Abstract

Background and purpose — A criticism of total hip arthroplasty (THA) survivorship analysis is that revisions are a late and rare outcome. We investigated whether prolonged opioid use is a possible indicator of early THA failure.

Patients and methods — We conducted a cohort study of THAs registered in a total joint replacement registry from January 2008 to December 2011. 12,859 patients were evaluated. The median age was 67 years and 58% were women. Opioid use in the year after surgery was the exposure of interest, and the cumulative daily amounts of oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) were calculated. Post-THA OMEs per 90 day periods were categorized into quartiles. The endpoints were 1- and 5-year revisions.

Results — After the first 90 days, 27% continued to use opioids. The revision rate was 0.9% within a year and 1.7% within 5 years. Use of medium-low (100–219 mg), medium-high (220–533 mg), and high (≥ 534 mg) amounts of OMEs in days 91–180 after surgery was associated with a 6 times (95% confidence interval (CI): 3–15), 5 times (CI: 2–13), and 11 times (CI: 2.9–44) higher adjusted risk of 1 year revision, respectively. The use of medium-low and medium-high amounts of OMEs in days 181–270 after surgery was associated with a 17 times (CI: 6–44) and 14 times (95% CI: 4–46) higher adjusted risk of 1-year revision. There was a similar higher risk of 5-year revision.

Interpretation — Persistent postoperative use of opioids was associated with revision THA surgery in this cohort, and it may be an early indicator of potential surgical failures.

Despite generally favorable clinical results following total hip arthroplasty (THA), a proportion of patients have unfulfilled outcomes. Patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs), specifically Oxford hip scores 6 months after THA, have been reported to be associated with THA revision risk (Rothwell et al. 2010). Some challenges for PROMs collection include costs, data collection burden for both the collectors and participants, lack of internal validity and reliability in certain settings, and difficulty in obtaining good response rates (Alviar et al. 2011, Black 2013). Analgesic use may be an alternative indicator of persistent pain after THA.

While much work has been done on multi-modal pain protocols in the immediate postoperative period (Vendittoli et al. 2006, Ranawat and Ranawat 2007), there have been few studies looking into persistent opioid use after THA (Singh and Lewallen 2010). Part of the challenge in studying persistent narcotic use is the fact that patients may receive prescriptions from many healthcare providers.

In an integrated healthcare system, pharmacy records can be accessed and linked to individual patients who have undergone THA, to determine whether some patients continue to receive opioids. The main aim of the present study was to identify and describe the use of opioids by patients up to a year after THA. A secondary aim was to evaluate whether use of opioids in the year after their surgery was associated with a higher risk of short-term (1-year) and medium-term (5-year) revision THA.

Patients and methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients who underwent THA procedures between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011 at Kaiser Permanente. Kaiser Permanente is an integrated healthcare system with over 10 million members throughout the USA (2015). In this study, due to the availability of data, only the Southern California, Northern California, and Hawaii regions, which account for 7.7 million members, were included. This patient population has been shown to be demographically and socioeconomically representative of the geographic region it covers (Karter et al. 2002, Koebnick et al. 2012).

Data sources

We used 2 data sources and linked them using the unique patient identifier assigned to each member by the healthcare system. A total joint replacement registry (TJRR) was used to identify the THA procedures and information regarding the patients, surgical indication, and surgical outcomes of these procedures. Detailed information on the registry’s coverage, processes, validation rules, and available data have been published elsewhere (Paxton et al. 2010, 2013). The integrated healthcare system’s EMR pharmacy module was the second data source for this study, identifying dispensed opioids for each THA patient. Additionally, the EMR was also used to identify specific patient characteristics and history, which were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes.

Study sample

The inclusion criteria for the study sample were: unilateral primary THA performed for osteoarthritis in adult patients (aged ≥18) without other elective arthroplasty procedures (hip or knee) within 365 days and without any history of cancer. Patients without complete 1-year follow-up (3% of cases), those with revisions for infection or any surgical site infections after their procedure, and those who had opioid amounts on the 99th percentile were considered outliers and were not included in the final sample. The final sample included 12,859 cases, where the median age was 67 years (interquartile range (IQR): 59–75) and 58% (n = 7,505) were women.

Outcomes of interest

Aseptic revision surgery within 1 and 5 years of the index procedure was the main endpoint of this study. Data on revision surgery were obtained from the TJRR, which monitors and validates all revision surgeries of primary procedures in the registry (i.e. charts are reviewed and events are confirmed by a trained clinical content expert). Revision surgery was defined as any surgery where a component from the original procedure was removed or replaced.

Exposure of interest

The cumulative daily amount—calculated as oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) (VonKorff et al. 2008)—of oral and transdermal opioid medication was calculated over 360 days after THA. The cumulative daily OME dose was calculated by summing the total dose per day based on the quantity of dispensed opioids. The total OME for a 90-day exposure time was the sum of all the daily OME doses for that period. Total post-THA OMEs per 90-day exposure period categorized into quartiles was the exposure of interest in this study. If a patient had a revision during the 360 day postoperative period, the amount of opioid exposure was calculated until the day before the revision.

Covariates/confounders

As possible confounders we evaluated sex, age at the time of surgery, opioid-related comorbidities, history of chronic pain, opioid use up to 1 year before surgery, and NSAID use 1 year before and 1 year after surgery. Opioid-related comorbidities and history of pain reported in the year before and up to THA, were defined and identified using the algorithm by Raebel et al. (2013). The opioid-related comorbidities included anxiety, bipolar disease, depression, opioid dependency, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse.

History of chronic pain was categorized into (1) non-specific chronic pain, which included general chronic pain, migraine, tension headache, abdominal pain, hernia, kidney or gall stones, menstrual pain, neuropathy, and temporo-mandibular pain; and (2) chronic musculoskeletal pain, which included back pain, neck pain, fibromyalgia, arthritis, carpal tunnel, limb-extremity pain, pain in joint, “other” chronic musculoskeletal pain, fractures and contusions, costochondritis, and intracostal muscle injury.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample and OME use. Survival analyses were used. Cox proportional regression models were used to evaluate the risk of 1- and 5-year revision and its association with the total amount of OME per 90-day postoperative period. Hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and Wald chi-square p-values are reported. Because the amount of opioid intake naturally varies over time in the post-THA rehabilitation period and in order to evaluate the independent effect of the amount of opioid during different periods of the rehabilitation period, a model for each specific postoperative 90-day exposure period was created together with 1 model for days 91–360, to evaluate the overall impact of opioids in the first year of surgery. In the first 90 days after surgery (days 1–90), the entire sample size was included in the model (n = 12,859). In the second 90-day period (days 91–180), all survivors and unrevised cases from the first period were included (n = 12,682). In the third 90-day period (days 181–270), all survivors and unrevised cases from the first and second periods were included (n = 12,568), and in the fourth period (days 271–360), all survivors and unrevised cases from the first 3 periods were included (n = 12,446).

Patients who died were treated as censored cases with survival time calculated according to the time of death. Even with death being a likely informative censoring event, we modeled the revision event as the cause-specific hazard in this study because we believe it to be a more direct estimate of treatment effectiveness. The proportional hazard assumption was checked by testing the interaction of the opioid exposure with time. The results showed that models for the first period, the third period, and the fourth period met this assumption. In the model for the second period, there was an interaction between time and OME exposure, but the overall time average effect was of interest and was therefore reported without using a time-dependent variable. 90-day OME was stratified into the following categories: no opioids (reference category), low (the lowest quartile of the total dose in that period), medium-low (between the lowest quartile and the median dose), medium-high (between the median dose and the third quartile dose), and high (those taking more than the highest quartile of opioids). All models were adjusted for age and sex, and confounders that were confirmed to be associated with revision (p < 0.10) and changed the risk estimates by at least 10%. Collinearity was assessed using tolerance values (all values >0.10), and outliers were reviewed and excluded from the sample. The alpha level chosen for statistical significance was 0.05 and the tests reported are 2-sided. SAS version 9.2 was used for all analyses.

Ethics

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB #5488) on August 27, 2009, before its commencement. No external funding was obtained for this study.

Results

In the 12,859 patients who were evaluated, the median age was 67 years (IQR: 59–75) and 58% were women (n = 7,505). In this cohort, the revision rate within 1 year was 0.9% and it was 1.7% within 5 years. The most common type of opioid-related comorbidities in the overall cohort was anxiety (9.9%), followed by depression (8.7%) and substance abuse (8.1%). Most of the patients had chronic musculoskeletal pain in the year before surgery (84%) and 11% had non-specific chronic pain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample

| Revised |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | sample | Not | revised | within | 1 year | |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Totala | 12,859 | 100 | 12,743 | 99 | 116 | 1 |

| Age, median | 67 | 67 | 68 | |||

| (IQR) | 59–75 | 59–75 | 61–75 | |||

| Men | 5,354 | 42 | 5,319 | 42 | 35 | 30 |

| Women | 7,505 | 58 | 7,424 | 58 | 81 | 70 |

| Opioid-related comorbidities | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1,268 | 9.9 | 1,246 | 9.8 | 22 | 19 |

| Bipolar | 96 | 0.8 | 95 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Depression | 1,122 | 8.7 | 1,105 | 8.7 | 17 | 15 |

| Opioid dependency | 59 | 0.5 | 57 | 0.5 | 2 | 1.7 |

| PTSD | 32 | 0.3 | 29 | 0.2 | 3 | 2.6 |

| Substance abuse | 1,041 | 8.1 | 1,021 | 8 | 20 | 17 |

| History of chronic pain | ||||||

| Chronic musculoskeletal painb, any | 10,790 | 84 | 10,690 | 84 | 100 | 86 |

| Osteoarthritis | 9,470 | 74 | 9,387 | 74 | 83 | 72 |

| Arthritis, other | 10,200 | 79 | 10,110 | 79 | 90 | 72 |

| Back pain | 2,263 | 18 | 2,236 | 18 | 27 | 23 |

| Carpal tunnel | 108 | 0.8 | 106 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.7 |

| Fibromyalgia | 124 | 1.0 | 123 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Fractures and contusions | 117 | 0.9 | 112 | 0.9 | 5 | 4.3 |

| Limb-extremity pain | 143 | 1.1 | 141 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.7 |

| Joint pain | 1,879 | 15 | 1,855 | 15 | 24 | 21 |

| Costochondritis and intra-costal muscle injury | 7 | 0.1 | 7 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Neck pain | 292 | 2.3 | 288 | 2.3 | 4 | 3.5 |

| Other chronic musculoskeletal pain | 105 | 0.8 | 104 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Non-specific chronic painc, any | 1,433 | 11 | 1,409 | 11 | 24 | 21 |

| Neurological | 697 | 5.4 | 686 | 5.4 | 11 | 9.5 |

| General chronic pain | 416 | 3.2 | 405 | 3.2 | 11 | 9.5 |

| Abdominal | 202 | 1.6 | 197 | 1.6 | 5 | 4.3 |

| Migraines | 117 | 0.9 | 116 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Dementia | 82 | 0.6 | 80 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.7 |

| Kidney/gall stones | 72 | 0.6 | 70 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.7 |

| Tension head | 55 | 0.4 | 55 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| TMD/TMJ | 31 | 0.2 | 31 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Menstrual | 6 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Preoperative 1-year opioid use | 8,091 | 63 | 8,001 | 63 | 90 | 78 |

| Preoperative 1-year NSAID use | 6,737 | 52 | 6,670 | 52 | 67 | 58 |

| Postoperative 1-year NSAID use | 5,248 | 41 | 5,201 | 41 | 47 | 41 |

IQR: interquartile range; PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; TMD/TMJ: temporo-mandibular joint disorders; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Row %, all other values are column %.

Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP): back pain, neck pain, fibromyalgia, arthritis, carpal tunnel, limb-extremity pain, pain in joint, “other” CMP, osteoarthritis, fractures and contusions, costochrondritis, and intracostal muscle injury.

Non-specific chronic pain: general chronic pain and migraines, tension headache, abdominal pain, hernia, kidney/gall stones, menstrual pain, neuropathy, temporo-mandibular.

In the first 90 days after THA, 88% of patients were dispensed opioids and the proportion of patients who took opioids and went on to be revised (90%) was similar to that in patients who did not go on to be revised (88%). Almost 1 year after surgery (days 271–360), 23% of patients were still being dispensed opioids. In the second, third, and fourth 90-day periods after surgery, the proportion of patients who were on opioids was much greater in those who went on to be revised within 1 year (Table 2) and within 5 years (data not shown).

Table 2.

Postoperative oral morphine equivalent amounts (in mg). Total, average daily use, distribution by amount quartile by time period after surgerya

| Revised |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | sample | Not | revised | within | 1 year | |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total number of casesb | 12,859 | 100 | 12,743 | 99.1 | 116 | 1 |

| Days 1–90 | ||||||

| Opioid users | 11,358 | 88 | 11,254 | 88 | 104 | 90 |

| Total amount, medianc | 200 | 200 | 306 | |||

| (IQR) | 120–400 | 120–400 | 159–561 | |||

| Average daily use (SD)c | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.2) | 6 (3.4) | |||

| 1st quartile: < 135 | 3,030 | 24 | 3,007 | 24 | 23 | 20 |

| 2nd quartile: 135–209 | 2,753 | 21 | 2,738 | 22 | 15 | 13 |

| 3rd quartile: 210–429 | 2,900 | 23 | 2,869 | 23 | 31 | 27 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 430 | 2,675 | 21 | 2,640 | 21 | 35 | 30 |

| No opioid | 1,501 | 12 | 1,489 | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| Days 91–180 | ||||||

| Opioid users | 3,461 | 27 | 3,440 | 27 | 21 | 58 |

| Total amount, medianc | 200 | 200 | 267 | |||

| (IQR) | 95–465 | 95–460 | 100–555 | |||

| Average daily use (SD)c | 5 (2.2) | 5 (2.2) | 8 (3.0) | |||

| 1st quartile: < 100 | 876 | 6.9 | 874 | 6.9 | 2 | 6 |

| 2nd quartile: 100–219 | 954 | 7.5 | 946 | 7.5 | 8 | 22 |

| 3rd quartile: 220–533 | 880 | 6.9 | 875 | 6.9 | 5 | 14 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 534 | 751 | 5.9 | 745 | 5.9 | 6 | 17 |

| No opioid | 9,221 | 73 | 9,206 | 73 | 15 | 42 |

| Days 181–270 | ||||||

| Opioid users | 3,019 | 24 | 3,004 | 24 | 15 | 65 |

| Total amount, medianc | 200 | 200 | 220 | |||

| (IQR) | 90–480 | 90–485 | 150–445 | |||

| Average daily use (SD)c | 5 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.2) | 6 (2.4) | |||

| 1st quartile: < 90 | 731 | 5.8 | 730 | 5.8 | 1 | 4 |

| 2nd quartile: 90–214 | 870 | 6.9 | 861 | 6.9 | 9 | 39 |

| 3rd quartile: 215–559 | 751 | 6.0 | 746 | 6.0 | 5 | 22 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 560 | 667 | 5.3 | 667 | 5.3 | 0 | 0 |

| No opioid | 9,549 | 76 | 9,541 | 76 | 8 | 35 |

| Days 271–360 | ||||||

| Opioid users | 2,896 | 23 | 2,889 | 23 | 7 | 88 |

| Total amount, medianc | 200 | 200 | 225 | |||

| (IQR)c | 80–510 | 80–510 | 90–423 | |||

| Average daily use (SD)c | 5 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.2) | 7 (2.5) | |||

| 1st quartile: < 85 | 736 | 5.9 | 736 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 |

| 2nd quartile: 85–209 | 782 | 6.3 | 781 | 6.3 | 1 | 13 |

| 3rd quartile: 210–579 | 741 | 6.0 | 736 | 6.0 | 5 | 63 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 580 | 637 | 5.1 | 636 | 5.1 | 1 | 13 |

| No opioid | 9,550 | 77 | 9,549 | 77 | 1 | 12 |

IQR: interquartile range.

Denominator for each time period after days 1–90 does not include the revised cases and cases lost to follow-up in the previous time period. Days 91–180, n = 12,682; days 181–270, n = 12,568; days 271–360, n = 12,446.

Row %, all other values are column %.

Median total amount and average daily use calculated for the users only; excludes patients without any opioids during that time period from denominator.

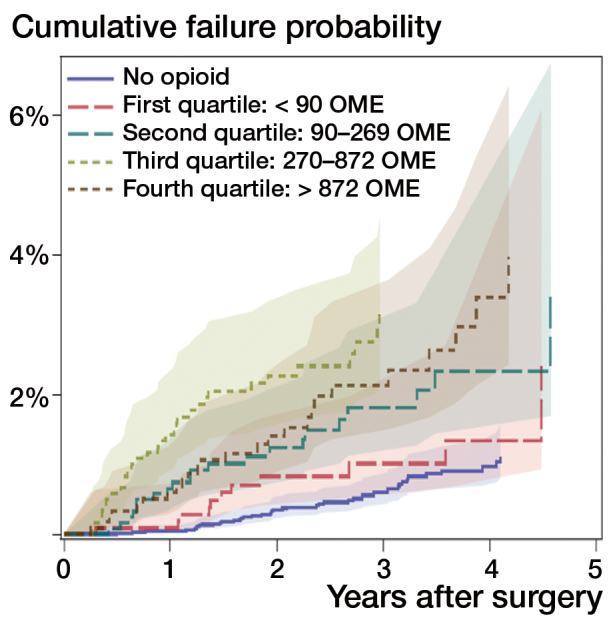

There were no differences in the adjusted risk of 1- or 5-year revision (by opioid amount) in the first 90 days after THA. When all opioid consumption in days 91–360 was evaluated, the cumulative revision probability at 1 year was higher in patients who used opioids than in those who did not use opioids. A dose-response effect was seen with higher doses of opioids, associated with higher revision risk: medium-low (90–269 mg, HR =20), medium-high (270–872 mg, HR =54), and high (≥ 873 mg, HR =43) (Figure 1 and Table 3). Consistent effects, but with lower strengths, were observed for revision within 5 years. When we evaluated specific time periods, the second 90-day period after surgery was associated with a higher adjusted risk of 1-year revision in patients with medium-low OMEs (100–219 mg, HR =6), medium-high OMEs (220–533 mg, HR =4.9), and high OMEs (≥ 534 mg, HR =11) compared to patients without any opioids. In the third 90-day period after surgery, patients with medium-low amounts of OMEs (90–214 mg, HR =17) and patients with medium-high amounts of OMEs (215–559 mg, HR =14) also had a higher adjusted risk of revision within 1 year than patients who were not on opioids. Again, there was a consistently higher risk of revision within 5 years for patients in the second and third 90-day periods after surgery, but the strengths of the effects were lower (Table 3) In the fourth 90-day period after surgery (days 271–360), estimations of 1-year risk of revision were not possible because of the small number of events. However, the 5-year adjusted risk of revision was also higher in patients taking low amounts of OMEs (< 85 mg, HR =2) and medium-high amounts of OMEs (210–579 mg, HR =3) than in patients who were not on opioids.

Figure 1.

Cumulative failure probability by oral morphine equivalent amounts (in mg) quartiles days 91–360 after surgery

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted associations of postoperative oral morphine equivalent amounts (in mg) and risk of revision by 1 year and 5 years

| 1-year revision |

5-year revision |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period OMEs (mg range)a | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Days 1–90b | ||||||

| 1st quartile: < 135 | 0.9 (0.5–2.0) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 0.9 | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.3 |

| 2nd quartile: 135–209 | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) | 0.3 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.4 |

| 3rd quartile: 210–429 | 1.3 (0.7–2.6) | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) | 0.3 | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 0.7 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 430 | 1.6 (0.9–3.0) | 1.7 (0.9–3.2) | 0.01 | 1.7 (1.0–3.0) | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) | 0.2 |

| Days 91–360c | ||||||

| 1st quartile: < 90 | 2.4 (0.3–23) | 2.6 (0.3–25) | 0.4 | 1.8 (0.8–3.7) | 1.8 (0.9–3.7) | 0.1 |

| 2nd quartile: 90–269 | 17 (4.6–64) | 20 (5.4–76) | < 0.001 | 3.0 (1.7–5.3) | 3.0 (1.7–5.2) | < 0.001 |

| 3rd quartile: 270–872 | 38 (11–130) | 54 (15–190) | < 0.001 | 4.6 (2.7–7.8) | 4.3 (2.5–7.4) | < 0.001 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 873 | 16 (3.9–63) | 43 (12–157) | < 0.001 | 3.8 (2.2–6.5) | 3.2 (1.7–6.1) | < 0.001 |

| Days 91–180c | ||||||

| 1st quartile: < 100 | 1.4 (0.3–6.1) | 1.5 (0.4–6.6) | 0.6 | 2.0 (1.1–3.5) | 2.0 (1.1–3.5) | 0.02 |

| 2nd quartile: 100–219 | 5.2 (2.2t–12) | 6.2 (2.6–15) | < 0.001 | 2.7 (1.6–4.7) | 2.7 (1.6–4.6) | < 0.001 |

| 3rd quartile: 220–533 | 3.5 (1.2–11) | 4.9 (1.8–13) | 0.002 | 2.1 (1.1–3.9) | 2.0 (1.0–3.7) | 0.05 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 534 | 4.9 (2.0–12) | 11 (2.9–44) | 0.001 | 4.0 (2.4–6.6) | 3.6 (2.1–6.1) | < 0.001 |

| Days 181–270b,d | ||||||

| 1st quartile: < 90 | 1.6 (0.2–13) | 1.8 (0.23–14) | 0.6 | 2.1 (1.0–4.6) | 2.2 (1.0–4.7) | 0.05 |

| 2nd quartile: 90–214 | 12 (4.8–32) | 17 (6.2–44) | < 0.001 | 2.6 (1.4–4.8) | 2.6 (1.4–4.8) | 0.002 |

| 3rd quartile: 215559 | 8.0 (2.6–24) | 14 (4.2–46) | < 0.001 | 2.7 (1.4–5.0) | 2.5 (1.3–4.9) | 0.005 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 560 | – | – | – | 2.7 (1.4–5.0) | 2.4 (1.3–4.6) | 0.006 |

| Days 270–360d,e | ||||||

| 1st quartile: < 85 | – | – | – | 2.1 (1.1–4.3) | 2.1 (1.1–4.3) | 0.04 |

| 2nd quartile: 85–209 | – | – | – | 1.2 (0.5–2.9) | 1.1 (0.5–2.7) | 0.8 |

| 3rd quartile: 210–579 | – | – | – | 3.4 (1.9–6.1) | 3.1 (1.7–5.5) | < 0.001 |

| 4th quartile: ≥ 580 | – | – | – | 3.0 (1.6–5.7) | 1.9 (0.9–4.4) | 0.1 |

Reference = no opioid.

1- and 5-year revision models adjusted for age and gender.

- and 5-year revision models adjusted for age, gender, and previous opioid use.

Due to insufficient events, risk estimates for days 181–270 for the 4th quartile and for the entire period of days 271–360 could not be provided.

5-year model adjusted for age and gender.

| Revision estimates | All | No opioids | 1st quartile: < 90 mg | 2nd quartile: 90–269 mg | 3rd quartile: 270–872 mg | 4th quartile: ≥ 873 mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 12,859 | 8,087 (62.9) | 1,119 (8.7) | 1,242 (9.7) | 1,218 (9.5) | 1,193 (9.3) |

| Revisions, n (%) | 213 (1.7) | 83 (1) | 23 (2.1) | 29 (2.3) | 41 (3.4) | 37 (3.1) |

| Total person years of follow-up | 34,664 | 21,792 | 3,040 | 3,365 | 3,295 | 3,172 |

| Revision rate per 100 years of follow-up | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| (95% CI) | (0.54–0.70) | (0.31–0.47) | (0.5–1.1) | (0.6–1.2) | (0.92–1.7) | (0.85–1.6) |

Discussion

In this cohort of THA patients we found that up to 1 year after surgery, 23% of patients were dispensed opioids. Persistent pain after THA is consistent with findings from studies using PROMs where it was found that 4 years after THA, almost a third of patients reported having little to no improvement in pain and function, based on the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis (WOMAC) scores (Nilsdotter et al. 2003). Moderate to severe pain was reported in 11% of patients 5 years after THA, using patient questionnaires (Singh and Lewallen 2010), and chronic pain was reported in 12% of patients 12–18 months after THA in a nationwide Danish study where participants were mailed self-reported questionnaires (Nikolajsen et al. 2006). A systematic review of prospective studies identified an unfavorable degree of long-term pain in 7–23% of THA patients (Beswick et al. 2012).

Few studies have looked at the prevalence of prolonged opioid use after THA. One study found that 3% of patients continued to use opioids 2 years after THA, but relied on patient self-reporting for medication information (Singh and Lewallen 2010). Patient-reported information can have response bias, and in that study a response rate of 62% was reported. In the present study, 23% of patients continued to use opioids 9–12 months after THA. While this rate may seem high, it may reflect the actual contemporary opioid prescription practices in the USA (Manchikanti et al. 2012). Our numbers are in agreement with those from a study in the UK, where 25% of patients were still taking opioids 5 years after total joint replacement surgery (Valdes et al. 2015). The pharmacy data in the integrated healthcare system used for our investigation provide an accurate account of opioid prescriptions dispensed to a patient. Self-reported use of narcotics by patients may be affected by poor response rates, and by the fact that patients may not be aware that the medications they are taking are, in fact, opioids. Surgeons may not realize that their patients are receiving opioid prescriptions from other healthcare providers.

Revision surgery is a definitive outcome for the evaluation of THA procedures, but it is limited by being a late and low-frequency event. Another shortcoming is that some patients may have a poor outcome, but not decide to undergo a reoperation. There is a practical need for earlier assessment of THA outcomes. Since the collection of patient-reported outcomes can be burdened by cost, variable response rates, and time- and labor-intensiveness, we investigated using the amount of opioid used to treat postoperative pain as a possible new indicator of early failure. We found that continued use of 100 mg OME per 90-day period increased the risk of revision THA after the initial 90-day postoperative period. Low-dose opioid use, however, was not associated with risk of 1-year revision. From 9 months to 12 months after THA, 23% of patients who were not revised were taking opioids. In the same time period, 88% of patients who underwent revision surgery were taking opioids before their revision. When the second, third, and fourth postoperative quartiles were combined as one time period (days 91–365), there was a dose-response association with higher doses of opioids and higher 1-year revision risk. Prescriptions of 210–579mg OME in the 9- to 12-month postoperative period resulted in a 3-fold risk of revision at 5 years. The higher risk was independent of age, sex, previous analgesic use, opioid-related comorbidities, and chronic pain diagnoses.

The limitations of our study include the fact that having opioid prescriptions at hand does not necessarily mean that the patients actually ingested the medication. Compliance and adherence are difficult to measure in observational studies such as this. It is also possible that opioids could have been used for other pain conditions instead of the affected hip joint. We tried to remove some of the effect introduced by this possibility by adjusting all of our analyses for other types of chronic pain and specific comorbidities the patient had that could be associated with higher opioid consumption, and by not including patients with more than 1 joint replacement procedure within a year. However, it is still possible that some residual confounding—by variables not included in our analysis—existed and affected our estimations. It is also possible that certain patients who have a painful THA choose to use means of dealing with pain other than taking narcotics. However, this would only affect our estimations towards the null effect, so our statements of risk of revision are probably conservative. We did not include the competing risk of death, which may have led to overestimations of our risk estimates. Due to a lack of sufficient events with each type of revision, we were unable to determine whether opioid exposure was associated with certain types of THA failures. Our data are also observational, and therefore only associations between opioid use and revision surgery are reported; no causality can be inferred.

The strengths of our study include the use of a data source (to ascertain medication use) that has a low risk of bias, the inclusion of a large number of patients from a dedicated TJRR with rich, prospectively collected, clinical information on the patients, and the generalizability of the patients, surgeons, and hospitals included in the study. Using medication prescription dispensing information to ascertain opioid use (instead of patient-reported use) allows more accurate and complete ascertainment of this information. Because the information collected by the Kaiser Permanente TJRR is predefined and prospectively collected, there is high internal validity of the data collected. Another strength of our study is the accuracy of database linking, since the healthcare system uses a unique patient identifier. The sampling frame of this study has been shown to be largely representative of the population of the geographical area it covers, ensuring that the findings are generalizable to a larger population (Karter et al. 2002, Koebnick 2012). Finally, a wide range of surgeons and hospitals (with respect to volume, experience, and settings) contributed cases to the cohort of patients analyzed in this study, and this was also representative of the larger surgical orthopedic community in the USA (Katz et al. 2001).

In conclusion, the prolonged use of low to medium and higher doses of opioids after the initial 90-day postoperative period may identify patients who are at risk of requiring revision surgery. These patients should be closely monitored.

References

- Alviar M J, Olver J, Brand C, Tropea J, Hale T, Pirpiris M, Khan F.. Do patient-reported outcome measures in hip and knee arthroplasty rehabilitation have robust measurement attributes? A systematic review. J Rehabil Med 2011; 43 (7): 572–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beswick A D, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P.. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012; 2 (1): e000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013; (Jan 28): 346:f167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Permanente Fast Facts about Kaiser Permanente. Available from http://share.kaiserpermanente.org/artcile/fast-facts-about-kaiser-permanente/. Fast Facts about Kaiser Permanente. Available from http://share.kaiserpermanente.org/artcile/fast-facts-about-kaiser-permanente/. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karter A J, Ferrara A, Liu J Y, Moffet H H, Ackerson L M, Selby J V.. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA 2002; 287 (19): 2519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J N, Losina E, Barrett J, Phillips C B, Mahomed N N, Lew R A, Guadagnoli E, Harris W H, Poss R, Baron J A.. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and outcomes of total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A (11): 1622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebnick C, Langer-Gould A M, Gould M K, Chao C R, Iyer R L, Smith N, Chen W, Jacobsen S J.. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau Data. Perm J 2012; 16 (3): 37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti L, Helm S 2nd, Fellows B, Janata J W, Pampati V, Grider J S, Boswell M V.. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician 2012; 15 (3 Suppl): ES9–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolajsen L, Brandsborg B, Lucht U, Jensen T S, Kehlet H.. Chronic pain following total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide questionnaire study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2006; 50 (4): 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsdotter A-K, Petersson I F, Roos E M, Lohmander L S.. Predictors of patient relevant outcome after total hip replacement for osteoarthritis: a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62 (10): 923–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E W, Inacio M C, Khatod M, Yue E J, Namba R S.. Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry: aligning operations with information technology. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (10): 2646–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E W, Kiley M L, Love R, Barber T C, Funahashi T T, Inacio M C.. Kaiser Permanente implant registries benefit patient safety, quality improvement, cost-effectiveness. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2013; 39 (6): 246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raebel M A, Newcomer S R, Reifler L M, Boudreau D, Elliott T E, DeBar L, Ahmed A, Pawloski P A, Fisher D, Donahoo W T, Bayliss E A.. Chronic use of opioid medications before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA 2013; 310 (13): 1369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranawat A S, Ranawat C S.. Pain management and accelerated rehabilitation for total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22 (7 Suppl 3): 12–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell A G, Hooper G J, Hobbs A, Frampton C M.. An analysis of the Oxford hip and knee scores and their relationship to early joint revision in the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92 (3): 413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J A, Lewallen D.. Predictors of pain and use of pain medications following primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA): 5,707 THAs at 2-years and 3,289 THAs at 5-years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes A M, Warner S C, Harvey H L, Fernandes G S, Doherty S, Jenkins W, Wheeler M, Doherty M.. Use of prescription analgesic medication and pain catastrophizing after total joint replacement surgery. Sem Arth Rheum 2015; (45): 150–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendittoli P A, Makinen P, Drolet P, Lavigne M, Fallaha M, Guertin M C, Varin F.. A multimodal analgesia protocol for total knee arthroplasty. A randomized, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 (2): 282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VonKorff M, Saunders K, Thomas Ray G, Boudreau D, Campbell C, Merrill J, Sullivan M D, Rutter C M, Silverberg M J, Banta-Green C, Weisner C.. De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain 2008; 24 (6): 521–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]