Preterm births (< 37 weeks’ gestation) are increasing worldwide and account for 8% of Canadian births.1 With advances in perinatal care over the last 20–30 years, more than 90% of preterm infants survive and enter adulthood.2 The “Barker hypothesis” of fetal origins of adult disease was supported by studies that found associations between low birth weight and adult diseases, such as cardiovascular disease.3 Although those pioneering studies did not distinguish low birth weight due to intrauterine growth restriction in full-term newborns from prematurity, mounting evidence now suggests that preterm birth, above and beyond low birth weight, may lead to hypertension, cardiac dysfunction, obstructive lung disease, glucose intolerance and osteopenia.

There are no guidelines for the long-term medical follow-up of people born preterm. Recently, it was proposed that physicians should enquire about neonatal history throughout the life span, particularly because the risk of premature death is increased by 40% in young adults who were born preterm.4,5 Identifying preterm birth as a risk factor for early-onset chronic disease is critical in implementing preventive strategies and targeted screening to halt disease progression and to avoid premature death.

We review evidence linking preterm birth to adult chronic ailments, focusing mainly on evidence from systematic reviews and observational cohort studies, to provide a guide for physicians providing treatment to adults who were born preterm (Box 1).

Box 1: Evidence used in this review.

We searched PubMed for articles published in English between March 2005 and February 2015 using the medical subject headings “infant, premature” and “infant, low birth weight” in combination with the following key words: “cardiovascular,” “hypertension,” “insulin sensitivity,” “metabolic syndrome,” “pulmonary outcomes,” “osteopenia,” “bone mass,” “adult outcome.” In addition, we reviewed relevant papers identified from the reference lists of retrieved articles. We included systematic reviews and observational cohort studies that compared people born preterm with those born at term as the control groups.

Why are young adults born preterm at greater risk of chronic diseases?

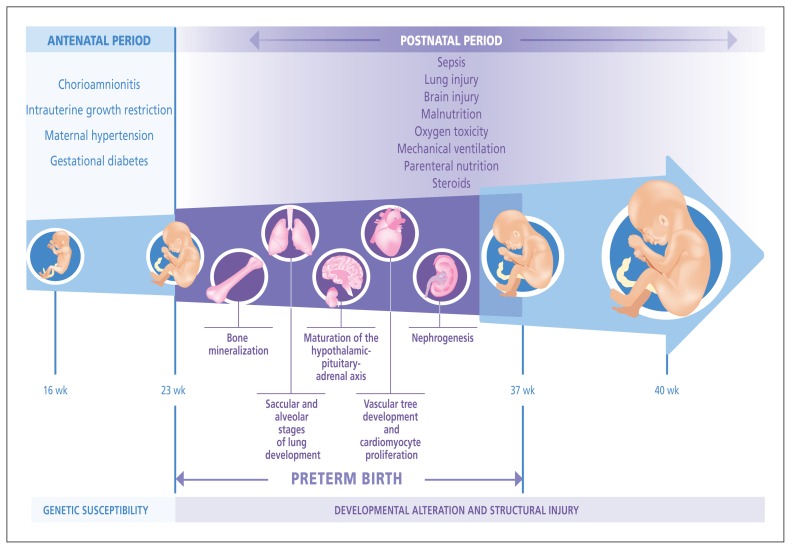

Preterm infants are exposed to various sources of injury both in utero and after birth at a time when their organ systems are at a critical stage of development (Figure 1). The fetus or newborn will undergo adaptive mechanisms that may be deleterious in the long-term owing to permanent alterations in organ system development, possibly through epigenetic and genetic mechanisms.6 Moreover, perinatal events could directly cause structural injury through inflammatory processes and abnormal repair.7 In preterm infants, these disturbances induce a phenotype that might heighten their risk for later chronic diseases because of morphologic and functional changes in the infants’ organ systems.

Figure 1:

Common adverse intrauterine conditions that may trigger preterm birth (e.g., preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, fetal growth restriction and chorioamnionitis) can influence fetal programming. After birth, complications related to prematurity such as sepsis, lung and brain injury, and malnutrition — and their treatments (e.g., oxygen, parenteral nutrition, steroids) — further alter organ system development.

Specific perinatal factors confer additional risk for organ dysfunction, and their presence should be assessed by clinicians: being born to a mother with gestational hypertension or diabetes, intrauterine growth restriction, birth weight of less than 1500 g and prolonged oxygen dependence after birth.5,6

What is the effect of preterm birth on cardiovascular health?

Preterm birth is associated with greater risk of hypertension and changes in cardiovascular structure and function that are typically seen in people at risk of heart failure. A Swedish cohort study involving 674 820 participants documented a 7% higher risk of dying in young adulthood from cardiovascular disease for each week of increased prematurity (hazard ratio 0.93, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.88–0.99).4 In addition, young adults born very prematurely (< 32 weeks’ gestation) from another prospective cohort (n = 1 306 943) showed a 1.89-fold increased hazard of cerebrovascular diseases compared with peers born at term (95% CI 1.01–3.54).8

Hypertension has consistently been shown to be more prevalent among adults born preterm, with an inverse correlation between systolic blood pressure and gestational age.9 Meta-analyses have shown higher resting systolic blood pressure (mean difference [MD] 3.8 mm Hg, 95% CI 2.6 to 5.0 mm Hg) in people born preterm from childhood to young adulthood, along with higher diastolic blood pressure (MD 2.6 mm Hg, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.0 mm Hg) and 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure (MD 3.1 mm Hg, 95% CI 0.3 to 6.0 mm Hg).10–12 The effect of prematurity on blood pressure is of particular relevance for women during their reproductive years. In a Canadian population-based study, women who had been born very premature had a 50% increased risk of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and chronic hypertension compared with women who had been born at term.9

Structural and functional changes that mediate programing of hypertension and cardiovascular disorders following preterm birth are still unclear but likely involve multiple organ systems including the vasculature and heart, kidneys and sympathetic nervous system.13,14 Recent comprehensive vascular phenotyping in people born preterm showed structural macrovascular changes — particularly a narrowing of the aorta — and microvascular dysfunction evident by early adulthood.15 These long-term changes may, in part, be driven by coassociated perinatal factors such as maternal hypertension and postnatal interventions rather than preterm birth.16,17

In addition, preterm birth appears to have a direct effect on myocardial tissue. In a prospective cohort study, 102 young adults (20–39 yr) born preterm (mean 30 ± 2 weeks’ gestation) and 132 members of a control group born at term underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Participants born preterm had altered cardiac shape characterized by increased left and right ventricular mass and reduced ventricular volumes.18,19 Prolonged neonatal ventilation was a risk factor for greater right ventricular mass. Impaired systolic and diastolic function, which was more pronounced on the right than on the left side, was also documented: 6 of 102 members of the preterm group versus none of the members of the control group displayed mild right ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction of 42%–45%).

National pediatric organizations currently recommend annual blood pressure measurement starting at three years of age to detect early secondary hypertension.20,21 Given the clear association between preterm birth and hypertension, blood pressure should be measured regularly from childhood to allow for early management of cardiovascular disease risk. Pregnant women who were born preterm should undergo careful blood pressure monitoring. Cardiac and vascular phenotype may offer a means to stratify a patient’s risk.

Does preterm birth increase the risk of metabolic syndrome?

Adverse metabolic changes contributing to risk of diabetes and cardiovascular events are seen following preterm birth, but results are inconsistent. A Swedish cohort study involving 630 090 young adults born in the 1970s with long-term follow-up at 25–37 years of age showed that people born preterm had a 13% increased use of insulin or orally administered hypoglycemia agents compared with members of a control group born at term (odds ratio [OR] 1.13, 95% CI 1.02–1.26).22 Furthermore, odds of gestational diabetes were much higher in pregnant women who had been born very prematurely than in those who had been born at term (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.65–3.33) in a cohort study.9 Conversely, a meta-analysis examining components of the metabolic syndrome found higher blood pressure and higher fasting low-density lipoprotein levels in adults born preterm than in peers born at term, but no difference in body mass index, fat distribution, fasting glucose, fasting insulin or levels of high-density lipoprotein and triglycerides.11 Yet, a recent population-based cohort study (n = 711) showed that odds of fulfilling the criteria for metabolic syndrome were 3.7 higher (95% CI 1.6–8.2) in young adults who had been born at less than 34 weeks than in their peers born at term.23

The link between preterm birth and insulin sensitivity was the subject of a recent systematic review.24 In early childhood, reduced insulin sensitivity was seen following preterm birth, but as children aged, the strength of this association decreased. In three of the studies reviewed, fat mass was the strongest determinant of insulin sensitivity in young adults born preterm, but contradictory results were seen in two other studies in which the effect of preterm birth persisted irrespective of anthropometric measures.24 Patients enrolled in published studies were less than 30 years old, and thus longer term follow-up will more clearly determine whether aging interacts with prematurity to increase risk of metabolic syndrome. Indeed, comprehensive assessment of glucose homeostasis in more than 100 young adults (aged 18–27 yr) with a birth weight of less than 1500 g (gestational age 24–36 wk) and more than 100 members of a control group born at term showed that reduced insulin sensitivity was compensated for by increased insulin secretory response. This compensation could, over time, lead to pancreatic β-cell exhaustion and the development of diabetes.25,26

The mechanisms leading to abnormal metabolic homeostasis in people born preterm are complex and remain unclear, but they could involve nutritional deficits both in utero (particularly in growth-restricted newborns) and after delivery, where parenteral nutrition given in the neonatal unit may be insufficient to compensate for energy demand. Rapid crossing of growth percentiles for weight without a parallel catch-up for length may then foster an obesogenic phenotype.27,28

Data linking preterm birth to the metabolic syndrome are insufficient to recommend screening for type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia beyond what is currently suggested by the Canadian and American diabetes associations. Primary care physicians may consider preterm birth along with predisposing conditions, such as obesity, when determining a patient’s overall risk of metabolic syndrome.

Are we seeing a new pulmonary overlapping syndrome?

Young adults born preterm, particularly those with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD, the chronic lung disease of prematurity), have impaired respiratory function characterized by persistent and frequent respiratory symptoms, such as chronic cough, dyspnea and wheezing, in addition to signs of airway obstruction.29 About 10% of adults who were born preterm use bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids, compared with 4%–6% of those born at term.30,31

Systematic reviews have reported abnormal pulmonary function testing, consistent with airflow limitation in the proximal and more distal airways, among adults born preterm, as evidenced by reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced mid-expiratory flow.29,32 Forced expiratory volume was 0.77 standard deviations (SDs) (95% CI −0.94 to −0.60) lower in young adults who were born preterm than in those born at term, which is equivalent to a 10% decrease in predicted value.32 Patients with BPD had even greater reductions in FEV1 compared with those without the disease (MD −0.83 SD, 95% CI −1.01 to −0.64).32 Unlike in patients with asthma, airflow obstruction was only partially reversible after administration of bronchodilators, with 68%–72% of children with BPD not responding at all to such treatment.33,34 These results suggest that structural changes originating in the neonatal period may lead to fixed reductions in airway caliber. At the alveolar level, impaired gas transfer has been documented with lower diffusion capacity in patients born preterm.29 Radiological studies using chest computed tomography have almost universally described abnormal findings, including fibrosis, air trapping and even emphysema, in patients with BPD and in most preterm infants without BPD born at or before 28 weeks’ gestation.29,35

Peak lung growth and function are reached in the 20s before natural age-related decline takes place. Patients with BPD or people born preterm who smoke have a greater decline in the ratio of FEV1 to FVC between the ages of 8 and 18 years.36 Concerns exist as to whether preterm birth may predispose the patient to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In addition, given the adverse effect of prematurity on vascular development, pulmonary vascular disease such as pulmonary hypertension could emerge as an additional morbidity in adulthood, but this has not yet been investigated.37

Patients who were born preterm and who have persistent respiratory symptoms should undergo pulmonary function testing to document airway obstruction and bronchodilator response to guide management. However, evidence is currently lacking regarding the best therapeutic strategy.

Is normal peak bone mass achieved in adults born preterm?

Failure to achieve peak bone mass following prematurity with subsequent increased risk of osteoporosis is a concern, given that 80% of bone mineral accretion occurs during the last gestational trimester. Furthermore, preterm infants experience nutritional deficits during the neonatal period in addition to prolonged immobilization and exposure to calcium-wasting medication. Yet, studies on long-term bone health in patients born preterm are scarce, and their results are equivocal. In a Finnish observational cohort study, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry was performed to examine bone mineral density. Low bone density (z score ≤ −1 unit) was detected in 44% of the 144 young adults born preterm and in 26% of the 139 members of the at-term control group, representing a 2.3-fold increased odds (95% CI 1.4–3.8).38 In contrast, gestational age was not related to bone density in two other well-designed prospective cohort studies.39,40 However, participants in those studies were born less prematurely (30–35 wk) and were relatively healthy in the neonatal period, which suggests a possible threshold in gestational age below which prematurity-related medical complications may interfere permanently with bone development.

Given the potential increased risk of low bone density and possible subsequent fractures, adults who were born preterm should be reminded to eat a calcium-rich diet and engage in weight bearing activities.

Conclusion

A substantial proportion of current youth and adults were born preterm. This population is at increased risk of developing chronic health problems. Most problems are pulmonary. Cardiovascular and metabolic problems may also occur and, in women, may become most evident during pregnancy. Early detection of risk factors and subclinical disease states in patients who were born prematurely is critical to mitigating undesirable health events. It is our role as clinicians to identify patients at risk by enquiring about perinatal history to the same extent that we ask about smoking or family history of early cardiovascular death.

Future studies should examine the mechanisms that induce changes in organ structure and function following preterm birth, to identify targets for early interventions, improvements in perinatal practices and pharmacologic or behavioral modalities that could improve overall health outcomes (Box 2).

Box 2: Unanswered questions.

Are signs and symptoms of chronic adult ailments the result of a static injury during the neonatal period (arrested development) or a progressive disease triggered by preterm birth?

What interventions can prevent these adverse outcomes during the neonatal period and beyond?

Is preterm birth the surrogate marker for maternal disease, which may be the key determinant of adult health?

Key points

Perinatal history is relevant across the lifespan.

Infants born preterm are at increased risk of hypertension, cardiovascular events, diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, pregnancy complications and osteoporosis later in life.

A low threshold for screening for chronic diseases in adults who were preterm infants is warranted because of the increased risks for these patients.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank François Conesa for graphic design work on Figure 1.

Footnotes

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/150450-rev

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Thuy Mai Luu drafted the initial manuscript. Sherri Katz, Paul Leeson, Bernard Thébaud and Anne-Monique Nuyt reviewed and revised the manuscript. All of the authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

References

- 1.Highlights of 2010–2011 selected indicators describing the birthing process in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isayama T, Lee SK, Mori R, et al. Comparison of mortality and morbidity of very low birth weight infants between Canada and Japan. Pediatrics 2012;130:e957–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJ, Martyn CN. The maternal and fetal origins of cardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol Community Health 1992;46:8–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, et al. Gestational age at birth and mortality in young adulthood. JAMA 2011;306:1233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crump C. Medical history taking in adults should include questions about preterm birth. BMJ 2014;349:g4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, et al. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thébaud B, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Where have all the vessels gone? Roles of angiogenic growth factors in chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:978–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueda P, Cnattingius S, Stephansson O, et al. Cerebrovascular and ischemic heart disease in young adults born preterm: a population-based Swedish cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:253–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boivin A, Luo ZC, Audibert F, et al. Pregnancy complications among women born preterm. CMAJ 2012;184:1777–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong F, Monuteaux MC, van Elburg RM, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of preterm birth and later systolic blood pressure. Hypertension 2012;59:226–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkinson JR, Hyde MJ, Gale C, et al. Preterm birth and the metabolic syndrome in adult life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1240–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards MO, Watkins WJ, Kotecha SJ, et al. Higher systolic blood pressure with normal vascular function measurements in preterm-born children. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:904–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutherland MR, Bertagnolli M, Lukaszewski MA, et al. Preterm birth and hypertension risk: the oxidative stress paradigm. Hypertension 2014;63:12–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmody JB, Charlton JR. Short-term gestation, long-term risk: prematurity and chronic kidney disease. Pediatrics 2013;131: 1168–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewandowski AJ, Davis EF, Yu G, et al. Elevated blood pressure in preterm-born offspring associates with a distinct antiangiogenic state and microvascular abnormalities in adult life. Hypertension 2015;65:607–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazdam M, de la Horra A, Pitcher A, et al. Elevated blood pressure in offspring born premature to hypertensive pregnancy: Is endothelial dysfunction the underlying vascular mechanism? Hypertension 2010;56:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly BA, Lewandowski AJ, Worton SA, et al. Antenatal glucocorticoid exposure and long-term alterations in aortic function and glucose metabolism. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1282–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewandowski AJ, Augustine D, Lamata P, et al. Preterm heart in adult life: cardiovascular magnetic resonance reveals distinct differences in left ventricular mass, geometry, and function. Circulation 2013;127:197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewandowski AJ, Bradlow WM, Augustine D, et al. Right ventricular systolic dysfunction in young adults born preterm. Circulation 2013;128:713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greig A, Constantin E, Carsley S, et al. Preventive health care visits for children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 years: The Greig Health Record — Executive Summary. Paediatr Child Health 2010;15:157–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright Futures Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents. 3rd ed Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, et al. Risk of diabetes among young adults born preterm in Sweden. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 1109–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sipola-Leppänen M, Vääräsmäki M, Tikanmäki M, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors in young adults who were born preterm. Am J Epidemiol 2015;181:861–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tinnion R, Gillone J, Cheetham T, et al. Preterm birth and subsequent insulin sensitivity: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:362–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hovi P, Andersson S, Eriksson JG, et al. Glucose regulation in young adults with very low birth weight. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2053–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kajantie E, Strang-Karlsson S, Hovi P, et al. Insulin sensitivity and secretory response in adults born preterm: the Helsinki study of very low birth weight adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singhal A, Fewtrell M, Cole TJ, et al. Low nutrient intake and early growth for later insulin resistance in adolescents born preterm. Lancet 2003;361:1089–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singhal A, Cole TJ, Fewtrell M, et al. Breastmilk feeding and lipoprotein profile in adolescents born preterm: follow-up of a prospective randomised study. Lancet 2004;363:1571–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gough A, Spence D, Linden M, et al. General and respiratory health outcomes in adult survivors of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a systematic review. Chest 2012;141:1554–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J, et al. Risk of asthma in young adults who were born preterm: a Swedish national cohort study. Pediatrics 2011;127:e913–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saigal S, Stoskopf B, Boyle M, et al. Comparison of current health, functional limitations, and health care use of young adults who were born with extremely low birth weight and normal birth weight. Pediatrics 2007;119:e562–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson AM, Doyle LW. Respiratory outcomes for the tiniest or most immature infants. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;19:105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fawke J, Lum S, Kirkby J, et al. Lung function and respiratory symptoms at 11 years in children born extremely preterm: the EPICure study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:237–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baraldi E, Bonetto G, Zacchello F, et al. Low exhaled nitric oxide in school-age children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong P, Murray C, Louw J, et al. Adult bronchopulmonary dysplasia: computed tomography pulmonary findings. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2011;55:373–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doyle LW, Faber B, Callanan C, et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight subjects and lung function in late adolescence. Pediatrics 2006;118:108–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhat R, Salas AA, Foster C, et al. Prospective analysis of pulmonary hypertension in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2012;129:e682–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hovi P, Andersson S, Jarvenpaa AL, et al. Decreased bone mineral density in adults born with very low birth weight: a cohort study. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breukhoven PE, Leunissen RW, de Kort SW, et al. Preterm birth does not affect bone mineral density in young adults. Eur J Endocrinol 2011;164:133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalziel SR, Fenwick S, Cundy T, et al. Peak bone mass after exposure to antenatal betamethasone and prematurity: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 2006; 21: 1175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]