Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an emerging pathogen that infects the skin and soft tissue. However, there are few reports of renal complications from MRSA involving immunoglobulin (Ig)A-dominated rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (GN). Favorable renal outcomes from IgA GN are achieved by administering timely therapy. In the present study, we describe the case of a healthy young woman suffering from a cutaneous MRSA infection that initially presented with gross hematuria. Six months after eradicating the infection, severe impairment of renal function was noted because of intractable nausea and vomiting. Renal pathology revealed advanced IgA nephropathy with fibrocellular crescent formation. An aggressive treatment plan using immunosuppressants was not adopted because of her irreversible renal pathology, and she was therefore administered maintenance hemodialysis.

This instructive case stresses the importance of being aware of the signs of IgA nephropathy post-MRSA infection, such as cutaneous lesions that are mostly painless and accompanied by hematuria and mild proteinuria. If the kidney cannot be salvaged, it will undergo irreversible damage with devastating consequences.

Keywords: hemodialysis, immunoglobulin-A nephropathy, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, rapid progress glomerulonephritis, renal impairment

1. Introduction

Historically, acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis (GN) is caused by Staphylococcus epidermidis and S. aureus, with typical findings of diffuse endocapillary proliferation and exudative GN on light microscopy, C3-dominant deposits with or without immunoglobulin (Ig)G codeposition on immunofluorescence, and subepithelial hump-shaped deposits on electron microscopy.[1,2] A third pattern was recently described, termed superantigen-related GN or acute postmethicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) GN, with the distinguishing feature of IgA- or IgA-codominant mesangial staining.[3]

Most of the causative pathogens of this disease are MRSAs, and favorable renal outcomes have been reported after timely administration of antibiotics and adequate immunosuppressant therapy.[4,5] Regarding the emerging importance of MRSA-related IgA nephropathy, we present a patient who had an MRSA infection without awareness of early sign of GN, resulting in a devastating renal outcome with crescent formation from IgA-dominant postinfectious GN.

2. Case report

A 22-year-old native Taiwanese woman was referred for the evaluation of rapidly developing advanced renal failure. Her medical history was unremarkable, and she had no personal or family history of the illness. A total of 6 months before referral, she had a community-acquired skin infection, initially in the left foot. Subsequently, she developed a skin abscess in the left posterolateral trunk with a pus culture that yielded MRSA. In addition to 2 weeks of antibiotic treatment with intravenous vancomycin (1 g/8 hour), an open surgical incision was performed. After her cutaneous infection resolved, painless gross hematuria occurred within 2 weeks. She believed that it was related to menstruation and did not receive further medical attention. Then, her serum creatinine (Cr) level was 1.2 mg/dL (reference: 0.5–1.3 mg/dL).

She was conscious on admission with a temperature of 35.8°C, heart rate of 67 beats/minute, and blood pressure of 156/89 mm Hg. Examination of her heart, chest, and abdomen was unremarkable. The results of the laboratory tests of her serum were as follows: blood urea nitrogen, 60 mg/dL (reference: 7–25 mg/dL); Cr, 6.8 mg/dL; sodium, 137 mEq/L (reference: 133–145 mEq/L); potassium, 4.5 mEq/L (reference: 3.3–5.1 mEq/L); intact calcium, 4.58 mg/dL (reference: 3.68–5.6 mg/dL); phosphate, 4.6 mg/dL (reference: 2.5–5 mg/dL); uric acid, 5.6 mg/dL; total protein, 4.6 g/dL (reference: 6.0–8.5 g/dL); albumin, 3.3 g/dL (reference: 3.5–5.0 g/dL); and hemoglobin, 9.1 g/dL (reference: 12–14 g/dL). She had low serum levels of C3 (38.2 mg/dL; reference: 79–152 mg/dL) and C4 (11.8 mg/dL; reference: 16–38 mg/dL). Her immunoglobulin levels were as follows: IgG, 418 mg/dL (reference: 751–1560 mg/dL); IgA, 135 mg/dL (reference: 82–453 mg/dL); and IgM, 32.9 mg/dL (reference: 46–304 mg/dL). Serological test results were all negative for antinuclear antibody, anti-DNA antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antiglomerular basement membrane antibody, rheumatoid factor activity, hepatitis B surface antigen, and hepatitis C virus antibody. Urinalysis demonstrated a nephrotic range of proteinuria (4166 mg/24 hour, urine volume 1300 mL/day), 16–30 cells/high-power field, and sterile pyuria. Renal ultrasound demonstrated normal bilateral kidney size (right kidney, 10 cm; left kidney, 10.2 cm) but with increased cortical echogenicity.

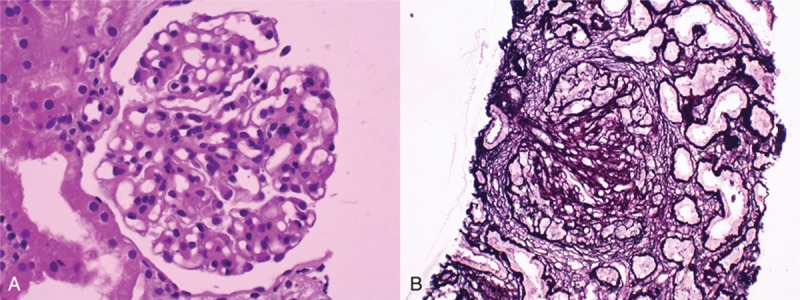

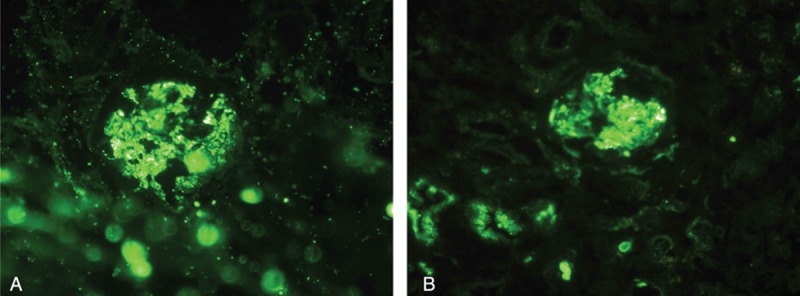

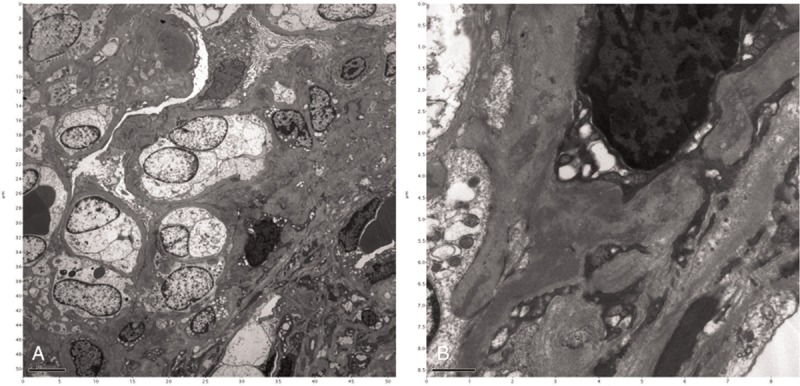

A diagnostic renal biopsy was performed because of the unknown cause of her acute renal failure. Light microscopy revealed 9 glomeruli with 6 globally sclerotic glomeruli, 1 segmented sclerotic glomerulus, and 2 glomeruli with fibrocellular crescent formation. Moderate mesangial proliferation and matrix expansion was noted. An inflammatory infiltrate of mononuclear cells, diffuse interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy were observed (Fig. 1). Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated diffuse global granular-predominant IgA staining (2+) with less intense C3 staining (1+) in the mesangium (Fig. 2). Electron microscopy revealed the effacement of podocyte foot processes, segmental expansion of the mesangial matrix, and electron-dense material in the mesangial area. There were no hump-shaped subepithelial deposits (Fig. 3). She was diagnosed with advanced IgA nephropathy with some crescent formation.

Figure 1.

Glomerulus demonstrating (A) segmentally sclerotic change (periodic acid–Schiff stain, ×600) and (B) mesangial proliferation with fibrocellular crescent formation (Jones’ silver stain, ×600).

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence staining for (A) IgA scored as 2+ and (B) C3 scored as 1+ granular deposition in the mesangium and glomerular capillary loops (original magnification ×600).

Figure 3.

Electron microscopy demonstrating (A) expansion of the mesangial matrix (original magnification ×4000) and (B) electron-dense deposits in the mesangium (original magnification ×20,000).

According to these clinicopathological correlations, she was further diagnosed with crescentic IgA nephropathy secondary to MRSA infection. She had irreversible renal pathological change; therefore, plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapies were not prescribed. Subsequently, she underwent maintenance dialysis.

3. Discussion

In 1961, Powell[2] first identified staphylococcal infection as the cause of GN. Typically, postinfectious GN is dominated by IgG, detected using immunofluorescence, and by the presence of immune complex depositions with characteristic humps in the subepithelial areas of glomerular basement membranes. Recently, a new type of IgA-dominated postinfectious GN was described that is frequently associated with MRSA infections. The first cases of GN associated with MRSA infections were reported in 1995.[3] The main clinical characteristics are as follows: insidious onset of rapidly progressive renal failure, hematuria, and proteinuria[6] associated with different types of proliferative GN and varying degrees of crescent formation accompanied by codominant glomerular deposition of IgA.[6] The cause of IgA post-MRSA GN remains unknown. One hypothesis implicates bacterial enterotoxins produced by MRSA as superantigens that lead to T cell activation, release of cytokines, and antibody production, such as IgA.[3,7] The development of monoclonal antibodies to S. aureus cell envelope antigen proved the existence of marked deposition found in the glomeruli.[8] Subsequently, this disease was detected in patients at an increased frequency than before the use of monoclonal antibodies.[4–6,8–17]

IgA-dominant MRSA-GN is often mistaken for idiopathic IgA nephropathy because of its similar immunofluorescence pattern. Findings favoring MRSA-GN over IgA nephropathy are as follows: hypocomplementemia, intercurrent staphylococcal infection, diffuse endocapillary hypercellularity with prominent neutrophil infiltration detected using light microscopy, and subepithelial humps detected using electron microscopy.[15] However, the characteristic subepithelial hump-shaped deposits are present in only 20% of patients.[4] The hypotheses proposed to explain this feature are as follows: In contrast to IgG deposits that are resorbed, IgA deposited in poststaphylococcal GN persists even when the disease resolves. IgA-dominant MRSA-GN is a secondary form of IgA nephropathy.[18] Our patient's characteristics were consistent with the diagnosis of IgA-dominant MRSA-GN, according to the findings described above. In our case, a subepithelial hump was absent, which may be due to the delayed finding of GN.

Most patients with IgA-dominant MRSA-GN experience a fulminant course of acute renal failure, severe proteinuria, and variable hematuria. However, after early eradication of MRSA infection using an antibiotic, there have been reports of renal function recovering in patients.[13] A separate report revealed the eradication of MRSA infection and restoration of renal function after additional steroid treatment.[16] However, considering that infection causes this disease, aggressive steroid pulse therapy and immunosuppressant treatment for rapidly progressive crescentic GN is dangerous. Moreover, steroid therapy may induce a latent MRSA infection with potential for activation. Therefore, we suggest controlling the MRSA infection first with adequate antibiotics and then treating it according to the guideline for IgA nephropathy.[19] Conservative therapy of renin-angiotensin system blockade with blood pressure control was initiated while the proteinuria was 0.5 to 1 g/day. An add-on steroid therapy was administrated only when persistent proteinuria >1 g/day and glomerular filtrate rate >50 mL/minute per 1.73 m2 was detected after 3 to 6 months of optimized supportive care.

Glomerular crescent formation is an uncommon occurrence in this new type of poststaphylococcal GN and complicates the clinical outcome. In total, 11 patients with this entity have been described in the literature; 9 were infected with MRSA, and 1 was infected with methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus.[4–6,8,9,14,17] The clinical characteristics of these patients included at least 1 with glomerular crescent formation on renal biopsy. In total, 6 patients received immunosuppressive therapy as well as antibiotics. All patients recovered partial renal function; however, 2 died because of infectious complications. The use of immunosuppressive therapy in this setting is unclear due to limited supporting evidence in literature. We suggest that immunosuppressant use should be considered when the patient's renal function deteriorates after well controlling the underlying MRSA infection. In our patient, although her skin infection resolved long before her admission, renal pathology was irreversible due to advanced fibrocellular crescent formation. Therefore, more aggressive treatment was not indicated, and she permanently lost her renal function at a young age.

4. Conclusion

Because the incidence of MRSA infection is increasing, IgA crescentic GN due to MRSA may become a significant health issue. We emphasize the importance of being alert to the signs of GN when examining patients with prior MRSA infection because early intervention can rescue kidney function. We suggest conducting routine checks of patients’ urine using a dipstick post-MRSA infection to detect MRSA-related GN without delay.

Acknowledgment

We thank our patient for contributing clinical data to this report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Cr = creatinine, GN = glomerulonephritis, Ig = immunoglobulin, MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Ethical statement: Ethical approval was not required for this study as our study was focused on the retrospective observation of a patient's hospital course, which in no way affected his treatment. Informed consent was obtained from the patient regarding the reporting and publication of this case report.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Arze RS, Rashid H, Morley R, et al. Shunt nephritis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Nephrol 1983; 19:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell DE. Non-suppurative lesions in staphylococcal septicaemia. J Pathol Bacteriol 1961; 82:141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koyama A, Kobayashi M, Yamaguchi N, et al. Glomerulonephritis associated with MRSA infection: a possible role of bacterial superantigen. Kidney Int 1995; 47:207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YR, Wen YK. Favorable outcome of crescentic IgA nephropathy associated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Ren Fail 2011; 33:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley AM, Wall BM, Cooke CR. Favorable outcome after aggressive treatment of infection in a diabetic patient with MRSA-related IgA nephropathy. Am J Med Sci 2009; 337:221–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worawichawong S, Girard L, Trpkov K, et al. Immunoglobulin A-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis: frequent occurrence in nondiabetic patients with Staphylococcus aureus infection. Hum Pathol 2011; 42:279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoh K, Kobayashi M, Hirayama A, et al. A case of superantigen-related glomerulonephritis after methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection. Clin Nephrol 1997; 48:311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kai H, Shimizu Y, Hagiwara M, et al. Post-MRSA infection glomerulonephritis with marked Staphylococcus aureus cell envelope antigen deposition in glomeruli. J Nephrol 2006; 19:215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagaba Y, Hiki Y, Aoyama T, et al. Effective antibiotic treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-associated glomerulonephritis. Nephron 2002; 92:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasr SH, Markowitz GS, Whelan JD, et al. IgA-dominant acute poststaphylococcal glomerulonephritis complicating diabetic nephropathy. Hum Pathol 2003; 34:1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handa T, Ono T, Watanabe H, et al. Glomerulonephritis induced by methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Exp Nephrol 2003; 7:247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long JA, Cook WJ. IgA deposits and acute glomerulonephritis in a patient with staphylococcal infection. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:851–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoskar AA, Nadasdy G, Plaza JA, et al. Staphylococcus infection-associated glomerulonephritis mimicking IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1:1179–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashimoto M, Nogaki F, Oida E, et al. Glomerulonephritis induced by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection that progressed during puerperal period. Clin Exp Nephrol 2007; 11:92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nasr SH, Share DS, Vargas MT, et al. Acute poststaphylococcal glomerulonephritis superimposed on diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 2007; 71:1317–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuyama S, Wakui H, Maki N, et al. Successful treatment of post-MRSA infection glomerulonephritis with steroid therapy. Clin Nephrol 2008; 70:344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeledon JI, McKelvey RL, Servilla KS, et al. Glomerulonephritis causing acute renal failure during the course of bacterial infections. Histological varieties, potential pathogenetic pathways and treatment. Int Urol Nephrol 2008; 40:461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haas M, Racusen LC, Bagnasco SM. IgA-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis: a report of 13 cases with common ultrastructural features. Hum Pathol 2008; 39:1309–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapter 10: Immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2012; 2:209–217. [Google Scholar]