Abstract

Background

Sleep‐disordered breathing (SDB) has been recognized as an important risk factor for cardiovascular diseases; however, the impact of SDB on long‐term outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome has not been fully evaluated.

Methods and Results

We performed overnight cardiorespiratory monitoring of 241 patients with acute coronary syndrome who were successfully treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention between January 2005 and December 2008. The presence of SDB was defined as apnea–hypopnea index ≥5 events per hour. The end point was incidence of major adverse cardiocerebrovascular events, defined as a composite of all‐cause death, recurrence of acute coronary syndrome, nonfatal stroke, and hospital admission for congestive heart failure. Patients were followed for a median period of 5.6 years. Among the 241 patients who were finally enrolled, comorbidity of SDB with acute coronary syndrome was found in 126 patients (52.3%). The cumulative incidence of major adverse cardiocerebrovascular events was significantly higher in patients with SDB than in those without SDB (21.4% versus 7.8%, P=0.006). Multivariable analysis revealed that the presence of SDB was a significant predictor of major adverse cardiocerebrovascular events (hazard ratio 2.28, 95% CI 1.06–4.92; P=0.035).

Conclusions

The study's results showed that the presence of SDB among patients with acute coronary syndrome following primary percutaneous coronary intervention is associated with a higher incidence of major adverse cardiocerebrovascular events during long‐term follow‐up.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, percutaneous coronary intervention, prognosis, sleep‐disordered breathing

Subject Categories: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Quality and Outcomes, Risk Factors

Introduction

Sleep‐disordered breathing (SDB) has been recognized as an important risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.1 SDB may develop or worsen cardiovascular disease through intermittent hypoxia, increased oxidative stress, sympathetic overactivation, endothelial dysfunction, and activated inflammatory response.1 Nevertheless, based on the results of an epidemiological study,2 the specific relationship between SDB and development of coronary artery disease (CAD) remains controversial.

Conversely, several studies have shown a more obvious relationship between SDB and clinical outcomes in patients with CAD.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Among patients with CAD, those with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) generally have higher mortality than patients with stable angina; moreover, prognosis following ACS remains poor despite therapeutic advances including percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).8, 9 Consequently, it is important to identify factors that might contribute to worsening of clinical outcomes in patients with ACS. Although a few studies have suggested that SDB is such a factor,5, 7 the relationship between SDB and long‐term clinical outcomes following ACS has not been fully evaluated. Through this study, we aimed to test our hypothesis that SDB is associated with poor long‐term clinical outcome following ACS.

Methods

Participants

In total, 257 consecutive ACS patients who underwent primary PCI at Kokura Memorial Hospital between January 2005 and December 2008 were included in the present study. ACS includes acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non‐STEMI, and unstable angina.10, 11 The exclusion criteria were cardiac surgery during the previous 4 weeks, end‐stage renal disease requiring dialysis, cerebrovascular disease with neurological deficits, life‐threatening malignancy, obstructive lung disease, and treated SDB. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Kokura Memorial Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Initial PCI Procedure

All initial PCI procedures were performed using standard techniques. Pre‐ and postdilatation and selection of stent type were left to the operator's discretion. A bare metal stent was implanted in all patients. All patients were asked to continue aspirin (81–162 mg daily) unless there were contraindications. Ticlopidine (200 mg daily) or clopidogrel (75 mg daily) was prescribed for at least 1 month after implantation of the bare metal stent.

Sleep Study

All patients underwent an overnight sleep study ≈1 week after the onset of ACS during hospitalization, using a portable cardiorespiratory monitoring device (Pulsleep LS100; Fukuda Denshi Co, Ltd) that was equipped with a pressure sensor for monitoring airflow and snoring and a finger pulse oximeter for determining arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation (SaO2).12 In this study, apnea was defined as cessation of airflow for ≥10 seconds, and hypopnea was defined as a 50% reduction in airflow associated with ≥4% desaturation. All recordings were scored manually by experienced technicians, and the duration of sleep was estimated using the self‐reported sleep duration and recorded data, as reported previously.13, 14, 15 In the present study, the presence of SDB was defined as frequency of apneas and hypopneas (ie, apnea–hypopnea index [AHI]) ≥5 events per hour.

Definition of Risk Factors and Other Variables

Hypertension was defined as the current use of antihypertensive medications and/or systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg, measured on 3 different occasions. Diabetes mellitus was defined as the current use of insulin and/or oral antidiabetic medications or a fasting blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dL. Dyslipidemia was defined as the current use of cholesterol‐lowering medications and/or serum low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level >140 mg/dL and/or serum high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level <40 mg/dL and/or serum triglyceride level ≥150 mg/dL. With respect to a smoking habit, participants were classified as current smokers. The estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.16 Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed by echocardiography.

Outcome Data

The follow‐up period was considered to be the period from the day that the sleep study was performed to May 31, 2014. Follow‐up data were obtained by reviewing the medical records of our hospital or by contacting the patients, family members, or family physicians by telephone calls. In the present study, the end point was incidence of major adverse cardiocerebrovascular events (MACCE), defined as a composite of all‐cause death, recurrence of ACS, nonfatal stroke, and hospital admission for congestive heart failure (CHF). According to established guidelines,10, 11 recurrence of ACS was defined as recurrence of STEMI, non‐STEMI, or unstable angina. Stroke included ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke, cases of which were verified by neurologists. Hospital admission for CHF was defined as the first unscheduled admission to the cardiology ward owing to progressive symptomatic and/or hemodynamic deterioration requiring intravenous drug treatment.17, 18

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as values and percentages and mean±SD or median and interquartile range. The SDB and no‐SDB groups were compared using the unpaired Student t test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and using the chi‐square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Cumulative event‐free survival was estimated according to the Kaplan–Meier method. The log‐rank test was used to compare cumulative event‐free survival curves of SDB and no‐SDB groups. P values for log‐rank trend tests were also estimated in the analysis using AHI quartiles. In addition, Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to assess the relationship between SDB and MACCE in the entire study group and in matched patients based on propensity score (PS). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with JMP 10 software (SAS Institute) and SPSS software (IBM Corp).

Survival analyses in the entire study group

For the entire study group, univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed. On univariate analysis, the presence of SDB was used as an independent variable along with the following variables: age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, current smokers, estimated glomerular filtration rate, type of ACS, culprit vessel, LVEF, medications (antiplatelet agents, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, β‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, statins, oral hypoglycemic agents, and insulin injection), sleep duration, and mean and minimum SaO2. Variables that showed P<0.10 on univariate analysis were entered into a multivariable forward stepwise (P<0.05 for entering and excluding) Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Because distributions of estimated glomerular filtration rate and sleep duration were skewed, those variables were entered into a proportional hazards model with natural log transformation. To determine whether the results differed with the cutoff points, we performed the following additional analyses. First, hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for each quartile of AHI values were computed using the lowest quintile as the reference group in another multivariable Cox proportional hazards model including variables that showed P<0.10 on univariate analysis. Second, in a separate multivariable model, the test for determining trends in the HR by the AHI quartiles was conducted by assigning an ordinal value to each quartile. Finally, in another separate multivariable model, AHI was treated as a natural logarithm‐transformed continuous variable. The assumption of proportional hazards was assessed using a log‐minus‐log survival graph.

Survival analyses in matched patients based on PS

Because there were substantial differences in baseline characteristics between the SDB and no‐SDB groups, a PS was used to account for this predisposition bias. Propensity analysis aims to identify patients with similar probabilities of having SDB on the basis of observed clinical characteristics. We used nonparsimonious multivariable logistic regression models to estimate PS and included all baseline characteristics and sleep duration as covariates in the model. On the basis of such logistic regression results, a PS was estimated for each patient. To evaluate the discriminatory power of the logistic regression model for the PS, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (c‐statistic) was calculated. To assess PS effectiveness, the prevalence of SDB and incident MACCE according to the quartile of the PS was also assessed.

To match patients in the SDB group and those in the no‐SDB group, we computed the logit of the estimated PS for each patient. Next, we used a greedy matching algorithm to match patients using calipers that were defined to have a maximum width of 0.2 SD of the logit of the estimated PS. To determine whether PS matching produced balanced distributions of baseline characteristics across the SDB and no‐SDB groups, we compared the balance of baseline covariates between the 2 groups before and after matching by using absolute standardized differences that described the observational selection bias in the means or proportions of covariates across 2 groups and expressed these values as percentages of the pooled SD. Absolute standardized differences of <10% suggest substantial balance across groups. Cox proportional hazards regression stratified on the matched pairs was used to estimate the association of SDB with MACCE in matched patients, accounting for the matched‐pair nature of the sample.

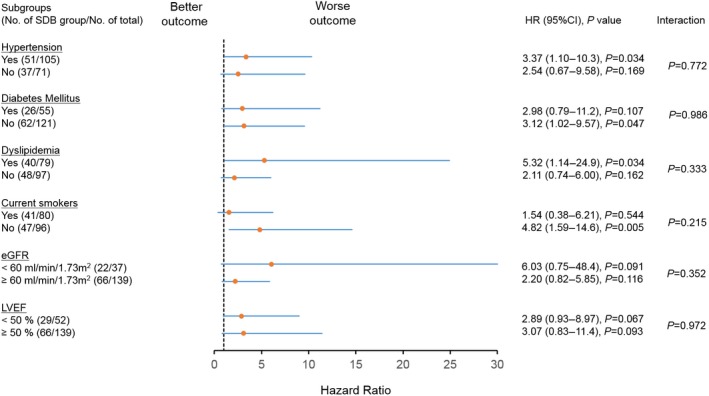

Subgroup analysis

To assess the effect modification by each risk factor on relationships between SDB and MACCE, we conducted subgroup analyses using matched patients. Subgroup characteristics included presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, current smoking, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and LVEF <50%. We formally tested for first‐order interactions using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models by entering interaction terms between SDB and the above‐mentioned subgroup variables. We also showed the effect of SDB on MACCE in each subgroup.

Results

Characteristics of Patients in the Entire Study Group

Among 257 ACS patients who underwent a sleep study, 13 patients with insufficient sleep study data and 3 patients in whom continuous positive airway pressure therapy was initiated were excluded. Finally, 241 patients were included. Among them, 209 patients had acute myocardial infarction and 32 patients had unstable angina. Procedural success of PCI was achieved in all patients. There were no major PCI‐related complications, and no recurrence of angina was observed during the index hospital stay. There were 126 patients who had SDB, and 115 patients who had no SDB. The baseline characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the SDB and no‐SDB groups except for greater body mass index, worse Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow before PCI, and lower LVEF in the SDB group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Entire Study Group

| No Sleep‐Disordered Breathing (n=115) | Sleep‐Disordered Breathing (n=126) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63±12 | 64±12 | 0.755 |

| Male, n (%) | 83 (72) | 102 (81) | 0.145 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.3±3.6 | 25.9±4.1 | 0.006 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 66 (57) | 81 (64) | 0.335 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 57 (50) | 56 (44) | 0.505 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 35 (30) | 49 (39) | 0.215 |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 53 (46) | 56 (44) | 0.899 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 6 (5) | 15 (12) | 0.108 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 72.8 (31.7) | 74.8 (26.6) | 0.444 |

| Type of acute coronary syndrome, n (%) | 0.486 | ||

| Unstable angina pectoris | 18 (16) | 14 (11) | |

| Non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction | 14 (12) | 13 (10) | |

| ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction | 83 (72) | 99 (79) | |

| Culprit lesion, n (%) | 0.667 | ||

| Right coronary artery | 48 (42) | 54 (43) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 16 (14) | 22 (18) | |

| Left anterior descending artery | 51 (44) | 50 (40) | |

| Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow before percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 0.017 | ||

| 0 | 67 (58) | 96 (76) | |

| 1 | 13 (11) | 6 (5) | |

| 2 | 16 (14) | 8 (6) | |

| 3 | 19 (17) | 16 (13) | |

| Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow after percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 0.156 | ||

| 2 | 4 (3) | 11 (9) | |

| 3 | 111 (97) | 115 (91) | |

| Peak creatine kinase, mg/dL | 1246 (1988) | 1774 (2497) | 0.130 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 58±10 | 53±12 | 0.002 |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 98 (85) | 115 (91) | 0.206 |

| Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers | 95 (84) | 108 (86) | 0.763 |

| β‐Blockers | 57 (50) | 64 (51) | 0.951 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 35 (30) | 26 (21) | 0.110 |

| Statins | 65 (57) | 77 (61) | 0.554 |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 13 (11) | 25 (20) | 0.101 |

| Insulin injection | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.999 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables or number of patients (percentage) for categorical variables.

PS and Matching Based on PS

The discriminatory power of the logistic regression model used to derive the PS was confirmed on the basis of the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (0.71). The 3 thresholds used to determine the quartiles of the PS were 0.574, 0.708, and 0.793. Prevalence of SDB within the 4 PS quartiles was 12.7%, 23.0%, 27.8%, and 36.5%, respectively. MACCE rate according to the quartiles of the PS were 15.0%, 13.3%, 13.1%, and 18.3%, respectively. These data suggest that if the prevalence of SDB is high, the probability of incident MACCE is high.

PS matching resulted in the creation of 88 matched pairs of patients in the SDB and no‐SDB groups. For 38 patients in the SDB group, no suitable control was identified. This resulted in elimination of 38 patients in the SDB group and 27 patients in the no‐SDB group from the matched analysis. Before matching, the mean PS for patients with SDB was 0.734 (95% CI 0.711–0.757) and that for patients without SDB was 0.625 (95% CI 0.595–0.654; P<0.001). After matching, the mean PS for patients with SDB was 0.683 (95% CI 0.656–0.709) and that for those without SDB was 0.677 (95% CI 0.648–0.685; P=0.943 for 2‐sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, which did not identify evidence that the 2 distributions of PS were different from each other). Baseline characteristics of matched patients are shown in Table 2. PS matching reduced the standardized difference for all variables to an absolute value <10% (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Matched Patients

| No Sleep‐Disordered Breathing (n=88) | Sleep‐Disordered Breathing (n=88) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63±12 | 63±13 |

| Male, n (%) | 66 (75) | 69 (78) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.4±3.5 | 24.7±3.8 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 54 (61) | 51 (58) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 39 (44) | 40 (46) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 29 (33) | 26 (30) |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 39 (44) | 41 (47) |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 5 (6) | 7 (8) |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 77.1 (28.6) | 74.3 (30.6) |

| Type of acute coronary syndrome, n (%) | ||

| Unstable angina pectoris | 13 (15) | 13 (15) |

| Non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction | 10 (11) | 9 (10) |

| ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction | 65 (74) | 66 (75) |

| Culprit lesion, n (%) | ||

| Right coronary artery | 37 (42) | 38 (43) |

| Left circumflex artery | 11 (13) | 14 (16) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 40 (45) | 36 (41) |

| Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow before percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 57 (65) | 59 (67) |

| 1 | 8 (9) | 6 (7) |

| 2 | 10 (11) | 8 (9) |

| 3 | 13 (15) | 15 (17) |

| Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow after percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | ||

| 2 | 4 (5) | 6 (7) |

| 3 | 84 (95) | 82 (93) |

| Peak creatine kinase, mg/dL | 1475 (1953) | 1790 (2706) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 57±10 | 56±12 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 81 (92) | 79 (90) |

| Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers | 76 (86) | 74 (84) |

| β‐Blockers | 45 (51) | 45 (51) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 21 (24) | 22 (25) |

| Statins | 49 (56) | 51 (58) |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 12 (14) | 10 (11) |

| Insulin injection | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

Data are presented as mean±SD or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables or number of patients (percentage) for categorical variables.

Figure 1.

Absolute standardized differences before and after PS matching. PS matching reduced the standardized difference for all variables to an absolute value <10%. ACE‐I indicates angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CCB, calcium channel blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PS, propensity score; RCA, right coronary artery; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

Sleep Study Data

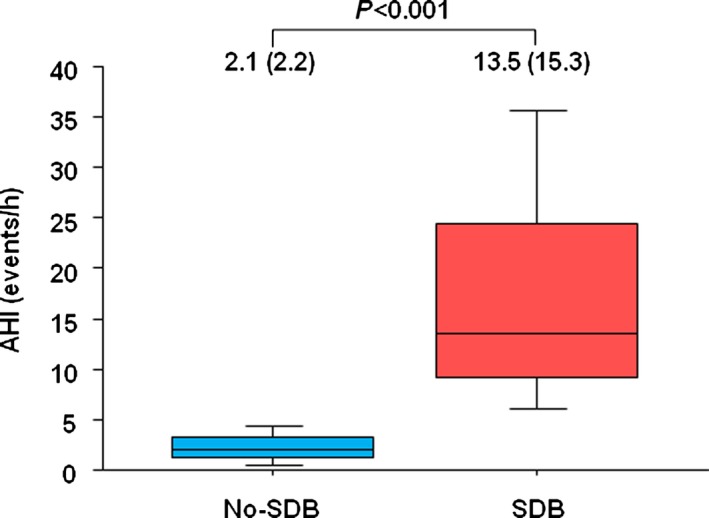

In the entire study group, participants underwent an overnight sleep study at a median of 6 days (interquartile range 2) from ACS onset. The AHI ranged from 0.1 to 51.3. Although sleep duration (Median=507.0 [IRQ=65.0] minutes in the SDB group and Median=516.0 [IRQ=61.5] minutes in the no‐SDB group, P=0.232) and mean SaO2 (94.3±8.2% in the SDB group and 95.8±1.2% in the no‐SDB group, P=0.056) were similar, patients with SDB had lower minimum SaO2 (81.8±8.3% versus 84.7±8.2%, P=0.018) and higher AHI values (13.5 [15.3] versus 2.1 [2.2] events per hour, P<0.001) (Figure 2) than those without SDB.

Figure 2.

AHI in SDB and no‐SDB groups. The AHI was significantly greater in patients with SDB than in those without SDB (13.5 [15.3] events per hour in the SDB group vs 2.1 [2.2] events per hour in the non‐SDB group, P< ;0.001). AHI indicates apnea hypopnea index; SDB, sleep‐disordered breathing.

In matched patients, sleep duration and mean SaO2 were similar between the 2 groups (508 [65.0] minutes and 95.9±1.3% in the SDB group and 516 [60] minutes and 95.1±2.3% in the no‐SDB group, P=0.747 and P=0.109, respectively), whereas the minimum SaO2 was significantly lower in the SDB group than in the no‐SDB group (82.5±7.6% in the SDB group and 85.6±8.5% in the no‐SDB group, P<0.001). Patients with SDB had higher AHI values (12.4 [14.1] versus 2.0 [2.4] events per hour, P<0.001) than those without SDB.

Outcomes

During the median follow‐up of 5.6 years (interquartile range 2.8 years), 27 patients (21.4%) in the SDB group and 9 patients (7.8%) in the no‐SDB group had MACCE. Details of MACCE in the entire study group are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Details of Major Adverse Cardiocerebrovascular Events in the Entire Study Group

| No Sleep‐Disordered Breathing (n=115) | Sleep‐Disordered Breathing (n=126) | |

|---|---|---|

| Major adverse cardiocerebrovascular events | 9 (7.8) | 27 (21.4) |

| Death | 3 (2.6) | 10 (7.8) |

| Recurrence of acute coronary syndrome | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.6) |

| Nonfatal stroke | 3 (2.6) | 4 (3.2) |

| Admission for congestive heart failure | 1 (0.9) | 11 (8.7) |

Data are presented as number of patients (percentage).

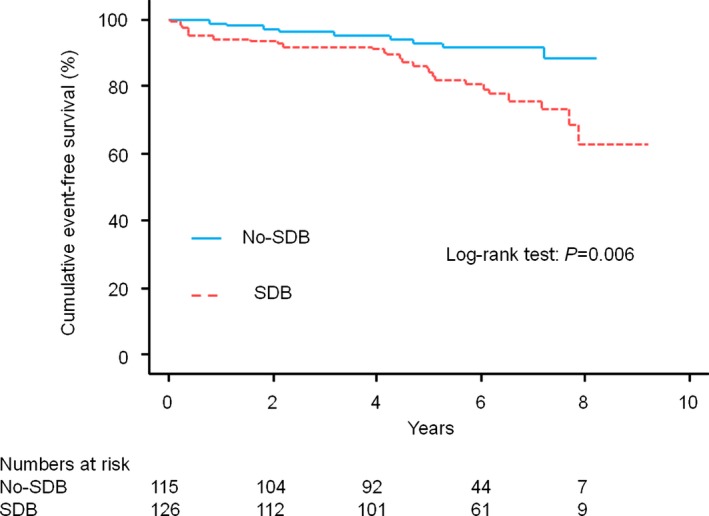

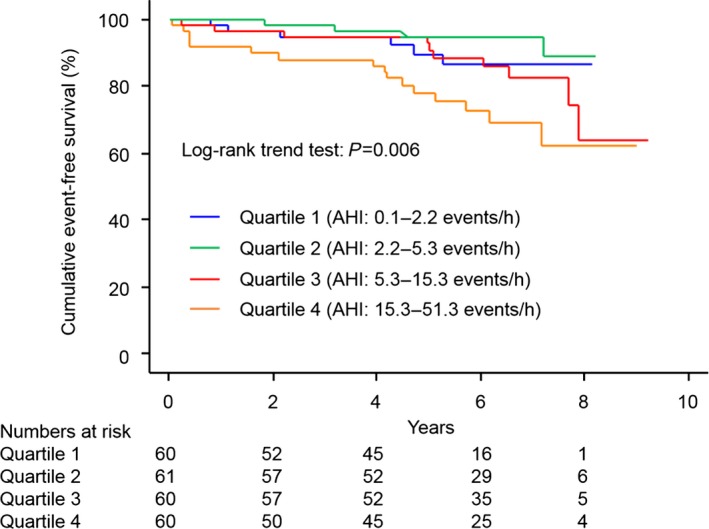

In the entire study group, cumulative event‐free survival was significantly lower in patients with SDB than in those without SDB (Figure 3). On univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, age (per 1‐year increment; HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.07; P=0.014), current smokers (HR 1.96, 95% CI 0.96–3.99; P=0.063), LVEF (per 1% increment; HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.93–0.98; P<0.001), mean SaO2 (per 1% increment; HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.96–1.00; P=0.057), minimum SaO2 (per 1% increment; HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.94–0.99; P=0.022), use of β‐blockers (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.91–3.49; P=0.094), use of statins (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.24–0.93; P=0.030), and the presence of SDB (HR 2.74, 95% CI 1.29–5.82; P=0.009) showed values with P<0.1 and were included in the multivariable analysis. The final multivariable stepwise regression model is shown in Table 4. In the multivariable analysis, presence of SDB was a significant predictor for MACCE along with increase in age, decrease in LVEF and mean SaO2, absence of β‐blocker treatment, and absence of statin treatment. The results of additional analyses in which AHI quartiles were compared with the test of trends in the HR by AHI quartiles and in which AHI was treated as a natural logarithm‐transformed continuous variable indicated that the greater the AHI, the greater the risk of MACCE (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

Cumulative event‐free survival curves in the entire study group. Patients with SDB had a significantly lower cumulative event‐free survival (red dotted line) than that in those without SDB (blue solid line) (log‐rank test, P=0.006). SDB indicates sleep‐disordered breathing.

Table 4.

Final Multivariable Stepwise Regression Models for Major Adverse Cardiocerebrovascular Events in the Entire Study Group

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 0.007 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) | 0.001 |

| β‐Blockers | 0.47 (0.24–0.94) | 0.033 |

| Statins | 0.37 (0.19–0.75) | 0.006 |

| Mean arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.015 |

| Sleep‐disordered breathing | 2.28 (1.06–4.92) | 0.035 |

Figure 4.

Cumulative event‐free survival curves according to the AHI quartiles in the entire study group. There was a significant trend of worse cumulative event‐free survival as quartile increased. AHI indicates apnea–hypopnea index.

Figure 5.

Multivariable HR for MACCE according to the quartile of the AHI and logarithm‐transformed AHI for the entire study group. HR increased significantly with the AHI quartiles and logarithm‐transformed AHI in a dose‐dependent manner for MACCE. There was a significant trend toward worse cumulative event‐free survival as the quartile increased. AHI indicates apnea–hypopnea index; HR, hazard ratio; MACCE, major adverse cardio‐cerebrovascular events.

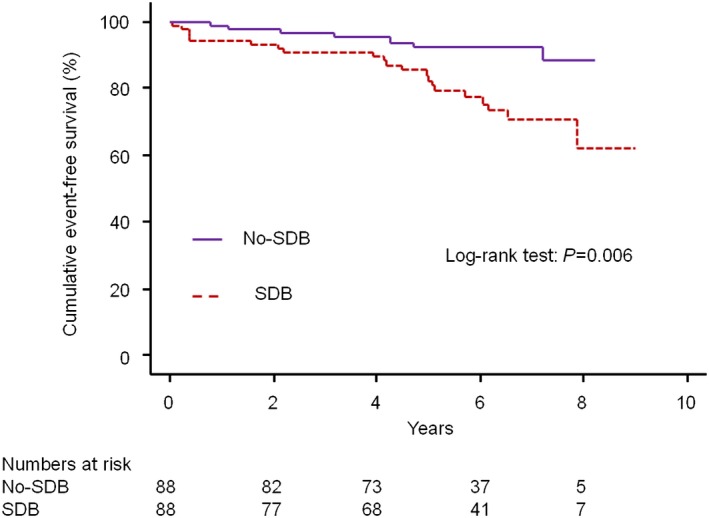

Among matched patients, the presence of SDB was significantly associated with an increase in MACCE (Figure 6). Risk of MACCE was also significantly greater in the SDB group than in the no‐SDB group (HR 4.25, 95% CI 1.43–12.6; P=0.009). There were no significant interactions between SDB and any subgroups (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Cumulative event‐free survival curves in matched patients. Patients with SDB had significantly lower cumulative event‐free survival (brown dotted line) than that of those without SDB (purple solid line) (log‐rank test, P=0.006). SDB indicates sleep‐disordered breathing.

Figure 7.

Association between SDB and MACCE in subgroups of matched patients. There were no significant interactions between SDB and any subgroups. eGFR indicates estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SDB, sleep‐disordered breathing.

Discussion

Our study resulted in 2 important observations. First, we found that the presence of SDB was associated with poor long‐term outcomes in ACS patients following primary PCI, consistent with previous reports in which only patients with stable CAD were enrolled3, 4, 6 or short‐term outcomes were investigated in ACS patients following PCI.5, 7 This association was confirmed by several separate analytical techniques: conventional multivariable analysis using the presence or absence of SDB, multivariable analysis using AHI quartiles or logarithm‐transformed AHI instead of presence or absence of SDB, and comparisons using matched patients based on PS. Consistent results in all analyses would further support the plausibility of the finding. Furthermore, results of tests for subgroup–SDB effect interaction suggested that the SDB effect on MACCE was not different across subgroups. Second, we found that the AHI determined by this particular cardiorespiratory monitoring device can be a predictor for long‐term clinical outcomes. These findings provide insights into the clinical significance of SDB and perhaps its role in the treatment of ACS patients following primary PCI.

In previous studies, SDB has been shown to be associated with poor prognosis in patients with stable CAD.3, 4, 6 As shown previously by Peker and colleagues, untreated SDB is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with CAD.3 Mooe and colleagues reported that SDB is associated with worse prognosis in patients with CAD, and there is an independent association with cerebrovascular events.4 Valham and colleagues also reported that SDB is significantly associated with the risk of stroke among patients with CAD.6 In all of these reports, however, patients had stable CAD, and PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting were not performed for all patients, possibly affecting the results. In contrast, Yumino and colleagues reported the adverse effect of SDB (defined as AHI ≥10 events per hour) on clinical outcomes following PCI in patients with ACS.5 In their report, clinical outcomes included target vessel revascularization (TVR), and in fact, TVR was the most common adverse clinical outcome; however, the relatively short follow‐up period (≈8 months) might have resulted in lower incidence of adverse events other than TVR. In the present study, we did not include TVR in MACCE because in‐stent restenosis may be caused partly by technical issues and performed mainly on the occasion of planned follow‐up angiography in the bare metal stent era. Lee and colleagues recently reported that 42% of the patients admitted with STEMI had severe SDB (ie, AHI ≥30 events per hour) that was associated with a worse event‐free survival rate at 18‐month follow‐up.7 Their study also included TVR in adverse events, and only patients with STEMI were enrolled. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to show a negative impact of SDB on long‐term (>5 years) clinical outcomes other than TVR in ACS patients following PCI.

In terms of specific causes of MACCE, hospital admission for CHF was the most common cause of MACCE in the present study. Patients with reduced LVEF in association with myocardial infarction might have contributed to the increased risk of CHF development in patients with SDB. Nakashima and colleagues reported that SDB showed negative effects on the recovery of left ventricular systolic function in patients with acute myocardial infarction.19 The infarct size is an important prognostic factor of left ventricular remodeling following heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Recently, primary PCI for patients with ACS has become common and contributes substantially to reducing infarct size; however, the management of patients with ACS after PCI has not been fully examined for the purpose of reducing infarct size. Buchner and colleagues reported that SDB caused a larger infarct area and impaired healing after PCI in patients with acute myocardial infarction.20 This could be a potential mechanism in the association between the presence of SDB and poor long‐term clinical outcomes, especially an increased risk of hospital admission for CHF. In the study by Cassar and colleagues,21 following PCI, CAD patients with properly treated SDB showed lower incidence of cardiac death than those who had not received SDB treatment; this suggested a cause‐and‐effect relationship between SDB and poor clinical outcomes in patients with CAD. Consequently, randomized controlled studies regarding the effects of SDB treatment on clinical outcomes are warranted.

It appears that detecting SDB should be included into the routine clinical care of hospitalized patients following ACS events and primary PCI. In previous studies, the impact of SDB on short‐term clinical outcomes was investigated based on the results from various portable cardiorespiratory monitoring devices with different cutoff levels of AHI.5, 7 In the present study, another portable cardiorespiratory monitoring device was used to determine presence of SDB. Based on this device, AHI ≥5 events per hour could predict long‐term clinical outcomes, which included patients with even milder SDB than previous studies.5, 7 These results may suggest that more severe SDB can affect early clinical events mainly related to vasculatures (ie, TVR) and that late clinical events related to myocardium or hemodynamics (ie, CHF) can be predicted by even milder SDB. Conversely, such differences in the cutoff level of AHI might be explained simply by the difference in the types of devices. Nevertheless, because of the limited awareness of SDB among cardiologists caring for hospitalized patients following ACS and limited access to and the relatively high cost of in‐laboratory polysomnography, only a minority of ACS patients benefit from the identification of SDB. It should be noted that portable cardiorespiratory monitoring, which provides a readily available and inexpensive means of detecting SDB, has a prognostic impact on long‐term clinical outcomes.

This study has certain limitations. First, SDB was detected using cardiorespiratory monitoring rather than fully equipped polysomnography; however, as noted, it may not be feasible for all hospitalized patients to undergo fully equipped polysomnography following ACS and primary PCI. In the present study, we specifically evaluated whether we could identify patients at high risk for the incidence of MACCE by using a simple modality for determining the long‐term clinical outcome, as we need a simple, inexpensive, feasible, and sensitive and specific tool for identifying SDB, even in this patient population, and for identification of risk factors by cardiologists themselves and not by other specialists (eg, sleep or respiratory specialists). Duration of sleep was estimated using self‐reported sleep duration, and this might lead to underestimation of the AHI as a consequence of overestimating actual sleeping time. Second, the present study is a single‐center observational study, and both the sample size and the number of outcome events are relatively small. The present study, however, would be the first study investigating the impact of SDB on long‐term outcomes and includes the largest sample of ACS patients with primary PCI. Third, even though we performed multivariable analyses and analysis using matched patients based on PS, other unknown confounders might have affected the analysis. Furthermore, in the present study, drug‐eluting stents were not used, and bare metal stents were implanted for all patients. Consequently, it is difficult to determine whether the use of drug‐eluting stents could have improved the results in the recent era of PCI. Further investigation is needed to clarify whether the presence of SDB will affect the long‐term clinical outcomes in the drug‐eluting stent era.

In conclusion, the present study showed that the presence of SDB among ACS patients following primary PCI is associated with a higher incidence of MACCE, especially the incidence of CHF events, during long‐term follow‐up periods. Randomized clinical trials investigating whether specific treatment for coexisting SDB in ACS patients following PCI would cause an improvement in clinical outcomes will provide further information regarding the importance of detecting SDB in patients following ACS and PCI.

Disclosures

Kasai is affiliated with a department endowed by Philips Respironics, ResMed, Teijin Home Healthcare, and Fukuda Denshi. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Makoto Morita and Junichi Michikoshi for assistance with this work.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003270 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003270)

References

- 1. Kasai T, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: a bidirectional relationship. Circulation. 2012;126:1495–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gottlieb DJ, Yenokyan G, Newman AB, O'Connor GT, Punjabi NM, Quan SF, Redline S, Resnick HE, Tong EK, Diener‐West M, Shahar E. Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Circulation. 2010;122:352–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peker Y, Hedner J, Kraiczi H, Löth S. Respiratory disturbance index: an independent predictor of mortality in coronary artery disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mooe T, Franklin KA, Holmström K, Rabben T, Wiklund U. Sleep‐disordered breathing and coronary artery disease: long‐term prognosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1910–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yumino D, Tsurumi Y, Takagi A, Suzuki K, Kasanuki H. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on clinical and angiographic outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Valham F, Mooe T, Rabben T, Stenlund H, Wiklund U, Franklin KA. Increased risk of stroke in patients with coronary artery disease and sleep apnea: a 10‐year follow‐up. Circulation. 2008;118:955–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee CH, Khoo SM, Chan MY, Wong HB, Low AF, Phua QH, Richards AM, Tan HC, Yeo TC. Severe obstructive sleep apnea and outcomes following myocardial infarction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:616–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alcock RF, Yong AS, Ng AC, Chow V, Cheruvu C, Aliprandi‐Costa B, Lowe HC, Kritharides L, Brieger DB. Acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary artery disease: are they so different? Long‐term outcomes in a contemporary PCI cohort. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1343–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giustino G, Baber U, Stefanini GG, Aquino M, Stone GW, Sartori S, Steg PG, Wijns W, Smits PC, Jeger RV, Leon MB, Windecker S, Serruys PW, Morice MC, Camenzind E, Weisz G, Kandzari D, Dangas GD, Mastoris I, Von Birgelen C, Galatius S, Kimura T, Mikhail G, Itchhaporia D, Mehta L, Ortega R, Kim HS, Valgimigli M, Kastrati A, Chieffo A, Mehran R. Impact of clinical presentation (stable angina pectoris vs unstable angina pectoris or non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction vs ST‐elevation myocardial infarction) on long‐term outcomes in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with drug‐eluting stents. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC Jr, King SB III, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE Jr, Green LA, Hochman JS, Jacobs AK, Krumholz HM, Morrison DA, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Peterson ED, Sloan MA, Whitlow PL, Williams DO. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients With ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2009;120:2271–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE Jr, Chavey WE II, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS, Smith SC Jr; 2011 WRITING GROUP MEMBERS; ACCF/AHA TASK FORCE MEMBERS . 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123:e426–e579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iida‐Kondo C, Yoshino N, Kurabayashi T, Mataki S, Hasegawa M, Kurosaki N. Comparison of tongue volume/oral cavity volume ratio between obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients and normal adults using magnetic resonance imaging. J Med Dent Sci. 2006;53:119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, Claman D, Goldberg R, Gottlieb DJ, Hudgel D, Sateia M, Schwab R; Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:737–747. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meoli AL, Casey KR, Clark RW, Coleman JA Jr, Fayle RW, Troell RJ, Iber C; Clinical Practice Review Committee . Hypopnea in sleep‐disordered breathing in adults. Sleep. 2001;24:469–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, Gozal D, Iber C, Kapur VK, Marcus CL, Mehra R, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Redline S, Strohl KP, Davidson Ward SL, Tangredi MM; American Academy of Sleep Medicine . Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:597–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, Yamagata K, Tomino Y, Yokoyama H, Hishida A; Collaborators developing the Japanese equation for estimated GFR . Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez‐Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Køber L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Rønnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines . ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Harty B, Heitner JF, Kenwood CT, Lewis EF, O'Meara E, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, Yang S, McKinlay SM; TOPCAT Investigators . Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1383–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakashima H, Katayama T, Takagi C, Amenomori K, Ishizaki M, Honda Y, Suzuki S. Obstructive sleep apnoea inhibits the recovery of left ventricular function in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2317–2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buchner S, Satzl A, Debl K, Hetzenecker A, Luchner A, Husser O, Hamer OW, Poschenrieder F, Fellner C, Zeman F, Riegger GA, Pfeifer M, Arzt M. Impact of sleep‐disordered breathing on myocardial salvage and infarct size in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cassar A, Morgenthaler TI, Lennon RJ, Rihal CS, Lerman A. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea is associated with decreased cardiac death after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1310–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]