Abstract

MSM continue to represent the largest share of new HIV infections in the United States each year due to high infectivity associated with unprotected anal sex. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) has the potential to provide a unique view of how high-risk sexual events occur in the real world and can impart detailed information about aspects of decision-making, antecedents, and consequences that accompany these events. EMA may also produce more accurate data on sexual behavior by assessing it soon after its occurrence. We conducted a study involving 12 high-risk MSM to explore the acceptability and feasibility of a 30 day, intensive EMA procedure. Results suggest this intensive assessment strategy was both acceptable and feasible to participants. All participants provided response rates to various assessments that approached or were in excess of their targets: 81.0 % of experience sampling assessments and 93.1 % of daily diary assessments were completed. However, comparing EMA reports with a Timeline Followback (TLFB) of the same 30 day period suggested that participants reported fewer sexual risk events on the TLFB compared to EMA, and reported a number of discrepancies about specific behaviors and partner characteristics across the two methods. Overall, results support the acceptability, feasibility, and utility of using EMA to understand sexual risk events among high-risk MSM. Findings also suggest that EMA and other intensive longitudinal assessment approaches could yield more accurate data about sex events.

Keywords: Ecological momentary assessment, MSM, Sex risk, Assessment, Alcohol use, Drug use

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) account for the largest share of new HIV infections, both in the United States and internationally [1, 2]. These rates are driven in part by high infectivity associated with unprotected anal intercourse (UAI; 1), and a majority of new infections occur among a subset of particularly high-risk MSM who have UAI with many partners [3].

A fine-grained understanding of the contexts in which sexual HIV-risk behaviors occur is needed to inform prevention approaches that adequately address risk factors. Research devoted to understanding these behaviors and their contexts has been ongoing for several decades and has used a variety of methods to assess sexual behaviors. Nearly all existing methods rely on self-report, but most past approaches have required participants to recall behaviors and events over weeks or months. For example, cross-sectional studies are plentiful [e.g., 4–6], but most involve asking participants to aggregate their involvement in various behaviors over long recall periods (e.g., 6 months) to study risk behavior. With such a broad approach, it is difficult to understand these behaviors in detail and there may be significant errors in recalling and “adding up” events [7, 8]. Fine-grained, cross-sectional recall approaches like Timeline Followback (TLFB; 9, 10) afford a higher level of “resolution,” and many studies have shown that test–retest reliability of sexual behavior reports on the TLFB are high [11–14]. However, most of these reliability studies compare responses on TLFBs that have been collected anywhere from hours to 5 days apart, showing primarily that participants are able to provide similar responses across administrations. They do not show that participants can accurately recall what happened and when behaviors occurred. This may be a particularly critical limitation for studies exploring the co-occurrence of other behaviors (e.g., alcohol/drug use) with high-risk sex, since these studies depend on the precise assessment of unique behaviors occurring on specific days/times. TLFB methods also frequently require participants to recall the distant past, with past studies assessing target behaviors over periods ranging from 30 to 90 days.

The potential for recall errors increases when target behaviors are frequent and the recall window is long [8]. For high risk MSM, sexual behavior is inherently a high-frequency event. Moreover, while past studies suggest that repertoires and patterns of sexual behavior (e.g., types of sex, contraceptive use) may develop in the context of long-term sexual partnerships [15, 16], high risk MSM often have many casual sexual partners which may result in substantial variability in behavior across sex events and partnerships. Studying aspects of these high-frequency, high-variability events in the natural environment of high risk MSM may therefore require methods capable of assessing these events in as close to real time as possible.

Daily diary methods have emerged as one such approach. These methods ask participants to record daily logs of their behavior using paper-and-pencil forms, phone interviews/systems, text messaging, or online surveys. These methods have been employed to study day-to-day sexual behavior in a variety of samples, including adolescents, college students, and adults, as well as MSM, with monitoring periods ranging from 14 to 420 days [17–22]. In general, while daily diary methods likely yield more accurate data compared to recall-based methods, to be useful, they require participants to respond to an acceptable number of daily surveys, preferably on (or close to) the day on which they were assigned. Several past reports suggest that, with appropriate attention to procedures and incentives that encourage adherence, conducting online daily diary studies is feasible among heterosexual adolescents, college students, and adults, yielding response rates ranging from 60–92 % [18, 19, 23, 24]. To date, four unique studies have been conducted with MSM over intervals of 30–90 days, with response rates ranging from 78–84 % [22, 25–27].

The advent of sophisticated mobile computing technologies offers important improvements in intensive longitudinal methodology. The ubiquity of smartphones and personal electronic devices [28] allows participants to provide behavioral data on devices they carry with them everywhere as they go about their daily lives. Despite its advantages, some question the accuracy of data collected in this way [29]. One study that used smartphones to assess sexual behavior among high-risk MSM provides some support for these concerns, showing that total rates of sexual behaviors reported via smartphone exhibited low reliabilities when compared with 2-week recall measures [30]. However, the recall measures used required participants to aggregate behaviors over 2-weeks, which can introduce bias [8, 31]. Additionally, these authors did not assess whether the timing of sex events was accurately reported across methods, which is critical in studies that explore in the co-occurrence between various risk factors (e.g., alcohol/drug use) and HIV-risk behavior.

Use of ubiquitous technologies in longitudinal research can also allow researchers to assess experience more frequently than once each day, providing valuable information about dynamic and proximal influences on sexual decision-making that occur throughout each day. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) refers to a set of longitudinal methods that typically incorporates some combination of (1) daily diary methodology, (2) event-contingent responding, and (3) experience sampling [32]. Daily diary methods typically ask respondents to complete entries once each day. Event contingent responding asks participants to initiate reports as specific behaviors of interest have occurred [33], which may be best suited for studies in which the behavior of interest is discrete (it has a well-defined beginning and end) and/or when it is critical to assess phenomena as the behavior occurs [34, 35]. Experience sampling aims to collect a pseudo-representative sample of experiences by prompting participants to respond at random intervals over a given time period (e.g., waking hours of each day) [36]. This may be best suited for situations when rapidly fluctuating, dynamic phenomena (e.g., affect, attitudes, plans) are of interest [32]. EMA studies that employ a combination of these assessment techniques have the potential to considerably expand our understanding of the characteristics, antecedents, and consequences of high-risk sexual behavior particularly among at-risk groups (like MSM who have many partners). A clear strength of assessing behavior and experiences via smartphone in near real-time using EMA approaches is the potential it has for generating a more refined and valid understanding of whether experiences occurring around the time of sexual risk behavior may have contributed to its occurrence. Answering these kinds of questions requires an assessment tool that yields more precise information about the timing of events that recall-based methods (e.g., TLFB) are not suitable for and are more difficult to capture via once-a-day assessments. For example, it is well-known that alcohol and drug use on a given day is associated with HIV-risk behavior among MSM [37–39], but little is known about the psychological and environmental characteristics of drinking events that ultimately involve HIV-risk behavior among MSM. Improving this knowledge could unearth important targets for interventions aimed at reducing risk, but little is known about whether collecting such intensive longitudinal data are acceptable and feasible among high-risk MSM.

To date, only one study has explored the acceptability and feasibility of collecting such intensive longitudinal data, and did so in a sample of 16 African American MSM [40]. For 30 days, participants were asked to complete a signal-prompted daily diary survey each day at 9 a.m., 3 experience sampling prompts per day (between 10 a.m. and 10 p.m.), and event-contingent assessments that were to be initiated by participants after finishing a “cluster of alcohol use in one sitting.” Of those approached, 94 % agreed to participate, and participants completed 81 % of daily prompts and 75 % of random prompts, providing evidence of acceptability and feasibility. The authors also addressed “reactivity” due to the assessment procedure, which refers to the “potential for behavior […] to be affected by the act of assessing it” (p. 20; 8). While they concluded there was little evidence for this, the number of drinking events reported declined across the study period, suggesting that “fatigue” may have been an issue. However, as the study authors point out, the acceptability, feasibility, and reactivity in EMA protocols likely depends on a number of study characteristics, including the intensity of monitoring, signaling strategy, and participant management procedures (e.g., target response rates, response rate feedback methods and intervals, incentive schedules). Thus, EMA studies should be carefully designed while considering the optimal combination and timing of assessments needed to capture the behaviors/experiences of interest while achieving optimal response rates and accuracy.

We conducted a study to explore the acceptability, feasibility, and reactivity associated with an EMA procedure that was designed to gather detailed data on alcohol/drug use and HIV-risk behavior among high-risk MSM in the northeastern United States. We also examined the potential benefits in accuracy associated with assessing alcohol/drug use and sexual behavior via daily diary (compared with fine-grained recall methods, like TLFB).

Method

Participants

Twelve participants were recruited from the Providence, Rhode Island area during 3 months of active recruitment. Eligible participants were (1) males, (2) over age 18, who (3) self-reported being HIV-negative, and (4) reported at least one occasion of unprotected (condomless) anal sex with a casual male partner in the past 30 days. Since one of the focal goals of the study was to improve understanding of alcohol use and HIV risk behavior, eligible participants were also “at-risk” drinkers (either consuming 14+ drinks in the last week, or 5+ drinks on a single occasion in the past month; NIAAA, 41). Participants were ineligible if they were (1) currently on a pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimen, (2) engaged in any injection drug use in the past 3 months, (3) were not fluent in english, (4) were currently receiving alcohol/drug treatment, and (5) had been diagnosed with serious mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder). Participants enrolled in our study were between 22 and 50 years old (M = 30, SD = 8.8). Two of these participants were Hispanic, and ten were White.

All participants were recruited via a popular smartphone application commonly used by gay men to meet romantic and sexual partners. During this time, 95 participants were screened for eligibility, 20 of whom were eligible (21 %). Four of these declined to participate/did not respond to further inquiries, 12 were enrolled, and 4 were interested, but budget constraints prevented further enrollment. This corresponds to an 80 % (16/20) acceptance rate.

Procedures

Participants were instructed to complete 3 types of assessments over a 30 day period: (1) A self-initiated, daily diary assessment, to be completed upon waking each day (but open for 12 h, “morning assessment”), (2) 6 signal-prompted experience sampling assessments per day, delivered automatically and at a random time within each 2.5 h window between 9 a.m. and 12 midnight each day (“random prompts”), and (3) a self-initiated, event-contingent assessment to be completed when beginning to drink and/or use drugs on a given day (“drinking/drug use episode assessment”).

Participants were first screened online before being contacted by a research assistant (RA) to schedule an in-person appointment. At their appointments, RAs reviewed the study procedures and obtained informed consent before asking participants to complete several computerized baseline measures (including a TLFB of drinking, drug use, and sexual behavior over the preceding 30 days). Then, RAs issued participants a study-provided smartphone (LG Optimus Logic © running Android 2.3 Gingerbread) equipped with movisensXS © [GmbH] software and a charger. RAs then provided thorough training on the smartphone and software’s features and walked participants through a typical day on the study, demonstrating how to initiate various types of assessments and explaining the meaning of each of the items involved (e.g., for items asking about “standard drinks,” this means 12 oz. beer, 5 oz. wine, 1 oz. liquor). Participants were coached to achieve response rates to random prompts of 80 % or greater, and to complete 100 % of morning assessments. Since the goal of this study was to understand influences on sexual risk behavior (which was assessed via the morning assessment), we chose a 100 % target response rate for these assessments to maximize the availability of data on sex events. We chose an 80 % target response rate for random prompts to minimize missing data and align with similar benchmarks used in past EMA research [42–45]. Several procedures were implemented by RAs to help participants achieve these response rates, including: (1) building rapport, (2) soliciting buy-into the study (e.g., conveying the importance of the data to understanding behavior, asking for their investment), (3) discussing strategies that can enhance response rates/quality (e.g., “get into a routine, make sure the ringer volume is high, keep the phone with you whenever possible”), and (4) emphasizing confidentiality of responses. Finally, RAs troubleshot potential individual barriers to adherence (e.g., demonstrated how to briefly delay prompts during work or when otherwise occupied). Participants were instructed to contact research staff should their study-provided smartphones become lost or stolen. They were informed that a fee for lost devices could be deducted from their payment balance for lost devices ($50 for smartphone, $10 for charger). While data were briefly stored in the internal memory of smartphones (before being uploaded to centralized servers once a day), these data were de-identified, and lost/stolen devices were remotely locked and erased using Android Device Manager (Google, Inc.). Only one participant reported losing their smartphone.

Each week throughout the study period, summary data on individual response rates to random prompts and morning assessments were calculated. Feedback on each participant’s response rates were then provided via email and messages through the smartphone software. While email messages provided details about participants’ response rates, target rates, and “tips” for improving their adherence, messages sent through the movisensXS software briefly provided both random and morning assessment response rates and referred participants to their email for further information. If participants had response rates lower than target levels, RAs contacted participants by phone to provide coaching, troubleshoot issues, and encourage consistent responding.

At the end of the 30-day EMA period, participants returned for a follow-up in-person appointment to complete a follow-up TLFB on the computer, which covered the same 30-day period assessed during the EMA study portion. Participants also returned their equipment, received final feedback on response rates, and were paid. Payments were determined based on response rates: They earned $2 for each morning assessment, plus a “bonus” of $10 for every 10 days all these assessments were completed, as well as $0.50 for each random assessment completed, with a “bonus” of $10 for every 10 days they completed >80 % of these. As such, participants could earn a total of $210 over the course of the study.

Measures

Sexual behavior on each day during the EMA protocol was assessed via morning assessments initiated upon waking on the following day. Participants could report up to 4 partners per day. Items asked about characteristics of each partner (gender, casual vs. regular, perceived HIV-status [negative, positive, don’t know], whether it was a new partner, the length of time they knew them [just met to more than a year], where they met them [e.g., online, through friends]), sexual behaviors they engaged in (oral, insertive anal, receptive anal, vaginal), and whether or not a condom was used with each act. TLFBs collected at the beginning and end of the 30 days assessed sexual behavior similarly [9, 10]. That is, using a calendar of the last 30 days, participants recorded up to 4 partners per day, and reported on the characteristics of each (gender, casual vs. regular, HIV-status), sex acts performed (oral, insertive/receptive anal, vaginal sex), condom use for each act, and whether they were under the influence of alcohol/drugs during each. The appearance and wording of items in the TLFB were designed to match those asked via EMA.

Alcohol use was assessed in the EMA protocol in two ways: In random assessments, participants were asked how many standard drinks they consumed since the last random prompt and their current level of intoxication ([1] not at all to [10] more intoxicated than I’ve ever been). In the morning assessment, participants were asked to indicate how many standard drinks they consumed the day before (from first to last drink), the number of hours over which they drank, and their highest level of intoxication. The TLFB completed at the end of the 30 day period also assessed the number of standard drinks consumed on each day and the number of hours over which drinking occurred.

Drug use was similarly assessed in the EMA portion. In random assessments, participants were asked to indicate if they had used drugs since the last random prompt, and if so, which they used (e.g., marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine), and how high they were currently ([1] “not at all high” to [10] “more high than I’ve ever been”). In morning assessments, participants were asked to indicate whether they used drugs the day before, and if so, which drugs, and the most high they were. Again, data from the morning assessment was used in the following analyses. The TLFB at the end of the 30 days assessed drug use similarly, asking participants to indicate which drugs they used on each day.

Data Analysis

To address feasibility and adherence to study procedures, total response rates over the 30-day study period were calculated for each survey type as well as the average time it took to complete each. We also plotted response rates to each assessment by study day to explore whether there were systematic changes across the study period. A common concern about the feasibility of conducting EMA research on alcohol use is the potential for response rates and quality to decline when participants have been drinking. As such, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE; Stata Corp., 2013) to explore whether the percentage of completed random prompts varied depending upon whether or not the participant had been drinking and their level of alcohol use on a given day. To examine evidence of reactivity, we compared mean frequencies of sex and drinking/drug use events reported on the baseline TLFB (or behavior in the 30 days prior to enrolling) with the follow-up version of the TLFB (behavior in the 30 days while on EMA). GEE models were estimated to explore whether reports of sex and drinking events changed systematically across the EMA study period. We also plotted sex/drinking behaviors by study day, fitting Lowess curves to these data to aid in visualizing any trends.

Next, we explored whether utilizing components of EMA might improve the accuracy of sex and alcohol/drug use behavior reports compared with existing assessment techniques that rely on recall (e.g., TLFB). We compared total and day level reports of these behaviors collected on the EMA morning assessment (daily diary) to the same reports collected on the follow-up TLFB. EMA morning assessment and TLFB data were matched using the dates automatically recorded in the software used for each assessment. Since EMA morning assessments measured behaviors the previous day, reports were adjusted so that both reflect events occurring on the same day (i.e., EMA morning assessments measure the previous day). We calculated the absolute agreement between the two methods about whether sex behaviors (e.g., any sex, anal sex, etc.), alcohol use, and drug use occurred each day. We also calculated intra-class correlations (ICCs) between EMA morning assessment ratings and the TLFB [46, 47]. To visualize these comparisons, scatterplots of total “count” of each behavior (across the 30 days) were plotted by assessment method. Finally, one of the key uses of intensive longitudinal research designs is to explore whether outcomes of interest (e.g., HIV risk behavior) and risk factors occur around the same time. This relies on participants being able to recall not only that specific behaviors occurred in a given time window but exactly when each behavior occurred. Thus, for each sex event reported by each participant via EMA, we calculated the frequency of events that matched across assessment methods and were reported on the correct day (“correct reports”), those that matched but were reported on adjacent days (“near misses”), and those that did not match or were not reported on the same or adjacent day. For this calculation, variables indicating a combination of all sexual behaviors engaged in with a given partner (oral, insertive and/or receptive anal sex), and many partner characteristics (number of partners, whether each was new, their HIV status) were used to identify specific types of events and categorize them.

Results

Adherence to Study Procedures

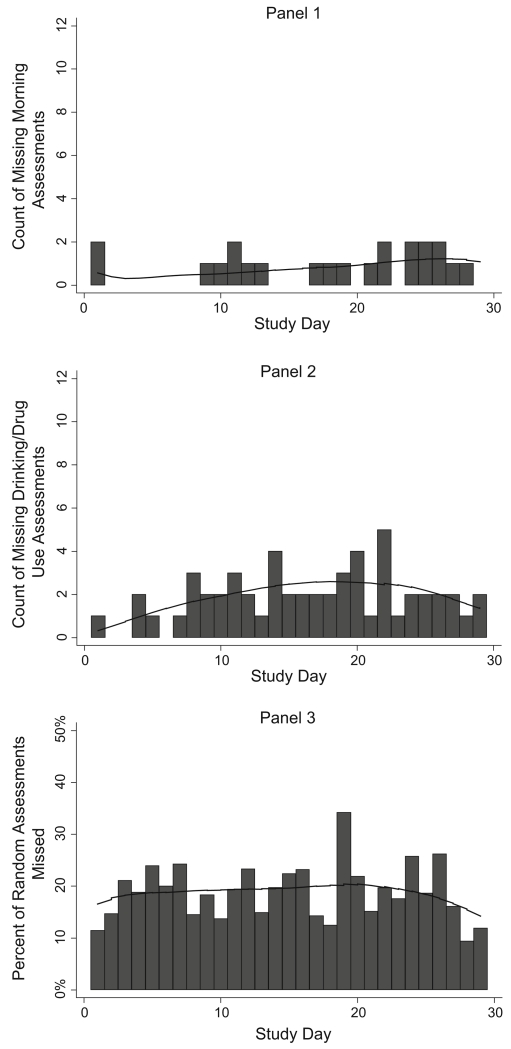

Over the study period, participants provided an average of 29.4 (SD = 2.2) person-days of data, with 2187 non-missing EMA assessments (2605 total were instructed). Complete data were provided for an average of 81.0 % of signaled random prompts (SD = 0.12, range 60.4–99.4 %), which took an average of 1.5 min (SD = 1.1, range 0.4–13.9) to finish. Participants also completed 93.1 % of all morning assessments (SD = 0.08, range 78.6–100 %), which took an average of 1.2 min (SD = 1.2, range 0.2–6.3) to finish. However, while complete data were provided for 162 drinking/drug use episode start assessments, participants initiated this assessment only 64.1 % of the time when they reported having drank that day on the morning assessment (the next day). Drinking/drug use episode assessments took an average of 2.3 min (SD = 1.9, range 0.4–13.3). Figure 1 provides a plot of the number of missed morning assessments (Panel 1), drinking/drug use assessments missed (Panel 2), and the mean percentage of random prompts missed (Panel 3) by study day. Lowess curves show that the pattern of missed assessments was relatively stable across the study period, regardless of assessment type.

Fig. 1.

Count of the number of missed morning assessments (daily diary), number of drinking/drug use assessments missed, and percentage of random prompts missed, by study day

Participants provided 619 complete assessments after they reported beginning to drink on a given day (either via random prompt or the drinking/drug episode assessment, whichever came first). In a GEE model of participants’ response rates to random prompts (normal distribution, identity link), completion rates did not differ for assessments collected after participants began drinking versus when they had not (b = 3.00, SE = 2.38, p = 0.208; not drinking: M = 82.6 %, SD = 24.9; after drinking: M = 83.2 %, SD = 21.5). In a model exploring whether response rates varied by how much participants drank on a given day (where 0 = no drinking, 1 = 1–4 drinks, and 2 = 5+ drinks that day), the percentage of random prompts completed was not lower on drinking or heavy drinking days compared with days on which participants did not drink (b = 0.03, SE = 0.03, p = 0.252). In a similar GEE model predicting the odds of failing to initiate drinking/drug use assessments on a day when drinking was reported (binomial distribution, logit link), alcohol use level was associated with a reduced odds of missing these assessments (OR 0.38, SE = 0.13, p = 0.005). These results suggest that response rates were likely not affected by drinking and/or intoxication and that reasons other than heavy drinking are likely responsible for poor response rates to event-contingent assessments.

Reactivity

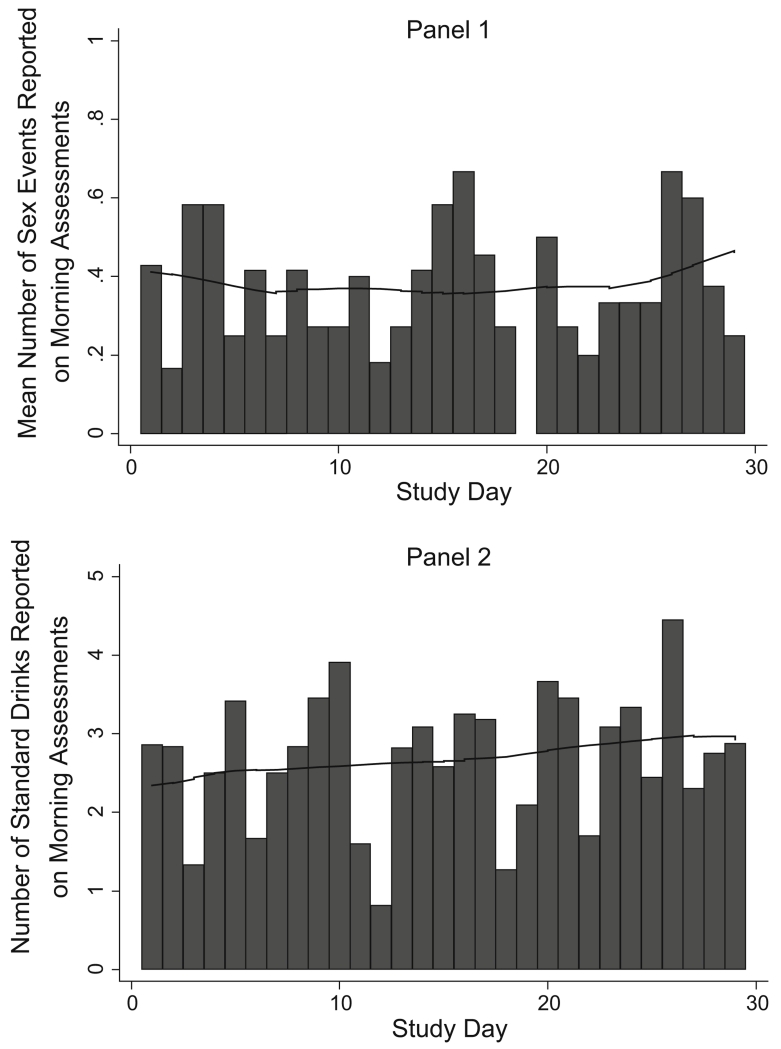

During the 30-day EMA procedure, participants reported a total of 112 sex events on the morning assessment. Characteristics of these sex events are reported in Table 1, and suggest that a substantial number of sexual risk events were captured during the 30-day assessment period. Figure 2 provides plots of the number of sex events and drinks per day reported by study day. Lowess curves similarly show no significant change in the number of these behaviors that were reported across the study period.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sexual events reported via morning assessments

| Characteristics of sex partners/events | % of events | Characteristics of sex partners/events | % of events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partner gender | Where met | ||

| Male | 94.7 | Online | 80.8 |

| Female | 4.3 | At a party | 11.6 |

| Partner type | HIV Status a | ||

| Casual | 84.2 | HIV-negative | 57.4 |

| Regular/steady | 15.8 | HIV status unknown | 42.6 |

| Length known | Events involving insertive anal b | 36.1 | |

| “Just met” | 49.4 | Condom unprotected | 64.1 |

| <1 month | 14.8 | Events involving receptive anal b | 26.9 |

| >1 month | 35.8 | Condom unprotected | 89.7 |

Categories listed for all variables do not reflect all possible response options, only those that were commonly selected

Represents the perceived HIV-statuses of all anal sex partners as self-reported by participants. No sex events with HIV-positive partners were reported

Represents the number of sex events involving this act (of all reported sex events with men)

Fig. 2.

Number of reported sex events and drinks per day by study day

Next, we examined whether there was evidence that reports of sensitive behaviors (e.g., alcohol/drug use, sex) were systematically different during the EMA period compared with the 30-days before. T-tests comparing mean frequency of sex and drinking/drug use events reported in the baseline TLFB (30 days prior to enrollment) to the follow-up TLFB (30 days during the EMA period) found no differences in the mean number of sex events (M = 2.2, SD = 6.2 vs. M = 2.4, SD = 6.5), anal sex (M = 4.75, SD = 0.7 vs. M = 5.0, SD = 1.9), UAI (M = 3.5, SD = 0.7 vs. M = 4.8, SD = 1.9), heavy drinking (M = 3.7, SD = 2.3 vs. M = 6.1, SD = 3.5), and marijuana use days (M = 3.8, SD = 10.6 vs. M = 4.4, SD = 10.2). Together, these results do not provide strong evidence of reactivity during the assessment period, since behavior reports did not systematically change over the course of the study period. Behaviors reported on the TLFB also did not change appreciably during the EMA monitoring period compared with the 30 days before it began.

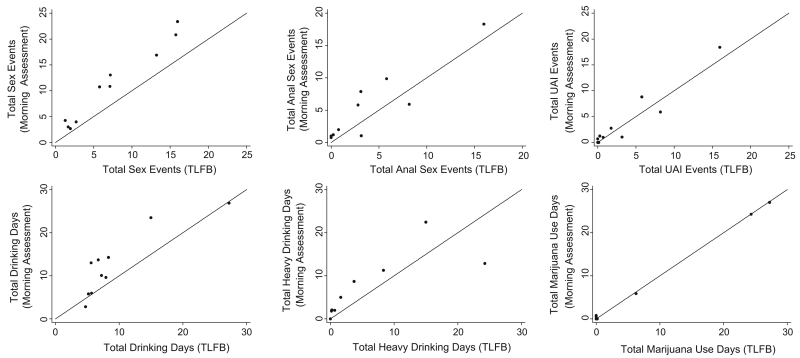

Comparing EMA (Daily Diary) and TLFB Reports

Participants provided complete data for all days assessed via follow-up TLFB. A total of 73 sex events were reported on the TLFB, 35 % less than in the EMA-morning assessment reports. Nevertheless, pairwise correlations between reports collected via EMA and TLFB for each participant’s total number of sex events, anal sex events, and UAI events were high (r = 0.91–0.96). Means of total “counts” of sexual and alcohol/drug use behaviors are provided in Table 2. Despite high overall correlations, mean comparisons suggest a pattern of possible underreporting in the TLFB, with approximately 2 fewer anal sex events reported in the TLFB compared to EMA and 1 fewer UAI event. Perhaps most concerning for the use of calendar-based retrospective recall methods is that only a few “high risk” sex events (UAI occurring with HIV-status unknown partners) were reported on the TLFB, but an average of 2 such events were reported per participant via the EMA procedure. Scatterplots of sex event counts depicted in Fig. 3 confirm a general pattern of possible underreporting on the TLFB. Most observations are concentrated above the reference line (which represents perfect agreement across the two methods), suggesting that a greater number of each event was reported via the EMA procedure.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of total alcohol/drug use and sexual behavior reported via EMA and TLFB over 30 days

| Variable | Morning assessment (daily diary) |

TLFB |

ra | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol/drug use | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Drinking days | 12.6 | 7.5 | 9.4 | 6.8 | 0.88 |

| Heavy drinking days | 6.6 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 8.1 | 0.81 |

| Marijuana use days | 5.8 | 10.6 | 5.7 | 10.6 | 0.98 |

| Sexual Behavior | |||||

| Anal sex days | 5.4 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 4.9 | 0.91 |

| UAI days | 4.0 | 5.7 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 0.96 |

| UAI w/casual partner days | 3.8 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 0.96 |

| High-risk sex daysb | 2 | 5.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.83 |

| Alcohol/drug use and sex | |||||

| Alcohol and sex daysc | 5.2 | 7.2 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 0.96 |

| Alcohol/drug involved sex daysd | 4.8 | 6.8 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 0.94 |

All values are p < 0.05

“High risk sex” = UAI with an HIV+ or status unknown partner

Days on which participants reported any drinking and any sex

Days on which participants specifically reported having sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs

Fig. 3.

Inter-method agreement between EMA and TLFB assessment of total events, 30 days. These figures depict the total number of any sex, anal sex, and UAI events, as well as the total number of drinking days, heavy drinking (5+) days, and marijuana use days, with EMA (daily diary) reports on the y-axis and TLFB (recall) data on the x axis. The trend line reflects perfect agreement

Table 3 shows agreement across the two methods about the occurrence of various events on specific days. Here, ICC values reflect poor agreement between the two measures across most of the behaviors assessed, suggesting that participants often failed to accurately recall the correct day on which these behaviors occurred. Table 4 shows the frequency with which reports of all sexual behaviors that occurred (e.g., oral and/or insertive anal and/or receptive anal) and critical partner characteristics (e.g., HIV-status, new partners) were correctly matched across the two methods in terms of their occurring on the same day (“correct match”), an adjacent day (1 day before/after, “near miss”) or were discrepant or reported ≥2 days apart (“miss”). Only 14 % of sex events were correctly matched in terms of which behaviors occurred on specific days, and only 7 % of partners were correctly matched in terms of their characteristics on specific days. These findings support the use intensive longitudinal designs to more accurately capture behaviors and their timing.

Table 3.

Absolute agreement about behavioral and partner characteristics of sex events reported on specific days across EMA (morning assessments) and TLFB

| Variable | Agreement (%) | ICCa |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual behaviors | ||

| Any sex | 72.9 | 0.27 |

| Oral sexb | 35.5 | 0.11 |

| Anal sexb | 56.4 | 0.19 |

| Unprotected anal sexb | 65.5 | 0.35 |

| Alcohol/drug use involved sexb | 60.9 | 0.28 |

| Partner characteristics | ||

| Number of partners (on a given day) | 69.4 | 0.55 |

| New partnerc | 49.1 | 0.35 |

| HIV statusc | 67.9 | 0.52 |

Intra-class correlation, calculated using either mixed effects probit (for binary response) and linear (for continuous response) models

Reflects agreement about sex acts that occurred on days when sex was reported via either method

Days were coded 1 if any of the (up to 4) partners were “new” or “HIV-status unknown,” with 0 reflecting only known or HIV-negative partners for a given day

Table 4.

Percentage of “matching” sex events comparing each day of EMA and TLFB reports

| Variable | Sexual behaviora | Partner characteristicsb |

|---|---|---|

| Exact match | 13.9 | 7.4 |

| Near miss | 20.9 | 13.8 |

| Miss | 65.2 | 78.7 |

Reflects match between all sexual behaviors (oral and/or insertive anal and/or receptive anal)

Reflects match between all partner characteristics (number of partners, their HIV-status(es), and whether they were new)

Discussion

Acceptability and Feasibility

Overall, the results of this small study show that conducting EMA research with very high-risk MSM is acceptable and feasible. Response rates to both experience sampling (random prompts) and daily diary (morning) assessments met or nearly met their target rates, and exceeded the completion rates of many past daily diary studies with MSM, which range from 78–83.7 % [22, 26,48, 49]. Several factors could explain the higher response rates in our study. All past daily diary studies of MSM collected diaries online, which typically involve sending participants a link to the online survey each day via email. While some participants in these studies may have completed daily surveys on mobile devices, some may have accessed surveys primarily via desktop/laptop computers. In contrast, our study utilized a native Android application to conduct the EMA procedure, so all surveys were completed via smartphone. Thus, it could be that allowing participants to complete assessments while going about their daily lives boosted adherence. Native smartphone applications also have advantages in terms of signaling. In online daily diary studies, even if participants access web surveys using their smartphone, prompting participants to respond via email often uses the same notification cues (e.g., ring tone, “lock screen” messages, etc.) as other processes, which can blend in with unimportant information (e.g., spam email) or get lost. Native smartphone applications can manipulate the smartphone’s settings (e.g., speaker volume, vibration, notification displays) and temporarily lock other processes to ensure that prompts are addressed. Thus, collecting EMA data via smartphone may have advantages that allow participants mobility and benefit their adherence to study procedures.

While adherence to daily diary and experience sampling assessments was high, rates of responding to event-contingent assessments was relatively poor. Participants were asked to complete these assessments whenever they began using alcohol or drugs on a given day. If they forgot, they were asked to initiate the assessment as soon as they remembered, and this was complimented by reminders in random prompts to complete drinking/drug use episode assessment if they reported drinking since the last prompt. Some past studies have reported similar difficulty with comparatively poor response rates for event-contingent assessments of substance use [50, 51]. This problem could be due to barriers to incentivizing these assessments. While other EMA components (daily diary, experience sampling) are typically incentivized so that payment is determined by response rates, taking a similar approach to incentivizing event-contingent assessments of substance use behavior would clearly be problematic. It could reinforce drinking/drug use itself or participants may attempt to boost their compensation by frivolously recording daily drinking episodes. One way to address this problem in future research might involve scheduling event-specific assessments to be sent automatically after participants indicate current drinking in a random prompt. This way, event-contingent assessments could be compensated like any other random assessment (i.e., with bonuses reflecting a high percentage of prompts completed). Additionally, participants would not be required to remember to initiate a prompt on their own when they start drinking, and instead would be notified by alarms and vibration in the same way as random prompts.

Several participant orientation, training, and management procedures also likely contributed to high overall adherence rates. These include: (1) building rapport, (2) emphasizing the importance of the study’s data (while being realistic about its intensity), (3) providing regular feedback about response rates, (4) providing ongoing troubleshooting of barriers to adherence, and (5) incentivizing adherence. Building rapport generally involved our staff devoting time to making friendly conversation with participants and finding common ground with them before initiating research procedures. Staff were also realistic about the difficulties involved with the research [34], such as being interrupted several times throughout the day often at inopportune times (e.g., during work). Participants received weekly emails and messages through the smartphone’s software that provided them with their response rates to random and morning assessments over the last week and overall, as well as reminders of the targets for each assessment type. If participants fell below 80 % of random prompts or missed >2 days of morning assessments, staff called them to ask about any obstacles they had in responding. Throughout the study, staff discussed various strategies participants might use to help overcome obstacles in responding and improve their response rates. Finally, we compensated participants according to their response rates, so as to incentivize adherence. A large portion of this payment consisted of “bonuses” for achieving target response rates during a given period, which may have provided motivation for consistent responding.

One concern about EMA research on alcohol use is the potential that response rates will be affected by intoxication. Our findings show that participants’ response rates to EMA prompts (both experience sampling and event-contingent assessments) do not decline either on days when they drank or after they have begun drinking on a given day. Past studies have used EMA to explore the subjective effects of intoxication, and show that those effects reported via EMA generally mirror those reported in more controlled laboratory studies [52–55]. Together, these findings suggest that concerns about poor response rates or haphazard responding by intoxicated participants in EMA studies are likely unfounded.

Reactivity

In general, we did not find clear evidence of reactivity in our study. Reports of sex and drinking/drug events, as well as adherence to the EMA procedure overall, did not change systematically across the 30 day study period. Moreover, participants did not report a significantly different number of sex and drinking/drug events on a TLFB of the 30 days before enrolling compared to a TLFB of the 30 days during EMA.

Agreement Between EMA Reports and Follow-Up TLFB

We also compared the consistency of participants’ reports of sexual behavior and alcohol/drug use when provided the day after they occurred (EMA) versus 30 days later (TLFB). Results suggested that total reports of most sexual behaviors and alcohol use were comparable across both methods, but that participants may have under reported these events on the TLFB compared to EMA. One exception was total marijuana use days, which appeared to be consistent across methods. However, agreement between reports of these behaviors occurring on specific days was poor overall. While participants’ reports across the two assessments often agreed that some sex occurred on a given day, the two reports were often discrepant in terms of what kind sex acts occurred, whether they involved condom use, and whether they were under the influence of alcohol/drugs. Participants’ reports of characteristics of their partners fared similarly. Examining whether participants reported events essentially around the same time but were off by ± a day, findings suggested that most reports disagreed about some act or were discrepant about when they occurred by more than one day. Worse “matching” was observed with respect to characteristics of partners (casual/regular, HIV-status, and new partner), with only 21 % agreeing about these characteristics on a given day or an adjacent day (±). Overall, these findings suggest that assessing sexual behavior soon after it occurs may be more accurate than recall methods among this high-risk group, even when the recall period is relatively short (30 days). One explanation for this discrepancy, however, might be the characteristics of this high-risk sample. Since most participants reported a high number of partners, this may render the specific characteristics of each partner and/or timing of events more difficult to recall after 30 days. While daily recall methods (like TLFB) may be sufficient when total involvement in risk over a given period is of interest, researchers exploring hypotheses about other factors involved in HIV-risk events should use methods that reduce the potential for recall errors when possible (e.g., daily, weekly diaries), since these questions depend on participants’ ability to correctly report both behaviors and the time at which they occurred (i.e., on the correct day). For example, studies examining whether alcohol and/or drug use co-occurs with HIV-risk behavior on the same day might achieve more reliable results using an assessment strategy that enables more accurate recall of when drinking/drug use occurs relative to risk. Using these “proximal” assessment methods is more feasible for applied researchers today than ever before, since innovations in technology over the last few decades have made them more accessible and affordable. A variety of software systems are now available that could be used to facilitate frequent assessment via technologies that most populations already use. For example, many internet-based survey software systems can be customized to deliver daily diary surveys, and a number of stock smartphone applications designed for experience sampling can be used to facilitate daily (or more frequent) assessments.

Limitations

A number of limitations of this study are important to note. First, the data reported in this study were from a small feasibility study involving only 12 participants (334 days, 112 sex events, and 159 drinking events). As such, larger samples may allow more confident conclusions about these results. Second, participants enrolled in this study were recruited from a single source: A popular smartphone application used by gay men to meet partners. Thus, these findings could uniquely apply to MSM who use this application. Finally, TLFBs were collected online during participants’ in-person visits to facilitate comparisons between reports of sex and alcohol/drug use behavior reported via recall (up to 30 days) versus daily assessment. It is possible that the under-reporting and sub-optimal matching rates observed between these assessment methods would have been improved had the TLFB been delivered in a different way (e.g., interview).

Conclusions

Intensive longitudinal methods may provide more accurate data on HIV-risk and associated behaviors like alcohol and drug use. However, these methods also provide a critical opportunity to improve our understanding of participants’ social, environmental, and psychological context around the time HIV-risk events occur in the real world. Studying these factors is difficult, since it depends on validly assessing constructs that can be difficult or impossible to recall at a later time. For example, many factors involved in sexual decision-making, such as motives for having sex, risk perceptions, perceived control over use of protection, and so on, are likely only validly measured around the time that sex events occur. For this reason, studies of sexual decision-making have largely been relegated to experimental research designs that typically assess these factors in the context of hypothetical sexual scenarios and rely on assessments of sex and protection intentions rather than actual behavior [56–59]. Well-designed research using proximal assessment methods (e.g., daily diary, EMA) can provide an important opportunity to understand how sexual decisions are made and how different contexts affect these choices in the real world.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants T32AA007 459, P01AA019072, and L30AA023336.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, Goodreau SM, Chariyalertsak S, Wirtz AL, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):367–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, Rosen DH, McFarland W, Shehan DA, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2000;284(2):198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koblin BA, Chesney MA, Husnik MJ, Bozeman S, Celum CL, Buchbinder S, et al. High-risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in 6 US cities: baseline data from the EXPLORE Study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):926–32. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Humberstone M, Walavalkar I, Chiasson MA. Substance use and high-risk sex among men who have sex with men: a national online study in the USA. AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):1036–47. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce D, Kahana S, Harper GW, Fernández MI, ATN Alcohol use predicts sexual risk behavior with HIV-negative or partners of unknown status among young HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2013;25(5):559–65. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.720363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorin AA, Stone AA. Recall biases and cognitive errors in retrospective self-reports: a call for momentary assessments. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Vol. 23. Erlbaum; Mahwah: 2001. pp. 405–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobell L, Sobell M. Timeline followback user’s guide: a calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back. Measuring alcohol consumption. Springer; Totowa: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Johnson ME. HIV risk behavior self-report reliability at different recall periods. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):152–61. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wray TB, Braciszewski JM, Zywiak WH, Stout RL. Examining the reliability of alcohol/drug use and HIV-risk behaviors using Timeline Follow-Back in a pilot sample. J Subst Use. 2015 doi: 10.3109/14659891.2015.1018974. doi:10.3109/14659891.2015.1018974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinhardt LS, Forsyth AD, Carey MP, Jaworski BC, Durant LE. Reliability and validity of self-report measures of HIV-related sexual behavior: progress since 1990 and recommendations for research and practice. Arch Sex Behav. 1998;27(2):155–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1018682530519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey MP, Carey K, Maisto S, Gordon C, Weinhardt L. Assessing sexual risk behaviour with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(6):365–75. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidovich U, de Wit JB, Stroebe W. Assessing sexual risk behaviour of young gay men in primary relationships: the incorporation of negotiated safety and negotiated safety compliance. AIDS. 2000;14(6):701–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200004140-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prestage G, Mao L, McGuigan D, Crawford J, Kippax S, Kaldor J, et al. HIV risk and communication between regular partners in a cohort of HIV-negative gay men. AIDS Care. 2006;18(2):166–72. doi: 10.1080/09540120500358951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortenberry JD, Temkit MH, Tu W, Graham CA, Katz BP, Orr DP. Daily mood, partner support, sexual interest, and sexual activity among adolescent women. Health Psychol. 2005;24(3):252. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey SL, Gao W, Clark DB. Diary study of substance use and unsafe sex among adolescents with substance use disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(3):297, e13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiene SM, Barta WD, Tennen H, Armeli S. Alcohol, helping young adults to have unprotected sex with casual partners: findings from a daily diary study of alcohol use and sexual behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroder KE, Johnson CJ, Wiebe JS. An event-level analysis of condom use as a function of mood, alcohol use, and safer sex negotiations. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38(2):283–9. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Ventuneac A, Mustanski B. Accuracy of highly sexually active gay and bisexual men’s predictions of their daily likelihood of anal sex and its relevance for intermittent event-driven HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(4):449–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mustanski BS. The relationship between mood and sexual interest, behavior, and risk-taking: ProQuest Information & Learning. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herbenick D, Reece M, Hensel D, Sanders S, Jozkowski K, Fortenberry JD. Association of lubricant use with women’s sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and genital symptoms: a prospective daily diary study. J Sex Med. 2011;8(1):202–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick ME, Maggs JL. Does drinking lead to sex? Daily alcohol—sex behaviors and expectancies among college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(3):472. doi: 10.1037/a0016097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grov C, Golub SA, Mustanski B, Parsons JT. Sexual compulsivity, state affect, and sexual risk behavior in a daily diary study of gay and bisexual men. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(3):487. doi: 10.1037/a0020527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvath KJ, Beadnell B, Bowen AM. A daily web diary of the sexual experiences of men who have sex with men: comparisons with a retrospective recall survey. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(4):537–48. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Diaries for observation or intervention of health behaviors: factors that predict reactivity in a sexual diary study of men who have sex with men. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47(3):325–34. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9549-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith A. Smartphone ownership—2013 update. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tennen H, Affleck G, Coyne JC, Larsen RJ, DeLongis A. Paper and plastic in daily diary research: Comment on Green, Rafaeli, Bolger, Shrout, and Reis (2006) 2006 doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swendeman D, Comulada WS, Ramanathan N, Lazar M, Estrin D. Reliability and validity of daily self-monitoring by smartphone application for health-related quality-of-life, antiretroviral adherence, substance use, and sexual behaviors among people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):330–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0923-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradburn NM, Rips LJ, Shevell SK. Answering autobiographical questions: the impact of memory and inference on surveys. Science. 1987;236(4798):157–61. doi: 10.1126/science.3563494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wray TB, Merrill JE, Monti PM. Using Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) to assess situation-level predictors of alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2015;36(1):19–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson RO. Assessment and therapeutic functions of self-monitoring. In: Hersen M, Eisler RM, Miller PM, editors. Progress in behavior modification. Vol. 4. Academic Press; New York: 1977. pp. 263–308. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol Assess. 2009;21(4):486. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiffman S. Designing protocols for ecological momentary assessment. In: Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza A, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture: self-reports in health research. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. pp. 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175(9):526–36. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahler CW, Wray TB, Pantalone DW, Kruis RD, Mastroleo NR, Monti PM, et al. Daily associations between alcohol use and unprotected anal sex among heavy drinking HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:422–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0896-7. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0896-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sander PM, Cole SR, Stall RD, Jacobson LP, Eron JJ, Napravnik S, et al. Joint effects of alcohol consumption and high-risk sexual behavior on HIV seroconversion among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2013;27(5):815–23. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cff4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vosburgh HW, Mansergh G, Sullivan PS, Purcell DW. A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1394–410. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang C, Linas B, Kirk G, Bollinger R, Chang L, Chander G, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment of alcohol use among African American men who have sex with men in Baltimore. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015;3(2):e67. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, Day AM. Ecological momentary assessment of acute alcohol use disorder symptoms: associations with mood, motives, and use on planned drinking days. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22(4):285. doi: 10.1037/a0037157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addict Behav. 2010;35(12):1045–53. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Gwaltney CJ, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, et al. Prediction of lapse from associations between smoking and situational antecedents assessed by ecological momentary assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(2):159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiffman S. How many cigarettes did you smoke? Assessing cigarette consumption by global report, Time-Line Follow-Back, and ecological momentary assessment. Health Psychol. 2009;28(5):519–26. doi: 10.1037/a0015197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. STATA press; College Station: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mustanski B. Moderating effects of age on the alcohol and sexual risk taking association: an online daily diary study of men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):118–26. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Ventuneac A, Mustanski B. Accuracy of highly sexually active gay and bisexual men’s predictions of their daily likelihood of anal sex and its relevance for intermittent event-driven HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. JAIDS. 2015;68(4):449–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Litt MD, Cooney NL, Morse P. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) with treated alcoholics: methodological problems and potential solutions. Health Psychol. 1998;17(1):48. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collins RL, Kashdan TB, Gollnisch G. The feasibility of using cellular phones to collect ecological momentary assessment data: application to alcohol consumption. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;11(1):73. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miranda R, Jr, MacKillop J, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Tidey J, Gwaltney C, et al. Effects of topiramate on urge to drink and the subjective effects of alcohol: a preliminary laboratory study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(3):489–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piasecki TM, Wood PK, Shiffman S, Sher KJ, Heath AC. Responses to alcohol and cigarette use during ecologically assessed drinking episodes. Psychopharmacology. 2012;223(3):331–44. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2721-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ray LA, Miranda R, Jr, Tidey JW, McGeary JE, MacKillop J, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Polymorphisms of the l-opioid receptor and dopamine D4 receptor genes and subjective responses to alcohol in the natural environment. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119(1):115. doi: 10.1037/a0017550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tidey JW, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Gwaltney CJ, Miranda R, McGeary JE, et al. Moderators of naltrexone’s effects on drinking, urge, and alcohol effects in non-treatment-seeking heavy drinkers in the natural environment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(1):58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maisto SA, Palfai T, Vanable PA, Heath J, Woolf-King SE. The effects of alcohol and sexual arousal on determinants of sexual risk in men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(4):971–86. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9846-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wray TB, Simons JS, Maisto SA. Effects of alcohol intoxication and autonomic arousal on delay discounting and risky sex in young adult heterosexual men. Addict Behav. 2015;42:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis KC, Hendershot CS, George WH, Norris J, Heiman JR. Alcohol’s effects on sexual decision making: an integration of alcohol myopia and individual differences. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(6):843–51. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davis KC, Norris J, Hessler DM, Zawacki T, Morrison DM, George WH. College women’s sexual decision making: cognitive mediation of alcohol expectancy effects. J Am Coll Health. 2010;58(5):481–9. doi: 10.1080/07448481003599112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]