Abstract

Objective. To compare United States and European Higher Education Area (EHEA) undergraduate pharmacy curricula in terms of patient-centered care courses.

Methods. Websites from all pharmacy colleges or schools in the United States and the 41 countries in the EHEA were retrieved from the FIP Official World List of Pharmacy Schools and investigated. A random sample of schools was selected and, based on analyses of course descriptions from syllabi, each course was classified into the following categories: social/behavioral/administrative pharmacy sciences, clinical sciences, experiential, or other/basic sciences.

Results. Of 147 schools of pharmacy, 59 were included (23 in US and 36 in the EHEA). Differences existed in the percentages of credits/hours in all of the four subject area categories.

Conclusion. Institutions in EHEA countries maintain a greater focus on basic sciences and a lower load of clinical sciences in pharmacy curricula compared to the United States. These differences may not be in accordance with international recommendations to educate future pharmacists focused on patient care.

Keywords: Education, pharmacy, patient-centered, curriculum, United States, Europe

INTRODUCTION

The global pharmacy profession has shifted from a product oriented to a patient-centered practice.1 Consequently, pharmacy education is adapting to this paradigm.2,3 The movement toward clinical education in pharmacy curricula has been discussed in the United States for a long time.4 International organizations have delivered statements and positions to guide this movement. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended an appropriate balance of the following components in curricula: basic sciences, including pharmaceutical and biomedical sciences, and clinical sciences, socioeconomic and behavioral sciences, and practical experience. Moreover, WHO stressed that courses related to the implementation of patient-centered care (eg, communication skills) should be introduced.5,6 The International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) supports pharmacy education improvement while emphasizing clinical education and the importance of patient-centered care curricula.7

Some countries have adapted their curricula to face the changes in the pharmacy profession as it moves toward clinical and patient care.8,9 Other countries have focused efforts on improving areas of pharmacy curricula, such as clinical pharmacy10-12 and the social and behavioral sciences.13-16 In the United States, the change in pharmaceutical education was marked by the creation of the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) as the sole degree required to enter practice.17,18 The US-based Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards and guidelines have been adapted to address the patient-centered practice requirements.19 Curriculum reform has increased disciplines oriented toward providing clinical experiential models and has improved the competencies related to evidence-based practice and patient-centered care, whether in community or institutional pharmacy practice.20,21

European Union (EU) treaties support the mobility of professionals across Europe without requiring further training or diploma validation, meaning that a degree obtained in one EU member country is valid across the European Union. With the aim of creating a harmonized European Higher Education Area (EHEA), in June 1999, European ministers of education signed the Bologna Declaration. A system of easily comparable degrees was adopted among EU countries.22 To date, 47 EU countries have adopted the Bologna Declaration.23 A consequence of the Bologna process was EU legislation that dictated definitions of the knowledge, skills, and core competencies that undergraduate education should provide to students seeking to become pharmacists.24 The pharmacy degree had to adapt to a structure based on a 2-cycle (ie, bachelor and master) degree system with at least five years of study corresponding to 300 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS). This training includes at least four years of full-time theoretical and practical training administered at a university or a recognized equivalent institute, and at least six months of university-supervised practical training through a rotation between a community pharmacy and a hospital (with a mandatory 4-month period in community pharmacy).24,25 In line with the Bologna Declaration, the majority of EHEA countries changed their pharmacy curricula,26,27 but it is not clear whether these modifications have led the European curricula to be more patient-centered. Thus, our aim was to analyze and compare course contents of US and EHEA undergraduate pharmacy curricula to determine the amount of patient-centered care courses.

METHODS

Lists of schools of pharmacy in the United States and the EHEA were extracted from the FIP Official World List of Pharmacy Schools.28 Small errors, such as duplicate data and schools that did not provide entry-level degrees for the profession, were removed from the list. The websites of all pharmacy schools in these two regions were located and analyzed. To be eligible for the study, the institutions had to meet the following criteria: a website in English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese or Spanish; a complete curriculum for the academic year 2013-2014 on the website; the hours or credits per course in the curriculum; a syllabus of all courses available on the website (as a tolerance criterion, a lack of up to five syllabi was allowed); and an internship (pharmacy practice experiences) integrated into the curriculum.

To obtain a representative sample of the pharmacy education institutions per country, randomized selection was performed via the generation of a list of random numbers. Twenty-five percent of the schools from each country, with a minimum of four institutions per country, were selected. For countries with fewer than four pharmacy education institutions meeting the criteria, all schools were included in the sample. The syllabi for all of the courses from the selected schools in the sample were downloaded. Elective courses were excluded from the analysis.

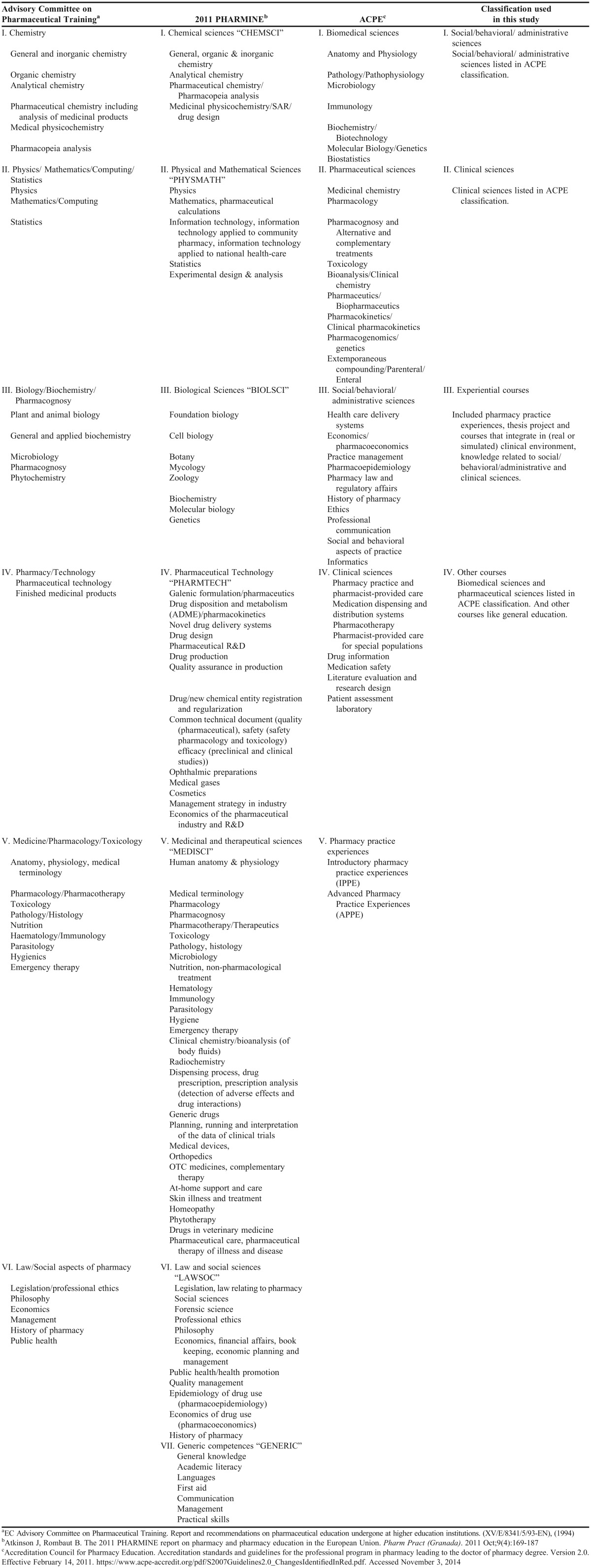

To analyze the course contents in the syllabi, we created a guidance for data extraction and classification. Based on the “Curricular Core – Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, and Values” section of ACPE’s Standards,19 we created a 4-area categorization system. Social/behavioral/administrative pharmacy sciences included health care delivery systems, economics/pharmacoeconomics, practice management, pharmacoepidemiology, pharmacy law and regulatory affairs, history of pharmacy, ethics, professional communication, social and behavioral aspects of practice, and informatics. Clinical sciences included pharmacy practice and pharmacist-provided care, medication dispensing and distribution systems, pharmacotherapy, pharmacist-provided care for special populations, drug information, medication safety, literature evaluation and research design, and patient assessment laboratory. Experiential courses included pharmacy practice experiences, thesis projects, courses that combined (real or simulated) clinical environments, knowledge related to social/behavioral/administrative pharmacy sciences, and clinical sciences. Finally, other/basic sciences included biomedical sciences, pharmaceutical sciences, and other courses, including general education courses (ie, subjects outside pharmacy area).

When the contents of a course described in the syllabi could fit into more than one category, we classified that course in the more appropriate category based on the majority of the topics in the course description. The unit of course loads provided in the institution’s website, such as credits/hours, credits, or hours, were extracted. Elective courses were not considered, but the number of credits/hours, credits, or hours required from elective courses were computed for the overall total. The accumulated load of credits/hours, credits, or hours dedicated to each subject area were calculated. Three of the four areas were considered patient-centered care: clinical sciences, social/behavioral/administrative sciences, and experiential.

The data were extracted by one researcher. To ensure the utility of the guidance for extraction and the internal validity of the study, a randomized sample of 25% of the selected educational institutions was extracted by a second researcher. The interrater agreement was estimated by calculating the Cohen kappa coefficient.29 Disagreements were analyzed by a third researcher to determine whether the guidance for data extraction needed to be refined.

For an overall comparison of the countries from these two regions with different course-credit systems, we created a scoring method. First, we calculated the mean percentages of credit/hours in each area among the schools in each country. For the three patient-centered care areas (clinical, social, and experiential), countries were ordered according to the mean percentages of credit/hours from highest to lowest, and each country was attributed a score that corresponded to its rank order in each of these three lists (18 points to the highest number of credit/hours in each of the three categories). Conversely, countries were ordered lowest to highest (inverted order) according to their mean percentage of credit/hours from basic sciences, and the score attributed corresponded to this inverted order (18 points to the lowest number credit/hours in basic sciences). Thus, the maximum (ie, the best) score possible was 72 points (18 points x 4 areas), and the minimum (ie, the worst) score possible was 4 points (1 point x 4 areas).

To assess the interrater agreement regarding the validation of the extraction method, Cohen kappa coefficients were used.29 Kappa values from 0.61 to 0.80 were associated with “substantial agreement”, and kappa values over 0.80 were associated with “almost perfect agreement.”30 To test the assumptions of the normal distributions of the study data, Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality tests were performed. The data were analyzed using nonparametric methods. Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare the means of two independent populations. Finally, a model for predicting the geographical origin (ie, United States or EHEA) of the schools was created using logistic regression on the percentages of the credits/hours of the three patient-centered care areas as covariates. For all of the analyses, a level of 5% was considered significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS, v20 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Websites of the 364 schools of pharmacy that appeared in the FIP Official World List of Pharmacy Schools,28 including 121 from the United States and 243 from the 41 EHEA countries, were considered for the study. Institutions were excluded if they lacked: a website in English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, or Spanish (n=62); a complete curriculum for the activity in the academic year 2013-2014 available on the website (n=14); hours or credits per course (n=51); a syllabus of all of the courses available on the website (n=78); and internship (pharmacy practice experience) in the curriculum (n=11).

Of the 148 potential schools, 59 were randomly selected for the analysis (23 from the United States and 36 from the 17 EHEA countries) (Table 1). In the validation phase, 25% of the 59 schools selected for the sample were independently analyzed by two authors (six from the EHEA countries and nine from the US), which resulted in an interrater agreement with a Cohen kappa = 0.91. The kappa coefficient for the six EHEA schools of pharmacy was 0.94 and for the nine US schools, 0.91; both of these values were considered almost perfect agreements.

Table 1.

Pharmacy Colleges in the United States and European Higher Education Area

Comparisons of the US and EHEA schools revealed no difference in the percentages of credits/hours for elective courses (p=0.43; US=7.1%, SD=3.8; EHEA=6.4%, SD=4.2). However, differences were identified in the percentages of credits/hours dedicated to each of the four subject area categories: social/behavioral/administrative pharmacy sciences (p=0.038, US=7.8%, SD=2.6; EHEA=6.0%, SD=3.0), clinical sciences (p<0.001, US=16.7%, SD=5.0; EHEA=4.1%, SD=3.2), experiential courses (p<0.001, US=26.4%, SD=4.8; EHEA=17.9%, SD=7.0), and other/basic sciences (p<0.001; US=49.0%, SD=5.0; EHEA=72.0%, SD=8.9).

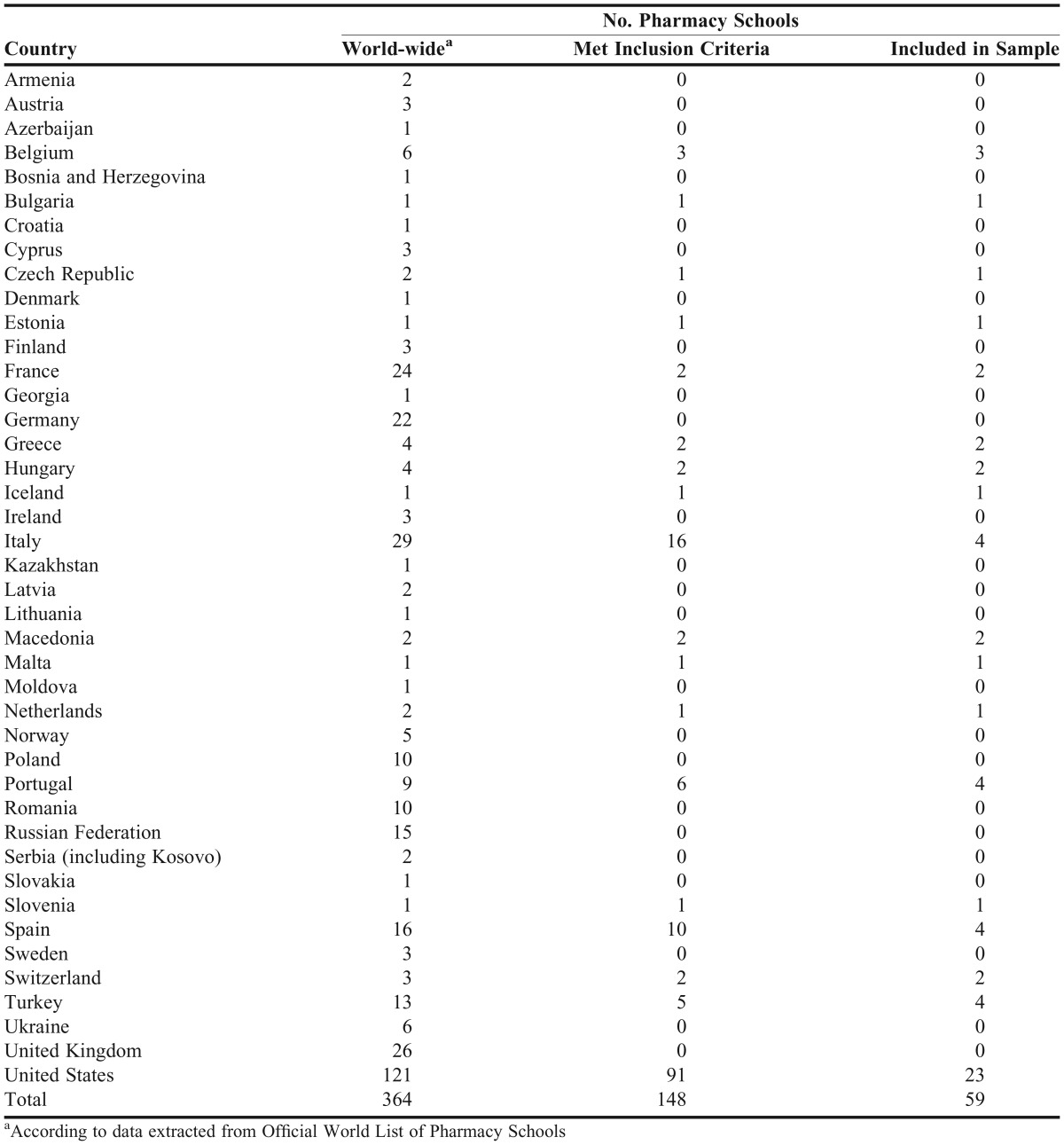

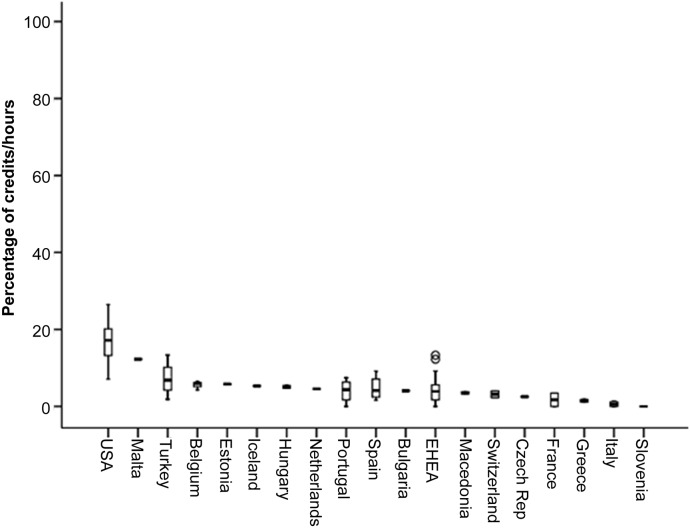

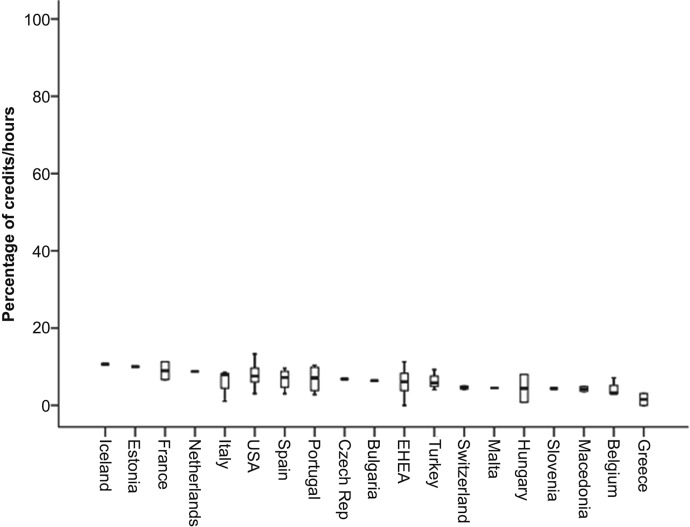

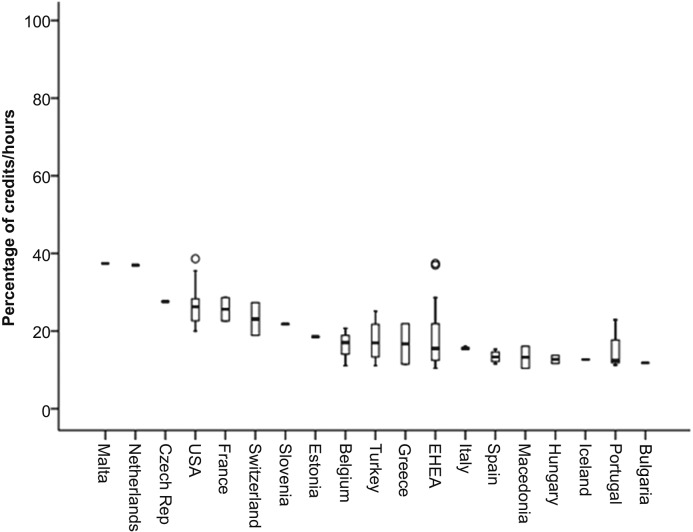

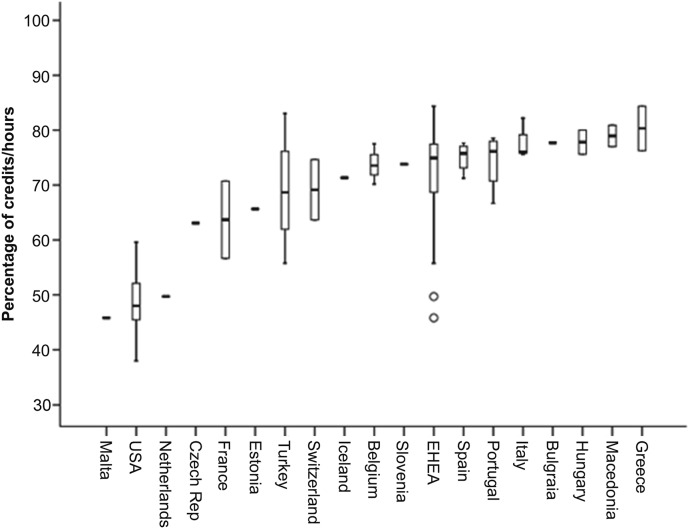

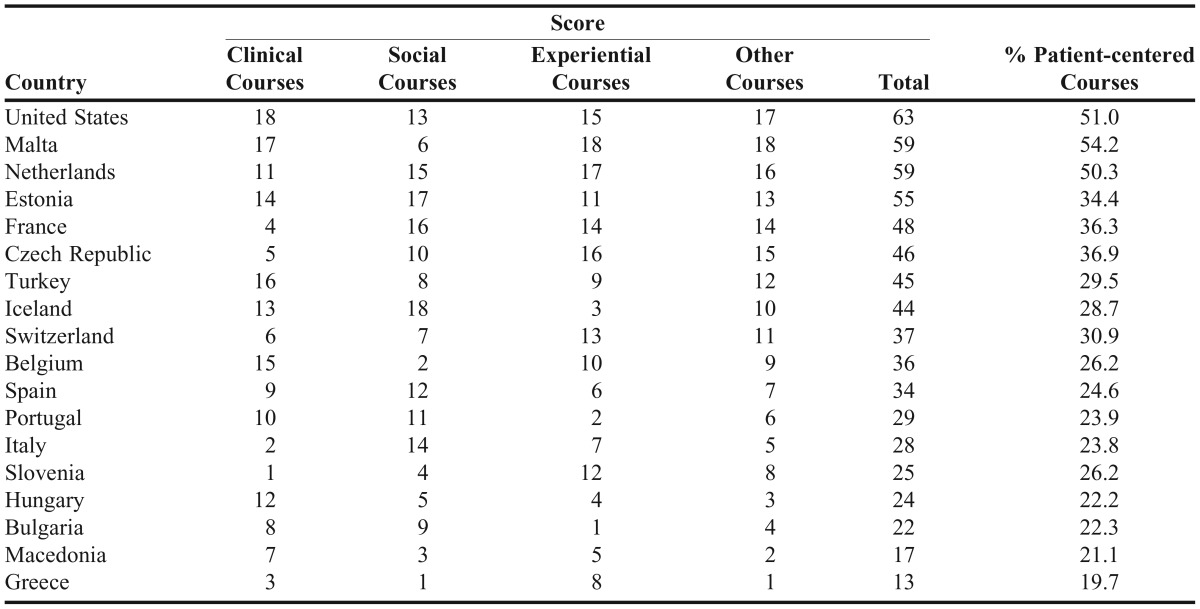

The curriculum with the highest mean percentage of clinical sciences was that of the United States at 16.7% (SD=5.0) followed by Malta at 12.3% (SD=0). The clinical sciences courses were elective courses in the curricula of Slovenia (Figure 1). Iceland had the curriculum with the highest mean percentage content in social/behavioral/administrative pharmacy sciences at 10.7% (SD=0), and Greece had the curriculum with the lowest, with only 1.5% (SD=2.2, Figure 2). Figure 3 shows that Malta exhibited the highest percentage of experiential courses at 37.4% (SD=0) and that Bulgaria exhibited the lowest percentage of 11.8% (SD=0). Greece, with 80.3% (SD=5.7), was the country with the highest percentage of basic sciences, such as basic biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences. Malta and the United States were the countries with the lowest mean percentages of basic sciences with 45.8% (SD=0) and 49.0% (SD=5.0), respectively (Figure 4). The United States had the curriculum with the best score of 63 of the 72 possible points followed by Malta and the Netherlands, which each had 59 points. The percentages of schools with patient-centered care foci were also calculated (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Percentage of credits/hours for clinical sciences out of the total credit/hours of mandatory courses (box-plot: boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR); error lines represent +/− 1.5 times the IQR; circles represent outliers).

Figure 2.

Percentage of credits/hours for social/behavioral/administrative pharmacy sciences out of the total credit/hours of mandatory courses (box-plot: boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR); error lines represent +/− 1.5 times the IQR; circles represent outliers).

Figure 3.

Percentage of credits/hours for experiential courses out of the total credit/hours of mandatory courses (box-plot: boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR); error lines represent +/− 1.5 times the IQR; circles represent outliers).

Figure 4.

Percentage of credits/hours for other course (basic biomedical sciences, basic pharmaceutical sciences and others) out of the total credit/hours of mandatory courses (box-plot: boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR); error lines represent +/− 1.5 times the IQR; circles represent outliers).

Table 2.

Score of the Pharmacy Curriculum and Percentage of Patient-centered Courses in the Curriculum

In multivariate analysis of the percentages of the three patient-focused areas, we created a model (Nagelkerke R squared=0.89) to predict the geographical origin of each school and found that only the percentage of clinical sciences was significant (p=0.010) with an OR=1.2 (95% IC =1.2 – 3.6) (Hosmer and Lemeshow test p=0.99).

DISCUSSION

We compared curricula by analyzing course content of syllabi as the information source. Syllabi content analysis enabled the assessment of what topics were covered in each course. Therefore, this analysis enables course categorization and curriculum comparisons.31,32 Because courses can have different names across countries, and to allow for comparisons of the curricula of different countries, courses were grouped into subject areas. Our study exhibited two strengths: (1) the creation of guidance for data extraction, which resulted in a high concordance as indicated by the high interrater agreement, and (2) the subject areas were based on known standards19 created to define modern pharmacy curricula. Other studies have compared pharmacy curricula across EU member countries and grouped courses for pharmacy degrees into different subject areas (Appendix 1).33-35 However, two limitations were present in these studies: the allocation of each course to a subject area seems to have been based on the course names and not on course content analysis and the subject areas were based on the traditional areas of education for pharmacists, more associated with basic sciences, that existed prior to the clinical movement.

According to the 1994 report of the Advisory Committee on Pharmaceutical Training, “chemical subjects” account for more required course hours in the range of 25%-46% across European countries. Physics/mathematics/computing/statistics (3%-13%) and social aspects of pharmacy/law (1%-16%) are subject areas minimally focused on in European curricula. Prior to the implementation of the Bologna Declaration, undergraduate pharmacy programs varied significantly in length among European countries, and large differences in the distributions of the total numbers of hours of required courses by subject area were present.33 In the 2011 PHARMINE report, “medical sciences” represented the main subject area in pharmacy education in the European Union (28%).34,35 However, this finding could be misleading because the “medical sciences” subject area included a mix of courses, such as human anatomy and physiology, pharmacology, parasitology, dispensing processes, prescription analysis, and pharmaceutical care. Based on the ACPE course categorization, some of these courses belonged to the clinical sciences, and others belonged to the biomedical/basic sciences (eg, anatomy and physiology) or pharmaceutical sciences (eg, pharmacology, Appendix 1). A recent article compared these two stages of European pharmacy curricula and reported a decrease in the number of hours related to the chemical sciences (from 33% to 26%) and an increase in the number of hours related to the medical sciences (from 19% to 28%). It seems that changes in European curricula increased the load of clinical courses and that pharmacy education is in line with international recommendations.36 However, our results revealed that the European curricula were still focused primarily on basic sciences.

Comparison of the US and EHEA curricula revealed significant differences in all four of the subject areas. In a bivariate analysis, the loads of the three patient-centered care areas were found to be significantly higher in the United States than in the EHEA, while the other/basic sciences were significantly more predominant in the EHEA countries. This resulted in the United States having the highest score of 63 points (out of 72) followed by two countries that had 59 points each (Malta and the Netherlands). In a multivariate analysis, the significant difference appeared to be associated with the higher clinical sciences course load in the United States.

Our results are in line with those of Kostriba et al, who reported a reduced focus on social pharmacy courses in Europe compared with North America. Twenty-six percent of European curricula and 6% of US and Canadian schools lacked pharmacy management courses, and 47% of European schools lacked an education and research methods course.37 The focus on clinical aspects in the United States is also confirmed by studies that compare US curricula to those of New Zealand and China.38,39

The FIP and WHO are attempting to improve the quality of pharmacy curricula via competency-based education.40-43 Although the definition of a competency framework is important, it may not be sufficient. To achieve the new required professional competencies, disciplines and course contents have to be adapted to patient-centered care practice.19 Some authors support the revisions of European pharmacy curricula that followed the Bologna Declaration because these revisions intended to emphasize clinical skills to prepare pharmacists to practice effectively in a changing paradigm.10,44-46 Our study demonstrated that there is room to refocus curricula toward more patient-centered practices. To achieve this goal, the limited clinical sciences load must be addressed. Following international recommendations, a reduction in the basic sciences courses load associated with an increase in clinical sciences courses could be a potential solution to refocus European pharmacy curricula.7,36

One potential limitation of our study is that we excluded 62 (of the 243) EHEA schools of pharmacy because their websites were not a language spoken by the authors. However, these schools might have been excluded for other reasons (ie, not providing a complete syllabus). Additionally, as professionals’ mobility is only ensured across EU countries, after excluding criteria our study covered schools from 13 of the 23 EU members, but covering a population of more than 72% of the roughly 353 million people in EU elective countries.47 In our study, we excluded elective courses because we intended to establish the profiles of any graduated pharmacist regardless of the elective courses studied. We also underestimated the differences between the United States and EHEA countries regarding the experiential courses because we considered only countries that included internship periods in the university curriculum. Countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Austria were excluded because they have the European mandatory 6-month practical training25 outside of university supervision.

CONCLUSION

Despite curriculum revisions that have been completed in EHEA countries following the Bologna Declaration, European pharmacy education has a higher basic science course load and a lower patient-care centered course load than US pharmacy curricula. Although differences also exist in the social/administrative sciences and experiential courses, the main differences between the US and EHEA curricula involve the clinical sciences (16% in United States vs 4% in EHEA) and the basic sciences (49% in United States vs 72% in EHEA). The use of different subject group categories may have led to erroneous interpretations of the EHEA curriculum revision. European countries should consider revisiting their curricula if they want to meet WHO and FIP recommendations.5-7

Appendix 1. Pharmacy Degree Courses Grouped in Subject Areas

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson S. The state of the world’s pharmacy: a portrait of the pharmacy profession. J Interprof Care. 2002;16(4):391–404. doi: 10.1080/1356182021000008337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Mil JW, Schulz M, Tromp TF. Pharmaceutical care, European developments in concepts, implementation, teaching, and research: a review. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26(6):303–311. doi: 10.1007/s11096-004-2849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toklu HZ, Hussain A. The changing face of pharmacy practice and the need for a new model of pharmacy education. J Young Pharm. 2013;5(2):38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jyp.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hepler CD. The third wave in pharmaceutical education: the clinical movement. Am J Pharm Educ. 1987;51(4):369–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The role of the pharmacist in the health care system. Report of a WHO consultative group, New Delhi, India, 1988. Report of a WHO meeting, Tokyo, Japan, 1993 (WHO/PHARM/94.569). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994.

- 6. The role of the pharmacist in the health care system. Preparing the future pharmacist: curricular development. Report of the third WHO consultative group on the role of the pharmacist, Vancouver, Canada, 1997 (WHO/PHARM/97/599). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997.

- 7.International Pharmacy Federation. FIPEd Global Education Report. http://www.fip.org/files/fip/FIPEd_Global_Education_Report_2013.pdf. The Hague: FIP; 2013. Accessed October 18, 2014.

- 8.Marriott JL, Nation RL, Roller L, et al. Pharmacy education in the context of Australian practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article131. doi: 10.5688/aj7206131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin Z, Ensom MHH. Education of pharmacists in Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 128. doi: 10.5688/aj7206128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loennechen T, Lind R, Mckellar S, Hudson S. Clinical pharmacy curriculum development in Norway: pharmacists’ expectations in the context of current European developments. Pharm Educ. 2007;7(1):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan M, Shao H, Yang L, et al. Clinical pharmacy education in China. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 129. doi: 10.5688/aj7206129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youmans S, Ngassapa O, Chambuso M. Clinical pharmacy to meet the health needs of Tanzanians: education reform through partnership across continents (2008-2011) J Public Health Policy. 2012;33(Suppl 1):S110–S125. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2012.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan K, Bissell P, Anderson C, Traulsen JM, Sleath B. Teaching social sciences to undergraduate pharmacy students: an international survey. Pharm Educ. 2007;7:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Al-Haddad MS, et al. Social pharmacy as a field of study: the needs and challenges in global pharmacy education. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2011;7(4):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zorek JA, Lambert BL, Popovich NG. The 4-year evolution of a social and behavioral pharmacy course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(6):Article 119. doi: 10.5688/ajpe776119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alkhateeb FM, Latif DA, Adkins R. The economic, social and administrative pharmacy (ESAP) discipline in US schools and colleges of pharmacy. Int J Manag Econ Soc Sci. 2013;2(3):187–204. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education. Entry-level education in pharmacy: commitment to change. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57:366–374. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education. Background paper II: entry-level, curricular outcomes, curricular content and educational process. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57:377–385. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Version 2.0. Effective February 14, 2011. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/S2007Guidelines2.0_ChangesIdentifiedInRed.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2015.

- 20.Das NG, Das SK. An approach to pharmaceutics course development as the profession changes in the 21st century. Pharm Educ. 2001;1(3):159–171. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeind CS, Blagg JD, Jr., Amato MG, Jacobson S. Incorporation of Institute of Medicine competency recommendations within doctor of pharmacy curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(5):Article 83. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Bologna Declaration of 19 June 1999: joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6RvM9tImK. Accessed June 13, 2015.

- 23. Making the most of our potential: consolidating the European Higher Education Area. Bucharest Communiqué, 26–27 April 2012. http://www.ehea.info/Uploads/%281%29/Bucharest%20Communique%202012%281%29.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2015.

- 24. Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the recognition of professional qualifications (Text with EEA relevance). Off J Europ Union. L 255:22–142. https://www.medicalcouncil.ie/About-Us/Legislation/EU-Directive.pdf.

- 25. Directive 2013/55/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 amending Directive 2005/36/EC on the recognition of professional qualifications and Regulation (EU) No 1024/2012 on administrative cooperation through the Internal Market Information System (“the IMI Regulation”) Text with EEA relevance. Off J Europ Union. L 354:132–70.

- 26. Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad y Acreditación. [White Book on the Degree of Pharmacy] Madrid: ANECA; 2014.

- 27.Katajavuori N, Hakkarainen K, Kuosa T, Airaksinen M, Hirvonen J, Holm Y. Curriculum reform in Finnish pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 151. doi: 10.5688/aj7308151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Pharmaceutical Federation. Official world list of pharmacy schools. http://academic_institutional_membership.fip.org/world-list-of-pharmacy-schools/. Accessed September 16, 2013.

- 29.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohlen J, Furaker C, Jakobsson E, Bergh I, Hermansson E. Impact of the Bologna process in bachelor nursing programmes: the Swedish case. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(2):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermansson E, Martensson LB. The evolution of midwifery education at the master’s level: a study of Swedish midwifery education programmes after the implementation of the Bologna process. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(8):866–872. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. EC Advisory Committee on Pharmaceutical Training. Report and recommendations on pharmaceutical education undergone at higher-education institutions. (XV/E/8341/5/93-EN), (1994).

- 34. The PHARMINE WP7 survey. http://www.pharmine.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/WP7-Final-report-country-profiles.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2016.

- 35.Atkinson J, Rombaut B. The 2011 PHARMINE report on pharmacy and pharmacy education in the European Union. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2011;9(4):169–187. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552011000400001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atkinson J. Heterogeneity of Pharmacy Education in Europe. Pharm. 2014;2(3):231–243. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kostriba J, Alwarafi A, Vlcek J. Social pharmacy as a field of study in undergraduate pharmacy education. Indian J Pharm Educ. 2014;48(1):6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw JP. Undergraduate pharmacy education in the United States and New Zealand: towards a core curriculum? Pharm Educ. 2000;1(1):5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi ZM, Zhao RS, Zhai SD, et al. Comparison of US and Chinese pharmacy education programs. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(5):425–429. doi: 10.2146/ajhp130611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson C, Bates I, Beck D, et al. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce: enabling concerted and collective global action. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 127. doi: 10.5688/aj7206127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson C, Bates I, Beck D, et al. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruno A, Bates I, Brock T, Anderson C. Towards a global competency framework. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3):Article 56. doi: 10.5688/aj740356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.FIP Education (FIPEd) Initiative. FIPEd 5 years Action Plan 2014-2018. http://www.fip.org/pe_resources. Accessed March 29, 2015.

- 44.Antal I, Mátyus P, Marton S, Vincze Z. Developing the pharmacy curriculum in a Hungarian faculty. Pharm Educ. 2002;1(4):241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Popa A, Crisan O, Sandulescu R, Bojita M. Pharmaceutical care and pharmacy education in Romania. Pharm Educ. 2002;2(1):11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spinewine A, Dhillon S. Clinical pharmacy practice: Implications for pharmacy education in Belgium. Pharm Educ. 2002;2(2):75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 47.The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ Accessed June 13, 2015.