Abstract

Summary: The accurate reconstruction of gene regulatory networks from large scale molecular profile datasets represents one of the grand challenges of Systems Biology. The Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks (ARACNe) represents one of the most effective tools to accomplish this goal. However, the initial Fixed Bandwidth (FB) implementation is both inefficient and unable to deal with sample sets providing largely uneven coverage of the probability density space. Here, we present a completely new implementation of the algorithm, based on an Adaptive Partitioning strategy (AP) for estimating the Mutual Information. The new AP implementation (ARACNe-AP) achieves a dramatic improvement in computational performance (200× on average) over the previous methodology, while preserving the Mutual Information estimator and the Network inference accuracy of the original algorithm. Given that the previous version of ARACNe is extremely demanding, the new version of the algorithm will allow even researchers with modest computational resources to build complex regulatory networks from hundreds of gene expression profiles.

Availability and Implementation: A JAVA cross-platform command line executable of ARACNe, together with all source code and a detailed usage guide are freely available on Sourceforge (http://sourceforge.net/projects/aracne-ap). JAVA version 8 or higher is required.

Contact: califano@c2b2.columbia.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

We and others have shown that the accurate and systematic dissection of tissue gene regulatory networks (reverse engineering) represents a crucial step in the elucidation of drivers and mechanisms presiding over both physiologic and pathologic phenotypes. Many computational approaches have been proposed for the reverse engineering of gene regulatory networks from large-scale gene expression profile data. Most of these require estimating pairwise gene functions, such as Pearson/Spearman correlation (Mutwil et al., 2011), Mutual Information (MI, Steuer et al., 2002) and linear/LASSO regression (Licausi et al., 2011) amongst others. ARACNe (Margolin et al., 2006) represents one of the most widely used reverse engineering algorithms by the scientific community and has been extensively experimentally validated. ARACNe uses an information theoretic framework, based on the data processing inequality theorem, to infer direct regulatory relationships between transcriptional regulator proteins and target genes. ARACNe has been shown to be useful in the reconstruction of context-specific transcriptional networks in multiple tissue types (Lefebvre et al., 2010). Several additional algorithms have emerged, which rely on the interrogation of ARACNe networks to successfully predict novel driver genes and mechanisms (Aytes et al., 2014; Della Gatta et al., 2012), as well as drug mechanism of action (Woo et al., 2015). Thanks to the Next-Generation Sequencing revolution, however, ever expanding RNASeq datasets create the need for algorithm improvements to support more computationally efficient inference of genome-wide gene-regulatory networks. We introduce a complete redesign of ARACNe to leverage efficient Adaptive Partitioning (AP) Mutual Information estimators (Liang and Wang, 2008). We benchmark the performance improvements of the new algorithm implementation on the analysis of a large breast carcinoma dataset (TCGA, 2012), compared to the previous version of ARACNe, based on the Fixed Bandwidth (FB) algorithm (Margolin et al., 2006).

2 Methods

2.1 The ARACNe pipeline

We replaced the core FB MI-estimator with a new AP-based version and wrote an optimized implementation through a series of cached binning operations and the use of 16-bit short integers to store rank-transformed gene expression data. All performance sensitive parts of the algorithm, including the Data Processing Inequality (DPI) implementation, now support multi-threading, thus taking advantage of available computer architectures.

Additionally, while the original ARACNe implementation relied on a multiple Matlab scripts for pre and post processing while the core algorithm was implemented in C ++. The new version is streamlined and entirely implemented in a single JAVA executable removing the need for proprietary software and allowing for platform-independent use. ARACNe requires Gene Expression Profile (GEP) data and a predefined list of gene regulators (e.g. Transcription Factors – TFs) as input. Running ARACNe involves three key steps.

MI threshold estimation. This preprocessing step identifies a significance threshold of MI values from the GEPs provided. The threshold depends on the number of samples provided in the input.

Bootstrapping/MI network reconstruction. In this phase MI networks are reconstructed for randomly sampled GEP. For N such bootstraps of the data N MI networks are generated. The calculation of the networks involves three steps: (a) Compute MI for every TF/Target pair after rank-transformation of the GEPs. (b) Removal of non-statistically significant connections using the MI threshold. (c) Removal of indirect interactions by applying a Data Processing Inequality tolerance filter (DPI, Margolin et al., 2006).

Building consensus network. A consensus network is computed by estimating the statistical significance of the number of times a specific edge is detected across all bootstrap runs, based on a Poisson distribution. Only significant pairs are kept (P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected).

2.2 Adaptive partitioning

The Mutual Information between two variables is probabilistic measure of their statistical dependence (Steuer et al., 2002). Computing the MI from gene expression profiles usually requires estimating joint and marginal gene expression probability densities. In the original ARACNe implementation (FB), this was achieved by dividing the gene expression space into discrete bins of fixed size.

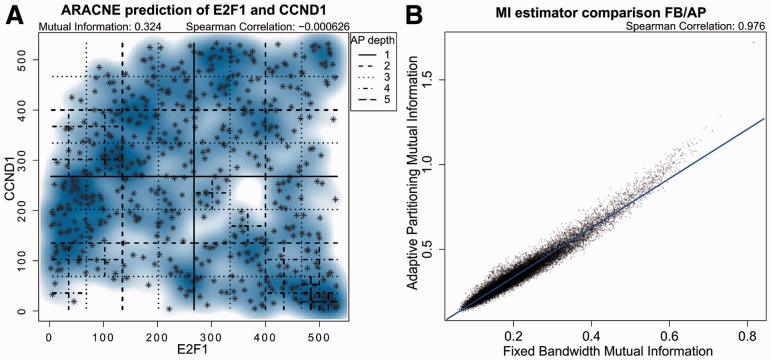

The original ARACNe algorithm was based on the FB MI-estimator, which generated equisized bins (Margolin et al., 2006). The number of bins selected for the analysis depended on the number of samples and had to be chosen in a preprocessing step. To address these limitations, we introduced an alternative AP-estimator. The two dimensional space are still divided into discrete bins but, in contrast to the FB algorithm, there is not a preset data-driven partition size. Rather, the space is divided in an adaptive fashion following the local data distribution. The space is split recursively into quadrants at the means (Fig. 1A). The stopping condition for the recursive procedure is met when a uniform distribution (assessed by χ2 test) between the newly created quadrants is reached or fewer than three data points fall into the quadrant to be split.

Fig. 1.

(A) Expression values of E2F1 and CCND1 in the TCGA breast carcinoma dataset. Shown are the binning steps of the Adaptive Partitioning to infer pairwise Mutual Information. (B) Comparison between FB-inferred (x-axis) and AP-inferred (y-axis) MI values for all TF/gene pairs in the breast cancer dataset

2.3 Datasets/hardware

In order to test the performance of ARACNEe-AP in terms of speed and qualitative MI assessment, we ran multiple benchmarks. We compared computational speed and tested the impact of the AP estimation of the joint density distribution compared to FB using 533 TCGA Breast invasive carcinoma samples (TCGA, 2012). The transcript raw counts were RPKM transformed and filtered for genes with zero counts leaving 13 812 genes. As regulators we used 1331 genes annotated as ‘regulators of transcription’ and ‘DNA-binding’ in Gene Ontology (GO, 2013). We calculate all pairwise MIs between 20 318 genes and express the speed as MIs per second. All the tests shown were performed on a multi-core Intel Xeon E5-2630 CPU.

3 Results and discussion

We ran ARACNe-AP on the TCGA Breast invasive carcinoma dataset, obtaining a network with 1331 regulators, 13 546 targets and 100 580 interactions. ARACNe-AP maintains the capability to identify regulator-target relationships that would be otherwise missed by simple correlation techniques or other linear similarity measures (Supplementary Fig. S1), e.g. that between E2F1 and CCND1 (Cyclin D1) (Fig. 1A), a ChIP-Seq validated interaction (Lachmann et al., 2010) that controls cell cycle progression (Sherr, 1994). The example of E2F1 regulating CCND1 highlights the advantage of non-linear measures such as MI to identify complex gene interactions. Indeed, Pearson correlation between E2F1 and CCND1 is close to 0 and not statistically significant (P = 0.4) while the MI is highly significant (P = 10 − 8). The data shows two sets of statistically independent relationships between these two genes. A subset of the samples supports a positive correlation recapitulating that E2F1 can promote its transcription indirectly, through Ras pathway activation (Berkovich et al., 2003), which in turn up-regulates Cyclin D1 mRNA synthesis (Croft and Olson, 2006). The negatively correlated samples support the fact that E2F1 can directly inhibit the transcription of Cyclin D1 (Watanabe et al., 1998).

Both the FB and the AP estimators achieve similar accuracy in the estimation of gene pairs MI. While the absolute MI values of the two methods are not directly comparable, the AP algorithm ranks gene pairs (based on their MI) similarly to the FB algorithm (Fig. 1B). Networks obtained with ARACNe-AP can be used to calculate regulator activity on a sample-by-sample basis using the ssMARINA algorithm (Aytes et al., 2014). The networks obtained via the FB and AP methods produce nearly identical inferences of regulatory protein activity, based on the differential expression of their regulons (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, the AP version of ARACNe provides a 200× gain in computational efficiency, thus greatly reducing execution time. Specifically, the optimized AP implementation (ARACNe-AP) can process an average of 31 610 MI/s, compared to only 160 with the original ARACNe implementation (ARACNe-FB) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Furthermore, ARACNe-AP is fully multi-threaded, yielding an additional speed increase on typical CPUs proportional to the number of available cores. A mainstream multithreaded CPU can process almost 200 000 gene-pair MI/s (Supplementary Fig. S5). ARACNe-AP is also more efficient (2× on average) in terms of memory usage, compared to ARACNe-FB, due to optimization and use of 16-bit short integers to store rank-transformed gene expression values, allowing the processing of datasets up to 65 536 samples (Supplementary Fig. S3). In conclusion, ARACNe-AP is more than two orders of magnitude faster than the previous ARACNe-FB implementation, while requiring only 50% of the memory. Among others, the ARACNe-AP implementation has been successfully applied to reverse engineering a T-ALL context specific transcriptional network which has resulted in elucidating RUNX1 as a tumor suppressor gene in this cancer (Della Gatta et al., 2012), and to reverse engineering a prostate cancer specific network leading to identification of FOXM1 and CENPF as synergistic Master Regulators of aggressive disease (Aytes et al., 2014).

Networks inferred by the improved algorithm are virtually identical to those inferred by the original one, both in terms of pairwise MI inference and overall network topology. Yet, the improvements provided by the new implementation have critical repercussions in the field of gene network analyses, as they allow the reconstruction of gene networks from datasets with up to 500 samples in less than one hour. Thus, a 100-bootstrap ARACNe analysis can be run on a standard desktop computer without the need for specialized supercomputers. In contrast, a 100-bootstrap run of ARACNe-FB would require a minimum of 100 supercomputing cores to be completed in a comparable amount of time, thus requiring expensive computational infrastructure not available to the majority of researchers. Finally, removal of proprietary Matlab code and consolidation of the algorithm into a single, platform-independent Java executable significantly increases ease of use and deployment

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work is supported by National Cancer Institute CTD2 network 5U01CA168426, National Cancer Institute MAGNet U54CA121852 and Leidos Biomedical Research Inc contract 15X036.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Aytes A. et al. (2014) Cross-species regulatory network analysis identifies a synergistic interaction between foxm1 and cenpf that drives prostate cancer malignancy. Cancer Cell, 25, 638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovich E. et al. (2003) E2f and ras synergize in transcriptionally activating p14arf expression. Cell Cycle, 2, 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft D.R., Olson M.F. (2006) The rho gtpase effector rock regulates cyclin a, cyclin d1, and p27kip1 levels by distinct mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol., 26, 4612–4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Gatta G. et al. (2012) Reverse engineering of tlx oncogenic transcriptional networks identifies runx1 as tumor suppressor in t-all. Nat. Med., 18, 436–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GO. (2013) Gene ontology annotations and resources. Nucleic Acids Res., 41, D530–D535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann A. et al. (2010) Chea: transcription factor regulation inferred from integrating genome-wide chip-x experiments. Bioinformatics, 26, 2438–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre C. et al. (2010) A human bcell interactome identifies myb and foxm1 as master regulators of proliferation in germinal centers. Mol. Syst. Biol., 6, 337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K.C., Wang X. (2008) Gene regulatory network reconstruction using conditional mutual information. EURASIP J. Bioinf. Syst. Biol., 2008, 253894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licausi F. et al. (2011) Hre-type genes are regulated in internal oxygen concentrations during the normal development of potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers. Plant Cell Physiol., 52, 1957–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin A.A. et al. (2006) Aracne: an algorithm for the reconstruction of gene regulatory networks in a mammalian cellular context. BMC Bioinformatics, 7, S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutwil M. et al. (2011) Planet: combined sequence and expression comparisons across plant networks derived from seven species. Plant Cell, 23, 895–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr C.J. (1994) G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell, 79, 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuer R. et al. (2002) The mutual information: detecting and evaluating dependencies between variables. Bioinformatics, 18, S231–S240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TCGA. (2012) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 490, 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe G. et al. (1998) Inhibition of cyclin d1 kinase activity is associated with e2fmediated inhibition of cyclin d1 promoter activity through e2f and sp1. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 3212–3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo JH. et al. (2015) Elucidating Compound Mechanism of Action by Network Perturbation Analysis. Cell., 162, 441–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.