Abstract

This study evaluated the influence of child and family functioning on child sleep behaviors in low-income minority families who are at risk for obesity. A cross-sectional study was utilized to measure child and family functioning from 2013 to 2014. Participants were recruited from Head Start classrooms while data were collected during home visits. A convenience sample of 72 low-income Hispanic (65%) and African American (32%) families of preschool aged children. We assessed the association of child and family functioning with child sleep behaviors using a multivariate multiple linear regression model. Bootstrap mediation analyses examined the effects of family chaos between child functioning and child sleep problems. Poorer child emotional and behavioral functioning related to total sleep behavior problems. Chaos associated with bedtime resistance, Chaos significantly mediated the relationship between BESS and Bedtime Resistance. Families at high risk for obesity showed children with poorer emotional and behavioral functioning were at higher risk for problematic sleep behaviors, although we found no link between obesity and child sleep. Family chaos appears to play a significant role in understanding part of these relationships. Future longitudinal studies are necessary to establish causal relationships between child and family functioning and sleep problems to further guide obesity interventions aimed at improving child sleep routines and increasing sleep duration.

Keywords: sleep problems, preschool, bedtime resistance, obesity, minority

The prevalence of obesity among US children aged 2–5 years remains significantly high and disproportionate across income, race and ethnicity (May et al., 2013; Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2014). The relationship between race and ethnicity and obesity has been shown to exist after accounting for differences in SES (Wang & Zhang, 2006). Compared to non-Hispanic white preschoolers (3.5%), the prevalence of obesity in African American children was more than 3 times higher (11.3%) and Hispanic children had rates nearly 5 times as high (16.7%). Beyond diet and activity, child sleep problems have emerged as novel, modifiable risk factors for obesity (Haines et al., 2013). Short sleep duration has been identified as a strong predictor, independent of other obesity risk factors, and most consistently during early childhood (Chen, Beydoun, & Wang, 2008). Longitudinal studies with preschoolers identified 4 distinct sleep trajectories and short sleep duration was found to be predictive of being overweight and poorer physical health (Magee, Gordon, & Caputi, 2014; Touchette et al., 2007). Physiologically, short sleep duration has been associated with increased ghrelin and decreased leptin, in which hormonal changes have been linked with increased appetite (Taheri, Lin, Austin, Young, & Mignot, 2004). Beyond sleep duration, specific sleep behaviors may have relevance to linking sleep with weight status. For instance, bedtime resistance has been linked with poor bedtime practices, particularly among children with difficult temperaments. Sleep disturbances and delayed sleep onset have also related to reduced sleep duration and increased weight status (Jarrin, McGrath, & Drake, 2013; Wilson, Miller, Bonuck, Lumeng, & Chervin, 2014). The literature remains limited, however, on clarifying the role of individual, familial, and environmental factors that may directly or indirectly impact child sleep problems among children at risk for obesity. Moreover, research on this topic remains limited on children and families who are difficult to recruit and at higher risk for health problems. Specifically, family functioning and child emotional and behavioral factors may provide further understanding about sleep problems for children at risk for obesity (Hale, Berger, LeBourgeois, & Brooks-Gunn, 2011).

Family Functioning

Family context provides an important framework when considering child sleep and health outcomes (Dahl & El-Sheikh, 2007). Multiple factors of family functioning have been linked with child sleep problems, including parental sleep quality, stress, and fatigue (Meltzer & Mindell, 2007); marital conflict (El-Sheikh, Buckhalt, Mize, & Acebo, 2006); and maternal sleep and psychological functioning (Bajoghli, Alipouri, Holsboer-Trachsler, & Brand, 2013). Family chaos may represent an additional construct that may impact child sleep. Family chaos has been defined as family disorganization, and as environments that are unstructured, pressured for time, noisy, and unpredictable (Matheny, Wachs, Ludwig, & Phillips, 1995). Family chaos has been shown to be an independent predictor of poor functioning for children and parents, controlling for demographic characteristics and parenting stress (Dumas et al., 2005). A socioecological framework conceptualizes a child within a family and the causal arrows of child and family factors may be bi-directional, though empirical evidence supports family chaos as a mediating variable for child problem behaviors (Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Evans, Gonnella, Marcynyszyn, Gentile, & Salpekar, 2005). Regarding risk for obesity, Appelhans and colleagues recruited low-income families (18% Hispanic) and found a significant positive relationship between family chaos and child weight status that was mediated by short sleep duration and higher screen time (Appelhans et al., 2014). While the study provided initial evidence linking family chaos with sleep duration, other important factors were not assessed, including child emotional and behavioral problems.

Child Functioning

Child factors that influence bedtime problems related to sleep duration include difficult temperaments and emotional and behavioral problems (Wilson, Lumeng, et al., 2014). A large (n=8950), longitudinal study indicated that over-activity, anger, aggression, impulsivity, tantrums, and annoying behaviors predicted shorter sleep duration, (Scharf, Demmer, Silver, & Stein, 2013). Bedtime resistance problems, (verbal and behavioral resistance to entering and staying in bed), are common among young children, ranging in prevalence from 20% to 30% and have been linked to childhood obesity (Lozoff, Wolf, & Davis, 1985; Morgenthaler et al., 2006). Longitudinal evidence during early childhood showed that without intervention, bedtime problems often persist from infancy through early preschool ages (Byars, Yolton, Rausch, Lanphear, & Beebe, 2012). Bedtime resistance may impact overall sleep duration and result in increased risk for obesity. Poor sleep during childhood has been associated with reduced cognitive performance, lower quality of life, and secondary effects including impaired family functioning (Chen et al., 2008; Lavigne et al., 1999; Magee et al., 2014). The relationships between child functioning and specific sleep problems in children at high risk for obesity remains unclear in the extant literature.

Bedroom Environment Factors

The availability of televisions (TVs) in child bedrooms has been associated with increased screen time use (Christakis, Ebel, Rivara, & Zimmerman, 2004). In an ethnically/racially diverse sample of 184 parents with children ages 3 months to 12 years, 72% of the parents reported having a television in the child’s sleep environment (Owens & Jones, 2011). The presence of a screen in the bedroom has been linked with later sleep onset and shorter sleep duration among school aged children (Must & Parisi, 2009; Van den Bulck, 2004). Emerging evidence with preschool aged children showed significant relationships with televisions in bedrooms, increased screen time, reduced sleep duration, and increased weight status (Appelhans et al., 2014). Given the link between obesity, higher screen time, and a television in bedrooms, additional studies are needed to clarify how TVs in bedrooms interact with family and child functioning in relation to child sleep problems.

This investigation tested a model based on ecological theory, by which individual, family, and environmental factors were included as factors impacting child sleep problem behaviors (Story, Kaphingst, Robinson-O’Brien, & Glanz, 2008). The overall goals were to test the cross-sectional relationship between child emotional and behavioral functioning and sleep problems, and the effects of family functioning and sleeping environment in a sample of preschool aged children from low-income and racial/ethnic minority families. Poorer family and child functioning were predicted to independently predict greater child sleep problems. Further, family functioning was hypothesized to mediate the relationship between child emotional and behavioral functioning and sleep outcomes.

Method

Participants and Procedures

A sample of 75 parent-child dyads were recruited from Head Start centers in the Denver, CO region. Head Start centers provided a basis to recruit low-income families based on general eligibility for Head Start to include family income at or below the poverty level. Eligibility for parents included being self-identified as African-American or Hispanic (English or Spanish speaking), at least 18 years of age, and having a child between the ages of 3 and 5 years old. Parents were approached during arrival at Head Start centers and given a brief description of the study. Interested parents provided contact information and later completed a screening phone call to determine eligibility. A home visit was then scheduled to obtain consent and to administer assessments. Upon completion of assessments, participants received a $40 gift card to a local grocery store. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board for protection of human subjects approved this study.

Measures

Demographics

Each parent provided parent and child age and race/ethnicity, education, and family income.

Height and Weight

Child and parent weight and height were measured with standard anthropometric procedures (digital SECA 770 portable scale and SECA 214 portable stadiometer). BMI (kg/m2) and child zBMI were calculated based on standardized growth charts based on normed sex and age specific population references (Kuczmarski et al., 2000).

Sleep Functioning

Parents completed the Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), validated for use with preschool aged children (Sneddon, Peacock, & Crowley, 2013). The CSHQ is a 30 item questionnaire about child sleep habits including: bedtime resistance, sleep onset delay, sleep duration, sleep anxiety, night wakings, parasomnias, sleep disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness (Owens, Spirito, & McGuinn, 2000). Alpha coefficients for the present data indicated adequate scale reliability only for Total Score (.79), Bedtime Resistance (.74), Poor Sleep Duration (.62), Sleep Anxiety (.63), and Night Wakings (.70) (Kline, 2011). Therefore, the remaining CSHQ subscales were not further analyzed.

Additionally, parents completed a 7-day Sleep Diary. Parent-reported sleep diaries for preschool aged children have been shown to be reliably similar to actigraphy with regard to sleep start and end times and total duration (Werner, Molinari, Guyer, & Jenni, 2008). Total parent reported duration of nighttime sleep was calculated by subtracting the difference between the sleep and wake times for each 24 hour period. Inconsistency scores for bed times and wake times were also created based on the sleep diary data, in which the variability of when the child went to sleep and woke up was given a score based on the greatest deviation in time, using 30 minute increments. For instance, if the child went to bed every night within a range of 30 minutes (e.g., 9:00 PM to 9:30 PM) that child would receive a score of 0 for bedtime inconsistency. If, however, the child’s sleep time varied by 90 minutes (e.g., 9:00 PM to 10:30 PM) the child would receive a sleep time inconsistency score of 2.

Family Functioning

Parents completed the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS) (Matheny et al., 1995). A total of 15 items are summed to create a total score in which higher scores reflect greater family chaos. Participants completed items by indicating the level of agreement with each statement (6-point scale, 0–5). Sample items include “we almost always seem to be rushed” and “you can’t hear yourself think in our home”. For this sample, a coefficient alpha for total chaos was found acceptable at 0.82. The chaos measure has been used and validated with direct observations of home environments and with young children from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds (Dumas et al., 2005; Farbiash, Berger, Atzaba-Poria, & Auerbach, 2014; Matheny et al., 1995).

Child Emotional and Behavioral Functioning

Parents completed the Behavioral and Emotional Screening System (BESS), a measure of emotional and behavioral problems. Thirty items are based on 4 content areas (lack of adaptive skills, preschool problems, externalizing problems, and internalizing problems), combined to create a total score of maladaptive behavior. Validation of the BESS with a sample of preschool children (n=1400) supported a bifactor model (i.e., a single overall score) to interpret emotional and behavioral risk (DiStefano & Kamphaus, 2007). Age- and sex-normed T-scores are derived and classified as Normal (10–60), Elevated (61–70), or Extremely Elevated (>71).

Home Bedroom Media Assessment

Parents completed a home assessment of the presence of a television where the target child sleeps at night (including children co-sleeping with parents). This measure has been previously associated with higher preschooler weight status (Boles, Scharf, Filigno, Saelens, & Stark, 2013).

Analytic Strategy

Data were examined for distributional assumptions and non-normal data were transformed for parametric analyses. Data cleaning revealed that two CSHQ subscales (Night Wakings and Poor Sleep Duration) required transformation to normalize shape. Group comparison tests and chi-square analysis for demographic differences across weight status and televisions in bedrooms were conducted to identify covariates. Next, Pearson correlations between primary study variables were calculated. A multivariate analysis of variance was used to test for differences across sleep behaviors between children with and without a television in their bedroom. A multivariate multiple linear regression model was conducted to evaluate the predictive value of family chaos and child emotional and behavioral functioning on child sleep behaviors. Preliminary analyses showed family chaos and child functioning were significantly related and raised multicollinearity concerns for subsequent model testing, however multicollinearity tests were insignificant (Tabachnick, 2001).

Mediation models of child functioning on sleep behaviors through family functioning were tested using bootstrapping methods and the PROCESS SPSS MACRO (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Briefly, bootstrapping mediation involves repeatedly sampling from the available data set to estimate indirect effects from each sampled set. A sampling distribution is based off empirical approximations to create confidence intervals for the indirect effect. Given the potential for asymmetrical percentile bootstrap-based CIs, bias-corrected CIs (95%) were utilized based on 5000 replications (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The significance of indirect effects can be evaluated by the exclusion of “0” within estimated confidence intervals. Child sleep behaviors were entered as criterion variables; child functioning was the predictor variable, and family chaos was the proposed mediator. Effect sizes for significant indirect effects were calculated based on kappa-squared statistic, κ2, which is defined as the “proportion of the maximum possible indirect effect” (Preacher & Kelley, 2011, p. 106). κ2 is interpreted similarly to Cohen’s 1988 guidelines, .01, .09, and .25 for small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, 1988).

Child functioning was transformed from a continuous to a dichotomous, categorical variable, to test clinically meaningful T-scores (Normal and Elevated-Extremely Elevated) for differences on family chaos, sleep behavior problems, and child and parent weight status. Independent samples t-tests were conducted for differences across family chaos and weight. A multivariate analysis of variance was conducted using BESS scores as the independent variable with CSHQ scales, bedtime/wake time inconsistency, and parent reported sleep duration as sleep behavior dependent variables. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.22 and Mplus V.7.3.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Parent participants were primarily mothers (93%), who were on average 32 years old. The majority of participants self-identified as being Hispanic (65%), with the remaining sample identified as being African American. Nearly 72% of all parents were measured to be in the overweight (33.8%) or obese category (38%). A chi-square analysis showed no relationship between race/ethnicity and parent weight status, χ2 (3, N = 71) = 5.2, p = 0.15. Sixty percent of participating parents received a high school diploma or less for highest achieved education level and 93% reported an annual income of less than $30,000. On average, children were 4.7 years old, 47% female, and 70% healthy weight. There were no significant relationships among parent BMI, child weight and child sleep variables, including parent reported sleep duration and sleep problems from the CSHQ scales. Additionally, demographic variables, including parent and child age, race/ethnicity, sex of child, parent education, and annual income were not significantly related with study variables and not included as control variables for model analyses. Parent and child demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (parent-child dyad overall n=73)

| Mean ± SD / % | |

|---|---|

| Child | |

| Child age (years) | 4.7 ± 0.6 |

| Sex (female) | 47% |

| zBMI | 0.4 ± 1.1 |

| Healthy weight | 69.9% |

| Overweight | 15.1% |

| Obese | 15.1% |

| Parent | |

| Relationship to child (Mother) | 93% |

| Age | 31.9 ± 7.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanic (% Spanish only speaking) | 64% (49.3%) |

| non-Hispanic Black | 33% |

| Hispanic Black | 1% |

| Other | 1% |

| BMI | 29.6 ± 6.6 |

| Under weight | 1.4% |

| Healthy weight | 26.8% |

| Overweight | 33.8% |

| Obese | 38.0% |

| Education (highest completed) | |

| Less than HS diploma | 38% |

| HS diploma | 22% |

| Partial College | 37% |

| College Degree | 3% |

| Annual Family Income | |

| Less than $30K | 93% |

| Between $30K and less than $50K | 6% |

| Greater than or equal to $50K | 1% |

Correlation tests showed Chaos was significantly positively related to BESS scores (Table 2). Additionally, Chaos was positively related to the CSHQ Total Sleep Problems scale and subscales for Bedtime Resistance and Sleep Anxiety. BESS T-scores were positively related to the CSHQ Total Sleep Problems scale and subscales for Bedtime Resistance, Sleep Anxiety, and Night Wakings. Children reportedly obtained, on average, about 10.3 hrs of daily sleep (SD=0.9) though sleep duration from diaries was not significantly correlated with other study variables. Finally, both Chaos and BESS scores positively related to Wake Time Inconsistency scores. Differences in sleep behavior problems based on the presence of a TV in the child’s bedroom were tested by a single multivariate analysis of variance and showed no significant differences. The presence of a TV was not significantly associated with Chaos (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Correlations / Means ± SD for Primary Study Variables

| Mean±SD (%) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal BMI | 29.6 ± 6.6 | -- | ||||||||||||

| 2. Child zBMI | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 0.22 | -- | |||||||||||

| 3. BESS | 50.4±10.5 | 0.12 | −0.03 | -- | ||||||||||

| 4. Chaos | 2.4±0.7 | 0.20 | −0.04 | 0.61†† | -- | |||||||||

| 5. TV in Child’s Bedroom‡ | 65% | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.21 | −0.07 | -- | ||||||||

| 6. Total Sleep Problems | 50.7±7.7 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.45†† | 0.40† | 0.20 | -- | |||||||

| 7. Bedtime Resistance | 10.0±3.0 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.34† | 0.47† | 0.15 | 0.74†† | -- | ||||||

| 8. Poor Sleep Duration | 4.5±1.3 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.60†† | 0.36† | -- | |||||

| 9. Sleep Anxiety | 6.5±2.2 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.34† | 0.25* | 0.12 | 0.66†† | 0.69†† | 0.30** | -- | ||||

| 10. Night Wakings | 4.3±1.6 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.38† | 0.35† | 0.10 | 0.71†† | 0.45†† | 0.48†† | 0.35† | -- | |||

| 11. Sleep Duration‡‡ | 10.3±0.9 | 0.11 | −0.07 | −0.21 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.05 | -- | ||

| 12. Wake Inconsistency | 3.8±2.2 | 0.18 | −0.09 | 0.31* | 0.33** | −0.13 | 0.26* | 0.37† | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.31* | -- | |

| 13. Bedtime Inconsistency | 3.4±2.2 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.43†† | -- |

Note: BESS= Behavioral Emotional Screening System T-score;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.005;

p<.001;

Point bi-serial correlation coefficient;

Parent reported sleep duration (hours) from 7-day diary.

The categorical analysis of BESS T-scores showed significant differences for Chaos between Normal (M = 2.16, SD = 0.55, n=58) and Elevated-Extremely Elevated (M = 3.15, SD = 0.53, n=16); t(71) = −6.25, p<0.001 (95% CI: −1.30, −0.67). There were no significant differences for child zBMI and parent BMI. A statistically significant MANOVA effect for BESS and sleep behavior variables was obtained, Wilks’ λ = .70, F(7, 56) = 3.49, p < 0.005. The multivariate effect size was estimated at 0.30 (partial eta squared; η2), indicating that 30% of the variance in the canonically derived dependent variable was accounted for by clinically meaningful categories of child behavioral and emotional functioning. Specifically, children with at-risk BESS T-scores were significantly more likely to have higher scores for Total Sleep Problems, F(1) = 18.48, p < .001., η2 = 0.23; Bedtime Resistance F(1) = 10.51, p < .005., η2 = 0.14; Night Wakings, F(1) = 16.55, p < .001., η2 = 0.21; and Wake Time Inconsistency, F(1) = 6.42, p < .05., η2 = 0.09.

Regression Analyses

The multivariate multiple regression model showed significant relationships between Chaos, BESS, and child sleep behavior problems. Higher reported Chaos significantly associated with higher scores for the CSHQ, specifically Bedtime Resistance (p = 0.001). Higher BESS scores positively associated with higher CSHQ scores, including Total Sleep Problems (p = 0.01), and Sleep Anxiety (p = 0.03). Table 3 shows the complete results from regression tests.

Table 3.

Multivariate Multiple Regression Model Results Predicting Child Sleep Behavior Problems

| Criterion | Predictor | β (s.e.) | B (s.e.) | P value | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sleep Problems | BESS | 0.34 (0.12) | 0.26 (0.09) | 0.01* | 0.23*** |

| Chaos | 0.19 (0.13) | 2.31 (1.59) | 0.15 | ||

|

| |||||

| Bedtime Resistance | BESS | 0.10 (0.13) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.42 | 0.22** |

| Chaos | 0.40 (0.012) | 1.80 (0.58) | 0.001*** | ||

|

| |||||

| Sleep Anxiety | BESS | 0.30 (0.13) | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.03* | 0.12 |

| Chaos | 0.08 (0.14) | 0.25 (0.05) | 0.60 | ||

|

| |||||

| Poor Sleep Duration | BESS | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.001) | 0.88 | 0.04 |

| Chaos | 0.26 (0.38) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.69 | ||

|

| |||||

| Night Wakings | BESS | 0.25 (0.13) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.06 | 0.16* |

| Chaos | 0.19 (0.13) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.14 | ||

|

| |||||

| Sleep Duration (Diary) | BESS | −0.30 (0.15) | −0.02 (0.01) | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Chaos | 0.18 (0.16) | 0.23 (0.21) | 0.27 | ||

|

| |||||

| Bedtime Inconsistency | BESS | 0.14 (0.15) | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.34 | 0.14 |

| Chaos | 0.27 (0.15) | 0.88 (0.50) | 0.08 | ||

|

| |||||

| Sleep time Inconsistency | BESS | 0.06 (0.16) | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.69 | 0.02 |

| Chaos | 0.09 (0.17) | 0.30 (0.54) | 0.58 | ||

Note: BESS= Behavioral Emotional Screening System.

P≤.05;

P≤.01;

P≤.005

Mediation Analyses

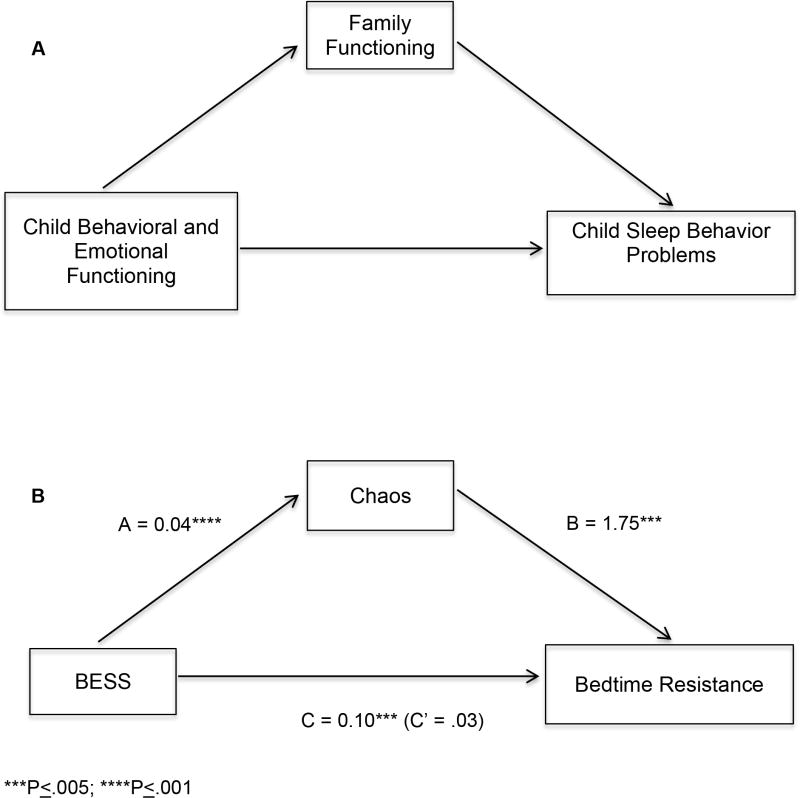

Two sleep behavior problem outcome variables were significantly associated with Chaos or BESS T-scores, explaining a significant amount of model variance: (1) Total Sleep Problems (R2 = 0.23) and (2) Bedtime Resistance (R2 = 0.22). Based on our hypothesized conceptual model in which child functioning would explain sleep behavior problems through family functioning (Figure 1, A), bootstrap mediation models were conducted with Chaos as the mediator between BESS and each sleep behavior problem. As depicted in Figure 1(B), Chaos significantly fully mediated the relationships between BESS and Bedtime Resistance (p = 0.028). The effect size for the indirect effect of Chaos on Bedtime Resistance (κ2) = 0.20 and in the range of Medium effects. The mediation test of the indirect effect of Chaos on BESS and Total Sleep problems was not significant (delta > .05).

Figure 1.

Family chaos as a mediator of child functioning on child sleep problem behaviors. (A) Depicts conceptual basis for mediation models; (B) displays outcomes for Child BESS mediation. BESS = Behavioral Emotional Screening System. C = Total effect of BESS on Bedtime Resistance; C’ = Direct effect of BESS on Bedtime Resistance, independent of Chaos.

Discussion

The results from this study showed that both child and family level factors were independent risk factors for child sleep behavior problems in children at risk for obesity. Our results, supporting our primary hypotheses, showed that higher family chaos and higher scores for child emotional and behavioral problems significantly predicted higher parent reported scores for bedtime resistance, sleep anxiety, and total sleep problems. The largest significant effects, however, were found between family and child functioning and bedtime resistance and total sleep problems. Indirect testing showed that children with higher scores for emotional and behavior problems were more likely to have higher bedtime resistance, but higher levels of chaos can account for this relationship. Longitudinal and experimental investigations that reduce family chaos need to be conducted to further evaluate and replicate this finding.

The present study showed no relationship between measured child weight and sleep duration based on sleep diaries or with general questions regarding poor sleep duration. This is in contrast to multiple studies, which have showed significant associations between preschool weight status and sleep duration (Cappuccio et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2008). Objective measurements of sleep for very-low income preschool children from minority backgrounds remain limited and require additional research to clarify the relation of family chaos and potential socioeconomic differences for sleep duration and risk for higher weight status (Chen et al., 2008). In addition to possible measurement issues, no associations between sleep behavior problems and weight status may have also been a function of our timeline. That is, associations among health behaviors are often easier to detect compared to differences or changes to BMI due to the possibility of a lag effect of behavior and health outcomes. Thus, future research designs that include longitudinal and experimental approaches may better clarify the relationship between sleep behavior problems and weight status during early childhood. Despite the absence of a relationship between poor sleep and weight status in our sample, multiple consequences from poor sleep remain important to consider in addition to weight status, such as increased risk for externalizing and internalizing problems, reduced memory and attention, and other emotional problems during childhood (Holley, Hill, Stevenson, 2011; Goodlin-Jones, 2009; Hatzinger 2010).

Conceptually, short sleep duration may be a function of a child who is resistant to entering bed and going to sleep. Child resistance behaviors to going to bed are common; yet, few investigations have linked bedtime resistance behaviors to sleep duration (Lozoff et al., 1985). Our results suggest that improving family functioning to be less “chaotic” and child emotional and behavioral problems may significantly reduce bedtime resistance behaviors.

Practically speaking, less chaotic families should be more organized, routine based, and with greater structure regarding daily activities, which may support health outcomes. Studies on family routines support this conceptualization and have shown that families of preschool-aged children reporting mealtime routines, consistent sleep, and consistent limits on screen time were about 40% lower in obesity prevalence compared to families not reporting any of these routines (Anderson & Whitaker, 2010). Moreover, families identified as being Hispanic and African American, compared to white children, were significantly less likely to report early bedtimes and a bedtime routine (Hale, Berger, LeBourgeois, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). Lower use of bedtime routines has also been associated with low maternal education, larger household size, and poverty status (Hale et al., 2009). Collectively, the differences in reported routines by race and ethnicity indicate that family chaos may be culturally and socioeconomically based, though additional studies are needed to clarify these relationships. Such future studies are further needed, given the fact that racial/ethnic differences in BMI may be better explained by social, lifestyle, and physical environmental factors distinctly different from SES (Wang & Beydoun, 2007). While it may appear that family chaos could reflect poor parenting behaviors, high family chaos has been shown to significantly predict greater child behavior problems over and above parenting behaviors, child age, and sex of child (Coldwell, Pike, & Dunn, 2006). Interventions that evaluate the multiple components of family chaos are needed to identify the specific components that drive the relationship between chaos and child functioning, particularly in relation to child behaviors that predict higher weight status.

Our results did not show support for an association between child weight status and the presence of televisions in their bedrooms. This is in contrast to our own prior study and from others who examined preschool children, bedroom media and weight, in which children who overweight or obese were more likely to have a TV in the bedroom (Boles et al., 2013; Dennison, Erb, & Jenkins, 2002). Our present data, however, includes only low-income minority children, in which the healthy weight children showed substantially higher availability of a TV in their bedroom (64%) compared to middle income, white preschool, healthy weight children of our prior study (12.8%) (Boles et al., 2013). Therefore, associations between weight and the availability of bedroom TVs may be associated with other socioeconomic and cultural factors, as noted in recent research finding ethnic-specific differences in the availability of TVs among low-income, minority preschool children (Chuang, Sharma, Skala, & Evans, 2013).

The contributions of this study should be considered with potential limitations. This study included a relatively small sample of Hispanic and African American families from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and the results may not generalize to other families with different demographic characteristics. Replications with larger, similar demographic samples are needed to assess the durability of the present findings. Family chaos and child functioning were also significantly statistically related and may have created multicollinearity concerns during model testing, although multicollinearity tests were insignificant (Tabachnick, 2001). Further, our study did not evaluate for the use of portable screens, such as tablets or smart phones which have been associated with sleep difficulties and duration (Lemola, Perkinson-Gloor, Brand, Dewald-Kaufmann, & Grob, 2015). Additional environmental assessments will need to consider mobile devices given the change in availability of these technologies. Lastly, the mediation tests were conducted using models that assume temporal order of effects which require longitudinal and experimental confirmation to assess causality (Kline, 2011). An alternative model was tested in which family chaos predicting child sleep problems would be mediated by child emotional and behavioral functioning. However, mediation analyses failed to show support for this competing model (results not shown).

These results identify the importance of family and preschool child functioning in relation to specific child sleep behavior problems that may impact other child outcomes not related to short sleep duration and weight status. This study extends the literature by determining the direct and indirect effects of child and family functioning on sleep problems, showing that children from families with high levels of chaos are significantly more likely to show bedtime resistance; accounting for the effect that poor child functioning may have on bedtime resistance. Moreover, our results found no relationship between sleep issues and child weight status, which raises the possibility that sleep duration and sleep environments may actually be indicators for family chaos, a potential causal factor related to childhood obesity. Our results provide potentially important focal points of intervention related to poor sleep and obesity for low-resource families of young children with minority status. Future research aimed at improving child sleep routines and earlier bedtimes for increased sleep duration may benefit from family level targets, including family chaos, particularly when children exhibit emotional and behavior problems.

Table 4.

Mediation Models for Child Functioning Predicting Sleep Problems via Family Chaos

| Dependent Variable | Model R2 | Total effect coefficient (S.E.) | Bias corrected indirect effect confidence interval (95%) | Direct effect coefficient (S.E.) | Delta (Z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sleep Problems | 0.23 | 0.35 (0.08)**** | (−0.02, 0.21) | 0.26 (0.10)** | 1.40 |

| Bedtime Resistance | 0.22 | 0.10 (0.03)*** | (0.03, 0.13) | 0.03 (0.04) | 2.65** |

Note: BESS= Behavioral Emotional Screening System.

P<.01;

P≤.005;

P≤.001

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, through a career development award from The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (K23-DK087826) supporting the first author, R.E.B.

Contributor Information

Richard E. Boles, University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus

Ann C. Halbower, University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus

Stephen Daniels, University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus.

Thrudur Gunnarsdottir, Washington University.

Nancy Whitesell, University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus.

Susan L. Johnson, University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus

References

- Anderson SE, Whitaker RC. Household routines and obesity in US preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):420–428. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelhans BM, Fitzpatrick SL, Li H, Cail V, Waring ME, Schneider KL, Pagoto SL. The home environment and childhood obesity in low-income households: indirect effects via sleep duration and screen time. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajoghli H, Alipouri A, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Brand S. Sleep patterns and psychological functioning in families in northeastern Iran; evidence for similarities between adolescent children and their parents. J Adolesc. 2013;36(6):1103–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles RE, Scharf C, Filigno SS, Saelens BE, Stark LJ. Differences in home food and activity environments between obese and healthy weight families of preschool children. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(3):222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the Family as a Context for Human-Development - Research Perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22(6):723–742. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.22.6.723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byars KC, Yolton K, Rausch J, Lanphear B, Beebe DW. Prevalence, patterns, and persistence of sleep problems in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e276–284. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, Currie A, Peile E, Stranges S, Miller MA. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep. 2008;31(5):619–626. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Beydoun MA, Wang Y. Is sleep duration associated with childhood obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(2):265–274. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis DA, Ebel BE, Rivara FP, Zimmerman FJ. Television, video, and computer game usage in children under 11 years of age. J Pediatr. 2004;145(5):652–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang RJ, Sharma S, Skala K, Evans A. Ethnic differences in the home environment and physical activity behaviors among low-income, minority preschoolers in Texas. Am J Health Promot. 2013;27(4):270–278. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110427-QUAN-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell J, Pike A, Dunn J. Household chaos--links with parenting and child behaviour. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(11):1116–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, El-Sheikh M. Considering sleep in a family context: introduction to the special issue. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(1):1–3. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison BA, Erb TA, Jenkins PL. Television viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk among low-income preschool children. Pediatrics. 2002;109(6):1028–1035. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano CA, Kamphaus RW. Development and validation of a behavioral screener for preschool-age children. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2007;15(2):93–102. doi: 10.1177/10634266070150020401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Nissley J, Nordstrom A, Smith EP, Prinz RJ, Levine DW. Home chaos: sociodemographic, parenting, interactional, and child correlates. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(1):93–104. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt JA, Mize J, Acebo C. Marital conflict and disruption of children’s sleep. Child Dev. 2006;77(1):31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Gonnella C, Marcynyszyn LA, Gentile L, Salpekar N. The Role of Chaos in Poverty and Children’s Socioemotional Adjustment. Psychological Science. 2005;16(7):560–565. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01575.x16008790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farbiash T, Berger A, Atzaba-Poria N, Auerbach JG. Prediction of preschool aggression from DRD4 risk, parental ADHD symptoms, and home chaos. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42(3):489–499. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9791-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines J, McDonald J, O’Brien A, Sherry B, Bottino CJ, Schmidt ME, Taveras EM. Healthy Habits, Happy Homes: randomized trial to improve household routines for obesity prevention among preschool-aged children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1072–1079. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L, Berger LM, LeBourgeois MK, Brooks-Gunn J. Social and demographic predictors of preschoolers’ bedtime routines. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(5):394–402. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181ba0e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L, Berger LM, LeBourgeois MK, Brooks-Gunn J. A longitudinal study of preschoolers’ language-based bedtime routines, sleep duration, and well-being. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25(3):423–433. doi: 10.1037/a0023564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrin DC, McGrath JJ, Drake CL. Beyond sleep duration: distinct sleep dimensions are associated with obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37(4):552–558. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, Johnson CL. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Arend R, Rosenbaum D, Smith A, Weissbluth M, Binns HJ, Christoffel KK. Sleep and behavior problems among preschoolers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20(3):164–169. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199906000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemola S, Perkinson-Gloor N, Brand S, Dewald-Kaufmann JF, Grob A. Adolescents’ electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(2):405–418. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozoff B, Wolf AW, Davis NS. Sleep problems seen in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1985;75(3):477–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee CA, Gordon R, Caputi P. Distinct developmental trends in sleep duration during early childhood. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1561–1567. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny AP, Wachs TD, Ludwig JL, Phillips K. Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. Jul-Sep 1995. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1995;16(3):429–444. doi: 10.1016/0193-3973%2895%2990028-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- May AL, Pan LP, Sherry B, Blanck HM, Galuska D, Dalenius K, Grummer-Strawn LM. Vital Signs: Obesity Among Low-Income, Preschool-Aged Children - United States, 2008–2011. Mmwr-Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(31):629–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Relationship between child sleep disturbances and maternal sleep, mood, and parenting stress: a pilot study. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(1):67–73. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, Boehlecke B, Brown TM, Coleman J, Jr American Academy of Sleep, M. Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1277–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Parisi SM. Sedentary behavior and sleep: paradoxical effects in association with childhood obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33(Suppl 1):S82–86. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA, Jones C. Parental knowledge of healthy sleep in young children: results of a primary care clinic survey. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32(6):447–453. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31821bd20b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. 2000;23(8):1043–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(2):93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf RJ, Demmer RT, Silver EJ, Stein RE. Nighttime sleep duration and externalizing behaviors of preschool children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34(6):384–391. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31829a7a0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon P, Peacock GG, Crowley SL. Assessment of sleep problems in preschool aged children: an adaptation of the children’s sleep habits questionnaire. Behav Sleep Med. 2013;11(4):283–296. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.707158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1(3):e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchette E, Petit D, Seguin JR, Boivin M, Tremblay RE, Montplaisir JY. Associations between sleep duration patterns and behavioral/cognitive functioning at school entry. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1213–1219. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bulck J. Television viewing, computer game playing, and Internet use and self-reported time to bed and time out of bed in secondary-school children. Sleep. 2004;27(1):101–104. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang Q. Are American children and adolescents of low socioeconomic status at increased risk of obesity? Changes in the association between overweight and family income between 1971 and 2002. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(4):707–716. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H, Molinari L, Guyer C, Jenni OG. Agreement rates between actigraphy, diary, and questionnaire for children’s sleep patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(4):350–358. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KE, Lumeng JC, Kaciroti N, Chen SY, LeBourgeois MK, Chervin RD, Miller AL. Sleep Hygiene Practices and Bedtime Resistance in Low-Income Preschoolers: Does Temperament Matter? Behav Sleep Med. 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2014.940104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KE, Miller AL, Bonuck K, Lumeng JC, Chervin RD. Evaluation of a sleep education program for low-income preschool children and their families. Sleep. 2014;37(6):1117–1125. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]