Abstract

Incidence of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is increasing. Most patients have advanced disease at diagnosis and therapeutic options in this setting are limited. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel regimen was demonstrated to increase survival compared with gemcitabine monotherapy and is therefore indicated as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic PDAC and performance status Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 0-2. The safety profile of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel combination includes neutropenia, fatigue, and neuropathy as most common adverse events of grade 3 or higher. No case of severe hyponatremia associated with the use of nab-paclitaxel for the treatment of PDAC has been reported to date.

We report the case of a 72-year-old Caucasian man with a metastatic PDAC treated with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel regimen, who presented with a severe hyponatremia (grade 4) caused by a documented syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). This SIADH was attributed to nab-paclitaxel after a rigorous imputability analysis, including a rechallenge procedure with dose reduction. After dose and schedule adjustment, nab-paclitaxel was pursued without recurrence of severe hyponatremia and with maintained efficacy.

Hyponatremia is a rare but potentially severe complication of nab-paclitaxel therapy that medical oncologists and gastroenterologists should be aware of. Nab-paclitaxel-induced hyponatremia is manageable upon dose and schedule adaptation, and should not contraindicate careful nab-paclitaxel reintroduction. This is of particular interest for a disease in which the therapeutic options are limited.

Keywords: chemotherapy, hyponatremia, imputability, pancreatic cancer, taxanes, vasopressin

1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is increasing in incidence and is expected to become the second cause of cancer death in the United States by 2030.[1] In the vast majority of cases (80%), diagnosis is made at an advanced stage, when patients already have metastases or locoregional extension precluding curative surgical resection.[2] Therapeutic options in this setting remain limited. Since 1997 and until 2011, gemcitabine has been the only validated chemotherapy regimen for advanced PDAC, yielding median overall survival (OS) of 6 months. During the 5 past years, 2 phase III studies demonstrated that the FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil [5FU], irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) and then the gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel regimens significantly improve survival in patients with metastatic PDAC, with median OS reaching 11.1 and 8.5 months, respectively.[3,4] Both regimens are currently considered standards of care for first-line treatment in patients with advanced PDAC and good general condition (performance status [PS] Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] 0-1 for FOLFIRINOX, and PS ECOG 0-2 for gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel).

Nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane) is a solvent-free, albumin-coupled formulation of paclitaxel. Paclitaxel is an antimicrotubule agent for which efforts have been channeled into developing solvent-free formulations to reduce Cremophor-related neurotoxicity and allergic reactions.[5,6] Albumin is a natural, not immunogenic, circulatory transporter of hydrophobic molecules with reversible, noncovalent binding characteristics, representing an attractive candidate for drug delivery. Nab-paclitaxel is obtained by mixing paclitaxel with human albumin at high pressure to form 130-nm albumin-drug stable nanoparticles.[6] This technology allows intravenous administration of paclitaxel without solvent-related risks, avoids premedication and long infusion times, and may have a more predictable pharmacokinetic profile.

The safety profile of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel combination includes neutropenia (38%), fatigue (17%), and neuropathy (17%) as most common adverse events of grade 3 or higher according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0.[4] No case of severe hyponatremia associated with the use of nab-paclitaxel for the treatment of PDAC has been reported to date.

We here report the case of a 72-year-old Caucasian man with a metastatic PDAC treated with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel regimen, who presented a severe hyponatremia (grade 4) caused by a documented syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). This SIADH was attributed to nab-paclitaxel after a rigorous imputability analysis, including a rechallenge procedure with dose reduction. After dose and schedule adjustment, nab-paclitaxel was pursued without recurrence of severe hyponatremia and with maintained efficacy.

2. Case presentation

2.1. Initial presentation and management

A 72-year-old Caucasian man was referred to our oncology department for the therapeutic management of a stage IV PDAC metastatic to the liver, developed on malignant intraductal papillary and mucinous neoplasm of the pancreatic head. The diagnosis had been histologically proven by ultrasound-guided biopsy of a liver lesion showing adenocarcinoma cells with strong immunostaining for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK19, and no expression of CK20, CDX2, or TTF1. A thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computer-assisted tomodensitometry (TAP-CT) showed the primary pancreatic tumor and 2 liver lesions with imaging features compatible with metastases, and no evidence of disease extension to the peritoneum, thorax, or bones. The patient had a history of several basocellular carcinoma lesions that had been treated by local excision and without currently active skin lesions. He also had arterial hypertension and had presented a cardiorespiratory arrest due to myocardial infarction without neurological damage 4 months before PDAC diagnosis; the latest transthoracic echocardiography showed recovery to normal left ventricular ejection fraction. He had recently stopped smoking cigarettes (total consumption: 5 pack-year) and did not have history of alcohol or drug abuse.

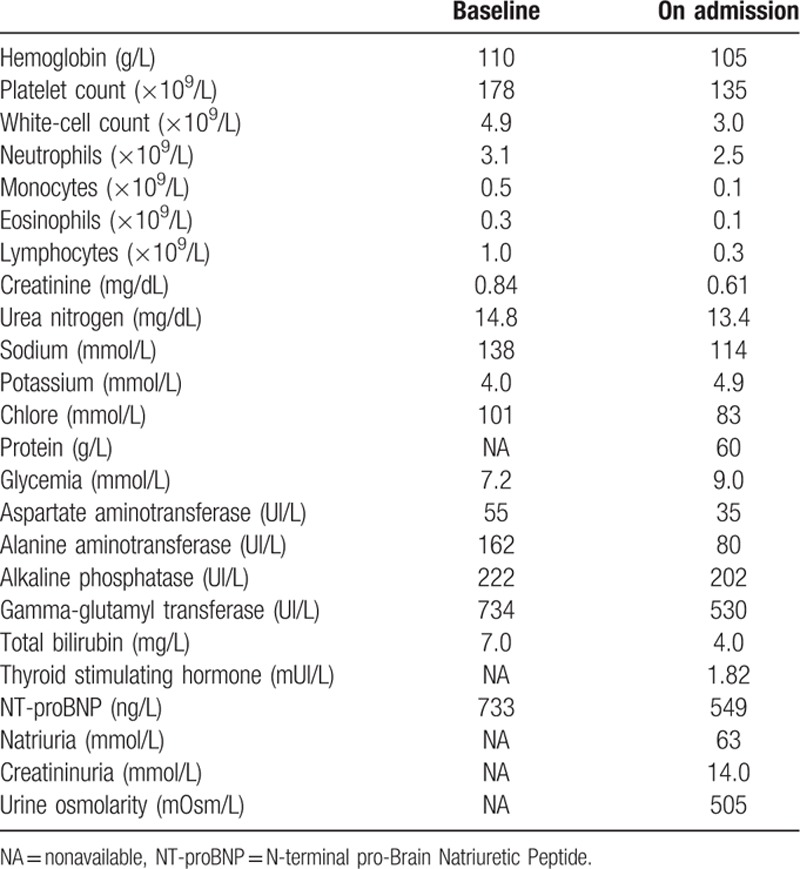

Current medications at diagnosis consisted in aspirin, ticagrelor, valsartan, bisoprolol, amlodipine, atorvastatin, and pancreatic enzymes. A metallic biliary stent had been placed endoscopically, due to jaundice related to main bile duct compression by the primary tumor. The patient was PS ECOG 0, asymptomatic, with conserved nutritional status and normal bilirubin level after biliary drainage. Biological results at baseline are provided in Table 1. 5FU-based chemotherapy was contraindicated due to recent ischemic cardiac event. Then, first-line chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel combination (gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 and nab-paclitaxel 125 mg/m2 on day (D) 1, D8, and D15 of a 28-day cycle) was decided in multidisciplinary meeting.

Table 1.

Summary of the biological results of the patient.

The patient was hospitalized following the first administration of chemotherapy (cycle 1 D1) due to a biliary hemorrhage and angiocholitis secondary to the biliary drainage, without hemodynamic instability, which resolved with endoscopic sclerosis and additional biliary stent placement, ticagrelor arrest, and intravenous antibiotherapy. An acute atrial arythmia episode led to the introduction of sodic tinzaparin.

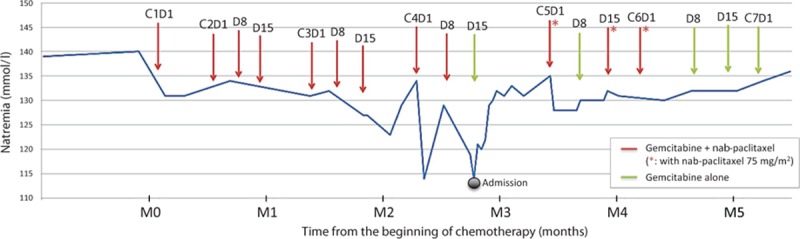

The 2 following chemotherapy cycles (cycles 2 and 3) were unremarkable. The patient was clinically asymptomatic and presented good hematological tolerance of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel combination (Table 1). No dose adaptation was required. A progressive decrease in natremia level was observed but remained >130 mmol/L, with preserved renal function (Fig. 1). The TAP-CT after 3 chemotherapy cycles showed stable disease (with a 15% decrease in the sum of the greatest diameter of target lesions) according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1 criteria. The serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) concentration had decreased from 120 UI/L (baseline) to 40 UI/L.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the patient's history with changes in the natremia level over time.

2.2. Diagnosis of SIADH

Following the administration of cycle 3 D15 of gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel, natremia decreased to 125 mmol/L. The patient was asymptomatic. Oral fluid restriction was advised. The natremia level returned to normal range before the beginning of cycle 4. Natremia fell again after administration of cycle 4 D1, and resolved within 1 week with fluid restriction.

The patient was admitted 6 days after administration of cycle 4 D8 due to severe hyponatremia (114 mmol/L) associated with asthenia and diffuse myalgia. He was PS ECOG 2. Blood pressure was 148/61 mm Hg and heart rate 58 bpm. Temperature was 36.7°C. Patient's weight was stable at 78 kg. He did not report diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, nor abdominal pain. There had been no change in his medications. He did not present clinical signs of extracellular dehydratation nor oedema. The neurological examination showed a slight slowness in ideation without any other abnormality. The remaining of the physical examination was unremarkable. Biological tests at admission are presented in Table 1. A cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was normal.

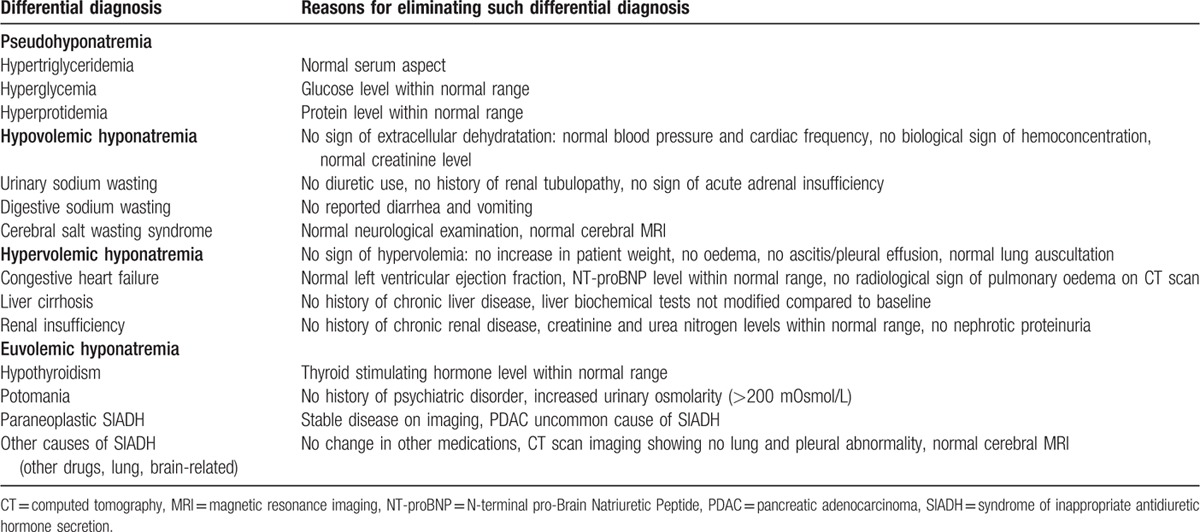

Overall, the patient presented with symptomatic (asthenia, myalgia, and slowness of ideation) grade 4 (according to CTCAE v4.0: < 120 mmol/L) euvolemic hyponatremia. There was no evidence for a pseudohyponatremia without hypotonicity, thyroid or adrenal insufficiency, nor potomania; other differential diagnoses are discussed in Table 2. The urinary sodium concentration (> 20 mmol/L) and osmolarity (> 200 mOsm/L) were unadapted, leading to the diagnosis of SIADH. There was no evidence of brain or lung lesions, which are the most frequent causes of SIADH. This SIADH could then be either paraneoplastic due to PDAC, or induced by medications. The recent imaging showing tumor control did not support the first hypothesis. We then performed a rigorous imputability investigation.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis for hyponatremia in the patient.

2.3. Drug notoriety and imputability analysis

We conducted a systematic review of case reports published in the literature through Medline and PubMed (search terms: “hyponatremia” and “taxane,” “nab-paclitaxel,” “paclitaxel,” and “docetaxel”) and no studies specifically investigated the correlation between the SIADH occurrence and nab-paclitaxel treatment. As our case was observed in France, we also carried out a search in the French Pharmacovigilance Database (FPD) which allows recording of spontaneous reports of Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) since 1985. We performed a query in the FPD selecting for analysis the preferred term “hyponatremia” in the database field of ADR and “nab-paclitaxel,” “paclitaxel,” and “docetaxel” in the database field of the drug. A total of 5 observations involving hyponatremia with paclitaxel or docetaxel were reported in the FPD. All of the observations were isolated hyponatremia with no other associated symptoms. Among them, observations displaying docetaxel were associated with other drugs such as carboplatin, cisplatin, or fluorouracil. No observation involving SIADH after nab-paclitaxel treatment was registered in the FPD.

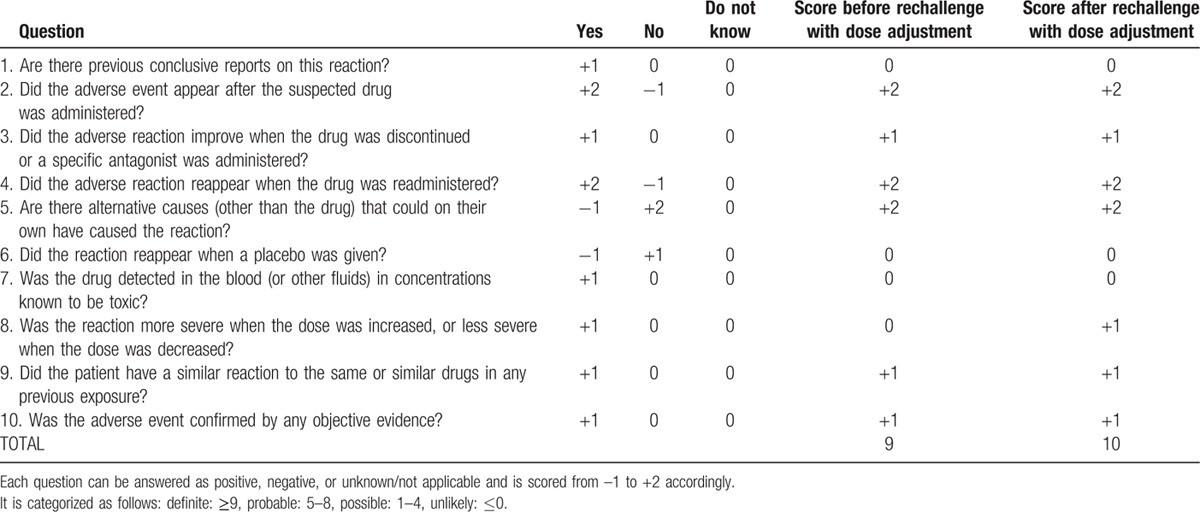

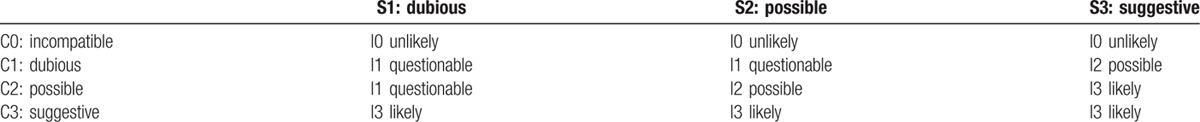

Causality assessment is the evaluation of the likelihood that a particular treatment is the cause of an observed adverse event. In the purpose of assessing the causative link between nab-paclitaxel and SIADH, we used the Naranjo algorithm and the French method of imputability.[7,8] Naranjo algorithm was developed in 1981 and it proposed an easier probability scale designed to sensitively monitor adverse events.[7] The Naranjo criteria classify the probability that an adverse event is related to drug therapy based on a list of weighted questions (Table 3). This scale allows categorical classification of adverse events as “definite,” “probable,” “possible,” or “doubtful” based on the answers to 10 questions. Points are given for 10 elements including time to onset, recovery, previous reports of similar injury, response to rechallenge, and possibility of alternative causes. Differential diagnosis and how they were ruled out are displayed in Table 2. The scores in the present case with Naranjo algorithm were 9 before dose adjustment of nab-paclitaxel and 10 after, which means a definite relationship between nab-paclitaxel and SIADH. The French Pharmacovigilance System's was also performed and a global imputability score I (I0, unlikely; I1, questionable; I2, possible; I3, likely) was the result of crossing the chronological and semiological criteria scores (Table 4).[8] The French method of imputability demonstrated a “very likely” imputability of nab-paclitaxel in the occurrence of SIADH in this case.

Table 3.

Naranjo scale questions and weighted score.

Table 4.

French imputability (I), chronological (C), and semiological (S) scores crossing table.

2.4. Clinical management

Patient was treated with hypertonic fluid intravenous administration and oral fluid restriction. Natremia gradually increased to 130 mmol/L within 1 week, and this level was maintained after stopping intravenous infusion. Asthenia (PS), myalgia, and slowness of ideation completely resolved after natremia correction. Based on imputability investigations, cycle 4 D15 of chemotherapy was administered without nab-paclitaxel. Natremia remained stable. The next chemotherapy cycle was delayed by 1 week according to the patient's preference, wishing a chemo-break. After discussion of the case in multidisciplinary meeting, given the patient's preserved general condition and benefit from nab-paclitaxel on tumor control, it was proposed to reintroduce nab-paclitaxel carefully, at a reduced dosage of 75 mg/m2 and with close natremia monitoring, and to suspend nab-paclitaxel administration if natremia level was below 130 mmol/L. Based on this algorithm, nab-paclitaxel was pursued, and the patient received gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel 75 mg/m2 on D1 and D15 of the 2 following cycles (cycles 5 and 6). Natremia level fluctuated according to nab-paclitaxel administrations, but remained superior or equal to 125 mmol/L. This rechallenge at a lower dose raised the likelihood of causal and temporal association increasing from 9 to 10 the imputability score for Naranjo algorithm and showing that SIADH occurrence with nab-paclitaxel is certainly dose-dependent. The TAP-CT after a total of 6 cycles of gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel combination showed partial tumor response (residual target lesions under the measurement threshold), and serum CA19-9 level was 80 UI/L. The patient developed grade 3 neuropathy leading to nab-paclitaxel discontinuation from cycle 6 D8; he was otherwise asymptomatic. Chemotherapy was continued with weekly gemcitabine alone. Natremia levels remained superior or equal to 130 mmol/L. The patient is alive and without evidence of tumor progression 3 months after nab-paclitaxel discontinuation.

3. Discussion and conclusions

We herein report the case of a patient treated with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel combination for metastatic PDAC who presented a severe symptomatic hyponatremia (grade 4) caused by a documented SIADH. SIADH diagnosis is based on euvolemic hyponatremia with concentrated urine represented by an excessive urinary sodium concentration (>20 mmol/L) and urine hyperosmolarity (>200 mOsm/L) after ruling out hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency. In the present case, SIADH was attributed to nab-paclitaxel after a rigorous imputability analysis, including a rechallenge procedure at a reduced dose. We used both the Naranjo algorithm and the French method of imputability for causality analysis.[7,8] Whatever the method used, the imputability score remains at the highest level, which means a very likely and a definite likelihood for French method of imputability and for Naranjo algorithm, respectively. To our knowledge, our report represents the first case of SIADH due to nab-paclitaxel. Among the drugs commonly implicated as triggering drug-induced SIADH, anticancers drugs are often listed.[9] In studies evaluating taxanes (particularly, paclitaxel and docetaxel) cases of hyponatremia were observed, but these drugs were used in combination with other agents (including platinum salts), which have been reported to cause hyponatremia by themselves and are thus most probably responsible for this adverse event.[10–20] SIADH in cancer patients may be driven by ectopic production of vasopressin by tumors, pulmonary or neurologic disorders, or by effects of chemotherapy and palliative medications on vasopressin production or action.[9] The mechanisms by which chemotherapy causes SIADH are not fully elucidated. Nevertheless, several hypotheses have been proposed, including: stimulation of vasopressin release by the pituitary gland, sensitization of the kidney to vasopressin action, direct vasopressin-like action of the drug on the kidney, or inhibition of the vasopressinase activity, resulting in prolonged vasopressin half-life.[9,21] Other factors may cause hypovolemic hyponatremia, including diarrhea and vomiting caused by cancer therapy.[9]

Based on our observation, natremia level should be checked in patients with PDAC treated by nab-paclitaxel and experiencing unusual asthenia, myalgia, or neurological symptoms, to search for hyponatremia. Moreover, our case raises the question of natremia monitoring in patients treated by nab-paclitaxel. Of note, the underlying mechanisms of nab-paclitaxel-induced SIADH are unknown and no susceptibility factors are identified. Multiple alterations in the regulation of water homeostasis are observed in the elderly.[22] These age-associated abnormalities include enhanced secretion of vasopressin, inability to appropriately suppress vasopressin secretion during fluid intake, and intrinsic inability to maximally excrete free water, the combination of which results in increased susceptibility to SIADH in this patient group.[22] Therefore, our patient's age (72-year old) may have played a role in the cause of this drug-induced adverse effect. Healthcare professionals should take special care when they use nab-paclitaxel in elderly patients, as well as in those with a history of kidney, heart, or liver disease and/or with any concomitant drug known to induce hyponatremia (e.g., diuretics, serotonin uptake inhibitors).[23]

This case also illustrates that nab-paclitaxel-induced hyponatremia is manageable upon dose and schedule adaptation, and should not contraindicate careful nab-paclitaxel reintroduction. This is of particular interest for a disease in which the therapeutic options are limited.

To sum up, hyponatremia is a rare but potentially severe complication of nab-paclitaxel therapy that medical oncologists and gastroenterologists should be aware of.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 5FU = 5-fluorouracil, ADR = adverse drug reaction, CA 19-9 = carbohydrate antigen 19-9, CTCAE = Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, FPD = French Pharmacovigilance Database, NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide, OS = overall survival, PDAC = pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, RECIST = Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, SIADH = inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, TAP-CT = thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography.

The patient has given his consent for the Case Report to be published (see attached signed consent form).

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res 2014; 74:2913–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:2140–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gradishar WJ. Albumin-bound paclitaxel: a next-generation taxane. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2006; 7:1041–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guarneri V, Dieci MV, Conte P. Enhancing intracellular taxane delivery: current role and perspectives of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012; 13:395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981; 30:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Begaud B, Evreux JC, Jouglard J, Lagier G. [Imputation of the unexpected or toxic effects of drugs. Actualization of the method used in France]. Therapie 1985; 40:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castillo JJ, Vincent M, Justice E. Diagnosis and management of hyponatremia in cancer patients. Oncologist 2012; 17:756–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe T, Takeda K, Ohe Y, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing weekly docetaxel plus cisplatin versus docetaxel monotherapy every 3 weeks in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the intergroup trial JCOG0803/WJOG4307L. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noronha V, Joshi A, Jandyal S, et al. High pathologic complete remission rate from induction docetaxel, platinum and fluorouracil (DCF) combination chemotherapy for locally advanced esophageal and junctional cancer. Med Oncol 2014; 31:188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hironaka S, Tsubosa Y, Mizusawa J, et al. Phase I/II trial of 2-weekly docetaxel combined with cisplatin plus fluorouracil in metastatic esophageal cancer (JCOG0807). Cancer Sci 2014; 105:1189–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loong HH, Winquist E, Waldron J, et al. Phase 1 study of nab-paclitaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil as induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locoregionally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50:2263–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura Y, Yano H, Imamura H, et al. A phase I study of triplet combination chemotherapy of paclitaxel, cisplatin and S-1 in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013; 43:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshikawa T, Tsuburaya A, Hirabayashi N, et al. A phase I study of palliative chemoradiation therapy with paclitaxel and cisplatin for local symptoms due to an unresectable primary advanced or locally recurrent gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2009; 64:1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajo A, Hokita S, Ishigami S, et al. A multicenter phase II study of biweekly paclitaxel and S-1 combination chemotherapy for unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2008; 62:1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen MH, Gootenberg J, Keegan P, et al. FDA drug approval summary: bevacizumab (Avastin) plus Carboplatin and Paclitaxel as first-line treatment of advanced/metastatic recurrent nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist 2007; 12:713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohe Y, Niho S, Kakinuma R, et al. A phase II study of cisplatin and docetaxel administered as three consecutive weekly infusions for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in elderly patients. Ann Oncol 2004; 15:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koizumi T, Tsunoda T, Fujimoto K, et al. Phase I trial of weekly docetaxel combined with cisplatin in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2001; 34:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosomi Y, Ohe Y, Mito K, et al. Phase I study of cisplatin and docetaxel plus mitomycin C in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1999; 29:546–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liamis G, Milionis H, Elisaf M. A review of drug-induced hyponatremia. Am J Kidney Dis 2008; 52:144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowen LE, Hodak SP, Verbalis JG. Age-associated abnormalities of water homeostasis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2013; 42:349–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoorn EJ, Lindemans J, Zietse R. Development of severe hyponatraemia in hospitalized patients: treatment-related risk factors and inadequate management. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21:70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]