Abstract

Tautomycetin (TMC) is a linear polyketide metabolite produced by Streptomyces sp. CK4412 that has been reported to possess multiple biological functions including T cell-specific immunosuppressive and anticancer activities that occur through a mechanism of differential inhibition of protein phosphatases such as PP1, PP2A, and SHP2. We previously reported the characterization of the entire TMC biosynthetic gene cluster constituted by multifunctional type I polyketide synthase (PKS) assembly and suggested that the linear form of TMC could be generated via free acid chain termination by a narrow TMC thioesterase (TE) pocket. The modular nature of the assembly presents a unique opportunity to alter or interchange the native biosynthetic domains to produce targeted variants of TMC. Herein, we report swapping of the TMC TE domain sequence with the exact counterpart of the macrocyclic polyketide pikromycin (PIK) TE. PIK TE-swapped Streptomyces sp. CK4412 mutant produced not only TMC, but also a cyclized form of TMC, implying that the bioengineering based in vivo custom construct can be exploited to produce engineered macrolactones with new structural functionality.

Keywords: thioesterase, domain swapping, linear polyketide, tautomycetin, pikromycin

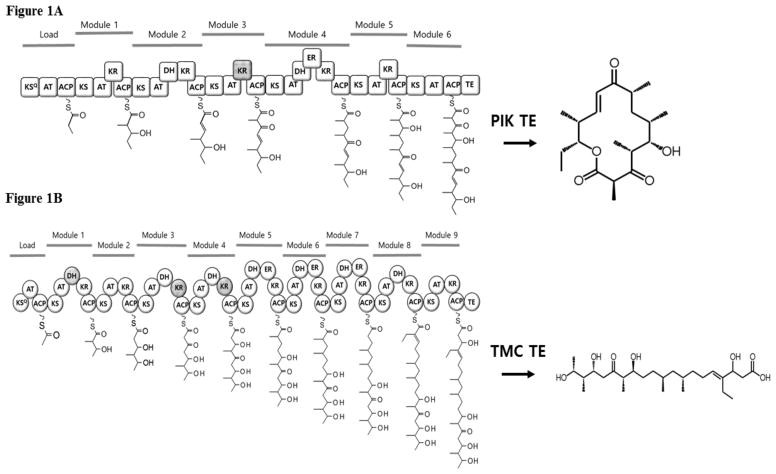

Polyketides are a diverse family of natural products with highly significant medicinal properties exemplified by innumerable FDA approved commercial drugs [14]. Many of the lucrative polyketides are proficiently assembled by biosynthetic gene clusters encoding type I polyketide synthases (PKS) enzymes. The modular functionality of these catalytic enzymes involves sequential initiation, elongation and extension steps of the polyketide scaffolds [3]. The enzymatic deconstruction of multi-domain fragments can be potentially re-engineered/reprogrammed (termed “lego-ization”) for targeted small molecule biosynthesis through genetic manipulations [11]. PKS modules of the biosynthetic cluster are generally encoded as keto-synthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP) for carboxyl acid synthesis, and ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH) and enoylreductase (ER) domains for reduction processes. The modularly processed metabolites are finally presented to the termination module thioesterase domain (TE), which cleaves the functionalized polyketide chain to yield the concluding product [7]. Type I PKS TEs are specific in the chemistry they catalyze, producing metabolites either through macrocyclization, such as the pikromycin (PIK) [10, 13], or through hydrolysis, such as in baulamycins and tautomycetin (TMC) [Fig. 1] [2, 12]. The pikromycin biosynthetic pathway, which is involved in producing 12- and 14- membered macrolactones from Streptomyces venezuelae, has been extensively studied both structurally and functionally [1,8]. The pathway yields two ring sizes due to the skipping of the terminal polyketide synthase module rather than the selectivity of TE between two possible nucleophiles [5]; however, the ability of PIK TE to accommodate different ring sizes in its large substrate binding tunnel is unique. In comparison, the biosynthetic assembly of TMC only produces linear polyketides through hydrolysis, catalyzed by the TE domain. The structure of TMC TE was recently analyzed, and the results suggested that the linear chemical structure of TMC is strictly determined by the pocket size of the active site involved in terminal processing of polyketides [10]. Further inspection of the shape and size of the active site tunnel in TMC TE revealed that the bulky side chains of Tyr161, Phe163 and Leu205 could constrict the exit side of the substrate tunnel, leaving only enough space for an extended acyl chain, rather than a macrocycle [10].

Figure 1.

Proposed steps in the PIK (A) and TMC (B) polyketide biosynthetic pathway. KS= ketosynthase, AT= acyltransferase, ACP= acyl carrier protein, DH= dehydratase, KR= ketoreductase, ER= enoylreductase, TE= thioesterase. Domains predicted to be inactive are crossed out. Domains that are active but not utilized are indicated with a star.

We previously functionally characterized the entire TMC biosynthetic and regulatory pathway gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. CK4412 and demonstrated its identity by gene disruption and complementation analysis [9]. The TMC biosynthetic gene cluster revealed two multimodular Type I PKS assemblies, as well as 18 ORFs located at both flanking regions, the deduced functions of which were consistent with TMC biosynthesis. When both PKSs were analyzed, they were found to have 10 modules, with the TE domain located in the last module as expected. Earlier studies examining the ability of the TMC TE to catalyze the intramolecular cyclization of the linear pikromycin hexaketide intermediate suggested a high degree of stereoselectivity at the β-hydroxy position. In addition, the constrained active site pocket relative to macrolactone forming PIK TE rendered the processing of any substrate completely unproductive towards cyclization [10]. The strict catalytic activity observed in such proteins/enzymes is probably acquired through evolutionary pressure [4]. However, the same pressure also results in highly conserved DNA sequences among various secondary metabolic clusters. This often leads to ‘hybridization’ between two evolutionary distinct, but sequentially similar gene clusters to increase genetic and consequential chemical diversity [15]. Thus, we envisioned the terminal swapping of the TMC TE domain with the exact counterpart of the macrocyclic polyketide PIK TE to analyze the full length processing capability of the constructed TMC-pikTE cluster to catalyze any possible 12 or 14 membered rings.

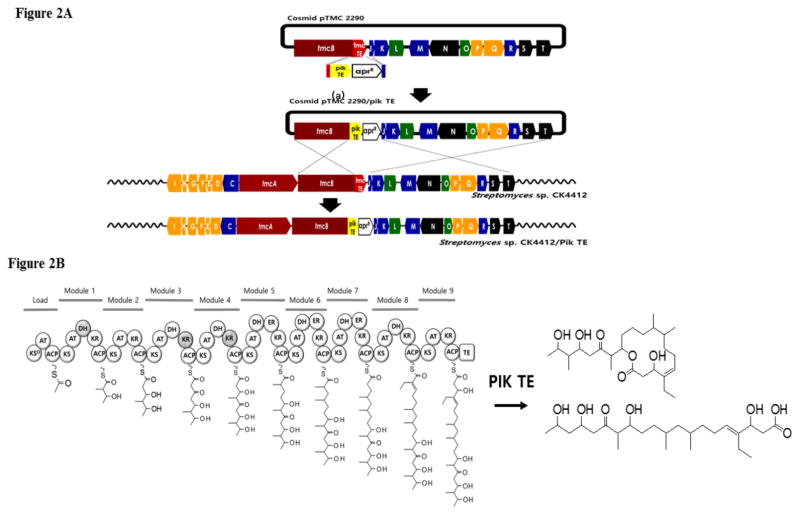

To characterize the ability of swapped domains to conduct full length processing of substrate intermediates we substituted the TMC TE with the PIK TE using a PCR targeted gene disruption system (Fig. 2A). First, the PIK TE domain in PKS PikAIV was isolated from S. venezuelae by PCR. The PCR product was amplified without including the linker between the ACP domain and PIK TE domain, which avoided the overlap of linkers in front of TMC TE. After the PCR product was fused with apramycin resistance marker, it was inserted behind the linker located between the PKS ACP domain and the TMC TE domain in the TMC cluster of the pTMC2290 cosmid to replace the TMC TE. The replacement pertaining to the homologous recombination of TE domains was confirmed by PCR and sequencing of the selected colonies containing pTMC2290:: pik TE cosmid [9]. The mutant cosmid was then transformed through conjugation into Streptomyces sp. CK4412 host from E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 harboring the pTMC2290:: pik TE via conjugation and the strain Streptomyces sp. CK4412-pikTE was obtained following double reciprocal recombination as shown in Fig. 2A. Next, we sought to determine the possible product of heterologously expressed Streptomyces sp. CK4412-PIK TE upon induction. To verify the expression of expressed chimeras, the mutants were grown for 7 days at 28°C on a MS agar plate then subjected to organic extraction using ethyl acetate. To isolate the TMC-like compounds, transconjugant cells cultured on MS plates for 7 days at 28°C were ground with equal volumes of water, then adjusted to pH 4 with HCl. The acidic aqueous solution was extracted with equal volumes of ethyl acetate. Ethyl acetate was removed under vacuum using a rotor evaporator to give crude products that were attached to a reverse silica gel.

Figure 2.

Schematic description of the TE domain swapping approach (A) and proposed structure of cyclized TMC analogue (B). TmcA and tmcB, type I polyketide synthase; tmcC-I and tmcP-Q, diakylmaleic anhydride moiety processing; tmcJ and tmcK, decarboxylase; tmcL, crotonyl-CoA reductase; tmcM, dehydratase; tmcN and tmcT, pathway-specific regulator; tmcO, thioesterase; tmcR, cytochrome P450; tmcS, transporter

The plausible cyclized molecules were predicted based on the ability of PIK TE to catalyze macrolactonization through ester bond formation. The Streptomyces sp. CK4412-pik TE isolates were examined by sequential HPLC analysis followed by diagnostic NMR experiments conducted over Varian INOVA 700 MHz. High-resolution APCIMS spectra were measured at the University of Michigan core facility in the Department of Chemistry using an Agilent 6520 Q-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with an Agilent 1290 HPLC system. RP-HPLC was conducted using a Waters Atlantis® Prep T3 OBD™ 5 μm 19 × 250 mm column, a Luna 5 μm C8(2) 100 Å, AXIA packed column and a solvent system of MeCN and H2O. The LCMS analysis of HPLC fractions was conducted using a Shimadzu 2010 EV APCI spectrometer. Any conceivable HPLC peaks with distinct polyketidic functionalities observed through NMR were subsequently subjected to LCMS, and the TIC trace of organic extract clearly showed the presence of a [M+Na]+ peak at 477.80 and a [M−H2O+Na]+ peak at 459.60, suggesting the molecular formula of C26H46O6 with 4 degrees of unsaturation. In addition, a small amount of linear TMC was also detected in the PIK TE-swapped Streptomyces sp. CK4412, which is conceivable, as all the post-PKS modifying genes were still intact in the cluster. The formula C26H46O6 detected for the new molecule suggested at least three possible downstream processing products of TMC by TMC-PikTE chimera to produce a macrolactone (Fig. S1). Motivated by the experimental observation, we attempted to purify the cyclized molecule through HPLC of the crude extract. However, the analysis clearly suggested that the hybrid chimera only sparsely produced the possible cyclized molecule in vivo and there was not enough material for NMR structural characterization. Therefore, we decided to pursue the complete structural characterization by means of HRMS and MS/MS data that could be obtained from sub nanogram levels of sample. HRMS data with MS/MS fragmentation was acquired by optimizing the collision energy of qTOF to 20V against the observed parent mass of [M−2H2O+Na]+ and [M−3H2O+Na]+ of 441.3708 and 423.3608, respectively. The procured data suggested a distinct fragmentation pattern of the molecule to generate credible fragments with m/z 111.0551 and a larger portion with 310.4715. The masses obtained unambiguously indicated the formation of 14 membered macrolactone with m/z at 333.2159 [310.4715+Na]+ and m/z at 111.0551 [146.1843−2H2O+H]+, suggesting the presence of a functionalized 7 carbon long aliphatic chain at C-13 in the macrolactone with the TMC organic backbone. The observation was further substantiated by the MS/MS profile of the 14 membered macrolactone to produce at-least two fragments with m/z at 138.0656 [115.0759+Na]+ and 203.1785 [197.1827−H2O+Na]+ [Fig. S2], confirming the presence of a completely processed new macrolactone TMC analogue [Fig. 2B]. Moreover, the structure of the macrolactone TMC analogue corroborates with the inherent ability of PIK TE to efficiently catalyze the formation of its native 14 and 12 membered rings, pikromycin and 10-deoxymethynolide, respectively [1, 8].

In summary, we provide here a proof of concept towards the lego-ization of polyketide biosynthesis by swapping the TMC TE domain that yields linear polyketide with a PIK TE domain that produces macrolactones to create a chimeric PKS hybrid and biologically synthesize a novel cyclized TMC derivative [11]. However, the low yield of the molecule directly reflects the importance of the TE in catalytic turnover and efficient accrual of products. Proficient activities of TEs are mostly concealed until compatible substrates are dispensed from their corresponding upstream domains; therefore, it is not surprising that the processing of the new molecule is diminished to a large extent. Accordingly, future studies are required to further refine this process. Our current scientific knowledge is limited by the delicate and complicated structure of the PKS assembly for determining linearity or cyclization of a polyketide chain. Therefore, an efficient technique based on this study for the manipulation of secondary metabolite clusters can play a crucial role in diversifying the chemical scaffolds belonging to the polyketide class of molecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Global Research Network Program (NRF-2011-220-D00040) and the Basic Science Research Program (NRF-2014R1A2A1A11052236) through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

References

- 1.Chen S, Xue Y, Sherman DH, Reynolds KA. Mechanisms of molecular recognition in the pikromycin polyketide synthase. Chem Biol. 2000;7(12):907–918. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi SS, Hur YA, Sherman DH, Kim ES. Isolation of the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster for Tautomycetin, a Linear Polyketide T Cell-Specific Immunomodulator from Streptomyces sp. CK4412. Microbiology. 2007;153:1095–1102. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/003194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutta S, Whicher JR, Hansen DA, Hale WA, Chemler JA, Congdon GR, Narayan AR, Håkansson K, Sherman DH, Smith JL, Skiniotis G. Structure of a modular polyketide synthase. Nature. 2014;510(7506):512–517. doi: 10.1038/nature13423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falanga A, Stojanović O, Kiffer-Moreira T, Pinto S, Millán JL, Vlahoviček K, Baralle M. Exonic splicing signals impose constraints upon the evolution of enzymatic activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(9):5790–5798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han AR, Park JW, Lee MK, Ban YH, Yoo YJ, Kim EJ, Kim E, Kim BG, Sohng JK, Yoon YJ. Development of a Streptomyces venezuelae-based combinatorial biosynthetic system for the production of glycosylated derivatives of doxorubicin and its biosynthetic intermediates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:4912–4923. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02527-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopwood DA. Genetic Contributions to Understanding Polyketide Synthases. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2465–2497. doi: 10.1021/cr960034i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khosla C, Gokhale RS, Jacobsen JR, Cane DE. Tolerance and Specificity of Polyketide Synthases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:219–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortison JD, Kittendorf JD, Sherman DH. Synthesis and biochemical analysis of complex chain-elongation intermediates for interrogation of molecular specificity in the erythromycin and pikromycin polyketide synthases. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(43):15784–15793. doi: 10.1021/ja9060596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nah JH, Park SH, Yoon HM, Choi SS, Lee CH, Kim ES. Identification and characterization of wblA-dependent tmcT regulation during tautomycetin biosynthesis in Streptomyces sp. CK4412. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30(1):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scaglione JB, Akey DL, Sullivan R, Kittendorf JD, Rath CM, Kim ES, Smith JL, Sherman DH. Biochemical and structural characterization of the tautomycetin thioesterase: analysis of a stereoselective polyketide hydrolase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(33):5726–5730. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman DH. The Lego-ization of polyketide biosynthesis. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1083–1084. doi: 10.1038/nbt0905-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tripathi A, Schofield MM, Chlipala GE, Schultz PJ, Yim I, Newmister SA, Nusca TD, Scaglione JB, Hanna PC, Tamayo-Castillo G, Sherman DH. Baulamycins A and B, broad-spectrum antibiotics identified as inhibitors of siderophore biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus anthracis. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(4):1579–1586. doi: 10.1021/ja4115924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson B, Micklefield J. Mining and engineering natural-product biosynthetic pathways. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;7:379–386. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Demain AL. Natural Products: Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Medicine. Humana Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zucko J, Long PF, Hranueli D, Cullum J. Horizontal gene transfer and gene conversion drive evolution of modular polyketide synthases. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;39(10):1541–1547. doi: 10.1007/s10295-012-1149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.