Abstract

This study examined whether Mexican-American parent’s experiences with discrimination are related to adolescent psychological adjustment over time. The extent to which associations between parent discrimination and adolescent adjustment vary as a function of parent’s ethnic socialization of their children was also examined. Participants included 344 high school students from Mexican or Mexican-American backgrounds (primarily second generation; ages 14 – 16 at Wave 1) and their primary caregivers who completed surveys in a two-year longitudinal study. Results revealed that parent discrimination predicted internalizing symptoms and self-esteem among adolescents, one year later. Additionally, adolescents were more likely to report low self-esteem in relation to parents’ increased experiences of discrimination when parents conveyed ethnic socialization messages to them.

Keywords: discrimination, adolescence, psychological adjustment, Mexican-American, ethnic socialization

Discrimination experiences are a significant threat to the healthy development of ethnic minority youth. Studies have demonstrated that Mexican-American adolescents’ experiences with ethnic discrimination are related to their psychological adjustment, including internalizing and externalizing problems (e.g., Berkel et al., 2010; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). Despite the critical role that parents play in the lives of Mexican-American youth (Kuperminc, Wilkins, Jurkovic, & Perilla, 2013), to our knowledge no studies have extended beyond studying adolescents’ own experiences and related outcomes to examine whether Mexican-American adolescents are also impacted by discrimination experienced by their parents. Support for the hypothesis that parents’ discrimination incidents are related to youth adjustment has been found in studies with African American and Chinese families (e.g., Benner & Kim, 2009; Ford, Hurd, Jager, & Sellers, 2013). The current study extends this limited research by examining whether Mexican-American parent’s experiences with discrimination are related to adolescent psychological adjustment, one year later. Based on their experiences with discrimination, it may be expected that parents will convey certain messages or concerns about cultural acceptance and hostility to their adolescents. Thus, the current study also examines whether ethnic socialization messages amplify or attenuate links between parent discrimination and adolescent adjustment.

Linking Parent Discrimination Experiences to Adolescent Adjustment

Despite the growing literature on adolescent’s individual reactions to discrimination, only a few studies have examined whether adolescents are impacted by their parents’ discrimination. The integrative model for minority youth (García-Coll et al., 1996) emphasizes the central role of discrimination in shaping adjustment outcomes for ethnic minority youth. It also helps explain why parents’ experiences with discrimination may influence adolescents’ development. As the model suggests, discrimination is a critical social mechanism by which culturally relevant factors (e.g., acculturation; Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2013) and family processes (e.g., familismo; Berkel et al., 2010) may alter adolescent outcomes. For example, Mexican-American adolescents who faced discrimination incidents and also endorsed more Mexican-American values such as familism showed mental health improvements. Thus, it may be expected that parents’ discrimination experiences are related to adolescent development and the nature of that link could depend upon ethnic socialization practices in the family (García-Coll et al., 1996). Furthermore, consistent with an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1989), the examination of caregiver discrimination experiences in conjunction with the proximal contextual factor of caregiver-adolescent discussions on topics of race and prejudice may show how such experiences differently impact adolescent psychological outcomes. That is, the current study focuses on individual and environmental characteristics to inform our understanding of adolescent adjustment in relation to caregiver discrimination. Overall, the limited studies in the area find that parent discrimination is related to negative adjustment among their children, but only during late childhood and adolescence. Caughy, O’Campo and Muntaner (2004) found no differences in African-American preschool children’s behavior problems based on parent discrimination. However, in a study of African-American parents and their late elementary school-aged children, parent reports of discrimination were concurrently associated with children’s distress levels (Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004). This finding supports the notion that awareness of discrimination incidents among a member of one’s ethnic group, especially a parent, is disconcerting to youth. Moreover, the older age of the youth in Gibbons et al. (2004) is likely important because with increasing age and cognitive development, youth have greater capacity to interpret the meaning of parents’ discrimination experiences and its relevance in their own lives.

To our knowledge, two studies have examined these relationships among adolescents. Ford and colleagues (2013) longitudinally examined the experiences of African American caregivers and adolescent dyads and found that caregivers’ experiences with discrimination were related to increases in depressive symptoms and declines in well-being among adolescents. Therefore, although it was not known whether adolescents personally witnessed their parents’ discrimination, these experiences may have left them more vulnerable to maladjustment. The findings support the stress model of discrimination, which posits that experiences with perceived discrimination result in psychological or physiological stress (e.g., Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999). Thus, after a parent experiences an act of discrimination they are likely to react with a stress response (e.g., maladaptive coping) which may directly or indirectly impact the teen. In the second study, the researchers focused on how parents’ discrimination experiences were related to Chinese American adolescents’ ethnicity-related stressors (e.g., sense of cultural misfit, attitudes toward education; Benner & Kim, 2009). Results showed support for mediation models in which parent discrimination was related to greater ethnic socialization practices (i.e., racial bias preparation). These socialization practices in turn, were related to a stronger sense of cultural misfit among adolescents. The authors conclude that messages about preparation for racial bias, stemming from parents experiences with discrimination, lead adolescents to feel more stigmatized in U.S. culture. Although ethnic socialization was also tested as a moderator, there was no support for these models. Benner and Kim (2009) note that this may reflect the transactional nature of intergenerational discrimination experiences and that because Asian American parents rarely discuss discrimination with their children (Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006), these experiences may only be indirectly related to adolescent’s well-being. Taken together, these findings indicate that parents’ personal experiences and the messages they convey about these experiences may both be important predictors of adolescents’ self concept and mental health. However, Benner and Kim’s (2009) findings with Asian American youth also raise the possibility that ethnic socialization practices such as racial bias preparation may not produce expected benefits when they occur in the context of parents’ discrimination experiences. Since this finding stands in contrast to research that posits racial socialization is a protective resource for minority populations (Hughes et al., 2006), additional research is warranted to better tease out such nuances and to examine linkages among parent’s discrimination, racial socialization, and adolescent well-being with other populations.

In the current study of Mexican-American youth, parents’ discrimination experiences were examined as predictors of adolescent psychological adjustment. We also examined whether these associations varied as a function of their parents’ ethnic socialization practices. In contrast to Benner and Kim (2009) who found support for ethnic socialization as a mediator, we examined ethnic socialization as a moderator for two reasons. First, we hypothesized that parents’ socialization practices related to discrimination may function to support Mexican American youths’ understanding and adaptation to their parents’ experiences, and thus, may not just be reactive but also serve an adaptive function in parent-child dynamics related to discrimination. Second, although parents’ ethnic socialization or preparation for bias may be contingent on the extent to which they have experienced discrimination in their own lives, our longitudinal data with two time points did not allow us to test mediation. Thus, the tenets of the integrative model framework (Garcia Coll et al., 1996) are further investigated in this study by examining the extent to which the magnitude of the association between parent discrimination and adolescent adjustment depends on ethnic socialization.

The Role of Ethnic Socialization

Parents’ discussion of topics related to ethnicity and race with their children is recognized as a salient component of parenting among ethnic minority families (Hughes et al., 2006; Priest et al., 2014). Within the context of discrimination experiences, ethnic socialization practices are often discussed as protective (e.g., Neblett, White, Ford, Nguyên, & Sellers, 2008). In particular, cultural socialization (teaching about ethnic heritage and history) may be protective against the detrimental effects of discrimination as it promotes positive views about one’s ethnic group even in the face of discriminatory acts. However, discussions about preparation for bias and the promotion of mistrust, signaling to youth that they may face prejudice and discrimination because of their ethnic background or that they should be cautious with certain groups, have been found to be both protective and harmful (Evans, Banerjee, Meyer, Aldana, Foust, & Rowley, 2012). That is, these messages may protect youth from the negative outcomes associated with discrimination because it prepares them to cope and allows them to attribute discrimination to others prejudice (e.g., Neblett et al., 2008). However, preparation for bias also has been found to amplify the negative relation between adolescent discrimination and self-esteem (Harris-Britt, Valrie, Kurtz-Costes, & Rowley, 2007). Due to prior mixed findings and because these studies have not examined the link between parents’ discrimination and adolescent psychological adjustment among Mexican-Americans, we examined the protective versus risk-amplifying effects of parents’ ethnic socialization as competing hypotheses.

Current Study

Adolescence is a prime developmental period to study discrimination and ethnic socialization practices. During adolescence, parents are more likely to discuss topics of race and ethnicity as teens are more cognitively and emotionally prepared to understand these issues (Hughes & Chen, 1997; Lalonde, Jones, & Stroink, 2008). Examining the links between parents’ experiences with discrimination and the well-being of their adolescent children and investigating the processes that may help explain these associations is an area ripe for inquiry (Benner & Kim, 2009). Additionally, the fact that most discrimination and ethnic socialization studies have focused on the experiences of African American families has been noted as a limitation in the field (Hughes et al., 2006). The current study extends past research to test these associations among Mexican-American families. The experiences of Mexican-American families are important to study not only because they remain an understudied group in discrimination research, but also because Mexican-Americans are one of the largest ethnic minority groups in the United States who are identified as being at higher risk for psychological adjustment outcomes compared to youth from other ethnic backgrounds (Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003). Given the emphasis on closeness and respect for family members among Mexican-Americans (Kuperminc et al., 2013), it may be particularly important to understand the extent to which parent discrimination relates to their adolescent’s well-being and the extent to which ethnic socialization amplifies or attenuates such links.

García-Coll’s integrative model specifies that personal experiences with discrimination may be frequent and normative among ethnic minority youth (García-Coll et al., 1996). Thus, adolescent reports of discrimination were included as a control in the models. Furthermore, it is possible that parents’ cultural socialization, preparation for bias or promotion of mistrust might also occur in response to adolescents’ discrimination experiences which may drive associations over time between these predictors and adolescent’s psychological adjustment. Thus, by including adolescent discrimination in the models, we better isolate the unique contribution of parent’s experiences and account for adolescents’ personal experiences with discrimination that likely also shape their adjustment. In sum, the current study is guided by two central aims. The first research aim is to examine whether Mexican-American parents experiences with discrimination are related to adolescent reports of psychological adjustment, one year later. The second research aim is to test if associations between parent discrimination and adolescent adjustment vary as a function of the parent’s ethnic socialization.

Method

Participants

Adolescents from Mexican backgrounds and their primary caregivers were recruited from two public high schools in Los Angeles (in the 2009–2010 academic year) to participate in a two-wave longitudinal study. In the first school, Latinos comprised 62% of the student body and 73% of students were eligible for free or reduced lunch. The second school consisted of mostly Latino (94%) students and 71% of students were eligible for free or reduced lunch.

Students from Mexican backgrounds enrolled in the ninth or tenth grade were invited to participate, along with their primary caregiver (i.e., family member who self-identified as the adult who spent the most time with the adolescent and knew the most about them). Among those students who were invited to participate and were eligible, 63% agreed to participate. This rate compares favorably with past intensive studies (e.g., home interview followed by daily reports) among Latino families (e.g., Updegraff et al., 2005). At Wave 1, participants included 428 adolescents (Mage = 15.02, SDage = 0.83) from Mexican or Mexican-American backgrounds and their primary caregiver. One year later, a total of 344 (80%) of the families participated in Wave 2. Independent t-tests were run to compare participants who completed both waves of data to those who only participated in the first wave. Across the main study variables (e.g., parent discrimination, adolescent psychological adjustment) only one significant difference emerged. Adolescents who participated in Wave 1, reported higher levels of promotion of mistrust compared to participants who participated in both waves, t(417) = −3.261, p = .001.

The analytic sample for the current study includes the 344 families who participated during both waves. The adolescent sample was evenly split by gender (50% male). Seventy-one percent of students were second-generation (i.e., they were born in the United States (U.S.), but at least one of their parents was born outside of the U.S.), 11% were first-generation immigrants (i.e., they and their parents were born outside the U.S.), and 18% were third generation or later (i.e., they and both of their parents were born in the U.S.). The primary caregivers were largely participants’ mothers (85%) and the remaining were either participants’ fathers or other caregivers. In total, 96% of the caregivers were either the mother or father of the adolescent; for the sake of ease, we will refer to the primary caregivers as parents. Parent educational levels included less than a high school diploma (65%), high school graduate (8%) and at least some college attendance (27%).

Procedures

Letters were sent home to the families describing the study in English and Spanish. Graduate students visited classrooms to describe the study and answer questions. Researchers then made calls to parents to further describe the study and eligibility requirements. If the adolescent and primary caregiver agreed to participate, a meeting was set up to complete the consent and assent process in-person and complete questionnaires (predominately occurring in the family home). Questionnaires were completed by parents as an interview with a research team member and adolescents completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire independently. At each wave, adolescents were paid $30 for their participation and parents were paid $50.

Measures

Reports of discrimination experiences were drawn from the parent and adolescent questionnaire. The measures for ethnic socialization and psychological adjustment were drawn from the adolescent questionnaire. The following demographic information was obtained from the parent and adolescent questionnaires: gender, grade, generation status, school attended, whether mother was primary caregiver and parent education level (i.e., categories included: only elementary school completed, up to secondary school completed, or some college). These factors were included as controls in the main models.

Parent and adolescent discrimination (Wave 1)

A modified eight-item version of the Experiences with Discrimination Scale (Murry, Brown, Brody, Cutrona, & Simons, 2001) assessed parent and adolescent experiences with discrimination. Sample items included “How often has someone yelled a racial slur or racial insult at you” and “How often has someone ignored you or excluded you from some activity just because of your ethnic background”. Items were rated on a scale from (1) never to (4) several times, such that higher scores for the measure indicate more experiences with discrimination. The scale showed excellent reliability for adolescents (α = .87) and parents (α = .90).

Ethnic socialization (Wave 1)

Items from Hughes and Chen’s (1997) ethnic socialization scale were completed by adolescents. They reported the frequency of ethnic socialization messages that they received from their parents in the past year. Response options ranged from (1) never to (5) six or more times. The measure consisted of three subscales: cultural socialization (α = .80), preparation for bias (α = .80) and promotion of mistrust (α = .79). The three subscale correlations ranged from .17 to .40 and higher scores indicate greater ethnic socialization for each subscale.

Cultural socialization

This subscale consists of four items that assessed the extent to which parents encourage their children to learn more about their culture. For example, teens indicated how often their parents “Talked to you about important people or historical events of your ethnic group” and “Taken you to places or events that reflect your ethnic heritage.”

Preparation for bias

Six items assessed how often parents teach their adolescent children about ethnic discrimination. For example, adolescents were asked how often their parents “Talked to you about discrimination or prejudice against people of your ethnic group” and “Told you that people might try to limit you because of your ethnicity”.

Promotion of mistrust

The two items that assessed how often parents discourage their children from trusting people of other ethnic groups included: “How many times have your parents done or said things to keep you from trusting kids from other ethnic groups” and “…done or said things to keep your distance from kids of other ethnicities”.

Adolescent psychological adjustment (Wave 2)

Four indicators of adolescents’ psychological adjustment were assessed: internalizing problems, self-esteem, externalizing problems and substance use.

Internalizing problems

Adolescents completed the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991). The subscale is composed of 30 items rated on a scale with three response options: not true of me (0), somewhat or sometimes true of me (1), and true or often true of me (2). Thus, higher scores indicate more internalizing problems. Sample items included “I cry a lot” and “I feel overtired without good reason”. Alpha reliability in the current study was .87.

Self-Esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) assessed self-esteem. The scale consists of 10 items such as “I take a positive attitude towards myself” and “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”. Items are rated on a scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. The scale showed good reliability (α = .84).

Externalizing problems

Adolescents completed the externalizing behaviors subscale from the YSR (Achenbach, 1991). The subscale consisted of 32 items; adolescents were asked to rate how true each item was for them on the scale described for internalizing problems. Sample items include “I am mean to others” and “I get in many fights”. The scale had excellent reliability (α = .86).

Number of substances used

A measure adapted from the National 2001 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) assessed the number of substances adolescents have ever used in their lifetime. The scale accounts for the total number of substances used, including: cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, crystal meth, other illegal drugs (e.g., ecstasy,) and prescription drugs without a prescription. Higher scores indicate a greater number of substances used. Alpha reliability of this scale in the current study was .71.

Data Analytic Plan

The data analysis plan involved three steps to address the two research aims. First, to assess the percentage of Mexican-American parents and adolescents who reported discrimination incidents and the inter-correlations among the variables of interest, descriptive analyses were run. Second, to address the research aim that examines whether parents experiences with discrimination are related to adolescent reports of psychological adjustment, one year later, hierarchical regression models were tested. The models controlled for adolescent gender (dummy coded; male as the comparison group), grade (dummy coded; ninth grade as comparison group), generational status (dummy coded; first generation as comparison group), school and parent education level (dummy coded; only elementary school completed as comparison group) at the first step. These variables were included because they are key demographic variables and descriptive results showed that there were a few differences based on the psychological adjustment indicators that should be accounted for (e.g., differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms based on school). Models also controlled for adolescent’s reports of discrimination and the appropriate adolescent outcome at Wave 1. In the second step, the Wave 1 parent discrimination measure was entered. The adolescent discrimination and outcome control variables and the parent discrimination reports were centered to avoid multi-collinearity when interpreting the interactions from the final models (Fairchild & McQuillin, 2010).

Finally, three-level hierarchical regressions were run to test the research aim examining the extent to which associations between parent discrimination and adolescent adjustment were moderated by parent reports of ethnic socialization practices. The models described previously remained the same with the exception that a cross-product between discrimination and the ethnic socialization variable was included at the third step.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Overall, 72% of parents reported experiencing any discrimination incident (M = 1.70, SD = .72). There were no differences in parents’ reports of discrimination based on their generational status, F(2, 341) = 1.75, p = .18 or whether the primary caregiver was the mother or another family member, t(342) = −1.36, p = .17. Among adolescents, 75% reported experiencing any discrimination incident (M = 1.53, SD = .58). Parent reports of the frequency of discrimination experiences were higher than adolescent reports, t(339) = −3.51, p < .001.

Table 1 displays the intercorrelations among all of the key variables. Parent discrimination and adolescent discrimination were unrelated. The results indicated that as parent reports of discrimination increased, adolescent internalizing symptoms increased and self-esteem decreased. There was no association between parents’ discrimination experiences and adolescents’ externalizing problems or substance use. Adolescent discrimination was significantly associated with higher reports of internalizing and externalizing problems, but was not related with self-esteem or substance use. The three ethnic socialization indicators were inconsistently associated with the adolescent outcomes. Cultural socialization was related to lower internalizing symptoms and higher self-esteem. Preparation for bias was unrelated to adolescent adjustment, and promotion of mistrust was related to increased internalizing problems, lower self esteem, and increased externalizing problems.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations Among Parent and Adolescent Discrimination, Adolescent Adjustment and Ethnic Socialization

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent Discrimination | - | ||||||||

| 2. Adol. Discrimination | .06 | - | |||||||

| 3. Cultural Socialization | .03 | .22 | - | ||||||

| 4. Preparation for Bias | .10 | .46** | .40** | - | |||||

| 5. Promotion of Mistrust | .04 | .27** | .17** | .33** | - | ||||

| 6. Internalizing Problems | .17** | .15** | −14* | .09 | .14* | - | |||

| 7. Self-Esteem | −.14** | −.01 | .21** | .05 | −.12* | −.39* | - | ||

| 8. Externalizing Problems | .09 | .23** | −.09 | .07 | .23** | .52** | −.19* | - | |

| 9. Substance Use | .02 | −.09 | −.10 | −.09 | .04 | .07 | −.03 | .08 | - |

Note. Parent and adolescent discrimination measures and ethnic socialization were drawn from Wave 1; adolescent psychosocial adjustment measures from Wave 2

Linking Parent Discrimination to Adolescent Adjustment

A series of hierarchical linear regressions were run to address the first research aim. The model predicting internalizing problems revealed that after accounting for the controls (i.e., gender, grade, generational status, school, parent education, whether mother was primary caregiver, adolescent discrimination and Wave 1 internalizing problems), parent discrimination was a significant predictor (Table 2). As parent reports of discrimination increased, there was an increase in their adolescents’ internalizing problems one year later. Parent reports of discrimination also were related to adolescents’ self-esteem. As experiences with discrimination increased among parents, adolescents reported lower self-esteem one year later. As shown in Table 2, the models predicting externalizing problems and substance use revealed that parent discrimination did not predict these adjustment indicators. Thus, there was no relation between parent discrimination and adolescent’s externalizing problems or substance use. An additional model was run with a substance use scale that excludes more serious and infrequently used drugs (i.e., cocaine, crystal meth, illegal drugs, prescription drugs without a prescription). However, parent discrimination experiences did not predict the use of more commonly used substances and the results remained the same.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Adolescent Psychological Adjustment at Wave 2

| Internalizing Problems |

Self-Esteem | Externalizing Problems |

Number of Substances Used |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||

| Gender | .08 | 1.68 | .04 | .76 | −.01 | −.11 | .04 | .52 |

| Grade | −.04 | −.90 | .05 | .96 | −.03 | −.63 | −.04 | −.53 |

| 2nd Generation | .09 | 1.35 | −.19 | −2.54* | .03 | .39 | −.02 | −.23 |

| 3rd Generation | −.01 | −.13 | −.14 | −1.83 | .02 | .33 | −.02 | −.17 |

| School | .04 | .77 | −.01 | −.26 | .05 | 1.22 | .02 | .33 |

| Parent Educ. Secondary | .01 | .12 | .09 | 1.42 | .03 | .49 | −.01 | −.15 |

| Parent Educ. College | −.01 | −.11 | .13 | 2.05 | .03 | .52 | .03 | .38 |

| Mother Caregiver | −.02 | −.35 | .01 | .19 | .02 | .37 | .12 | 1.69 |

| W1 Outcome | .59 | 12.30*** | .45 | 8.85*** | .63 | 13.73*** | .02 | .33 |

| W1 Adolescent Discrimination | .01 | .16 | .01 | .07 | .07 | 1.51 | −.11 | −1.56 |

| Step 2 | ||||||||

| Parent Discrimination | .12 | 2.59* | −.14 | −2.71** | .03 | .61 | .02 | −.32 |

Note. Comparison groups include males, ninth grade, first generation adolescents, elementary school education and mother caregivers.

The Moderating Role of Ethnic Socialization

The results from the hierarchical regressions that tested the moderation hypotheses revealed that the main effect of cultural socialization was significant in predicting all of the psychological adjustment indicators except number of substances used. The main effect pattern showed that more cultural socialization messages predicted lower internalizing problems (b = −.74, SE = .38, p = .05) and lower externalizing problems (b = −.74, SE = .35, p = .04). Moreover, higher cultural socialization predicted higher self-esteem (see Table 3). The main effects of preparation for bias and promotion of mistrust were not significant for any of the outcomes.

Table 3.

Moderating Effect of Parent Ethnic Socialization on Adolescent Self-Esteem

| Cultural Socialization |

Preparation for Bias | Promotion of Mistrust |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Gender | .03 | .65 | .04 | .78 | .03 | .67 |

| Grade | .05 | .94 | .05 | .94 | .04 | .84 |

| 2nd Generation | −.19 | −2.59* | −.19 | −2.54* | −.21 | −2.86** |

| 3rd Generation | −.14 | −1.90 | −.15 | −1.92 | −.17 | −2.15* |

| School | −.03 | −.49 | −.03 | −.50 | −.02 | −.40 |

| Parent Educ. Secondary | .10 | 1.63 | .09 | 1.53 | .08 | 1.35 |

| Parent Educ. College | .13 | 2.04* | .14 | 2.21* | .12 | 1.91 |

| Mother Caregiver | .01 | .17 | .01 | .15 | .01 | .02 |

| W1 Self-Esteem | .42 | 8.21*** | .45 | 8.97*** | .44 | 8.54*** |

| W1 Adolescent Discrimination | −.02 | −.44 | −.01 | −.21 | .03 | .48 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| W1 Parent Discrimination | −.15 | −2.91** | −.14 | −2.67** | −.13 | −2.46* |

| W1 Ethnic Socialization | .14 | 2.62** | .08 | 1.44 | −.06 | −1.06 |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Disc X Ethnic Socialization | −.12 | −2.34* | −.12 | −2.33* | −.10 | −1.97* |

Note. In each model, the corresponding ethnic socialization measure is entered in step 2 and in the final step as a cross-product with parent discrimination.

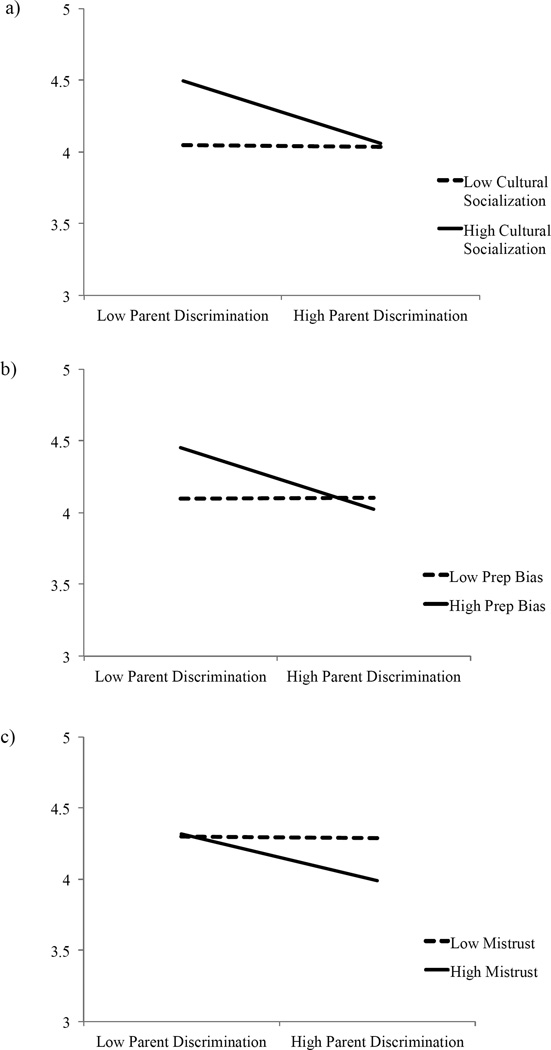

Across the three ethnic socialization indicators there was significant moderation in the models predicting self-esteem (Table 3). As shown in the top panel of Figure 1, the interaction between cultural socialization and self-esteem revealed that there was no association between parent discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem among adolescents who reported low levels of cultural socialization. Among adolescents who reported high levels of cultural socialization (encouragement to learn about culture), however, more parent discrimination was associated with lower adolescent self-esteem. A similar pattern was found for preparation for bias and promotion of mistrust (Figure 1). Among adolescents who reported low levels of parental preparation for bias or levels of mistrust messages from their parents, there was no association between discrimination and self-esteem. In contrast, if teens reported that their parents frequently taught them about ethnic discrimination (i.e., high preparation for bias) or they received frequent messages about mistrusting people of other ethnic groups, more parental experiences with discrimination were associated with lower self-esteem among adolescents. There were no interactions predicting internalizing symptoms, externalizing problems or substance use.

Figure 1.

Ethnic socialization moderations with adolescent self-esteem

Discussion

The current study adds to the growing literature investigating the impact of discrimination among Mexican-American adolescents. This study extends previous work by showing that parent’s experiences with discrimination were related to adolescent internalizing symptoms and self-esteem but not externalizing problems and substance use, one year later. The results indicate that cultural socialization is, on average, related to higher levels of self-esteem and lower levels of internalizing and externalizing problems. Cultural socialization remains a predictor of self-esteem, internalizing and externalizing problems across the one year timeframe of the study, even controlling for prior levels of the adjustment outcome and adolescent experiences of discrimination. This finding affirms the importance of cultural socialization in the lives of Mexican American adolescents (Knight et al., 2011). However, within this broader context of positive relationships with cultural socialization, a more nuanced picture emerges when considering the interaction between parents’ ethnic socialization messages and discrimination experiences in predicting self-esteem.

Parent discrimination predicts significantly lower levels of self-esteem in families in which parents are actively discussing or educating their adolescents about their cultural background and culturally-based societal biases such that the benefits of high ethnic socialization are offset when parents report high levels of discrimination. These findings suggest that it may be especially difficult for parents to shield their adolescents from threats to their self-esteem when they have been recent victims of discrimination. These parents may be less able to offer helpful messages to promote understanding of culture and bias, potentially still struggling to make sense of such events themselves. It is also possible that parents are offering effective messages, yet adolescents feel more threatened or less convinced of these messages if they observe that their parents experience unfair treatment. Researchers studying ethnic socialization have noted that future research should examine the overlap in what parents believe they are teaching their teens and what teens actually take away and understand from these messages (Romero, Gonzalez, & Smith, 2015). Furthermore, Brega and Coleman (1999) concluded from their study on the impact of ethnic socialization on subjective stigmatization among African-American adolescents, that highly frequent ethnic socialization messages may become “too much for the adolescent to handle”. This may be particularly true, when these messages are coupled with high levels of discriminatory acts experienced by parents, as found in the current study. If replicated in other studies, qualitative research would be useful to further explore whether parents give different types of messages when they are actively experiencing discrimination and the ways in which adolescents interpret parents’ messages at such times.

In contrast to the results for cultural socialization and preparation for bias, the moderating effects of promotion of mistrust were consistent with some formulations of this aspect of ethnic and racial socialization (Hughes et al., 2006). Parents’ discrimination had significantly more deleterious effects on adolescents self-esteem when it was combined with high levels of parents’ promotion of mistrust, and this combination was associated with the lowest levels of self-esteem. It is also noteworthy that the significant interactions shown in the prediction of self-esteem are driven, in part, by the fact that parents’ discrimination had no effects on self-esteem when parents were not actively engaged in the socialization of their adolescents. Perhaps these parents are less likely to discuss cultural issues and events with their adolescents, including their own experiences with discrimination. As a result, these adolescent are neither placed at greater risk yet neither do they derive the significant self-esteem benefits associated with ethnic socialization of Mexican-American youth. Overall, these findings highlight the difficulty that parents face in teaching their children about their culture and the role of culture in their lives. Saying nothing may deprive adolescents of important opportunities to achieve a strong sense of self, yet the specific types of message and the contexts in which they are delivered are also important for predicting self-esteem for Mexican American adolescents.

One question that emerges from the moderation results is why only self-esteem is associated with discrimination incidents and ethnic socialization messages. Self-esteem has been identified as a dimension of adolescent self-concept that is highly sensitive to individuals’ awareness of their membership in a group that is devalued (Crocker, Luhtanen, Blaine, & Broadnax, 1994; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). Self-esteem is also proposed to be sensitive to expectations of future discrimination experiences (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999). Thus, some knowledge or awareness that their parents are discriminated against coupled with frequently receiving messages that increase their awareness of potential bias or that even merely teach adolescents about their ethnic minority heritage may be signaling to them that their group is devalued and that discrimination is a salient experience for their family. Additionally, research shows that threats to an individual’s social identity are more impactful when one’s ethnicity is made more salient (Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002). Taken together, this is likely to lead to less positive feelings about oneself among Mexican-American adolescents. Much of the research examining relations between discrimination and adolescent outcomes have focused on socio-emotional and academic indicators (e.g., Huynh & Fuligni, 2010), with fewer studies examining links with externalizing behaviors. The current study found that parent experiences with discrimination were not predictive of Mexican-American adolescents’ externalizing problems or substance use. More research is needed to test whether associations exist between discriminatory incidents and related outcomes among ethnic minority adolescents.

The use of both parent and adolescent reports, longitudinal data and the inclusion of multiple indicators of psychosocial adjustment are strengths of the study. Yet, there are also limitations that should be considered. One limitation is that whether adolescents’ were aware of their parent’s discrimination experiences or whether they directly observed any incidents is unknown. Future studies should ask parents whether they discussed these particular experiences with their children or if they observed any incidents. This would better illuminate the extent to which explicit awareness of parent’s discrimination is related to adolescent well-being. A greater understanding of parent’s experiences with discrimination would also be insightful for future research. For example, in the current study we did not ask about phenotype or differentiate between inter- and intra-group discrimination. However, discrimination based on phenotype has been found to be relevant in the lives of Mexican-Americans (e.g., Romero, Gonzalez, & Smith, 2015) and perhaps this type of discrimination is particularly impactful and differentially related to ethnic socialization practices among parents. Future research would also benefit from continuing to study longitudinal associations across a wider time span that can better incorporate a life course perspective to understand whether discrimination experiences may have a unique impact during the adolescent period (Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersman, 2005). Finally, a limitation of the current study is that a majority of students were second-generation. Thus, there was not sufficient variability to examine whether the associations between parent discrimination and adolescent adjustment vary by generational status. Some evidence indicates that U.S.-born Latinos experience more discrimination incidents (e.g., Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008) than foreign-born Latinos. Nonetheless, it may be the case that associations are stronger among first generation adolescents who may be especially impacted by parent’s negative experiences since they tend to have closer family ties (e.g., Almeida, Molnar, Kawachi, & Subramanian, 2009) than later generations.

In sum, the current multi-wave, multi-informant study advances our understanding of discrimination among an understudied population, Mexican-American families. Future research should continue to examine culturally relevant factors such as ethnic identity and acculturative stress to help elucidate associations between parents’ experiences with discrimination and adolescent psychosocial adjustment.

Acknowledgments

Author acknowledgments: The research was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD057164) and the UCLA California Center for Population Research, which is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24-HD041022). The content does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the school principals, teachers and students for their participation in this project.

Contributor Information

Guadalupe Espinoza, California State University, Fullerton, guadespinoza@fullerton.edu, office phone: 657-237-2354, 800 N. State College Blvd., Fullerton, Ca 92831.

Nancy A. Gonzales, Arizona State University

Andrew J. Fuligni, University of California, Los Angeles

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Molnar BE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1852–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Kim SY. Intergenerational experiences of discrimination in Chinese American families: Influences of socialization and stress. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:862–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein J, Roosa MW, Gonzales NA, Saenz D. Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally related values. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Brega AG, Coleman LM. Effects of religiosity and racial socialization on subjective stigmatization in African-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22:223–242. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MO, O’Campo PJ, Muntaner C. Experiences of racism among African American parents and the mental health of their preschool-aged children. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94 doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker L, Luhtanen R, Blaine B, Broadnax S. Collective self-esteem and psychological well-being among White, Black, and Asian college students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Evans AB, Banerjee M, Meyer R, Aldana A, Foust M, Rowley S. Racial socialization as a mechanism for positive development among African American youth. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, McQuillin SD. Evaluating mediation and moderation effects in school psychology: A presentation of methods and review of current practice. Journal of School Psychology. 2010;48:53–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KR, Hurd NM, Jagers RJ, Sellers RM. Caregiver experiences of discrimination and African American adolescents’ psychological health over time. Child Development. 2013;84:485–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1897–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, Rowey SJ. Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African-American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children’s mental health: Low income Mexican-American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74:189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. When and what parents tell children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Applied Developmental Science. 1997;1:200–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DK, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, Fuligni AJ. Discrimination hurts: The academic, psychological, and physical well-being of adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:916–941. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperminc GP, Wilkins NJ, Jurkovic GJ, Perilla JL. Filial responsibility, perceived fairness, and psychological functioning of Latino youth from immigrant families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:173–182. doi: 10.1037/a0031880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde RN, Jones JM, Stroink ML. Racial identity, racial attitudes, and race socialization among Black Canadian parents. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2008;40:129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. A longitudinal analysis of Hispanic youth acculturation and cigarette smoking: The roles of gender, culture, family and discrimination. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2013;15:957–968. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brown PA, Brody GH, Cutrona CE, Simons RL. Racial discrimination as a moderator of the links among stress, maternal psychological functioning and family relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:915–926. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, White RL, Ford KR, Philip CL, Nguyên HX, Sellers RM. Patterns of racial socialization and psychological adjustment: Can parental communications about race reduce the impact of racial discrimination? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:477–515. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegría M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Walton J, White F, Kowal E, Baker A, Paradies Y. Understanding the complexities of ethnic-racial socialization processes for both minority and majority groups: A 30-year systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2014;43:139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Gonzalez H, Smith BA. Qualitative exploration of adolescent discrimination: Experiences and responses of Mexican-American parents and teens. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24:1531–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Spencer SJ, Aronson J. Contenting with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 379–440. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]