Abstract

Humans are altering the environment at an unprecedented rate. Although behavioural plasticity has allowed many species to respond by shifting their ranges to more favourable conditions, these rapid environmental changes may cause ‘evolutionary traps’, whereby animals mistakenly prefer resources that reduce their fitness. The role of evolutionary traps in influencing the fitness consequences of range shifts remains largely unexplored. Here, we review these interactions by considering how climate change may trigger maladaptive developmental pathways or increase the probability of animals encountering traps. We highlight how traps could selectively remove some phenotypes and compromise population persistence. We conclude by highlighting emerging areas of research that would improve our understanding of when interactions between evolutionary traps and range shifts are likely to be most detrimental to animals.

Keywords: fitness, habitat selection, dispersal, plasticity, HiREC

1. Introduction

Humans are changing the environment at faster rates than natural processes [1] and most animals now live in altered environments (e.g. [2]). Initially, animals are likely to respond behaviourally to rapid environmental change, allowing persistence in novel environments when those behaviours are beneficial [3]. Climate-driven range shifts, for example, allow animals to access resources that have been altered in their current range [4]. Alternatively, animals can shift the timing of life-history events (e.g. breeding, migration) to coincide with favourable conditions [4].

While some animals adapt to rapid environmental change, others respond inappropriately, compromising their fitness and persistence. Explaining this variability requires considering that: (i) behaviour is the outcome of cue-response systems, (ii) such systems are shaped by evolution and development, (iii) limited, imprecise and unreliable information probably causes suboptimal behaviour, and (iv) how animals ultimately respond to novel conditions depends on their degree of behavioural flexibility [1]. Although responses to imperfect information and behavioural flexibility may have been adaptive in past environments, maladaptive behaviours are likely to occur when animals encounter very different conditions from those that shaped their traits under previous selection [1,3].

Many animals use indirect cues to assess resources. If rapid environmental change creates a mismatch between cues and resource condition, ‘evolutionary traps’ can develop, when animals preferentially exploit resources where their fitness is reduced relative to other available alternatives [5]. Traps can affect habitat selection (‘ecological traps’), mate choice, oviposition, foraging and navigation [5]. While traps are behavioural phenomena, they may compromise population and metapopulation persistence [6,7]. Evolutionary traps and range shifts are likely to interact as animals increasingly move and experience novel conditions but this possibility has received limited attention. Here, we discuss some of the most likely interactions and their implications for animals, and propose future research avenues to improve understanding of when animals are most affected.

2. Phenotype/environment mismatches could increase encounters with evolutionary traps

Animals often respond to climate change by shifting their ranges [4], which depends on successful colonization and persistence in new areas. Climate change impacts are often considered in isolation, but could covary with other stressors (e.g. with land use conversion [8]) or even interact so that impacts on animals are compounded. Adaptive range shifts in response to changing abiotic conditions could be maladaptive in relation to other forms of change, such as when ground-nesting birds shift their distribution in relation to microclimate but suffer increased predation [9]. Range shifts could therefore increase the probability that animals dispersing throughout the landscape encounter traps, particularly when traps are prevalent in the landscape (e.g. [7]).

Critically endangered Kemp's ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys kempii) provide a useful example of this possibility [10]. Historically, this species nested in a sparsely populated section of the Mexican coast but the nesting population collapsed from tens of thousands to only several hundred females between 1947 and the mid-1980s as a result of commercial over-harvesting of eggs and fisheries by-catch of adults [11]. Considerable conservation efforts, especially protecting the nesting beach and reducing fisheries by-catch, were implemented and have led to a recovery of the breeding population [11]. A ‘headstarting’ programme was also implemented, with eggs moved to Padre Island in Texas [11,12].

Over the past 25 years, turtles have begun nesting in areas of Florida, potentially as overspill from the headstarting programme or via climate-mediated range expansion or a combination of both [10]. These turtles may be more likely to encounter ecological traps caused by humans (figure 1a, [10]). Recent modelling suggests that future range shifts in response to climate are predicted to result in turtles nesting in areas with lower human population density and thus potentially fewer ecological traps (figure 1a, [10]). However, if encounters with traps compromise the persistence of the Florida nesting population, these range shifts may not occur.

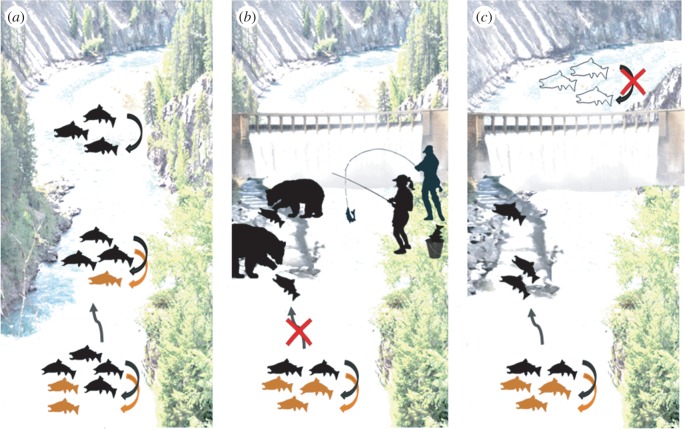

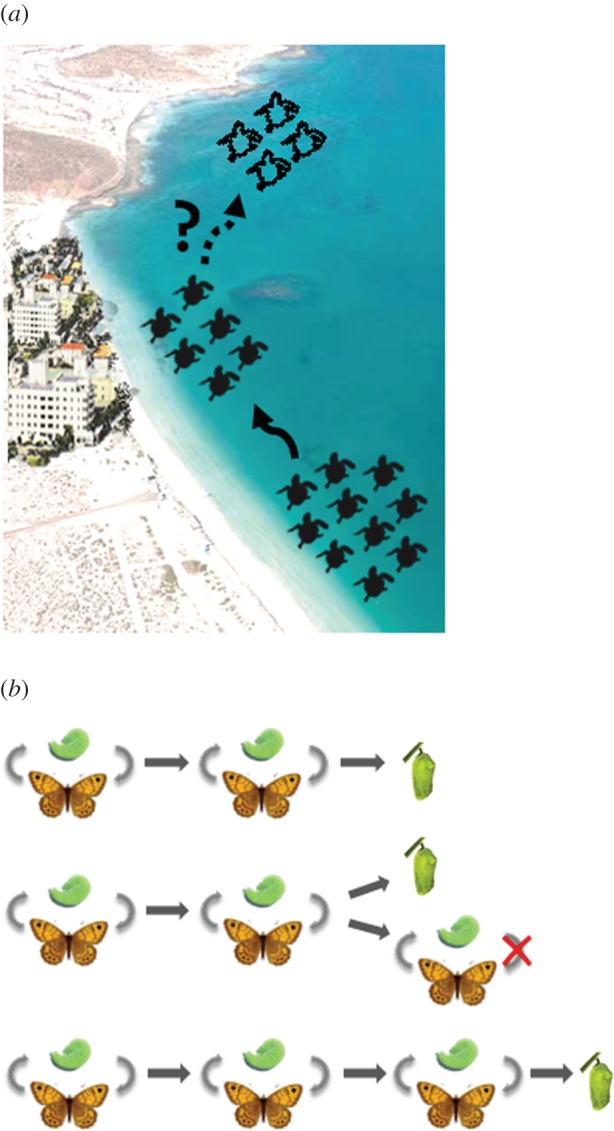

Figure 1.

Range shifts can change encounter rates with evolutionary traps. (a) The historical core range of the Kemp's ridley had low human population density, but a range shift (indicated by a solid black arrow) means turtles now inhabit areas with more humans and potentially more ecological traps [10]. Future climate-driven range shifts are predicted into areas with lower human population density but these may not occur if traps compromise populations in the current range (indicated by dotted arrow). (b) Maladaptive development in the wall brown butterfly (Lasiommata megera) [13]. This species completes two generations before larval diapause in the north and three generations in the south. A partial third generation can occur in sections of its range in years with warmer autumns. A developmental trap occurs when the season ends before the third generation is complete, causing mortality. Adapted from [13].

Range shifts also increase the probability of temporal phenotype/environment mismatches. Phenology has significant fitness consequences for animals, especially for those that use environmental cues to indicate suitable timing for behaviours such as breeding and migration (e.g. [14]). For many species, shifts in the timing of life-history events in response to environmental change have occurred so quickly that they almost certainly represent cases of behavioural plasticity rather than adaptation [15]. Not all species respond appropriately though, and the potential for traps to emerge in the context of climate change and phenology has recently been highlighted [16]. Inappropriate shifts could result in population declines [17] and restrict range shifts (e.g. [13]).

A useful example of temporal phenotype/environment mismatches is the wall brown butterfly (Lasiommata megera), a widespread European butterfly that has probably pursued a maladaptive developmental pathway in response to changes in temperature [13]. Lasiommata megera is bivoltine in the north of its range and trivoltine in the south (figure 1b). In northwestern Europe, where distribution and abundance have been declining, L. megera has two generations per year, apart from years with warm autumns. In these years, late-season caterpillars can develop directly into a third generation or arrest development until the following year. This is an important decision as larvae die if the season ends before development is complete (figure 1b). This ‘developmental trap’ could have severe population consequences as L. megera has non-overlapping, discrete generations. Distributional gaps could arise in the transition zone between different degrees of voltinism and as the frequency of warmer autumns increases, this zone will move further poleward, potentially triggering traps in wider areas of L. megera's range.

3. Range shifts, evolutionary traps and disperser phenotype

The examples above assume that all individuals are equally susceptible to evolutionary traps during range shifts but this ignores phenotypic variability. Intra-specific variability in both the propensity for dispersal and habitat preferences could lead to the spatial segregation of phenotypes into particular areas of a species' range [18]. Within-species variability in personality (i.e. ‘behavioural syndromes’, [19]) may also be important. For example, some individuals may be consistently bold or aggressive and more likely to disperse (i.e. personality-dependent dispersal, [20]). Differences in behavioural type may facilitate range expansions, with bold, aggressive ‘colonisers’ establishing new populations, which are subsequently reinforced by shy, slow ‘joiners’ ([20], figure 2). If colonisers are more likely to encounter traps as they explore new environments, could these phenotypes be selectively removed? What are the implications of this removal for population persistence and range shifts in a changing world?

Figure 2.

Conceptual example of how dams and fish passage can cause evolutionary traps by removing particular phenotypes and impeding range shifts. (a) With no dam, individuals reproduce in their existing habitat (curved arrows). New populations occur when ‘colonisers’ (black fish) arrive in new habitat patches and subsequently reproduce, facilitating the arrival of ‘joiner’ phenotypes (orange fish). This process can facilitate further range expansion. (b) Fishways that reconnect habitats cause an evolutionary trap if ‘colonisers’ responding to a flow dispersal cue suffer elevated mortality when moving through the structure. This will lead to new populations failing to establish above dams. Existing populations may also be compromised if environmental conditions change below the dam. (c) Traps arise if fishways result in unidirectional movement to upstream areas with poorer habitat, leading to lower fitness for ‘colonisers’. In (b) and (c), the failure of ‘colonisers’ curtails the expansion of ‘joiners’, resulting in failed or impeded range shifts. Adapted from [20].

While evolutionary traps have not been commonly studied in aquatic ecosystems [6], river dams may be potential traps that selectively remove particular phenotypes. Many fishes display partial (some move) or full (all move) migration [21]. Dams disrupt migrations and can cause upstream local extinctions. Increasingly, dams are modified to reinstate fish passage (e.g. by building fishways, [22]), but these ‘improvements’ could inadvertently create traps [22,23]. For example, flow cues may attract dispersing fish into fishways where they are forced to congregate at the bottom of dams or swim upstream through small, predator-dense areas [24]. Traps could also develop if fish are attracted to fishways and move upstream into habitats with poorer conditions than below the dam [23]. These observations suggest fish passages may represent traps that selectively remove disperser phenotypes from a population.

Improving fish passage represents a form of human-mediated range expansion. We illustrate (figure 2) how traps that remove some phenotypes could affect range expansion and population persistence. If some individuals migrate to establish new populations, which are reinforced later by another phenotype (i.e. ‘colonisers’ and ‘joiners’, [20]), ‘colonisers’ that encounter traps caused by mortality in the fishway will fail to colonise new habitat and both phenotypes could experience reduced abundance if the environment below the dam becomes unsuitable (figure 2b). ‘Colonisers’ that successfully pass through the fish passage, but move into upstream habitats where their fitness is compromised (e.g. poor spawning habitat), may fail to establish. If ‘colonisers’ are required to provide information that indicates suitable habitat (e.g. via olfactory cues, [25]), this could prevent the subsequent movement of ‘joiners’, again limiting range expansion (figure 2c). While these examples are conceptual, dams that block the migration of adult Pacific salmon in Puget Sound have led to widespread loss of certain life-history types [26] and probably decreased capacity to respond to future environmental changes.

4. Conclusion

Evolutionary traps and range shifts are likely to interact as animals move in response to rapid environmental change. Animals are likely to be most strongly affected when traps result in phenotypes being poorly matched to new environments, range shifts increase encounters with traps or traps selectively remove particular phenotypes. Research is needed to test these predictions; particularly, how mismatched an animal's phenotype is to the conditions in their new habitat and how this affects their fitness and behaviour. The likelihood that animals select traps and the costs incurred when they do are probably related to life history and behaviour [7]. How intra-specific variability modifies these costs, such as whether dispersive phenotypes are more likely to get trapped, or more susceptible if they do, remain largely unexplored. Research in these areas will begin to improve our understanding of how interactions between evolutionary traps and range shifts may affect animals.

Acknowledgements

We thank Martin Genner for the invitation to contribute to this special issue, and Kate Cranney for preparing the figures. The manuscript was greatly improved by feedback from two anonymous reviewers.

Authors' contributions

All authors developed and wrote the manuscript. We all approve the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for the content.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

R.H. and S.E.S. acknowledge funding from Melbourne Water, the Centre for Aquatic Pollution Identification and Management, and the Australian Research Council (LP140100343).

References

- 1.Sih A. 2013. Understanding variation in behavioural responses to human-induced rapid environmental change: a conceptual overview. Anim. Behav. 85, 1077–1088. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.02.017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vitousek PM, Mooney HA, Lubchenco J, Melillo JM. 1997. Human domination of Earth's ecosystems. Science 277, 494–499. ( 10.1126/science.277.5325.494) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghalambor CK, McKay JK, Carroll SP, Reznick DN. 2007. Adaptive versus non-adaptive phenotypic plasticity and the potential for contemporary adaptation in new environments. Funct. Ecol. 21, 394–407. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01283.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parmesan C. 2006. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 637–669. ( 10.2307/30033846) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson BA, Rehage JS, Sih A. 2013. Ecological novelty and the emergence of evolutionary traps. Trends Ecol. Evol. 28, 552–560. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2013.04.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hale R, Swearer SE. 2016. Ecological traps: current evidence and future directions. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20152647 ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.2647) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hale R, Treml EA, Swearer SE. 2015. Evaluating the metapopulation consequences of ecological traps. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20142930 ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.2930) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Chazal J, Rounsevell MDA. 2009. Land-use and climate change within assessments of biodiversity change: a review. Glob. Environ. Change 19, 306–315. ( 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.09.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin TE. 2001. Abiotic versus biotic influences on habitat selection of coexisting species: climate change impacts? Ecology 82, 175–188. ( 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0175:avbioh]2.0.co;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pike DA. 2013. Forecasting range expansion into ecological traps: climate-mediated shifts in sea turtle nesting beaches and human development. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 3082–3092. ( 10.1111/gcb.12282) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowder L, Heppell S. 2011. The decline and rise of a sea turtle: how Kemp's ridleys are recovering in the Gulf of Mexico. Solutions 2, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowen BW, Conant TA, Hopkins-Murphy SR. 1994. Where are they now? The Kemp's ridley headstart project. Conserv. Biol. 8, 853–856. ( 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1994.08030853.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Dyck H, Bonte D, Puls R, Gotthard K, Maes D. 2015. The lost generation hypothesis: could climate change drive ectotherms into a developmental trap? Oikos 124, 54–61. ( 10.1111/oik.02066) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visser ME, Caro SP, van Oers K, Schaper SV, Helm B. 2010. Phenology, seasonal timing and circannual rhythms: towards a unified framework. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 3113–3127. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gienapp P, Reed TE, Visser ME. 2014. Why climate change will invariably alter selection pressures on phenology. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20141611 ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.1611) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sih A, Ferrari MCO, Harris DJ. 2011. Evolution and behavioural responses to human-induced rapid environmental change. Evol. Appl. 4, 367–387. ( 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2010.00166.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludwig GX, Alatalo RV, Helle P, Linden H, Lindstrom J, Siitari H. 2006. Short- and long-term population dynamical consequences of asymmetric climate change in black grouse. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 2009–2016. ( 10.1098/rspb.2006.3538) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bestion E, Clobert J, Cote J. 2015. Dispersal response to climate change: scaling down to intraspecific variation. Ecol. Lett. 18, 1226–1233. ( 10.1111/ele.12502) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sih A, Cote J, Evans M, Fogarty S, Pruitt J. 2012. Ecological implications of behavioural syndromes. Ecol. Lett. 15, 278–289. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01731.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cote J, Clobert J, Brodin T, Fogarty S, Sih A. 2010. Personality-dependent dispersal: characterization, ontogeny and consequences for spatially structured populations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 4065–4076. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0176) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman BB, Hulthén K, Brodersen J, Nilsson PA, Skov C, Hansson LA, Brönmark C. 2012. Partial migration in fishes: causes and consequences. J. Fish Biol. 81, 456–478. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03342.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLaughlin RL, Smyth ERB, Castro-Santos T, Jones ML, Koops MA, Pratt TC, Vélez-Espino L-A. 2013. Unintended consequences and trade-offs of fish passage. Fish and Fisheries 14, 580–604. ( 10.1111/faf.12003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelicice FM, Agostinho AA. 2008. Fish-passage facilities as ecological traps in large neotropical rivers. Conserv. Biol. 22, 180–188. ( 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00849.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agostinho AA, Agostinho CS, Pelicice FM, Marques EE. 2012. Fish ladders: safe fish passage or hotspot for predation? Neotrop. Ichth. 10, 687–696. ( 10.1590/S1679-62252012000400001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner CM, Twohey MB, Fine JM. 2009. Conspecific cueing in the sea lamprey: do reproductive migrations consistently follow the most intense larval odour? Anim. Behav. 78, 593–599. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.04.027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beechie T, Buhle E, Ruckelshaus M, Fullerton A, Holsinger L. 2006. Hydrologic regime and the conservation of salmon life history diversity. Biol. Conserv. 130, 560–572. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.01.019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]