Abstract

Skeletal muscle is a highly dynamic tissue that responds to endogenous and external stimuli, including alterations in mechanical loading and growth factors. In particular, the antigravity soleus muscle experiences significant muscle atrophy during disuse and extensive muscle damage upon reloading. Since insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) has been implicated as a central regulator of muscle repair and modulation of muscle size, we examined the effect of viral mediated overexpression of IGF-1 on the soleus muscle following hindlimb cast immobilization and upon reloading. Recombinant IGF-1 cDNA virus was injected into one of the posterior hindlimbs of the mice, while the contralateral limb was injected with saline (control). At 20 weeks of age, both hindlimbs were immobilized for two weeks to induce muscle atrophy in the soleus and ankle plantar flexor muscle group. Subsequently, the mice were allowed to reambulate and muscle damage and recovery was monitored over a period of 2 to 21 days. The primary finding of this study was that IGF-1 overexpression attenuated reloading-induced muscle damage in the soleus muscle, and accelerated muscle regeneration and force recovery. Muscle T2 assessed by MRI, a nonspecific marker of muscle damage, was significantly lower in IGF-1 injected, compared to contralateral soleus muscles at 2 and 5 days reambulation (P<0.05). The reduced prevalence of muscle damage in IGF-1 injected soleus muscles was confirmed on histology, with a lower fraction area of abnormal muscle tissue in IGF-I injected muscles at 2 days reambulation (33.2±3.3%vs 54.1±3.6%, P<0.05). Evidence of the effect of IGF-1 on muscle regeneration included timely increases in the number of central nuclei (21% at 5 days reambulation), paired-box transcription factor 7 (36% at 5 days), embryonic myosin (37% at 10 days), and elevated MyoD mRNA (7-fold at 2 days) in IGF-1 injected limbs (P<0.05). These findings demonstrate a potential role of IGF-1 in protecting unloaded skeletal muscles from damage and accelerating muscle repair and regeneration.

Keywords: IGF-1, skeletal muscle, muscle plasticity, disuse

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle is a highly dynamic tissue, capable of continuous remodelling in response to various environmental stimuli (Adams, 2002). It is widely recognized that conditions of unloading, such as limb immobilization or microgravity, result in the loss of muscle mass and strength (Booth, 1982; Mitchell & Pavlath, 2001; Ye et al., 2012). On the other hand, atrophied muscles can regain their functional performance when returned to normal loading conditions or with training, although this process is often slow and incomplete (Witzmann et al., 1982; Nilsson et al., 2003). Previous investigations have shown that disuse or unloading also renders the muscles more vulnerable to damage. Increased susceptibility to muscle injury has been demonstrated in both unloaded human and animal muscles (Warren et al., 1994; Ploutz-Snyder et al., 1996).

Significant ultrastructural alterations, consistent with muscle damage, have been reported upon reloading or reambulation following an extended period of disuse (Fitts et al., 2000; Kasper et al., 2002). Disruption of cellular muscle membrane integrity, muscle necrosis, sarcomere lesions, and myofibre swelling are visible in hindlimb unloading rodent models within 48 hrs of reloading (Kasper, 1995; Riley, 1998; Dumont et al., 2008). Others have reported tearing of connective tissue, increased macrophages, and phagocytic infiltration within 24–72 hrs following reloading, suggesting a weakening of the extracellular matrix and myofibrils, as well as activation of inflammatory processes (Tidball, 2002). Sarcomere lesions associated with reloading have been primarily observed in rodent slow anti-gravity muscles, such as the soleus and adductor longus (Vijayan et al., 1998). In fact, we previously demonstrated that reloading after cast immobilization induces extensive muscle damage in the murine soleus muscle, while the neighbouring muscles are preserved (Frimel et al., 2005).

Locally produced growth factors play an important role in the removal of necrotic materials in skeletal muscle after insult as well as muscle repair (Adams, 2002; Huard et al., 2002). Although a number of growth factors have the potential to affect muscle repair, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) has been implicated as one of the primary regulators of both muscle regeneration and connective tissue remodelling (Pelosi et al., 2007). Local upregulation of IGF-1 has been observed during muscle repair in a variety of animal models of muscle damage, such as myotoxin injection and eccentric muscle contractions (McKoy et al., 1999; Hill & Goldspink, 2003). It has also been shown that IGF-1 can reduce early myofibre necrosis and protect muscles from contraction-induced damage in dystrophic mdx mice (Barton et al., 2002). Pelosi et al further reported that transgenic overexpression of muscle-restricted IGF-1 (mIGF-1) suppresses proinflammatory cytokines, modulating the inflammatory response and accelerating muscle regeneration following myotoxic injury (Pelosi et al., 2007). To our knowledge, no studies have investigated the effect of IGF-1 on the susceptibility of atrophied muscles to reloading-induced muscle injury.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of IGF-1 overexpression on reloading-induced skeletal muscle damage and subsequent muscle recovery after cast immobilization in the murine soleus muscle, a postural antigravity muscle of the lower hindlimb, which demonstrates extensive muscle damage upon reloading.

Muscle-specific overexpression of IGF-1 was accomplished by injecting a recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) encoding for IGF-1A into the posterior compartment of one hindlimb, targeting the soleus muscle. The contralateral limb received an injection of the same volume of sterile PBS solution. At 20 weeks of age, both hindlimbs of mice were immobilized in a plaster cast for 2 weeks after which the animals were allowed to reambulate for either 2, 5, 10, or 21 days. A combination of in vivo magnetic resonance imaging and in vitro functional and histological measurements were implemented.

METHODS

Animals care and experimental design

All procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 48 female C57BL6 mice (age 3 weeks; Charles River, Inc., Wilmington, Massachusetts) were studied at multiple time points prior to and following cast immobilization. Animals were housed in an accredited animal facility at the University of Florida under a 12 h light–12 h dark cycle, with drinking water and standard chow provided ad libitum.

In order to obtain expression across the entire posterior compartment of the hindlimb, mice were injected at 3 weeks of age, when the muscles were small and undergoing active growth. Under isoflurane anaesthesia (2–3%), the posterior compartment of one hindlimb was injected with 2×1010 viral particles in 85 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). This method of delivery targeted the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles. The contralateral limb received an injection of the same volume of sterile PBS solution. An AAV2/8 self-complimentary vector was constructed, containing a Chicken β-actin promoter/enhancer, the rat IGF-IA cDNA, bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal, and the inverted terminal repeats necessary for viral packaging. The vector was produced by the Vector Core of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. A preliminary study from our lab (n=5 mice) showed that the elevated IGF-1 protein expression (ELISA kit specific for rodent IGF-1, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was localized to the posterior compartment of the hindlimb for up to at least 6 months (Gastrocnemius (ng/g): IGF-1 injected: 74.0±10.1; PBS injected: 4.3± 1.2, Soleus (ng/g): IGF-1 injected: 18.1±2.1; PBS injected: 6.3± 0.8) and no significant increase in serum IGF-1 was detected (serum: 225± 19 ng/ml for IGF-1 injected; 216± 26 ng/ml for wildtypes). After injection, mice were returned to their cages and maintained normal activity for the next four months.

Four months after injection, when the mice were adult they were randomly assigned into six groups (n=8 for each condition): 1) non-casted; 2) two weeks of cast immobilization (2 wk Immob); 3) two days of reambulation (2d Reamb); 4) five days of reambulation (5d Reamb); 5) ten days of reambulation (10d Reamb); and 6) twenty-one days of reambulation (21d Reamb). The procedure of cast immobilization and reambulation are described below.

Cast Immobilization and reambulation

Briefly, the mice were anaesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane. A plaster of Paris cast which encompassed both hindlimbs and the caudal fourth of the body (superior to the wings of the ilium) was applied while the mouse was anesthetized. The hindlimbs were positioned with the hip and knee joints extended and the ankle plantarflexed (~160°), putting the posterior compartment muscles (soleus, gastrocnemius and plantaris) in a shortened position in order to maximize atrophy. The mice were able to move freely in the cage using their forelimbs and reach their food and water. The mice were checked daily for abrasions, venous occlusion and faecal clearance. Following two weeks of cast immobilization, the casts were removed and mice were euthanized or allowed to reambulate in their cages for 2, 5, 10 or 21 days.

Magnetic resonance imaging

In vivo MRI was performed to assess longitudinal changes in the size of the ankle plantar flexor muscle group (medial and lateral gastrocnemius, soleus and plantaris muscles) (Zhang et al., 2008), as well as to noninvasively monitor muscle damage/inflammation. MRI was implemented at repeated time points after injection, then after 2 weeks of cast immobilization as well as during reambulation (2, 5, 10, and 21 days) using a horizontal, 4.7 Tesla magnet with Paravision 3.0.2 software (Bruker Medical, Ettlingen, Germany) and a custom-built solenoid 1H-coil with a 2.0-cm internal diameter. Mice were anesthetized with 1–1.5% isoflurane for the duration of the MR experiment. Heart rate, oxygen saturation, respiration rate and body temperature were continuously monitored throughout the MR experiment.

To measure alterations in muscle size 3D gradient-echo images were acquired with an encoding matrix of 384 × 192 × 64, field of view of 1.65 × 1.2 × 2.4 cm, pulse repetition time (TR) of 100 ms, and an echo time (TE) of 7.5 ms. The total region imaged extended from the mid-thigh to the calcaneus. Cross-sectional area (CSA) of the ankle plantar flexors was manually outlined using Osirix software (http://www.osirix-viewer.com/). The average of the three consecutive slices with the largest CSAs was recorded as the maximal CSA (CSAmax).

The occurrence of muscle damage during reloading was monitored noninvasively in the mouse lower hindlimb muscles using T2-weighted imaging. Endogenous MR transverse relaxation properties (T2) of skeletal muscle provide a sensitive in vivo marker of muscle damage/inflammation and have been used extensively to study both mechanical and chemical disruption of the sarcolemmal membrane (Foley et al., 1999; Frimel et al., 2005). T2-weighted, multiple slice, single spin-echo images of the lower hindlimb were acquired with the following parameters: TR = 2,000 ms, TE = 14 and 40 ms, FOV = 10–20 mm, slice thickness 1 mm, acquisition matrix = 128 × 256 and two signal averages (Evans et al., 1998). Mean T2 values and the percentage of damaged muscle (or percentage of pixels with elevated T2 values -defined as two standard deviations above the mean of controls) in the soleus muscles were quantified using in-house software with Interactive Data Language (IDL).

In vitro force mechanics

Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation while under anaesthesia, in vitro force mechanics was performed on isolated soleus muscles at each experimental time point as previously described. Briefly, soleus muscles were immersed horizontally in a bath of Ringer’s solution at 25°C and equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH= 7.4. The distal tendon was tied to a nonmovable post and the proximal tendon attached to an isometric force transducer (Aurora Scientific, Inc., Aurora, Ontario, Canada) (Barton, 2006). The bathing solution was pumped through a separate temperature controller (Isotemp, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc) and back into the bath to maintain a constant temperature of 25°C. Optimal muscle length was defined as the length that resulted in the maximum twitch tension. Subsequently, maximal isometric tetanic force was assessed using supramaximal electrical pulses (20~30 V, 80 Hz, 1500 msec duration) at the optimal length (Grass S88 stimulator; West Warwick, RI). Stimulation was delivered via two parallel platinum electrodes that were positioned along the length of the muscle. Specific force was calculated by normalizing maximal tetanic force to the physiological cross-sectional area (CSA) and expressed in N/cm2. The physiological CSA of soleus muscle was determined according to equation shown below: where θ = angle of pennation, 6° for the soleus muscle; ρ = density of mammalian skeletal muscle (1.06 g/cm3); soleus fibre length= optimal length× 0.71 (Brooks & Faulkner, 1991).

At the end of the mechanical measurements, soleus muscles were weighed, pinned onto foam board at optimum length with optimal cutting temperature compound, and frozen on top of melting isopentane, pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Fibre morphology and immunohistochemistry

Transverse muscle sections (10 μm thick) were cut from the mid-belly of the soleus and mounted serially on gelatin-coated glass slides. Muscle sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for examination of central nuclei. Immunohistochemistry was used on serial sections to assess the distribution of embryonic myosin and the paired box transcription factor family member Pax7. Primary antibodies were rabbit anti-laminin (Neomarker Labvision, Fremont, CA), mouse anti-embryonic myosin MHC (DSHB, Iowa city, IA), mouse anti-Pax7 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Secondary antibodies were rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Nordic Immunological Laboratories, Westbury, NY) and Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). A mouse blocking kit (BMK-2202, Mouse on Mouse, Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA) was used in staining of Pax7. Sections were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector lab, Burlingame, CA). Image acquisition was performed on a Leitz DMR microscope with a digital camera (Leica Microsystems, Solms, Germany). NIH Image J (version 1.62; http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) was used to analyze the data. The pixels setting used for conversion of pixels to micrometer were 1.50 pixels- 1μm2 for a 10X objective. The percentage of positive muscle fibres was quantified from a sample of 150–250 fibres on randomly selected slides in a blinded way.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and TaqMan quantitative real-time PCR analysis

RNA was isolated from homogenized soleus muscles using the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was quantified using a Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, ND Software version 3.3.0). One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using a commercially available kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis for RT-PCR, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time PCR was performed for the following using TaqMan PCR master mix and gene expression primers that are inventory items of Applied Biosystems: MyoD (assay ID: Mm00440387_m1) and 18 s (4352339E). Each sample was run in duplicate. The relative quantification method (ΔΔCT, where CT is threshold cycle) was used to document results, and data were normalized to 18 s controls.

Data analysis

Using SPSS software (version 16.0), two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the main effects of injection and loading and the interaction of the main effects. Paired t-tests were used for comparisons between IGF-1 injected and contralateral, PBS injected limbs at each time point. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare all variables within the same injection group. Post-hoc testing for ANOVAs measures was performed using a Bonferroni test. A significance level of p<0.05 was used for all comparisons. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Muscle size and mass

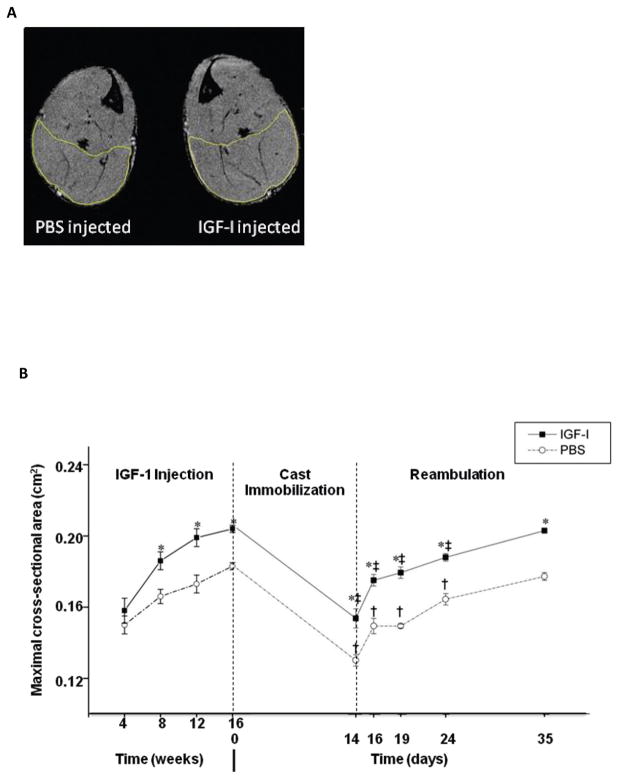

Longitudinal MR measurements of the CSAmax of the ankle plantar flexors show significant hypertrophy in the IGF-1 injected hindlimb of young adult mice, compared to the contralateral control (Fig. 1, p<0.05). The relative difference in CSAmax between IGF-1 and PBS injected limbs was maintained after 2 weeks of cast immobilization and during reambulation (Fig. 1). The changes in ankle plantar flexor CSAmax during cast immobilization and reloading were consistent with the findings in soleus muscle wet weights (Table 1). The soleus muscle in the IGF-1-injected limb was, on average, 19% larger than contralateral muscles prior to cast immobilization. After two weeks of cast immobilization, there was a decrease in the mass of the soleus in both IGF-1 and PBS-injected limbs (~20%).

Figure 1.

MR images of lower hindlimb muscles and ankle plantarflexors maximal cross-sectional area (CSAmax). A) Representative trans-axial MRIs of the mouse lower hindlimb with IGF-1 injection in one lower hindlimb and PBS injection in the contralateral side prior to cast immobilization (at 20 weeks of age; 16 weeks post-injection). Muscle CSAmax was determined by manually outlining the ankle plantarflexors muscles. B) CSAmax of the ankle plantarflexors. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *denotes significant difference (p<0.05) between IGF-1 injected and PBS injected group. † indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from the noncasted group in the PBS injected muscles. ‡ indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from noncasted group in the IGF-1 injected muscles.

Table 1.

In vitro soleus contractile properties

| Wet Weight (mg) | Tetanic Force (mN) | Specific force (N/cm2) | Twitch Force (mN) | TPT (ms) | RT1/2 (ms) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| IGF-1 | PBS | IGF-1 | PBS | IGF-1 | PBS | IGF-1 | PBS | IGF-1 | PBS | IGF-1 | PBS | |

| Noncasted | 10.43 ± 0.38* | 8.80 ± 0.36 | 218.1 ± 5.5* | 187.7 ± 6.1 | 18.4 ± 1.8 | 18.0 ± 1.6 | 44.1 ± 4.6* | 37.3 ± 3.3 | 46.4 ± 1.4* | 52.3 ± 1.7 | 65.3 ± 2.2 | 64.6 ± 2.6 |

| 2wk Immob | 8.49 ± 0.21*‡ | 7.05 ± 0.21† | 143.0 ± 8.2*‡ | 117.5 ± 11.5† | 11.6 ± 0.9‡ | 11.0 ± 1.1† | 34.8 ± 2.7 | 34.0 ± 3.7 | 50.6 ± 1.8 | 49.4 ± 3.5 | 77.4 ± 5.7 | 79.1 ± 6.4 |

| 2d Reamb | 10.96 ± 0.50* | 8.96 ± 0.52 | 112.9 ± 6.6*‡ | 84.5 ± 9.1† | 8.2 ± 0.6‡ | 7.4 ± 0.8† | 33.9 ± 4.6 | 30.1 ± 3.7 | 57.0 ± 3.8 | 58.9 ± 4.8 | 74.6 ± 5.1 | 81.9 ± 4.5† |

| 5d Reamb | 10.82 ± 0.23* | 9.62 ± 0.09 | 156.5 ± 10.1*‡ | 118.9 ± 7.6† | 12.1 ± 1.0‡ | 10.5 ± 0.8† | 42.2 ± 4.1 | 34.0 ± 3.4 | 53.7 ± 1.6 | 57.2 ± 1.6 | 67.3 ± 1.7 | 73.6 ± 2.8 |

| 10d Reamb | 11.26 ± 0.32* | 9.70 ± 0.22 | 195.3 ± 8.3* | 142.2 ± 8.3† | 14.5 ± 0.6*‡ | 12.1 ± 0.5† | 54.4 ± 3.8* | 39.4 ± 2.6 | 49.1 ± 2.0 | 53.4 ± 2.7 | 62.8 ± 3.0 | 66.0 ± 2.0 |

| 21 Reamb | 10.95 ± 0.33* | 9.59 ± 0.17 | 231.5 ± 6.5* | 193.3 ± 4.0 | 19.9 ± 0.9 | 18.1 ± 0.6 | 50.3 ± 3.7 | 45.2 ± 1.6 | 47.0 ± 3.3 | 49.3 ± 1.5 | 58.8 ± 4.8 | 64.3 ± 3.0 |

Values are expressed as means ± SEM.

denotes significant difference (p<0.05) between IGF-1 injected and PBS injected group.

indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from the noncasted group in the PBS injected muscles.

indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from noncasted group in the IGF-1 injected muscles. An interaction of group (IGF-1 injected vs PBS injected) and time was detected where IGF-1 injected muscles had a significantly higher increase in tetanic force (not indicated on figure) (p<0.05). (p<0.05).

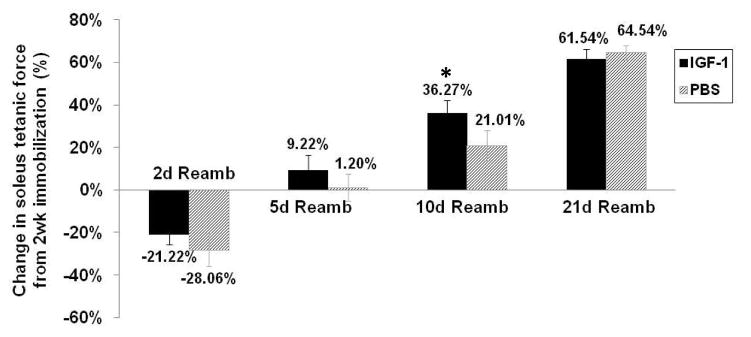

Recovery of contractile properties

The maximum tetanic force generated by isolated soleus muscles at different time points is shown in Table 1. Following two weeks of cast immobilization, the maximum force generated by both sets of muscles declined by approximately 35%, but the IGF-1-treated muscles still generated 22% more force than controls. After 2 days of reambulation, the forces generated by both sets of muscles were further reduced. During the next 2 to 21 days of reambulation maximal force progressively increased in both treated and untreated muscles (Figure 2). However, the recovery in muscle strength tended to occur faster in IGF-1 injected muscles, as demonstrated by larger proportional changes in force production at 5 and 10 days reambulation shown in Table 1. As a consequence, at 10 days reambulation specific force production was significantly higher in IGF-1 injected muscles (9.2±0.3 N/cm2) compared to PBS injected muscles (7.7±0.3 N/cm2; p<0.05, Table 1). At this time, IGF-1 injected limbs had recovered to pre-immobilization values (maximum force: 218.1± 5.5 mN), while PBS-injected limbs reached 75.7% of pre-immobilization values.

Figure 2.

Soleus muscle in vitro force generation prior to, after immobilization and during reambulation. Percent change in soleus tetanic force by comparison with 2 wk Immob at different reambulation time points. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *denotes significant difference (p<0.05) between IGF-1 injected and PBS injected group.

The time-dependent twitch parameters were assessed by determining the time to peak tension (TPT) and half relaxation time (RT1/2) to test the effect of IGF-1 on twitch kinetics. TPT was significantly shortened in IGF-I injected (46.4±1.4 ms) compared to PBS injected (52.3±1.7 ms) mice prior to cast immobilization, but not after immobilization or during reambulation. There was no difference in half relaxation time between the two groups at any of the time points.

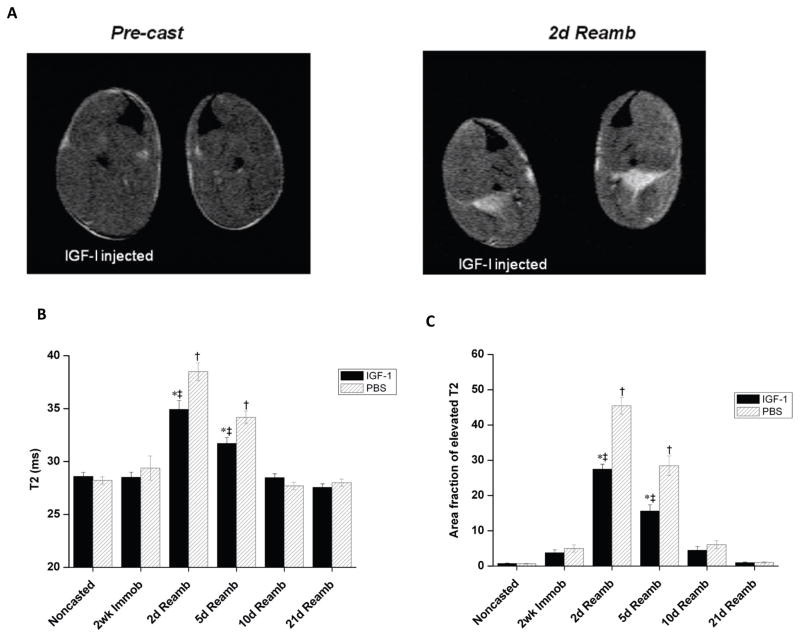

Assessment of muscle damage using MRI and histology

Reloading induced muscle damage was assessed noninvasively using T2-weighted (T2w) MR images acquired from mouse hindlimbs injected with either IGF-1 or PBS. Representative T2w MR images obtained at 2 weeks cast immobilization and 2 days reloading are shown in Fig. 3A. Quantitative T2 values obtained at the different time points are presented in Figs. 3B and 3C. In all animals, a homogeneous signal intensity and normal T2 values were observed prior to and after 2 weeks of cast immobilization. Upon reambulation (2 and 5 days) the soleus muscle became hyper-intense (i.e. brighter) on T2w images and showed a dramatic elevation in muscle T2, consistent with muscle damage. Both mean muscle T2 and the area fraction of muscle T2 was however significantly lower in IGF-1 injected muscles, compared to contralateral control limbs, at both 2 and 5 days reambulation, indicating less severe muscle damage (Fig. 3B and 3C).

Figure 3.

T2-MRI of reloading induced muscle damage in the soleus muscle. A) Representative T2 images (TE=40 ms) from the mice lower hindlimb muscles acquired prior to 2 weeks cast immobilization and 2 days reambulation. B) Muscle T2 of the soleus muscle at different time points. C) Percentage of pixels with elevated T2 (% damaged muscle) in the soleus muscle of mice at different time points. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *denotes significant difference (p<0.05) between IGF-1 injected and PBS injected group. † indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from the noncasted group in the PBS injected muscles. ‡ indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from noncasted group in the IGF-1 injected muscles.

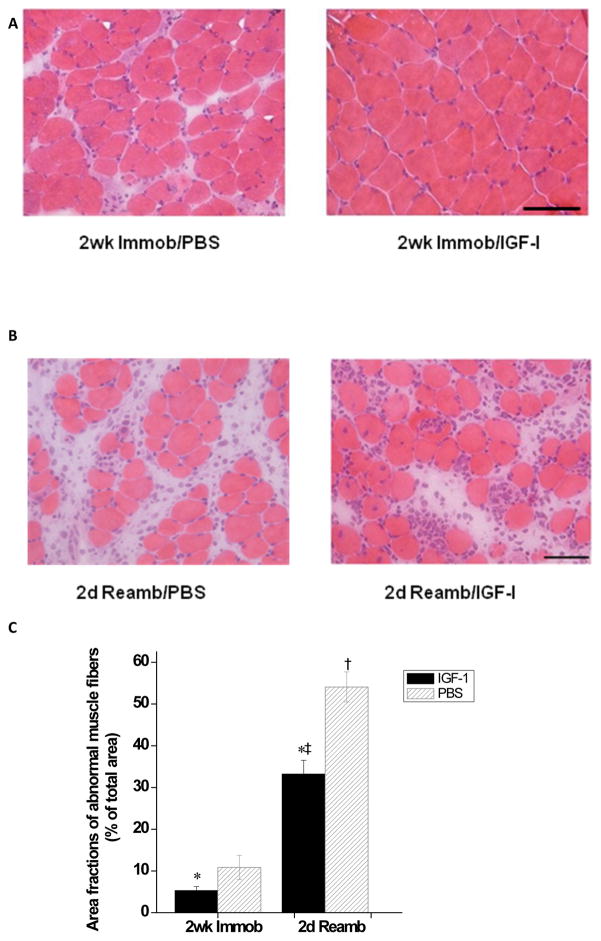

These results were confirmed by examining H&E-stained soleus cross sections using a 63-point counting scale, as described by Weibel et al [27] (Fig. 4). The fractional area occupied by abnormal tissue (including inflammatory cells, swollen or necrotic fibres and widened interstitial space) was significantly elevated in PBS- vs. IGF-I-injected limbs. The latter effect was observed following both immobilization (2 wk Immob: 10.9±2.9% in PBS- versus 5.3±1.0% in IGF-injected, p < 0.05) and reambulation (2d Reamb: 54.1±3.6% in PBS- versus 33.2±3.3% in IGF-injected, p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Histology of the soleus muscle after cast immobilization and reloading-induced muscle injury. A) Light micrographs of H&E-stained cross-sections of the soleus from both IGF-1- (Right) and PBS- (Left) injected groups following 2 weeks of cast immobilization. B) Representative H&E-stained cross-sections of the soleus at 2 days of reloading following cast immobilization in IGF-1- and PBS-injected groups. C) Area fractions of abnormal muscle in the IGF-1 and PBS injection group. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *Denotes significant difference (p<0.05) between IGF-1 injected and PBS injected group. † indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from the casted group in the PBS injected muscles. ‡ indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from casted group in the IGF-1 injected muscles. Bar=50μm.

Markers of muscle regeneration

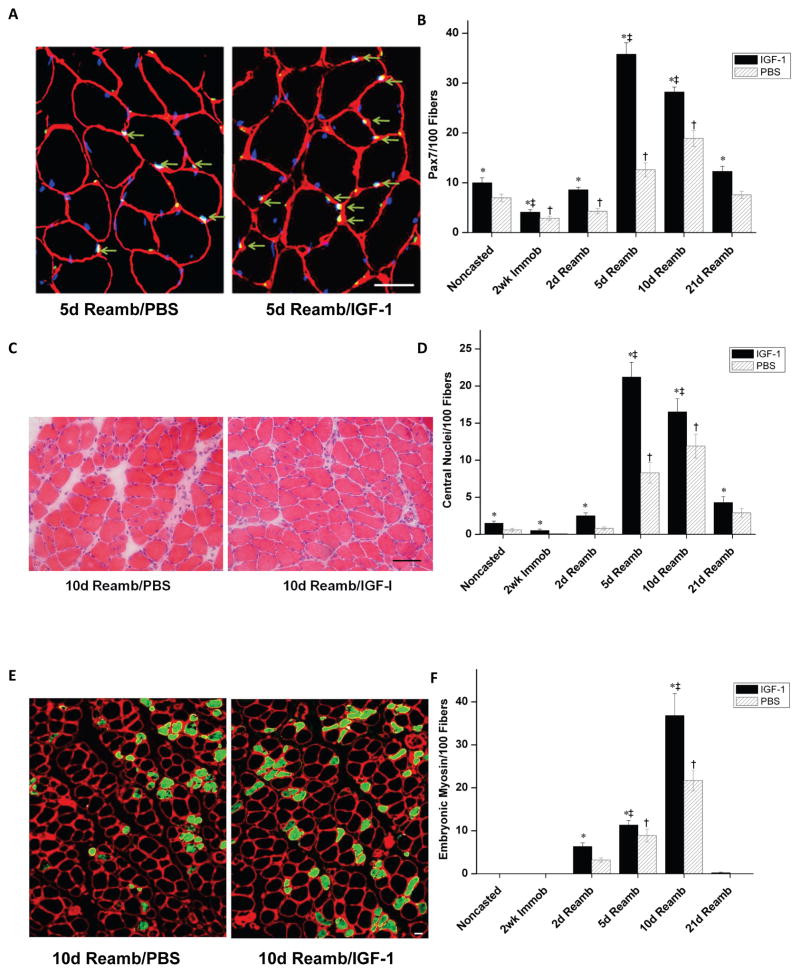

The effects of local overexpression of IGF-1 on various measures of soleus muscle regeneration were determined prior to, following cast immobilization, and during reambulation. Markers of muscle regeneration included number of paired-box transcription factor 7 (Pax7)-positive muscle fibres, percentage of central nuclei, and number of muscle fibres expressing embryonic myosin. Pax7 is expressed by quiescent, active, and proliferating satellite cells, and these cells are important for muscle regeneration (Relaix et al., 2005). A large increase in the number of Pax7 positive fibres at days 5 and 10 following reambulation was observed using immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5A & B). More importantly, IGF-1 injected muscles showed both an accelerated time course and increased number of Pax7 positive fibres (IGF-1- vs PBS-injected: 35.8±2.3% vs.12.6±1.4% at 5d Reamb, 28.2±1.0% vs.18.9±1.6% at 10d Reamb, respectively, p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Markers of regeneration in the soleus across all experimental timepoints. A) Cross-sections of the soleus muscle stained with laminin (red) + DAPI (blue) + Pax7 (green). Pax7 positive fibres (arrows) at 5 days of reloading. Bar=12.5μm. B) Percentage of Pax7 positive fibres at each time point. C) Light microscopy of H&E-stained myofibres with central nuclei at 10 days of reloading. Bar=50μm. D) Percentage of central nuclei at each time point. E) Cross-sections of the soleus muscle stained with monoclonal antibody against embryonic myosin isoform (green) at 10 days of reloading. Bar=12.5μm. F) Number of fibres expressing embryonic myosin per 100 fibres. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *denotes significant difference (p<0.05) between IGF-1 injected and PBS injected group. † indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from the noncasted group in the PBS injected muscles. ‡ indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from noncasted group in the IGF-1 injected muscles. An interaction of group (IGF-1 injected vs PBS injected) by time was detected where IGF-1 injected muscles had a significantly greater increase in Pax7 and central nuclei positive fibres (not indicated on Figure), p<0.05.

In order to further examine the effects of IGF-1 on muscle regeneration, the percentage of muscle fibres with central nuclei and the number of fibres expressing embryonic myosin were measured (Foley et al., 1999). As shown in Fig. 5C &D, the percentage of central nuclei at 5 and 10 days following reambulation was 13 to 20 fold greater compared with baseline in muscles from PBS-injected hindlimbs. Importantly, both the percentage of central nuclei and embryonic positive fibres was significantly higher in IGF-1 injected muscles than in muscles from PBS-injected limbs (p<0.05). Increases in the number of muscle fibres expressing embryonic myosin were observed at 2, 5 and 10 days reambulation, with the most prevalent increases at 10 days (Fig. 5E&F). The greatest difference in embryonic myosin-positive fibres between the two sets of muscles was observed at 10 days of reambulation, when new muscle fibres are formed (Gorza et al., 1983). Collectively these results demonstrate that overexpression of IGF-1 boosts and accelerates the regenerative response in skeletal muscle.

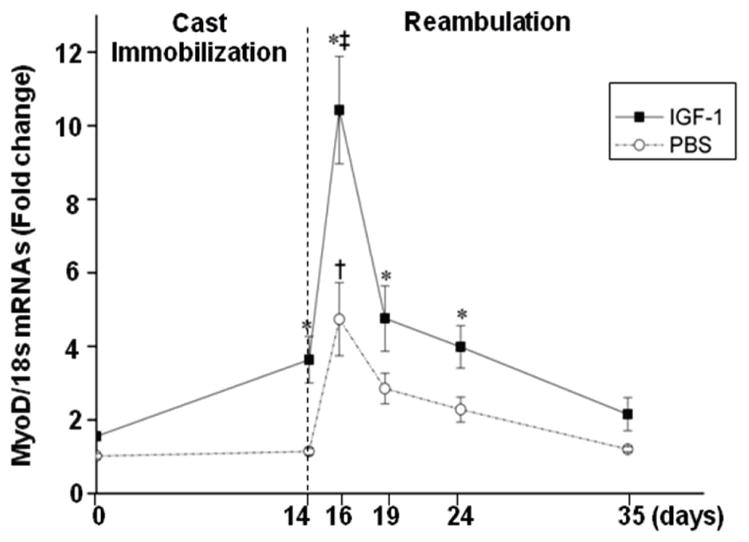

The processes involved in muscle regeneration, including the determination of the myogenic fate of satellite cells, are regulated by transcription factors. Among them, MyoD is the most important one. Therefore, the effects of local overexpression of IGF-1 on the levels of MyoD mRNA were measured at various time points (Fig. 6). MyoD mRNA expression increased 4-fold between the end of cast immobilization and 2 days reambulation, and then progressively declined in muscles from PBS-treated hindlimbs. Peak expression of MyoD mRNA in IGF-1-treated muscles also occurred at 2 days reambulation, however the increase was significantly (p<0.05) greater (7-fold from baseline) in IGF-1 injected muscles compared to contralateral controls. These data indicate that local overexpression of IGF-1 in the soleus leads to an increase in MyoD mRNA levels and plays a role in the regulation of muscle regeneration. Interestingly, there was a significant increase in MyoD with cast immobilization prior to reambulation in the IGF-1 treated soleus muscles (p<0.05), which was not observed in the PBS injected muscle.

Figure 6.

MyoD mRNAs expression in the soleus prior to, after immobilization, and during reambulation. Signal intensity of the mRNA bands was normalized to 18 s. Values are expressed as means ± SEM.*denotes significant difference (p<0.05) between IGF-1 injected and PBS injected group. † indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from the noncasted group in the PBS injected muscles. ‡ indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from noncasted group in the IGF-1 injected muscles.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the impact of local overexpression of IGF-1 on the mouse anti-gravity soleus muscle, a muscle known to demonstrate significant muscle atrophy during disuse and extensive muscle damage upon reloading. The primary finding of this study was that IGF-1 overexpression attenuated reloading-induced muscle damage in the soleus muscle and enhanced the regenerative response. IGF-1 overexpression also appeared to have a positive effect on the maintenance of muscle fibre morphology during cast immobilization, and accelerated the recovery of muscle force. Finally, IGF-1 overexpressing soleus muscles were 15–20% larger at all time points, independent of the loading condition.

Immobilization-induced muscle atrophy is caused by multiple mechanisms, including a decrease in the rate of protein synthesis (Booth, 1987), increased protein degradation (Thomason et al., 1989), elimination of myonuclei (Smith et al., 2000), and loss of satellite cells (Mitchell & Pavlath, 2004). During an extended period of disuse muscles also experience weakening of the extracellular matrix and myofibrils (Riley et al., 1992), leaving slow twitch antigravity muscles particularly vulnerable to reloading-induced muscle damage (Frimel et al., 2005). In this study marked muscle damage was observed in the soleus after two and five days of cage restricted reambulation following cast immobilization, as evidenced by 1) histological and structural abnormalities, 2) a drop in muscle force, and 3) a shift in MR T2 relaxation properties. These results are consistent with previous reports of eccentric contraction like lesions in slow antigravity muscles upon reloading (Warren et al., 1994; Vijayan et al., 1998).

Overexpression of IGF-1 reduced reloading-induced muscle damage following cast immobilization in the soleus as shown by both T2-weighted MRI and histology. It is not clear whether the injury mitigating effect of IGF-1 primarily occurs during reloading, by modulating the inflammatory response and protecting against oxidant damage, or prior to reloading (during unloading) by reducing susceptibility to sarcolemmal damage. It has been shown that muscle injury is intimately linked to inflammation, and the interactions between IGF-1 and proinflammatory cytokines have been reported to be important in predicting the inflammation process and its outcomes (Lang et al., 2001; Adams, 2002). Pelosi et al (Pelosi et al., 2007) demonstrated that treatment with IGF-1 leads to a shorter period of inflammation following cytotoxic muscle injury by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines. IGF-1 may also protect the muscle from oxidant-induced injury during reloading (Hammers et al., 2008) by inhibiting hypoactive mutant superoxide dismutase (Schertzer et al., 2006), although Brocca et al. reported that oxidative stress is not a major player in hindlimb unloading (Brocca et al., 2010). Alternatively, IGF-1 may act during unloading and reduce the susceptibility of atrophic muscle to reloading-damage by minimizing the deleterious effects of muscle unloading (cast immobilization). Histological abnormalities indicative of muscle degeneration (area fraction of abnormal muscle tissue) after two weeks of cast immobilization were less severe in the IGF-1 injected soleus compared to PBS injected muscles. High levels of IGF-1 in young mdx mice, the murine model of muscular dystrophy, also have been shown to protect myofibres from necrosis and preserve muscle function, while elevating signalling pathways associated with muscle survival (Schertzer et al., 2006).

Another important finding in this study is that IGF-1 overexpression boosts the regenerative response of the soleus muscle after 2 weeks cast immobilization and reloading. Because skeletal muscle is a post-mitotic tissue, a progenitor cell group is necessary for regeneration to occur. IGF-1 is well known to be involved in the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of satellite cells (Hill & Goldspink, 2003; Mourkioti & Rosenthal, 2005). In our study, a greater number of paired-box transcription factor (Pax7)-positive fibres, central nuclei, and embryonic myosin-positive fibres were observed throughout the 21 days of reambulation, providing strong evidence for an enhanced regenerative response in muscles overexpressing IGF-1. Furthermore, the peak increases were not only greater in magnitude, but they occurred sooner in IGF-1-treated muscles (Pax7 and central nuclei peaked at 5 days reambulation) compared to PBS-injected muscles.

The accelerated resolution of damage and onset of regenerative processes in the soleus overexpressed with IGF-1 may in part be caused by IGF-1 interactions with MyoD. MyoD, a myogenic regulatory factor, is thought to be essential for muscle regeneration and its expression has been shown to be increased after spinal cord injury, exercise and hindlimb suspension (Dupont-Versteegden et al., 1998; Jayaraman et al., 2012). Our results show a dramatic increase in MyoD expression after cast immobilization, which reaches a peak two days after the beginning of reloading. We also showed that IGF-1 leads to a significant increase in the mRNA expression of MyoD, during both reloading and cast immobilization. One possible explanation for our results is that IGF-1 creates a pool of resting satellite cells already committed to the myogenic program during the unloading condition, which may alleviate some of the deleterious effects of immobilization on the satellite cell regenerative capacity. Thus, it appears as though IGF-1 acts early in the regeneration process potentially by increasing MyoD expression, activating satellite cells, and ultimately enhancing healing from reloading induced injury and cast immobilization.

In vitro force mechanics showed an accelerated rate of functional recovery in muscles overexpressing IGF-1. As expected, a significant drop in force production was observed with cast immobilization and upon reloading in both muscle groups. Decreases in muscle strength have been noted to occur at the point when ultrastructural signs of injury are observed (Pottle & Gosselin, 2000; Frenette et al., 2002). At 10 days of reambulation maximal force production in IGF-1 injected limbs had recovered to 89.5% (p>0.05) of pre-immobilization compared to 75.7% in PBS-injected limbs (p<0.05). We also noted a higher specific force in IGF-1 injected limbs compared to contralateral muscles at 10d reambulation (p<0.05). Accelerated functional recovery in the presence of high IGF-1 levels has been reported following other injury models. Specifically, Pelosi et al showed a higher tetanic force production in MLC/mIGF-1 compared to wild-type animals at 15 days post- cardiotoxin induced injury (Pelosi et al., 2007). The accelerated force production in MLC/mIGF-1 animal was associated with improved muscle regeneration and modulation of connective tissue remodeling.

The anabolic effect of IGF-1 overexpression on skeletal muscle has been demonstrated in a number of animal models (Adams & McCue, 1998; Criswell et al., 1998). In this study we demonstrated increased muscle growth in both the soleus and ankle plantar flexor muscle group following injection of recombinant AAV rat IGF-1 cDNA into the posterior compartment of the lower hindlimbs of 3 week old mice. At 20 weeks of age, IGF-1 injected soleus muscles were on average 19% larger compared to the contralateral muscles and produced 16% more force. This is consistent with previous studies using viral delivery of the IGF-1 construct, with reported increases in muscle mass in healthy animals of between 10 and 20% (Barton-Davis et al., 1999; Stevens-Lapsley et al., 2010). Interestingly, the relative gains in muscle weight and plantar flexor CSAmax observed under normal loading conditions were maintained during cast immobilization and throughout the 21 days of reambulation. Using a combination of in vivo and in vitro methods we could not detect differences in either the rate of atrophy or recovery of muscle mass. The apparent inability of high IGF-1 levels to protect skeletal muscle from disuse atrophy has been reported previously (Criswell et al., 1998; Stevens-Lapsley et al., 2010). Criswell et al demonstrated that the hindlimb muscles of transgenic mice overexpressing IGF-1 experienced the same rate of atrophy in the hindlimb muscles compared to wild type mice (Criswell et al., 1998). Similarly, we found that viral induced IGF-1 overexpression did not attenuate the rate of atrophy in the EDL muscle during cast immobilization (Stevens-Lapsley et al., 2010). In contrast, high IGF-1 levels have proven effective in ameliorating muscle atrophy induced by glucocorticoids (Schakman et al., 2005), indicating that the protective effect of IGF-1 may be dependent on the source of atrophy.

Although IGF-1 overexpression clearly has a positive effect on muscle regeneration in the soleus, we did not observe an increase in the rate of muscle mass recovery upon reloading. We found a similar discrepancy between high IGF-1 levels, muscle regeneration and recovery of muscle mass in the EDL muscle after cast immobilization; although the EDL of IGF-1 injected muscles showed modest gains. We initially speculated that the minimal effect of IGF-1 on the recovery of muscle mass in the EDL muscle was linked to the fact that the EDL is not a primary antigravity muscle in murine animals, and hence experiences a limited amount of (re)loading and myogenic trigger. The data in this study refute this argument as the soleus muscle experiences significant loading during reambulation, as demonstrated by the presence of reloading induced muscle injury on histology and T2-MRI. Alternatively, while it is well demonstrated that IGF-1 plays a critical role in muscle growth and development (Florini et al., 1996; Clemmons, 2009), IGF-1 may not serve as the primary regulator of muscle growth with increased mechanical loading (Spangenburg et al., 2008). Spangenburg et al, using an animal model which expressed a dominant negative IGF-I receptor, showed that increased mechanical load can induce muscle hypertrophy and activate the Akt and p70s6k without a functioning IGF-1 receptor. These experiments suggest that IGF-1 may not be required to activate Akt-mTOR-mediated muscle hypertrophy. Alternatively it is possible that other confounding factors, such as binding proteins, may interfere with the positive effects of IGF-1 overexpression during reloading.

While this study provides valuable information on the potential protective role of IGF-1 during immobilization and subsequent reloading, there are some limitations. First, the contralateral limb was injected with PBS instead of a blank or scrambled AAV virus. Previous studies (Fisher et al., 1997; Woo et al., 2005) have shown that recombinant AAV vectors that do not contain viral protein-coding sequences induce neither cellular nor humoral response in the muscles. Second, the virus promoter used in this study was not muscle-specific, and may have affected other cell types. Finally, we did not examine changes in fibre type composition. Lynch (Lynch et al., 2001) previously reported that IGF-1 production increases the proportion of fast oxidative-glycolytic fibres in healthy animals. In our study, we noted a shortening of the force contraction time prior to immobilization, potentially supporting Lynch’s earlier work. However, we did not detect a significant change in the half-relaxation time.

In summary, our findings indicate that rAAV-IGF-1 overexpression reduces reloading-induced muscle damage in the soleus muscle after cast immobilization, and accelerates muscle regeneration and functional recovery in a young rodent animal model. IGF-1 overexpressing muscles also demonstrated maintenance of muscle fibre morphology during cast immobilization, which may be caused by the effect of IGF on muscle fibres directly or the reported effect of IGF-1 on other tissues, such as connective tissue. Although this model may not directly be applicable to studies on humans, it provides relevant information about the biological action of IGF-1 during reloading and disuse. While it is unlikely that gene therapy will be implemented as a treatment for muscle preservation in the near future, pharmaceutical strategies to promote IGF-1 levels, such as IGFBP-3 conjugates may provide similar benefits.

New Findings.

a) What is the central question of this study?

IGF-1 promotes muscle hypertrophy although no studies have investigated the effect of IGF-1 on the susceptibility of atrophied muscles to reloading-induced muscle injury.

b) What is the main finding and what is its importance?

We employed a comprehensive set of methods including muscle physiological measurements, molecular biology techniques, and non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The results concurrently demonstrate that local overexpression of IGF-1 in a primary antigravity muscle attenuates the muscle from reloading-induced muscle damage and accelerates muscle regeneration and functional recovery following cast immobilization. These findings add new physiological significance to the benefits of IGF-1 on skeletal muscle mass and force generation during varied loading conditions.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Philip R. Miles for reviewing and editing our manuscript and Katherine High, MD for the vector production. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01HD042955, R01HL78670 and P01 HD059751 to G.A.W., H.L.S. and K.V.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conception and design of experiments: F.Y., G.A.W., H.L.S. and K.V. Data collection and analysis: F.Y., S.M., M.L., S.E.B., G.A.W., H.L.S. and K.V. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: F.Y., S.M., M.L., S.E.B., G.A.W., H.L.S. and K.V. All the authors approved the final version for publication. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Adams GR. Invited Review: Autocrine/paracrine IGF-I and skeletal muscle adaptation. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1159–1167. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01264.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams GR, McCue SA. Localized infusion of IGF-I results in skeletal muscle hypertrophy in rats. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1716–1722. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.5.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton-Davis ER, Shoturma DI, Sweeney HL. Contribution of satellite cells to IGF-I induced hypertrophy of skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999;167:301–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton E, Morris L, Musaro A, Rosenthal N, Sweeney H. Muscle-specific expression of insulin-like growth factor I counters muscle decline in mdx mice. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;157:137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton ER. Impact of sarcoglycan complex on mechanical signal transduction in murine skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2006;290:C411–C419. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00192.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth FW. Effect of limb immobilization on skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1982;52:1113–1118. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth FW. Physiologic and biochemical effects of immobilization on muscle. Clin Orthop. 1987;219:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocca L, Pellegrino MA, Desaphy JF, Pierno S, Camerino DC, Bottinelli R. Is oxidative stress a cause or consequence of disuse muscle atrophy in mice? A proteomic approach in hindlimb-unloaded mice. Experimental physiology. 2010;95:331–350. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.050245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S, Faulkner J. Forces and powers of slow and fast skeletal muscles in mice during repeated contractions. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;436:701–710. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons DR. Role of IGF-I in skeletal muscle mass maintenance. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criswell DS, Booth FW, DeMayo F, Schwartz RJ, Gordon SE, Fiorotto ML. Overexpression of IGF-I in skeletal muscle of transgenic mice does not prevent unloading-induced atrophy. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E373–379. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.3.e373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont N, Bouchard P, Frenette J. Neutrophil-induced skeletal muscle damage: a calculated and controlled response following hindlimb unloading and reloading. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1831–1838. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90318.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont-Versteegden EE, Houle JD, Gurley CM, Peterson CA. Early changes in muscle fiber size and gene expression in response to spinal cord transection and exercise. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1124–1133. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.4.C1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans G, Haller R, Wyrick P, Parkey R, Fleckenstein J. Submaximal delayed-onset muscle soreness: correlations between MR imaging findings and clinical measures. Radiology. 1998;208:815. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.3.9722865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KJ, Jooss K, Alston J, Yang Y, Haecker SE, High K, Pathak R, Raper SE, Wilson JM. Recombinant adeno-associated virus for muscle directed gene therapy. Nature Medicine. 1997;3:306–312. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts RH, Riley DR, Widrick JJ. Physiology of a microgravity environment invited review: microgravity and skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:823–839. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.2.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florini JR, Ewton DZ, Coolican SA. Growth hormone and the insulin-like growth factor system in myogenesis. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:481–517. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-5-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley JM, Jayaraman RC, Prior BM, Pivarnik JM, Meyer RA. MR measurements of muscle damage and adaptation after eccentric exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1999;87:2311. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenette J, St-Pierre M, Cote CH, Mylona E, Pizza FX. Muscle impairment occurs rapidly and precedes inflammatory cell accumulation after mechanical loading. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R351–357. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00189.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frimel TN, Walter GA, Gibbs JD, Gaidosh GS, Vandenborne K. Noninvasive monitoring of muscle damage during reloading following limb disuse. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:605–612. doi: 10.1002/mus.20398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorza L, Sartore S, Triban C, Schiaffino S. Embryonic-like myosin heavy chains in regenerating chicken muscle* 1. Experimental Cell Research. 1983;143:395–403. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(83)90066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammers D, Adamo M, Walters T, Farrar R. Decreased induction of heat-shock proteins with age in ischemia-reperfusion injured skeletal muscle. The FASEB Journal. 2008;22:1163, 1115. [Google Scholar]

- Hill M, Goldspink G. Expression and splicing of the insulin-like growth factor gene in rodent muscle is associated with muscle satellite (stem) cell activation following local tissue damage. The Journal of Physiology. 2003;549:409. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard J, Li Y, Fu FH. Muscle injuries and repair: current trends in research. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:822–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman A, Liu M, Ye F, Walter GA, Vandenborne K. Regenerative responses in slow-and fast-twitch muscles following moderate contusion spinal cord injury and locomotor training. European journal of applied physiology. 2012:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2429-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper CE. Sarcolemmal disruption in reloaded atrophic skeletal muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1995;79:607–614. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.2.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper CE, Talbot LA, Gaines JM. Skeletal muscle damage and recovery. AACN Clin Issues. 2002;13:237–247. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200205000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C, Nystrom G, Frost R. Tissue-specific regulation of IGF-I and IGF-binding proteins in response to TNF. Growth Hormone & IGF Research. 2001;11:250–260. doi: 10.1054/ghir.2001.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch G, Cuffe S, Plant D, Gregorevic P. IGF-I treatment improves the functional properties of fast-and slow-twitch skeletal muscles from dystrophic mice. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2001;11:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKoy G, Ashley W, Mander J, Yang S, Williams N, Russell B, Goldspink G. Expression of insulin growth factor-1 splice variants and structural genes in rabbit skeletal muscle induced by stretch and stimulation. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:583. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0583v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PO, Pavlath GK. A muscle precursor cell-dependent pathway contributes to muscle growth after atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1706–1715. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.5.C1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PO, Pavlath GK. Skeletal muscle atrophy leads to loss and dysfunction of muscle precursor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1753–1762. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00292.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourkioti F, Rosenthal N. IGF-1, inflammation and stem cells: interactions during muscle regeneration. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson G, Nyberg P, Eneroth M, Ekdahl C. Performance after surgical treatment of patients with ankle fractures--14-month follow-up. Physiotherapy Research International. 2003;8:69–82. doi: 10.1002/pri.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi L, Giacinti C, Nardis C, Borsellino G, Rizzuto E, Nicoletti C, Wannenes F, Battistini L, Rosenthal N, Molinaro M, Musaro A. Local expression of IGF-1 accelerates muscle regeneration by rapidly modulating inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. FASEB J. 2007;21:1393–1402. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7690com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploutz-Snyder LL, Tesch PA, Hather BM, Dudley GA. Vulnerability to dysfunction and muscle injury after unloading. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:773–777. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottle D, Gosselin LE. Impact of mechanical load on functional recovery after muscle reloading. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:2012–2017. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M. A Pax3/Pax7-dependent population of skeletal muscle progenitor cells. Nature. 2005;435:948–953. doi: 10.1038/nature03594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley DA. Review of primary spaceflight-induced and secondary reloading-induced changes in slow antigravity muscles of rats. Adv Space Res. 1998;21:1073–1075. doi: 10.1016/s0273-1177(98)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley DA, Ellis S, Giometti CS, Hoh JF, Ilyina-Kakueva EI, Oganov VS, Slocum GR, Bain JL, Sedlak FR. Muscle sarcomere lesions and thrombosis after spaceflight and suspension unloading. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:33S–43S. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.2.S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schakman O, Gilson H, de Coninck V, Lause P, Verniers J, Havaux X, Ketelslegers JM, Thissen JP. Insulin-like growth factor-I gene transfer by electroporation prevents skeletal muscle atrophy in glucocorticoid-treated rats. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1789–1797. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schertzer J, Ryall J, Lynch G. Systemic administration of IGF-I enhances oxidative status and reduces contraction-induced injury in skeletal muscles of mdx dystrophic mice. American Journal of Physiology- Endocrinology And Metabolism. 2006;291:E499. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00101.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HK, Maxwell L, Martyn JA, Bass JJ. Nuclear DNA fragmentation and morphological alterations in adult rabbit skeletal muscle after short-term immobilization. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;302:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s004410000280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangenburg EE, Le Roith D, Ward CW, Bodine SC. A functional insulin-like growth factor receptor is not necessary for load-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Physiol. 2008;586:283–291. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.141507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Lapsley JE, Ye F, Liu M, Borst SE, Conover C, Yarasheski KE, Walter GA, Sweeney HL, Vandenborne K. Impact of viral-mediated IGF-I gene transfer on skeletal muscle following cast immobilization. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism. 2010;299:E730. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00230.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason DB, Biggs RB, Booth FW. Protein metabolism and beta-myosin heavy-chain mRNA in unweighted soleus muscle. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R300–305. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.2.R300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidball JG. Interactions between muscle and the immune system during modified musculoskeletal loading. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002:S100–109. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200210001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan K, Thompson JL, Riley DA. Sarcomere lesion damage occurs mainly in slow fibers of reloaded rat adductor longus muscles. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:1017–1023. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren GL, Hayes DA, Lowe DA, Williams JH, Armstrong RB. Eccentric contraction-induced injury in normal and hindlimb-suspended mouse soleus and EDL muscles. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:1421–1430. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.3.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witzmann F, Kim D, Fitts R. Recovery time course in contractile function of fast and slow skeletal muscle after hindlimb immobilization. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1982;52:677. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.3.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo YJ, Zhang JC, Taylor MD, Cohen JE, Hsu VM, Sweeney HL. One year transgene expression with adeno-associated virus cardiac gene transfer. Int J Cardiol. 2005;100:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F, Baligand C, Keener JE, Vohra RS, Lim W, Ruhella A, Bose P, Daniels M, Walter GA, Thompson FJ. Hindlimb muscle morphology and function in a new atrophy model combining spinal cord injury and cast immobilization. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2012 doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang G, Morrison B, Mori S, Sheikh KA. Magnetic resonance imaging of mouse skeletal muscle to measure denervation atrophy. Experimental neurology. 2008;212:448–457. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]