Abstract

Objective. To evaluate the structure and impact of student organizations on pharmacy school satellite campuses.

Methods. Primary administrators from satellite campuses received a 20-question electronic survey. Quantitative data analysis was conducted on survey responses.

Results. The most common student organizations on satellite campuses were the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) (93.1%), American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) (89.7%), Christian Pharmacists Fellowship International (CPFI) (60.0%), state organizations (51.7%), and local organizations (58.6%). Perceived benefits of satellite campus organizations included opportunities for professional development, student engagement, and service. Barriers to success included small enrollment, communication between campuses, finances, and travel.

Conclusion. Student organizations were an important component of the educational experience on pharmacy satellite campuses and allowed students to develop professionally and engage with communities. Challenges included campus size, distance between campuses, and communication.

Keywords: student organizations, professionalism, satellite campuses, leadership

INTRODUCTION

The number of colleges and schools of pharmacy with multiple, geographically dispersed campuses has steadily increased during the past decade. As of August 2014, 30 schools of pharmacy had established satellite campuses1 compared to 20 in 2009.2 Primary reasons for this growth is the need to increase student enrollment, expand access to experiential education resources, and improve recruitment and retention of pharmacists in particular areas, such as rural communities.2 Medical schools have also expanded regional medical campuses. According to the American Association of Medical Schools, there were 48 regional medical school campuses in 2014.3 Leaders in medicine have projected a shortage of 52 000 primary care physicians between 2010 and 2025, prompting medical schools to increase enrollment or to create 2-year or 4-year regional campuses to increase the number of graduates.4 The increased need for primary care physicians is a result of population growth, an aging population, and increased health insurance availability.4 Satellite campuses in medicine may have different missions from the main campus, including an emphasis on rural and community medicine.5

Although schools of pharmacy with satellite campuses have successfully expanded enrollment and enhanced use of clinical training sites,2 there have been challenges associated with developing distance campuses.2,6 Providing an equal educational experience for a student body spread across campuses can be challenging, especially when considering effective strategies to develop pharmacy student organizations.2 Since cocurricular and extracurricular activities such as participation in student organizations play an important role in the student experience,7-9 it is important to address the challenges that schools face when developing student organizations on satellite campuses. Schools with multiple campuses must demonstrate equivalence of curriculum, faculty members, and student support at distant campuses in order to meet Accreditation Council for Pharmaceutical Education (ACPE) Standards.10 The 2016 ACPE Standards include requirements related to cocurricular experiences that emphasize the importance personal and professional development.10

A review of the literature yielded a paucity of data related to pharmacy student organizations on satellite campuses. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the structure of pharmacy student professional organizations on satellite campuses including student leadership opportunities, types of student organizations offered, and the perceived benefits of student organizations for students on a distant campus.

METHODS

The ACPE website was evaluated to identify schools of pharmacy that included a main campus with one or more satellite campuses.1 At the time of this study, 30 schools of pharmacy had a main campus with at least one satellite campus, and seven schools had multiple distance campuses. A list of schools with satellite campuses in 2013 can be found in Appendix 1. A total of 40 satellite campuses were identified for the 30 schools of pharmacy. Since the time of the research project, some schools’ names have changed, and some satellite campuses have been added whereas others have closed. At the time of the project, the research team identified the primary administrator at each satellite campus by e-mailing and/or calling the satellite campus. Participation in the survey was voluntary and no incentives were provided. Consent to participate was implied by completion of the survey. This study was reviewed and exempted by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

A 20-question survey was developed by the research team based on previous research related to student organizations on satellite campuses, with significant input from a faculty member skilled in educational research and survey design. The survey was created using Qualtrics survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT), and a link to the survey was e-mailed to the previously identified primary administrators from each satellite campus. Questions included demographic information about the location, enrollment, structure, and leadership of the satellite campus, followed by questions about student organizations on the satellite campus. The survey ended with two open-text boxes asking about the perceived benefits of professional organizations and the barriers to development of successful student organizations on the satellite campus. The survey was launched in fall 2013 and remained open for eight weeks, and a survey reminder was sent two weeks after the initial e-mail. To improve the initial response rate, those who hadn’t completed the survey the first time were contacted individually and invited to complete it after the first 8-week window. Location and enrollment data was verified for accuracy via online search or phone follow up. All quantitative data analysis was conducted with Qualtrics. Continuous data are presented as mean (SD).

RESULTS

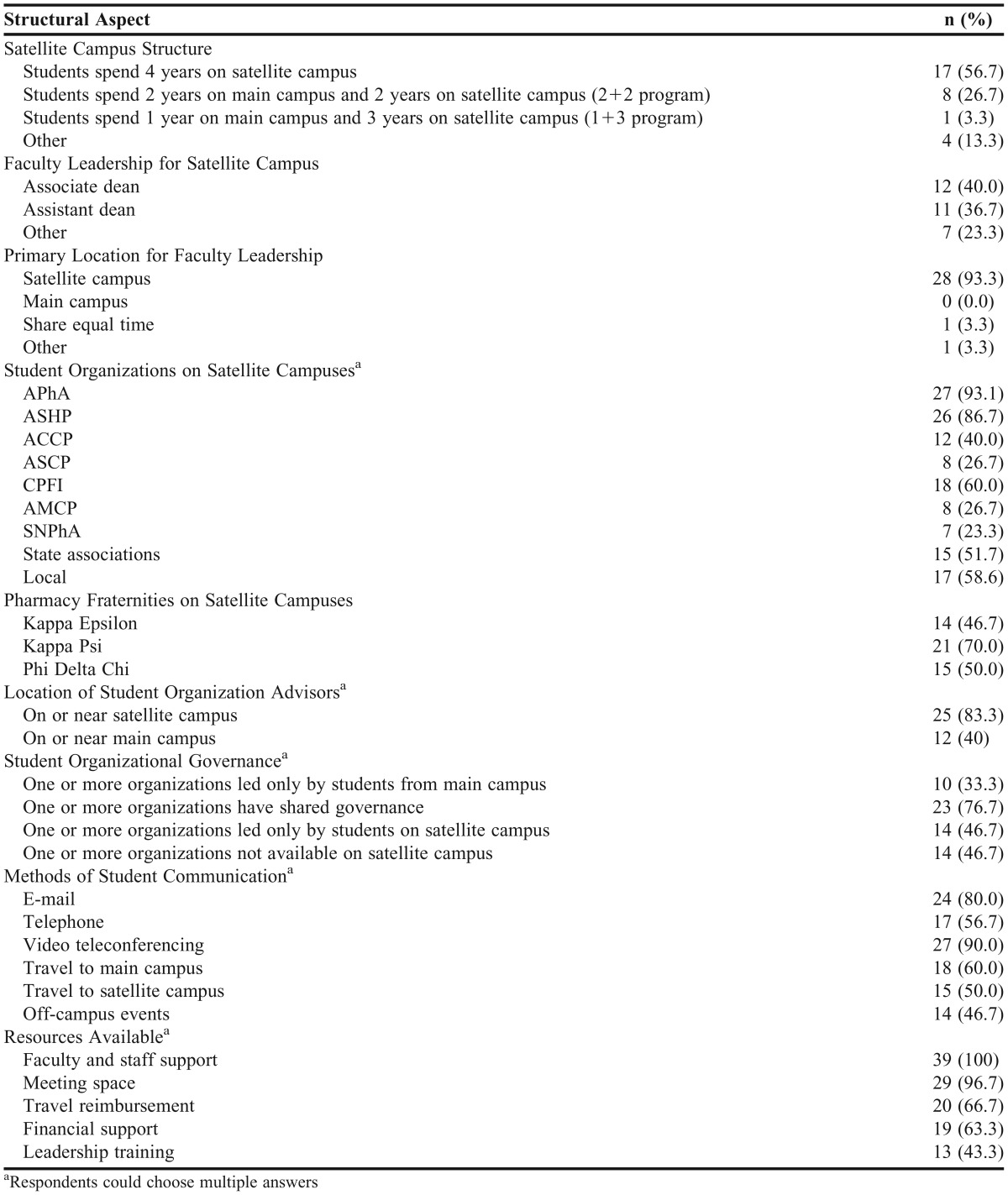

Twenty-five of the 30 schools of pharmacy with satellite campuses responded to the survey (83.3% response rate). Thirty satellite campuses out of 40 responded to the survey (75% response rate). Results presented are based on a denominator of 40 satellite campuses and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structure of Satellite Campuses and Student Organizations (n=30 satellite campuses)

Seventeen (56.7%) satellite campuses delivered all four years of education on the satellite campus (parallel program), whereas eight (26.7%) campuses described themselves as a 2+2 program or sequential campus (two years on the main campus followed by two years on the satellite campus). The structure of one school (3.3%) included one year on the main campus followed by three years on the satellite campus.

The mean number of students per class on satellite campuses was 48.4 (33) (range 11-150 students). Satellite campuses were located a mean of 240 (287) miles away from their main campus (range 44 – 1186 miles), and approximately half were within 100 miles of the main campus. Twenty-four satellite campuses (75%) were established after 2000, one was established in the 1990s (3.5%), and two satellite campuses were developed in the 1970s (7.0%). The most common title for the satellite campus leader was associate dean (40.0%) or assistant dean (36.7%). Twenty-six of the satellite campus leaders worked primarily on the distance campus (93.3%) (Table 1).

The structure of student organizations on satellite campuses is described in Table 1. The most frequently mentioned student organizations included APhA (27 satellite campuses, 93.1%), ASHP (26 satellite campuses, 89.7%), CPFI (18 satellite campuses, 60.0%), local organizations (17 satellite campuses, 58.6%), and the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) (12 satellite campuses, 40.0%). The Student National Pharmaceutical Association (SNPhA) and the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists (ASCP) were available at fewer campuses (23.3% and 26.7%, respectively). Professional fraternities on satellite campuses included Kappa Psi (70.0%), Kappa Epsilon (46.7%), and Phi Delta Chi (50.0%). Students communicated across campuses about student organizations through video-teleconferencing (90.0%), e-mail (80.0%), telephone (56.7%), and travel to the main campus (60.0%).

Student governance for 76.7% of student organizations on satellite campuses was shared with the main campus, whereas 46.7% of organization governance was provided solely by satellite campus students). One third of satellite campuses maintained student governance on the main campus for some student organizations. Forty-six percent of respondents reported that their school of pharmacy offered student organizations on the main campus, which were not offered on the satellite campus.

All satellite campuses offered faculty and staff support for student organizations. Advisors for student organizations were located on or near the satellite campus (83.3%), or on or near the main campus (40.0%). Travel reimbursement and financial support of organizations were offered to students by 66.7% and 63.3% of satellite campuses, respectively. Eighty-nine percent of satellite campuses reported that their student organizations provided service projects for the community, and 50% of campuses continued to offer students leadership opportunities in student organizations during advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs). Forty-three percent of satellite campuses offered leadership training for student leaders.

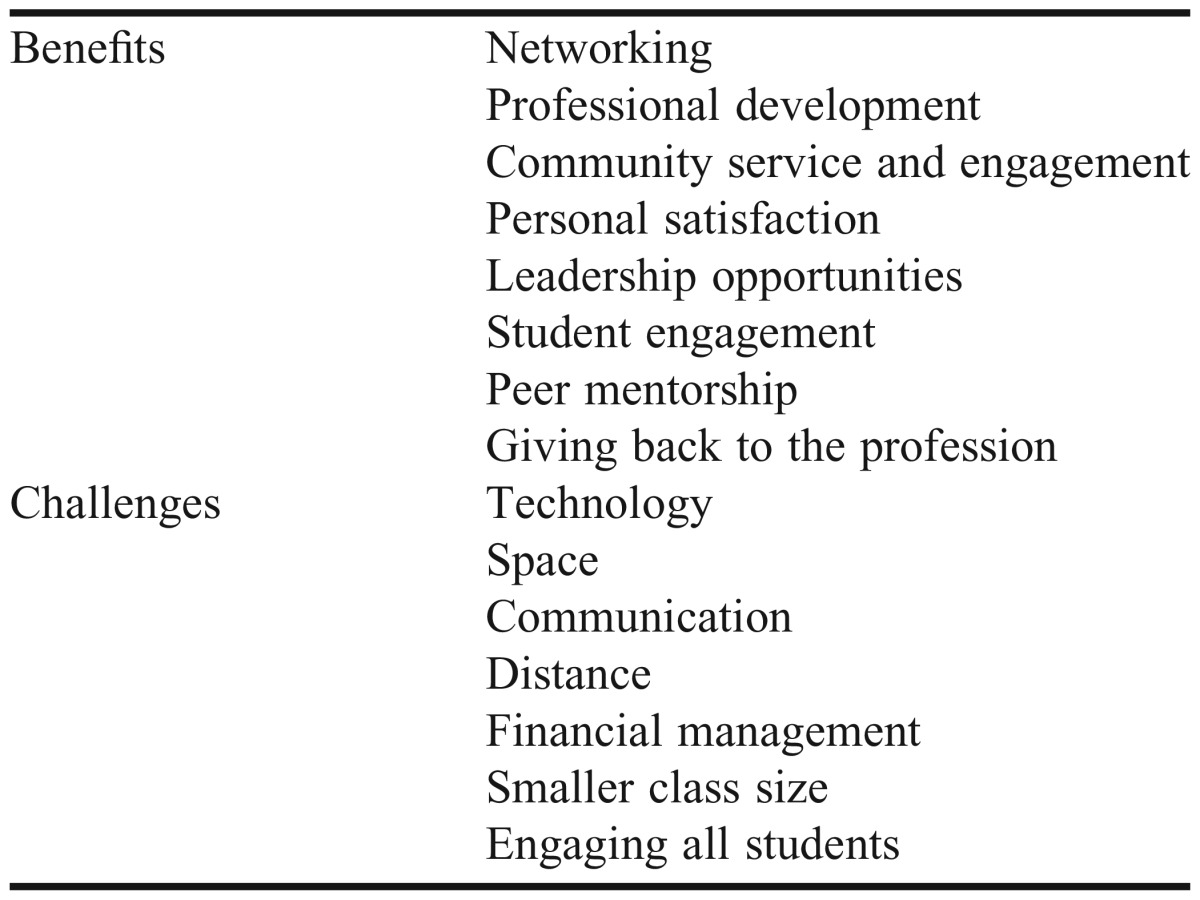

Because perceived benefits and challenges associated with student organizations were assessed using open-ended questions, it was not possible to fully quantify the responses. However, general themes associated with perceived benefits of student organizations on satellite campuses included opportunities for networking and professional development, promotion of service and community engagement, development of professionalism, and the chance to connect with students residing on the main campus. Forty percent of respondents cited leadership development as the most important benefit of student organizations. (Table 2). Two respondents noted that smaller enrollment on satellite campuses resulted in more leadership opportunities for students. General themes associated with perceived barriers to success of student organizations on satellite campuses included the need for a critical mass of students to operationalize an organization, lack of communication with students on other campuses, managing funds and making purchases, and the need for travel and housing for events across campuses. Thirty percent of respondents to the open-ended question about challenges of student organizations on satellite campuses noted smaller enrollment numbers and the need for technology as challenges. Moreover, 22% of respondents commented that students on satellite campuses may feel disconnected from organizational events happening on the main campus (Table 2).

Table 2.

Qualitative Perceived Benefits and Challenges Associated with Student Organizations on Satellite Campuses

DISCUSSION

Cocurricular activities for doctor of pharmacy students are an important component of the student experience and help foster professionalism and relationship-building.7,8 Moreover, student organizations are an important component of the student experience, according to the ACPE Standards.10 Specifically, Standard 4 focuses on personal and professional development with emphasis on four key elements: self-awareness, leadership, innovation and entrepreneurship, and professionalism.10 Pharmacy student organizations create opportunities for students to engage with communities through service projects and volunteerism and to enhance professional development through patient care projects, clinical competitions, and seminars. For example, APhA sponsors national patient care projects for student pharmacists such as Operation Diabetes and professional development programs including the National Patient Counseling Competition. The ASHP has a Pharmacy Student Forum, and also hosts the annual Clinical Skills Competition. In this survey, APhA and ASHP were the most common student organizations on satellite campuses and were available to students on the vast majority of satellite campuses. Almost 90% of satellite campuses completed service projects, indicating that student pharmacists on distant campuses were engaging with their local communities.

Our survey indicated that faculty members on satellite campuses perceive that student organizations promote professionalism and leadership development. Several respondents noted that students on satellite campuses have significant opportunities to lead because of the smaller numbers of students available to serve in such roles. Poirier and Gupchup used a professionalism instrument developed by Chisholm to evaluate changes in professionalism across the curriculum among pharmacy students in different classes.7 First-year, second-year, and fourth-year responded to the instrument, which measured overall professionalism scores as well as subscales in excellence, respect for others, altruism, duty, accountability, and honor/integrity. Professionalism scores increased and demonstrated that curricular and cocurricular activities in the school of pharmacy contributed to the development of professionalism.7 Specifically, subscales in altruism, accountability, and honor/integrity increased after participation in service learning and student organizational events.7 Kiersma et al surveyed 514 students at Purdue University about their perceptions of the value of student organizations for their professional development.8 Students indicated that extracurricular activities improved their personal skill development including their abilities to take personal responsibility, help others, get along well with others, organize work and projects, and understand others’ point of view, but were less likely to help them with budgeting, policy development, or written communication.8 This body of literature indicates the important role that professional organizations play in the development of professionalism and leadership skills.

Our project indicated that satellite campus students were frequently involved in local organizations that were unique to their particular campus, which supports Congdon et al’s findings from the University of Maryland that described the development of student organizations on their satellite campus.11 They reported that 33% of students in the inaugural class on their distance campus participated in at least one organization on the main campus, whereas 97% of satellite students joined a locally developed organization called the DC Metro Student Pharmacist Association.11 This organization was developed by satellite students in order to create opportunities for professional development on a local level.11 The University of Missouri-Kansas City published a descriptive report about their experiences with student organizations on their satellite campus. When their satellite campus was opened in 2005, APhA was the first organization offered to satellite students and originated from the main campus. Authors noted that students on the satellite campus were not participating in events and postulated that student organizations based only on the main campus served as a barrier. Once an APhA student chapter with leadership positions was developed on the distance campus, student satisfaction with leadership, social, and volunteer opportunities increased.9 Thus, students on satellite campuses may be more likely to engage in student organizations that include activities that are locally focused.

Adams et al evaluated the student organizational experience from four schools with satellite campuses.12 Each school offered parallel campuses, meaning that all four years of study occurred on the main campus or the satellite campus. Thirty-one percent of the 1013 students who were surveyed responded. Ninety-three percent of students on the main campus participated in student organizations, and 92% of satellite campus students participated. However, only 80% of students on satellite campuses were satisfied with access to faculty advisors for student organizations compared to 93% satisfaction among main campus students. Fewer students on satellite campuses than on main campuses felt that it was easy to communicate between campuses (37% vs 49%), or felt a sense of belonging with their classmates on the other campus (47% vs 58%).12 Despite the fact that the survey indicated most faculty advisors were located on or near the satellite campus, students at the satellite campus may not have perceived adequate support from advisors.

Satellite campuses have unique needs not simply associated with the delivery of the academic experience associated with coursework, active learning, and examinations. Satellite campuses also face challenges with ensuring that cocurricular activities are rich and thriving and that the experiences are equivalent to those of main campus students. Specific areas of concern about satellite campus student organizations addressed in the literature include technology, scheduling, culture, resources, and communication.2,6 Our survey indicates that these challenges continue to be an area of concern on satellite campuses. However, there are some untested practicalities that might prevent problems and promote school unity. Using video-technology for student organization meetings can bridge the distance gap, though simply attaching the satellite campus report onto the end of a meeting agenda could create a sense of disconnection. It is important for student leaders to decide what information needs to be shared and discussed with the entire student organization via video-technology and what information is best discussed locally in order to develop trusting relationships and conduct efficient meetings. Time during meetings should be allocated for discussing activities on all campuses instead of solely focusing on the main campus. Reserving the appropriate rooms for meetings in advance and connecting by videoconference before the meeting may help ensure important meeting time is not wasted on such logistics. Financial support for student organizations should be discussed at the beginning of each academic year with student leaders and advisors to ensure transparency and fair allocation of resources across campuses. Faculty advisors should be accessible to student leaders and members during organizational planning and events. Finally, student leaders and advisors alike set the tone and contribute to the culture on campus, and it is important for everyone to be committed to the vision, mission, and values of their respective student organizations.

Coupled with prior research, our findings provide support for the following recommendations regarding student organizations on satellite campuses: (1) Because student organizations are an important component of the student experience and contribute to the development of professional behaviors,7 a culture of support for student organizations and advisor engagement should be a cornerstone of satellite campus life; (2) Because a critical mass of students is necessary to operationalize student organizations on a satellite campus, it is important to focus on excellence within individual organizations as opposed to creating a multitude of organizations that might not succeed; (3) To promote unity within the entire student body while also making an impact on individual campus communities, schools should provide a mixture of student organizations that collaborate across campuses and initiatives that focus on the unique needs of each campus community;9,11 (4) Leadership training and advisor support that emphasizes effective communication and relationship building at one school of pharmacy on multiple campuses is important.

There are several limitations to this study. We did not compare differences in student organizations on satellite campuses with a small student body with those of a larger student body. We were not able to determine the critical mass of students necessary to build a successful student organization; however, Kappa Epsilon’s bylaws require a minimum of 10 students to begin a colony. Finally, it is not known which benefits and challenges of student organizations are most important and which ones matter least to students. Future studies focused on student organizations on satellite campuses should examine these issues in more detail.

CONCLUSION

A growing number of schools of pharmacy have satellite campuses, most being established in the last 15 years. Because satellite campuses tend to have smaller numbers of students and are located away from the main campus, development of student organizations is associated with unique challenges. Despite this, satellite campuses had student organizations in place and almost all campuses provided service projects within their communities. Resources were available on satellite campuses to support student organizations including advisors, space, travel reimbursement, and financial support. Most student organizations were governed on the satellite campus or across campuses. Although communication among students on different campuses frequently utilized video-technology, visits to other campuses were also frequent. Primary administrators on satellite campuses recognized the benefit student organizations play in the professional development of students. Students on satellite campuses appear to have significant opportunities for leadership development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Laura Bratsch and Jennifer Marvin for their assistance with the manuscript.

Appendix 1. Schools of Pharmacy with Satellite Campuses in 2013

Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences

Auburn University

Ferris State

Florida Agriculture and Mechanical University

Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine School of Pharmacy

Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences

Nova Southeastern

Oregon State University

Roseman School of Pharmacy

Shenandoah University

South University

Texas Tech

University of Arkansas

University of Florida

University of Georgia

University of Idaho

University of Illinois, Chicago

University of Kansas

University of Maryland

University of Minnesota

University of Mississippi

University of Missouri, Kansas City

University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy

University of Oklahoma

University of South Dakota

University of Tennessee

University of Texas-Austin

Virginia Commonwealth University

Washington State University

Wingate University

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Preaccredited and accredited professional programs of colleges and schools of pharmacy. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/shared_info/programsSecure.asp. Accessed August 29, 2014.

- 2.Harrison LC, Congdon HB, DiPiro JT. The status of US multi-campus colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(7):Article 124. doi: 10.5688/aj7407124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Association of Medical Schools. Group on Regional Medical Campuses. https://www.aamc.org/members/grmc/. Accessed 7/1/2015.

- 4.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503–509. doi: 10.1370/afm.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheifetz CE, McOwen KS, Gagne P, Wong JL. Regional medical campuses: a new classification system. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1140–1143. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox BI, McDonough SL, McConatha BJ, Marlowe KF. Establishing and maintaining a satellite campus connected by synchronous video conferencing. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(5):Article 91. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poirier TI, Gupchup GV. Assessment of pharmacy student professionalism across a curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(4):Article 62. doi: 10.5688/aj740462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiersma ME, Plake KS, Mason HL. Relationship between admission data and pharmacy student involvement in extracurricular activities. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(8):Article 155. doi: 10.5688/ajpe758155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vyas D, Stinner N, Lindsey C. Promoting the professional development of students through the creation of a student organization on a satellite campus. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(5):580. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.09060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 11.Congdon HB, Nutter DA, Charneski L, Butko P. Impact of hybrid delivery of education on student academic performance and the student experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(7):Article 121. doi: 10.5688/aj7307121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams EN, Conry JM, Heaton PC, et al. Student pharmacists’ perceptions of access to student organization opportunities at colleges/schools of pharmacy with satellite campuses. Curr Pharm Teach and Learn. 2015;7(2):185–191. [Google Scholar]