Abstract

Objectives

Most individuals with dementia develop significant behavioral problems. Restlessness is a behavioral symptom frequently endorsed by caregivers as distressing, yet is variably defined and measured. Lack of conceptual and operational clarity hinders an understanding of this common behavioral type, its prevalence, and development of effective interventions. We advance a systematic definition and understanding of restlessness from which to enhance reporting and intervention development.

Method

We reviewed the literature for existing definitions and measures of restlessness, identified common elements across existing definitions, assessed fit with relevant theoretical frameworks, and explored the relationship between restlessness and other behavioral symptoms in a data set of 272 community-dwelling persons with dementia.

Results

Twenty-five scales assessing restlessness were identified. Shared components included motor/neurological, psychiatric, and needs-based features. Exploratory analyses suggest that restlessness may co-occur primarily with argumentation, anxiety, waking the caregiver, delusions/ hallucinations, and wandering. We propose that restlessness consists of three key attributes: diffuse motor activity or motion subject to limited control, non-productive or disorganized behavior, and subjective distress. Restlessness should be differentiated from and not confused with wandering or elopement, pharmacological side effects, a (non-dementia) mental or movement disorder, or behaviors occurring in the context of a delirium or at end-of-life.

Conclusion

Restlessness appears to denote a distinct set of behaviors that have overlapping but non-equivalent features with other behavioral symptoms. We propose that it reflects a complex behavior involving three key characteristics. Understanding its specific manifestations and which components are present can enhance tailoring interventions to specific contexts of this multicomponent behavioral type.

Keywords: Restlessness, behavioral symptoms, dementia, neurocognitive disorder, definition

Introduction

Dementia is an increasingly prevalent disease that is projected to affect approximately 14 million Americans aged 65 years and older by 2050 – a number that is nearly triple the 5.1 million older Americans currently affected in 2015 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2015). Worldwide, this disease affects 47.5 million persons, is a major contributor to disability and dependency, and is one of the leading causes of death (World Health Organization, 2015). Also referred to as major neurocognitive disorder in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), dementia is typically accompanied by behavioral disturbances that occur across the disease trajectory but often worsen or increase in frequency with disease progression. Nearly all people with dementia will develop significant behavioral problems at some point in the course of illness (Lyketsos et al., 2002; Profenno, Tariot, & Ismail, 2005). Behavioral symptoms, also referred to as neuropsychiatric symptoms, neurobehavioral symptoms, or behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, encompass a wide range of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms that may be due to a combination of biological changes in the brain, biological stressors (e.g., medical illness), heightened vulnerabilities to an individual’s relationships and interactions with their physical and social environment, unmet needs, and a deterioration of effective coping mechanisms (Hyman, 2006; Kales, Gitlin, & Lyketsos, 2015; Mitty & Flores, 2007; Tampi et al., 2011).

Behavioral symptoms and the increased need for more comprehensive and complex levels of care related to the progression of dementia pose significant challenges to caregivers, and are common reasons for long-term care placement (de Vugt et al., 2005). Furthermore, behavioral symptoms are cited as the most distressing aspects of providing care for persons with dementia and account for greater health care utilization and costs, including increased hospitalizations and nursing home placement (Murman et al., 2002).

There is a growing awareness of the importance of preventing, assessing, monitoring, and managing behavioral symptoms in dementia care, as this can assist in identifying and addressing potential unmet needs (Gaugler, Kane, Kane, & Newcomer, 2005; Odenheimer et al., 2013), and help lead to a differential diagnosis (Kertesz, Nadkarni, Davidson, & Thomas, 2000). Research also suggests that managing behaviors may slow the disease progression (Peters et al., 2015). The first step in managing behavioral symptoms is detecting their occurrences (Gitlin, Kales, & Lyketsos, 2012), and a number of instruments have been developed to assess and measure psychopathology and behavioral symptoms in dementia (Gitlin, Marx, Stanley, Hansen, & Van Haitsma, 2014). These assessments tend to categorize behavioral symptoms within five primary clusters: depression, agitation, aggression, apathy, and psychosis (McShane, 2000), although other behavioral symptoms are common and identified by caregivers as problematic including restlessness (Gitlin, Winter, Dennis, & Hauck, 2007).

Given that behavioral symptoms are almost universal in persons with dementia and occur across disease type and stage, understanding their phenotype, prevalence, and measurement is critical in order to advance an effective and comprehensive approach to care. One common behavior that caregivers cite as problematic, yet appears to lack definitional clarity and consistency in the literature, is restlessness. There are varied categorizations and definitions of restlessness in persons with dementia, which has resulted in an inconsistent reporting of and variation in prevalence rates across studies. Rates appear to range from 21% (D’Onofrio et al., 2012) to 44% (Zuidema, Derksen, Verhey, & Koopmans, 2007), depending upon the populations studied (including etiology and demographic characteristics) and assessment scales and definitions used to assess restlessness. For example, the rate of restlessness reported in D’Onofrio et al. (2012) is based on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI; Cummings et al., 1994), which captures restless-type behaviors under the heading of aberrant motor behavior, defined as: ‘Does the patient pace, do things over and over such as opening closets or drawers, or repeatedly pick at things or wind string or threads?’ The rate of restlessness in Zuidema et al. (2007) is based on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI; Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, & Rosenthal, 1989), which defines general restlessness as ‘fidgeting, always moving around in seat, getting up and sitting down inability to sit still.’ It should also be noted that these prevalence rates are based on very different sample populations (i.e., Alzheimer’s Evaluation Unit, D’Onofrio et al., 2012 vs. skilled nursing facility, Zuidema et al., 2007) and, while sampling differences may contribute to the varied rates of restlessness, it is also likely that the different definitions in the measures used led to disparities in prevalence rates across studies.

Thus, although restlessness appears to occur frequently and be upsetting to families, prevalence rates are inconsistent due primarily to the inadequacies in conceptualization and measurement. This has also hindered intervention development for this behavioral disturbance and promoted ineffective and variable treatment practices, including misprescription of medications to sedate or calm an older adult viewed as agitated (Tija, 2014; Tija et al., 2010). It is unclear to what degree persons with dementia are aware of restless behavior; however, the literature suggests an increase in other behavioral symptoms and behaviors in general across dementia subtypes as anosognosia increases (Aalten, van Valen, Clare, Kenny, & Verhey, 2005; Banks & Weintraub, 2008; de Carolis et al., 2015; Harwood, Sultzer, & Wheatley, 2000).

The ambiguity in the conceptual and operational definition of restlessness was recognized over 20 years ago (e.g., Kolanowski, 1991; Sachdev & Kruk, 1996). However, limited progress has been made towards ensuring the operationalization of this behavioral type. The purpose of this paper is to advance a definition of restless-type behaviors and provide recommendations for future directions in research, measurement, and intervention development in this area. Differentiating and delineating the characteristics of specific behavioral types can lead to advancing targeted interventions and boost effectiveness.

To derive an understanding of this construct, we used three approaches: we reviewed definitions and the scientific literature and relevant scales; we examined pertinent theoretical frameworks; and we conducted an exploratory analysis of the relationships between restlessness and other behavioral symptoms of dementia using the baseline data from two separate trials testing a nonpharmacological approach to behavioral management. Through these sources, we considered the common or shared core features of restlessness, and how this behavior can be differentiated from other behaviors. For example, wandering, agitation, aggression, and anxiety have all been associated with restless behaviors in various measurement tools, although it is unclear whether or not these behaviors are forms of restlessness. Distinguishing between what restlessness is and what it is not is important, as this sets boundaries to the construct from which to clearly operationalize its measurement and derive interventions.

Methods

To derive a definition of dementia-related restlessness, we implemented inductive (i.e., analysis of existing definitions, studies, and scales to identify commonalities), deductive (i.e., identifying major theoretical frameworks of behavioral symptoms of dementia and describing how each theory conceptualizes restlessness), and inferential analytical (i.e., exploratory data analysis) approaches. Discussed below, these exploratory analyses were conducted in order to help distinguish restlessness from other behavioral symptoms as well as to identify components of restlessness based on the strength of its relationships with other behaviors.

As previously mentioned, we first examined three sources: vernacular definitions, definitions offered in scientific articles, and definitions offered in scales that included restlessness. The vernacular usages of restlessness were assessed through consultation of four dictionary sources, which were selected based on reputation for being a definitive source or were used in prior research to define other dementia-related behaviors (Algase, Moore, Vandeweerd, & Gavin-Dreschnack, 2007). Second, to identify definitions of restlessness in the literature, we examined relevant theoretical models based on previously published works conceptualizing behavioral symptoms of dementia (e.g., Cohen-Mansfield, 2000; Ishii, Streim, & Saliba, 2012).

To examine the use of the term in scales and scientific articles, we conducted a systematic literature review over the past 45 years for pertinent measurement tools, behavioral scales, and conceptual papers related to dementia behaviors. A comprehensive computerized search of peer-reviewed published studies (1 January 1970–10 October 2014) was conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO, Medline, CINAHL Plus, CINAHL, Google Scholar, Ovid, and EBSCO using the following search terms: restless, restlessness, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, behavior, psychomotor, agitation, aberrant motor behavior, motor disturbance, pacing, wandering, akathisia, anxiety, aggression, behavioral symptoms, definition, behavioral assessment, cognitive assessment, rating scale, neuropsychological measurements, and sleep. Additionally, a search of book chapters, review papers, and meta-analyses of neuropsychological measures was completed and the reference sections were cross-checked with the original search. Papers identified through this process were further searched for additional references related to relevant assessment scales or studies. Studies and scales were selected with the following criteria: (1) published or available in English; (2) presented or utilized a behavioral scale or definition that either directly addressed restlessness or similar behavioral symptoms, (3) were developed for or tested in persons with dementia, and (4) one or more psychometric properties were reported.

Finally, to derive a definition, we also examined the relationship of restlessness to other behavioral symptoms to help distinguish its features. To this end, we combined and analyzed data from two randomized controlled trials: (1) Project ACT (Gitlin et al., 2007), which tested the effectiveness of a nonpharmacological home-based intervention to reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and caregiver distress, and (2) Project COPE (Gitlin, Winter, Dennis, Hodgson, & Hauck, 2010), a nonpharmacological, biobehavioral approach to support daily function and quality of life for patients with dementia and the well-being of their caregivers. In both trials, caregivers completed the Agitated Behavior in Dementia Scale (ABID; Logsdon et al., 1999) at baseline (prior to randomization and receipt of interventions). For these analyses, we examined the caregiver-rated frequency (over the preceding two weeks) of 16 different behaviors exhibited by the person with dementia on a scale of zero to three (0 = did not occur; 3 = occurred daily or more often).

Results

Existing measures and definitions

Vernacular definitions

We also examined the use of restlessness in everyday vernacular (Algase, Moore, et al., 2007). Across dictionary sources, the features and behaviors included in definitions of restlessness were: (1) inability to relax or settle, uneasiness, agitation; (2) constant motor activity or motion; (3) unhappiness, discontent, boredom; and (4) sleeplessness (Concise Oxford Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary, MacMillan Dictionary, Roget’s Thesaurus).

Prevailing definitions

We next consulted the scientific literature related to dementia behaviors to identify previous scientific definitions of restlessness. One of the first published definitions of restlessness proposed in 1975 defined this construct as ‘a discontinuous animal behavior evidenced by non-specific, repetitive, unorganized, diffuse, apparently non-purposeful motor activity that is subjected to limited control’ (Norris, 1975, p. 107).

In 1991, Kolanowski derived two common attributes of restlessness in older adults from the literature: (1) diffuse motor activity prompted by or in response to arousing or challenging changes, and (2) actual perception of these changes as either arousing or challenging. Kolanowski’s (1991) definition is based on Activation Theory (Hebb, 1955; Kroeber-Riel, 1979; Lindsley, 1951), which holds that the level of activation is a function of cortical stimulation of the reticular activating system, which in turn stimulates other areas of the brain and leads to increased arousal, psychological and motor activity, and information processing. However, neither Kolanowski’s (1991) definition nor its conceptual basis account for the effects of dementia on cognition (e.g., information processing), brain function, and communication of brain networks, which can alter arousal thresholds and stimulus interpretation.

In 1996, Sachdev and Kruk (1996) proposed a slightly different definition: (1) excessive and/or inappropriate motor activity, which is recognized as being voluntary and can at least be partially suppressed for varying periods of time; (2) the activity is repetitious and nonproductive, and either leads to difficulties for the individual, or to those immediately around him/her, or to his/her carers, or is judged to be socially inacceptable; and (3) there is an associated mental or subjective distress, either reported by the individual or inferred from the behavior. Sachdev and Kruk (1996) further described additional features that may be present: excessive or inappropriate verbal activity, aggressive or violent behavior, and/or self-manipulating or self-harming behaviors.

Sachdev and Kruk’s (1996) definition was a significant step towards defining restlessness as a neuropsychiatric symptom, and common etiologies of restless behaviors such as nonorganic mental disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, attentional disorders) and organic disorders (e.g., drug-induced restlessness) were presented. However, their definition was not specific to its presentation in dementia, and also did not clearly distinguish between restless behaviors and other behaviors that have been identified as distinct in recent studies (e.g., Algase et al., 2008).

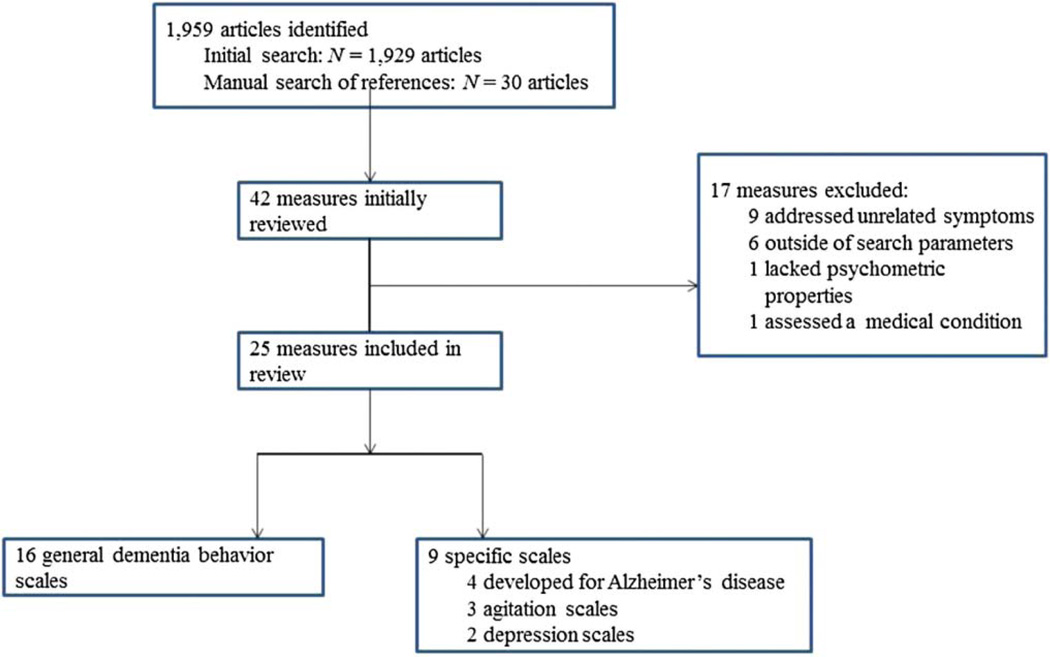

Scale review

The initial search yielded 1929 papers (Figure 1). Through manual searches of these papers, an additional 30 were identified. Among these 1959 papers, 41 measures were identified, of which 25 (58.5%) met inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Measures developed for other populations were included if there was evidence in the literature of use with persons with dementia. Of the 17 measures not included in the review, nine (52.9%) were excluded because they did not address restlessness or related behavioral symptoms, one (5.9%) did not report psychometric properties, and one (5.9%) was developed for measurement of symptoms specifically associated with a medical condition. Additionally, despite placing limits on the search, six (35.3%) measures were initially identified but upon further inspection were determined to be outside of our search parameters (e.g., published before 1970). Modified versions of scales already included for review (e.g., shortened versions) were excluded.

Figure 1.

Search flowchart.

Of the 25 scales included in this review, 17 (68%) specifically used some variation of the term ‘restlessness.’ Eight (32%) scales did not use the term ‘restlessness’ directly but included behaviors relevant to this term or which described this behavior by related terms including ‘activity disturbances,’ ‘repetitive activity,’ ‘purposeless activity,’ ‘pacing’ or ‘wandering,’ increased motor activity, motor agitation, aberrant motor behavior, fidgeting, agitation, and getting up at night. A motor component was the only common element across scales and studies, and nearly all of the scales (N = 24; 96%) indicated that there was a motor component to the restless behavior. Ten of the scales (40%) specifically noted that restless behavior lacked intention or was without purpose. Thirty-six percent of the scales distinguished between restlessness at night/while in bed and other forms of restlessness that occur during the day.

An understanding of restlessness must not only include what it is, but also how it is distinct from other behaviors, or what it is not. For example, wandering, agitation, aggression, and anxiety have each been associated with restless behaviors depending on the measurement tool being used. Factor analysis of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia (CERAD-BRSD; Tariot et al., 1995) found that restlessness, verbal and physical aggression, attempts to leave residence, and physical signs of anxiety comprised the same factor based on the definitions of those constructs in the scale. Restlessness, aggression, agitation, and wandering are essentially presented as a unified construct under the heading of agitation on the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale (Sultzer, Levin, Mahler, High, & Cummings, 1992). Factor analyses of several scales have noted that restless behaviors load with other motoric behaviors (e.g., Rabinowitz et al., 2005).

Towards a unified definition of restlessness

Conceptual models

We have identified four theoretical models that may have applicability to restlessness and which have been used previously to understand other behavioral symptoms and inform intervention development: (1) neurobiological/genetic framework (e.g., Cohen-Mansfield, 2000; Garand & Hall, 2000; Raskind & Peskind, 1994), (2) behavioral model (e.g., Teri, 1997), (3) reduced stress threshold model (Hall & Buckwalter, 1987; Smith, Gerdner, Hall, & Buckwalter, 2004), and (4) unmet needs model (e.g., Algase et al., 1996).

Neurobiological/genetic model

The neurobiological/genetic model postulates that behavioral symptoms are the result of changes in the brain that are associated with dementia (Cohen-Mansfield, 2000; Garand & Hall, 2000; Raskind & Peskind, 1994). However, not all restless-type behaviors appear to be attributable to neurobiological causes. For example, a motoric component is common to all restless behaviors (Table 1), and many of the motor symptoms that result from brain changes such as neurotransmitter dysfunction are Parkinsonian in nature. However, restlessness has been distinguished from tremors or other movement disorders (Plumb & Bain, 2007), and it is therefore unlikely that a neurologically driven component can fully explain or be specific to restlessness. The neurobiological/genetic model may, however, account for some nighttime restlessness, as the sleep-wake cycle is severely disrupted due to brain changes that occur in dementia. Further research is needed to elucidate the relationship between restless-type behaviors and neurological mechanisms. Regarding genetic contributions to behavioral symptoms, research suggests that familial Alzheimer’s disease (AD) – also known as early-onset AD – is associated with more pronounced behavioral symptoms than the more common late-onset AD (Garand & Hall, 2000).

Table 1.

Summary of instruments that address restlessness and their specific components.

| Scale name | Overall label | Restlessness mentioned specifically |

Lacks intention |

Motor component |

Associated with night disturbances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBS (Gottfries, Bråne, Gullberg, & Steen, 1986) | Restlessness | X | X | X | |

| BEHAVE-AD (Reisberg et al., 1987) | Activity disturbance | X | X | ||

| ADAS (Rosen, Mohs, & Davis, 1984) | Noncognitive behavior | N/S | X | ||

| CSDD (Alexopoulos, Abrams, Young, & Shamoian, 1988) | Agitation | X | N/S | X | X |

| DMAS (Sunderland et al., 1988) | Physical agitation; Sleep | X | X | X | X |

| CMAI (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 1989) | General restlessness | X | N/S | X | |

| DBRS (Mungas, Weiler, Franzi, & Henry, 1989) | Agitation | X | N/S | X | |

| DBD (Baumgarten, Becker, & Gauthier, 1990) | Limb movements | X | X | X | |

| NOSGER (Spiegel, Brunner, & Ermini-Fünfschilling, 1991) | Restless at night | X | N/S | X | X |

| BEAM-D (Sinha et al., 1992) | Anxiety; Sleep | X | N/S | X | |

| BSSD (Devanand, Brockington, et al., 1992) | Disinhibition | X | X | ||

| COBRA (Drachman, Swearer, O’Donnell, Mitchell, & Maloon, 1992) | Mechanical/Motor | X | X | X | |

| CRBRS (Lefroy, Hobbs, & Hyndman, 1992) | Restlessness | X | N/S | X | |

| CUSPAD (Devanand, Brockington, et al., 1992) | Behavioral disturbances | X | N/S | X | X |

| NHBPS (Ray, Taylor, Lichtenstein, & Meador, 1992) | Fidgets; Unable to sit still; Restless | X | X | X | |

| NRS (Sultzer et al., 1992) | Agitation; Excessive motor activity | X | N/S | X | |

| NPI (Cummings et al., 1994) | Aberrant motor behavior | X | X | X | |

| DSS (Loreck, Bylsma, & Folstein, 1994) | Overactive behaviors | X | N/S | X | |

| PAS (Rosen et al., 1994) | Motor agitation | X | X | ||

| CERAD-BRSD (Tariot et al., 1995) | Defective self-regulation | X | N/S | X | |

| DBRI (Molloy, Bédard, Guyatt, & Lever, 1996) | Agitation | N/S | X | X | |

| MOUSEPAD (Allen, Gordon, Hope, & Burns, 1996) | Walking behaviors | N/S | X | X | |

| CDBQ (Victoroff, Nielson, & Mungas, 1997) | Agitation | X | X | X | |

| ABID (Logsdon et al., 1999) | Restlessness | X | N/S | X | |

| KSBA (Hopkins, Kilik, Day, Bradford, & Rows, 2006) | Motor restlessness | X | X |

Note: ABID D Agitated Behavior in Dementia Scale; ADAS D Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale; BEAM-D D Behavioral and Emotional Activities Manifested in Dementia; BEHAVE-AD D Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale; BSSD D Behavioral Syndromes Scale for Dementia; CDBQ D California Dementia Behavior Questionnaire; CERAD-BRSD D Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia; CMAI D Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory; COBRA D Caregiver Obstreperous Behavior Rating Assessment; CRBRS D Crichton Royal Behavior Scale; CSDD D Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; CUSPAD D Columbia University Scale for Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease; DBD D Dementia Behavior Disturbance Scale; DBRI D Dysfunctional Behaviour Rating Instrument; DBRS D Disruptive Behavior Rating Scales; DMAS D Dementia Mood Assessment Scale; DSS D Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale; GBS D Gottfries–Bråne-Steen Scale; KSBA D Kingston Standardized Behavioral Assessment; MOUSEPAD D Manchester and Oxford Universities Scale for the Psychopathological Assessment of Dementia; NHBPS D Nursing Home Behavior Problem Scale; NOSGER D Nurses’ Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients; NPI D Neuropsychiatric Inventory; NRS D Neurobehavioral Rating Scale; PAS D Pittsburgh Agitation Scale; N/S D not specified.

Behavioral model

According to the behavioral model, also known as the ‘ABC model,’ behavioral symptoms are controlled by their antecedents and consequences. As such, the consequences of behaviors serve as positive or negative reinforcers of the relationships between antecedents and behaviors, and removing the antecedents could theoretically prevent the behaviors (Teri, 1997). The behavioral model does not account for the findings that restless-type behaviors are generally non-productive or disorganized, and fail to address potential underlying causes. Consequently, it is unlikely that restless behaviors would be positively reinforced if they are not having the desired effect or targeting the issues from which restlessness developed. Furthermore, this model does not consider intra-personal or environmental factors that may increase vulnerability or the likelihood of responding to an activating event.

Reduced-stress threshold model

The reduced-stress threshold model, also known as the progressively lower stress threshold (PLST) or environmental vulnerability model, posits that an individual’s stress threshold is determined by the time he/she reaches adulthood, though changes in biological mechanisms can permanently or temporarily lower this threshold (Smith et al., 2004). As dementia progresses, individuals become increasingly vulnerable to the environment and experience the environment as more stressful. The lower threshold at which stimuli affect behavior can result in anxiety and behavioral symptoms, as a stimulus that is perceived as benign to a cognitively intact person may elicit a fearful reaction from a person with dementia (Cohen-Mansfield, 2000; Hall & Buckwalter, 1987). The undue distress caused by environmental factors, such as noise level, lighting, temperature, and crowdedness, may trigger a restless-type behavioral response such as fidgeting or repetitive movements. However, the reduced-stress threshold model cannot fully explain restless-type behaviors, as a person–environment misfit and a perceived stress level that exceeds a person with dementia’s individual threshold are more likely to result in agitation or anxiety, which are distinguished from restlessness in the literature.

Unmet needs model

The unmet needs model, also referred to as the needs-driven dementia-compromised behavior model, suggests that behavioral symptoms stem from attempts to communicate physical or psychic distress when unmet needs arise (Algase et al., 1996), as well as from the inability to use the environment appropriately to accommodate needs (Cohen-Mansfield, 2000). Research has shown that behaviors can result from the unmet needs in one of several ways: as an attempt to meet the need, an attempt to communicate the need, or as an outcome of having an unmet need (Cohen-Mansfield, 2000). This model is used frequently to design interventions for behavioral symptoms (Cohen-Mansfield, 2004). For example, some motoric symptoms of restlessness could be indicative of internal unrest due to an underlying need that cannot be easily communicated (e.g., due to aphasia). However, the unmet needs model cannot fully account for restless-type behaviors associated with dementia, as not all etiologies of restlessness are needs-based (e.g., direct effects of neuroanatomical changes, psychiatric causes). The most likely unmet needs driving restlessness may be boredom and physical discomfort, such as pain. Persons with aphasia often manifest restless behaviors that reflect in part an effort to communicate or alleviate the underlying pain (e.g., shifting, getting up and sitting down repeatedly, etc.).

The four models described above are not mutually exclusive and each may provide some insight into the etiology of restlessness. None, however, address the manifestation of restlessness in a comprehensive way. The apparent presence of multiple core features of restlessness (i.e., motor/ neurological component, psychiatric component, unmet needs component, environmental component) adds to the difficulty of neatly applying one of these prevailing theoretical frameworks to this behavior type. For example, certain core features of restlessness such as increased psychomotor activity may be due solely to biological changes in the brain, including changes to the dopaminergic systems (Engelborghs et al., 2008; Garand & Hall, 2000; Lanctôt, Herrmann, & Mazzotta, 2001), cholinergic deficits (Cummings & Beck, 1998), or functional network dysfunction (Balthazar et al., 2013). Other features of restlessness, such as non-productive or disorganized activity, may be due to the interplay of lowered stress threshold, environmental stressors, and personal characteristics. The purpose of the current paper is therefore not to add yet another definition of restlessness that will further complicate the field, but rather to recognize that the diversity in these four theoretical perspectives necessitates the need to synthesize a definition that is useful to many different paradigms.

Relationship of restlessness to other behaviors

Associated or co-occurring behaviors

To help distinguish restlessness from other behavioral manifestations, we examined relationships of behaviors among a sample of 509 dyads (caregivers and persons with dementia) by pooling samples from two separate trials, Project ACT and Project COPE (Gitlin et al., 2007, 2010), wherein behavioral symptoms were evaluated using the ABID.

We found (Table 2) that restlessness (defined as ‘restlessness, fidgetiness, inability to sit still’) was positively and significantly correlated with 10 behaviors with associations ranging from small to moderate: arguing (‘arguing, irritability, or complaining’; r = .339, p < .001), anxiety (‘worrying, anxiety, and/ or fearfulness’; r = .295, p < .001), waking the caregiver (‘waking and getting up at night’; r = .284, p < .001), destruction of property (r = .267, p < .001), agitation (‘easily agitated or upset’; r = .256, p < .001), delusions (‘incorrect, distressing beliefs or delusions’; r = .228, p < .001), hallucinations (‘seeing, hearing, or sensing distressing things that are not really present’; r = .153, p < .01), wandering (‘trying to leave home inappropriately’; r = .147, p < .01), rejection of care (‘refusing to accept appropriate help’; r = .107, p < .05), and crying out/ inappropriate screaming (r = .098, p < .05). Restlessness was not significantly correlated with five behaviors: verbal aggression, physical aggression, hurting self or others, inappropriate sexual behavior, or inappropriate social behavior (p > .05).

Table 2.

Restlessness correlated with other behavioral symptoms.

| Behavior | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Restlessness | 1.00 | .339c | .295c | .284c | .267c | .256c | .228c | .153c | .147c | .107a | .098a | .038 | .021 | .054 | .056 | .054 |

| (2) Arguing | 1.00 | .357c | .223c | .169c | .611c | .324c | .269c | .438c | .347c | .164c | .376c | .199c | .103a | .270c | .296c | |

| (3) Anxiety | 1.00 | .163c | .165c | .335c | .230c | .182c | .213c | .084 | .133b | .093a | .057 | −.004 | .051 | .055 | ||

| (4) Waking CG | 1.00 | .083 | .162c | .152b | .069 | .119b | .043 | .013 | .040 | −.01 | −.028 | .174c | .031 | |||

| (5) Destroying property | 1.00 | .164c | .243c | .196c | .167c | .029 | −.013 | .019 | .025 | .003 | .017 | .016 | ||||

| (6) Agitation | 1.00 | .392c | .344c | .347c | .232c | .205c | .279c | .180c | .030 | .094a | .272c | |||||

| (7) Delusions | 1.00 | .594c | .203c | .030 | .192c | .161c | .048 | −.017 | −.004 | .007 | ||||||

| (8) Hallucinate | 1.00 | .156c | .000 | .236c | .149b | .015 | .017 | −.026 | .199c | |||||||

| (9) Wandering | 1.00 | .261c | −.024 | .040 | .114a | −.010 | .348c | .251c | ||||||||

| (10) Refuse care | 1.00 | .088a | .370c | .225c | .087 | .072 | .142c | |||||||||

| (11) Crying out | 1.00 | .334c | .242c | −.014 | −.022 | .281c | ||||||||||

| (12) Verbal aggression | 1.00 | .364c | .019 | −.012 | .269c | |||||||||||

| (13) Physical aggression | 1.00 | .070 | .034 | .126c | ||||||||||||

| (14)Hurting self/others | 1.00 | .019 | .010 | |||||||||||||

| (15) Inappropriate sexual behavior | 1.00 | .174c | ||||||||||||||

| (16) Inappropriate social behavior | 1.00 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Bold font indicates statistical significance.

These correlations provide further insight as to the core features of restlessness and how this behavior type may be misidentified in measures and clinical practice. The correlations suggest that, in addition to a motoric/neurological component, restlessness may also be related to a psychiatric component, as evidenced by the strong correlations with anxiety, delusions, and hallucinations on the ABID, and a needs-based component, as indicated by the correlations with waking the caregiver, agitation, and wandering.

Distinct behavioral symptoms

In addition to identifying relevant behavioral scales, the extensive literature review also illuminated differential ‘diagnoses’ (e.g., behavioral symptoms, medical conditions) with which restlessness is often confused. These include the following behaviors and conditions with which restlessness has overlapping features, yet have been found to be of distinct behavioral types: wandering, agitation, anxiety, restless legs syndrome, delirium, and akathisia or other movement disorders (Table 3).

Table 3.

A comparison of the shared and unique elements of restlessness and other potential related behaviors.

| Restlessness | Wandering | Agitation | Anxiety | Restless legs syndrome |

Delirium | Akathisia/ movement disorders |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key elements of restlessness | |||||||

| Motor activity or motion | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Limited control | X | X | X | ||||

| Excessive or inappropriate | X | ||||||

| Non-productive or disorganized | X | X | |||||

| Subjective distress | X | ||||||

| Elements of potentially related behaviors | |||||||

| Temporally or spatially disordered locomotion | X | ||||||

| Attempts to leave/elope | X | ||||||

| Physiological effects of substance or medical condition | X | X | X | ||||

| Mental disorder | X | X | |||||

| Movement disorder | X | ||||||

| Impaired concentration | X | X | |||||

| Disturbance in attention and awareness | X | ||||||

| Acute onset/develops quickly | X | ||||||

| Tremor | X |

Algase, Yao, Beel-Bates, and Song (2007) clearly differentiated restlessness, wandering, and agitation, noting that, although these three phenomena share certain characteristics such as motor behavior, each construct has at least one unique characteristic. In contrast to restlessness, wandering is more likely to be needs-based, intentional, or goal-oriented, even if the goal is not easily discernible (Algase, Yao, et al., 2007; Thomas, 1995). Cohen-Mansfield and Billig (1986) noted that agitated behavior is always socially inappropriate, and may be abusive or aggressive toward self or others. Algase, Yao, et al. (2007) similarly described agitated behaviors as generally nonproductive, repetitious, and inappropriate to the circumstance with specific underlying states.

A major challenge is differentiating restlessness from anxiety. Similar to psychiatric disorders, there is often an overlap of symptoms among behavioral types in dementia. Anxiety is an internal state that may be accompanied by motoric symptoms in persons with and without dementia, of which restlessness may be one. Many examples of behaviors considered as restlessness could also refer to symptoms of anxiety, such as fidgeting, inability to sit still, pacing, hand-wringing, and hairpulling (Table 2). Anxiety symptoms occur in up to 75% of patients with dementia (Ballard et al., 2000; Chemerinski, Petracca, Manes, Leiguarda, & Starkstein, 1998; Gibbons, Teri, & Logsdon, 2002), and 5%–15% meet criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; Chemerinski et al., 1998; Starkstein, Jorge, Petracca, & Robinson, 2007). Calleo et al. (2011) did not find significant associations between GAD in persons with dementia and restlessness, but concluded that muscle tension and fatigue may be more important indicators of GAD in persons with dementia (Calleo et al., 2011). Although it can be difficult to distinguish dementia-related restlessness from anxiety with motoric symptoms, restlessness due to anxiety will presumably be accompanied by other symptoms that are not present when restlessness is due to dementia.

Restlessness associated with dementia is also categorically different from restless legs syndrome (RLS), a sensorimotor disorder that often has a profound impact on sleep (Walters, 1995). Differential diagnoses of RLS include nonspecific pacing or sleep disturbance associated with dementia, anxiety disorder, and neuroleptic-induced akathisia (Allen et al., 2003). The literature also differentiates restlessness from delirium, which is a neuropsychiatric syndrome that always has an underlying cause and is characterized by disturbances in attention and cognition with a fluctuating course (APA, 2013). Patients with hyperactive delirium demonstrate features of restlessness, agitation, and hyper vigilance, and often experience hallucinations and delusions (Fong, Tulebaev, & Inouye, 2009). Terminal, or pre-death restlessness, occurs in approximately 42% of dying patients (Enck, 1992; Wilden & Wright, 2002) and usually describes agitated delirium in a dying patient, indicating central nervous irritability as evidenced by multifocal myoclonus, convulsions, impaired consciousness, confusion, mental agitation, moaning, and physical restlessness (Burke, 1997).

Akathisia is a movement disorder characterized by the compulsion to be in constant motion, restlessness, and severe discomfort (primarily in the legs). The leading cause of akathisia is the initiation or rapid increase of traditional antipsychotics (i.e., neuroleptics), although it can also manifest as a side effect of withdrawal from benzodiazepines (Haddad & Dursun, 2008). The most common movement disorder is essential tremor, which is defined as a monosymptomatic neurological disorder characterized by rhythmic shaking of the hands, although shaking can also affect the head, voice, face, and legs (Plumb & Bain, 2007). Essential tremor is differentiated from Parkinson’s disease (PD), which is a neurodegenerative disorder whose progressive movement-related symptoms are clearly differentiated from restless associated with dementia.

An emerging definition of restlessness

Based on existing definitions, the literature review of scales, and our exploratory analyses, we propose three core features in which all three must be present for the behavior to be characterized as restlessness:

-

(1)

Diffuse motor activity or motion subject to limited control (e.g., pacing, fidgeting, repetitive motor movements) that is judged by a clinician, caregiver, or observer to be excessive and/or inappropriate to the circumstances.

-

(2)

The behavior(s) is(are) generally non-productive or disorganized, failing to appropriately address or target potential underlying causes such as boredom.

-

(3)

The behavior(s) is(are) associated with a degree of subjective distress (e.g., nervousness, discomfort) that is either communicated by the person with dementia or extrapolated from the behavior itself.

In turn, restlessness should be considered distinct from or not attributable to:

-

(1)

The temporally and/or spatially disordered locomotion that is the hallmark of wandering behavior, and is not associated with attempts to elope or leave without permission of caregivers from an institution or home.

-

(2)

The physiological effects of a substance (e.g., neuroleptic medication, withdrawal from benzodiazepines) or another medical condition (e.g., hypoglycemia).

-

(3)

A mental disorder other than dementia (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder) or movement disorder (e.g., restless legs syndrome, essential tremor, Parkinson’s disease).

-

(4)

The context of a delirium or at end-of-life.

Specify if: During the daytime or nighttime.

Discussion

Restlessness appears to be a common and upsetting behavior associated with dementia, but it has yet to be clearly characterized or consistently operationalized in behavioral scales. Conceptual and operational confusion has muddled an understanding of its prevalence, and has hindered intervention development and assessment of caregiver needs. Indeed, our review of the literature revealed enormous variations in the categorization and definition of dementia-related restlessness. Particularly striking was the finding that the ambiguity of the term restlessness was first identified at least 20 years ago (Kolanowski, 1991), and yet there has been no significant progress towards operationalizing this term. This may reflect limited awareness of the importance of monitoring behavioral symptoms in dementia and ensuring that interventions are appropriately targeted.

The current study was undertaken in order to advance a definition of restless-type behaviors and provide recommendations for future directions in research, measurement, and intervention development in this area. Based on a systematic review of existing definitions, fit with theoretical frameworks and preliminary data from a sample of community-living persons with dementia, we have proposed a provisional definition of dementia-related restlessness as a pathway to standardization of the application of the term, its measurement, and clinical designation. This definition identifies three core clinical features of restlessness considered to be most important diagnostically and four ways in which it should be distinguished from other behavioral occurrences. In the spirit of DSM-5, each of the three diagnostic criteria would need to be met in order for adequate sensitivity and specificity for identifying clinically meaningful restlessness. Our intent in this paper is to provide the conceptual basis for these criteria. Our definition of restlessness is specific to dementia, which is a key differentiation from previous attempts to define this construct. Repetitive behaviors occurring outside of a formal diagnosis of dementia were not included in our proposed definition.

Although there is overlapping pathology with restlessness as we have defined it and other behavioral symptoms of dementia (e.g., agitation), it is the composite of features in our definition that will assist observers in identifying and measuring its occurrence. As is sometimes the case with diagnostic criteria, there will likely be some individuals who meet some but not all of the criteria. It may be that these individuals should be monitored for the potential of developing restlessness and that consideration be given to strategies to address the elements of restlessness that are present as part of a treatment plan.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the most extensive analysis of dementia-related restlessness and its continued ambiguity to date. Potential limitations of this analysis include the possibility that not all assessments that include restlessness were captured by the parameters, search terms, and databases used in the literature review. However, the literature incorporated into this study effectively illustrate the lack of operationalization of dementia-related restlessness and the resulting adverse effects on comparability of research findings, targeted interventions, and clinical practice.

The next step is to operationalize restlessness according to our proposed definition in order to test its validity. As the need for a standardized diagnostic tool for use in clinical research on restlessness is critical, future research will focus on the development and testing of a psychometrically sound assessment tool to measure and quantify dementia-related restlessness. Additionally, as there is increasing evidence that behavioral symptoms of dementia are caused in part by dysfunction in specific brain networks (e.g., Greicius, 2008; Menon, 2011; Rosenberg, Nowrangi, & Lyketsos, 2015), future research should further examine the underlying neural circuitry of restlessness and related behavioral symptoms. Given the confusion in definition, etiology, and measurement of dementia-related restlessness identified herein, the relationships among restlessness and other behaviors as well as anosognosia are unclear and should be the focus of future research. Appropriate interventions (nonpharmacological and pharmacological) for persons with dementia are contingent on an accurate understanding of behavioral symptoms (including detection and differentiation from other behaviors), and standardized language is crucial to the establishment of validity in restlessness-related research.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aalten P, van Valen E, Clare L, Kenny G, Verhey F. Awareness in dementia: A review of clinical correlates. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9:414–422. doi: 10.1080/13607860500143075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biological Psychiatry. 1988;23:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algase DL, Antonakos C, Yao L, Beattie ER, Hong GR, Beel-Bates CA. Are wandering and physically nonaggressive agitation equivalent? American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16:293–299. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181629943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algase DL, Beck C, Kolanowski A, Whall A, Berent S, Richards K, Beattie E. Need-driven dementia-compromised behavior: An alternative view of disruptive behavior. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 1996;11:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Algase DL, Moore DH, Vandeweerd C, Gavin-Dreschnack DJ. Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging & Mental Health. 2007;11:686–698. doi: 10.1080/13607860701366434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algase DL, Yao L, Beel-Bates CA, Song J. Theoretical models of wandering. In: Nelson A, Algase DL, editors. Evidence-based protocols for managing wandering behaviors. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Allen NH, Gordon S, Hope T, Burns A. Manchester and Oxford Universities Scale for the Psychopathological Assessment of Dementia (MOUSEPAD) British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;169:293–307. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisi J The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Medicine. 2003;4:101–119. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Association facts and figures 2015. 2015 Retrieved May 1, 2015, from http://www.alz.org/facts/downloads/facts_figures_2015.pdf.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C, Neill D, O’Brien J, McKeith IG, Ince P, Perry R. Anxiety, depression, and psychosis in vascular dementia: Prevalence and associations. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;59:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazar MLF, Pereira FRS, Lopes TM, da Silva EL, Coan AC, Campos BM, Cendes F. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease are related to functional connectivity alterations in the salience network. Human Brain Mapping. 2013;35:1237–1246. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks S, Weintraub S. Self-awareness and self-monitoring of cognitive and behavioral deficits in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, primary progressive aphasia, and probable Alzheimer’s disease. Brain and Cognition. 2008;67:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten M, Becker R, Gauthier S. Validity and reliability of the dementia behavior disturbance scale. Journal ofthe American Geriatrics Society. 1990;38:221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AL. Palliative care: An update on “terminal restlessness”. Medical Journal of Australia. 1997;166:39–42. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb138702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleo JS, Kunik ME, Reid D, Kraus-Schuman C, Paukert A, Regev T, Stanley M. Characteristics of generalized anxiety disorder in patients with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2011;26:492–497. doi: 10.1177/1533317511426867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemerinski E, Petracca G, Manes F, Leiguarda R, Starkstein SE. Prevalence and correlates of anxiety in Alzheimer’s disease. Depression and Anxiety. 1998;7:166–170. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:4<166::aid-da4>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J. Theoretical frameworks for behavioral problems in dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly. 2000;1:8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: A review, summary, and critique. Focus. 2004;2:288–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Billig N. Agitated behaviors in the elderly: I. A conceptual review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1986;34:711–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb04302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS. A description of agitation in a nursing home. Journal of Gerontology. 1989;44:M77–M84. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.3.m77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Beck C. The cholinergic hypothesis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1998;6(Suppl.):S64–S78. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199821001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, Sancarlo D, Panza F, Copetti M, Cascavilla L, Paris F, Pilotto A. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional status in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia patients. Current Alzheimer Research. 2012;9:759–771. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carolis A, Cipollini V, Corigliano V, Comparelli A, Sepe-Monti M, Orzi F, Giubilei F. Anosognosia in people with cognitive impairment: Association with cognitive deficits and behavioral disturbances. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2015;5:42–50. doi: 10.1159/000367987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vugt ME, Stevens F, Aalten P, Lousberg R, Jaspers N, Verhey FR. A prospective study of the effects of behavioral symptoms on the institutionalization of patients with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics. 2005;17:577. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205002292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanand DP, Brockington CD, Moody BJ, Brown RP, Mayeux R, Endicott J, Sackeim HA. Behavioral syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics. 1992;4:161–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanand DP, Miller L, Richards M, Marder K, Bell K, Mayeux R, Stern Y. The Columbia University Scale for Psychopathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Neurology. 1992;49:371–376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530280051022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachman DA, Swearer JM, O’Donnell BF, Mitchell AL, Maloon A. The Caretaker Obstreperous-Behavior Rating Assessment (COBRA) scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:463–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enck RE. The last few days. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 1992;9:11–13. doi: 10.1177/104990919200900403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelborghs S, Vloeberghs E, Le Bastard N, Van Buggenhout M, Marien P, Somers N, De Deyn PP. The dopaminergic neurotransmitter system is associated with aggression and agitation in frontotemporal dementia. Neurochemistry International. 2008;52:1052–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Nature Reviews: Neurology. 2009;5:210–220. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garand L, Hall GR. The biological basis of behavioral symptoms in dementia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2000;21:91–107. doi: 10.1080/016128400248284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, Newcomer R. Unmet care needs and key outcomes in dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:2098–2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons L, Teri L, Logsdon R. Anxiety symptoms as predictors of nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2002;8:335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308:2020–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.36918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Marx KA, Stanley IH, Hansen BR, Van Haitsma KS. Assessing neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia: A systematic review of measures. International Psychogeriatrics. 2014;26:1805–1848. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, Hauck WW. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: The COPE randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:983–991. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hauck WW. A non-pharmacological intervention to manage behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and reduce caregiver distress: Design and methods of project ACT. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2007;2:695–703. doi: 10.2147/cia.s1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfries CG, Bråne G, Gullberg B, Steen G. A new rating scale for dementia syndromes. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 1982;1:311–330. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(82)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius M. Resting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. Current Opinions in Neurology. 2008;21:424–430. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328306f2c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad PM, Dursun SM. Neurological complications of psychiatric drugs: Clinical features and management. Human Psychopharmacology. 2008;23(Suppl. 1):15–26. doi: 10.1002/hup.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. Progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1987;1:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood DG, Sultzer DL, Wheatley MA. Impaired insight in Alzheimer’s disease: Association with cognitive deficits, psychiatric symptoms, behavioral disturbances. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, & Behavioral Neurology. 2000;13:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb DO. Drives and the CNS (conceptual nervous system) Psychological Review. 1955;62:243–254. doi: 10.1037/h0041823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins RW, Kilik LA, Day DJA, Bradford L, Rows CP. The Kingston Standardized Behavioural Assessment. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2006;21:339–346. doi: 10.1177/1533317506292576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT. Anatomical changes underlying dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Research and perspectives in Alzheimer’s disease. In: Jucker M, Beyreuther K, Haass C, Nitsch R, Christen Y, editors. Alzheimer and beyond. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S, Streim JE, Saliba D. A conceptual framework for rejection of care behaviors: Review of literature and analysis of role of dementia severity. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos C. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in community-dwelling patients: The need for a tailored patient- and- caregiver-centered approach. British Medical Journal. 2015;350:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A, Nadkarni N, Davidson W, Thomas AW. The Frontal Behavioral Inventory in the differential diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2000;6:460–468. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700644041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber-Riel W. Activation research: Psychobiological approaches in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research. 1979;5:240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski AM. Restlessness in the elderly: A concept analysis. Washington, DC: NLN Publications; 1991. pp. 345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, Mazzotta P. Role of serotonin in the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2001;13:5–21. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefroy RB, Hobbs MST, Hyndman J. Rating scales in residential care for elderly people: The Crichton Royal Behavioural Rating Scale. Australasian Journal on Aging. 1992;11:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley D. Emotion. In: Stevens SS, editor. Handbook of experimental psychology. New York: Wiley; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, Teri L, Weiner MF, Gibbons LE, Raskind M, Peskind E, Thal LJ. Assessment of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease: The agitated behavior in dementia scale. Alzheimer’s disease cooperative study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47:1354–1358. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreck DJ, Bylsma FW, Folstein MF. The Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale: A new scale for comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in Alzheimer’s disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1994;2:60–74. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199400210-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: Results from the cardiovascular health study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1475–1483. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane R. What are the syndromes of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia? International Psychogeriatrics. 2000;12:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: A unifying triple network model. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2011;15:483–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitty E, Flores S. Assisted living nursing practices: The language of dementia: Theories and interventions. Geriatric Nursing. 2007;28:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy DW, Bédard M, Guyatt GH, Lever J. Dysfunctional behavior rating instrument. International Psychogeriatrics. 1996;8:333–341. doi: 10.1017/s104161029700358x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Weiler P, Franzi C, Henry R. Assessment of disruptive behavior associated with dementia: The disruptive behavior rating scales. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 1989;2:196–202. doi: 10.1177/089198878900200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murman DL, Chen Q, Powell MC, Kuo SB, Bradley CJ, Colenda CC. The incremental direct costs associated with behavioral symptoms in AD. Neurology. 2002;59:1721–1729. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036904.73393.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris CM. Restlessness: A nursing phenomenon in search of meaning. Nursing Outlook. 1975;23:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenheimer G, Borson S, Sanders AE, Swain-Eng RJ, Kyomen HH, Tierney S, Johnson J. Quality improvement in neurology. Neurology. 2013;81:1545–1549. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a956bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters ME, Schwartz S, Han D, Rabins PV, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Lyketsos CG. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as predictors of progression to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and death: The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;172:460–465. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14040480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumb M, Bain P. Essential tremor. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Profenno LA, Tariot PN, Ismail MS. Treatments for behavioral and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. In: Burns A, O’Brien J, Ames D, editors. Dementia. London: Edward Arnold; 2005. pp. 482–498. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, De Deyn PP, Katz I, Brodaty H, Cohen-Mansfield J. Factor analysis of the Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory in three large samples of nursing home patients with dementia and behavioral disturbance. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:991–998. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER. Neurobiologic bases of noncognitive behavioral problems in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Disease and Associated Disorders. 1994;8(Suppl. 3):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray WA, Taylor JA, Lichtenstein MJ, Meador KG. The nursing home behavior problem scale. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47:M9–M16. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.1.m9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, Ferris SH, Franssen E, Georgotas A. Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Phenomenology and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1987;48(Suppl):9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J, Burgio L, Kollar M, Cain M, Allison M, Fogleman M, Zubenko GS. The Pittsburgh agitation scale: A user-friendly instrument for rating agitation in dementia patients. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1994;2:52–59. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199400210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis CL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg PB, Nowrangi MA, Lyketsos CG. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: What might be associated brain circuits? Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2015;(43–44):25–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev P, Kruk J. Restlessness: The anatomy of a neuropsychiatric symptom. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;30:38–53. doi: 10.3109/00048679609076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha D, Zemlan FP, Nelson S, Bienenfeld D, Thienhaus O, Ramaswamy G, Hamilton S. A new scale for assessing behavioral agitation in dementia. Psychiatry Research. 1992;41:73–88. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Gerdner LA, Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. History, development, and future of the progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for dementia care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:1755–1760. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel R, Brunner C, Ermini-Fünfschilling D. A new behavioral assessment scale for geriatric out- and in-patients: The NOSGER (Nurses’ Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients) Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1991;39:339–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein S, Jorge R, Petracca G, Robinson R. The construct of generalized anxiety disorder in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:42–49. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000229664.11306.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultzer DL, Levin HS, Mahler ME, High WM, Cummings JL. Assessment of cognitive, psychiatric, and behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia: The Neurobehavioral Rating Scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:549–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland T, Alterman IS, Yount D, Hill JL, Tariot PN, Newhouse PA, Cohen RM. A new scale for the assessment of depressed mood in demented patients. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145:955–959. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.8.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tampi RR, Williamson D, Muralee S, Mittal V, McEnerney N, Thomas J, Cash M. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: Part I epidemiology, neurobiology, heritability, and evaluation. Clinical Geriatrics. 2011;19:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, Edland SD, Weiner MF, Fillen-baum G, Stern Y. The behavior rating scale for dementia of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1349–1357. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L. Assessment and treatment of neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms in cognitively impaired older adults: Guidelines for practitioners. Seminar in Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 1997;2:152–158. doi: 10.1053/SCNP00200152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DW. Wandering: A proposed definition. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1995;21:35–41. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19950901-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tija J. Patients with advanced dementia continue receiving medications of questionable benefit. JAMA Internal Medicine Releases. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4103. Retrieved October 10 2014, from http://media.jamanetwork.com/news-item/patients-with-advanced-dementia-continue-receiving-medications-of-questionable-benefit/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tija J, Rothman MR, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Holmes HM, Sachs GA, Mitchell SL. Daily medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58:880–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victoroff J, Nielson K, Mungas D. Caregiver and clinician assessment of behavioral disturbances: The California Dementia Behavior Questionnaire. International Psychogeriatrics. 1997;9:155–174. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters AS. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome: The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Movement Disorders. 1995;10:634–642. doi: 10.1002/mds.870100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilden BM, Wright NE. Concept of pre-death restlessness in dementia. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2002;28:24–29. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20021001-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Dementia fact sheet. 2015 Retrieved May 1, 2015, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs362/en/

- Zuidema SU, Derksen E, Verhey FRJ, Koopmans RTCM. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in a large sample of Dutch nursing home patients with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:632–638. doi: 10.1002/gps.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]