Abstract

The circadian-related hormones, melatonin and cortisol, have oncostatic and immunosuppressive properties. This study examined the relationship between these two biomarkers and the presence of prostate cancer. We measured their major metabolites in urine collected from 120 newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients and 240 age-matched controls from January 2011 to April 2014. Compared with patients with lower urinary melatonin-sulfate or melatonin-sulfate/cortisol (MT/C) ratio levels, those with above-median levels were significantly less likely to have prostate cancer (adjusted OR (aOR) = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.35–0.99; aOR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.27–0.77) or advanced stage prostate cancer (aOR = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.26–0.89; aOR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.17–0.62). The combined effect of both low MT/C ratios and PSA levels exceeding 10 ng/ml was an 8.82-fold greater likelihood of prostate cancer and a 32.06-fold greater likelihood of advanced stage prostate cancer, compared to those with both high MT/C ratios and PSA levels less than 10 ng/ml. In conclusion, patients with high melatonin-sulfate levels or a high MT/C ratio were less likely to have prostate cancer or advanced stage prostate. Besides, a finding of a low MT/C ratio combined with a PSA level exceeding 10 ng/ml showed the greatest potential in detecting prostate cancer and advanced stage prostate cancer.

Twenty-four hour biological rhythms allow organisms to tune their physiology to the daily cycle of sunlight and darkness. It has been suggested that the disruption of biological rhythms, or the mismatch between the sleep/wake cycle and the endogenous circadian timing system, may contribute to short- and long-term adverse effects as well as cancer risk1. Melatonin, a circadian and circannual time signal secreted by the human pineal gland2,3, is known to have significant anticancer potential and has been found to have chemopreventive, oncostatic, and tumor inhibitory effects in a variety of in vitro and in vivo experimental models of neoplasia4,5,6. It is also an anti-physical stress hormone7,8, an immunomodulatory agent9,10, and a powerful and effective endogenous hydroxyl radical scavenger11,12, and, as such, it has both direct and indirect anticancer effects.

Most cancer research on melatonin in the past three decades has largely centered on breast cancer13,14,15,16,17,18,19, the most common female cancer20. However, there are few studies investigating the potential role of melatonin in human prostate cancer, the most commonly diagnosed non-cutaneous cancer in men20. Prostate and breast cancer are similar in that both are sex hormone-dependent21. Many studies have found an association between circadian disruption, including melatonin levels, and breast cancer, but few studies have investigated the association between circadian disruption or sleep loss and prostate cancer risk, which has been found to be positive22.

The fact that patients with prostate cancer have lower melatonin levels than patients with BPH suggests that melatonin may protect against disease severity23. Melatonin has been found to have potential in the chemoprevention and treatment of prostate cancer in vitro studies24. Cortisol is another hormone important to circadian regulation25,26. One previous study revealed that cortisol secretion patterns may be impacted by shift work, which is known to cause circadian disruption27. This hormone has been found to influence cancer risk through its effects on immune function28,29. It is thus possible that carcinogenicity of circadian disruption can broadly affect many sites among both men and women via melatonin and cortisol levels. Therefore, we conducted this case-control study to examine the relationship between two urine biomarkers of circadian regulation hormones, melatonin and cortisol level, and the presence of prostate cancer and their impacts on the clinical stages of prostate cancer. Because PSA is also associated with the presence or relapse of prostate cancer, this antigen was also included to examine the interaction effect of circadian regulation hormones and PSA on prostate cancer.

Results

In total, we recruited 137 pathology-proved prostate cancer patients and 274 male controls (average: 70.53 years; range 45 to 85 years) between January 2011 and April 2014. After excluding cases with other cancers or cases without available individual matches, we were left with 120 cases and 240 controls to include in our final analysis. As can be seen in Table 1, summary of participant characteristics, the only significant difference between the cases and controls were PSA levels (p < 0.001). Most (75.0%) of those included in the study were 65 years old or older, had high school or college educations or less (76.7%), were married (87.7%), had no family history of prostate cancer (85.5%), did not smoke (70.1%), use alcohol (88.8%), chew betel nut (98.3%), or use vitamin D supplements (96.6%). There were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to these characteristics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of all participants.

| N | CasesN =120 | ControlsN = 240 | χ2 test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.796 | ||

| <65 y/o | 29 (24.2) | 61 (25.4) | |

| ≥65 y/o | 91 (75.8) | 179 (74.6) | |

| Education | 0.635 | ||

| high school & college | 91 (75.9) | 185 (78.1) | |

| ≥university | 29 (24.1) | 52 (21.9) | |

| Marital status | 0.201 | ||

| married | 109 (90.8) | 205 (86.1) | |

| others | 11 (9.2) | 33 (13.9) | |

| Family history of PCa | 0.352 | ||

| No | 98 (83.1) | 203 (86.7) | |

| Yes | 20 (16.9) | 31 (13.3) | |

| Smoking | 0.974 | ||

| Never | 84 (70.0) | 167 (70.2) | |

| Former or current | 36 (30.0) | 71 (29.8) | |

| Alcohol | 0.103 | ||

| Never | 102 (85.0) | 216 (90.8) | |

| Former or current | 18 (15.0) | 22 (9.2) | |

| Betel nut | 0.079* | ||

| Never | 120 (100.0) | 231 (97.5) | |

| Former or current | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.5) | |

| Vitamin D supplement | 0.068* | ||

| No | 119 (99.2) | 227 (95.4) | |

| Yes (>1 times/month) | 1 (0.8) | 11 (4.6) | |

| Preoperative PSA level | <0.001 | ||

| <10 ng/ml | 26 (21.8) | 120 (52.4) | |

| ≥10 ng/ml | 93 (78.2) | 109 (47.6) |

Abbreviation: PCa = prostate cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

*Fisher’s exact test.

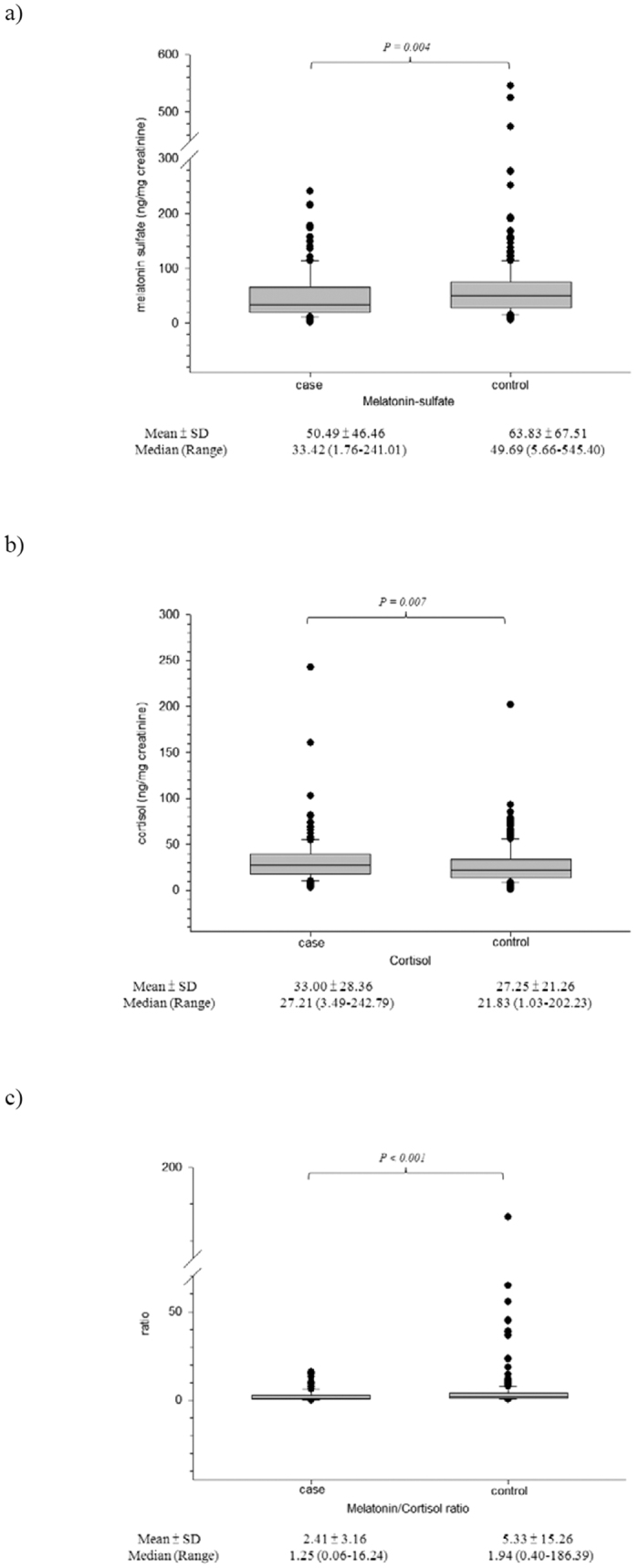

Figure 1 shows the differences in the urinary biomarkers between cases and controls. Compared to the controls, the cases had a significantly lower levels of the urinary melatonin-sulfate (mean ± SD) (50.49 ± 46.46 vs. 63.83 ± 67.51 ng/mg creatinine, p = 0.004) and lower MT/C ratios (2.41 ± 3.16 vs. 5.33 ± 15.26, p < 0.001). In contrast, the cases had significantly higher mean urinary cortisol levels than the controls (33.00 ± 28.36 vs. 27.25 ± 21.26 ng/mg creatinine, p = 0.007).

Figure 1. Urinary biomarkers of circadian hormone between case and control groups.

(a) melatonin; (b) cortisol; (c) ratio of melatonin/cortisol.

After adjusting for other covariates, we found that subjects with high urinary melatonin-sulfate or MT/C ratios were significantly less likely to have prostate cancer compared to those with low urinary melatonin-sulfate or MT/C ratios (adjusted OR (aOR) = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.35–0.99 and aOR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.27–0.77, respectively) (Table 2). In addition, subjects with both high MT/C ratio and a pre-operative PSA level exceeding 10 ng/ml were 3.61 fold more likely (95% CI = 1.62–8.07) to have prostate cancer, when compared to those with both high MT/C ratio and a pre-operative PSA level less than 10 ng/ml. (Table 2). The risk was even higher in the group with low MT/C ratios and pre-operative PSA levels exceeding 10 ng/ml (aOR = 8.82), (95% CI = 3.98–19.55). A similar risk pattern was also observed among the subjects when we combined risk of melatonin sulfate or cortisol and PSA level (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 2. Association between urinary biomarkers of circadian hormone dichotomized by medians and the presence of prostate cancer.

| Variables | ControlsN = 240 | CasesN = 120 | OR | 95% CI | aOR1 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | |||||||

| Melatonin2 | |||||||

| Low | 107 (44.6) | 73 (60.8) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| High | 133 (55.4) | 47 (39.2) | 0.52 | 0.33–0.81 | 0.59 | 0.35–0.99 | |

| Cortisol2 | |||||||

| Low | 130 (54.2) | 50 (41.7) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| High | 110 (45.8) | 70 (58.3) | 1.65 | 1.06–2.59 | 1.43 | 0.90–2.28 | |

| MT/C ratio2 | |||||||

| Low | 105 (43.8) | 75 (62.5) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| High | 135 (56.2) | 45 (37.5) | 0.47 | 0.30–0.73 | 0.46 | 0.27–0.77 | |

| MT/C ratio2 | PSA level | ||||||

| High | <10 | 64 (27.9) | 10 (8.4) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) |

| Low | <10 | 56 (24.5) | 16 (13.4) | 1.82 | 0.77–4.35 | 1.92 | 0.79–4.64 |

| High | ≥10 | 62 (27.1) | 34 (28.6) | 3.51 | 1.60–7.71 | 3.61 | 1.62–8.07 |

| Low | ≥10 | 47 (20.5) | 59 (49.6) | 8.03 | 3.72–17.33 | 8.82 | 3.98–19.55 |

Abbreviation: MT/C ratio = melatonion/cortisol ratio.

1Adjusting for age (<65 vs. ≥65 yr), personal habits of smoking, alcohol, betel nut, family history of prostate cancer, and prostate-specific antigen level (<10 vs. ≥10 ng/ml).

2Medians of 43.23 ng/mg creatinine for melatonin, 24.06 ng/mg creatinine for cortisol, and 1.76 for MT/C ratio.

Categorizing prostate cancer by clinical stage (localized and advanced), we found significant differences of urinary biomarkers when comparing advanced cancer and control groups. No multiplicative scale of interaction was obtained for the MT/C ratio and PSA level (Table 3). In addition, we found evidence of a combined effect of low MT/C ratio and the pre-operative PSA levels exceeding 10 ng/ml in the advanced cancer group compared with either control group or localized cancer group (Table 3). A similar trend pattern was also observed among the subjects when combining melatonin sulfate or cortisol and PSA level (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 3. Association between urinary biomarkers of circadian hormone dichotomized by medians and clinical staging of prostate cancer.

| Factor/category | ControlN = 240 | Localized1N = 51 | Advanced1N = 69 | Localized1

vs. control |

Advanced1

vs. control |

Advanced1

vs. localized1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | aOR2 | (95% CI) | aOR2 | (95% CI) | aOR2 | (95% CI) | ||||

| Melatonin3 | ||||||||||

| Low | 107 (44.6) | 27 (52.9) | 46 (66.7) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| High | 133 (55.4) | 24 (47.1 | 23 (33.3) | 0.72 | 0.38–1.36 | 0.49 | 0.26–0.89 | 0.59 | 0.27–1.28 | |

| Cortisol3 | ||||||||||

| Low | 130 (54.2) | 24 (47.1) | 26 (37.7) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| High | 110 (45.8) | 27 (52.9) | 43 (62.3) | 1.28 | 0.68–2.41 | 1.96 | 1.07–3.57 | 1.87 | 0.87–4.01 | |

| MT/C ratio3 | ||||||||||

| Low | 105 (43.8) | 27 (52.9) | 48 (69.6) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| High | 135 (56.2) | 24 (47.1) | 21 (30.4) | 0.63 | 0.33–1.20 | 0.33 | 0.17–0.62 | 0.44 | 0.20–0.99 | |

| Preoperative PSA | ||||||||||

| <10 ng/ml | 120 (52.4) | 18 (36.0) | 8 (11.6) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| ≥10 ng/ml | 109 (47.6) | 32 (64.0) | 61 (88.4) | 2.13 | 1.10–4.15 | 8.17 | 3.77–17.72 | 3.88 | 1.49–10.09 | |

| MT/C ratio3 | PSA level | |||||||||

| High | <10 | 64 (27.9) | 8 (16.0) | 2 (2.9) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) |

| Low | <10 | 56 (24.5) | 10 (20.0) | 6 (8.7) | 1.44 | 0.52–3.97 | 3.71 | 0.71–19.44 | 2.57 | 0.40–16.64 |

| High | ≥10 | 62 (27.1) | 15 (30.0) | 19 (27.5) | 2.16 | 0.85–5.46 | 9.36 | 2.04–42.91 | 4.34 | 0.79–23.93 |

| Low | ≥10 | 47 (20.5) | 17 (34.0) | 42 (60.9) | 3.41 | 1.34–8.69 | 32.06 | 7.17–143.29 | 9.41 | 1.77–50.07 |

| P for multiplicative interaction | 0.888 | 0.930 | 0.871 | |||||||

Abbreviation: MT/C ratio = melatonion/cortisol ratio; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

1Localized PCa defined as stage T1 or T2 at diagnosis; Advanced PCa defined as stage T3 or T4 and or LN or distant metastases at diagnosis.

2Adjusting for the same variables in Table 2.

3Medians of 43.23 ng/mg creatinine for melatonin, 24.06 ng/mg creatinine for cortisol, and 1.76 for MT/C ratio.

Discussion

In this case-control study, we found an inverse relation between first morning urinary melatonin-sulfate levels and the melatonin/cortisol (MT/C) ratio and the presence of prostate cancer overall and advanced stage prostate cancer.

Most prior studies have focused on evaluating the association between melatonin levels and breast cancer. Very few have focused on the association between melatonin and prostate cancer. One cross-sectional study by Bartsch et al. reported that men with prostate cancer had lower melatonin levels than men with BPH23. Another case-cohort study in an Icelandic population, conducted by Sigurdardottir et al., found that subjects with below-median morning pre-diagnostic 6-sulfatoxymelatonin (aMT6s) levels had a statistically significant 4-fold increased risk for advanced disease, compared to those with above-median levels (Hazard ratio = 4.04; 95% CI = 1.26–12.98)30. However, that study did not find a significant association between morning urinary aMT6s levels and prostate cancer risk overall. Our study contributes additional information about circadian hormones and the presence of prostate cancer in an Asian population.

The protective effect of melatonin on cancer risk may be related to its inhibition of cancer cell growth, its protection of cells from DNA damage, and its promotion of repair of DNA damage once it has occurred1,31,32. Recently, Blask et al. conducted a series of experiments using both steroid receptor-positive and -negative human breast cancer xenografts in rats and found an inverse relationship between melatonin level and tumor activity33,34. The same research group also reported similar results with prostate cancer xenografts35. Other studies have reported a reduction in growth of malignant prostate tumor cells achieved by the administration of both pharmacologic and physiologic doses of melatonin24,36,37,38, although their findings have not always been consistent39,40.

Our study also measured cortisol, another important circadian hormone secreted by the adrenal cortex. Cortisol has been found to help regulate both immunity and inflammation; a deficiency in this hormone may result in an unresponsive immune system and an overabundance of the hormone may suppress immune responses41. Moreover, chronic dysregulation of the circadian cortisol rhythm has been associated with higher levels of inflammation28, and such inflammation may play a critical role in carcinogenesis42. Mirick et al. found that circadian disruption can impact cortisol secretion patterns, which may in turn affect cancer risk27. Although this study did not find a significant association between one-spot morning urinary cortisol level and prostate cancer, we did find an inverse association between the MT/C ratio and the presence of prostate cancer and advanced stage prostate cancer. Previous studies have found MT/C ratio to be related to different types of depression and the severity of depression43,44. This is the first study to evaluate the association between the MT/C ratio and the presence of prostate cancer.

It is difficult to decide clinically whether to perform an invasive prostate biopsy for subjects with abnormal PSA levels. Our finding that the combination of low MT/C ratios and PAS levels in excess of 10 ng/ml conferred the highest tendency that a person may have prostate cancer and advanced-stage disease prostate cancer suggests that we might consider the biomarker of MT/C ratio in urine to be an additional tool for judging whether the prostate biopsy is needed or not, when PSA levels are elevated. Further study is needed to investigate the clinical utility of the combining PSA and MT/C to detect the presence of prostate cancer and stage the disease.

A high proportion of controls in this study had PSA levels exceeding10 ng/ml. Increased PSA concentrations are found in the sera of patients with BPH or patients with prostate cancer, respectively45. An estimated 50% of men have histologic evidence of BPH by age 50, 75% by age 80, and 90% of men by age 85 years46. About 99% of prostate cancer cases occur in those over the age of 5047. This is of particular concern in older men, where BPH is more prevalent, as BPH increases gland volume which in turn increases the PSA level as well as the number of sampling errors associated with prostate biopsy48,49. For men with PSA 4–10 ng/mL, the detection rate of PCa in Caucasian men may be as high as 40%50,51 but only 20% in Chinese men52. Although the inclusion criteria for our control group was either unremarkable digital rectal exams or remarkable digital rectal exams but histologically confirmed BPH, our control group may have included some men with undiagnosed prostate cancer. However, the inclusion of such patients as controls would only lead to underestimations of the true association.

The strengths of our study are that we were able to consider the most important prostate cancer risk factors, including clinical stage and PSA level in our analyses. Furthermore, we considered two important circadian biomarkers and found the M/C ratio is more relevant to prostate cancer. This study also has several limitations. One limitation is that it is a cross-sectional case-control study, so no clear causal relationship can be inferred. There is a likelihood of a reverse causality between circadian hormones and the presence of prostate cancer, if circadian disruption and/or sleep disruption following a cancer diagnosis results in the decline of melatonin levels. Another limitation is that we used one single measurement of one-spot morning urinary biomarkers, which may not represent long-term exposure level. Although we had broad information on various covariates and were able to control for possible confounders, we still lacked information on factors such as have sleep disorders or medication use, etc. Finally, the exposures of interest were collected using a questionnaire, which may lead to some recall bias.

Conclusion

Lower morning melatonin-sulfate levels or MT/C ratio were associated with the presence of prostate cancer. In addition, patients with both low MT/C ratios and PSA levels exceeding 10 ng/ml appeared to be far more likely to have prostate cancer and advanced stage disease. Because this is a cross-sectional case-control study, we could not establish a definite causal relationship between urinary MT/C ratio and risk of prostate cancer. Larger prospective cohort studies are needed to verify these findings.

Methods

Study populations

This hospital-based case-control study was conducted at Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH), a medical center in Kaohsiung City, a harbor city located on the southwest coast of Taiwan. Cases were men with incident, histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of prostate with no previous diagnosis of cancer in other sites between January 2011 and April 2014. Each case patient was age-matched (within 2 years) with two healthy men who came in for health check-ups at our Department of Preventive Medicine the same month that the case were recruited after verifying the absence of any neoplastic diseases. The controls had either unremarkable digital rectal exams or remarkable digital rectal exams but histologically confirmed benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Data collection

Overview

Reference date for the cases was defined as date of pathology proof of prostate cancer. Controls were matched within the same month, the reference month. Subjects in both groups answered in-person interviews conducted by trained interviewers using standardized questionnaires collecting socio-demographic information (age, education, and marital status), family history of prostate cancer (PCa) and lifestyle (use of tobacco, alcohol, betel chewing, and vitamin D supplements). The medical charts of all cases were reviewed to collect data on serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level at diagnosis and disease stage. The medical charts of controls were reviewed to collect measured PSA results. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kaohsiung Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital (KMUH-IRB-20110101). All the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Urine sample collection

After their interviews, both case and control subjects provided the first-spot morning urine samples after waking up. The samples were divided into labeled cry-tubes of 4.5 mL volume each and then immediately stored at −20 °C. Urine specimens from case subjects and matched control subjects were handled identically and assayed on the same day and in the same run. All samples were taken out of the freezer simultaneously and sent to the laboratory in the same parcel on dry ice. Laboratory personnel were blinded to the case-control status of all specimens. Analytic error was controlled for by including two standard samples in each assay. The morning urinary measurements showed good sensitivity and specificity in identifying individual differences in nocturnal plasma melatonin levels53.

Assessment of urinary melatonin-sulfate

Urinary melatonin sulfate was measured by solid phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Melatonin Sulfate ELISA Kit, GenWay Biotech Inc., San Diego, USA). Assay sensitivity was 1.0 ng/dL, and the upper limits of intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation ranged 5.2–12.2% and 5.1–14.9%, respectively, at 5.8–204 ng/dL and 12.4–220 ng/dL. Optical density was measured using an automatically photometer (ELx808™ Absorbance Microplate Reader) at 450 nm.

Assessment of urinary cortisol

Urine cortisol was measured by chemiluminescent immunoassay performed on an ADVIA Centaur XP Immunoassay System analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Ltd., Frimley, Camberley, UK). The ADVIA Centaur Cortisol assay is standardized using internal standards manufactured analytically traceable to gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GCMS). Assay sensitivity was 0.2 μg/dL. The upper limits of intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 2.89–3.82% and 1.86–5.45%, respectively, at 3.88–37.15 ng/dL. Urinary creatinine levels were measured by the modified Jaffe reaction. Urinary melatonin-sulfate and cortisol levels were corrected by urinary creatinine levels53,54.

Statistical analysis

Urinary melatonin-sulfate/cortisol (MT/C) ratio was calculated by urinary melatonin-sulfate levels divided by urinary cortisol levels as a basis for measuring the combined impact of melatonin and cortisol levels simultaneously on the prostate cancer. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the differences of urinary biomarkers, including melatonin-sulfate, cortisol, and MT/C ratio, between case and control groups.

In addition, those urinary markers were dichotomized by medians, which were 43.23 ng/mg creatinine for melatonin, 24.06 ng/mg creatinine for cortisol, and 1.76 for MT/C ratio. Unconditional logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between the urinary markers and the risk of prostate cancer. All analyses were adjusted for age at time of questionnaire completion (<65 vs. ≥65 yrs), family history of PCa, personal habits (smoking, alcohol, and betel nut), and PSA level (<10 vs. ≥10 ng/ml). We also categorized cases into localized prostate cancer (stage T1 or T2) and advanced cancer (extra-prostatic stage T3a or higher, N1/M1)55, and used polytomous logistic regression models to determine the risks of developing localized and advanced prostate cancer relative to the control group56. Multiplicative interaction was appraised by fitting polytomous logistic models containing categorical variables, as well as their cross-products. Wald Z-tests for cross-product terms were used to evaluate the significance of multiplicative interaction for each pair of comparison. All statistical operations were performed using the SAS 9.1 statistical package; all P-values were two-sided and considered significant if <0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tai, S.-Y. et al. Urinary melatonin-sulfate/cortisol ratio and the presence of prostate cancer: A case-control study. Sci. Rep. 6, 29606; doi: 10.1038/srep29606 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grant from Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH104-4R65), Institute of Labor, Occupational safety and Health, Ministry of Labor (1003019), the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST103-2314-B-037-004-MY3, 103-2314-B-037-060, and 104-2314-B-037-052-MY3 and MOST104-2314-B-037-012-MY2), Taiwan’s National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX104-10209PI) and Research Center for Environmental Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University (KMU-TP104A34 and KMU-TP104A00). We thank Chao-Shih Chen for data analysis. None of which had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: S.-Y.T., S.-P.H. and M.-T.W. Performed the experiments: S.-Y.T. and S.-P.H. Analyzed the data: S.-Y.T. and B.-Y.B. Prepared Tables and Figure: S.-Y.T. and M.-T.W. Wrote the paper: S.-Y.T. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Blask D., Dauchy R. & Sauer L. Putting cancer to sleep at night. Endocr. 27, 179–188 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski A. Melatonin in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 186–195 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln G. A., Clarke I. J., Hut R. A. & Hazlerigg D. G. Characterizing a mammalian circannual pacemaker. Science 314, 1941–1944 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Gultekin F., Manchester L. C. & Tan D. X. Light pollution, melatonin suppression and cancer growth. J. Pineal Res. 40, 357–358 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung B. & Ahmad N. Melatonin in cancer management: Progress and promise. Cancer Res. 66, 9789–9793 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekbas O. F., Ogur R., Korkmaz A., Kilic A. & Reiter R. J. Melatonin as an antibiotic: New insights into the actions of this ubiquitous molecule. J. Pineal Res. 44, 222–226 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestroni G. J. The immunoneuroendocrine role of melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 14, 1–10 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestroni G. J. & Conti A. Anti-stress role of the melatonin-immuno-opioid network: Evidence for a physiological mechanism involving T cell-derived, immunoreactive beta-endorphin and MET-enkephalin binding to thymic opioid receptors. Int. J. Neurosci. 61, 289–298 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Vico A., Guerrero J., Lardone P. & Reiter R. A review of the multiple actions of melatonin on the immune system. Endocr. 27, 189–200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepanik M. Melatonin and its influence on immune system. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 58, 115–124 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyukavci M. et al. Melatonin cytotoxicity in human leukemia cells: Relation with its pro-oxidant effect. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 20, 73–79 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano I. et al. Pro-oxidant effect of melatonin in tumour leucocytes: Relation with its cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic effects. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 108, 14–20 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schernhammer E. S. & Hankinson S. E. Urinary melatonin levels and postmenopausal breast cancer risk in the Nurses’ Health Study cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 18, 74–79 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schernhammer E. S. et al. Urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin levels and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100, 898–905 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M. et al. Urinary excretion of melatonin and association with breast cancer: Meta-analysis and review of the literature. Breast Care (Basel) 9, 182–187 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. S., Deng Q., Fan W. Y., Wang W. Y. & Wang X. Light exposure at night, sleep duration, melatonin, and breast cancer: a dose-response analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 23, 269–276 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Gonzalez C., Gonzalez A., Martinez-Campa C., Gomez-Arozamena J. & Cos S. Melatonin sensitizes human breast cancer cells to ionizing radiation by downregulating proteins involved in double-strand DNA break repair. J. Pineal Res. 58, 189–197 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. B. et al. Urinary melatonin concentration and the risk of breast cancer in nurses’ health study II. Am. J. Epidemiol. 181, 155–162 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata C. et al. Light exposure at night, urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin, and serum estrogens and androgens in postmenopausal Japanese women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 17, 1418–1423 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2014 (American Cancer Society, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch C., Bartsch H., Fluchter S. H., Attanasio A. & Gupta D. Evidence for modulation of melatonin secretion in men with benign and malignant tumors of the prostate: relationship with the pituitary hormones. J. Pineal Res. 2, 121–132 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir L. G. et al. Circadian disruption, sleep loss, and prostate cancer risk: A systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 21, 1002–1011 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch C. et al. Melatonin and 6-sulfatoxymelatonin circadian rhythms in serum and urine of primary prostate cancer patients: evidence for reduced pineal activity and relevance of urinary determinations. Clin. Chim. Acta 209, 153–167 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu S. Y. W., Leung W. Y., Tam C. W., Liu V. W. S. & Yao K. M. Melatonin MT1 receptor-induced transcriptional up-regulation of p27Kip1 in prostate cancer antiproliferation is mediated via inhibition of constitutively active nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB): Potential implications on prostate cancer chemoprevention and therapy. J. Pineal Res. 54, 69–79 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touitou Y. et al. Adrenal circadian system in young and elderly human subjects: A comparative study. J. Endocrinol. 93, 201–210 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touitou Y. et al. Adrenocortical hormones, ageing and mental condition: Seasonal and circadian rhythms of plasma 18-hydroxy-11-deoxycorticosterone, total and free cortisol and urinary corticosteroids. J. Endocrinol. 96, 53–64 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirick D. K. et al. Night shift work and levels of 6-sulfatoxymelatonin and cortisol in men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22, 1079–1087 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis A. S. et al. Associations of salivary cortisol levels with inflammatory markers: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 1009–1018 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens L. M. & Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420, 860–867 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir L. G. et al. Urinary melatonin levels, sleep disruption, and risk of prostate cancer in elderly men. Eur. Urol. 67, 191–194 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blask D. E., Sauer L. A. & Dauchy R. T. Melatonin as a chronobiotic/anticancer agent: Cellular, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of action and their implications for circadian-based cancer therapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2, 113–132 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Dan Xian Tan, Erren T. C., Fuentes-Broto L. & Paredes S. D. Light-mediated perturbations of circadian timing and cancer risk: A mechanistic analysis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 8, 354–360 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blask D. E. et al. Melatonin-depleted blood from premenopausal women exposed to light at night stimulates growth of human breast cancer xenografts in nude rats. Cancer Res. 65, 11174–11184 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blask D. E., Dauchy R. T., Brainard G. C. & Hanifin J. P. Circadian stage-dependent inhibition of human breast cancer metabolism and growth by the nocturnal melatonin signal: Consequences of its disruption by light at night in rats and women. Integr. Cancer Ther. 8, 347–53 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauchy R. T. et al. Melatonin-depleted blood from healthy adult men exposed to environmental light at night stimulates growth, signal transduction and metabolic activity of tissue-isolated human prostate cancer xenografts in nude rats. Cancer Res. 71, 1324 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Hynes B., Huang W., Reiter R. J. & Ahmad N. Melatonin resynchronizes dysregulated circadian rhythm circuitry in human prostate cancer cells. J. Pineal Res. 49, 60–68 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Hynes B. et al. Melatonin, a novel Sirt1 inhibitor, imparts antiproliferative effects against prostate cancer in vitro in culture and in vivo in TRAMP model. J. Pineal Res. 50, 140–149 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo S. S. & Yoo Y. M. Melatonin induces apoptotic death in LNCaP cells via p38 and JNK pathways: Therapeutic implications for prostate cancer. J. Pineal Res. 47, 8–14 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzer A. et al. Melatonin has no effect on the growth, morphology or cell cycle of human breast cancer (MCF-7), cervical cancer (HeLa), osteosarcoma (MG-63) or lymphoblastoid (TK6) cells. Cancer Lett. 122, 17–23 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirozhok I., Meye A., Hakenberg O. W., Fuessel S. & Wirth M. P. Serotonin and melatonin do not play a prominent role in the growth of prostate cancer cell lines. Urol. Int. 84, 452–460 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck A. & Naray-Fejes-Toth A. Glucocorticoid action In Endocrinology 3rd edn (ed. DeGroot L.) 1642–1654 (W.B. Saunders Co, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Coussens L. M. & Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420, 860–867 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetterbuerg L., Beck-Friis J., Aperia B. & Petterson U. Melatonin/cortisol ratio in depression. Lancet 2, 1361 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier I. N., Johnstone E. C., Crow T. J. & Arendt J. Melatonin/cortisol ratio in psychiatric illness. Lancet 1, 1070 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachon A. Significance of the PSA-concentration for the detection of prostate cancer. Pathologe 26, 469–472 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horchani A. et al. Prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia in general practice and practical approach of the Tunisian general practitioner (Prevapt study). Tunis. Med. 85, 619–624 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A. et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J. Clin. 58, 71–96 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitin T. et al. Diabetes mellitus, race and the odds of high grade prostate cancer in men treated with radiation therapy. J. Urol. 186, 2233–2238 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa A. S. et al. A nomogram for predicting upgrading in patients with low- and intermediate-grade prostate cancer in the era of extended prostate sampling. BJU Int. 105, 352–358 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrate A. et al. Clinical performance of the prostate health index (PHI) for the prediction of prostate cancer in obese men: data from the PROMEtheuS project, a multicentre European prospective study. BJU Int. 115, 537–545 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banez L. L., Albisinni S., Freedland S. J., Tubaro A. & De Nunzio C. The impact of obesity on the predictive accuracy of PSA in men undergoing prostate biopsy. World J. Urol. 32, 323–328 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S. et al. Plateau effect of prostate cancer risk-associated SNPs in discriminating prostate biopsy outcomes. Prostate 73, 1824–1835 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C., Cook M. R., Kavet R., Sastre A. & Smith D. K. Prediction of nocturnal plasma melatonin from morning urinary measures. J. Pineal Res. 24, 230–238 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook M. R. et al. Morning urinary assessment of nocturnal melatonin secretion in older women. J. Pineal Res. 28, 41–47 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Montironi R., Bostwick D. G., Lopez-Beltran A. & Berney D. M. Staging of prostate cancer. Histopathology 60, 87–117 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman K. & Greenland S. Modern epidemiology 2nd edn (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.