Abstract

Childhood externalizing problems are more likely to be severe and persistent when combined with high levels of callous-unemotional (CU) behavior. A handful of recent studies have shown that CU behavior can also be reliably measured in the early preschool years, which may help to identify young children who are less likely to desist from early externalizing behaviors. The current study extends previous literature by examining the role of CU behavior in very early childhood in the prediction of externalizing problems in both middle and late childhood, and tests whether other relevant child characteristics, including Theory-of-Mind (ToM) and fearful/inhibited temperament moderate these pathways. Multi-method data, including parent reports of child CU behavior and fearful/inhibited temperament, observations of ToM, and teacher-reported externalizing problems were drawn from a prospective, longitudinal study of children assessed at ages 3, 6, and 10 (N=241; 48% female). Results demonstrated that high levels of CU behavior predicted externalizing problems at ages 6 and 10 over and above the effect of earlier externalizing problems at age 3, but that these main effects were qualified by two interactions. High CU behavior was related to higher levels of externalizing problems specifically for children with low ToM and a low fearful/inhibited temperament. The results show that a multitude of child characteristics likely interact across development to increase or buffer risk for child externalizing problems. These findings can inform the development of targeted early prevention and intervention for children with high CU behavior.

Keywords: callous-unemotional behavior, externalizing problems, theory-of-mind, fearful/inhibited temperament

Across the preschool years, children show dramatic increases in their ability to regulate behavior (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000), internalize social norms (Kochanska & Aksan, 2006), and develop an awareness of others’ desires, beliefs, and emotions (Wellman, 2014). By the end of the preschool period, these core developmental milestones help to reduce the normative high levels of aggressive behaviors that are typically shown by children from ages two to four years old (Hay, Payne, & Chadwick, 2004; Tremblay, 2000). However, some children show persisting externalizing problems and do not reduce their aggressive behaviors across the transition from the preschool period to the middle- and late-childhood period (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004). These children have been shown to have a wide range of adjustment problems in both social and academic domains across the school-age years (Caspi & Moffitt, 1995; Dodge, Greenberg, & Malone, 2008; Morrow, Hubbard, McAuliffe, Rubin, & Dearing, 2006). Thus, research has focused on identifying specific developmental and child-level characteristics that predict persisting forms of aggressive and externalizing behavior problems into the early school period (Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003) in order to more effectively target children at highest risk of poor outcomes via intervention or treatment (i.e., those who are less likely to desist from normatively high initial levels of aggression). The current study examines high callous-unemotional behavior, poor theory-of-mind, and low fearful/inhibited temperament as potential child-level contributors to the development of externalizing problems across childhood.

Callous-Unemotional (CU) Behavior

One approach that has been adopted in recent years to identify those children at highest risk of persisting externalizing problems has focused on the presence or absence of callous unemotional (CU) behavior (see Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, 2014 for a review). Children with high levels of CU behavior tend to prefer dangerous and novel activities (Frick et al., 2003), exhibit hyporesponsivity to affective cues (Blair, 1999; Kimonis et al., 2006), and low levels of empathy and guilt (Frick & White, 2008). These characteristics appear to increase the risk of children developing particularly severe and chronic externalizing problems over time (Frick et al., 2014). A growing body of studies suggests that childhood CU behavior adds predictive utility in forecasting the severity of later externalizing behavior, particularly in the late childhood and adolescence period, over and above stability in externalizing behavior in general (Frick et al., 2003). Moreover, these findings have been replicated across different types of samples (e.g., community, clinical, forensic), and different demographic backgrounds (e.g., age, gender, and culture; Frick et al., 2014).

Preschool CU Behavior and Later Externalizing Problems

More recently, studies have begun to examine CU behavior in preschool samples, as increasing evidence demonstrates that CU behavior can be reliably measured as early as at age three (Hyde, Shaw, Gardner, Cheong, Dishion, & Wilson, 2013; Kimonis et al., 2006; Willoughby, Waschbusch, Moore, & Propper, 2011). Consistent with research findings with older children and adolescents, CU behavior in the preschool years is also associated with severe and persisting externalizing problems across childhood. For example, Willoughby, Mills-Koonce, Gottfredson, and Wagner (2014) found that high CU behavior at age three uniquely predicted high and stable teacher-rated aggression from ages six to 12. In the current sample, Waller, Hyde, Grabell, Alves, and Olson (2015) showed that higher CU behavior (mother-reported) at age three predicted teacher-reported externalizing problems concurrently and longitudinally at age six while controlling for earlier ADHD and oppositional behaviors. Taken together, these studies highlight that early CU behavior may represent an important way to identify young children at high risk of severe and persisting externalizing problems across childhood (Hyde et al., 2013; Waller et al., 2015).

While there appears to be a link between early CU behavior and severe externalizing problems, however, questions continue to surround the developmental processes by which CU behavior affects externalizing outcomes and how those processes are moderated by other child level factors. A handful of recent studies has pointed to the importance of examining other child features, such as fearlessness or behavioral inhibition, along with CU behavior in order to understand the heterogeneity in developmental pathways to conduct problems (Fanti, Panayiotou, Lazarou, Michael, & Georgiou, 2015; Kingzell, Fanti, Colins, Frogner, Andershed, & Andershed, 2015). Broadly, theory and some empirical evidence suggest that disruptions in affective development may play a role in the development of severe antisocial problems in high-CU children (Frick & Viding, 2009). The theoretical premise is that insensitivity to emotional cues in others (e.g., upset parent signaling punishment, crying peer signaling distress) and a fearless or bold temperament may interfere with the development of empathy and guilt (Fowles & Kochanska, 2000). Jointly, both affective and cognitive deficits could increase the risk for severe externalizing problems when combined with high levels of CU behavior. In particular, when children are poorly attuned to others and experience fearless and low shy temperaments on top of their high CU characteristics, they may be more likely to show reduced conscience (Dadds & Salmon, 2003) and higher aggressive behavior (Blair, 1995) across development. Because research on CU behavior among preschoolers is only emerging, not many studies have yet examined the interaction of CU behavior with other cognitive or temperamental characteristics that also predict persisting externalizing problems. The current study thus examined whether links between CU behavior and later externalizing problems were moderated by children’s cognitive capabilities related to recognizing or knowing others’ perspective, as indexed by Theory-of-Mind (ToM) and their affective propensity towards distress or feeling, as indexed by fearful/inhibited temperament.

Theory-of-Mind (ToM)

During the preschool period, children show a dramatic development in ToM, defined as the ability to understand that others can have desires, beliefs, and emotions that are different from your own, and that mental states influence behavior (Wellman, 2014). Although most children show ToM understanding via successful performance on false-belief tasks by the end of preschool years, there are individual differences in the rate of development of ToM (Wellman, Harris, Banerjee, & Sinclair, 1995; Wellman, Cross, & Watson, 2001). Evidence from longitudinal research suggests that the consequences of a slower rate of ToM development in real-world social behavior endure long after children have developed ToM (Astington, 2001). For example, a number of studies have demonstrated that delays in ToM are related to higher externalizing behavior during childhood (e.g., Hughes, Dunn, & White, 1998; Hughes & Ensor, 2006; Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000). This may be because poor ToM contributes to biases and difficulties in interpreting social cues, which can result in reactive and aggressive behaviors toward others (Dodge & Coie, 1987). For example, in the current sample, Choe, Lane, Grabell, and Olson (2013) found that preschoolers who had low levels of ToM showed more hostile attribution biases at age six.

Whereas these studies reported that low ToM is related to more externalizing behavior, this finding has not been consistently replicated across all studies. For instance, no significant link between ToM and aggression was reported in both a cross-sectional (e.g., Hughes, White, Sharpen, & Dunn, 2000), and a longitudinal study (Olson, Lopez-Duran, Lunkenheimer, Chang, & Sameroff, 2011). This inconsistency across findings of previous studies suggests that preschool-aged low levels of ToM alone may not be sufficient to explain increased risk for more externalizing problems (Hughes, 2011). In fact, Wellman (2014) argued that competence in ToM understanding does not always translate into competence in social behaviors (e.g., prosocial behavior), and in the same vein, Astington (2003) wrote ToM is “sometimes necessary but never sufficient (p. 13)” to guide children’s social interactions. In other words, low ToM may not independently contribute to later externalizing problems, but could operate to increase risk for later externalizing in conjunction with other child-level characteristics.

In the current study, we examined how individual differences in ToM contribute to the development of externalizing problems conjointly with high CU behavior. As outlined, children with low levels of ToM are thought to be at increased risk for externalizing problems due to difficulties in understanding others’ intention and poor cognitive empathy (Hughes, 2011). At the same time, children with high CU behavior are thought to be at risk for externalizing problems because of deficits in affective empathy (Waller, Hyde, Grabell, Alves, & Olson, 2015), which seems to underlie difficulties associating their harmful actions toward others with emotions of distress in others (Blair, 1995). Together, it is plausible that children who have dual risk—lower ToM and higher CU behavior—could show worse externalizing outcomes when compared to children who have low levels of ToM or high levels of CU behavior alone. In other words, high CU children who have high levels of ToM may show less severe externalizing problems compared to those who have low levels of ToM (i.e., protective effect of high ToM). It is noteworthy that previous studies that have examined CU behavior and ToM (i.e., cognitive empathy) have typically assessed older samples of children or adolescents and have focused on how these CU behavior and ToM are related to each other (Dadds et al., 2009; Jones, Happé, Gilbert, Burnett, & Viding, 2010). Also, recent studies have begun to investigate the extent of cognitive versus affective empathic deficits in CU behavior versus symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), suggesting that low affective empathy may be unique to CU behavior whereas cognitive empathy may be more unique to ASD symptoms although some evidence suggests that it is shared by both ASD symptoms and CU behavior (e.g., O’Nions, Sebastian, McCrory, Chankiluke, Happé, & Viding, 2014; Pasalich, Dadds, & Hawes, 2014). In the current sample, Waller et al. (2015) previously reported mother-reported CU behavior was negatively correlated with ToM concurrently at age three, although this association became non-significant when overlap between ADHD, oppositional, and CU behavior was accounted for. However, we have yet to test whether CU behavior and ToM interact with one another to predict more severe externalizing problems in middle and late childhood.

Fearful/Inhibited Temperament

A second child characteristic that is thought to be important to the development of externalizing behavior, particularly CU behavior, is a low fearful or inhibited temperament. A large body of literature suggests that optimal levels of fear and shyness (i.e., an optimal normative level of temperamental anxiety) are conducive to the development of conscience (Kochanska, Gross, Lin, & Nichols, 2002) and the inhibition of aggression (Frick & Viding, 2009) due to the discomfort felt after wrongdoing and the modulatory effect of fear on disinhibition associated with externalizing behavior. Thus, normative levels of arousal and anxiety, which could be assessed with temperament measures such as fear and shyness (i.e., behavioral inhibition), could inhibit future aggressive or rule-breaking behavior (Lahey & Waldman, 2003; Patrick, Fowles, & Krueger, 2009). Importantly, high levels of CU behavior have been linked to low anxiety in studies assessing the late-childhood period (e.g., Pardini, Lochman, & Powell, 2007; Waller, Wright, et al., 2015) although other studies have reported that high levels of CU behavior are related to higher levels of internalizing problems of anxiety (e.g., Berg et al., 2013; Essau, Sasagawa, & Frick, 2006). To address this heterogeneity, Kimonis and colleagues have proposed differentiating between primary versus secondary variants within children who show high CU behavior (see Kimonis, Frick, Cauffman, Goldweber, & Skeem, 2012; Kimonis, Skeem, Cauffman, & Dmitrieva, 2011). In particular, the primary CU behavior variant is theorized to be defined by low levels of emotional arousal whereas the secondary variant is associated with high levels of emotional sensitivity and anxiety. Importantly, both variants are theorized to show comparable levels of disruptive behavior problems but via different emotional mechanisms; deficits in processing emotional stimuli for the primary variant and emotion dysregulation for the secondary variant (Kimonis et al., 2012). Despite work examining associations between CU behavior and emotional sensitivity and the person-centered approach of describing primary versus secondary variants, few studies have examined main and interactive effects of CU behavior and emotional sensitivity in the prediction of externalizing problems. In particular, it is yet to be established the extent to which high levels of CU behavior versus low levels of temperamental fear and behavioral inhibition (i.e., shyness) in early childhood are related to more externalizing behavior later on, or again whether there is some effect of dual risk whereby low levels of fearful/inhibited temperament combined with high levels of CU behavior may be particularly problematic leading to increasing externalizing problems across childhood.

Gaps in the Literature

Several gaps characterize this emerging literature that has, to date, linked early childhood CU behavior to greater risk for persisting and chronic externalizing problems across childhood. First, studies are needed that examine long-term developmental consequences of early CU behavior across even longer-follow-up periods. In the current sample, Waller et al. (2015) have previously reported that CU behavior at age three predicted externalizing problems at the transition to school at age six. However, we have yet to establish whether CU behavior at age three continues to predict externalizing problems at the end of elementary school at age 10. Given that important developmental changes occur during middle childhood (ages five to 10), which likely have long-term implications for persisting externalizing problems across adolescence and into adulthood (Feinstein & Bynner, 2006), an examination of whether early childhood CU behavior separately predicts externalizing problems at both ages six and 10 is needed to isolate developmental specificity in the extent of any predictive associations. Second, poor ToM and high CU behavior in the early preschool period have yet to be considered together in terms of how they individually influence or interact to predict the development of more externalizing problems in late childhood. In particular, it is not known whether cognitive components of empathy (e.g., ToM) could buffer or exacerbate the development of more severe externalizing behavior in relation to the key emotional deficits in children with high levels of CU behavior (e.g., low affective empathy; Waller et al., 2015). Finally, we need a clearer understanding of whether early childhood fearful/inhibited temperament interacts with CU behavior to predict later adjustment, which may shed light on different emotional processes involved in the development of externalizing problems.

Current Study

The overarching goal of this study was to examine the unique contributions of early CU behavior, ToM, and fearful/inhibited temperament at age three to school-aged teacher-reported externalizing problems assessed at ages six and 10, over and above the effects of earlier externalizing problems and relevant covariates. We hypothesized that higher levels of CU behavior, lower ToM, and lower fearful/inhibited temperament at age three would each uniquely predict more externalizing problems in middle (age six) and late (age 10) childhood. Our second goal was to explore interactions between early childhood CU behavior, ToM, and fearful/inhibited temperament. We hypothesized that high levels of early CU behavior would predict externalizing problems at ages six and 10 more strongly when ToM or fearful/inhibited temperament were low, and less strongly when ToM or fearful/inhibited temperament were high. Examining the joint contributions of these factors has the potential to inform early identifications of multiple developmental pathways of children with high CU behavior, illustrating the developmental multifinality of early CU behavior based on levels of emotional characteristics, with key translational implications.

Method

Participants

Participants were 241 children (118 girls) who were part of a longitudinal study of young children at risk for school-aged conduct problems (Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005). Families were recruited through preschools, advertisements in newspapers, and pediatrician referrals. Once parents indicated interest in participating in the study, a screening questionnaire and a short telephone interview were conducted to explain the longitudinal study procedure and to determine the eligibility of the family. Children with serious health problems, mental retardation, and pervasive developmental disorders were excluded. Participating children represented the full range of externalizing problems severity on the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 2–3 (CBCL 2/3; Achenbach, 1992), and children who were in the upper range of the externalizing problem subscale of the CBCL were oversampled for the purpose of the project.

The study consisted of three time points: children were around three years old at T1 (M = 41.40, SD = 2.09 months), six years old at T2 (M = 68.90, SD = 3.85 months), and 10 years old at T3 (M = 125.52, SD = 7.20 months). Families consisted of primarily those self-identifying as European American (85%), as well as 5% self-identifying as African American, 8% biracial, and 2% other racial-ethnic groups. The majority of mothers (81%) and fathers (76%) had completed four years of college and above (e.g., graduate or professional training) and the rest (19% of mothers and 24% of fathers) had achieved high school education. The median family income was $52,000 with the range of $20,000–$100,000. Most mothers were married (89%), 5% were single, 3% lived with a partner, and 3% were divorced.

At T1, mothers and a subsample of fathers (66%) answered questionnaires about demographic information and child behavior. To test whether participants for whom paternal data were available differed from the participants with mother participation only, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to compare major study variables across the two groups. There were no significant differences between the two subsamples (Kerr, Lopez, Olson, & Sameroff, 2004). Among the total sample, 91% of families continued to participate in the study at T3. Families who left the study did not differ on socio-demographic characteristics except that they reported a lower average annual household income than families who remained in the study, t(20) = 2.09, p < .05. Household income was thus included as a covariate in all analyses. Missing data was handled using multiple imputation (Little & Rubin, 2002) in SPSS vs. 22, which creates five imputed data sets. Simulation studies have shown that multiple imputation results in unbiased estimates while preserving sample size and statistical power (Asendorpf, van de Schoot, Denissen, & Hutteman, 2014; covariance coverage: mother-reported data = .97–.98; father-reported data = .62–.65; teacher-reported data = .78–.80; observed data = .93).

Procedures

This study was approved by the Behavioral Sciences IRB at the University of Michigan. Written consent was obtained from parents and teachers and verbal assent was obtained from the children. At T1, children were observed and interviewed during a four-hour Saturday laboratory session at a local preschool while completing a series of cognitive and self-regulatory tasks (Olson et al., 2005). Mothers and fathers completed questionnaires assessing children’s behavioral adjustment and temperament in their homes, and were given $100 for participation. At all three time points, children’s teachers were asked to provide ratings of child externalizing behavior at school. Approximately 80% of teachers at T1, 83% of teachers at T2, and 83% of teachers at T3 completed questionnaires. Teachers were given gift certificates for participating.

Measures

CU behavior (parent-report)

Mothers and fathers completed the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 2–3 (CBCL/2-3, Achenbach, 1992) at T1. The CBCL is a 99-item measure, which is widely used to assess children’s behavioral and emotional problems. Items describe behavior of children over the prior two months, using a three-point scale (0 = not true; 1 = somewhat or sometimes true; 2 = very true or often true of the child). The CU behavior score measure comprised five items (e.g., shows lack of guilt after misbehavior, seems unresponsive to affection), previously validated in this sample and shown to factor separately from other dimensions (i.e., opposition and ADHD symptoms) within the broadband externalizing domain (see Waller et al., 2015 for factor analytic modeling). The reliabilities of the CU behavior subscale for mother-report (α = .59) and father-report (α = .55) were low, but consistent with previously reported alphas by other studies using the same five CU behavior items (α = .65, Willoughby et al., 2011; α = .55, Willoughby et al., 2014) and using a five-item deceitful-callous scale with two overlapping items (α = .64, Hyde et al., 2013). Mother and father reports of CU behavior showed moderate convergence (r = .35, p < .01) and thus their reports were averaged to utilize multiple informants (α = .66).

Theory-of-Mind

Children’s ToM understanding was assessed with the False Belief Prediction and Explanation Tasks-Revised (Bartsch & Wellman, 1989) at T1. Children were shown four vignettes where the location of a desired object was switched while the story protagonist was unaware. Experimenters then asked children to predict and explain choices of the protagonists about locations of objects. For each vignette, children answered where the protagonist would look for the object (prediction task) and why the protagonist searched in the wrong place (explanation task). A ToM composite score was computed by summing the number of correct responses, for a maximum score of 8. Based on a random sample of 15 cases, the reliability of scoring was .97.

Fearful/inhibited temperament

Mothers and a subsample of fathers completed an abbreviated 195-item version of Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Ahadi, Rothbart, & Ye, 1993) to report the child’s temperament using a seven-point scale (ranging from 1 = extremely untrue, to 7 = extremely true) at T1. We created a fearful/inhibited temperament scale by combining items from the Shyness (13 items; αs = .92–.93; e.g., ‘Gets embarrassed when strangers pay a lot of attention to her/him’) and Fearfulness subscales of the CBQ (13 items; αs = .73; e.g., ‘is afraid of loud noises’). As with the CU behavior scale, mother and father reports had a moderately high level of convergence (r = .57, p < .01) and thus were averaged.

Externalizing problems (teacher-report)

At T1, preschool teachers completed the Caregiver-Teacher Report Form for ages 1.5–5 (CTRF; Achenbach, 1997). To control for auto-regressive effects in the current analysis, the broadband externalizing problems scale (37 items of the original 40 items that excluded items that overlapped with the CU behavior measure; α = .96) was used, which consists of the attention problems and aggressive behavior subscales. At T2 and T3, teachers completed the Teacher Report Form for ages 6–18 (TRF/6-18, Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2002). The broadband externalizing problem scale, which includes the rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior subscales (31 of the original 32 items excluded the one overlapping item with the CU behavior measure; Mα= .94) at T2 and T3, were tested as separate outcome variables in the current study.

Covariates

At T1, information on child gender, age, and family income was collected via parent interview, and children’s verbal IQ was assessed with the Vocabulary subtest of Wechsler’s Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised (Wechsler, 1989). We included these covariates to control for potential effects of these variables on externalizing problems, as well as well-established links between ToM and verbal IQ and between age and ToM.

Results

First, in preliminary analyses, we explored descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among all study variables (Table 1). Higher levels of CU behavior were associated with more externalizing problems at all three time points. In contrast, lower ToM was associated with more externalizing problems only concurrently at age three. Fearful/inhibited temperament was unrelated to other study variables. We found moderate correlations between teacher reports of externalizing problems from age three, six, to 10, suggesting some stability of externalizing problems across childhood despite the changing informant.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations between Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1 Callous-Unemotional (P, T1) | - | |||||

| 2 Theory-of-Mind (O, T1) | −.12† | - | ||||

| 3 Fearful/Inhibited (P, T1) | .09 | .03 | - | |||

| 4 Externalizing (T, T1) | .11 | −.21** | −.07 | - | ||

| 5 Externalizing (T, T2) | .27*** | −.13† | −.10 | .32*** | - | |

| 6 Externalizing (T, T3) | .28*** | −.08 | −.01 | .33*** | .54*** | - |

|

| ||||||

| Range | 0–1.6 | 0–8 | 3.6–11.7 | 0–52 | 0–47 | 0–29 |

| M | .29 | 1.60 | 7.18 | 9.31 | 4.27 | 3.16 |

| SD | .27 | 2.10 | 1.51 | 10.27 | 6.99 | 5.37 |

Note. P = parent reported; O = observed; T = teacher reported

T1 = time 1 (age 3); T2 = time 2 (age 6); T3 = time 3 (age 10)

p < .10,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Second, using hierarchical multiple regression analyses, we examined whether age three CU behavior, ToM, or fearful/inhibited temperament uniquely contributed to later child externalizing problems at ages six or 10, controlling for the contributions of child age, gender, verbal IQ, family income, as well as externalizing problems at age three. We also explored the potential moderating effects of ToM and fearful/inhibited temperament on the associations between CU behavior and later externalizing problems. We created interaction terms between CU behavior and ToM and between CU behavior and fearful/inhibited temperament after centering all variables. For each regression model, demographic variables (i.e., child age, gender, verbal IQ, family income) and teacher-reported externalizing problems at age three were entered as covariates in Step 1. Next, CU behavior, ToM, and fearful/inhibited temperament were entered in Step 2. Finally, two-way interactions between CU behavior and the moderators were entered in Step 3. We also tested the three-way interaction among CU behavior, ToM, and fearful/inhibited temperament by entering it in Step 4, but this term was not significant in both regression models predicting age six and 10 externalizing behavior and thus it was subsequently dropped from the final models for parsimony.

Table 2 presents a summary of the multiple regression models. CU behavior significantly predicted increases in externalizing problems from age three to six, and from age three to 10, controlling for age three externalizing problems, and over and above the effects of fearful/inhibited temperament and ToM, as well as demographic covariates. Both ToM and fearful/inhibited temperament moderated links between CU behavior and externalizing problems. The interaction between CU behavior and ToM at age three significantly predicted externalizing problems at both age six and 10. In addition, the interaction between CU behavior and fearful/inhibited temperament was significant in the prediction of externalizing problems at age six. Although not included in the final model, we also tested all main and interaction effects predicting externalizing problems at age 10 while controlling for externalizing problems at age six. The main effect of CU behavior at age three remained significant and the interaction between CU behavior and ToM showed a trend level significance. Two-way interactions between ToM and fearful/inhibited temperament did not predict externalizing problems at age six and 10.

Table 2.

Parent-reported CU, ToM, and Fearful/Inhibited Temperament at T1 Predicting Teacher-reported Externalizing at T2 and T3

| EXT (T2) | EXT (T3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔR2 | b(SE) | β | ΔR2 | b(SE) | β | |

| Step 1: Covariates | .15*** | .17*** | ||||

| EXT | .19(.04) | .27*** | .16(.03) | .30*** | ||

| Age | −.10(.20) | −.03 | −.19(.16) | −.08 | ||

| Gender | −1.47(.87) | −.11† | −1.88(.68) | −.18** | ||

| Income | −.44(.15) | −.19** | −.17(.12) | −.10 | ||

| Vocab | .15(.13) | .07 | .19(.10) | .12* | ||

| Step 2: Main effects | .07*** | .06*** | ||||

| CU | 6.56(1.56) | .27*** | 4.81(1.25) | .24*** | ||

| ToM | −.14(.21) | −.04 | .04(.17) | .02 | ||

| Fear/BI | −.55(.27) | −.12* | −.01(.22) | −.004 | ||

| Step 3: Interaction effects | .04** | .02* | ||||

| CU × ToM | −1.89(.97) | −.13* | −1.54(.78) | −.14* | ||

| CU × Fear/BI | −2.50(1.10) | −.14* | −.20(.88) | −.02 | ||

Note. CU = parent reported callous-unemotional; Fear/BI = parent reported fearful/inhibited temperament; ToM = Observed Theory-of-Mind; EXT = teacher reported externalizing; Gender 0 = boys, 1 = girls. T2 = time 2 (age 6); T3 = time 3 (age 10).

p < .10,

p ≤ .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

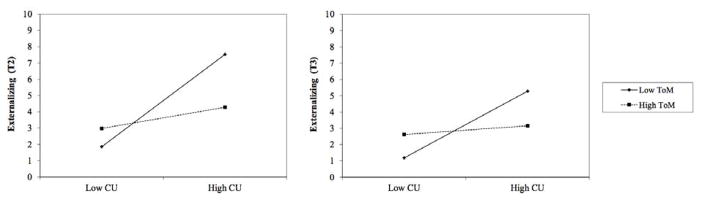

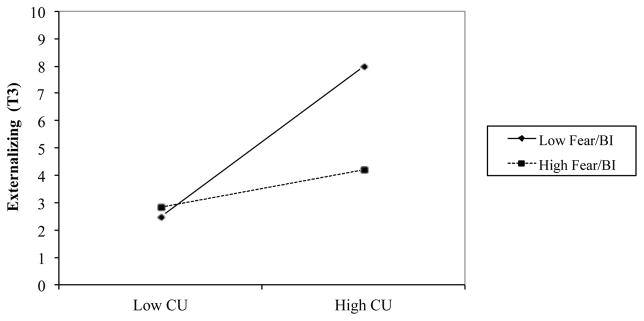

To explore the significant interactions, we followed the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991) for testing and plotting simple slopes at 1 SD below (low) and 1 SD above (high) the mean of the moderating variable. We also examined regions of significance to provide values of the moderators for which simple slopes were statistically significant (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). In the interaction between CU behavior and ToM, we found that there was a significant effect of age three CU behavior on more externalizing behavior at age six when children had low levels of ToM, b = 10.30 (2.16), t = 4.76, p < .01, but not when they had high levels of ToM, b = 2.36 (2.81), t = 0.84, ns (Figure 1)1. The region of significance indicated that the slope of age six externalizing problems regressed on CU behavior was significantly different from zero for scores of ToM below 4 (maximum of 8), which included 81% of the sample. Similarly, age three CU behavior significantly predicted higher externalizing problems at age 10 only when children showed low levels of ToM, b = 7.44 (1.68), t = 4.43, p < .01, but not when they showed high levels of ToM, b = 0.97 (2.18), t = 0.45, ns (Figure 1). The region of significance showed that the slope was significant for scores of ToM below 3, which included 72% of the sample. Finally, the interaction between CU behavior and fearful/inhibited temperament revealed that high CU behavior at age three predicted more externalizing problems at age six when children displayed low levels of fearful/inhibited temperament, b = 10.09 (2.40), t = 4.20, p < .001, but not when they showed high levels of fearful/inhibited temperament, b = 2.53 (2.04), t = 1.24, ns (Figure 2). The region of significance analysis indicated that the slope was significant for values of fearful/inhibited temperament below 8.3 (maximum of 11.72), which included 76% of the sample.

Figure 1.

ToM moderates the association between parent-reported CU behavior at T1 (age 3) and teacher-reported externalizing problems at T2 (age 6) and T3 (age 10). For T2, the slope for low ToM is significantly different from zero, b = 10.30 (2.16), t = 4.76, p < .01, but not for high ToM, b = 2.36 (2.81), t = 0.84, ns. For T3, the slope for low ToM is significantly different from zero, b = 7.44 (1.68), t = 4.43, p < .01, but not for high ToM, b = 0.97 (2.18), t = 0.44, ns.

Figure 2.

Fearful/inhibited temperament moderates the association between parent-reported CU at T1 (age 3) and teacher-reported externalizing problems at T2 (age 6). The slope for low fear/inhibited temperament is significantly different from zero, b = 10.09 (2.40), t = 4.20, p < .01, but not for high fear/inhibited temperament, b = 2.53 (2.04), t = 1.24, ns.

Discussion

The current study provides further evidence to support a robust association between early childhood CU behavior and externalizing problems in both middle and late childhood, over and above stability in externalizing problems, and across informants and settings. Moreover, the current study demonstrated that the link between CU behavior and externalizing problems appears to be moderated by other, key child-level characteristics. Specifically, we found that high levels of CU behavior predicted increased externalizing problems when children had low levels of ToM, but not when they had high ToM. The significant interaction between fearful/inhibited temperament and CU behavior also provides preliminary evidence to suggest that high levels of CU behavior may predict externalizing problems more strongly when children have lower temperamental fear and behavioral inhibition. We discuss each of these findings in relation to our main hypotheses and outline implications for identifying heterogeneous pathways to school-aged problems.

First, in line with our hypothesis, higher levels of parent-reported CU behavior at age three predicted more teacher-reported externalizing problems at both age six and age 10, even when controlling for externalizing problems at age three, and accounting for the effects of ToM and fearful/inhibited temperament. This finding is consistent with other studies that have demonstrated the unique contribution of early preschool-age CU behavior to more externalizing problems in later childhood (e.g., Kimonis et al., 2006; Willoughby et al., 2014) and an earlier study in the current sample (Waller et al., 2015). These findings highlight the importance of examining early childhood CU behavior as a unique risk factor for particularly severe and persisting externalizing problems throughout childhood, which potentially could be used for targeting preschoolers who require early preventive support (e.g., Dadds, Cauchi, Wimalaweera, Hawes, & Brennan, 2012; Waller, Gardner, & Hyde, 2013).

Second, consistent with some previous studies (Hughes et al., 2000; Olson et al., 2011), we found that low levels of ToM were not uniquely related to higher externalizing problems when accounting for the effect of early CU behaviors. However, the interaction between CU behavior and ToM did predict more externalizing problems. We corroborated this interaction effect when externalizing problems were assessed at early school-age (age six) and again at the transition to early adolescence (age 10; i.e., by different teachers and at different developmentally important ages). Our robust interaction effects across the elementary years supports the notion that low ToM alone may not be sufficient for explaining increased risk for externalizing behaviors, but could have enduring social consequences for children in the context of other behavioral or emotional risk factors (i.e., CU behavior). Thus, particularly within young children with high CU behavior, more mature cognitive empathy (i.e., high levels of ToM) may alleviate risk for developing aggressive or rule-breaking behaviors. Interventions that target cognitive empathy and perspective-taking may therefore help to reduce the likelihood that children with high CU behavior will go on to exhibit persisting externalizing problems. For example, within intervention efforts, one way to foster children’s cognitive empathy might be guiding parents to use more inductive reasoning (i.e., using child-centered explanation of the consequences of certain behavior on others) or develop their mind-mindedness (i.e., thinking about and talking to the child in psychological terms), that are reported to be conducive to children’s early ToM development (Hughes, 2011; Ruffman, Slade, & Crowe, 2002).

Third, providing some support for our hypothesis, although we did not find that fearful/inhibited temperament independently predicted later externalizing problems, the interaction between fearful/inhibited temperament and CU behavior predicted outcomes at age six but not age 10. Therefore, our results are consistent with the idea that emotional characteristics such as low fear and shyness may moderate pathways to more severe externalizing problems, particularly among children with high CU behavior, but this effect may only last through early school-age. This finding is consistent with a previous study which found that among school-aged children with high CU behavior, a group with high levels of conduct problems displayed lower behavioral inhibition compared to the group with low conduct problems (Fanti et al., 2015). Similar to ToM, low levels of fearful/inhibited temperament could predict increasing externalizing problems only in the presence of other temperamental characteristics, such as CU behavior. In particular, the finding of a combination of a low fearful/inhibited temperament and high CU behavior leading to higher levels of externalizing problems shows some parallels with the triarchic theory of psychopathy, which proposes that interactions among three core phenotypic components of psychopathy—disinhibition, boldness, and meanness—yield various manifestations of psychopathic traits and antisociality (Patrick et al., 2009). These findings suggest that other child features might shed light on possible moderating mechanisms explaining the multifinality of CU behavior in that why some children with CU behavior engage in more persistent externalizing problems, whereas other children do not.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study had several strengths including the multi-informant methods, observational assessment of ToM, and the prospective longitudinal design utilizing three time points across seven years. Use of observational assessments and mother-, father-, and teacher-reported measures helps to reduce the potential issue of shared method variance. Also, the current study focused on the predictive effects of child characteristics during the early preschool years for externalizing problems across childhood, which has implications for early prevention and intervention. The results from our community-based sample that is enriched for early child externalizing problems and includes both boys and girls contributes to the relatively little research on CU behavior and externalizing problems in non-clinically referred, non-forensic samples. At the same time, however, because the participating families were mostly middle-class white with intact family structure, the generalizability of the findings may be limited to those experiencing low risk. Also, the five-item CU behavior using items drawn from the CBCL can only be considered a home-grown measure that was not originally developed to assess the CU behavior construct. Although its predictive and construct validity has been supported in a previous study in the current sample (Waller et al., 2015), there may still be a limitation in the range of responses and thus it would be informative to examine whether the convergence of these items and interactions with ToM and temperamental features are stronger in forensic or clinical populations. Finally, the current study did not directly measure children’s ASD symptomatology to control for its potential overlap with the CU behavior construct or confounding effects on links between CU behavior and later externalizing problems. Nevertheless, none of participating children were reported to be diagnosed with an ASD, and all models stringently controlled for earlier broadband externalizing problems and verbal IQ, which partly alleviates the concerns about the robustness of the unique effect of earlier CU behavior on later externalizing problems.

Conclusions and Implications

Our findings suggested that CU behavior in early childhood is an important risk factor for externalizing problems in both middle and late childhood. We also demonstrated that examining other child characteristics could further increase the precision in identifying different developmental pathways to later externalizing problems among children with high levels of CU behavior. In particular, children’s cognitive empathy (i.e., ToM) and fearful/inhibited temperament during the preschool period appear to play important moderating roles in the link between early CU behavior and later externalizing problems. When high levels of CU behavior were combined with low levels of ToM or low fearful/inhibited temperament, they were associated with more severe externalizing behavior outcomes later on, whereas higher levels of ToM appeared to reduce the risk that high CU behavior would predict worse outcomes. These findings affirm recent calls for increasingly personalized preventive intervention according to specific child characteristics (see Hyde, Waller, & Burt, 2014; Waller et al., 2013).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant #R01MH57489 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Sheryl L. Olson. We are very grateful to the children, parents, teachers, and preschool administrators who participated, and to the many individuals who helped with data collection and management. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Some findings reported in full here were presented at the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD) in Philadelphia, PA, USA in March 2015.

Footnotes

We chose to explore ToM as a moderator of the relationship between CU behavior and later externalizing problems. However, we acknowledge that an alternative conceptualization of these models is to consider CU behavior as the moderator. In this case, when probing the interaction term, we find a trend-level negative effect of ToM at age 3 on later externalizing problems at age 6 only when children had high levels of CU behavior, b = −.77 (.39), t = −1.97, p < .10, but not when they had low levels of CU behavior, b = .27 (.27), t = 0.99, ns. While interesting to consider CU behavior as a moderator, especially to explain the inconsistent findings that have been reported by studies examining the relationship between ToM and later externalizing problems (Hughes et al., 2000; Olson et al., 2011), we note that our goal was to examine early CU behavior as a predictor and the potential emotional and cognitive moderating factors that influenced the strength of its relationship with later externalizing problems.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/2–3 and 1992 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Teacher/caregiver report form for ages 2–5. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. Ten-year comparisons of problems and competencies for national samples of youth: Self, parent and teacher reports. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2002;10:194–203. doi: 10.1177/10634266020100040101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ahadi SA, Rothbart MK, Ye R. Children’s temperament in the US and China: Similarities and differences. European Journal of Personality. 1993;7:359–377. doi: 10.1002/per.2410070506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB, van de Schoot R, Denissen JA, Hutteman R. Reducing bias due to systematic attrition in longitudinal studies: The benefits of multiple imputation. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2014;38:453–460. doi: 10.1177/0165025414542713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astington JW. The future of theory-of-mind research: Understanding motivational states, the role of language, and real-world consequences. Child Development. 2001;72:685–687. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astington JW. Sometimes necessary, never sufficient: False-belief understanding and social competence. In: Repacholi B, Slaughter V, editors. Individual differences in theory of mind: Implications for typical and atypical development. New York, NY, US: Psychology Press; 2003. pp. 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch K, Wellman H. Young children’s attribution of action to beliefs and desires. Child Development. 1989;60:946–964. doi: 10.2307/1131035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JM, Lilienfeld SO, Reddy SD, Latzman RD, Roose A, Craighead LW, … Raison CL. The inventory of callous and unemotional traits: A construct-validational analysis in an at-risk sample. Assessment. 2013;20:532–544. doi: 10.1177/1073191112474338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RR. A cognitive developmental approach to morality: Investigating the psychopath. Cognition. 1995;57:1–29. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00676-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RR. Responsiveness to distress cues in the child with psychopathic tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;27:135–145. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00231-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. The continuity of maladaptive behavior: From description to understanding in the study of antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 2: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. pp. 472–511. [Google Scholar]

- Choe DE, Lane JD, Grabell AS, Olson SL. Developmental precursors of young school-age children’s hostile attribution bias. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:2245–2256. doi: 10.1037/a0032293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Cauchi AJ, Wimalaweera S, Hawes DJ, Brennan J. Outcomes, moderators, and mediators of empathic-emotion recognition training for complex conduct problems in childhood. Psychiatry Research. 2012;199:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Hawes DJ, Frost AD, Vassallo S, Bunn P, Hunter K, Merz S. Learning to ‘talk the talk’: The relationship of psychopathic traits to deficits in empathy across childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:599–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Salmon K. Punishment insensitivity and parenting: Temperament and learning as interacting risks for antisocial behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:69–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1023762009877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD. Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:1146–1158. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development. 2008;79:1907–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Sasagawa S, Frick PJ. Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment. 2006;13:454–469. doi: 10.1177/1073191106287354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanti KA, Panayiotou G, Lazarou C, Michael R, Georgiou G. The better of two evils? Evidence that children exhibiting continuous conduct problems high or low on callous–unemotional traits score on opposite directions on physiological and behavioral measures of fear. Development and Psychopathology. 2015 doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000371. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein L, Bynner J. Continuity and discontinuity in middle childhood: Implications for adult outcomes in the UK 1970 birth cohort. In: Huston AC, Ripke MN, editors. Developmental contexts in middle childhood: Bridges to adolescence and adulthood. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 327–349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC, Kochanska G. Temperament as a moderator of pathways to conscience in children: The contribution of electrodermal activity. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:788–795. doi: 10.1017/S0048577200981848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Cornell AH, Bodin SD, Dane HE, Barry CT, Loney BR. Callous-unemotional traits and developmental pathways to severe conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:246–260. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Kahn RE. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Viding E. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1111–1131. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, White SF. Research review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF, Payne A, Chadwick A. Peer relations in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:84–108. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C. Social understanding and social lives: From toddlerhood through to the transition to school. New York, NY, US: Psychology Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Dunn J, White A. Trick or treat? Uneven understanding of mind and emotion and executive dysfunction in ‘hard-to-manage’ preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:981–994. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Ensor R. Behavioural problems in 2-year-olds: Links with individual differences in theory of mind, executive function and harsh parenting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:488–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, White A, Sharpen J, Dunn J. Antisocial, angry, and unsympathetic: ‘Hard-to-manage’ preschoolers’ peer problems and possible cognitive influences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:169–179. doi: 10.1017/S0021963099005193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Cheong J, Dishion TJ, Wilson M. Dimensions of callousness in early childhood: Links to problem behavior and family intervention effectiveness. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:347–363. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Waller R, Burt SA. Commentary: Improving treatment for youth with callous–unemotional traits through the intersection of basic and applied science—Reflections on Dadds et al. (2014) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:781–783. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AP, Happé FE, Gilbert F, Burnett S, Viding E. Feeling, caring, knowing: Different types of empathy deficit in boys with psychopathic tendencies and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:1188–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DR, Lopez NL, Olson SL, Sameroff AJ. Parental discipline and externalizing behavior problems in early childhood: The roles of moral regulation and child gender. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:369–383. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000030291.72775.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Frick PJ, Boris NW, Smyke AT, Cornell AH, Farrell JM, Zeanah CH. Callous-unemotional features, behavioral inhibition, and parenting: Independent predictors of aggression in a high-risk preschool sample. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;15:745–756. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9047-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Frick PJ, Cauffman E, Goldweber A, Skeem J. Primary and secondary variants of juvenile psychopathy differ in emotional processing. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(3):1091–1103. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Skeem JL, Cauffman E, Dmitrieva J. Are secondary variants of juvenile psychopathy more reactively violent and less psychosocially mature than primary variants? Law and Human Behavior. 2011;35:381–391. doi: 10.1007/s10979-010-9243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingzell I, Fanti KA, Colins OF, Frogner L, Andershed A, Andershed H. Early childhood trajectories of conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits: The role of fearlessness and psychopathic personality dimensions. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N. Children’s conscience and self-regulation. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1587–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Gross JN, Lin M, Nichols KE. Guilt in young children: Development, determinants, and relations with a broader system of standards. Child Development. 2002;73:461–482. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental propensity model of the origins of conduct problems during childhood and adolescence. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 76–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise EA, Arsenio WF. An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development. 2000;71:107–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow MT, Hubbard JA, McAuliffe MD, Rubin RM, Dearing KF. Childhood aggression, depressive symptoms, and peer rejection: The mediational model revisited. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30:240–248. doi: 10.1177/0165025406066757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2004;69(4) doi: 10.1111/j.0037-976x.2004.00312.x. Serial No. 278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Lopez-Duran N, Lunkenheimer ES, Chang H, Sameroff AJ. Individual differences in the development of early peer aggression: Integrating contributions of self-regulation, theory of mind, and parenting. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:253–266. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Kerr DCR, Lopez NL, Wellman HM. Developmental foundations of externalizing problems in young children: The role of effortful control. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:25–45. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nions E, Sebastian CL, McCrory E, Chantiluke K, Happé F, Viding E. Neural bases of Theory of Mind in children with autism spectrum disorders and children with conduct problems and callous–unemotional traits. Developmental Science. 2014;17:786–796. doi: 10.1111/desc.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Lochman JE, Powell N. The development of callous-unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: Are there shared and/or unique predictors? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:319–333. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich DS, Dadds MR, Hawes DJ. Cognitive and affective empathy in children with conduct problems: Additive and interactive effects of callous–unemotional traits and autism spectrum disorders symptoms. Psychiatry Research. 2014;219:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Fowles DC, Krueger RF. Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:913–938. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffman T, Slade L, Crowe E. The relation between children’s and mothers’ mental state language and theory-of-mind understanding. Child Development. 2002;73:734–751. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA. From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC, US: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE. The development of aggressive behaviour during childhood: What have we learned in the past century? International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24:129–141. doi: 10.1080/016502500383232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW. What are the associations between parenting, callous–unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Hyde LW, Grabell AS, Alves ML, Olson SL. Differential associations of early callous-unemotional, oppositional, and ADHD behaviors: multiple domains within early-starting conduct problems? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12326. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Wright AC, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Hyde LW. Factor structure and construct validity of the parent-reported inventory of callous-unemotional traits among high-risk 9-year-olds. Assessment. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1073191114556101. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Preschool and primary scale of intelligence–Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman HM. Making minds: How theory of mind develops. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman HM, Cross D, Watson J. Meta-analysis of theory-of-mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development. 2001;72:655–684. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman HM, Harris PL, Banerjee M, Sinclair A. Early understanding of emotion: Evidence from natural language. Cognition and Emotion. 1995;9:117–149. doi: 10.1080/02699939508409005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Mills-Koonce WR, Gottfredson NC, Wagner NJ. Measuring callous unemotional behaviors in early childhood: Factor structure and the prediction of stable aggression in middle childhood. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2014;36:30–42. doi: 10.1007/s10862-013-9379-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Waschbusch DA, Moore GA, Propper CB. Using the ASEBA to screen for callous unemotional traits in early childhood: Factor structure, temporal stability, and utility. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2011;33:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9195-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]