Abstract

Lung cancer carries a poor prognosis and is the most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The integrin α6β4, a laminin receptor, promotes carcinoma progression in part by cooperating with various growth factor receptors to facilitate invasion and metastasis. In carcinoma cells with mutant TP53, the integrin α6β4 promotes cell survival. TP53 mutations and integrin α6β4 overexpression co-occur in many aggressive malignancies. Due to the high frequency of TP53 mutations in lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), we sought to investigate the association of integrin β4 expression with clinicopathologic features and survival in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We constructed a lung cancer tissue microarray and stained sections for integrin β4 subunit expression using immunohistochemistry. We found that integrin β4 expression is elevated in SCC compared to adenocarcinoma (P<0.0001), which was confirmed in external gene expression datasets (P<0.0001). We also determined that integrin β4 overexpression associates with the presence of venous invasion (P=0.0048), and with reduced overall patient survival (Hazard ratio 1.46, 95% confidence interval 1.01 to 2.09, P=0.0422). Elevated integrin β4 expression was also shown to associate with reduced overall survival in lung cancer gene expression datasets (Hazard ratio 1.49, 95% confidence interval 1.31 to 1.69, P<0.0001). Using cBioPortal, we generated a network map demonstrating the 50 most highly altered genes neighboring ITGB4 in SCC which included laminins, collagens, CD151, genes in the EGFR and PI3K pathways, and other known signaling partners. In conclusion, we demonstrate that integrin β4 is overexpressed in NSCLC where it is an adverse prognostic marker.

Keywords: Integrin signaling, cell adhesion, NSCLC, pulmonary adenocarcinoma, CD44

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States, with an estimated 158,040 deaths expected for the year 2015 [1]. Patients diagnosed with lung cancer have poor outcomes, with less than 17% of patients surviving 5 years [1]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common form of lung cancer and can be further subdivided into a variety of histologic subtypes. These subtypes include adenocarcinoma (ADC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and large cell carcinoma. Lung SCC carries a poor prognosis and is typically treated with surgical resection, radiation and traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy. While a number of targeted therapies have recently been developed for the treatment of NSCLC, these agents target genomic alterations that occur more frequently in lung ADC, such as mutations in EGFR and rearrangements of ALK and ROS1 [2, 3]. SCC remains difficult to treat in part due to a lack of targeted therapies and because of its propensity for aggressive behavior.

The integrin α6β4 is an extracellular matrix receptor that has been implicated in carcinoma progression [4, 5]. In normal epithelia, integrin α6β4 is expressed in the basal layer of cells where it binds to laminins in the extracellular matrix to nucleate the formation of stable adhesive structures termed hemidesmosomes [6]. In addition to serving an adhesive function, integrin α6β4 signaling is involved in many cellular processes including proliferation, survival, and wound healing [7–9]. The integrin β4 subunit (referred to herein as integrin β4) is particularly notable due to its long cytoplasmic signaling domain which contributes to its ability to promote invasive and metastatic behavior in cancer cells [5]. During carcinoma progression, the integrin α6β4 is released from hemidesmosomes which allows it to associate with the actin cytoskeleton [10]. Here, it activates RhoA, leading to membrane ruffling, lamellae formation and the generation of traction forces [11]. These processes enable cell migration, thus allowing the cell to invade and metastasize [12]. In addition to its effects on cell motility, the integrin α6β4 cooperates with numerous growth factor receptors including EGFR, ErbB-2, ErbB-3 and c-Met to amplify downstream signaling to pathways such as PI3K, AKT, and MAPK (for review, see [5]). The integrin α6β4 is overexpressed in a wide variety of human cancers, where in many documented cases it positively associates with poor prognosis [5].

In carcinoma cells with mutant TP53, the integrin β4 promotes cell survival [7]. Interestingly, TP53 mutations and integrin β4 overexpression co-occur in many aggressive malignancies including basal-like breast cancer, serous ovarian carcinoma, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Given that lung SCC has a high frequency of TP53 mutations, we predicted that integrin β4 expression in this tumor type would associate with aggressive behavior and poor prognosis. While integrin β4 expression in lung carcinomas has been studied previously, an association has not been demonstrated between integrin β4 overexpression and clinical outcomes [13–16]. We therefore investigated integrin β4 expression as it relates to histologic subtype, clinicopathologic features and survival in NSCLC. Here, we report that integrin β4 expression is elevated in lung SCC, and that its overexpression is associated with venous invasion and decreased overall survival in patients with NSCLC.

Materials and Methods

Lung cancer tissue microarray (TMA) construction

This project was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board (13-0692-P6H). Surgically resected NSCLC cases were identified using natural language searches in CoPath (Cerner Corporation, Kansas City, MO). After review, a total of 216 cases were selected for inclusion in the TMAs. These represented an assortment of histologic subtypes, including 83 ADCs, 102 SCCs, 12 adenosquamous carcinomas, 12 poorly differentiated carcinomas, 2 large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, 1 giant cell carcinoma, 1 pleomorphic carcinoma, 2 tumors with mixed histology (mixed ADC and large cell neuroendocrine) and 1 sarcomatoid carcinoma. Prior to selection for the TMA, each case was reviewed by a board-certified pathologist and clinicopathologic features (tumor grade, tumor size, histologic type, pTNM staging, presence of lymphovascular, venous, and pleural invasion) were recorded using cancer templates. Only primary lung cancers were included, and cases were excluded if there was inadequate pathologic material available. Original hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides were reviewed and appropriate tumor blocks were selected from each case. Fresh H&E stained sections were then cut from each selected tumor block and then reviewed by the team pathologist to identify tumor areas for inclusion in the TMA. Pathologic features were abstracted from pathology records and cancer templates using Cerner CoPath Plus v2013.01.1.070 (Cerner Corporation, Kansas City MO). Outcome data were collected by the Cancer Research Informatics Shared Resource Facility. Samples were randomly sorted by stage for allocation into the recipient TMA by the MCC Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource Facility, and TMAs were constructed by the MCC Biospecimen and Tissue Procurement Shared Resource Facility. Three 2 mm diameter tissue cores were obtained from each tumor specimen, which were then transferred to recipient paraffin blocks (12 blocks) using a TMArrayer (Pathology Devices, Westminster, MD). Sections used for integrin β4 immunohistochemistry had interpretable tissue cores in 211/216 cases. Patient characteristics for these 211 cases are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| N (% total) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Age, mean (range years) | 63 (range 39–84) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 88 | (42%) |

| Male | 123 | (58%) |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Total available | 159 | |

| Smoker | 154 | (97%) |

| Never smoker | 5 | (3%) |

| Residence | ||

| Appalachian | 145 | (69%) |

| Non-Appalachian | 59 | (28%) |

| Out of state | 7 | (3%) |

| Vital Status | ||

| Alive | 89 | (42%) |

| Deceased | 122 | (58%) |

| Tumor characteristics | ||

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 81 | (38%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 99 | (47%) |

| Other | 31 | (15%) |

| Differentiation | ||

| Well | 12 | (6%) |

| Moderate | 87 | (41%) |

| Poor | 112 | (53%) |

| AJCC Stage | ||

| I | 108 | (51%) |

| II | 37 | (18%) |

| III | 44 | (21%) |

| IV | 13 | (6%) |

| Unknown | 9 | (4%) |

| Total | 211 | |

Immunohistochemical staining

TMA sections (4 µm) were stained using a rat monoclonal primary antibody to the integrin β4 subunit (CD 104) (clone 439-9B; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) at a concentration of 1:200 according to a previously described protocol [17]. Integrin β4 expression was scored by a pathologist using a semiquantitative scale as follows: negative (0), weak (1), moderate (2), and strong (3). Scoring was performed while blinded to clinical variables and outcome. Results from each of the three tissue cores were averaged to produce a final score for each patient.

Data Mining

Multiple lung cancer gene expression datasets were analyzed for ITGB4 mRNA expression. The first of these was a NSCLC dataset generated by the Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (TCGA, http://cancergenome.nih.gov/) containing 155 SCC samples and 32 ADC samples that were analyzed using a custom Agilent microarray. The second was a dataset generated by Hou et al. containing 91 NSCLCs and 65 adjacent normal lung samples that had been analyzed using a Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) [18]. These datasets were viewed and downloaded using The Oncomine™ Platform v4.5 (Life Technologies, Ann Arbor, MI). The UCSC Cancer Browser (https://genome-cancer.ucsc.edu/proj/site/hgHeatmap/) was used to visualize and download a processed lung SCC gene expression dataset (N = 155) in order to identify genes correlated with ITGB4 [19, 20]. In addition, cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/) was used to generate a network map showing the 50 most highly altered genes neighboring ITGB4 in the TCGA lung SCC dataset [21, 22]. In order to investigate integrin β4 gene expression as it relates to patient survival, we analyzed a NSCLC gene expression database using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter [23] (N = 1,926) (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) where overall patient survival was analyzed using a median cutoff and the 2015 version of the database.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed using Fisher's exact test, two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction, or one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test, as appropriate. Survival differences were assessed via log-rank tests for univariate analyses. Significance was reached when P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, Version 5.01 (Graph Pad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA) and using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter [23].

Results

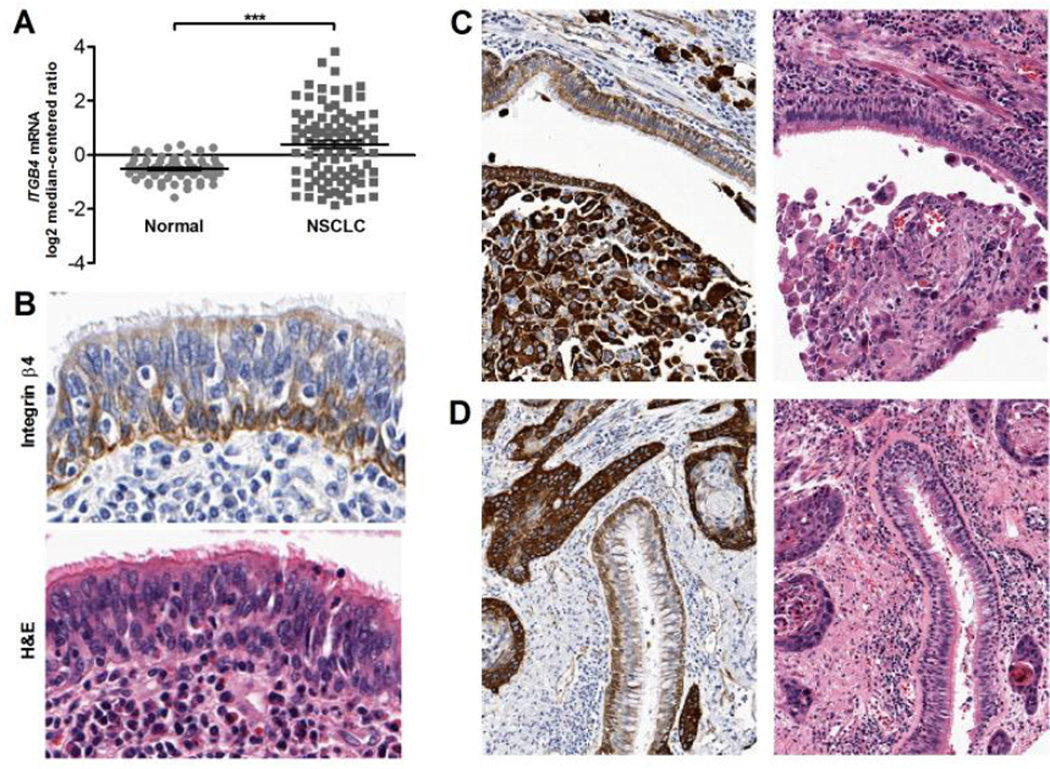

Integrin β4 expression is elevated in NSCLC compared to normal lung tissue

In order to examine integrin β4 expression across a large number of patient-derived samples, we constructed and utilized a lung cancer TMA and analyzed external gene expression datasets. In the Hou external dataset, NSCLCs were found to have elevated integrin β4 expression when compared to normal lung tissue (Fig. 1A; P <0.0001), which we also observed in our TMA. Although normal lung tissue was not specifically selected for inclusion in the TMA, benign bronchial epithelium was identified adjacent to invasive carcinoma cells in a subset of tissue cores. As shown in Figure 1B, integrin β4 was primarily expressed in basal cells and along the basement membrane of lung pseudostratified columnar epithelium. Weak staining was also present at the apical surface of ciliated columnar cells, while goblet cells and immune cells in the bronchial epithelium were negative for integrin β4 expression. Notably, integrin β4 expression was higher in the invasive carcinoma (Fig. 1C–D) than in adjacent benign bronchial epithelium. In addition, basal polarization of integrin β4 expression was lost in invasive carcinoma.

Figure 1. Expression of integrin β4 in benign lung.

In the Hou dataset, NSCLCs had greater average levels of ITGB4 mRNA than normal lung, P < 0.0001 via two-tailed t-test with Welch's correction (A). In benign bronchial epithelium, integrin β4 was expressed in basal cells and along the basement membrane, with weak expression at the apical surface of ciliated columnar cells (B). However, in invasive carcinoma, integrin β4 expression was significantly more intense in carcinoma cells than in adjacent benign bronchial epithelium (C, D). Magnification is 200× for all images.

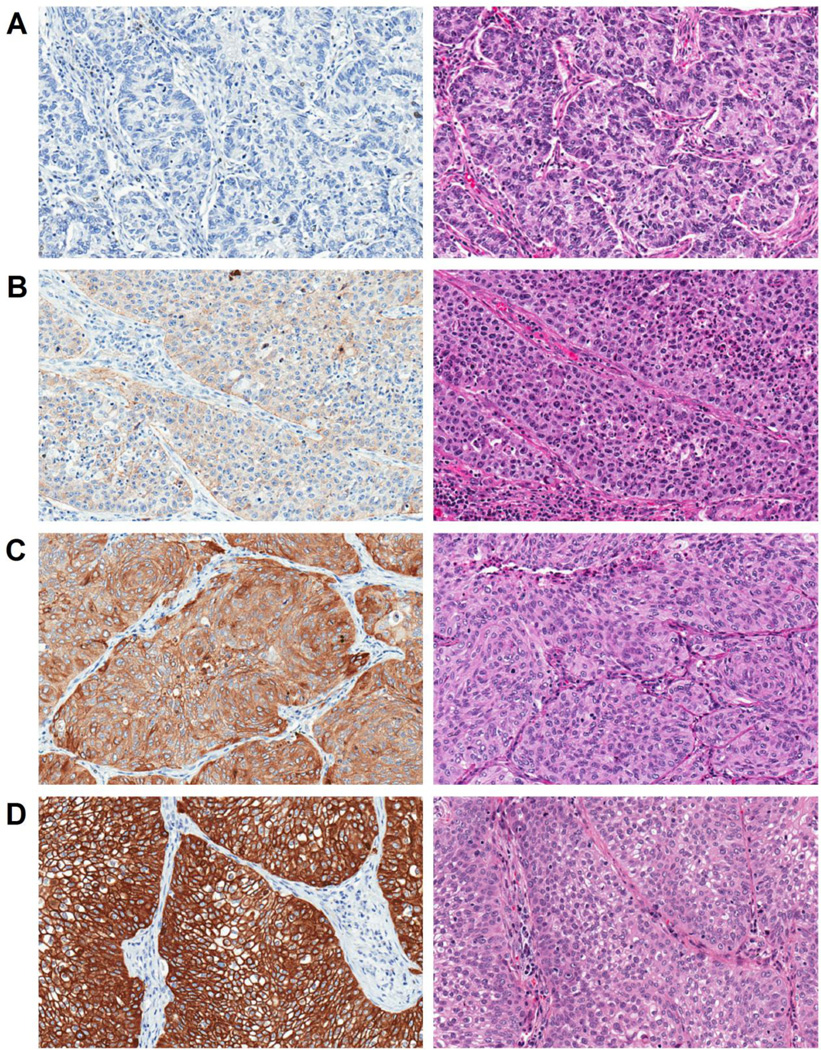

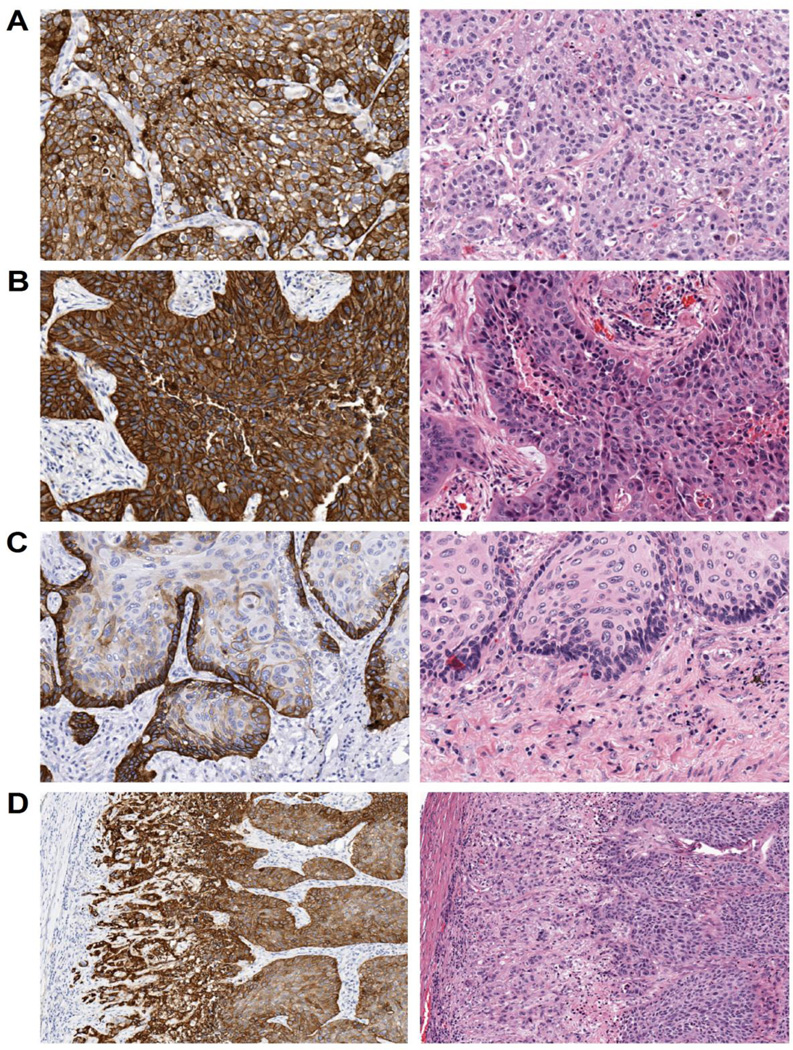

Altered localization of the integrin β4 in NSCLC

Integrin β4 expression was found to be highly variable in NSCLCs with some cases exhibiting strong and diffuse staining, while others were completely negative for integrin β4 expression. Staining was scored by a pathologist using a semiquantitative scale as follows: negative (0), weakly positive (1), moderately positive (2), and strongly positive (3) (Fig. 2A–D). In select tumors, staining was predominantly membranous, while others exhibited a mixture of cytoplasmic and membranous immunoreactivity (Fig. 3A–B). Integrin β4 staining intensity was elevated at the tumor-stromal interface in some tumors (Fig. 3C), a phenomenon that has been previously described by others [14]. Individual infiltrating tumor cells and nests at the invasive front also tended to have elevated integrin β4 expression compared to cells at the center of the tumor (Fig. 3D).

Figure 2. Integrin β4 staining intensity in NSCLC.

Examples of negative (0) (A), weak (1) (B), moderate (2) (C), and strong (3) (D) integrin β4 expression in NSCLCs. Left panels show integrin β4 staining, right show H&E. Magnification is 200× for all images.

Figure 3. Localization of integrin β4 staining in NSCLC.

Select NSCLC cases exhibited predominantly membranous staining (A), while others had strong membranous and cytoplasmic expression of the integrin β4 (B). In some cases, integrin β4 was elevated at the tumor-stroma interface (C), and at the invasive front of tumors (D). Magnification is 200× for A–C, and 100× for D.

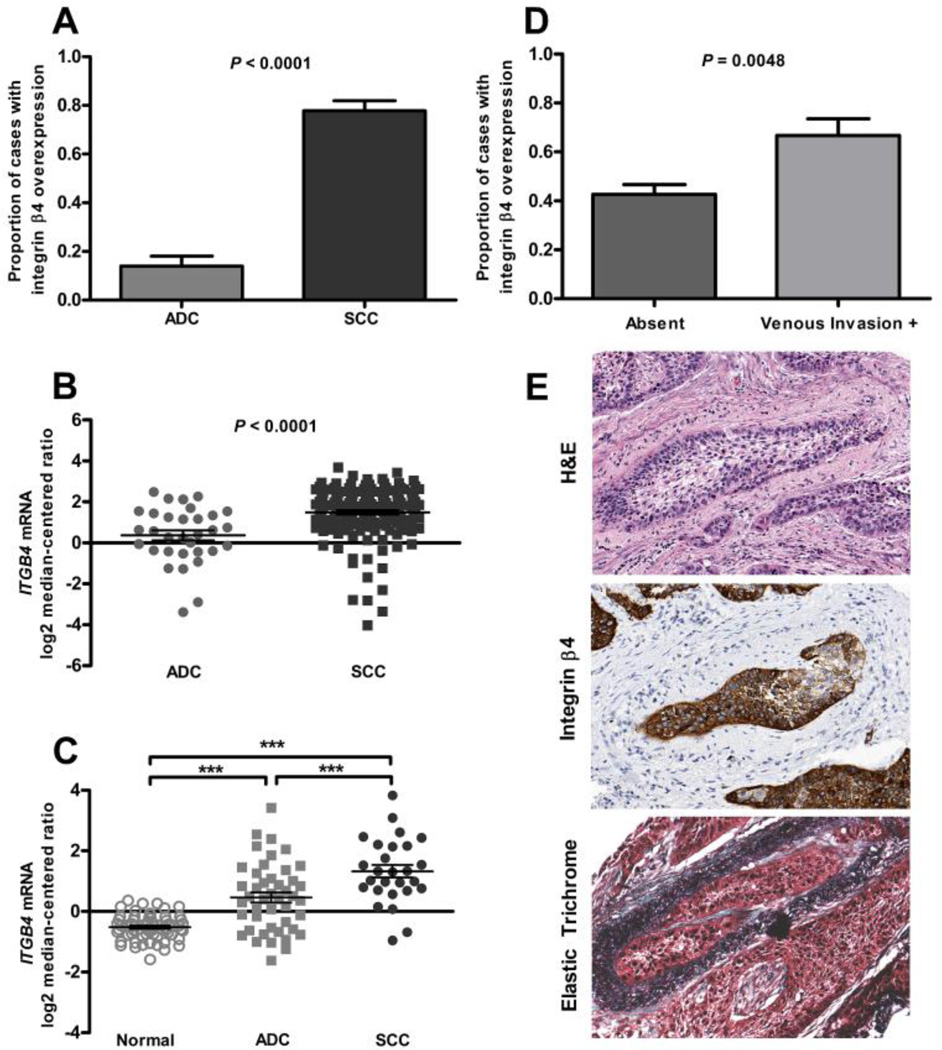

Elevated integrin β4 expression associates with venous invasion and an adverse prognosis in NSCLC

To decipher how integrin β4 associates with clinical features, we first compared integrin β4 expression between histologic subtypes. Individual tissue cores from our TMA were scored by a pathologist and the values for each patient averaged; patients with an average integrin β4 IHC score of ≥ 2.5 were considered to have elevated expression. In our TMA cohort, integrin β4 was elevated in SCC when compared to ADC (Fig. 4A; P < 0.0001); this finding was confirmed in two external gene expression datasets including those from TCGA and from Hou et al. [18, 19] (Fig. 4B–C; P < 0.0001). Integrin β4 protein expression was also elevated in a subset of adenosquamous carcinomas and poorly differentiated tumors that were evaluated in our TMA (Table 2). Using data abstracted from pathology reports, we found that integrin β4 overexpression was associated with the presence of venous invasion (Fig. 4D–E; P = 0.0048).

Figure 4. Integrin β4 expression in NSCLC by histologic subtype and association with venous invasion.

SCCs had a higher proportion of cases with elevated integrin β4 expression than did adenocarcinomas, as measured using semi-quantitative IHC, P < 0.0001 via Fisher’s exact test (A). In the TCGA dataset, average ITGB4 mRNA expression was higher in SCCs than in adenocarcinomas, P < 0.0001 via two-tailed t test with Welch's correction (B). In the Hou dataset, average ITGB4 mRNA expression was higher in SCCs when compared to both normal lung tissue and adenocarcinomas, P < 0.0001 via one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test (C). Integrin β4 overexpression was associated with the presence of venous invasion, P = 0.0048 via Fisher’s exact test (D). An example of a tumor from the TMA with venous invasion, stained with H&E, integrin β4 and elastic trichrome, as noted (E). Magnification is 200× for all images.

Table 2.

Integrin β4 expression in NSCLC by histologic subtype.

| Integrin β4 High | Integrin β4 Low | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 101/211 (48%) | 110/211 (52%) |

| Histologic Type: | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 77/99 (78%) | 22/99 (22%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 11/81 (14%) | 70/81 (86%) |

| Other histologic types: | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 5/12 (42%) | 7/12 (58%) |

| Adenosquamous | 7/12 (58%) | 5/12 (42%) |

| Mixed histology | 1/2 (50%) | 1/2 (50%) |

| Large cell neuroendocrine | 0/2 (0%) | 2/2 (100%) |

| Pleomorphic carcinoma | 0/1 (0%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| Giant cell carcinoma | 0/1 (0%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| Sarcomatoid carcinoma | 0/1 (0%) | 1/1 (100%) |

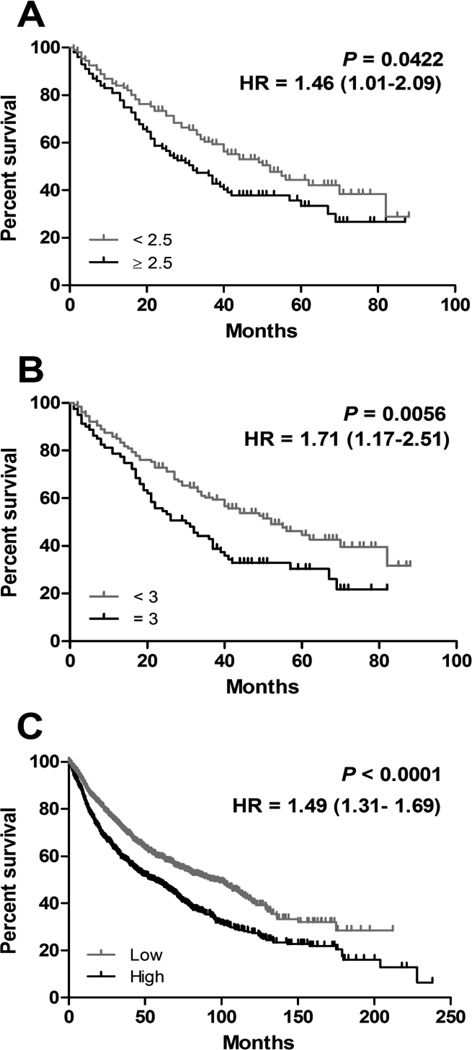

To date, no data have been published that demonstrate an association between integrin β4 expression and patient outcome in NSCLC. In our TMA cohort, integrin β4 overexpression (score ≥ 2.5) was significantly associated with shorter overall survival (Fig 5A; hazard ratio 1.46, 95% confidence interval 1.01 to 2.09, P = 0.0422). This relationship was also significant when using a higher cutoff point (score = 3) to define integrin β4 overexpression (Fig. 5B; hazard ratio 1.71, 95% confidence interval 1.17 to 2.51, P = 0.0056). In addition, elevated integrin β4 expression was shown to associate with reduced overall survival in a NSCLC gene expression dataset (Fig. 5C; N = 1,926; Hazard ratio 1.49, 95% confidence interval 1.31 to 1.69, P<0.0001).

Figure 5. Integrin β4 and survival in NSCLC.

In our TMA cohort, elevated expression of integrin β4 was associated with shorter median overall survival, P = 0.0422 (A) and P = 0.0056 (B). Using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter, elevated integrin β4 expression was also shown to associate with reduced overall survival (P<0.0001) in a NSCLC gene expression database (C).

Integrin β4 associated genes

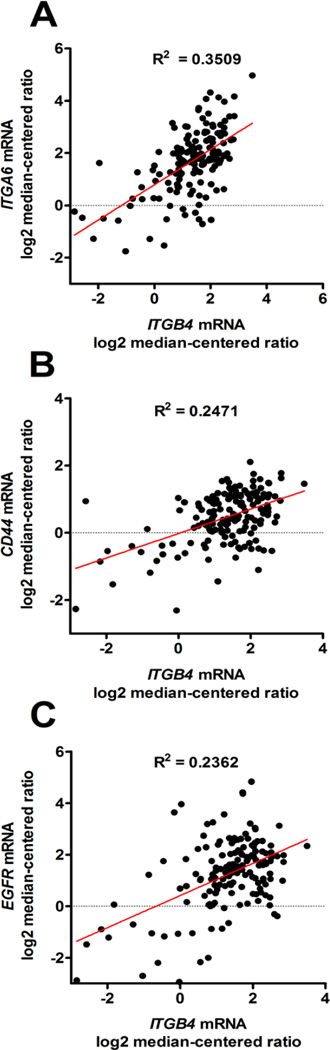

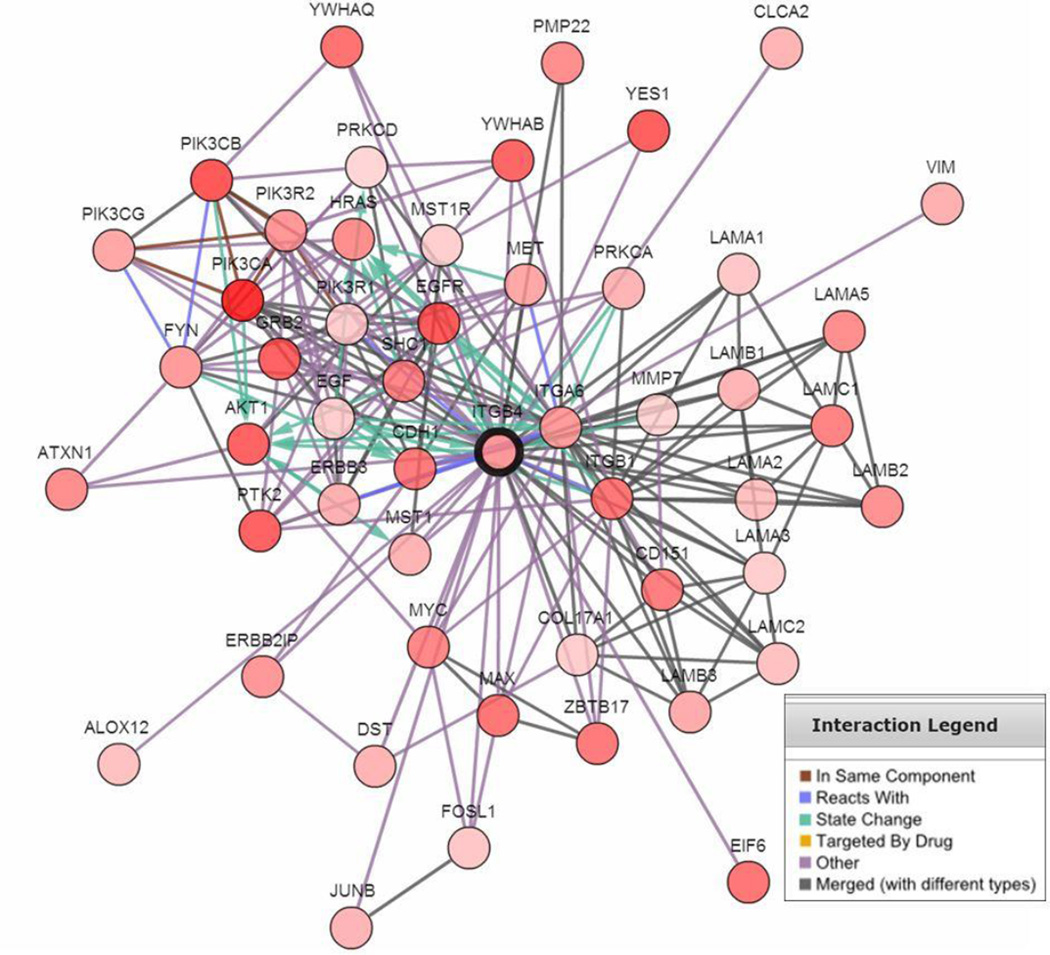

In order to explore signaling pathways and gene expression pattens that may associate with integrin β4 in lung cancer, cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/) was used to generate a list of the top 50 genes most positively correlated with ITGB4 in lung SCC. We found that ITGB4 was highly correlated with that of its binding partner ITGA6, as well as that of CD44 (Fig. 6A–B; P < 0.0001), both of which are markers of cancer stem cells [24]. ITGB4 was also highly correlated with EGFR expression (Fig. 6C; P < 0.0001). We further generated a network map using cBioPortal that demonstrates highly altered genes neighboring ITGB4 (Fig. 7). These genes included laminins (LAMA1, LAMA3, LAMB1, LAMB3, LAMC1, LAMC2, etc), other integrin subunits (ITGA6, ITGB1), tetraspanin CD151, genes in the EGFR family (EGF, EGFR, ERBB3), genes in the PI3K pathway (PIK3CA, AKT1), and other known signaling partners (MET, FYN).

Figure 6. ITGB4 expression correlates with ITGA6, CD44, and EGFR in SCC.

By linear regression, ITGB4 mRNA expression levels positively correlated with ITGA6 (A), CD44 (B), and EGFR (C).

Figure 7. Network map illustrating highly altered genes associated with ITGB4.

In this network map, ITGB4 is connected to laminins (LAMA1, LAMB1, LAMC1, LAMA2, etc), genes in the EGFR family (EGFR, ERBB3), genes in the PI3K pathway (PIK3CA, AKT1), other integrins (ITGA6, ITGB1), stem cell markers (CD44, ITGA6) and the tetraspanin CD151.

Discussion

In this study, we show that integrin β4 is highly expressed in lung SCC, and that its overexpression is associated with venous invasion and reduced overall survival in NSCLC. Particularly notable is the finding that integrin β4 localization is altered in invasive lung cancer. In benign epithelia, the integrin β4 is located at the basal aspect of cells at their junction with the extracellular matrix. However, during carcinoma progression, the integrin β4 is released from hemidesmosomes where it can accumulate at the leading edge of the cell. Here, the integrin associates with the actin cytoskeleton where it can then contribute to cell migration, thus allowing the cell to invade and metastasize. We found that in benign bronchial epithelium, expression of the integrin β4 is basally located; however, in invasive carcinoma, integrin β4 is redistributed over the cell surface, consistent with its role in invasion and migration. In addition, we found that integrin β4 staining is elevated at the invasive front of tumors and at the tumor-stromal interface. These findings underscore the importance of the integrin β4 in contributing to an invasive phenotype in NSCLC.

Our data support previous studies regarding integrin α6β4 and lung cancer progression. Early reports demonstrated that expression of the integrin α6β4 (previously described as TSP-180) is elevated in murine Lewis lung carcinoma variants with high metastatic potential [25]. Multiple studies investigating integrin β4 expression in patient-derived tissues have shown that it is expressed in NSCLC, with high levels observed in SCC [13–15]. A more recent study using gene expression profiling identified differentially expressed genes in samples of pulmonary ADC, SCC, and normal bronchus, where they found that integrin β4 was significantly upregulated in SCC [16]. Notably, the integrin β4 gene (ITGB4) is upregulated in the basal molecular subtype of lung SCC as defined using unsupervised clustering of gene expression microarray data [26].

By studying external gene expression datasets, we found that expression of the integrin β4 gene is positively correlated with expression of the cancer stem cell marker, CD44. CD44 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that has been shown to facilitate many aspects of tumor progression and is important in promoting resistance to therapy [27, 28]. Interestingly, integrin β4 has been implicated in promoting stem cell like properties in breast cancer [29], and has been identified in the cancer stem cell population in NSCLC [30]. In addition, we found that expression of the integrin β4 gene is correlated with that of its binding partner, integrin α6 (CD49f), a known stem cell marker [31]. In the network map, integrin β4 is connected to a number of laminin subunits (LAMA3, LAMB3, LAMC2), which is consistent with the fact that integrin β4 binds laminins in the extracellular matrix. Interestingly, the laminins most well studied in reference to integrin α6β4 including laminin-1 (composed of LAMA1, LAMB1, LAMC1) and laminin-5 (which includes LAMA3, LAMB3, LAMC2) are most prominent. Also notable was the connection between integrin β4 and COL17A1, (Collagen, Type XVII, Alpha 1), as this gene encodes the BP180 protein that is necessary for hemidesmosome assembly.

Integrin β4 cooperates with a variety of growth-factor receptors to amplify proliferative and invasive signaling. We found that integrin β4 gene expression was positively correlated with that of EGFR, and in the network map, integrin β4 was connected to genes in the EGFR signaling pathway. These findings are notable in light of evidence demonstrating a functional relationship between EGFR and integrin β4 [32, 33]. In particular, integrin β4 has been shown to interact with EGFR in lipid rafts where it enhances cell growth and proliferation [34]. Furthermore, our lab has demonstrated that in pancreatic carcinoma cells, integrin α6β4 promotes autocrine EGFR signaling [35].

As the integrin β4 can promote invasion, proliferation, and stem cell-like properties, it is not surprising that elevated integrin β4 expression is associated with poor prognosis. We found that elevated integrin β4 expression is a marker of poor prognosis for patients with lung cancer, both in our TMA cohort as well as in external gene expression datasets. These data are in agreement with previous studies demonstrating an association between integrin β4 expression and poor prognosis in other cancer types [5]. In addition, we found an association between elevated integrin β4 expression and the presence of venous invasion. Venous invasion has been associated with recurrence and poor prognosis in lung and colorectal carcinoma [36].

In summary, we demonstrate that integrin β4 is elevated in NSCLCs compared to normal lung tissue, and that it is preferentially overexpressed in lung SCC. Furthermore, integrin β4 positively associates with the presence of venous invasion and reduced survival in patients as evidenced from analysis of our TMA and external cohorts.

Acknowledgments

The Markey Cancer Center Biospecimen and Tissue Procurement and the Biostatistics Shared Resources Facilities facilitated the construction of tissue microarrays, and the Cancer Research Informatics Shared Resource Facility assisted with clinical annotations (P30CA177558). Special thanks to Dana Napier for her expertise in TMA construction. We gratefully acknowledge Zobeida Cruz-Monserrate and Linda Muehlberger for their assistance with the integrin β4 immunohistochemistry protocol. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants T32 CA160003 (RLS), R01 CA109136 (KLO), the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000117 (MC), the American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant IRG-85-001-25 (MC), and by the Dr. Joseph F. Pulliam Pilot Award (MC and RLS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/, based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crino L, Ahn MJ, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385–2394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo W, Giancotti FG. Integrin signalling during tumour progression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:816–826. doi: 10.1038/nrm1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart RL, O'Connor KL. Clinical significance of the integrin alpha6beta4 in human malignancies. Lab Invest. 2015;95:976–986. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stepp MA, Spurr-Michaud S, Tisdale A, Elwell J, Gipson IK. Alpha 6 beta 4 integrin heterodimer is a component of hemidesmosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:8970–8974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachelder RE, Ribick MJ, Marchetti A, Falcioni R, Soddu S, Davis KR, et al. p53 inhibits alpha 6 beta 4 integrin survival signaling by promoting the caspase 3-dependent cleavage of AKT/PKB. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1063–1072. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mainiero F, Murgia C, Wary KK, Curatola AM, Pepe A, Blumemberg M, et al. The coupling of alpha6beta4 integrin to Ras-MAP kinase pathways mediated by Shc controls keratinocyte proliferation. EMBO J. 1997;16:2365–2375. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikolopoulos SN, Blaikie P, Yoshioka T, Guo W, Puri C, Tacchetti C, et al. Targeted deletion of the integrin beta4 signaling domain suppresses laminin-5-dependent nuclear entry of mitogen-activated protein kinases and NF-kappaB, causing defects in epidermal growth and migration. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6090–6102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6090-6102.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabinovitz I, Mercurio AM. The integrin alpha6beta4 functions in carcinoma cell migration on laminin-1 by mediating the formation and stabilization of actin-containing motility structures. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1873–1884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Connor KL, Nguyen BK, Mercurio AM. RhoA function in lamellae formation and migration is regulated by the alpha6beta4 integrin and cAMP metabolism. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:253–258. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connor K, Chen M. Dynamic functions of RhoA in tumor cell migration and invasion. Small GTPases. 2013;4:141–147. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.25131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariani Costantini R, Falcioni R, Battista P, Zupi G, Kennel SJ, Colasante A, et al. Integrin (alpha 6/beta 4) expression in human lung cancer as monitored by specific monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6107–6112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koukoulis GK, Warren WH, Virtanen I, Gould VE. Immunolocalization of integrins in the normal lung and in pulmonary carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patriarca C, Alfano RM, Sonnenberg A, Graziani D, Cassani B, de Melker A, et al. Integrin laminin receptor profile of pulmonary squamous cell and adenocarcinomas. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boelens MC, van den Berg A, Vogelzang I, Wesseling J, Postma DS, Timens W, et al. Differential expression and distribution of epithelial adhesion molecules in non-small cell lung cancer and normal bronchus. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:608–614. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.031443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruz-Monserrate Z, Qiu S, Evers BM, O'Connor KL. Upregulation and redistribution of integrin alpha6beta4 expression occurs at an early stage in pancreatic adenocarcinoma progression. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:656–667. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou J, Aerts J, den Hamer B, van Ijcken W, den Bakker M, Riegman P, et al. Gene expression-based classification of non-small cell lung carcinomas and survival prediction. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cline MS, Craft B, Swatloski T, Goldman M, Ma S, Haussler D, et al. Exploring TCGA Pan-Cancer Data at the UCSC Cancer Genomics Browser. Scientific Reports. 2013;3 doi: 10.1038/srep02652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao JJ, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Science Signaling. 2013;6 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gyorffy B, Surowiak P, Budczies J, Lanczky A. Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali HR, Dawson SJ, Blows FM, Provenzano E, Pharoah PD, Caldas C. Cancer stem cell markers in breast cancer: pathological, clinical and prognostic significance. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R118. doi: 10.1186/bcr3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacchi A, Falcioni R, Piaggio G, Gianfelice MA, Perrotti N, Kennel SJ. Ligand-induced phosphorylation of a murine tumor surface protein (TSP-180) associated with metastatic phenotype. Cancer Res. 1989;49:2615–2620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkerson MD, Yin X, Hoadley KA, Liu Y, Hayward MC, Cabanski CR, et al. Lung squamous cell carcinoma mRNA expression subtypes are reproducible, clinically important, and correspond to normal cell types. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4864–4875. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu CM, Chang CH, Yu CH, Hsu CC, Huang LL. Hyaluronan substratum induces multidrug resistance in human mesenchymal stem cells via CD44 signaling. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;336:465–475. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0780-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ponta H, Sherman L, Herrlich PA. CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:33–45. doi: 10.1038/nrm1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vieira AF, Ribeiro AS, Dionisio MR, Sousa B, Nobre AR, Albergaria A, et al. P-cadherin signals through the laminin receptor alpha 6 beta 4 integrin to induce stem cell and invasive properties to basal-like breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2014;5:679–692. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng Y, de la Cruz CC, Sayles LC, Alleyne-Chin C, Vaka D, Knaak TD, et al. A rare population of CD24(+)ITGB4(+)Notch(hi) cells drives tumor propagation in NSCLC and requires Notch3 for self-renewal. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu KR, Yang SR, Jung JW, Kim H, Ko K, Han DW, et al. CD49f enhances multipotency and maintains stemness through the direct regulation of OCT4 and SOX2. Stem Cells. 2012;30:876–887. doi: 10.1002/stem.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabinovitz I, Toker A, Mercurio AM. Protein kinase C-dependent mobilization of the alpha6beta4 integrin from hemidesmosomes and its association with actin-rich cell protrusions drive the chemotactic migration of carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1147–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mainiero F, Pepe A, Yeon M, Ren YL, Giancotti FG. The intracellular functions of alpha(6)beta(4) integrin are regulated by EGF. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;134:241–253. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gagnoux-Palacios L, Dans M, van't Hof W, Mariotti A, Pepe A, Meneguzzi G, et al. Compartmentalization of integrin alpha6beta4 signaling in lipid rafts. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1189–1196. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter BL, Chen M, Knifley T, Davis KA, Harrison SM, Stewart RL, et al. Integrin alpha6beta4 Promotes Autocrine Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Signaling to Stimulate Migration and Invasion toward Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27228–27238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.686873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimada Y, Saji H, Yoshida K, Kakihana M, Honda H, Nomura M, et al. Pathological vascular invasion and tumor differentiation predict cancer recurrence in stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer after complete surgical resection. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1263–1270. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31825cca6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]