also adjusted for all variables in Table 1 (except for whether patients received the treatment corresponding to each decision, since patients only rated quality of care for a treatment if they received that treatment).

Overall, 55.8% of patients gave their physicians the highest possible (or “top”) rating of communication. In adjusted analyses, the interaction of preferred and actual decision roles was not statistically significant (P=0.76), and we present only the main effects model (Table 3). Both preferred and actual decision roles were associated with top ratings. Patients who preferred physician-controlled versus shared decisions were less likely to give top ratings to their physicians (OR=0.67, 95% CI=0.51–0.87), as were patients who reported actually experiencing physician-controlled versus shared decisions (OR=0.55, 95% CI=0.45–0.66). In models stratified by preferred role, the association of actual physician-controlled decisions with lower ratings remained evident, although this finding did not reach statistical significance for the relatively small number of decisions made by patients preferring physician-controlled decisions (OR=0.61, 95% CI=0.33–1.13, P=0.12).

Table 3.

Patient ratings of physician communication*

| Preferred role | Actual role | N (%) | Adjusted % providing top rating | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients* | 4825 (100) | 55.8% | |||

| Patient-controlled | 1739 (36) | 55.3% | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) | 0.27 | |

| Shared | 2799 (58) | 57.0% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 287 (6) | 47.5% | 0.67 (0.51–0.87) | 0.002 | |

| Patient-controlled | 1914 (40) | 57.4% | 0.98 (0.86–1.11) | 0.75 | |

| Shared | 2264 (47) | 57.9% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 647 (13) | 43.7% | 0.55 (0.45–0.66) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Effect of Actual Role Stratified by Preferred Role | |||||

|

| |||||

| Patient-controlled | |||||

| Patient-controlled | 1067 (22) | 57.0% | 1.03 (0.83–1.29) | 0.78 | |

| Shared | 494 (10) | 56.2% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 178 (4) | 44.8% | 0.62 (0.43–0.89) | 0.009 | |

|

| |||||

| Shared control | |||||

| Patient-controlled | 785 (16) | 58.5% | 0.95 (0.80–1.14) | 0.60 | |

| Shared | 1674 (35) | 59.6% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 340 (7) | 43.3% | 0.50 (0.39–0.64) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Physician-controlled | |||||

| Patient-controlled | 62 (1) | 50.9% | 1.22 (0.58–2.57) | 0.59 | |

| Shared | 96 (2) | 46.4% | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Physician-controlled | 129 (3) | 35.6% | 0.61 (0.33–1.13) | 0.12 | |

P for interaction of preferred and actual role=0.76, so only main effects model is presented in the top box; stratified results are also presented. These multivariable logistic regression models also adjusted for all variables in Table 1.

Discussion

In this large, population- and health-system based cohort of patients with recently-diagnosed lung and colorectal cancer, we found that among patients receiving treatment under consideration, those reporting physician-controlled versus shared decisions were less likely to report excellent quality of care for that treatment. This effect was not modified by preferred role in treatment decision-making, implying that shared decision-making was associated with higher perceived quality, even for patients preferring less active roles in medical decisions. Of note, patients were only asked to report quality of care when they also reported receiving the treatment in question. Therefore, factors such as whether these patients were treated, or were eligible for treatment, could not have contributed to their perceptions of involvement in treatment decisions or of the quality of care resulting from the decisions.

Similarly, patients who reported physician-controlled decisions gave lower patient ratings of physician communication compared with those reporting shared decisions, and patients’ preferred role in decisions did not modify this effect. Interestingly, even after adjustment for actual decision role and whether patients received treatments under consideration, patients who expressed a preference for physician-controlled decisions were independently less likely to rate physician communication highly. The explanation for this counterintuitive finding is not obvious, especially since other recent work indicated higher levels of trust in physicians among patients preferring physician controlled decisions.28 These patients may have different overall attitudes towards health care providers, and further work is needed to understand how they approach decision-making throughout their treatment courses.

The Institute of Medicine highlighted the importance of engaged and well-informed patients, along with shared decision-making, as central to a high-quality cancer care delivery system.2 Patient ratings of their experiences are also playing increasingly important roles as performance metrics.8,9 Although some patients may prefer that physicians take a leading role in decision-making,3,29 other evidence suggests that patients also want information about their treatments and prefer to take part in decisions,30 and that patient preferences for involvement in decisions have increased over time.31 Our findings suggest that providing information and engaging colorectal and lung cancer patients in shared decisions is valuable, even for patients who express preferences for physicians to control the decision-making process. Notably, the lack of an effect of matching between actual and preferred roles differed from prior findings in breast cancer.4,6 This may reflect heterogeneity of the effect of roles matching across disease types, or temporal changes in attitudes or expectations about decision-making. In sensitivity analyses, we found no evidence of effect modification by sex.

Strengths of our analysis include the large, multiregional, and representative15 cohort of patients with recently diagnosed lung and colorectal cancer. Several limitations remain, however. First, data were collected 3–6 months after diagnosis, so reports of roles played in treatment decisions may in some cases have been ascertained several months after those decisions took place.10 Additionally, we asked patients for preferences regarding decision-making and for ranking of their physicians’ communication in general, not with regard to specific therapies, and it is possible that preferred roles may have varied by the treatment under consideration.30 It is also possible that patients’ impressions of their decision-making processes may have been most influenced by the provider who played the most prominent role in their care. As with any survey, our analysis was subject to non-response bias, although prior analysis of the CanCORS data demonstrated that the demographics of the cohort changed little as data collection proceeded from initial ascertainment to final enrollment,15 and the response rate was relatively high, particularly for a population-based survey. Still, our analysis focused on patients who were alive and healthy enough to complete a full baseline survey approximately 3–6 months after diagnosis. Our outcomes were subjective, patient-reported measures; nevertheless, we believe that cancer patients’ perceptions of care quality and communication with their physicians are important, and they are playing increasingly important roles in quality improvement efforts. We adjusted for many clinical and demographic characteristics in this analysis; however, as in any observational study, we cannot exclude the possibility that unmeasured confounders may in part explain the associations between patient decision roles and ratings of care quality or physician communication. Finally, some evidence suggests that patients’ descriptions of their preferred decision roles may vary according to the measurement scale used.31 We used the well-accepted Control Preferences Scale,3,18,19 but these results do not exclude the possibility that, for example, even patients who prefer to control treatment decisions might also want clear treatment recommendations from their physicians.

In conclusion, among newly diagnosed lung and colorectal cancer patients who made decisions about surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation, patients who experienced physician-controlled versus shared decision making were less likely to report excellent quality of care and top ratings of physician communication. These associations were similar regardless of patients’ preferred roles in decisions. Given the increasing emphasis on patient experiences and ratings in health care, these results highlight the benefits of promoting shared decision-making among all patients with cancer, even those who express preferences for less active roles.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the Statistical Coordinating Center (U01 CA093344) and the NCI-supported Primary Data Collection and Research Centers (Dana Farber Cancer Institute/Cancer Research Network U01 CA093332, Harvard Medical School/Northern California Cancer Center U01 CA093324, RAND/UCLA U01 CA093348, University of Alabama at Birmingham U01 CA093329, University of Iowa U01 CA093339, University of North Carolina U01 CA093326) and by a Department of Veteran’s Affairs grant to the Durham VA Medical Center CRS 02-164. Drs. Keating and Landrum were also supported by 1R01CA164021-01A1.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Previous presentation: Presented in part in abstract form at the 2014 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(9):941–50. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keating NL, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, Borbas C, Weeks JC. Treatment decision making in early-stage breast cancer: should surgeons match patients’ desired level of involvement? J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(6):1473–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawley ST, Lantz PM, Janz NK, et al. Factors associated with patient involvement in surgical treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(3):387–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lantz PM, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, et al. Satisfaction with surgery outcomes and the decision process in a population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(3):745–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gattellari M, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. Sharing decisions in cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(12):1865–78. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1211775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glickman SW, Schulman KA. The mis-measure of physician performance. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(10):782–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Arora NK, et al. Cancer patients’ roles in treatment decisions: do characteristics of the decision influence roles? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(28):4364–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):2992–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearson ML, Ganz PA, McGuigan K, Malin JR, Adams J, Kahn KL. The case identification challenge in measuring quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(21):4353–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Arora NK, et al. Patients’ experiences with care for lung cancer and colorectal cancer: findings from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4154–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 5. Lenexa; Kansas: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catalano PJ, Ayanian JZ, Weeks JC, et al. Representativeness of participants in the cancer care outcomes research and surveillance consortium relative to the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Med Care. 2013;51(2):e9–15. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ Expectations about Effects of Chemotherapy for Advanced Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(17):1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hays RD, Shaul JA, Williams VS, et al. Psychometric properties of the CAHPS 1.0 survey measures. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Med Care. 1999;37(3 Suppl):MS22–31. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, et al. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 1997;277(18):1485–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29(3):21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davison BJ, Degner LF. Feasibility of using a computer-assisted intervention to enhance the way women with breast cancer communicate with their physicians. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25(6):417–24. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malin JL, Ko C, Ayanian JZ, et al. Understanding cancer patients’ experience and outcomes: development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(8):837–48. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klabunde CN, Reeve BB, Harlan LC, Davis WW, Potosky AL. Do patients consistently report comorbid conditions over time?: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. Med Care. 2005;43(4):391–400. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156851.80900.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao H, Barber JP. The effect of perceived health status on patient satisfaction. Value Health. 2008;11(4):719–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11(2):139–48. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Landrum MB, Harrington DP, Catalano P. Multiple imputation in a large-scale complex survey: a practical guide. Stat Methods Med Res. 2010;19(6):653–70. doi: 10.1177/0962280208101273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chawla N, Arora NK. Why do some patients prefer to leave decisions up to the doctor: lack of self-efficacy or a matter of trust? J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(4):592–601. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arora NK, McHorney CA. Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Med Care. 2000;38(3):335–41. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(13):1414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen Ja, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]