Abstract

Introduction

Propranolol has been shown previously to decrease the mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) after acute injury in rodent models; however, this acute injury model does not reflect the prolonged period of critical illness after severe trauma. Using our novel lung contusion/hemorrhagic shock/chronic restraint stress model, we hypothesize that daily propranolol (Prop) administration will decrease prolonged mobilization of HPC without worsening lung healing.

Methods

Male Sprague-Dawley rats underwent six days of restraint stress after undergoing lung contusion or lung contusion/hemorrhagic shock. Restraint stress consisted of a daily two hour period of restraint interrupted every 30 minutes by alarms and repositioning. Each day after the period of restraint stress, the rats received intraperitoneal propranolol (10mg/kg). On day seven, peripheral blood was analyzed for granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) via ELISA and for mobilization of HPC using c-kit and CD71 flow cytometry. The lungs were examined histologically to grade injury.

Results

Seven days after lung contusion and lung contusion/hemorrhagic shock, the addition of chronic restraint stress significantly increased the mobilization of HPC, which was associated with persistently increased levels of G-CSF and increased lung injury scores. The addition of propranolol to lung contusion/chronic restraint stress and lung contusion/hemorrhagic shock/chronic restraint stress models significantly decreased HPC mobilization and restored G-CSF levels to that of naïve animals without worsening lung injury scores.

Conclusions

Daily propranolol administration after both lung contusion and lung contusion/hemorrhagic shock subjected to chronic restraint stress decreased the prolonged mobilization of HPC from the bone marrow and decreased plasma G-CSF levels. Despite the decrease in mobilization of HPC, lung healing did not worsen. Alleviating chronic stress with propranolol may be a future therapeutic target to improve healing after severe injury.

Introduction

After severe injury, the body undergoes substantial stress which leads to physiologic changes that are accompanied by the release of healing mediators. Hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) are mediators that are released from the bone marrow in response to increased levels of norepinephrine and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) to aid in the healing of injured tissues (1, 2). At baseline, there is a homeostatic exchange of HPC between the bone marrow and the periphery which is maintained in part by stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) (2–5). After injury, a gradient of SDF-1 is created which HPC use to home to the injured tissue (6, 7). Once at the site of injury, HPC assist in healing and differentiate within the healing and healed tissues (8, 9). When the SDF-1 pathway is blocked, there is a significant decrease in the mobilization of bone marrow progenitor cells to injured tissue (10).

In a rodent model of acute injury such as lung contusion, the number of HPC in peripheral blood will return to normal a few days after injury (11, 12). This acute injury model in a rodent depicts the migration of HPC and the normal healing of injured tissue. In contrast, critically ill trauma patients do not follow this model of acute injury. Severely injured trauma patients have persistently increased serum levels of G-CSF and prolonged mobilization of HPC for weeks after injury (13–15). Severe injury and chronic stress both delay the healing of injury of injured tissue (16). The difference between animal models of acute injury and critically ill trauma patients has been hypothesized to be related to the continued exposure to stress experienced by the severely injured patients in the intensive care unit. Severely injured patients often undergo daily invasive procedures, frequent trips to the operating room, and recurrent infections. These critically ill trauma patients have a persistent hypercatecholamine state (17). In particular, norepinephrine remains dramatically increased for more than 10 days after the initial injury (17). To simulate this hypercatecholamine state, we added a further condition of chronic restraint stress (CRS) to our rodent model. Animal models of CRS worsen healing and alter various aspects of the immune system (16, 18–21). CRS results in increased levels of urine catecholamines for a duration similar to the period of critical illness after severe injury (17, 22).

Propranolol, a non-selective beta antagonist, has been studied in other states of chronic stress, such as burns; notably propranolol administration decreased the catabolism that occurs after burn injury (23). Propranolol has also been studied in other models of acute injury and decreases the release of HPC (24). Despite the involvement of HPC with healing of injured tissue, the decrease in circulating HPC after propranolol administration did not negatively impact healing (11, 25). It has been hypothesized that the propranolol mitigates the release of HPC by decreasing norepinephrine binding to beta adrenergic receptors in bone marrow but this has been only examined in the short term after acute injury (1, 11). Our study evaluated the effect of daily administration of propranolol (Prop) to rats subjected to a novel model of lung contusion, hemorrhagic shock, and chronic restraint stress on the mobilization of HPC, plasma levels of G-CSF and SDF-1, and healing of the injured lung tissue.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (5–8/group) were housed in pairs with free access to food (Teklad22/5 Rodent Diet W-8640; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and water during daily night day cycles of 12 hours each. The animals were housed and handled in accordance with IACUC regulations.

Experimental Design

The rats were allocated randomly into one of 7 groups in order to identify the effect of propranolol in mitigating the effect of chronic stress after lung contusion and lung contusion combined with hemorrhagic shock (Table 1). The groups were lung contusion (LC) alone, lung contusion followed by hemorrhagic shock (LCHS), LC with 6 days of daily restraint stress (LC/CRS), LCHS/CRS, LC/CRS with daily injection of propranolol (LC/CRS+Prop), and LCHS/CRS+Prop, and naïve animals. All groups were sacrificed on day seven after initial LC or LCHS and peripheral blood and contused lung were harvested. The naïve control animals and those not assigned to CRS underwent daily handling where food and water access was restricted for the same duration experienced by the other groups exposed to CRS.

Table 1.

| Naive | LC | LCHS | LC/CRS | LCHS/CRS | LC/CRS+Prop | LCHS/CRS+Prop | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung contusion (LC) | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hemorrhagic shock (HS) | − | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Chronic restraint stress (CRS) | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Propranolol administration (Prop) | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

LC=lung contusion; LCHS=lung contusion and hemorrhagic shock; CRS=chronic restraint stress; Prop=propranolol administration

Tissue Injury and Hemorrhagic Shock

Lung contusion was created as described previously by Baranski et al (24). In brief, after IP administration of 50 mg/kg pentobarbital, the animals were secured with their right forelimb retracted cephalad. A 10mm metal plate was attached to the right hemithorax, and lung contusion was created with a percussive nail gun (Craftsman 968514 Stapler, Sears Brands Chicago, IL). Induction of hemorrhagic shock involved removing blood until a mean arterial pressure of 30–35mmHg was achieved and maintained for 45 min. After the period of shock the animals were reinfused their shed blood.

Chronic Restraint Stress

The first period of CRS was administered the day after the animals’ injury and consisted of two hours of restraint in a cylinder which restricted their movements. Every 30 min during the 2 hours of restraint, loud, ringing, beeping, constant alarms were played for two minutes and the animals were repositioned in order to prevent habituation.

Propranolol Treatment

In the propranolol treated groups, propranolol hydrochloride, 10mg/kg (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was injected IP 10 min after the LC or LCHS and then daily for 6 days. In the groups subjected to CRS, propranolol was given immediately after the CRS.

Flow Cytometry

Peripheral blood collected on day seven after injury was used to identify HPC that were counted by flow cytometry using CD-kit and CD-71 antibodies. Briefly, whole blood was incubated with mouse anti-rat CD71 antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate and rat anti-mouse CD117 (c-Kit) antibody conjugated to phycoerythrin (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After washing and lysing the red blood cells, the samples were run on BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer equipped with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) to quantitate CD117 and CD71 positive cells.

G-CSF Measurements

G-CSF levels were determined using a sandwich ELISA (Quantikine ELISA Mouse G-CSF, R&D System, Minneapolis, MN) and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were run in duplicate. Plasma was stored at −80°C until the ELISA was run.

SDF-1 Measurements

Plasma SDF-1 levels were run in duplicate according to manufacturer’s recommendations on a commercially available, quantitative technique of sandwich enzyme immune assay (Quantikine ELISA Mouse CXCL12/SDF-1α, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The data were standardized against the protein concentrations of each sample, which was determined by taking 1μl of each sample and using the Protein A280 spectrophotometric assay (NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer, NanoDrop Technologies Inc, Wilmington, Delaware, USA).

Lung Injury Score

The lungs were harvested in formalin, and 4μm sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin were examined. The lung injury score (LIS) as described by Claridge et al. (26) was determined histologically by a blinded reader who examined the tissue for the number of inflammatory cells, the amount of interstitial edema, the amount of pulmonary edema, and alveolar integrity. The LIS ranges from 0–11.

Statistics

The data were analyzed statistically using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA) as ANOVA and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Significance was defined as *P<0.05 vs LC, **P<0.05 vs LCHS, ^P<0.05 vs LC/CRS, ^^ P<0.05 vs LCHS/CRS.

Results

The Impact of Propranolol on HPC Mobilization

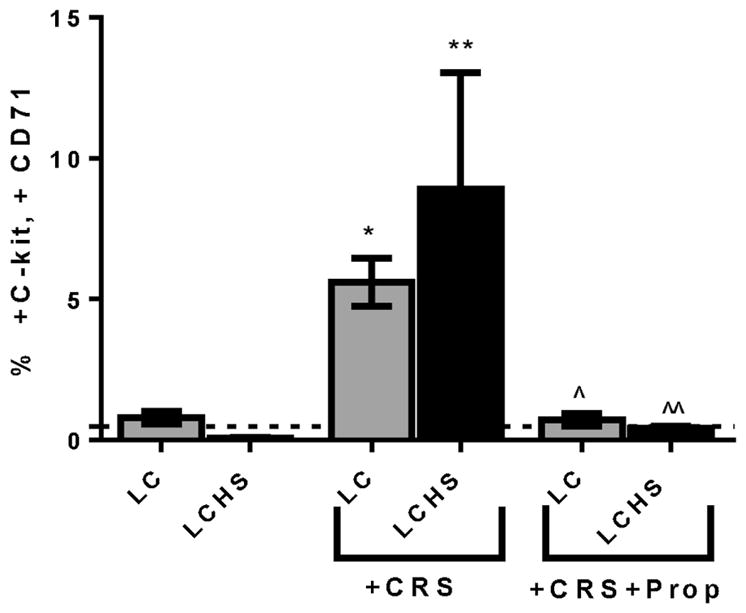

With flow cytometry, HPC that have mobilized into the peripheral blood were defined as those cells expressing both CD71 and CD117. In naïve animals, only 0.5% of cells are circulating HPC. The addition of CRS to LC and LCHS models significantly increased the mobilization of HPC (Figure 1). This observation demonstrates that the addition of CRS significantly prolonged the mobilization of HPC compared to the models of acute injury of LC and LCHS alone.

Figure 1.

Propranolol administration decreased mobilization of HPC and decreased the effect of CRS 7 days after LC and LCHS. LC=lung contusion; CRS=chronic restraint stress; LCHS=lung contusion and hemorrhagic shock; Prop=propanolol administration; *p<0.05 vs LC, **p<0.05 vs LCHS, ^p<0.05 vs LC/CRS, ^^ p<0.05 vs LCHS/CRS; N=6–9/group; dashed line represents naïve animals

When LC/CRS animals received daily propranolol after LC and CRS, the prolonged mobilization of HPC was markedly attenuated (LC/CRS+Prop: 0.7±0.2^ vs. LC/CRS: 5.6±0.9) (Figure 1). The percentage of HPC found in the peripheral blood seven days after LC/CRS+Prop was similar to that of naïve animals. Similarly, the daily administration of propranolol to LCHS/CRS animals also resulted in a significant decrease in the mobilization of HPC to the peripheral blood compared to LCHS/CRS (Figure 1).

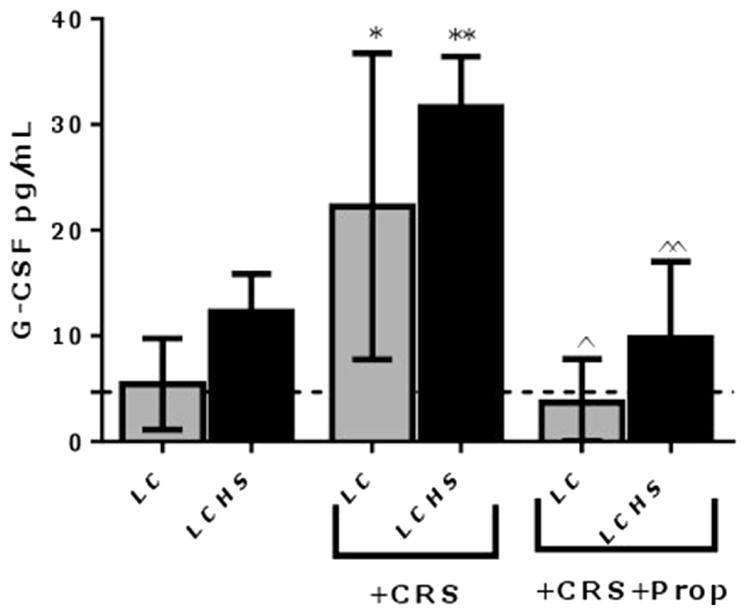

The effect of propranolol on plasma G-CSF and SDF-1 levels

Naïve animals have a plasma G-CSF level of 5±2 pg/mL. Animals subjected to CRS after lung contusion (LC/CRS) had increased plasma levels of G-CSF on day seven compared to LC animals without CRS who had normal G-CSF levels (LC/CRS: 22±15* vs. LC: 5±4 pg/mL)(Figure 2). In contrast, when the LC/CRS animals received propanolol daily, the G-CSF levels were decreased at seven days compared to LC/CRS without Prop (LC/CRS+Prop: 4±4^ vs. LC/CRS: 22±15 pg/mL). Receiving propranolol diminished the effects of CRS on G-CSF levels.

Figure 2.

The LCHS animals undergoing CRS had the greatest levels of G-CSF, 6.4 times greater than naïve and 2.6 times greater than LCHS animals (Figure 2). In comparison, the LCHS/CRS animals that received propranolol had decreased levels of G-CSF, which correlated with the findings of decreased mobilization of HPC (LCHS/CRS+Prop: 10±7^^ vs. LCHS/CRS: 32±5 pg/ml).

To begin to determine potential mechanisms involved in propranolol-mediated decreases in mobilization of HPC and G-CSF, plasma SDF-1 was measured. Seven days after injury, the plasma levels of SDF-1 after LC and LCHS alone were similar to that of naïve animals (LC: 29±3, LCHS: 20±3 vs. naïve: 22±3 pg/mg). The addition of CRS to LC and LCHS did not change plasma SDF-1 levels. The use of propranolol after LC/CRS and LCHS/CRS did not alter plasma SDF-1 levels (LC/CRS: 25±3 vs. LC/CRS+Prop: 26±5 and LCHS/CRS: 22±5 vs. LCHS/CRS+Prop: 22±3 pg/mg). Plasma SDF-1 levels on day seven did not significantly change in any of the rodent models.

The impact of propranolol use on healing of injured tissue

Because the administration of propranolol decreased the plasma levels of G-CSF and decreased the mobilization of HPC, one might hypothesize that decreased mobilization of HPC would decrease the healing of injured lung tissue. We found that seven days after LC alone there was a normal lung injury score (LC: 0.8±0.4 vs. naïve: 1.0±0.5)(Table 2). Those animals undergoing LCHS alone had a lung injury score of 3.7±0.8 on day seven. These findings are consistent with previously published data (11, 25). Exposure to CRS worsened the lung injury score at seven days compared to those animals undergoing LC and the LCHS alone (Table 2). When further examining the components of the LIS, the number of inflammatory cells significantly increased with the addition of CRS to LC and LCHS models (Table 2). CRS did not significantly alter the amount of interstitial edema, intra-alveolar edema, or alveolar integrity.

Table 2.

| Naive | LC | LCHS | LC/CRS | LCHS/CRS | LC/CRS+Prop | LCHS/CRS+Prop | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Injury Score | 1.0±0.5 | 0.8±0.4 | 3.7±0.8 | 4.8±2.6* | 7.2±2.2** | 3.8±2.8 | 5.2±1.3 |

| Inflammatory cells/ hpf | 0.3±0.1 | 0±0 | 0.4±0.5 | 1.9±0.7* | 2.2±0.8** | 1.5±0.8 | 1.5±0.6 |

| Interstitial Edema Score | 0±0 | 0.8±0.5 | 2±0 | 1.4±0.5 | 2.3±0.5 | 1.5±1.1 | 1.8±0.8 |

| Intra-alveolar Edema Score | 0.7±0.5 | 0±0 | 1±0.7 | 0.4±0.5 | 1.3±0.5 | 0.7±0.5 | 0.5±0.1 |

| Alveolar Integrity Score | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0.4±0.5 | 0.7±0.8 | 1.3±0.5 | 0.6±0.5 | 1.2±0.4 |

LC=lung contusion; LCHS=lung contusion and hemorrhagic shock; CRS=chronic restraint stress; Prop=propranolol administration; Data presented as mean±SD.

P<0.05 vs. LC and

P<0.05 vs. LCHS

The administration of propranolol to LC/CRS animals did not significantly worsen the LIS compared to the LC/CRS group (LC/CRS+Prop: 3.8±2.8 vs. LC/CRS: 4.8±2.6) (Table 2). Similarly, the LCHS/CRS animals receiving propranolol had an LIS similar to LCHS/CRS (LCHS/CRS+Prop: 5.2±1.3 vs. LCHS/CRS: 7.2±2.2). There were no significant differences in the amount of inflammatory cells, interstitial edema, intra-alveolar edema, or alveolar integrity in the groups that received propranolol as compared to those that did not.

Discussion

The trafficking of HPC from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood and eventually to injured tissue is believed to be beneficial and aids in the host defense and is integral to wound healing (9, 27). However, severe traumatic Injury and shock are associated with significant increases in norepinephrine levels and subsequently increased mobilization of HPC (15, 17). Previously, propranolol administration in acute injury rodent models has been shown to mitigate the release of HPC from the bone marrow (11, 24). This is the first study to demonstrate that chronic restraint stress significantly prolongs the mobilization of HPC and that this effect of CRS following LC and LCHS can be abrogated with daily propranolol use.

Following injury, HPC mobilize from the bone marrow and home to the injured area to assist in healing (9, 27). The number of HPC in peripheral blood returned to naïve levels following acute injury, as seen with the LC animals (11, 25). However, the addition of CRS prolonged the mobilization of HPC. Seven days post injury the percentage of HPC in the peripheral blood remained significantly elevated following both LC/CRS and LCHS/CRS. The more severe injury model of LCHS/CRS has the greatest elevation of HPC compared to the other models suggesting that both severity of injury and degree of stress impacts the degree of mobilization of HPC.

Administering propranolol after LC/CRS significantly decreased the percentage of HPC found in the peripheral blood. The percentage of HPC found in the peripheral blood seven days after LC/CRS+Prop was similar to that of naïve animals. When LC/CRS and LCHS/CRS animals received daily propranolol, the prolonged mobilization of HPC was markedly attenuated and abrogated the effects of CRS.

Katayama et al. (1) demonstrated a critical link between the sympathetic nervous system, particularly norepinephrine, and G-CSF induced mobilization of HPC. G-CSF is released early in the pathway of the mobilization of HPC from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood. Plasma G-CSF levels were shown to be significantly elevated at three and 24 hours following LC and LCHS (24). In this study, CRS prolonged the increase in plasma G-CSF levels seven days following LC and LCHS models. The finding of persistent plasma G-CSF elevation with the addition of CRS correlated with the finding of prolonged mobilization of HPC in both LC and LCHS models. The induction of the mobilization of HPC both in non-injured rats and humans via G-CSF injection has been shown to be both time and dose dependent resulting in peripheral blood levels of HPC peaking up to 100-fold above baseline at 3–6 days after G-CSF administration (28, 29). Our study demonstrated a similar, prolonged increase in circulating HPC following LC/CRS and LCHS/CRS. Plasma G-CSF levels had the greatest increase after LCHS/CRS. Plasma G-CSF levels are increased during physiological stress in pediatric burn patients and following endurance and short-duration exercise (30, 31). In ICU patients, plasma G-CSF levels 24 hours after admission appeared to be predictive of worsening organ dysfunction and early mortality in severe sepsis (32). Plasma G-CSF levels are also a marker of ongoing mobilization of HPC to peripheral blood in severely injured trauma patients (13). Patients who presented in shock with a systolic blood pressure less than 90mmHg had a more profound and sustained elevation of plasma G-CSF compared to normotensive patients (13).

When the LC/CRS and LCHS/CRS animals received propanolol daily, the G-CSF levels were significantly decreased at seven days. The findings of this animal study correlated with decreased mobilization of HPC in the peripheral blood of severely injured trauma patients who were randomized to receive propranolol (15). The significant association between propranolol administration, endogenous plasma G-CSF levels, and mobilization of HPC into the peripheral blood could be a potential therapeutic option for bone marrow protection following severe traumatic injury and shock.

Lévesque et al. (28) had shown that during the mobilization of HPC there is a concomitant decrease in SDF-1 levels within the bone marrow. This current study demonstrated that seven days following LC/CRS and LCHS/CRS, plasma levels of SDF-1 are not elevated. Thus, the CRS increases in the mobilization of HPCs were not mediated by changes in plasma SDF-1 levels. Tissue SDF-1 levels are elevated after ischemic cardiomyopathy and as the tissue healed, SDF-1 levels decreased (33). One explanation of our findings that there was no change in plasma SDF-1 levels following CRS despite increased mobilization of HPC may be that SDF-1 should be measured in the bone marrow and at the site of injury.

HPC are integral to healing of injured tissue (9, 27). HPC have been found within healing lungs as well as skin (34, 35). In addition, beta adrenergic receptors are found widely in fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, as well as HPC (36–38). In particular, the mobilization of HPC was shown to be mediated through beta 2 and 3 adrenergic receptors (38, 39). In this study, the use of propranolol, a non-selective beta antagonist, decreased plasma G-CSF levels and the mobilization of HPC and it was hypothesized that reduced mobilization of HPC could worsen the healing of injured lung tissue. This study demonstrated that propranolol use did not worsen healing of injured lung tissue. Animals that received propranolol had lung injury scores similar to CRS animals that did not receive propranolol. This implied that a reduction in prolonged mobilization of HPC did not negatively impact healing. This study also demonstrated that CRS following LC and LCHS did worsen healing of injured lung tissue. These findings are supported by Romana-Souza et al. (40) who demonstrated that after major burn injuries there was a systemic release of catecholamines that induced a stress state associated with delayed burn wound healing. Similarly, high dose propranolol (25 mg/kg) was shown to block the deleterious effects of circulating catecholamines and improved cutaneous wound healing in burned chronically stressed mice (40). However, when propranolol dosing was increased to 50 mg/kg in rats Raut et al. (41) showed that the beneficial effects of propranolol administration were lost and there was both decreased reepithelialization and collagen density. Further study demonstrating the importance of propranolol dosing in wound healing was done by Zhang et al. (42) who demonstrated that propranolol infusion at 1 mg/kg/hr in rabbits (significantly less than the 50 mg/kg doses in rabbits) did not negatively impact wound reepithelialization. Clinically most relevant, in adult burn patients that received an average of 3 mg/kg/day of propranolol there was an associated improvement in donor site healing time (36).

A dramatic increase in circulating catecholamines immediately after severe trauma and hemorrhagic shock is fundamentally protective; however, there is a point when persistent catecholamine elevation becomes deleterious. Adverse effects of adrenergic stress in critical illness include impaired diastolic function, tachycardia, pulmonary edema, inhibition of peristalsis, hyperglycemia, and catabolism (43). Therapeutic options to decrease adrenergic stress include temperature control, analgesia, and reduction of heart rate with beta adrenergic antagonists (43). In the most clinically relevant model of LCHS/CRS, animals subjected to lung contusion and hemorrhagic shock and daily CRS, have persistently elevated G-CSF levels, prolonged mobilization of HPC, and worsened lung healing. When propranolol is given after LC/CRS or LCHS/CRS the levels of HPC and G-CSF in the peripheral blood are decreased. The animals that received propranolol have similar healing to the animals that did not receive propranolol. Further study is needed to determine if reducing chronic stress following severe injury may improve bone marrow dysfunction and if alteration of propranolol dosing can improve the healing of injured tissue.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 NIH GM105893-01A1 and T32 GM069330.

Footnotes

Presented at the 10th Annual Academic Surgical Congress in Las Vegas, NV on February 3, 2015.

The authors have nothing to disclose nor have any conflicts to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Katayama Y, Battista M, Kao W, Hidalgo A, Peired AJ, Thomas SA, Frenette PS. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egres from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, Lahav M, Peled A, Habler L, et al. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez P, Carrillo E, Vélez C, Hita-Contreras F, Martínez-Amat A, Rodríguez-Serrano F, et al. Regulatory systems in bone marrow for hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells mobilization and homing. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:312656. doi: 10.1155/2013/312656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonig H, Papyannopoulou T. Mobilization of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells: general principles and molecular mechanisms. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;904:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-943-3_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massberg S, von Andrian UH. Novel trafficking routes for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1179:87–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashimoto N, Jin H, Liu T, Chensue S, Phan S. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;13:243–252. doi: 10.1172/JCI18847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Mora A, Shim H, Stecenko A, Brigham KL, Rojas M. Role of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in the pathogenesis of lung injury and fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:291–299. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0187OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badiavas E, Abedi M, Butmarc, Falanga V, Quesenberry P. Participation of bone marrow derived cells in cutaneous wound healing. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:245–250. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah S, Ulm J, Sifri ZC, Mohr AM, Livingston DH. Mobilization of bone marrow cells to the site of injury is necessary for wound healing. J Trauma. 2009;67:315–321. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a5c9c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X, Zhu F, Zhang M, Zeng D, Luo D, Liu G, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 enhances wound healing through recruiting bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to the wound area and promoting neovascularization. Cells Tissues Organs. 2013;197:103–113. doi: 10.1159/000342921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasupuleti LV, Cook KM, Sifri ZC, Alzate WD, Livingston DH, Mohr AM. Do all β-blockers attenuate the excess hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization from the bone marrow following trauma hemorrhagic shock? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:970–975. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beiermeister KA, Keck BM, Sifri ZC, Elhassan IO, Hannoush EJ, Alzate WD, et al. Hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization is mediated through beta-2 and beta3 receptors after injury. J Trauma. 2010;69:338–343. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e5d35e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook KM, Sifri ZC, Baranski GM, Mohr AM, Livingston DH. The role of plasma granulocyte colony stimulating factor and bone marrow dysfunction after severe trauma. J Am CollSurg. 2013;216:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livingston DH, Anjaria D, Wu J, Hauser CJ, Chang V, Deitch EA, Rameshwar P. Bone marrow failure following severe injury in humans. Ann Surg. 2003;238:748–753. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094441.38807.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bible LE, Pasupuleti LV, Alzate WD, Gore AV, Song KJ, Sifri ZC, Livingston DH, Mohr Early propranolol administration to severely injured patients can improve bone marrow dysfunction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:54–60. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gouin JP, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The impact of psychological stress on wound healing: methods and mechanisms. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2011;31:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woolf PD, McDonald JV, Feliciano DV, Kelly MM, Nichols D, Cox C. The catecholamine response to multisystem trauma. Arch Surg. 1992;127:899–903. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420080033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan SG, Shao L, Ding GF. A suppressive protein generated in peripheral lymph tissue induced by restraint stress. Advances in Neuroimmunology. 1996;6:279–288. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(96)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padgett D, Marucha P, Sheridan J. Restraint Stress Slows Cutaneous Wound Healing in Mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1998;12:64–73. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris RB, Mitchell TD, Simpson J, Redmann SM, Youngblood BD, Ryan DH. Weight loss in rats exposed to repeated acute restraint stress is independent of energy or leptin status. Am J Physiol Regulatory Integrative Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R77–R88. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2002.282.1.R77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voorhees JL, Tarr AJ, Wohleb ES, Godbout JP, Mo X, Sheridan JF, et al. Prolonged restraint stress increases IL-6, reduces IL-10, and causes persistent depressive-like behavior that is reversed by recombinant IL-10. PLOS one. 2013;8:e58488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vargovic P, Ukropec J, Laukova M, Kurdiova T, Balaz M, Manz B, et al. Repeated immobilization stress induces catecholamine production in rat mesenteric adipocytes. Stress. 2013;16:340–352. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2012.736046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herndon DN, Hart DW, Wolf SE, Chinkes DL, Wolfe RR. Reversal of catabolism by beta-blockade after severe burns. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1223–1229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baranski GM, Offin MD, Sifri ZC, Elhassan IO, Hannoush EJ, Alzate WD, et al. Beta-blockade protection of bone marrow following trauma: the role of G-CSF. J Surg Res. 2011;170:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohr AM, Elhassan IO, Hannoush EJ, Sifri ZC, Offin MD, Alzate WD, et al. Does beta blockade post injury prevent bone marrow suppression? J Trauma. 2011;70:1043–1050. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182169326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claridge JA, Enelow RI, Young JS. Hemorrhage and resuscitation induce delayed inflammation and pulmonary dysfunction in rats. J Surg Res. 2000;92:206–213. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badami CD, Livingston DH, Sifri ZC, Caputo FJ, Bonilla L, Mohr AM, Deitch EA. Hematopoietic progenitor cells mobilize to the site of injury after trauma and hemorrhagic shock in rats. J Trauma. 2007;63:596–600. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318142d231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levesque JP, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Williams B, Winkler IG, Simmons PJ. Mobilization by either cyclophosphamide or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor transforms the bone marrow into a highly proteolytic environment. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:440–449. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00788-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato N, Sawada K, Takahashi TA, Mogi Y, Asano S, Koike T, Sekiguchi S. A time course study for optimal harvest of peripheral blood progenitor cells by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in healthy volunteers. Exp Hematol. 1994;22:973–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mikhal’chik EV, Piterskaya JA, Budkevich LY, Pen’kov LY, Facchiano A, DeLuca C, et al. Comparative study of cytokine content in the plasma and wound exudate from children with severe burns. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2009;148:771–775. doi: 10.1007/s10517-010-0813-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki K, Nakaji S, Yamada M, Totsuka M, Sato K, Sugawara K. Systemic inflammatory response to exhaustive excercise. Cytokine kinetics Exerc Immunol Rev. 2002;8:6–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bozza FA, Salluh JI, Japiassu AM, Soares M, Assis EF, Gomes RN, et al. Cytokine profiles as markers of disease severity in sepsis: a multiplex analysis. Crit Care. 2007;11:R49. doi: 10.1186/cc5783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Askari AT, Unzek S, Popovic ZB, Goldman CK, Forudi F, Kiedrowski M, et al. Effect of stromal-cell-derived factor 1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. The Lancet. 2003;362:697–703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badiavas E, Abedi M, Butmarc, Falanga V, Quesenberry P. Participation of Bone Marrow Derived Cells in Cutaneous Wound Healing. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:245–250. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hannoush EJ, Sifri ZC, Elhassan IO, Mohr AM, Alzate WD, Offin M, Livingston DH. Impact of enhanced mobilization of bone marrow derived cells to site of injury. J Trauma. 2011;71:283–291. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318222f380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali A, Herndon DN, Mamachen A, Hasan S, Andersen CR, Grograns R, et al. Propranolol attenuates hemorrhage and accelerates wound healing in severely burned adults. Crit Care. 2015;19:217. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0913-x. epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saba F, Soleimani M, Kaviani S, Abroun S, Sayyadipoor F, Behrouz S, Saki N. G-CSF induces up-regulation of CXCR4 expressionin human hematopoietic stem cells by beta-adrenergic agonist. Hematology. 2014 Dec 17; doi: 10.1179/1607845414Y.0000000220. epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasupuleti LV, Cook KM, Sifri ZC, Kotamarti S, Calderon GM, Alzate WD, et al. Does selective beta-1 blockade provide bone marrow protection after trauma/hemorrhagic shock? Surgery. 2012;152:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiegel A, Shivtiel S, Kalinkovich A, Luden A, Netzer N, Goichberg P, et al. Catecholaminergic neurotransmitters regulate migration and repopulation of immature human CD34? cells through Wnt signaling. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1123–1131. doi: 10.1038/ni1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romana-Souza B, Porto LC, Monte-Alto-Costa A. Cutaneous wound healing of chronically stressed mice is improved through catecholamine blockade. Exp Derm. 2010;19:821–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raut SB, Nerlekar SR, Pawar S, Patil AN. An evaluation of the effects of nonselective and cardioselective β-blockers on wound healing in Sprague Dawley rats. Ind J Pharm. 2012;44:629–633. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.100399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang XJ, Meng C, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, Aarsland A, Jeschke MG, Herndon DN. Acute propranolol infusion stimulates protein synthesis in rabbit skin wound. Surgery. 2009;145:558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunser MW, Hasibeder WR. Sympathetic overstimulation during critical illness: adverse effects of adrenergic stress. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24:293–316. doi: 10.1177/0885066609340519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]