Summary

Hypoxic injury is a key pathological event in a variety of diseases. Despite the clinical importance of hypoxia, modulation of hypoxic injury mechanisms for therapeutic benefit has not been achieved suggesting that critical features of hypoxic injury have not been identified or fully understood. As mitochondria are the main respiratory organelles of the cell they have been the focus of much research into hypoxic injury. Previous research has focused on mitochondria as effectors of hypoxic injury, primarily in the context of apoptosis activation [1] and calcium regulation [2]; however, little is known about how mitochondria themselves are injured by hypoxia. Maintenance of protein folding is essential for normal mitochondrial function [3], while failure to maintain protein homeostasis (proteostasis) appears to be a component of ageing [4, 5] and a variety of diseases [6, 7]. Previously it has been demonstrated that mitochondria possess their own unfolded protein response [8–10] that is activated in response to mitochondrial protein folding stress, a response that is best understood in C. elegans. As hypoxia has been shown to disrupt ATP production and translation of nuclear encoded proteins [11], both shown to disrupt mitochondrial proteostasis in other contexts [3, 12], we hypothesized that failure to maintain mitochondrial proteostasis may play a role in hypoxic injury. Utilizing C. elegans models of global [13, 14], focal [15], and cell non-autonomous hypoxic injury we have found evidence of mitochondrial protein misfolding post-hypoxia, and that manipulation of the mitochondrial protein folding environment is an effective hypoxia protective strategy.

Results

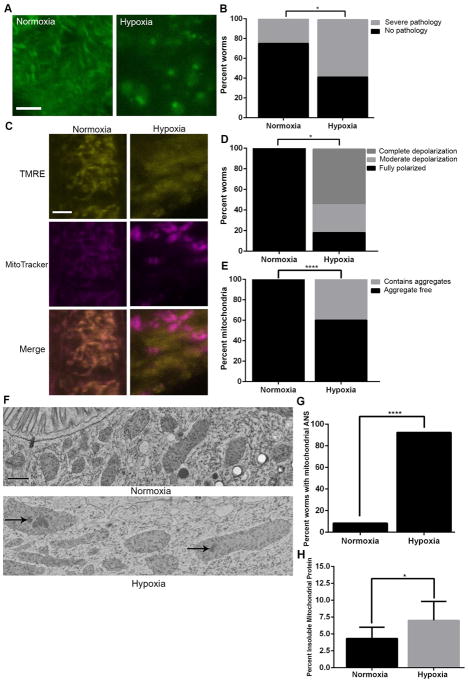

We first asked whether hypoxia induces pathological changes in C. elegans mitochondria. We performed confocal microscopy on worms exposed to sublethal hypoxia (Figure 1A–B). Although these short hypoxic exposures resulted in no organismal death, they led to abnormal mitochondrial morphology. Next we assessed mitochondrial membrane potential by examining the degree of colocalization of a voltage insensitive dye (MitoTracker Deep Red) and a voltage sensitive dye (TMRE) [16]. Following hypoxia, we observed widespread MitoTracker positive and TMRE negative mitochondria, indicative of depolarization (Figure 1C–D). Next, we performed electron microscopy (EM) of worms exposed to hypoxia. Strikingly, we observed aggregates within the mitochondria of a variety of worm cell types following hypoxia (Figure 1E–F). The aggregates resembled those observed following mitochondrial protease knockdown [17]. Suspecting that these aggregates consisted of proteins, we made use of the dye 1,8-ANS, which fluoresces when bound to hydrophobic surfaces, such as misfolded proteins [18]. Following a mild hypoxic exposure that produces no permanent organismal damage [13], we observed marked ANS fluorescence in mitochondria (Figures 1G and S1). In order to quantify the extent of protein misfolding, we isolated mitochondria following a hypoxic exposure and determined the percentage of insoluble proteins [8, 19]. We observed a significant increase in insoluble mitochondrial proteins immediately following a hypoxic exposure, indicative of severe mitochondrial protein misfolding (Figure 1H).

Figure 1. Mitochondrial proteostasis is disrupted by hypoxia.

(A to B) Intestinal mitochondria with mitochondrially targeted GFP (zcIs17) exhibit severe pathology following sublethal (12 hours) hypoxia, scale bar, 4μm, * P < 0.05 (Fisher’s exact test). (C to D) Intestinal mitochondria display reduced TMRE and MitoTracker Deep Red colocalization following sublethal (12 hours) hypoxia, indicating mitochondrial depolarization, scale bar, 4μm,* P < 0.05 (Chi squared test). (E to F) Sublethal (12 hours) hypoxia leads to the appearance of intramitochondrial aggregates (arrows), scale bar, 400nm, **** P < 0.001 (Fisher’s exact test). (G) Percent of images displaying mitochondrial localization of 1,8-ANS following mild (4 hours) hypoxia, **** P < 0.001 (Fisher’s exact test). (H) Percent of total mitochondrial protein insoluble in Triton X-100, bars are mean ± standard error (SEM), ** P < 0.01 (paired T-test).

Mitochondria possess their own unfolded protein response, the mtUPR [10], that leads to upregulation of mitochondrial chaperones. The hypothesis that hypoxia induces mitochondrial protein misfolding predicts that the mtUPR should be induced by hypoxia. To test this, we made use of reporters of transcriptional induction of hsp-6 and hsp-60, which encode mitochondrial chaperones linked to the mtUPR [9]. Following hypoxia we observed two-fold induction of both the zcIs13[Phsp-6::GFP] and zcIs9[Phsp-60::GFP] reporters (Figures 2A, S2A). Surprisingly, this was seen following a brief, four hour hypoxic exposure, which previously has been shown to be followed by complete behavioral recovery in C. elegans [13]. These findings indicate that mitochondrial proteostasis is exquisitely sensitive to hypoxic stress and its disruption occurs early in hypoxic injury.

Figure 2. Activation of the mtUPR is hypoxia protective.

(A) Induction of the mtUPR reporter, zcIs13[Phsp-6::GFP] following mild (4 hours) hypoxia, each point represents total fluorescence of one worm, bars are mean ± standard deviation (SD). (B) Survival of wild-type (N2) and mtUPR deletion mutants on control (L4440), and cco-1 RNAi following 20 hours of hypoxia, bars are mean ± SEM. (C) Survival of N2 and mtUPR mutants or RNAi, treated with control or 5μg/ml doxycyline 24 hours prior to 18 hours of hypoxia, bars are mean ± SEM. (D) Survival of N2 worms on control, or indicated RNAi after 18 hours of hypoxia, bars are mean ± SEM. (E) Oxygen consumption rate (μmol/mg protein*min) of N2 worms raised on control or indicated RNAi, bars are mean ± SEM. (F) Survival of N2 and atfs-1(gf) alleles following 20 hours of hypoxia, bars are mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, **** P < 0.001, ns, no significant difference by Student’s T-Test (A), paired T-Test (B to C), One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (D to F). A.U., arbitrary units.

Based on our above findings, we predicted that the mtUPR would promote organismal survival following hypoxia. Stoichiometric disruption of electron transport chain (ETC) complex subunits has been shown to induce the mtUPR [20], and can be accomplished in C. elegans by RNAi knockdown of cco-1, a component of complex IV. Following knockdown of cco-1, we observed an increase in hypoxic survival of wild-type (N2) worms (Figures 2B, S2B). In order to confirm that the observed resistance was due to induction of the mtUPR, rather than another effect of cco-1 knockdown, we assayed for suppression of cco-1 hypoxia resistance in strains containing knockouts of mtUPR activating genes, and observed that the protection was dependent on the mtUPR gene atfs-1 (Figures 2B, S2B). ATFS-1 is a transcription factor that is normally targeted to the mitochondria and degraded, but under conditions of mitochondrial protein folding stress, it translocates to the nucleus and activates the mtUPR [21–23].

We next tested whether doxycycline (a pharmacological mtUPR inducer [20]) was also hypoxia protective. Again we observed hypoxia protection of wild-type worms (Figure 2C), in an atfs-1 dependent manner. We also observed that this protection is dependent on haf-1, a mitochondrial ABC transporter, required for mtUPR activation following mild mitochondrial proteostasis stressors such as doxycycline [10, 21]. However, the haf-1 mutant did not suppress the cco-1 hypoxia-resistant phenotype (Figure 2B). In addition to haf-1, the mtUPR transcriptional co-activator gene dve-1 [10] was necessary for doxycycline mediated hypoxia protection (Figure 2C). Based on the above data it is expected that doxycycline is producing hypoxia protection by stimulating additional mtUPR induction. Consistent with this, we found that induction of the mtUPR with doxycycline is additive with the induction seen following hypoxia (Figure S2C).

Surprisingly, the atfs-1(tm4919) strain appeared to exhibit mild hypoxia resistance under the conditions used for testing doxycycline. We confirmed this mild hypoxia resistance by testing both atfs-1(tm4919) and atfs-1(tm4525) under more modest hypoxic conditions (Figure S2B) and found these strains to have mild, reproducable hypoxia resistance. One possible explanation for the observed resistance is that in the absence of ATFS-1, alternative pathways are activated to maintain mitochondrial proteostasis. Indeed, the more severe embryonic lethal phenotype of the hsp-6 null allele indicates that HSP-6 functions in the absence of ATFS-1 [24]. We also asked whether atfs-1(lf) was generally suppresive to hypoxia resistance. We tested rars-1 RNAi [13] in both wild-type and atfs-1(lf) worms and found both to be similarly protected from hypoxia, indicating that ATFS-1 is required for hypoxia resistance for mtUPR activators, but not for this other method of inducing hypoxia resistance (Figure S2D).

In order to confirm that the hypoxia protection observed with doxycycline and cco-1 RNAi was generalizable to other methods of mtUPR induction, we tested RNAi knockdown of three additional proteins shown to induce the mtUPR [25], two of which are not believed to play any role in the ETC. Like cco-1 RNAi, knockdown of nduf-6 (an ETC gene), lpd-9 (a lipid metabolism gene) and letm-1 (shown to regulate mitochondrial volume [26]) were all hypoxia protective (Figure 2D). An alternative explanation of the protective effects seen with the above treatments is that they lead to a reduction in oxygen consumption. However, knockdown of lpd-9 and letm-1 had no effect on oxygen consumption (Figure 2E). While cco-1 RNAi did reduce oxygen consumption as expected, this reduction in oxygen consumption was not suppressed by atfs-1(lf) unlike cco-1 RNAi’s hypoxia resistance (Figure S2E). Finally, we tested three strains with mutations in the mitochondrial targeting signal of atfs-1, leading to constitutive targeting of ATFS-1 to the nucleus and activation of the mtUPR [27]. These gain of function mutations in the atfs-1 gene (leading to constitutive mtUPR activation) were sufficient to protect against a severe hypoxic injury, which led to the death of wild-type worms (Figure 2F), indicating that mtUPR activation by ATFS-1 is sufficient to protect against hypoxic injury.

These data demonstrate that pre-hypoxic mtUPR activation can prevent organismal death. A more therapeutically relevant action would be for the mtUPR to block hypoxic damage after the hypoxic event has occurred. In order to address this, we induced activation of the mtUPR via doxycycline following hypoxia, and observed approximately a doubling of survival in worms (Figure 3A). Consistent with a mtUPR dependent mechanism we observed suppression of this protection by an atfs-1(lf) mutation. These data indicate that the mtUPR can not only prevent hypoxic damage, but can rescue animals from lethal injury after the precipitating event has already occurred. As loss of function of the insulin IGF receptor, daf-2, leads to hypoxia resistance [14], we therefore wanted to see if daf-2(lf) was additive with mtUPR mediated protection. Using a hypoxia resistant allele, daf-2(e1368), we found that mtUPR mediated hypoxia protection was additive with daf-2(lf) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. mtUPR protects before and after global and focal hypoxic injury.

(A) Survival of worms with control or doxycyline (10μg/ml) solutions applied only after 18 hours of hypoxia, bars are mean ± SEM. (B to C) Survival or locomotion deficits (Unc) of focally injured worms with control or doxycyline (10μg/ml) solutions 24 hours before (B) or immediately after (C) hypoxia. rars-1(gc47) = Control, rars-1(gc47);gcSi2[Pmyo-2::YFP::unc-54 3′-UTR] = Transformation Control, rars-1(gc47);gcIs3[Pmyo-2::rars-1(+)::unc-54 3′-UTR] = Pharyngeal Myocytes, rars-1(gc47);gcSi4[Punc-47::rars-1(+)::unc-54 3′-UTR] = GABA Neurons (D to E) Treatment with doxycyline both before (D), and after (E) hypoxia prevents hypoxic mitochondrial pathology. (F) cco-1 RNAi partially prevents appearance of intramitochondrial aggregates following sublethal (12 hour) hypoxia (L4440 data reproduced from Figure 1E). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, **** P < 0.001, ns, no significant difference by Student’s T-test (A), or Chi squared test (B to F)

As the previous experiments have all occurred under conditions of global hypoxia, we next tested to see if activation of the mtUPR is protective in a focal model of hypoxic injury [15]. The strains used for this model include two control strains where the whole worm is hypoxia resistant: rars-1(gc47) (control) and rars-1(gc47);gcSi2 (transformation control) along with two strains with selective tissue vulnerability to hypoxic injury: rars-1(gc47);gcIs3 (vulnerable pharyngeal myocytes) and rars-1(gc47);gcSi4 (vulnerable GABA neurons). As in the global model of hypoxic injury, induction of the mtUPR increased organismal health and survival when induced both before (Figure 3B) and after (Figure 3C) focal hypoxic injury.

Thus far, we have not shown that the mitochondria themselves are protected by the mtUPR. To address this, we scored mitochondrial morphology after hypoxia and found that mtUPR induction both before (Figure 3D) and after (Figure 3E) hypoxia blocked the observed hypoxic mitochondrial pathology. Importantly, we also observed by EM, that cco-1 RNAi led to a reduction in the percentage of mitochondria containing aggregates, while not altering mitochondrial size or the fractional area occupied by aggregates in those mitochondria with aggregates (Figures 3F and S3).

A surprising feature of some proteostatic mechanisms is the ability of activation of proteostatic mechanisms in one tissue to protect other tissues. Previously, the C. elegans mtUPR has been found to prolong lifespan and can be activated in a cell non-autonomous manner [28]. However, cell specific markers of ageing are lacking, leading to difficulty in separating cell autonomous mtUPR effects from non-autonomous ones. We examined the ability of non-autonomous activation of the mtUPR to protect against hypoxic injury. For these experiments we made use of three strains: sid-1(qt9) (blocks dsRNA uptake and spreading), sid-1(qt9);uthIs375[Punc-119::cco-1HP] (mtUPR induction in neurons by cco-1 inverted repeat hairpin), and sid-1(qt9);uthIs326[Pges-1::cco-1HP] (mtUPR induction in intestines) [28]. The strains with focal mtUPR induction exhibited organismal hypoxia resistance relative to sid-1(qt9) controls (Figure 4A). In order to detect cell non-autonomous protection of tissues, we exposed worms to a sublethal hypoxic exposure, resulting in abolition of pharyngeal pumping in the vast majority of control worms, a behavior that requires pharyngeal myocytes but not intestinal or neuronal cells [29]. Consistent with cell non-autonomous mtUPR protection, we observed preservation of pharyngeal pumping in both cco-1 hairpin containing strains (Figure 4B). Finally, we examined mitochondria in the intestines of worms with neuronal mtUPR induction, and observed protection of mitochondrial morphology from hypoxic pathology (Figure 4C). In concert, these findings demonstrate that the mitochondrial protein folding environment is disrupted by hypoxia, and that induction of the mtUPR can protect against global, focal, and cell non-autonomous hypoxic injury.

Figure 4. Cell non-autonomous mtUPR induction is hypoxia protective.

(A) Organismal survival of sid-1(qt9) (control) relative to AGD1079 (neuronal mtUPR induction) and AGD324 (intestinal induction) following 18 hours of hypoxia, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 (Student’s T-test). (B) Following sublethal (12 hour) hypoxia pharyngeal pumping rate in sid-1(qt9) controls compared to strains with neuronal (AGD1079) and intestinal (AGD324) mtUPR induction, bars are mean ± SD **** P < 0.001 (Student’s T-test). (C) Following sublethal (12 hour) hypoxia, percent of worm with severely abnormal intestinal mitochondrial morphology in control (sid-1(qt9);zcIs17) or neuronal mtUPR induction (sid-1(qt9);zcIs17;uthIs375) strains, **** P < 0.001 (Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

We have shown that failure of mitochondrial protein homeostasis is an early feature of hypoxia. We found that upregulation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response is protective at the mitochondrial and organismal levels in models of global, focal, and cell non-autonomous hypoxic injury. Even with hypoxic exposures that cause no permanent behavioral deficits [13], mitochondrial protein misfolding is increased, which implies that some level of mitochondrial proteostatic failure is an early feature of hypoxic injury and that it is not immediately lethal and can be tolerated at the organismal level. Two possible explanations for this are that either a certain amount of protein misfolding can be tolerated and repaired before proteostatic mechanisms are overwhelmed, or that proteins exhibit differential sensitivity to hypoxic induced protein misfolding and that essential mitochondrial proteins are resistant and only misfold with lethal hypoxic exposure. This later explanation is consistent with previous studies [4] that have found differential propensities for age induced protein aggregation, influenced in part, by the presence or absence of certain structural motifs.

Interestingly, the protective effects of mtUPR activation can occur with either pre or post-hypoxic induction of the mtUPR. Given that mitochondrial protein misfolding is evident immediately after a mild hypoxic exposure, this implies that there may be a window period in between the hypoxic exposure and death during which activation of mitochondrial proteostatic mechanisms can reverse or prevent further irreversible lethal injury. Future characterization of this window period may be important for the development of therapeutics to treat hypoxic injury.

Experimental Procedures

Strains

Worms were maintained as previously described [15]. N2 (var. Bristol) [30] was used as the wild-type strain. Strains containing integrated arrays zcIs17[Pges-1::GFPmt], zcIs13 V[Phsp-6::GFP], zcIs9 V[Phsp-60::GFP], or alleles daf-2(e1368), atfs-1(et15), atfs-1(et17), and atfs-1(et18) were acquired from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC). Strains containing atfs-1(tm4919), atfs-1(tm4525), and haf-1(tm843) were provided by the Mitani Lab through the National Bio-Resource Project of the MEXT, Japan. Strains AGD1079 (sid-1(qt9);uthIs375[Punc-119::cco-1HP]) and AGD324 (sid-1(qt9);uthIs326[Pges-1::cco-1HP]) were provided by A. Dillin. The control strain, sid-1(qt9) was generated by outcrossing AGD1079 with N2.

Light Microscopy

Confocal microscopy was performed using a Leica TCS SPE or TCS SP8. Dyes MitoTracker Deep Red, 1,8-ANS(1-Anilinonaphthalene-8-Sulfonic Acid) (Life Technologies), TMRE (Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester perchlorate, Sigma), were added to plates containing worms 24 hours prior to imaging. Scoring of images was conducted by an observer blinded to condition. Images were scored as containing severe pathology if there was an absence of healthy, slim, tubular mitochondria. Mitochondrial polarization was scored by examining the percentage of mitochondria within an image that displayed colocalization of MitoTracker Deep Red and TMRE. Images were scored as fully polarized if all MitoTracker positive mitochondria colocalized with TMRE, completely depolarized if there was no colocalization, and moderately depolarized if there was partial colocalization. Assessment of hsp-6 and hsp-60 induction was performed by imaging worms containing the integrated array zcIs13 or zcIs9 on a Zeiss Axioskop2 microscope. Fluorescence intensity was quantified by NIH ImageJ.

Electron Microscopy

Samples were prepared for EM 1 day after a 12 hour hypoxic or normoxic exposure. Worms underwent high pressure freezing and were stored in liquid nitrogen. Samples underwent automatic freeze substitution using a Leica EM AFS2 or manual fixation by gradually being warmed to room temperature over 16 hours in frozen 4% osmium tetroxide in acetone. Samples were stained with uranyl acetate, embedded in a plastic resin and sectioned. Samples were post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Percent of mitochondria containing aggregates was assessed by a reviewer blinded to condition. Mitochondrial length was assessed using NIH ImageJ. Fractional area occupied by aggregates was assessed by dividing aggregate length by length of major and minor axes of mitochondria.

Hypoxic Exposure

Hypoxic and normoxic exposures and scoring were performed as previously described [31]. For strains containing rars-1(gc47), worms were scored as dead if there was no spontaneous movement or response to stimulation with platinum wire and were scored as uncoordinated (unc) if prodding only elicited movement of the head or tail.

Mitochondrial Isolation and Protein Analysis

Mitochondria were isolated from C. elegans immediately following 4 hours of hypoxia using Mitochondria Isolation Kit for Tissues (MitoSciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Mitochondria were resuspended in a detergent solution (0.5% Triton-X100, 1mM DTT, 1mM EDTA, 10mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitor (Roche)). Isolation of Triton insoluble proteins was performed as previously described [19]. Protein concentration was determined in triplicate by spectrophotometry at 280 nm (ND-1000, Nanodrop Technologies), and normalized to total protein for each sample.

RNAi

Feeding RNAi was performed as previously reported [32], however, LB was used instead of 2xYT and tetracycline was not used.

Oxygen Consumption

Oxygen consumption assays were performed on adult (L4 + 1 day) worms as previously described [32].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Dillin for providing strains AGD1079 and AGD324. We thank Marc Van Gilst for his comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by R01-NS045905 and R21-NS084360-02 from the NINDS and T32-GM07200 from the NIGMS.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: D.M.K. performed experiments. D.M.K. and C.M.C designed the experiments and wrote the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Crow MT, Mani K, Nam YJ, Kitsis RN. The mitochondrial death pathway and cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circulation research. 2004;95:957–970. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148632.35500.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristian T. Metabolic stages, mitochondria and calcium in hypoxic/ischemic brain damage. Cell calcium. 2004;36:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker MJ, Tatsuta T, Langer T. Quality control of mitochondrial proteostasis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David DC, Ollikainen N, Trinidad JC, Cary MP, Burlingame AL, Kenyon C. Widespread protein aggregation as an inherent part of aging in C. elegans. PLoS biology. 2010;8:e1000450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu AL, Murphy CT, Kenyon C. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science. 2003;300:1142–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.1083701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calamini B, Morimoto RI. Protein homeostasis as a therapeutic target for diseases of protein conformation. Current topics in medicinal chemistry. 2012;12:2623–2640. doi: 10.2174/1568026611212220014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosser DD, Caron AW, Bourget L, Meriin AB, Sherman MY, Morimoto RI, Massie B. The chaperone function of hsp70 is required for protection against stress-induced apoptosis. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:7146–7159. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7146-7159.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Q, Wang J, Levichkin I, Stasinopoulos S, Ryan M, Hoogenraad N. A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells. The EMBO journal. 2002;21:4411–4419. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoneda T, Benedetti C, Urano F, Clark SG, Harding HP, Ron D. Compartment-specific perturbation of protein handling activates genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. Journal of cell science. 2004;117:4055–4066. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pellegrino MW, Nargund AM, Haynes CM. Signaling the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1833:410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Willis AE. Translational regulation of gene expression during conditions of cell stress. Molecular cell. 2010;40:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jovaisaite V, Mouchiroud L, Auwerx J. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response, a conserved stress response pathway with implications in health and disease. The Journal of experimental biology. 2014;217:137–143. doi: 10.1242/jeb.090738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson LL, Mao X, Scott BA, Crowder CM. Survival from hypoxia in C. elegans by inactivation of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Science. 2009;323:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1166175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott BA, Avidan MS, Crowder CM. Regulation of hypoxic death in C. elegans by the insulin/IGF receptor homolog DAF-2. Science. 2002;296:2388–2391. doi: 10.1126/science.1072302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun CL, Kim E, Crowder CM. Delayed innocent bystander cell death following hypoxia in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell death and differentiation. 2013 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cottet-Rousselle C, Ronot X, Leverve X, Mayol JF. Cytometric assessment of mitochondria using fluorescent probes. Cytometry Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2011;79:405–425. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein SH, Venkatesh S, Li M, Lee J, Lu B, Hilchey SP, Morse KM, Metcalfe HM, Skalska J, Andreeff M, et al. The mitochondrial ATP-dependent Lon protease: a novel target in lymphoma death mediated by the synthetic triterpenoid CDDO and its derivatives. Blood. 2012;119:3321–3329. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-340075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadley KC, Borrelli MJ, Lepock JR, McLaurin J, Croul SE, Guha A, Chakrabartty A. Multiphoton ANS fluorescence microscopy as an in vivo sensor for protein misfolding stress. Cell stress & chaperones. 2011;16:549–561. doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pimenta de Castro I, Costa AC, Lam D, Tufi R, Fedele V, Moisoi N, Dinsdale D, Deas E, Loh SH, Martins LM. Genetic analysis of mitochondrial protein misfolding in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell death and differentiation. 2012;19:1308–1316. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houtkooper RH, Mouchiroud L, Ryu D, Moullan N, Katsyuba E, Knott G, Williams RW, Auwerx J. Mitonuclear protein imbalance as a conserved longevity mechanism. Nature. 2013;497:451–457. doi: 10.1038/nature12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nargund AM, Pellegrino MW, Fiorese CJ, Baker BM, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial import efficiency of ATFS-1 regulates mitochondrial UPR activation. Science. 2012;337:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1223560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes CM, Yang Y, Blais SP, Neubert TA, Ron D. The matrix peptide exporter HAF-1 signals a mitochondrial UPR by activating the transcription factor ZC376.7 in C. elegans. Molecular cell. 2010;37:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker BM, Nargund AM, Sun T, Haynes CM. Protective coupling of mitochondrial function and protein synthesis via the eIF2alpha kinase GCN-2. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura K, Tanaka N, Nakamura N, Takano S, Ohkuma S. Knockdown of mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 promotes progeria-like phenotypes in caenorhabditis elegans. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:5910–5918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett CF, Vander Wende H, Simko M, Klum S, Barfield S, Choi H, Pineda VV, Kaeberlein M. Activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response does not predict longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature communications. 2014;5:3483. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasegawa A, van der Bliek AM. Inverse correlation between expression of the Wolfs Hirschhorn candidate gene Letm1 and mitochondrial volume in C. elegans and in mammalian cells. Human molecular genetics. 2007;16:2061–2071. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rauthan M, Ranji P, Aguilera Pradenas N, Pitot C, Pilon M. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response activator ATFS-1 protects cells from inhibition of the mevalonate pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:5981–5986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218778110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durieux J, Wolff S, Dillin A. The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell. 2011;144:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avery L, You YJ. WormBook : the online review of C. elegans biology. 2012. C. elegans feeding; pp. 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao XR, Crowder CM. Protein misfolding induces hypoxic preconditioning via a subset of the unfolded protein response machinery. Molecular and cellular biology. 2010;30:5033–5042. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00922-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott B, Sun CL, Mao X, Yu C, Vohra BP, Milbrandt J, Crowder CM. Role of oxygen consumption in hypoxia protection by translation factor depletion. The Journal of experimental biology. 2013;216:2283–2292. doi: 10.1242/jeb.082263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.