Abstract

Although the photosynthetic reaction center is well conserved among different cyanobacterial species, the modes of metabolism, e.g. respiratory, nitrogen and carbon metabolism and their mutual interaction, are quite diverse. To explore such uniformity and diversity among cyanobacteria, here we compare the influence of the light environment on the condition of photosynthetic electron transport through Chl fluorescence measurement of six cyanobacterial species grown under the same photon flux densities and at the same temperature. In the dark or under weak light, up to growth light, a large difference in the plastoquinone (PQ) redox condition was observed among different cyanobacterial species. The observed difference indicates that the degree of interaction between respiratory electron transfer and photosynthetic electron transfer differs among different cyanobacterial species. The variation could not be ascribed to the phylogenetic differences but possibly to the light environment of the original habitat. On the other hand, changes in the redox condition of PQ were essentially identical among different species at photon flux densities higher than the growth light. We further analyzed the response to high light by using a typical energy allocation model and found that ‘non-regulated’ thermal dissipation was increased under high-light conditions in all cyanobacterial species tested. We assume that such ‘non-regulated’ thermal dissipation may be an important ‘regulatory’ mechanism in the acclimation of cyanobacterial cells to high-light conditions.

Keywords: Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements, Cyanobacteria, Photochemical quenching, Respiration, State transition, Thermal dissipation

Introduction

Cyanobacteria are the first life form performing oxygenic photosynthesis and are the evolutionary origin of the chloroplast in plants. Although the photosynthetic machinery of photosynthetic reaction center complexes is almost identical between cyanobacteria and chloroplasts, metabolic interaction of photosynthesis with other cellular processes is fundamentally different. As a photosynthetic prokaryote, cyanobacteria do not have organelles and all the metabolic pathways could directly interact with one another. In particular, photosynthetic electron transport and respiratory electron transport shared several electron transfer components such as plastoquinone (PQ), the Cyt b6/f complex and Cyt c (Aoki and Katoh 1982, Peschek and Schmetterer 1982). This direct interaction between photosynthesis and respiration makes cyanobacterial photosynthesis different from photosynthesis of land plants. In the case of land plants, the PQ pool is oxidized in the dark, and gradually reduced along with the elevation in photon flux densities (PFDs). In the case of cyanobacteria, however, the PQ pool is already reduced in the dark due to respiratory electron transfer (Mullineaux and Allen 1986, Schreiber et al. 1995, Campbell and Öquist 1996). Low light illumination oxidizes, not reduces, the PQ pool in the case of cyanobacteria (Campbell and Öquist 1996, Campbell et al. 1998). A further increase in the PFD reduces the PQ pool again.

The PQ pool is one of the regulatory sites of photosynthetic electron transfer and energy dissipation. The redox state of the PQ pool or neighboring electron carriers is known to regulate state transition both in land plants and in cyanobacteria. Light energy absorbed by the PSII antenna complex may be directed either to the PSII reaction center complex or to the PSI reaction center complex, depending on the redox state of the PQ pool during the process of state transitions, both in land plants and in cyanobacteria. There are at least two different mechanisms in cyanobacterial state transition. In low-light-acclimated cells of cyanobacteria, the RpaC-dependent state transition is induced to maximize the efficiency of photosynthesis (Emlyn-Jones et al. 1999). On the other hand, the PsaK2-dependent state transition is induced to avoid photoinhibitory damage in high-light-acclimated cells (Fujimori et al. 2005). State transition seems to have a protective role in addition to a regulatory role in land plants too (Bellafiore et al. 2005).

Since redirection of light energy to PSI decreases the yield of fluorescence from PSII, the state transition could be viewed as the quenching of Chl fluorescence. The origin of such quenching is also different between land plants and cyanobacteria. In the case of land plants, the most conspicuous non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) is energy-dependent quenching (qE) due to the xanthophyll cycle, which plays an important protective role in avoiding photoinhibitory damage (Demmig-Adams and Adams 1996). qE could be distinguished from the quenching due to state transition (qT) or that due to photoinhibition (qI) by the rate of recovery from quenching in the dark (Quick and Stitt 1989, Krause and Weis 1991). The situation is somewhat different in algae, which have a very diverse antenna system for photosynthesis. Different algal group might have different mechanisms of qE (Goss and Lepetit 2015). Even within one class of green algae (e.g. Trebouxiophyceae or Chlorophyceae), the existence of the different mechanisms in qE among species has been implied (Quaas et al. 2015).

On the other hand, the mechanism of cyanobacterial NPQ is totally different from that of land plants and algae. Cyanobacteria do not have a xanthophyll cycle (Stransky and Hager 1970) and NPQ is mainly ascribed to state transition (Campbell and Öquist 1996). Under strong blue light conditions, orange carotenoid protein (OCP) could dissipate excess energy in the phycobilisome antenna to protect the machinery of the photosystem (Kirilovsky 2007). However, the division of roles between state transition and OCP in protection from photoinhibitory damage has not been examined.

Although the photosynthetic reaction center is well conserved among different cyanobacterial species, the modes of metabolism and their mutual interaction are quite diverse. There are few studies comparing the interaction of photosynthesis and other metabolic pathways or light energy dissipation among different species of cyanobacteria grown under certain conditions. Here we examined the effect of respiration of photosynthetic electron transfer and energy dissipation in six cyanobacterial species using Chl fluorescence measurements. We found that the redox state of the PQ pool in the dark is totally different among different cyanobacterial species. Furthermore, the correlation between the redox state of PQ and the yield of energy dissipation in the dark to the growth light range is different from that in growth light to the high light range. Apparently, some process of energy dissipation was induced only under high-light conditions. The results obtained here demonstrate species differences in the redox state and species commonality in energy dissipation in cyanobacteria.

Results

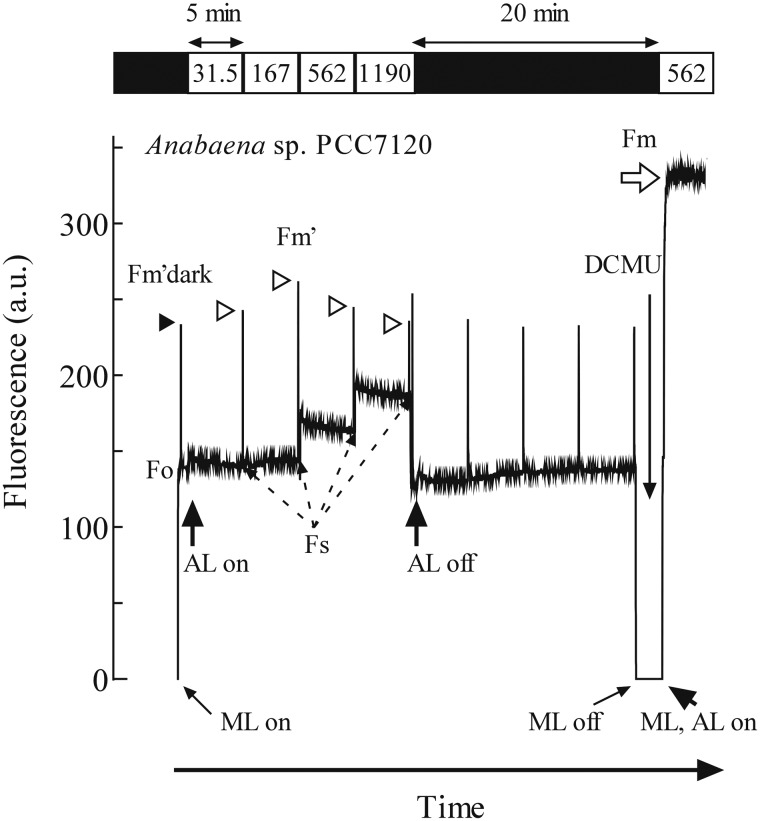

Since photosynthetic electron transport and respiratory electron transport in cyanobacteria share several components such as PQ (Aoki and Katoh 1982, Peschek and Schmetterer 1982), the PQ pool is not oxidized in the dark due to electron flow from respiratory NADPH dehydrogenase (NDH) complexes to the PQ pool (Mi et al. 1992, Mi et al. 1994, Ogawa et al. 2013). The reduced PQ pool brings cyanobacterial cells into State 2 in the dark, decreasing fluorescence yield. This decrease of fluorescence yield is clearly observed in Fig. 1, in which the result of quenching analysis of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 is shown. The level of maximum fluorescence of the dark-acclimated cells upon a saturating pulse (Fig. 1, closed arrowhead), designated as Fm′dark here, was low, compared with the Fm value (open arrow) obtained with illumination in the presence of DCMU, which locked the cells into State 1. When the PFD of the actinic light was raised in a stepwise manner (31.5, 167, 562 and 1,190 µmol m−2 s−1), the maximum fluorescence level (Fm′, open arrowheads) increased once at around the growth light PFD (200 µmol m−2 s−1), and decreased again under higher PFD (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Quenching analysis of the fluorescence kinetics of Anabaena sp. cells grown at 30°C and bubbled with air under continuous illumination at 200 µmol m−2 s−1 for 24 h. The measurement was initiated by applying a modulated measuring light (ML on) after 15 min dark acclimation of the cells. Shortly after the start of the measurement, a 0.8 s pulse of saturating light was applied to close PSII temporarily for the determination of Fm′dark. After actinic light was turned on (AL on), the level of fluorescence changed slightly and then settled down to the steady state (Fs) during 5 min under each PFD. At the end of each 5 min period, saturating pulses were given to determine Fm′ at the respective actinic light. The actinic light was then turned off (AL off), and saturating light was applied every 5 min to observe the recovery kinetics of Fm′ in the absence of actinic light. Finally, DCMU was added in the presence of actinic light to bring cells fully to State 1 for the determination of Fm. The black bar indicates the absence of actinic light. Each number in the white bar indicates the respective PFDs of actinic light (µmol m−2 s−1).

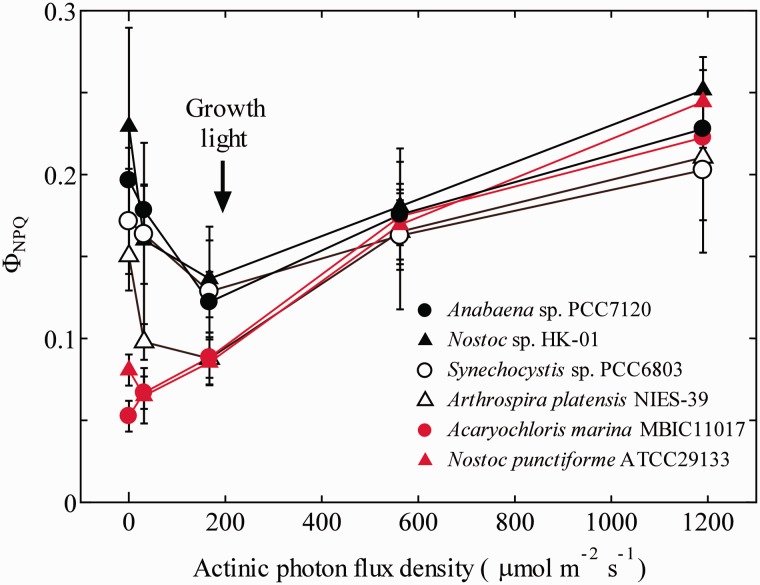

This change in the levels of Fm′ reflects the change in the NPQ of Chl fluorescence. ΦNPQ, a parameter which represents non-photochemical quenching by regulated thermal dissipation, was high in the dark in the case of Anabaena sp. but decreased around the growth light PFD and increased again under higher PFD, giving a concave dependence on actinic PFD (Fig. 2, filled circles; see also Campbell and Öquist 1996). Very similar tendencies were observed in Nostoc sp. HK-01 (filled triangles) and Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 (open circles). Arthrospira platensis NIES-39 (open triangles) also showed a more or less similar tendency, but Nostoc punctiforme ATCC29133 (red circles) and Acaryochloris marina MBIC11017 (red triangles) showed a rather linear dependence starting at a low NPQ in the dark (i.e. no actinic light). Apparently, the levels of NPQ under high actinic PFD are similar among cyanobacterial species, while those under low PFD are variable depending on the species.

Fig. 2.

Actinic light dependence of ΦNPQ of the six cyanobacterial species. Mean values of at least three independent measurements and their respective SD are presented.

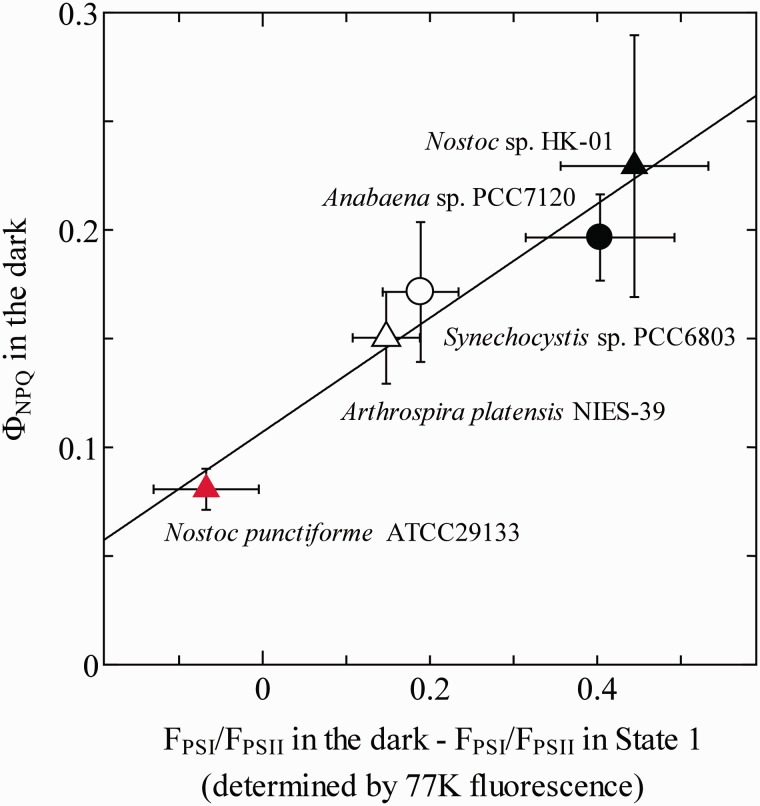

Cyanobacterial NPQ is ascribed either to state transition (Mullineaux and Allen 1990, Campbell and Öquist 1996) or to thermal dissipation by OCP (Kirilovsky 2007). Since red light from a light-emitting diode (LED; peak at 660 nm) was used here for actinic light, it is not necessary to take the involvement of OCP into consideration. To explore the relationship between state transition and NPQ in the dark, the index of State 2 in the dark was estimated from the relative peak height of the Chl fluorescence spectra determined at 77 K. ΦNPQ in the dark showed a linear correlation with the index of State 2 in the dark among five cyanobacterial species (Fig. 3). A. marina was omitted from this figure, since the presence of Chl d in this organism makes the comparison with other species difficult. The result obtained here indicates that the difference in the state transition is the cause of the variation in NPQ among the species. That, in turn, suggests that the redox condition of the PQ pool in the dark is different among the cyanobacterial species.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between the ΦNPQ in the dark and the state transition. The degree of state transition was estimated as the difference in the ratio of PSI fluorescence and PSII fluorescence determined at 77 K between the dark-acclimated condition and the State 1-induced condition. Mean values of at least three independent measurements and their respective SD are presented. The line in the figure represents the linear fitting result (R2 = 0.95).

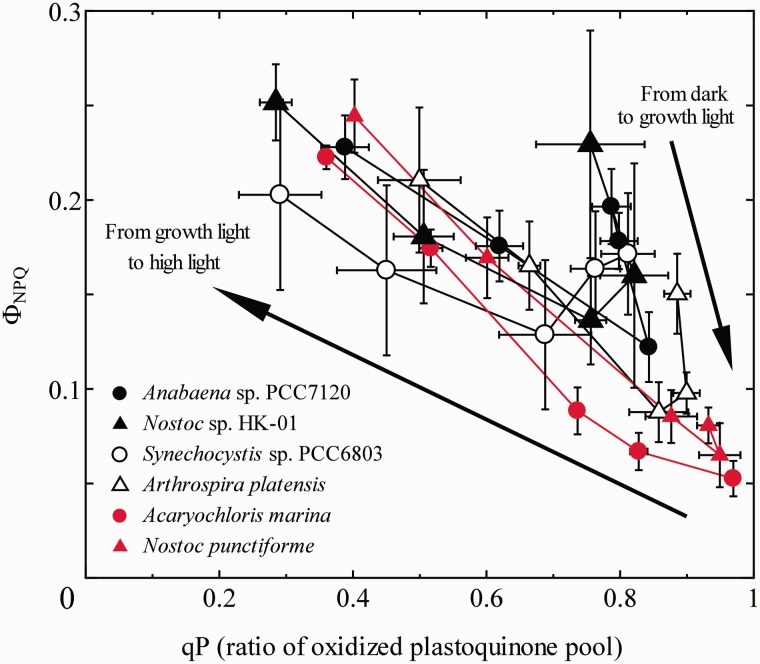

We next examined the relationship between the ΦNPQ and qP, another parameter representing the redox state of the PQ pool, during the course of increasing actinic light in six cyanobacterial species to examine the resulting change in ΦNPQ (Fig. 4). Apparently, the overall relationship was not linear in Anabaena sp. (filled circles), Nostoc sp. HK-01 (filled triangles) and A. platensis NIES-39 (open triangles). From darkness to the growth light condition, the increase of qP (i.e. oxidation of the PQ pool) accompanied the decrease of ΦNPQ (i.e. transition to State 1) in these three cyanobacterial species. From growth light to the high-light condition, however, qP decreased again accompanying the increase of the ΦNPQ but with a different slope. As a result, the overall relationship showed a V-shape consisting of two lines with different slopes. In the case of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, the increase in qP was not apparent (open circles). As for the other two cyanobacterial species, i.e. N. punctiforme ATCC29133 (red circles) and A. marina MBIC11017 (red triangles), the data point obtained in the dark is already near the bottom of the V-shape, and the monotonic increase of ΦNPQ accompanied the decrease of qP, representing only a half of the V-shape. It must be noted, however, that the data points of all the six cyanobacterial species were located more or less on the same letter V. Since cyanobacterial ΦNPQ is mainly attributed to state transition that is induced by the reduction of the PQ pool, the result indicates that the mechanism of the change in ΦNPQ is different between from darkness to growth light conditions and from growth light to high-light conditions. Thus, the qP–ΦNPQ plot in Fig. 4 clearly indicates that the increase of ΦNPQ under high light is not the simple reversal of the decrease of ΦNPQ by the growth light illumination.

Fig. 4.

The relationship between ΦNPQ and the ratio of the oxidized PQ pool (qP). Mean values of at least three independent measurements and their respective SD are presented.

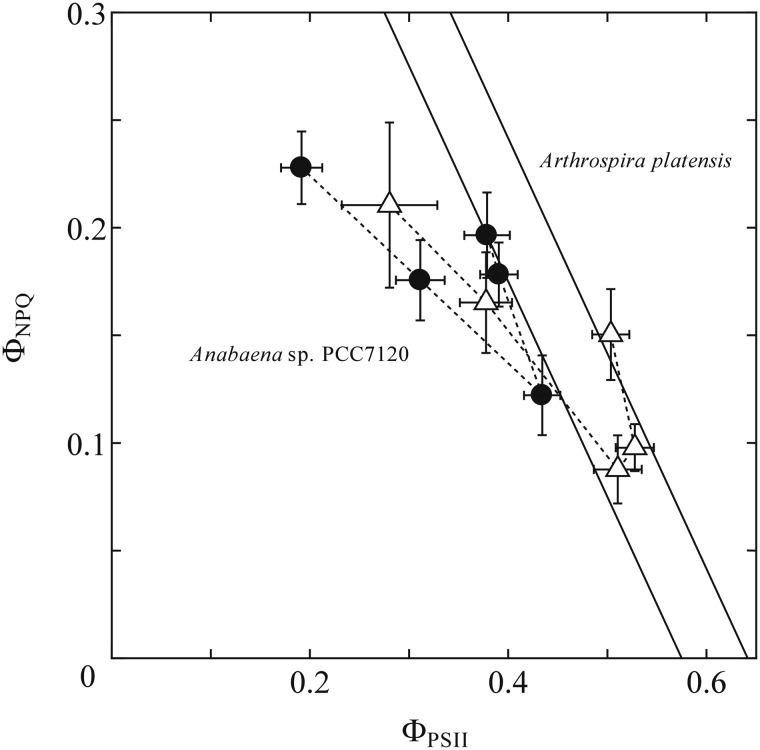

We selected two cyanobacterial species that showed the typical V-shape pattern in Fig. 4 for further analysis, and examined the relationship between ΦNPQ and ΦPSII, a parameter representing the quantum yield of electron transfer through PSII (Fig. 5). Together with Φf, D, a parameter representing non-regulated thermal dissipation, allocation of the absorbed energy could be analyzed here, since the sum of ΦNPQ, ΦPSII and Φf, D is unity. Both Anabaena sp. PCC7120 (Fig. 5, filled circles) and A. platensis NIES-39 (Fig. 5, open triangles) showed a clear V-shape pattern. However, they are not on the same letter V but rather are slightly shifted relative to one another. Two straight lines in Fig. 5 are drawn under the condition where the sum of ΦNPQ and ΦPSII is constant (i.e. Φf, D is constant) and passing the respective co-ordinate (ΦNPQ = 0, ΦPSII = Fv/Fm) for the respective cyanobacterial species. Apparently, the change in the first half of the V-shape pattern, i.e. the change from the dark-acclimated state to the growth light condition, fitted well to the lines of the Φf, D constant, and the shift of the letter V was well explained by the difference in Fv/Fm between Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 and A. platensis NIES-39 (Table 1). Two lines of ΦNPQ + ΦPSII = Fv/Fm, i.e. ΦNPQ + ΦPSII = 0.575 for Anabaena sp. PCC7120 and ΦNPQ + ΦPSII = 0.642 for A. platensis NIES-39, represent the data points well. Thus, this part of the lines could be explained by the oxidation of the PQ pool that, in turn, triggers the state transition without any change in non-regulated heat dissipation. On the other hand, the change in the second half of the V-shape pattern, i.e. the change from growth light to high light, showed a different slope and could not be explained by the lines of the Φf, D constant.

Fig. 5.

The relationship between ΦNPQ and ΦPSII in Anabaena sp. PCC7120 (filled circles) and Arthrospira platensis NIES-39 (open triangle). Mean values of at least three independent measurements and their respective SD are presented. Two black solid lines represent the relationship of ΦNPQ + ΦPSII = Fv/Fm, in which experimentally determined Fv/Fm values of respective species were used, i.e. ΦNPQ +ΦPSII = 0.575 for Anabaena sp. PCC7120 and ΦNPQ + ΦPSII = 0.642 for Arthrospira platensis NIES-39. The dashed lines just connect data points to show the course of the increase in actinic PFD.

Table 1.

Photosynthetic parameters and the PC/Chl ratio of the six cyanobacterial species

| Species | Fv/Fm | (Fm′dark – Fo)/Fm′dark | PC/Chl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acaryochloris marina | 0.669 ± 0.029 | 0.617 ± 0.035 | – |

| Arthrospira platensis | 0.642 ± 0.017 | 0.503 ± 0.019 | 4.33 ± 0.04 |

| Nostoc sp. | 0.599 ± 0.010 | 0.369 ± 0.054 | 4.80 ± 0.27 |

| Nostoc punctiforme | 0.591 ± 0.030 | 0.510 ± 0.039 | 5.76 ± 0.12 |

| Anabaena sp. | 0.575 ± 0.009 | 0.379 ± 0.023 | 6.72 ± 0.46 |

| Synechocystis sp. | 0.561 ± 0.022 | 0.389 ± 0.035 | 8.03 ± 0.64 |

Values represent the average ± SD with at least three independent cultures.

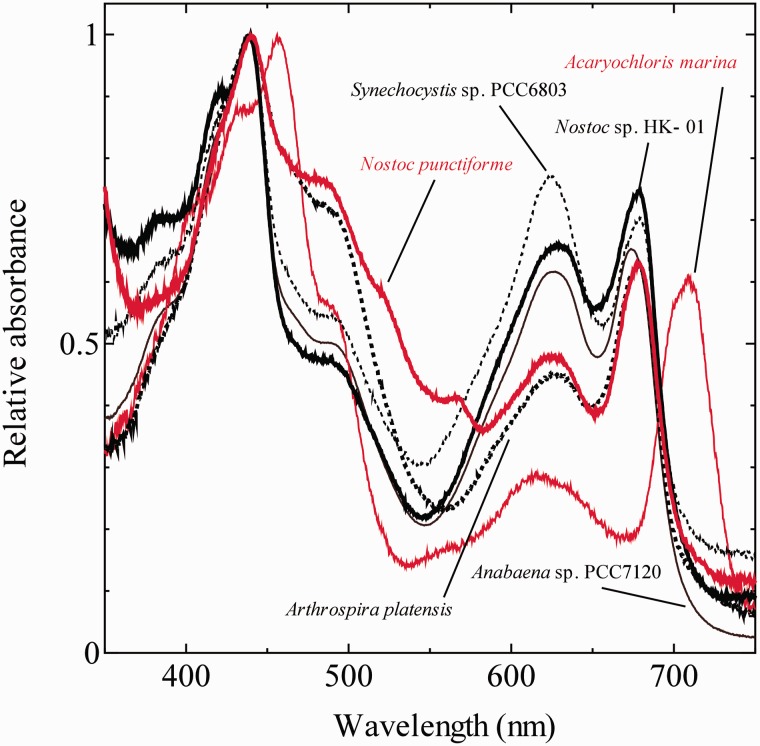

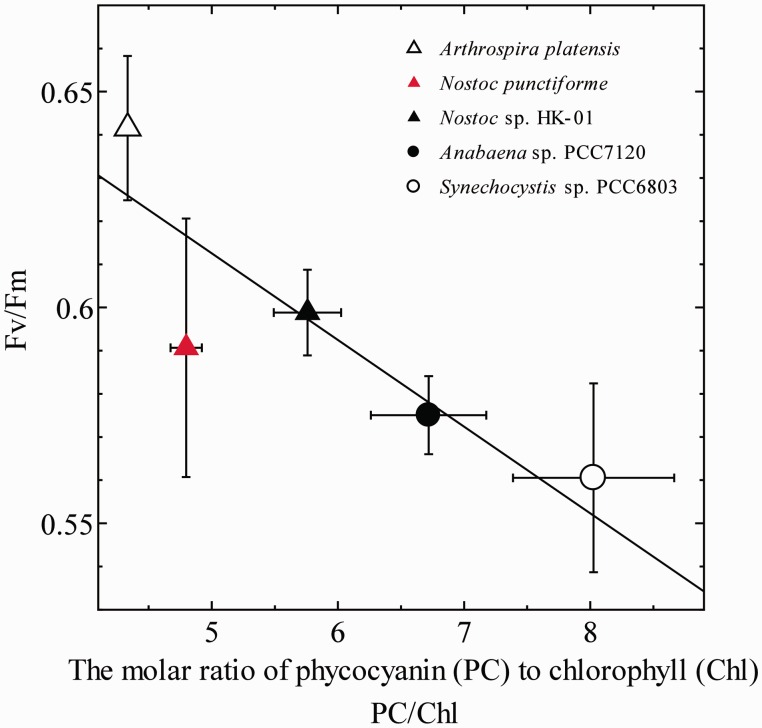

Finally, the cause of the difference in Fv/Fm among cyanobacterial species was examined. Fv/Fm values showed some variation dependent on the cyanobacterial species (Table 1). Although the value (Fm′dark – Fo)/Fm′dark, was greatly affected by the degree of state transition, Fv/Fm values determined in the presence of DCMU were not affected by the state transition (Table 1), since the cells were locked in State 1 in the presence of DCMU. Fv/Fm is well known to be a parameter representing the maximum quantum yield of PSII but was reported to be affected by the cellular content of phycobiline (Campbell et al. 1998). We determined the absorbance spectra of intact cells (Fig. 6) to calculate the phycocyanin (PC)/Chl ratio for the six cyanobacterial species. When the correlation between Fv/Fm and the PC/Chl ratio was plotted, a negative correlation was observed (Fig. 7), suggesting the variation of the PC content as the cause of the difference in Fv/Fm. In other words, although the six cyanobacteria were grown at the same temperature and the same PFD, the pigment composition ratio was different among the species and the variation in the pigment composition among the species caused the species difference of Fv/Fm.

Fig. 6.

Absorption spectra of the intact cells of six cyanobacterial species in the growth medium. Each absorption spectrum was normalized at the peak height of the respective highest peak. Averages of spectra with three independent cultures are presented.

Fig. 7.

The relationship between Fv/Fm and the phycocyanin content. Mean values of at least three independent measurements and their respective SD are presented.

Discussion

Cyanobacterial diversity observed in the PQ reduction in the dark

It is well known that the PQ pool is mostly reduced in dark-acclimated cells of cyanobacteria (Campbell et al. 1998), which is quite different from the case of land plants. Apparently, such a dark reduction of the PQ pool is not observed in all cyanobacterial species. Among the six cyanobacterial species examined in this study, the PQ pool was reduced to different extents in four species but it is oxidized in the dark-acclimated cells of N. punctiforme ATCC29133 and A. marina MBIC11017. All the cells are grown at the same temperature and under the same PFD, so the difference among species could not be ascribed to the difference in growth conditions, but to the intrinsic nature of the cyanobacterial species.

Since the two Nostoc species, Nostoc punctiforme ATCC29133 and Nostoc sp. HK-01, showed totally different redox conditions of their PQ pool in the dark, the diversity could not be explained solely by phylogenetic factors. Nostoc punctiforme ATCC29133 was first isolated as a symbiont from a root of a gymnosperm cycad in Australia (Rippka and Herdman 1992). A. marina MBIC11017, another cyanobacterium with an oxidized PQ pool in the dark, was also originally isolated from inside of an ascidian in Palau (Miyashita et al. 1996). The light environments of the original habitats of these cyanobacteria should be rather weak, and adaptation to such environments may be the evolutionary cause of the PQ pool characteristics. The life style as a symbiont may be also considered as the cause of PQ oxidation in the dark, but it is difficult to assume such a concrete connection between them.

As for the actual mechanism of the variation in the redox condition of the PQ pool, there are three possibilities: first, the redox state of the cytosol may affect the condition of the PQ pool. For example, Mi et al. (1994) showed that dark-starved cells of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 had an oxidized PQ pool that might have resulted from starvation of the respiratory substrates in the cytosol. In our experiments, however, the cells were grown photoautotrophically under continuous light so that the concentration of respiratory substrates should not be particularly different among species. Secondly, the difference in the activities of the NDH complex upstream of the PQ pool may result in the variation in the PQ redox. Since the inactivation of the NDH complex resulted in the oxidation of the PQ pool (Ogawa et al. 2013), the difference in the activity of the NDH complex would be a plausible candidate for the cause of the species difference of PQ redox. Thirdly, the difference in Cyt c oxidase (COX) activity in the dark may contribute to the variation in PQ redox. It was reported that Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 could grow heterotrophically in the dark when a mutation was introduced in the Cyt cM gene (Hiraide et al. 2014). It was implied that Cyt cM would act as a negative regulator for COX activity in cyanobacteria lacking the ability to grow heterotrophically in the dark. In cyanobacteria with the ability to grow heterotrophically in the dark, e.g. N. punctiforme, COX activity would be kept relatively high in the dark, resulting in the oxidation of the PQ pool in the dark. The actual mechanism, however, should be tested in the near future.

Regulatory energy dissipation is not limited to NPQ in cyanobacteria

As discussed above, the PQ pool is in a reduced condition which could be monitored as a low qP level in the dark-acclimated cyanobacterial cells, and the PQ reduction induced the State 2 condition which could be monitored as high ΦNPQ. Upon the increase of actinic illumination, the PQ pool is gradually oxidized (i.e. qP is gradually increased), inducing transition to State 1 that could be monitored as the decrease in ΦNPQ. Until the actinic light reached the growth light level, the relationship between qP and ΦNPQ is linear, suggesting that this process is a simple state transition to State 1 induced by the oxidation of the PQ pool. No other energy dissipation process was induced under the growth condition, since Φf, D was constant during this process. Although the initial levels of the PQ redox state in the dark varied among cyanobacterial species, the qP–ΦNPQ relationships and ΦPSII–ΦNPQ relationships were more or less similar, with the same slope between the dark condition and growth light condition. In this sense, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is somewhat peculiar, showing a decrease in ΦNPQ in the dark to growth light transition without apparent PQ oxidation. A similar change was observed by Campbell et al. (1998), but the mechanism of this change is unknown. Apparently, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is not a typical cyanobacterium from the view of the relationship between PQ redox and state transition.

The reverse change was observed in the range from the growth light to high light, i.e. the level of qP decreased while the level of ΦNPQ increased again. Although the change in this range could be partly attributed to the reverse transition to State 2 induced by the reduction of the PQ pool, the slope of the qP–ΦNPQ relationships (or ΦPSII–ΦNPQ relationships) was different from that in the range from the dark condition to the growth light condition. The relationship between ΦPSII and ΦNPQ indicates that Φf, D was increased by high light together with the state transition induced by the reduction of the PQ pool. In many land plant species, the level of Φf, D was reported to be relatively constant with a wide range of actinic PFD, and thus Φf, D was regarded as ‘non-regulatory’ energy dissipation as fluorescence or as heat (Hendrickson et al. 2004, Zhang et al. 2011, Park 2013). In cyanobacteria, however, an increase of Φf, D was observed in all the species tested here, and the rates of the increase of Φf, D (i.e. the slopes of the data lines in the ΦPSII–ΦNPQ relationships) were similar among species. Hendrickson et al. (2004) showed that Φf, D in Vitis vinifera increased along with the increase of actinic light to 500 µmol m−2 s−1 at 25°C, but not at 10°C. Since Φf, D decreased, not increased, in the higher actinic light range (750–2,000 µmol m−2 s−1) in their experiments, the mechanism of Φf, D regulation in land plants would be different from the one in the cyanobacteria observed here. Judging from the full recovery of Fm′ in the dark within 5–10 min (Fig. 1), significant photoinhibition was not induced by high light, which could be the cause of the apparent increase in Φf, D. Furthermore, no persistent photoinhibition under the growth condition was induced, since the change in Fv/Fm was mostly explained by the change in PC contents. Thus, photoinhibition is not the cause of the increase in Φf, D.

It was reported that a passive increase of Φf, D under high light was observed in the M55 mutant of NDH-1 complexes, which is incapable of state transition (Schreiber et al. 1995). Similarly, an increase in Φf, D was observed in the PsbS mutant of rice plants, which is deficient in some mechanism of NPQ (Ishida et al. 2011, Ikeuchi et al. 2014). These results may suggest that the increase in Φf, D is induced in the absence of physiological energy dissipation. Since red actinic light was used in our study, OCP was not induced in our experimental conditions. Furthermore, the increase of Φf, D was reported under strong blue light in the OCP deletion mutant of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, resulting in the decrease of ϕNPQ but not in the change of ΦPSII (Kusama et al. 2015). In our preliminary result, however, the V-shape relationship between ΦPSII and ΦNPQ was observed even when blue light was employed as actinic light. Unfortunately, blue light also acts as PSI light, resulting in oxidation of the PQ pool that complicated the interpretation of the results. The involvement of the OCP in the change of Φf, D should be further explored in the near future. It should also be noted that we employed rather a high PFD (200 µmol m−2 s−1) for the growth light. It was reported that there are at least two types of state transition in cyanobacteria. PsaK2-dependent state transition was only induced in high-light-acclimated cells (Fujimori et al. 2005), while RpaC-dependent state transition is functional under low-light conditions (Emlyn-Jones et al. 1999). The lack of the RpaC-dependent state transition in high-light-acclimated cells may also bring about the increase of Φf, D in the absence of physiological energy dissipation.

In any event, the mechanism of the induction of Φf, D could not be ascribed solely to a passive increase, since the increase in Φf, D was observed in the actinic light range where the induction of NPQ was not saturated. The increase of Φf, D should lead to smaller energy allocation to photosynthetic electron transfer. Similarly to the case of NPQ, the induction of Φf, D that has been defined as ‘non-regulatory’ in the past may also contribute to the protection of the photosynthetic machinery from photoinhibition. Alternatively, the increase in Φf, D might protect PSI from photoinhibition that could be caused by the excessive electron flow from PSII. The observed increase in Φf, D must be some regulatory mechanism or at least some acclimatory response generally observed in cyanobacteria.

Materials and Methods

Strains and growth conditions

Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, Anabaena sp. PCC7120, N. punctiforme ATCC29133, Nostoc sp. HK-01, A. platensis NIES-39 and A. marina MBIC11017 were grown at 30°C and bubbled with air under continuous illumination at 200 µmol m−2 s−1. Acaryochloris marina was grown in IMK medium in sea water (Nihon Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.), A. platensis in SOT medium (Ogawa and Terui 1970) and the other species in BG-11 medium (Allen 1968). Cells of all the strains, except for Nostoc sp. HK-01, were sampled in the logarithmic phase. In the case of Nostoc sp. HK-01, cells were in a more or less aggregated form so that we could not judge whether this species was in the logarithmic phase, at least not simply from the measurements of optical density of the cells at 750 nm. For optical measurements, we suspended the cells of Nostoc sp. HK-01 to make as uniform a suspension as possible.

Fluorometer measurements

Chl fluorescence was measured with a pulse-amplitude fluorometer (WATER-PAM; Waltz) as described earlier (Ogawa et al. 2013). Cells in 2 ml of liquid culture were dark-adapted for 15 min and the minimum fluorescence level (Fo) was determined with a measuring light (peak at 650 nm). A 0.8 s flash of saturating light was given to determine Fm′dark. Subsequently, red actinic light (peak at 660 nm) of different PFDs (31.5, 167, 562 and 1,190 µmol m−2 s−1) was applied in a stepwise manner every 5 min to monitor fluorescence under the steady-state condition (Fs). At the end of each step, saturating light was applied to monitor the maximum fluorescence of the light-acclimated cells (Fm′). Then, actinic light was turned off and cells were relieved for 20 min from the effect of actinic light. Finally, cells were illuminated by actinic light for 4 min in the presence of 10 µM DCMU, and saturating light was applied to monitor the level of maximum fluorescence (Fm). The cell suspension was stirred at all times during the experiment. Fluorescence parameters were calculated as follows; qP = (Fm′ – Fs)/(Fm′ – Fo′) (Van Kooten and Snel 1990), ΦPSII = (Fm′ – Fs)/Fm′ (Bilger et al. 1995, Genty et al. 1989), ΦNPQ = Fs/Fm′ – Fs/Fm and Φf, D = Fs/Fm (Hendrickson et al. 2004). Fo′ was calculated as Fo′ = Fo/[(Fv/Fm) + (Fo/Fm′)] (Oxborough and Baker 1997). qP in the dark was calculated as qP = (Fm′dark – Fo)/(Fm′dark – Fo′) where Fo′ = Fo/[(Fv/Fm) + (Fo/Fm′dark)].

Absorbance spectra

Absorbance spectra were determined with a spectrophotometer (V-650; JASCO) equipped with an integrating sphere (ISV-722; JASCO) as described previously (Ogawa et al. 2013) at room temperature. The absorbance of the cell suspension was determined in a cuvette with a light path length of 5 mm. Each absorbance spectrum was normalized at the maximum absorbance in the respective spectrum. PC and Chl content were calculated as [PC] = 138.5×A620 – 35.49×A678 and [Chl a] = 14.97×A678 – 0.615×A620 according to Arnon et al. (1974).

77 K fluorescence emission spectra

77 K fluorescence emission spectra were determined with a fluorescence spectrometer (FP-8500; JASCO) with a low temperature attachment (PU-830; JASCO) as described earlier (Ogawa et al. 2013). Cell suspensions of cyanobacterial strains were adjusted to a concentration of 2 µg Chl ml−1 in the respective growth medium. The Chl concentration was determined by extraction with 100% methanol according to Grimme and Boardman (1972).

Prior to the measurements, the cells were either dark-acclimated for 15 min or illuminated by using a light source (PICL-NRX, NIPPON P-I) in the presence of 10 µM DCMU for 4 min. The samples were excited by 625 nm light (excitation slit width at 10 nm) for PC excitation. The fluorescence spectra were recorded with a fluorescence slit width of 2.5 nm and resolution of 0.2 nm. The spectra were averaged for three independent cultures and corrected for the sensitivity of the photomultiplier and the spectrum of light source using a secondary standard light source (ESC-842; JASCO).

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- NDH

NADPH dehydrogenase

- NPQ

non-photochemical quenching

- OCP

orange carotenoid protein

- PC

phycocyanin

- PFD

photon flux density

- PQ

plastoquinone

References

- Allen M.M. (1968) Simple conditions for growth of unicellular blue-green algae on plates. J. Phycol. 4: 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki M., Katoh S. (1982) Oxidation and reduction of plastoquinone by photosynthetic and respiratory electron transport in a cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 682: 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Arnon D.I., McSwain B.D., Tsujimoto H.Y., Wada K. (1974) Photochemical activity and components of membrane preparations from blue-green algae. I. Coexistence of two photosystems in relation to chlorophyll a and removal of phycocyanin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 357: 231–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellafiore S., Barneche F., Peltier G., Rochaix J.-D. (2005) State transitions and light adaptation require chloroplast thylakoid protein kinase STN7. Nature 433: 892–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilger W., Schreiber U., Bock M. (1995) Determination of the quantum efficiency of photosystem II and of non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence in the field. Oecologia 102: 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D., Öquist G. (1996) Predicting light acclimation in cyanobacteria from nonphotochemical quenching of photosystem II fluorescence which reflects state transition in these organisms. Plant Physiol. 111: 1293–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D., Hurry V., Clarke A.K., Gustafsson P., Öquist G. (1998) Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis of cyanobacterial photosynthesis and acclimation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62: 667–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B., Adams W.W., III (1996) The role of xanthophyll cycle carotenoids in the protection of photosynthesis. Trend. Plant Sci. 1: 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Emlyn-Jones D., Ashby M.K., Mullineaux C.W. (1999) A gene required for the regulation of photosynthetic light-harvesting in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Mol. Microbiol. 33: 1050–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori T., Hihara Y., Sonoike K. (2005) PsaK2 subunit in photosystem I is involved in state transition under high light condition in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 22191–22197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B., Briantais J.-M., Baker N.R. (1989) The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 990: 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Goss R., Lepetit B. (2015) Biodiversity of NPQ. J. Plant Physiol. 172: 13–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme L.H., Boardman N.K. (1972) Photochemical activities of a particle fraction P 1 obtained from the green alga Chlorella fusca. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 49: 1617–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson L., Furbank R.T., Chow W.S. (2004) A simple alternative approach to assessing the fate of absorbed light energy using chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynth. Res. 82: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraide Y., Oshima K., Fujisawa T., Uesaka K., Hirose Y., Tsujimoto R., et al. (2014) Loss of cytochrome cM stimulates cyanobacterial heterotrophic growth in the dark. Plant Cell Physiol. 56: 334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi M., Uebayashi N., Sato F., Endo T. (2014) Physiological functions of PsbS-dependent and PsbS-independent NPQ under naturally fluctuating light conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 55: 1286–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida S., Morita K.I., Kishine M., Takabayashi A., Murakami R., Takeda S., et al. (2011) Allocation of absorbed light energy in PSII to thermal dissipations in the presence or absence of PsbS subunits of rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 52: 1822–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilovsky D. (2007) Photoprotection in cyanobacteria: the orange carotenoid protein (OCP)-related non-photochemical-quenching mechanism. Photosynth. Res. 93: 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause G.H., Weis E. (1991) Chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis: the basics. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 42: 313–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kusama Y., Inoue S., Jimbo H., Takaichi S., Sonoike K., Hihara Y., et al. (2015) Zeaxanthin and echinenone protect the repair of photosystem II from inhibition by singlet oxygen in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 56: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H., Endo T., Schreiber U., Ogawa T., Asada K. (1992) Electron donation from cyclic and respiratory flows to the photosynthetic intersystem chain is mediated by pyridine nucleotide dehydrogenase in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 33: 1233–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Mi H., Endo T., Schreiber U., Ogawa T., Asada K. (1994) NAD(P)H dehydrogenase-dependent cyclic electron flow around photosystem I in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803: a study of dark-starved cells and spheroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 35: 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita H., Ikemoto H., Kurano N., Adachi K., Chihara M., Miyachi S. (1996) Chlorophyll d as a major pigment. Nature 383: 402. [Google Scholar]

- Mullineaux C.W., Allen J.F. (1990) State 1–State 2 transitions in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus 6301 are controlled by the redox state of electron carriers between photosystems I and II. Photosynth. Res. 23: 297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T., Harada T., Ozaki H., Sonoike K. (2013) Disruption of the ndhF1 gene affects Chl fluorescence through state transition in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, resulting in apparent high efficiency of photosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 54: 1164–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T., Terui G. (1970) Studies on the growth of Spirulina platensis. (I) On the pure culture of Spirulina platensis. J. Ferment. Technol. 48: 361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Oxborough K., Baker N.R. (1997) Resolving chlorophyll a fluorescence images of photosynthetic efficiency into photochemical and non-photochemical components—calculation of qP and Fv′/Fm′ without measuring Fo′. Photosynth. Res. 54: 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Park K.N. (2013) Morphological acclimation to light and partitioning of energy absorbed by leaves in Saxifraga nivalis and Saxifraga moschata subsp. Basaltica. Opera Corcontica 50: 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Peschek G.A., Schmetterer G. (1982) Evidence for plastoquinol-cytochrome f/b563 reductase as a common electron donor to P700 and cytochrome oxidase in cyanobacteria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 108: 1188–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaas T., Berteotti S., Ballottari M., Flieger K., Bassi R., Wilhelm C., et al. (2015) Non-photochemical quenching and xanthophyll cycle activities in six green algal species suggest mechanistic differences in the process of excess energy dissipation. J. Plant Physiol. 172: 92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippka R., Herdman M., (1992) Pasteur Culture Collection of Cyanobacterial Strains in Axenic Culture, Catalogue and Taxonomic Handbook. Institut Pasteur, Paris. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber U., Endo T., Mi H., Asada K. (1995) Quenching analysis of chlorophyll fluorescence by saturation pulse method: particular aspects relating to the study of eukaryotic algae and cyanobacteria. Plant Cell Physiol. 36: 873–882. [Google Scholar]

- Stransky H., Hager A. (1970) The carotenoid pattern and occurrence of light induced xanthophyll cycle in various classes of algae. IV. Cyanophyceae and Rhodophyceae. Arch. Mikrobiol. 72: 84–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kooten O., Snel J.F.H. (1990) The use of chlorophyll fluorescence nomenclature in plant stress physiology. Photosynth. Res. 25: 147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Hu Y., Luo H., Chow W.S., Zhang W. (2011) Two distinct strategies of cotton and soybean differing in leaf movement to perform photosynthesis under drought in the field. Funct. Plant Biol. 38: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]