Abstract

Background and Objectives

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of vilazodone, a selective serotonin receptor inhibitor and partial 5-HT1A agonist, for treatment of cannabis dependence.

Methods

Seventy-six cannabis-dependent adults were randomized to receive either up to 40 mg/day of vilazodone (n=41) or placebo (n=35) for eight weeks combined with a brief motivational enhancement therapy intervention and contingency management to encourage study retention. Cannabis use outcomes were assessed via weekly urine cannabinoid tests; secondary outcomes included cannabis use self-report and cannabis craving.

Results

Participants in both groups reported reduced self-reported cannabis use over the course of the study; however, vilazodone provided no advantage over placebo in reducing cannabis use. Men had significantly lower creatinine-adjusted cannabinoid levels and a trend for increased negative urine cannabinoid tests than women.

Discussion and Conclusions

Vilazodone was not more efficacious than placebo in reducing cannabis use. Important gender differences were noted, with women having worse cannabis use outcomes than men.

Scientific Significance

Further medication development efforts for cannabis use disorders are needed, and gender should be considered as an important variable in future trials.

Introduction

Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. Although its use and potential health consequences are widespread and basic science research on cannabinoids is well developed, research aimed at the treatment of cannabis use disorders has lagged behind. Few specific treatments have been developed for cannabis use disorders, and pharmacotherapy, in particular, has received little attention1–4.

Multiple preclinical studies implicate cannabinoid interactions with the serotonin system, suggesting a potential target for medication development for cannabis use disorders5–8. However, clinical investigations of the utility of serotonergic medications for treatment of cannabis dependence have had mixed results. Buspirone, a partial 5-HT1A agonist, reduced percentage of positive urine drug screens among treatment completers in a pilot study, and a trend was observed for a lower percentage of positive drug screens in the entire sample9. A larger follow-up study, though, did not find a medication effect on cannabis use outcomes, and reported worse outcomes with buspirone treatment in women10. Fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), significantly reduced cannabis use in depressed, adult alcohol-dependent individuals11; however, a trial in adolescents and young adults with comorbid major depression and cannabis use disorders did not find a significant effect of fluoxetine on cannabis-related outcome measures12. Similarly, a recent trial of the SSRI escitalopram in cannabis dependent adults also failed to demonstrate an advantage of medication treatment13.

The current investigation was based on the hypothesis that a medication combining both 5-HT1A partial agonism and serotonin reuptake properties may hold more promise for treatment of cannabis use disorders than either a 5-HT1A partial agonist or SSRI medication alone. Vilazodone is a newly-available agent that combines the antidepressant activity of serotonin reuptake inhibition with partial agonist activity for 5-HT1A. Vilazodone has been FDA-approved for the treatment of acute episodes of major depressive disorder. Vilazodone has not been previously been evaluated as a potential treatment for cannabis dependence; however, given its dual serotonergic mechanism of action, it may be a promising pharmacotherapy.

Methods

This study was an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a flexible dose of vilazodone (up to 40 mg/day) in cannabis-dependent individuals conducted between August, 2012 and August, 2014. Participants were primarily recruited through media and internet advertisements.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board. All participants gave written, informed consent prior to study participation.

To be eligible for participation, individuals had to be between 18 and 65 years of age and meet DSM-IV14 criteria for current cannabis dependence. Exclusion criteria included current dependence on any other substance (with the exception of caffeine and nicotine); history of psychotic, bipolar or eating disorder; current suicidal or homicidal risk; current treatment with psychoactive medication (with the exception of stimulants and non-benzodiazepine sedative/hypnotics) or CYP3A4 inhibitors; major medical illness or disease; pregnancy, lactation or inadequate birth control; and patients who, in the investigator’s opinion, would be unable to comply with study procedures or assessments. All potential participants received an evaluation for medical exclusions. The medical evaluation included a medical history, routine physical examination, blood chemistries, urine drug screen, and urine pregnancy test if indicated.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV)15 was used to assess for psychiatric exclusions. Cannabis use for the 90 days prior to study entry was estimated using the Time-Line Follow-Back (TLFB)16, and TLFB data were collected weekly throughout the study. Levels of cannabis craving were assessed at screening and weekly using the Marijuana Craving Questionnaire (MCQ)17. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A)18 and Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D)19 were administered at screening and weeks 1, 4, 6, and 8. Quantitative urine cannabinoid tests (UCTs) for cannabinoids were administered at screening and weekly throughout the study. UCTs were performed using the AXSYM® system from Abbott Laboratories, with a negative UCT defined as a value less than 50 ng/ml for cannabinoids.

Both groups received three adjunctive motivational enhancement therapy sessions (MET) during the study. The first MET session occurred prior to medication initiation and a second session occurred approximately one week later; a third session occurred at week 4. Participants completed a series of initial worksheets (Marijuana Use Summary Sheet, Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, Marijuana Problem Scale, Reasons for Quitting Questionnaire)20 from which personalized feedback reports (PFRs) were prepared. These PFRs were used to initiate session discussion regarding participants’ frequency of cannabis use, problems related to use, reasons for quitting use, high risk situations for continued or future use, and short and long-term goals related to reduction of use.

Urn randomization21 was used to determine treatment assignment. Randomization variables included gender and presence or absence of anxiety or depressive disorders. Vilazodone and placebo tablets were provided by Forest Pharmaceuticals. Medication was initiated at a dose of 10 mg daily for seven days, then increased to 20 mg daily for seven days followed by 40 mg daily as tolerated. Dosage adjustments were made as needed by qualified medical personnel. Medication side effects were evaluated weekly by a clinician by asking the participant open-ended questions such as “Have you had any problems or side effects since we saw you last (such as cold, flu, nausea, headache, or any other problem)?” The type of adverse event, severity of adverse event, relationship to study medication, action taken, and outcome were recorded. Medication compliance was reviewed weekly using patient report and pill count.

Participants received nominal weekly compensation for returned medication diaries, pill bottles, and unused pills ($10). In order to improve study retention, contingency management was used to reward weekly visit attendance. Participants received an escalating cash incentive starting at $5 and increasing by $5 each week, beginning at week 1, with any unexcused missed weekly visit resulting in a reset of the cash incentive to $5. In addition, participants received cash bonuses for completing week 1 ($20) and week 8 ($40).

Statistical Analysis

The primary hypothesis was that cannabis-dependent participants receiving vilazodone would have increased odds of submitting negative weekly UCTs during study treatment versus those receiving placebo during an 8-week randomized clinical trial. An intent-to-treat (ITT) approach including all randomized participants was used as the primary efficacy analysis. For the ITT analysis, those lost to follow-up or missing study visits were coded as urine drug screen failures. The study was powered to detect a 29% rate of negative UCTs in participants receiving vilazodone, compared with 11% in placebo participants taken over 8 weekly visits. These estimates were derived from a prior pilot trial to complement contingency management targeting cannabis dependence9. With 8 observations taken on each participant and a projected autocorrelation of 0.5, we would have 80% power with two-sided α=0.05 to detect the stated difference of 18% in proportions of negative UCTs with 24 participants per group. Assuming a 35% rate of attrition, the sample size was inflated to 38 participants per group.

Prior to the primary analysis, descriptive statistics were tabulated for all participants and compared between treatment groups. A Wilcoxon Rank sum test was used to compare continuous baseline demographic and clinical measures between treatment groups while the normal Pearson Chi-Square test was used to compare the relationship for categorical and ordinal variables (Fisher’s exact test was used where appropriate). The primary efficacy outcome of vilazodone versus placebo on the proportion of negative UCTs analyzed over the 8-week treatment period. A repeated measures logistic regression model using the methods of generalized estimating equations22 was applied to estimate the overall effect of vilazodone on test results during active treatment. Time from baseline to the first negative UCT was assessed between treatment groups using a Log Rank test. Creatinine-adjusted cannabinoid levels were examined during treatment between groups using a linear mixed effects model. Cannabinoid levels were measured weekly and adjusted for concurrently measured creatinine levels. Due to non-normality of model residuals, cannabinoid-creatinine ratios were natural logarithm transformed. Secondary analysis using generalized linear mixed effects models were developed to assess the effect of vilazodone on the number of reported weekly cannabis use sessions (log-linear), the amount of cannabis used (grams, natural logarithm transformed), and craving (Marijuana Craving Questionnaire; MCQ). Design adjusted study models contained randomized treatment assignment, study visit and baseline measures of the model outcome (where appropriate). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were independently tested for association with efficacy outcome and those associated were included as predictors in covariate adjusted models.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). Results are presented as odds ratios/hazard ratios or mean responses with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Significance was set at a 2-sided p-value of 0.05 and no corrections have been applied to presented p-values.

Results

Enrollment and Baseline Data

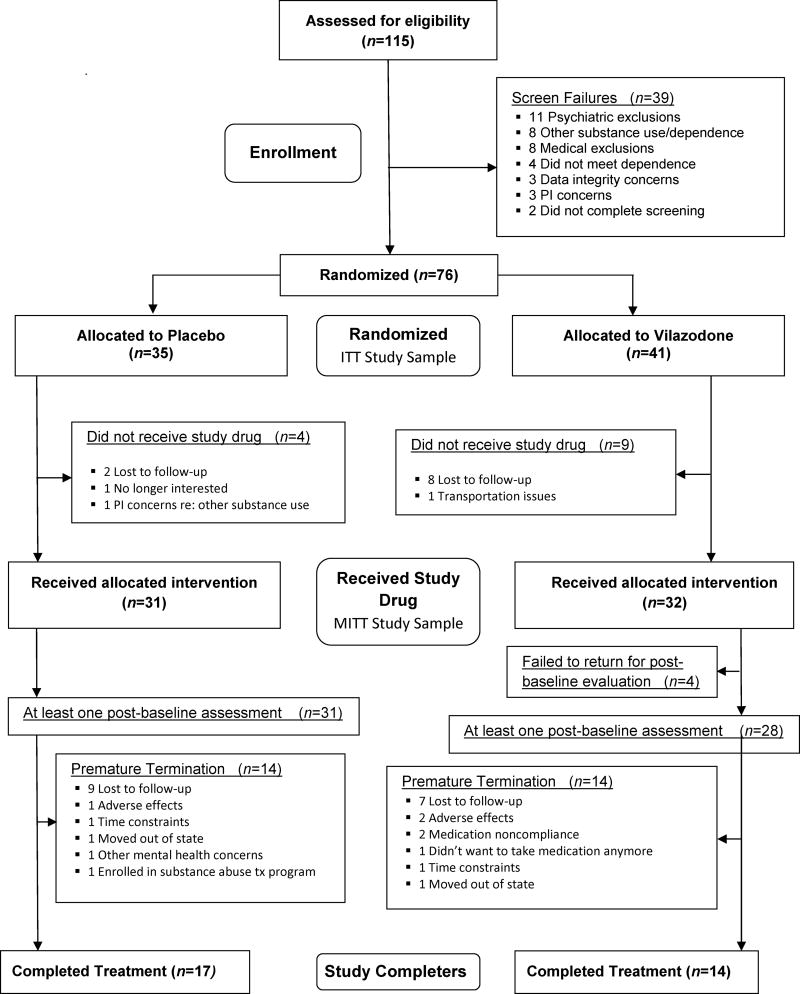

Enrollment occurred between August, 2012 and June, 2014, with 115 subjects screened for eligibility and 38 (33%) excluded (Figure 1). Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics for all randomized participants are shown in Table 1. Participants (n=76) averaged 22 years of age and were primarily male (n=60, 79%) and Caucasian (n=40, 55%). Participants randomized to receive placebo study medication had slightly higher urine cannabinoid levels at screening (Mean [95% CI]=764 [353–1176] vs. 1109 [649–1568]; p=0.047). Other demographics and baseline smoking measures were similar between the two randomized groups. Baseline characteristics were examined for univariate associations with cannabis use outcomes. Increased amount and frequency of cannabis use in the 30 days prior to the study was significantly associated with increased urine cannabinoid levels during treatment (total sessions p=0.006; sessions per day p=0.012; ounces per week p=0.0145; joints per day p=0.033). Although not statistically significant, gender was moderately associated with cannabinoid levels during study treatment with males having lower values as compared to females (p=0.073). Increased amount of cannabis use prior to the study was not associated with increased odds of negative UCTs during treatment (p>0.20). However, the percent of days using cannabis prior to study was associated with decreased odds to attain weekly abstinence during study treatment (OR=0.91 [0.84–0.98] p=0.017).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram and flowchart (ITT: Intent to treat; MITT: Modified intent to treat)

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics. Continuous characteristics are noted as Mean and associated 95% confidence interval and categorical Characteristics are noted as % (n).

| Variable | Overall N=76 |

Vilazodone N=41 |

Placebo N=35 |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| Age | 22.2 (21.3–23.1) | 22.6 (21.3–23.9) | 21.7 (20.4–23.1) | 0.228 |

| Male | 60 (79.0) | 30 (73.2) | 30 (85.7) | 0.182 |

| Caucasian | 40 (54.8) | 19 (47.5) | 21 (63.6) | 0.168 |

| HS Graduate | 72 (94.7) | 38 (92.7) | 34 (97.1) | 0.618 |

| HAM-A | 2.3 (1.7–2.9) | 2.4 (1.6–3.2) | 2.2 (1.3–3.1) | 0.583 |

| HAM-D | 2.3 (1.8–2.8) | 2.3 (1.6–3.0) | 2.3 (1.5–3.1) | 0.954 |

| Cannabis Use Characteristics | ||||

| Age of Dependence Onset | 18.6 (18.1–19.1) | 18.4 (17.8–19.0) | 18.8 (18.0–19.7) | 0.642 |

| Percent of days Using | 81.9 (77.3–86.5) | 83.3 (77.1–89.4) | 80.3 (73.1–87.4) | 0.624 |

| Joints/bowls Per Day | 3.3 (2.8–3.9) | 3.1 (2.6–3.6) | 3.7 (2.7–4.7) | 0.958 |

| Cannab/Creatinine Ratio | 7.1 (4.3–9.8) | 4.8 (3.0–6.6) | 9.7 (4.1–15.3) | 0.183 |

| MCQ Total Score | 48.4 (44.8–51.9) | 49.9 (45.0–54.9) | 46.7 (41.5–51.9) | 0.311 |

| MCQ Compulsivity Score | 8.3 (7.2–9.5) | 8.4 (7.0–9.8) | 8.3 (6.5–10.1) | 0.497 |

| MCQ Emotionality Score | 11.5 (10.3–12.6) | 12.1 (10.5–13.8) | 10.7 (9.0–12.4) | 0.243 |

| MCQ Expectancy Score | 13.8 (12.9–14.8) | 14.1 (12.7–15.5) | 13.5 (12.1–14.9) | 0.429 |

| MCQ Purposefulness Score | 14.6 (13.6–15.7) | 15.0 (13.6–16.4) | 14.3 (12.6–15.9) | 0.576 |

data available on 74 participants (Placebo n=34 and Vilazodone n=40).

Study Retention and Medication Dosage

The study randomized 76 participants to receive either vilazodone (n=41) or placebo (n=35). Fifty-nine of the 76 randomized participants (77.6%) attended at least one treatment study visit and those randomized to placebo were moderately more likely to attend at least one visit (vilazodone 28/41 [68.3%] vs. placebo 31/35 [88.6%]; Fisher’s Exact p=0.050). Less than half of the randomized participants completed all study visits (overall: 31/76, 40.8%; X21=43.9, p<0.001; vilazodone 14/41 [34.2%] vs. placebo 17/35 [48.6%]; X21=1.6, p=0.202). Of the 608 scheduled visits for UCT collection, 54% of the visits were attended with successful sample collection (n=331). Participants randomized to receive placebo attended significantly more scheduled visits than those randomized to receive vilazodone (vilazodone 138/328 [42.1%] vs. placebo 193/280 [68.9%]; X21=43.9, p<0.001).

In participants that received at least one study dose of medication, the maximum dosage received by each participant was tabulated. The mean dose received was 32 (SD=13) mg (vilazodone: 25 [14]; placebo: 38[6]). Of those that received at least one medication dose, 68% (43/63) received the maximum possible dosage (40 mg) and 79% (50/63) received at least 20 mg. In those receiving at least one dose of vilazodone, 44% (14/32) received the maximum dosage while in the study and 63% (20/32) received at least 20 mg.

Efficacy

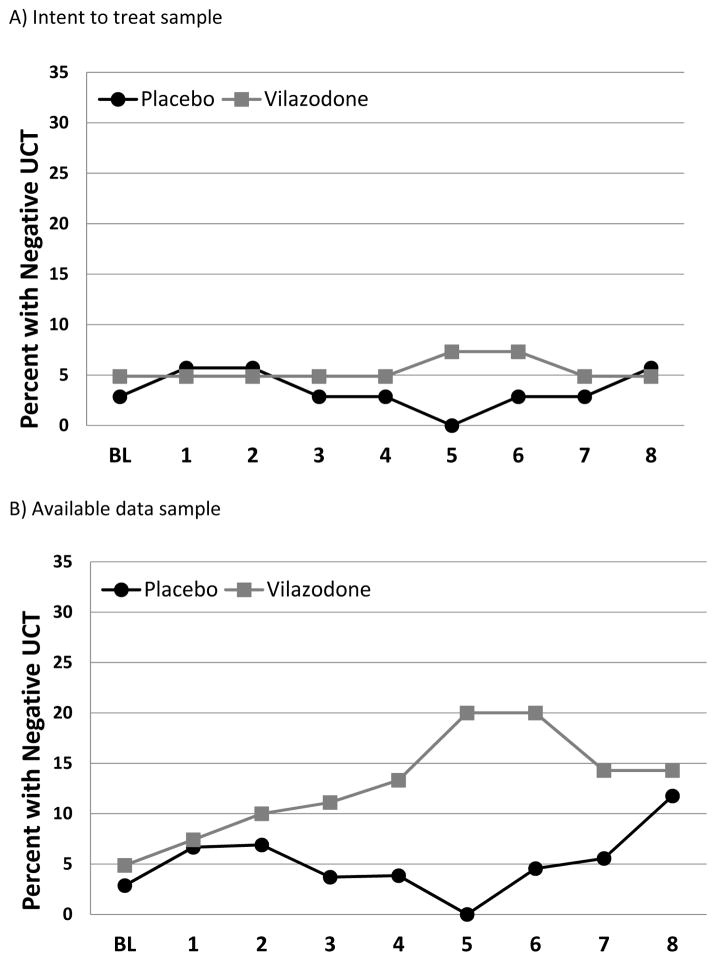

Due to significant study retention differences between randomized study groups, UCT results from both intent-to-treat (ITT) and available data analysis are presented. The proportion of negative UCTs in the vilazodone and placebo groups at each visit is shown in Figure 2 (intent-to-treat sample and available data). The proportion of negative weekly UCTs during the treatment phase of the study was 4.6% (28/608) (vilazodone=5.5% [18/328] and placebo=3.6% [10/280]). In the ITT analysis, there was no difference in the odds of a negative weekly UCT during treatment between those randomized to vilazodone and those to placebo (ITT: OR=1.22 [0.24–6.37]; p=0.810). In the analysis of available study data, participants in the vilazodone treatment group had greater than twice rate of negative UCTs as compared to placebo (vilazodone 18/138 [13.0%] vs. placebo 10/193 [5.2%], OR=2.65 [0.50–14.0], p=0.253); study completers had similar abstinence rates to the whole cohort (vilazodone 17/109 [15.6%] vs. placebo 9/130 [6.9%]; OR=2.17 [0.40–11.7], p=0.369). Four of the 76 randomized participants had negative UCT at the end of the 8 week study (vilazodone 2/41 [4.9%] vs. placebo 2/35 [5.7%], OR=0.85 [0.11–6.34], χ21=0.03, p=0.871). Although the rates of negative UCTs were low, time to the first negative UCT was examined between study groups. There was no significant effect of treatment with vilazodone on time until first negative UCT (Log Rank χ21=0.24, p=0.622).

Figure 2.

Proportion of participants with negative weekly UDS for A) Intent-to-treat and B) available data samples

Secondary outcome analysis included weekly creatinine-adjusted cannabinoid levels, weekly self-reported cannabis use sessions, and standardized amounts of cannabis use (grams). There was no significant treatment effect on the cannabinoid levels between the participants randomized to vilazodone as compared to placebo (β=−0.06 [−0.61, 0.48], t54=−0.23, p=0.823). Study participants reported weekly cannabis use frequency (use sessions) and amounts (grams) via TLFB taken at each visit. Treatment with vilazodone had no effect on the number of weekly reported cannabis use sessions (RR [95% CI]=1.02 [0.76–1.38], χ21=0.04, p=0.851). The vilazodone group reported an average of 10.0 marijuana use sessions per week while the placebo group reported 9.9 sessions per week. Although there was a significant decrease in the weekly amount of cannabis use (F7,258=10.5, p<0.001), there was no significant treatment effect on the amount (F1,57=0.3, p=0.561). In order to examine the effect of the differential dropout rate on reported use, an analysis of study completers was done with similarly null results for reported cannabis use sessions (RR [95% CI]=1.18 [0.72–1.92], χ21=0.44, p=0.507) and use amounts (F1,29=0.1, p=0.802). Craving was assessed using the MCQ total score as well as the subscale scores (purposefulness, emotionality, expectancy and compulsion). Participants randomized to receive vilazodone had moderately lower mean purposefulness subscale scores than those randomized to placebo (vilazodone=8.9±0.7 vs. placebo=11.3±0.7; F1,53=6.7, p=0.012).

Recent evidence suggests that gender may modify the efficacy of buspirone, a partial 5-HT1A agonist with properties similar to vilazodone, on cannabis abstinence outcomes10. Gender and gender by treatment group interactions were added to both primary and secondary efficacy outcome models and assessed for significant model interactions or confounding effects on the treatment efficacy estimate. Although not different at baseline (males Ln[Cannab]=1.06±0.17 creatinine-adjusted vs. females 1.38±0.32, p=0.374], during treatment males had significantly lower mean cannabinoid levels than females (Ln[Cannab]= 0.99±0.15 vs. 1.72±0.28, p=0.025). In the male cohort, those randomized to receive vilazodone had numerically lower cannabinoid levels than those randomized to placebo (0.86±0.24 versus 1.16±0.19) while the relationship was in the other direction in females (1.84±0.31 versus 1.17±0.36). Additionally, there was a moderately increased prevalence of negative UCTs in males as compared to females (5.6% [27–480] vs. 0.8% [1/128], p=0.079). Although males had an increase rate of negative UCTs as compared to females, when the primary efficacy analysis is restricted to males, the effect of treatment with vilazodone remains insignificant; stratified analysis in the female cohort could not be performed as due to an insufficient number of negative UCTs. Despite gender effects in the objective measures of cannabis intake, self-reported frequency and amount of cannabis use variables showed no significant impact of gender on outcomes, nor were there any significant gender by treatment interactions present. In regards to craving, a reduction in the Purposefulness subscale of the MCQ was evident in male participants randomized to vilazodone (vilazodone=7.0±0.7 vs. placebo=10.0±0.6; F1,42=8.9, p<0.001) but not in female participants (vilazodone=12.8±1.6 vs. placebo=12.0±1.8; F1,9=0.1, p=761). The MCQ total score and remaining subscale scores showed no effect of either treatment or gender.

Safety and Tolerability

Safety and tolerability were assessed at each study visit. A clinician evaluated adverse events with an open-ended interview and a comprehensive review of clinical measurements. A total of 96 events were reported in 25 participants in the vilazodone group and 73 events were reported in 28 participants in the placebo group during study treatment. The most commonly reported adverse events were headache and nausea; headache accounted for 12.5% and 13.7% of reported events in the vilazodone and placebo groups, respectively, while nausea accounted for 17.7% and 9.6%. Respiratory complaints, including upper respiratory infections, accounted for 8.3% of complaints in the vilazodone group and 20.5% of the complaints in the placebo group. Nearly all reported adverse events were rated mild to moderate (99.4%; 168/169). One adverse event rated as severe was reported in a patient randomized to receive placebo; the participant suffered from insomnia that existed prior to the study and was not made worse by treatment. No FDA defined serious adverse events were noted during study treatment.

Discussion

In this investigation, vilazodone did not demonstrate an advantage over placebo on cannabis use outcomes. Although self-reported amount of cannabis use decreased during the study in both treatment groups, the overall proportion of participants achieving abstinence was low. These findings add to the growing body of evidence that antidepressants and anxiolytics likely have limited value in the treatment of cannabis use disorders other than potentially for treatment of comorbid conditions. Recent investigations of fluoxetine12, nefazodone23, bupropion23, escitalopram13, and buspirone10 have also failed to demonstrate an effect on cannabis use outcomes.

The low levels of anxiety and depression reported by participants in the current trial preclude the conduct of analyses to determine if improvements in these domains may predict greater response to vilazodone treatment. In a previous trial with buspirone in cannabis dependent individuals9, anxiety severity over the course of the study was a significant predictor of UCT results with a main treatment effect. In contrast, an examination of venlafaxine-extended release for co-occurring cannabis dependence and depressive disorders found mood improvement to be associated with reduction in cannabis use in participants receiving placebo but not venlafaxine24. More work is needed to determine if anxiety and depression are clinically relevant targets for cannabis medication development.

Of interest, different trajectories of cannabis use were observed in men and women, with men having significantly lower creatinine-adjusted cannabinoid levels and a trend for increased negative UCTs than women. Although preliminary, these data are suggestive that cannabis dependent women may have greater difficulty in achieving cannabis cessation than cannabis dependent men. A recent analysis of human laboratory data found women to be more sensitive to the subjective effects related to the abuse liability of cannabis relative to men25, which could contribute to difficulty achieving abstinence. Further, cannabis withdrawal symptoms may contribute to difficulty achieving or maintaining abstinence, and more severe cannabis withdrawal symptoms have been reported in women26. Together, these findings support the importance of considering gender as a critical variable in treatment development for cannabis use disorders.

Limitations of the study included a small sample size and significant attrition during the course of the study. Although rates of study completion did not differ, participants randomized to placebo attended significantly more study visits than participants randomized to vilazodone treatment, which may reflect lower tolerability. UCT interpretation in clinical research is also difficult due to the long excretion half-life of cannabis in urine27. Lastly, as noted above, our analysis of gender differences was likely underpowered. As women are often underrepresented in pharmacotherapy studies for cannabis use disorders, future trials should recruit more women.

In conclusion, in this pilot trial vilazodone was not shown to be more efficacious than placebo in reducing cannabis use. Potentially important gender differences were noted, with women having worse cannabis use outcomes than men. Although it is possible that subsets of individuals with cannabis use disorders, such as those with more depression or anxiety symptoms, may respond more positively to vilazodone treatment, the characteristics of participants in this study preclude such analyses. These results underscore the need for further medication development efforts for cannabis use disorders, and more extensive investigation of the potential moderating effects of gender on cessation outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was provided by NIH grant R21DA34089 (McRae-Clark). Vilazodone and matching placebo were provided by Forest Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.McRae AL, Budney AJ, Brady KT. Treatment of marijuana dependence: a review of the literature. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:369–376. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordstrom BR, Levin FR. Treatment of cannabis use disorders: a review of the literature. Am J Addict. 2007;16:331–342. doi: 10.1080/10550490701525665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein AM, Gorelick DA. Pharmacological treatment of cannabis dependence. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:1351–1358. doi: 10.2174/138161211796150846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall K, Gowing L, Ali R, Le Foll B. Pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD008940. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008940.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes FV, Resstel LB, Guimaraes FS. The anxiolytic-like effects of cannabidiol injected into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis are mediated by 5-HT1A receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:465–473. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill MN, Sun JC, Tse MT, Gorzalka BB. Altered responsiveness of serotonin receptor subtypes following long-term cannabinoid treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9:277–286. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mato S, Vidal R, Castro E, Diaz A, Pazos A, Valdizan EM. Long-term fluoxetine treatment modulates cannabinoid type 1 receptor-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase in the rat prefrontal cortex through 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor-dependent mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:424–434. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanelati TV, Biojone C, Moreira FA, Guimaraes FS, Joca SR. Antidepressant-like effects of cannabidiol in mice: possible involvement of 5-HT1A receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:122–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McRae-Clark AL, Carter RE, Killeen TK, Carpenter MJ, Wahlquist AE, Simpson SA, Brady KT. A placebo-controlled trial of buspirone for the treatment of marijuana dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McRae-Clark AL, Baker NL, Gray KM, Killeen TK, Wagner AM, Brady KT, DeVane CL, Norton J. Buspirone treatment of cannabis dependence: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.013. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Haskett RF, Ehler JG, Jarrett PJ, Thase ME, Perel JM. Fluoxetine versus placebo for the marijuana use of depressed alcoholics. Addict Behav. 1999;24:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornelius JR, Bukstein OG, Douaihy AB, Clark DB, Chung TA, Daley DC, Wood DS, Brown SJ. Double-blind fluoxetine trial in comorbid MDD-CUD youth and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstein AM, Miller H, Bluvstein I, Rapoport E, Schreiber S, Bar-Hamburger R, Bloch M. Treatment of cannabis dependence using escitalopram in combination with cognitive-behavior therapy: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:16–22. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.819362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, D.C: 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- 15.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychological and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heishman SJ, Evans RJ, Singleton EG, Levin KH, Copersino ML, Gorelick DA. Reliability and validity of a short form of the Marijuana Craving Questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Psychiatry. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberg KL, Roffman RA, Carroll KM, McRee B, Babor TF, Miller M, Kadden R, Duresky D, Stephens R. Brief Counseling for Marijuana Dependence: A Manual for Treating Adults. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. (Vol. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4211) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;12(Suppl):70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpenter KM, McDowell D, Brooks DJ, Cheng WY, Levin FR. A preliminary trial: double-blind comparison of nefazodone, bupropion-SR, and placebo in the treatment of cannabis dependence. Am J Addict. 2009;18:53–64. doi: 10.1080/10550490802408936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin FR, Mariani J, Brooks DJ, Pavlicova M, Nunes EV, Agosti V, Bisaga A, Sullivan MA, Carpenter KM. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of venlafaxine-extended release for co-occurring cannabis dependence and depressive disorders. Addiction. 2013;108:1084–1094. doi: 10.1111/add.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper ZD, Haney M. Investigation of sex-dependent effects of cannabis in daily cannabis smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Copersino ML, Boyd SJ, Tashkin DP, Huestis MA, Heishman SJ, Dermand JC, Simmons MS, Gorelick DA. Sociodemographic characteristics of cannabis smokers and the experience of cannabis withdrawal. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:311–319. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.503825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eskridge KD, Guthrie SK. Clinical issues associated with urine testing of substances of abuse. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:497–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]