Abstract

Pediatric healthcare networks serve millions of children each year. Pediatric illness and injury are among the most common potential emotionally traumatic experiences for children and their families. Additionally, millions of children who present for medical care (including well visits) have been exposed to prior traumatic events such as violence or natural disasters. Given the daily challenges of working in pediatric healthcare networks, medical providers and support staff can experience trauma symptoms related to their work. The application of a trauma-informed approach to medical care has the potential to mitigate these negative consequences. Trauma-informed care minimizes the potential for medical care to become traumatic or trigger trauma reactions, addresses distress and provides emotional support for the entire family, encourages positive coping, and provides anticipatory guidance regarding the recovery process. When used in conjunction with family-centered practices, trauma-informed approaches enhance quality of care for patients and their families and the wellbeing of medical care providers and support staff. Barriers to routine integration of trauma-informed approaches into pediatric medicine include a lack of available training and unclear best practice guidelines. This paper highlights the importance of implementing a trauma-informed approach and offers a framework for training pediatric healthcare networks in trauma-informed care practices.

Every year in the United States, over 22 million children visit the emergency department,1 6 million are hospitalized,2 and nearly 16 million receive outpatient care in pediatric hospitals.3 Medical events and subsequent care can be challenging for children and families, often resulting in significant adverse psychological reactions (e.g., posttraumatic stress).4–7 In addition to exposure to potentially emotionally traumatic medical events, two-thirds of individuals have been exposed to at least one other traumatic event during their childhood (e.g. abuse, neglect, witnessing violence).8 These exposures place children at-risk for emotional, physical, and functional impairment.9,10 Given the high prevalence of trauma exposure among youth, the impact of emotional trauma, and the role of pediatric providers in facilitating healthy child development, pediatric healthcare networks are an ideal setting to implement a trauma-informed approach to medical care, thereby mitigating the negative effects of trauma exposure.11,12 Many pediatric facilities have embraced the concept of family centered care and have effectively changed the culture of care provision to the benefit of patients, families, and healthcare providers. However, training in the delivery of trauma-informed care is not routinely integrated into education for healthcare professionals and support staff.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA) definition is among the most comprehensive and widely employed and thus can be used in guiding the application of trauma-informed care in pediatric healthcare networks (See Table 1 for other definitions). Throughout this paper, “trauma” refers to emotional trauma, not physical injury, and trauma-informed care refers to how medical teams can prevent or minimize emotional trauma. According to SAMHSA, a trauma-informed approach encompasses how programs, organizations, and broader systems understand and respond to those who have experienced or may be at risk for experiencing traumatic events. The trauma-informed approach incorporates four key elements: 1) realizing the widespread impact of trauma; 2) recognizing how trauma may affect clients, staff, and others in the program, organization, or system; 3) responding by applying knowledge about trauma into practice; and 4) preventing re-traumatization.13 Implementing a trauma-informed approach in a medical facility involves transforming the organizational culture, including the policies, procedures, and practices that impact its own workforce, patients, and families. A trauma-informed approach incorporates an understanding of trauma into routine care and treatment of illness or injury with a goal of decreasing the effect of potentially traumatic events.12,14 This includes recognizing and addressing pre-existing emotional trauma reactions as well as new trauma reactions related to medical events and care.15

Table 1.

Definitions of Trauma-Informed Approaches

| Institution | Definition | Further Reading |

|---|---|---|

| National Center for Trauma-Informed Care | A strengths-based delivery approach grounded in an understanding of and responsiveness to the impact of trauma, that emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety for both providers and survivors, and that creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment. Involves vigilance in anticipating and avoiding institutional processeses and individual practices that are likely to retraumatize individuals who already have histories of trauma, and it upholds the importance of consumer participation in the development, delivery, and evaluation of services. |

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services Treatment Improvement Protocol available free of charge at http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA14-4816/SMA14-4816.pdf |

|

| ||

| Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] | A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed: 1) Realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; 2) Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; 3) Responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and 4) Seeks to actively resist re-traumatization. A trauma-informed approach adheres to six key principles: Safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues. | http://beta.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions |

|

| ||

| National Child Traumatic Stress Network | A service system in which all parties recognize and respond to the impact of traumatic stress on those who have contact with the system including children, caregivers, and service providers. Programs and agencies within such a system infuse and sustain trauma awareness, knowledge, and skills into their organizational cultures, practices, and policies. Programs, agencies, and service providers: (1) routinely screen for trauma exposure and related symptoms; (2) use culturally appropriate evidence-based assessment and treatment for traumatic stress and associated mental health symptoms; (3) make resources available to children, families, and providers on trauma exposure, its impact, and treatment; (4) engage in efforts to strengthen the resilience and protective factors of children and families impacted by and vulnerable to trauma; (5) address parent and caregiver trauma and its impact on the family system; (6) emphasize continuity of care and collaboration across child-service systems; and (7) maintain an environment of care for staff that addresses, minimizes, and treats secondary traumatic stress, and that increases staff resilience. | http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/creating-trauma-informed-systems |

|

| ||

| Fallot & Harris, 2008 | Trauma-informed systems and services are those that have thoroughly incorporated an understanding of trauma, including its consequences and the conditions that enhance healing, in all aspects of service delivery. | Fallot, R. D., & Harris, M. (2008). Trauma-informed approaches to systems of care. Trauma Psychology Newsletter, 3(1), 6–7. |

Given that healthcare systems are complex entities involving disciplines and subspecialties across multiple levels of care, implementing trauma-informed practices can be challenging. Clear guidelines for a trauma-informed approach within pediatric healthcare care networks do not exist. Thus, this review has two primary aims. First, we summarize and integrate research regarding the prevalence and impact of emotional trauma as it relates to pediatric healthcare networks. Next, we make recommendations for training healthcare professionals and staff in pediatric healthcare networks in how to integrate a trauma-informed approach into the provision of medical care.

Realizing the Prevalence of Trauma in Children

Potentially traumatic events (PTE) are defined as those in which an individual experiences or witnesses actual or threatened death or serious injury to oneself or others.16 In the US, it is estimated that 60% of children have been exposed to a PTE within the past year.17 Two-thirds of individuals have experienced at least one type of potentially traumatic event during childhood.8 Although some children are exposed to trauma in highly publicized, large-scale events (e.g., natural disasters, school shootings), the vast majority of childhood PTEs involve lower-profile events such as abuse, community violence, accidental injury, motor vehicle crashes, and exacerbation of chronic illnesses.9,18–21

Many PTEs require children and families to interact with pediatric hospitals and other healthcare settings. Unfortunately, because medical care may include painful, invasive, or frightening procedures, treatment itself can also be traumatic for children and families.11 The recurrent nature of treatment experiences in severely ill and/or injured children can compound traumatic reactions.22 A trauma-informed approach allows care providers to understand that many patients and their parents may have experienced prior PTEs and that these experiences impact how they experience medical care.22

Recognizing the Impact of Trauma on All Individuals within the Healthcare System

Impact of Trauma on Children and Families

The wide range of psychobiological consequences to trauma has been described using a variety of terms. In mental health disciplines, psychological responses to trauma are categorized as posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS). These include re-experiencing or intrusive thoughts, avoidance of trauma reminders, hyperarousal, dissociation, and negative changes in mood or cognition.16 Specific to medical trauma, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN)23 has defined medical traumatic stress as a “set of psychological and physiological responses of children and their families to pain, injury, serious illness, medical procedures, and invasive or frightening treatment experiences.” Among medically involved children, PTSS are a key predictor of functional outcomes and health-related quality of life, interfere with adherence, and are linked to poorer health outcomes.24–28 Ongoing trauma has been labeled toxic stress, defined as excessive, frequent, or prolonged activation of physiological stress response systems in the absence of the protection afforded by stable relationships with adults.29 Toxic stress responses can occur as a result of adverse events such as abuse, neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and poverty. Toxic stress may disrupt the development of brain circuitry and other physiological systems, which in turn can heighten risk for impairments in cognitive development, behavioral and psychological functioning, and physical health well into the adult years.29,30

Traumatic stress reactions are common after a PTE. Most children and parents report at least one severe traumatic stress reaction during the first month after illness or injury.31,32 Some aspects of these reactions may even serve adaptive purposes. Naturally occurring processes of psychological recovery often involve balancing repeatedly thinking about a traumatic event with efforts to distract oneself or temporarily avoid distressing reminders. This interplay between re-experiencing and avoiding may facilitate recovery by allowing the individual to process and assimilate the distressing experience without becoming overwhelmed.33 In a trauma-informed system, pediatric providers can use this knowledge to help children and parents understand the temporarily distressing emotional reactions.

Although most children are resilient and display transient distress that decreases with time, a notable subset develop persistent and impairing PTSS following traumatic events. 19% of injured and 12% of ill children experience clinically significant PTSS.34 Similar rates have been documented among parents.31,35,36 Furthermore, approximately 13–50% of youth who are exposed to community or domestic violence, abuse, or neglect report significant PTSS.37,38 Many of these children and their parents go unrecognized and receive no treatment; therefore, it is crucial that the medical community be familiar with signs and symptoms of PTSS.

Medical systems that recognize the potential impact of trauma are exceptionally well positioned to identify and support children and families who are struggling to manage PTEs. Pediatric healthcare professionals who understand the potential role of early life adversity in the etiology of mental and physical health problems are better prepared to screen and intervene to address the consequences of trauma in the children and families they serve and achieve better outcomes. As it is not always possible or appropriate to screen for PTSS or collect information on a trauma history during every medical encounter (e.g., emergency care), providers can use a trauma-informed approach as a universal precaution. Thus, all children and families can be provided care as if they may have experienced trauma in the past or may be experiencing current medical care as traumatic; children can then be screened or referred for an assessment at a later time if indicated.

Impact of Trauma on Healthcare Providers and Staff

Beyond appreciating the impact of PTEs on patients and families, a trauma-informed approach must consider the experiences of individuals at all levels of an institution.13 In a pediatric hospital, first responders, medical providers, and support staff necessarily face repeated exposure to critically ill or injured children. The importance that pediatric professionals place on protecting children may make them particularly vulnerable to being traumatized by a child's suffering.39 Care providers are often responsible for conducting medical procedures that cause children to experience additional pain, discomfort, or fear. Depending on the intensity and duration of exposure to these PTEs, providers involved in a child's medical care may experience serious adverse outcomes including compassion fatigue and burnout.39,40,41,42 Compassion fatigue refers to work-related PTSS that arise from long-term exposure to other persons experiencing trauma. Burnout refers to a combination of symptoms including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment or workplace satisfaction.43 Compassion fatigue and burnout share a fundamental basis in caregiver traumatization, are each associated with suboptimal patient care (e.g., decreased provider empathic responses and professionalism, increased likelihood of medical errors and inappropriate prescribing practices) and patient attitudes and behaviors (e.g., lower adherence, satisfaction with care, and trust in medical providers).40,44–46 In a study of critical care pediatricians, 36% were classified as at risk for burnout, and 14% were considered already burned out.47 Robins and colleagues39 found that 39% of pediatric providers were at moderate to very high risk for compassion fatigue, and 21% were at moderate to high risk of burnout.39 Taken together, these findings indicate that individuals who provide care to critically ill or injured children are at serious risk for adverse mental health outcomes, which impact patient care. In addition, considering the prevalence of exposure to trauma in everyday life, many (if not all) healthcare personnel also have experienced PTEs outside of work.8 A culture of silence and lack of awareness led to these reactions among staff being unrecognized and unresolved.39,40

Responding by Integrating Knowledge of Trauma into Practice and Preventing Retraumatization

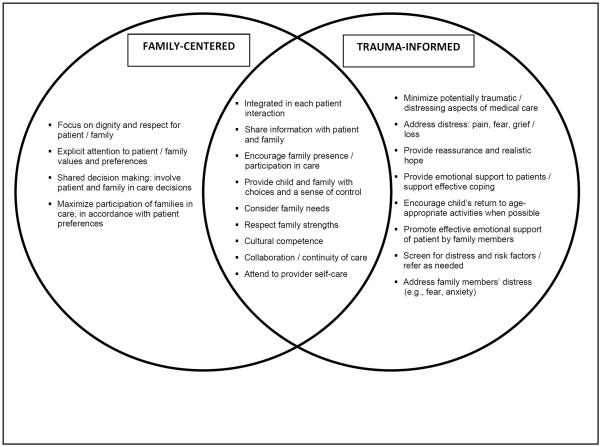

In settings that employ a family-centered approach to care, the addition of a trauma-informed approach is natural and offers several advantages. Family-centered and trauma-informed care approaches are complementary but offer unique contributions to promoting high quality pediatric healthcare (see Figure 1). Each approach emphasizes involving the entire family in care, ensuring cultural competence in care delivery, promoting collaboration among care providers and continuity of care, and engaging in self-care for providers.11,13,48 Trauma-informed care incorporates additional key elements including minimizing the potential for medical care to trigger or to serve as traumatic events, addressing distress and providing emotional support for the family, encouraging coping resources, and providing anticipatory guidance regarding recovery.11,13 When used in conjunction with family-centered practices, trauma-informed approaches enhance quality of medical care and the wellbeing of providers.

Figure 1.

Unique and overlapping elements of family-centered and trauma-informed pediatric care

The overlapping circles highlight shared elements of the family-centered and trauma-informed care approaches. Unique, complimentary elements of family-centered and trauma-informed care are displayed in the non-overlapping portions of the circles. Adapted with permission from HealthCareToolBox.org.50

Healthcare Providers' Role: Actions to Support Children During Medical Care

One trauma-informed approach that all direct care providers can adopt regardless of specialty is the DEF Protocol for Pediatric Healthcare Providers (see HealthCareToolBox.org).49 The DEF protocol provides an evidence-based method for healthcare providers to identify and address traumatic stress responses in children after illness or injury. After addressing the basics of physical health (i.e., the A-B-C's), providers can promote patients' emotional wellbeing and recovery by attending to D-E-F: reduce Distress, promote Emotional support, and remember the Family.50 While many of these techniques may be applied across settings, trauma-informed practices should be tailored to the specific provider's role and the population. For example, providers working with children with history of sexual abuse hospitalized for treatment of a physical illness should carefully consider how to approach children's nighttime care (e.g., asking children if they prefer to be awakened each time a provider enters the room). Healthcare professionals treating children with chronic illnesses should assess the range of procedures and treatment experiences that could be traumatic (e.g., needles, taking medications, MRIs, surgeries, peer teasing). Trauma-informed care also includes screening and referring a child for more support when needed (e.g., significant impairing symptoms, difficulty with bereavement). Healthcare organizations can provide general training for all providers and support staff with specialized training for each patient population, thereby ensuring that trauma-informed practices are implemented by all individuals across the pediatric healthcare network.

Training Pediatric Healthcare Networks in Trauma-Informed Care

Similar to the shift in the medical field from patient-centered to family-centered care, implementing trauma-informed care is a shift in culture. Lessons from the family-centered care movement can be applied to the implementation of trauma-informed care practices within pediatric healthcare settings. Specifically, institutions that have successfully adopted family-centered care models have emphasized the importance of integrating a family-centered philosophy into the mission, values, strategic plan, culture, and daily practices of the institution, partnering with patients and families as essential stakeholders in improving care practices. These institutions have emphasized family-centered competencies in all aspects of education for healthcare professionals, staff, and leadership, providing incentives and rewards for hospitals and units implementing family-centered care, and supporting research and evaluation to ensure evidence-based practice.51,52 As mentioned above, trauma-informed practices build on family-centered care; thus, for those networks already engaging in family-centered care, small shifts in knowledge, attitudes, and practices can result in a trauma-informed care network. Healthcare organizations with cultures marked by encouraging, compassionate, and emotionally-supportive patient interactions and those with norms of innovativeness may be particularly well-positioned to successfully implement trauma-informed care practices.53,54 Additionally, the diffusion of healthcare innovations in general is facilitated by perceived benefit of the change, compatibility of the values and needs of the organization, the complexity of the changes needed, individual characteristics of staff, collaboration between departments, formal reinforcements, sufficient skills, knowledge, and clear procedures.55,56

Training in trauma-informed practices ought to include information on realizing the prevalence of trauma in patients and staff, recognizing the impact of trauma, and responding with trauma-informed practices to prevent re-traumatization or new trauma. While medical professionals are receptive to taking a trauma-informed approach to medical care, regular training in trauma-informed care is not provided. Most pediatricians and emergency department providers agree that psychosocial issues are important,57,58 and the scientific basis for the impact of stress and life experiences on long term health resonates well with clinicians. However, research suggests that many underestimate the prevalence of psychological problems among children,59,60 are unaware of available tools to assess risk for PTSS,59 and report inadequate knowledge and skills related to assessing child mental health problems and PTSS.58,60 Only one in ten pediatricians frequently assess or treat PTSS,60 and only a small proportion of ED providers report giving any verbal guidance (18%) or written information (3%) about PTSS to children and their families.59 Moreover, among US level 1 trauma centers, there is marked variability in the implementation of psychosocial services, with only 20% reporting specialized PTSS screening and intervention services for children and families.61 These findings underline the importance of organizational readiness, assessment of unique organizational characteristics, and shifts in culture to facilitate trauma-informed care.62–64

Gaps in knowledge and skills can be addressed through training in trauma-informed approaches for healthcare providers. For example, a recent study found that pediatric nurses were fairly knowledgeable about and open to using a trauma-informed framework but that their current practice and self-rated competence varied most with regard to directly asking patients about traumatic events and educating parents and children about PTSS.65 Another study found high overall acceptability for the implementation of a PTSS screening tool among both ED staff and patients.66 These findings suggest that while providers value trauma-informed care practices, there are gaps in training, confidence, and support structures. To our knowledge, there is no published data on training support staff (e.g., schedulers, cafeteria workers, housekeepers) who regularly interact with children presenting for medical care and their parents; yet, they are repeatedly exposed to children and parents' reactions during times of significant stress. Institutions can alleviate these gaps by providing opportunities for on-the-job training specific to implementing trauma-informed practices.

Resources for training pediatric medical providers are beginning to grow. For example, the Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress (CPTS), a multidisciplinary intervention development center within the NCTSN, developed HealthCareToolBox.org, which provides videos, online continuing education courses, and handouts for children and parents with evidence-based guidance addressing medical traumatic stress.49 Hospital programs aimed at specific issues, such as youth violence, are adopting a trauma-informed approach and train hospital personnel and community based health workers,67 warranting a trauma-informed training section of the National Network of Hospital-based Violence Intervention Programs (www.NNHVIP.org). Additionally, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) offers a Trauma Toolbox for Primary Care (http://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Pages/Trauma-Guide.aspx), including resources for practitioners (e.g., addressing adverse childhood experiences in primary care, physician self-care) and families (e.g., how children respond to trauma and stress). While not specific to medical institutions, SAMHSA provides online resources that healthcare professionals may find useful, such as education about trauma-informed services, recommendations for medical professionals working with individuals with history of childhood sexual abuse, and trauma screening tools.68 Additionally, initially developed for residential programs serving homeless families, the Trauma-Informed Organizational Self-Assessment69 can be adapted for use in pediatric healthcare settings to evaluate the extent to which specific trauma-informed practices are being implemented. However, structured guidelines of how to transform pediatric medical institutions into trauma-informed care systems do not yet exist. Given the challenge of making large-scale changes in healthcare networks, it may be best to apply an established approach to trauma-informed care training: The Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Framework for Spread.70 The purpose of this model is to help institutions shift from “common” to “best” practices (i.e., spreading best practices). In the case of trauma-informed care, this means infusing understanding and application of trauma-informed practices throughout the healthcare network. This framework includes three primary steps: 1) prepare for the spread, 2) establish an aim for spread, and 3) develop, execute, and refine a spread plan. Using the Framework for Spread, during each step, institutions create action items and identify and answer questions that address barriers or challenges to fully integrating a trauma-informed approach to healthcare. For example, in step 1 (prepare for spread), leaders are selected and administration is approached; questions about the perceived value of trauma-informed care practices and resources for training and implementing a trauma-informed approach are addressed. In step 2 (establishing aim for spread), the network decides where to start training and set goals for training; questions of training modality and participants are answered. In step 3 (develop, execute, and refine a spread plan), decision-makers are identified, training begins, feedback is collected; questions about attitudes towards trauma-informed care, and barriers and successes in implementing the training are discussed. See Table 2 examples of actions and questions for each step in transforming a network to implement a trauma-informed care approach to medical care.

Table 2.

Framework for transforming healthcare networks to implement trauma-informed care practices

| Prepare for spread |

|

|

| Actions: |

| • Engage executive leadership in supporting trauma-informed care initiatives (e.g., provide information on patient and staff outcomes) |

| • Designate leaders to champion the desired changes by creating partnerships with departments and/or clinical group |

| • Initiate early communication across the institution about why trauma-informed care is important |

|

|

| Questions: |

| • Does this institution value trauma-informed care? |

| • Is the institution ready for this shift in care? |

| • What resources are available to support training and implementation of trauma-informed care? |

| • What resources are available to support staff in self-care? |

| • Does the institution have the expertise in-house to lead trauma-informed care training or are external consultants needed? |

|

|

| Establish an aim for spread |

|

|

| Actions: |

| • Determine which departments/clinic groups will first receive training |

| • Define goals (e.g., 90% of direct care staff will complete a trauma-informed care seminar; staff confidence in preventing/minimizing medical traumatic stress will increase; patient satisfaction scores will increase; staff job satisfaction will increase) |

| • Set a timeline |

|

|

| Questions: |

| • What type of training will be provided? |

| • Will each training be tailored to that department/clinic or will everyone receive the same information? |

| • Will training be multi-disciplinary or discipline specific? |

| • How will the training be delivered? |

| • How will training be sustainable over time? |

| • How will goals be measured? |

|

|

| Develop, execute, and refine a spread plan |

|

|

| Actions: |

| • Determine who is/are the decision-makers about training and implementing trauma-informed care practices |

| • Plan for who will be responsible for the trauma-informed care training program once the decision is made to initiate training |

| • Identify barriers to training (e.g., no room in the lecture schedule, need for additional buy-in from leadership and providers, concerns that identifying more trauma will result in more referrals) |

| • Collect feedback/data as plan begins (e.g., is the training relevant, is more training needed, do departments support the implementation of the skills learned in the training) |

|

|

| Questions: |

| • What are the current attitudes towards trauma-informed care training? |

| • Are some trauma-informed care practices already occurring? If so, how can we build on them? |

| • How does the feedback/data suggest a need for changes in the training program? |

| • Is it best to start with one department and or should everyone be trained simultaneously? |

| • How are rotating trainees (e.g., residents) provided the training? |

| • Can cost-effectiveness be demonstrated? |

Actions for Providers and Support Staff within Pediatric Healthcare Networks

Every healthcare network employee can engage in and encourage trauma-informed care practices. Those in leadership roles can become role models or set new policies. Providers on medical teams can pursue training themselves and educate their colleagues. If providers are training others (e.g., residents, fellows), they can require training and model trauma-informed care practices. Becoming a champion within a department or team can begin change on that team. Once many individuals in the network begin to experience the value of implementing trauma-informed care practices, a more formal Framework for Spread plan can be developed.

Conclusions

Given the high prevalence and impact of trauma on pediatric patients, families, and providers, it is essential that pediatric healthcare networks integrate a trauma-informed care approach into delivery of medical care. Most medical providers do not receive training in trauma-informed care as part of their standard training and may need on-the-job training. It may be helpful to apply The Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Framework for Spread in designing and carrying out trauma-informed care training programs in pediatric medical institutions. While trauma-informed practices have the potential to improve patient care, more research is necessary to determine the effect of network-wide implementation of trauma-informed practices on patient and staff outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Mentored Career Award grant 1K23MH093618-01A1 from the National Institute of Mental Health, grant U79SSM061255 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Violence Prevention Initiative at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Each of these funders supported investigator time for preparation and review of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Niska RW, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 Emergency Department Summary. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Care of Children and Adolescents in U.S. Hospitals. US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hing E, Hall MJ, Ashman JJ, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 Outpatient Department Summary. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saxe G, Vanderbilt D, Zuckerman B. Traumatic stress in injured and ill children. PTSD Research Quarterly. 2003;14:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuber M, Shemesh E, Saxe G. Posttraumatic stress responses in children with life-threatening illness. Child Adol Psych Cl. 2003;12:195–209. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landolt MA, Vollrath M, Ribi K, Gnehm HE, Sennhauser FH. Incidence and associations of parental and child posttraumatic stress symptoms in pediatric patients. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1199–1207. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rennick JE, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, Platt R, Ritchie JA. Children's psychological responses after critical illness and exposure to invasive technology. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2002;23(3):133–144. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American journal of preventive medicine. 1998 May;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copeland W, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Gore S. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey. BMC public health. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kazak AE, Kassam-Adams N, Schneider S, Zelikovsky N, Alderfer MA, Rourke M. An integrative model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006 May;31(4):343–355. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko SJ, Ford JD, Kassam-Adams N, et al. Creating trauma-informed systems: Child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008 Aug;39(4):396–404. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration A Trauma-Informed Approach. 2014 http://www.samhsa.gov/traumajustice/traumadefinition/approach.aspx. [PubMed]

- 14.Stuber M, Schneider S, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, Saxe G. The medical traumatic stress toolkit. CNS Spectrums. 2006;11:137–142. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900010671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassam-Adams N, Marsac ML, Hildenbrand AK, Winston F. Posttraumatic stress following pediatric injury: Update on diagnosis, risk factors, and intervention. Jama Pediatr. 2013 Dec;167(12):1158–1165. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5 ed American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009 Nov 1;124(5):1411–1423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0467. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks JS, McQueen DV. Chronic disease. In: Koop CE, Pearson CE, Schwarz MR, editors. Critical Issues in Global Health. Josey-Bass; San Francisco: 2001. pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costello E, Erkanli A, Fairbank J, Angold A. The prevalence of potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002 Apr;15(2):99–112. doi: 10.1023/A:1014851823163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newacheck P, Taylor W. Childhood chronic illness prevalence, severity and impact. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;82:364–371. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslau N, Wilcox H, Storr C, Lucia V, Anthony J. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: A study of youths in urban America. Journal of Urban Health. 2004;81(4):530–544. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazak AE, Schneider S, Kassam-Adams N. Pediatric medical traumatic stress. In: Roberts MC, Steele RG, editors. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. 4th The Guilford Press; New York: 2009. pp. 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Child Traumatic Stress Network . Paper presented at the Paper presented at the Medical Traumatic Stress Working Group meeting. Philadelphia: Definition of medical traumatic stress; p. PA2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holbrook T, Hoyt D, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise M, Anderson J. Long-term posttraumatic stress disorder persists after major trauma in adolescents: New data on risk factors and functional outcome. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection and Critical Care. 2005 Apr;58(4):764–769. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000159247.48547.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zatzick D, Jurkovich G, Fan M, et al. Association between posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms and functional outcomes in adolescents followed up longitudinally after injury hospitalization. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162(7):642–648. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.7.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham-Bermann S, Seng J. Violence exposure and traumatic stress symptoms as additional predictors of health problems in high-risk children. Journal of Pediatrics. 2005 Mar;146(3):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landolt MA, Buehlmann C, Maag T, Schiestl C. Brief Report: Quality of life is impaired in pediatric burn survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(1):14–21. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landolt MA, Vollrath ME, Gnehm HE, Sennhauser FH. Post-traumatic stress impacts on quality of life in children after road traffic accidents: prospective study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;43(8):746–753. doi: 10.1080/00048670903001919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012 Jan 1;129(1):e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaffee SR, Christian CW. The biological embedding of child abuse and neglect: Implications for policy and practice: Society for Research in Child Development. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kassam-Adams N, Fleisher CL, Winston FK. Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of injured children. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009 Aug;22(4):294–302. doi: 10.1002/jts.20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kassam-Adams N, Winston FK. Predicting child PTSD: The relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD in injured children. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2004 Apr;43(4):403–411. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foa E. Psychological processes related to recovery from a trauma and an effective treatment for PTSD. In: McFarlane AC, Yehuda R, editors. Psychobiology of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. New York Academy of Sciences; New York: 1997. pp. 410–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahana S, Feeny N, Youngstrom E, Drotar D. Posttraumatic stress in youth experiencing illnesses and injuries: An exploratory meta-analysis. Traumatology. 2006;12(2):148–161. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall E, Saxe G, Stoddard F, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of children with acute burns. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006 May;31(4):403–412. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazak AE, Alderfer M, Rourke MT, Simms S, Streisand R, Grossman JR. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004 Apr-May;29(3):211–219. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margolin G, Vickerman KA. Post-traumatic stress in children and adolescents exposed to family violence: Overview and issues. Professional psychology, research and practice. 2007 Dec 1;38(6):613–619. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual review of psychology. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robins PM, Meltzer L, Zelikovsky N. The experience of secondary traumatic stress upon care providers working within a children's hospital. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2009;24(4):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hooper C, Craig J, Janvrin DR, Wetsel MA, Reimels E. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue among emergency nurses compared with nurses in other selected inpatient specialties. J Emerg Nurs. 2010 Sep;36(5):420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Figley C. Compassion fatigue: Secondary traumatic stress. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Figley C. Treating compassion fatigue. Routledge; Florence, KY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maslach C, Leiter MP. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J Appl Psychol. 2008 May;93(3):498–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Najjar N, Davis LW, Beck-Coon K, Doebbeling CC. Compassion fatigue: a review of the research to date and relevance to cancer-care providers. Journal of health psychology. 2009 Mar;14(2):267–277. doi: 10.1177/1359105308100211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: a prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009 Sep 23;302(12):1338–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Mar 5;136(5):358–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fields AI, Cuerdon TT, Brasseux CO, et al. Physician burnout in pediatric critical care medicine. Critical care medicine. 1995 Aug;23(8):1425–1429. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199508000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Committee On Hospital Care. Institute For Patient Family-Centered Care Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2012 Feb;129(2):394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. [Accessed December 3, 2014];Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress. 2009 www.HealthCareToolbox.org.

- 50.Stuber M, Schneider S, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, Saxe G. The Medical Traumatic Stress Toolkit. CNS Spectrums. 2006;11:137–142. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900010671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore KA, Coker K, DuBuisson AB, Swett B, Edwards WH. Implementing potentially better practices for improving family-centered care in neonatal intensive care units: successes and challenges. Pediatrics. 2003 Apr;111(4):e450–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson B, Abraham M, Conway J, et al. Partnering with Patients and Families to Design a Patient- and Family-Centered Health Care System. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Bethesda, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hemmelgarn AL, Glisson C, James LR. Organizational Culture and Climate: Implications for Services and Interventions Research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13(1):73–89. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hemmelgarn AL, Glisson C, Dukes D. Emergency Room Culture and the Emotional Support Component of Family-Centered Care. Children's Health Care. 2001;30(2):93–110. 2001/06/01. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. Jama. 2003 Apr 16;289(15):1969–1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleuren M, Wiefferink K, Paulussen T. Determinants of innovation within health care organizations: Literature review and Delphi study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2004;16(2):107–123. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh030. 2004-04-01 00:00:00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alisic E, Conroy R, Magyar J, Babl FE, O'Donnell ML. Psychosocial care for seriously injured children and their families: A qualitative study among Emergency Department nurses and physicians. Injury. 2014;45(9):1452–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laraque D, Boscarino JA, Battista A, et al. Reactions and needs of tristate-area pediatricians after the events of September 11th: implications for children's mental health services. Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5):1357–1366. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ziegler MF, Greenwald MH, DeGuzman MA, Simon HK. Posttraumatic stress responses in children: awareness and practice among a sample of pediatric emergency care providers. Pediatrics. 2005 May;115(5):1261–1267. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banh MK, Saxe G, Mangione T, Horton NJ. Physician-reported practice of managing childhood posttraumatic stress in pediatric primary care. General hospital psychiatry. 2008;30(6):536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zatzick DF, Jurkovich G, Wang J, Rivara FP. Variability in the characteristics and quality of care for injured youth treated at trauma centers. The Journal of pediatrics. 2011 Dec;159(6):1012–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harris M, Fallot RD. Using trauma theory to design service systems. Vol 89. Josey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bloom SL, Bennington-Davis M, Farragher B, McCorkle D, Nice-Martin K, Wellbank K. Multiple opportunities for creating sanctuary. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2003;74(2):173–190. doi: 10.1023/a:1021359828022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rivard JC, Bloom SL, McCorkle D, Abramovitz R. Preliminary results of a study examining the implementation and effects of a trauma recovery framework for youths in residential treatment. Therapeutic Community: The International Journal for Therapeutic and Supportive Organizations. 2005;26(1):83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kassam-Adams N, Rzucidlo S, Campbell M, et al. Nurses' views and current practice of trauma-informed pediatric nursing care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ward-Begnoche WL, Aitken ME, Liggin R, et al. Emergency department screening for risk for post-traumatic stress disorder among injured children. Injury Prevention. 2006;12(5):323–326. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.011965. 06/05/accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corbin T, Purtle J, Rich L, et al. The prevalence of trauma and childhood adversity in an urban, hospital-based violence intervention program. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2013;24(3):1021–1030. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. [Accessed December 5, 2014];Trauma. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/trauma#RESOURCES.

- 69.Guarino K, Soares P, Konnath K, Clervil R, Bassuk E. Trauma-Informed Organizational Toolkit. Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Daniels Fund, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation; Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Massoud MR, Nielsen GA, Nolan K, Nolan T, Schall MW, Sevin CA. Framework for spread: From local improvements to system-wide change. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2006. [Google Scholar]