Abstract

Prior research shows that violence is associated with sexual risk behavior, but little is known about the relation between community violence (i.e., violence that is witnessed or experienced in one's neighborhood) and sexual risk behavior. To better understand contextual influences on HIV risk behavior, we asked 508 adult patients attending a publicly-funded STI clinic in the U.S. (54% male, Mage = 27.93, 68% African American) who were participating in a larger trial to complete a survey assessing exposure to community violence, sexual risk behavior, and potential mediators of the community violence-sexual risk behavior relation (i.e., mental health, substance use, and experiencing intimate partner violence). A separate sample of participants from the same trial completed measures of sexual behavior norms, which were aggregated to create measures of census tract sexual behavior norms. Data analyses controlling for socioeconomic status revealed that higher levels of community violence were associated with more sexual partners for men and with more episodes of unprotected sex with non-steady partners for women. For both men and women, substance use and mental health mediated the community violence-sexual risk behavior relation; in addition, for men only, experiencing intimate partner violence also mediated this relation. These results confirm that, for individuals living in communities with high levels of violence, sexual risk reduction interventions need to address intimate partner violence, substance use, and mental health to be optimally effective.

Keywords: community violence, sexual risk behavior, mental health, substance use, partner violence, sexual behavior norms

INTRODUCTION

STIs and HIV are major public health problems. In the U. S., nearly 1.2 million people are living with HIV and 50,000 are newly infected each year (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; 2013), a rate that has remained stable for the past decade (Hall et al., 2008). There are an estimated 20 million new STIs in the U.S. each year; rates of chlamydia and syphilis have increased over the past decade, whereas rates of gonorrhea have been relatively stable over this timeframe (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015; Owusu-Edusei et al., 2013). The lifetime direct medical costs of STIs acquired in the US in a single year have been estimated at $15.6 billion, with HIV accounting for most of that cost (Owusu-Edusei et al., 2013).

To reduce rates of STIs and HIV, researchers have long sought to understand the correlates of sexual risk behaviors and health outcomes; the focus of much of this research has been on individual-level risk factors (Albarracin, Johnson, Fishbein, & Muellerleile, 2001; Fisher & Fisher, 2000). However, such individual-focused research and theoretical models neglect the important influence of social and contextual factors (Johnson et al., 2010).

More recently, the effect that neighborhood-level contextual factors have on sexual health and STIs has been increasingly recognized. A main focus of this neighborhood-level research has been to understand how neighborhood socioeconomic (SES) disadvantage is associated with sexual health. Living in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood is associated with a greater likelihood of sexual debut among adolescents (Carlson, McNulty, Bellair, & Watts, 2014; Cubbin, Santelli, Brindis, & Braveman, 2005; Voisin, Hotton, & Neilands, 2014), a greater number of sexual partners (Carlson et al., 2014), and a higher likelihood of being infected with an STI (Ford & Browning, 2014).

A second, less well-studied neighborhood-level factor that may be associated with sexual risk behavior is community violence. The interest in community-level violence as a potential correlate of sexual risk emerges from research showing that individual- and family-level violence (e.g., child maltreatment, intimate partner violence) are associated with sexual risk behavior (Coker et al., 2002; Hillis, Anda, Felitti, & Marchbanks, 2001; Senn, Carey, Vanable, Coury-Doniger, & Urban, 2006; Seth, Raiford, Robinson, Wingood, & DiClemente, 2010; Walsh, Senn, & Carey, 2012; Wilson & Widom, 2009). A small number of studies have found that greater community violence is associated with sexual risk behavior, including ever being or getting someone pregnant among adolescents (Brahmbhatt et al., 2014), more sex partners and inconsistent condom use (Walsh et al., 2012; Wilson, Woods, Emerson, & Donenberg, 2012), and engaging in more sexual risk behaviors (Brady, 2006; Voisin, 2005).

The findings on community violence and sexual risk behavior are limited by two methodological factors. First, much of the research in this area has been conducted with adolescents (e.g., Brady, 2006; Brahmbhatt et al., 2014; Kerr, Valois, Siddiqi, Vanable, & Carey, 2015; Voisin, 2005; Wilson et al., 2012); there is limited research on the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior among adults. Second, although SES, at the individual level and at the community level, is a correlate of both sexual risk behavior (Carlson et al., 2014; Cubbin et al., 2005; Ford & Browning, 2014; Voisin et al., 2014) and community violence (Ewart & Suchday, 2002; Morenoff, Sampson, & Raudenbush, 2001), research on community violence has rarely controlled for SES.

There is limited information on the pathways through which community violence may influence sexual risk behavior. Identifying these pathways is critical to understanding how to best intervene to reduce the impact of community violence on sexual risk behavior. We draw on “broken windows” theory (Wilson & Kelling, 1982) and the stress-coping model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) to propose four potential pathways through which community violence may impact sexual risk behavior: sexual behavior norms, intimate partner violence, substance use, and mental health.

Sexual behavior norms are one pathway through which community violence may lead to sexual risk behavior. The broken windows theory proposes that neighborhood physical disorder indicates that behaviors that are typically unacceptable will be tolerated in that neighborhood. Cohen et al. (2000), who found that an index of neighborhood disorder was associated with neighborhood STI rates, applied this theory to sexual risk behavior; they suggested that the deteriorated physical environment may have led to altered norms around sexual risk behavior, such that behaviors typically considered unacceptable (e.g., trading sex; multiple sexual partners) became normative in neighborhoods where there were signs that typical neighborhood controls did not apply. We propose that community violence, which is highly correlated with neighborhood disorder (Ewart & Suchday, 2002), signals to neighborhood residents that typical norms around unacceptable behavior do not apply in their neighborhood, leading to altered sexual behavior norms among residents.

Neighborhood factors have been associated with sexual behavior norms; for example, socioeconomic disadvantage has been associated with more permissive sexual behavior norms (Browning & Burrington, 2006). Further, studies have found that neighborhood norms around sexual behavior are associated with greater likelihood of initiating sex, engaging in casual sex, and having more sexual partners among adolescents (Warner, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2011). In one of the few studies to statistically test potential mediators of the community violence-sexual risk behavior relation, negative peer attitudes about safer sex mediated this relation in adolescents (Voisin et al., 2014).

Intimate partner violence is a second pathway through which community violence may lead to sexual risk behavior. Further extending the broken windows theory, we propose that community violence sends a message to residents that violence is acceptable, leading to higher rates of intimate partner violence. Indeed, research shows that higher rates of community violence are associated with higher rates of intimate partner violence (Beyer, Wallis, & Hamberger, 2015; Raghavan, Mennerich, Sexton, & James, 2006; Reed et al., 2009; Stueve & O'Donnell, 2008). Further, partner violence is associated with sexual risk behavior, including more sexual partners and inconsistent condom use, as well as with a greater likelihood of STI and HIV infection (Hess et al., 2012; Mittal, Senn, & Carey, 2011; Phillips et al., 2014; Seth, DiClemente, & Lovvorn, 2013; Seth et al., 2010). Although partner violence has not been assessed as a potential mediator of the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior, given its association with both of these variables, it is a plausible mechanism.

Substance use is a third pathway through which community violence may lead to sexual risk behavior. The stress-coping model suggests that people often engage in health-compromising behaviors in order to reduce or manage negative affect associated with stressors; substance use, in particular, is a well-known emotion-focused coping strategy in the face of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Wills & Shiffman, 1985). Thus, it is plausible that the chronic, unavoidable stressor of community violence leads to substance use. Higher rates of community violence are associated with alcohol and drug use (Kliewer & Zaharakis, 2013; Mrug & Windle, 2009; Reboussin, Green, Milam, Furr-Holden, & Ialongo, 2014; Wright, Fagan, & Pinchevsky, 2013; Zinzow et al., 2009). Substance use, in turn, may lead to sexual risk behavior (Colfax et al., 2004; Cook & Clark, 2005; Cooper, 2006).

Mental health is a fourth pathway through which community violence may lead to sexual risk behavior. The stressor of community violence may lead to mental health problems; mental health problems may then lead to increased sexual risk behavior (Carey, Carey, & Kalichman, 1997). There is evidence that community violence is associated with mental health problems, including depression, PTSD, and psychological distress (Clark et al., 2008; Curry, Latkin, & Davey-Rothwell, 2008; Scarpa et al., 2002; Slopen, Fitzamurice, Williams, & Gilman, 2012; Wilson & Rosenthal, 2003; Zinzow et al., 2009). Mental health problems, in turn, have been associated with sexual risk behavior (DiClemente et al., 2001; Hutton, Lyketsos, Zenilman, Thompson, & Erbelding, 2004; Hutton et al., 2001; Khan et al., 2009; Lehrer, Shrier, Gortmaker, & Buka, 2006). In one of the few studies to assess mediators of the community violence-sexual risk behavior relation, among adolescent males, PTSD mediated the relation between community violence and sexual debut (Voisin et al., 2014).

The purpose of the present study was threefold: (1) to determine whether the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior, previously documented primarily in adolescent samples, would also be found in adults; (2) to investigate whether the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior remained after controlling for individual and census tract SES; and (3) to test potential mediating mechanisms through which community violence may lead to sexual risk behavior, including sexual behavior norms, intimate partner violence, mental health, and substance use. Because studies have found sex differences in the relation between neighborhood factors and sexual risk behavior (e.g., Cubbin et al., 2005; Voisin et al., 2014), we investigated associations separately by sex.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were patients attending a publicly-funded STI clinic in the U.S., who completed a baseline survey as part of a randomized controlled trial (Carey et al., 2013) to assess the effects of a brief, video-based intervention on sexual risk behavior. Half (N = 508) of participants in the trial were randomly assigned to complete a detailed general health behavior survey, which included questions about community violence, intimate partner violence, substance use, mental health, and recent sexual behavior; these participants are included in the present analyses.

The other half (N = 502) of participants in the main trial were randomly assigned to complete a detailed survey about sexual health knowledge, attitudes, sexual behavior norms, skills, and behaviors. Responses to the sexual behavior norms items from this half of the sample are used in the present study. These responses were aggregated at the census tract level. Thus, these participants do not contribute individual-level data, but their responses were used to create a measure of census tract norms for sexual behavior.

The analytic sample consisted of the 508 patients who completed the general health survey (54% male, Mage = 27.93, SDage = 9.03, 68% African American, 18% White, 8% mixed/multiracial, 8% Latino, 87% heterosexual). Participants who provided the census tract sexual behavior norms data did not differ significantly in terms of demographics or sexual risk behavior from the analytic sample (Carey et al., 2015).

Procedure

Clinic patients were called from the waiting room by a trained research assistant (RA), who escorted them to a private exam room and asked if they would be willing to answer a few questions to determine their eligibility for a study being conducted at the clinic. Participants who verbally consented to screening were asked a series of questions to determine eligibility (i.e., age 16 or older; engaged in sexual risk behavior in the past 3 months). The RA explained the study to eligible patients; those who chose to participate provided written, informed consent. Out of 1322 patients who were eligible, 1010 (76%) agreed to participate in the study and completed the survey.

Participants provided their address and completed a computerized survey assessing demographics, health behaviors, and exposure to violence. Survey completion took ~45 minutes. Then participants watched one of two video-based interventions and were reimbursed $20 for their time. All procedures were approved by the IRBs of the participating institutions.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported their sex, age, race, income (1 = less than $15,000 to 4 = more than $45,000), education (1 = 8th grade or less to 6 = graduated from college), and employment (recoded as unemployed vs. employed part- or full-time). Income, education, and employment were used to create a latent individual-level SES variable.

Census tract SES

We determined participants’ census tract based on the home address they provided. Data from the 2010 U.S. Census were used to determine census tract SES. Measures of census tract SES included: (1) per capita income in the census tract and (2) percentage of individuals with a college education in the census tract. These variables served as indicators of a latent census tract SES construct.

Community violence

Participants completed the City Stress Inventory (Ewart & Suchday, 2002), which assesses both neighborhood disorder and neighborhood violence. Participants were instructed to think about things that happened in the neighborhoods where they lived during the past year. Five items from the neighborhood violence subscale (e.g., “In the past year, how often was a family member stabbed or shot,” rated on a scale from 0 = never to 3 = often) were used as indicators of a latent community violence construct.

Sexual behavior norms

Participants who completed the sexual health survey (i.e., those who were not part of the analytic sample) completed measures of perceived descriptive norms around condom use and having multiple partners. Participants were asked to report: (1) how often men in their community used condoms for vaginal or anal sex with non-steady partners; and (2) how often women in their community used condoms for vaginal or anal sex with non-steady partners. Responses were on a 5-point scale from never to always; these items were reverse-coded such that higher scores indicated norms favoring unprotected sex. Participants were also asked to report: (1) how many partners the typical man (their age) in their community had in the past 3 months; and (2) how many partners the typical woman (their age) in their community had in the past 3 months (response options were 0, 1, 2, 3-4, 5 or more).

Response options were aggregated for census tracts with at least three participants (census tracts averaged 7.65 participants who completed the sexual health survey, SD = 4.30). These aggregate norms were treated as manifest variables representing census tract condom use norms and multiple partner norms. Because norms for sexual behavior differ by sex (Lewis, Lee, Patrick, & Fossos, 2007; Sprecher, Treger, & Sakaluk, 2013), we used norms for women in the women's model and norms for men in the men's model. We included separate variables for condom use norms and multiple partner norms.

Intimate partner violence

Participants were asked whether they had been hit, kicked, punched, or otherwise hurt by a sexual partner within the past year (adapted from Feldhaus et al., 1997). If participants responded, “yes” they were considered to have experienced recent IPV.

Substance use

A latent alcohol use construct was created based on responses to three items from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Zhou, 2005; Reinert & Allen, 2007), which assesses frequency of alcohol consumption in the past year, typical number of drinks per day (on days when drinking), and frequency of binge drinking. The 10 items from the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Skinner, 1982) were averaged into three parcels based on factor loadings; these three parcels served as indicators of a latent drug use construct.

Mental health

Mental health was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (PHQ-4) (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, & Lowe, 2009). Participants responded to four items assessing frequency of symptoms of depression and anxiety over the last 2 weeks, rated on a 4-point scale from “not at all” to “nearly every day.” These four items served as indicators of a latent construct representing depression and anxiety.

Sexual behavior

Participants responded to two items asking about the number of men and the number of women with whom they had sex in the past 3 months. Responses were summed to determine the total number of sexual partners in the past 3 months. Participants were also asked to report the number of times they had vaginal sex and the number of times they had anal sex with a steady partner and with non-steady partners. For each of those items, they were then asked to report how many times a condom was used. From these items, we calculated: (1) the total number of sexual partners, (2) the number of episodes of unprotected sex with a steady partner, and (3) the number of episodes of unprotected sex with non-steady partner(s). These items were natural-log transformed.

Data Analysis

Missing data rates ranged from 0% to 35% for the aggregated risky sexual norms variable (this variable required ≥ 3 participants in a census tract). Overall, for variables reported by participants, less than 4% of data was missing.

We used multiple imputation (MI) to replace missing values (Rubin, 1996; Schafer, 1997). MI is a method for dealing with missing data that avoids biases associated with using only complete cases or with single imputations (Schafer, 1999). We imputed 100 datasets (Graham, Olchowski, & Gilreath, 2007) in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2013). All study variables were included in the imputation, which included sex as a grouping variable. Analyses were conducted with all 100 datasets, and parameter estimates were pooled using the imputation algorithms in Mplus 7.

The primary study analyses were conducted using structural equation modeling, allowing us to test both direct and indirect associations of community violence with sexual risk behavior. Community violence, individual-level SES, census tract-level SES, depression/anxiety, alcohol use, and drug use were all represented as latent constructs with between two and five indicators each (as described in the Measures section), whereas IPV, multiple partner norms, condom use norms, number of partners, unprotected sex with main partners, and unprotected sex with non-steady partners were represented as manifest variables. Latent constructs were identified by fixing variance at 1 (Little, 2013).

Preliminary steps included (1) testing a measurement model to assure our latent constructs were adequate representations and that these constructs were invariant for men and women, (2) fitting a basic model to test whether levels of community violence predicted sexual risk outcomes for men and women, and (3) fitting a slightly more complex model to test whether levels of community violence predicted sexual risk outcomes after accounting for individual-level and census tract-level SES. In our final structural model, which tested the hypothesized mediators, directional paths led from community violence to the six hypothesized mediators (i.e., depression/anxiety, alcohol use, drug use, intimate partner violence, multiple partner norms, condom use norms) and the sexual risk outcomes and from the six hypothesized mediators to the sexual risk outcomes, in line with our hypotheses. Additionally, in all models, directional paths led from demographic variables (including individual-level SES, census tract-level SES, age, White race, and mixed race) to all constructs in order to control for these variables. Community violence, individual-level SES, and census tract-level SES were allowed to correlate, as were the six mediating variables and the sexual risk outcomes.

Models were fit with a robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimator in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2013). Model fit was assessed using traditional fit indices, including the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990); the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973); and the misfit measure known as the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Kline, 2011). Good fit is indicated by CFI and TLI values greater than .95 and RMSEA values less than .05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2011). Given our use of MI in models including covariates, these fit indices were averages over 100 imputations. We report standardized coefficients and standard errors.

When testing mediation, we calculated 95% confidence intervals using the distribution-of-the-product method in RMediation (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). This is recommended given the non-normal distribution of indirect effects. For indirect effects, we report unstandardized coefficients and 95% confidence intervals as well as standardized coefficients.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics. Exposure to community violence was common: during the past year, 31% of participants reported that a family member had been attacked or beaten in their neighborhood, 29% that a family member had been stabbed or shot, 47% that a friend had been stabbed or shot, 63% that a family member had been stopped and questioned by the police, and 46% that a friend had been robbed or mugged. The sample was predominantly socioeconomically disadvantaged, with at least half of participants reporting an income <$15,000/year (53%), a high school or less education (63%), and current unemployment (50%). Participants also lived in socioeconomically disadvantaged census tracts, with a median per capita income of $14,267 per year. The median percentage of college graduates in these census tracts was 13%.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Entire Sample | Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 508 | 236 | 272 |

| Demographics | M (SD) / % | M (SD) / % | M (SD) / % |

| Male | 54% | -- | -- |

| Age (in years) | 27.9 (9.0) | 27.1 (8.5) | 28.6 (9.4) |

| Black | 68% | 67% | 70% |

| White | 18% | 19% | 17% |

| Mixed | 8% | 8% | 9% |

| Latino | 8% | 10% | 7% |

| Sexual minority | 13% | 19% | 7% |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Income < $15,000/year | 53% | 58% | 48% |

| High school or less education | 63% | 56% | 68% |

| Employed full- or part-time | 50% | 52% | 48% |

| Census tract-level SES | |||

| Per capita income | $16,327 ($7,459) | $15,853 ($6,589) | $16,744 ($8,138) |

| Percent college graduate | 17% | 17% | 16% |

| Community violence | |||

| Exposure to violence (M, range 0-3) | 0.7 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.8) |

| Family member attacked or beaten | 0.5 (0.9) / 31% | 0.5 (0.8) / 29% | 0.5 (0.9) / 32% |

| Family member stabbed or shot | 0.5 (0.8) / 29% | 0.4 (0.8) / 30% | 0.5 (0.9) / 29% |

| Friend stabbed or shot | 0.8 (1.0) / 48% | 0.8 (1.0) / 47% | 0.8 (1.0) / 49% |

| Family member stopped and questioned by police | 1.2 (1.1) / 63% | 1.0 (1.0) / 57% | 1.4 (1.1) / 68% |

| Friend robbed or mugged | 0.7 (0.9) / 46% | 0.6 (0.8) / 44% | 0.8 (1.0) / 48% |

| Hypothesized mediators | |||

| PHQ (M, range 0-3) | 0.9 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.7) |

| DAST (sum, range 0-10) | 1.4 (2.2) | 1.4 (2.3) | 1.5 (2.2) |

| Alcohol use frequency (past year) | |||

| Never | 13% | 15% | 12% |

| Once a month or less | 27% | 32% | 24% |

| 2-4 times per month | 31% | 27% | 35% |

| 2-3 times per week | 19% | 20% | 18% |

| 4 or more times per week | 10% | 6% | 13% |

| Drinks per drinking day (past year) | |||

| 1 or 2 | 54% | 58% | 50% |

| 3 or 4 | 26% | 26% | 27% |

| 5 or 6 | 12% | 11% | 13% |

| 7 to 9 | 5% | 3% | 6% |

| 10 or more | 3% | 2% | 4% |

| Binge drinking frequency (past year) | |||

| Never | 36% | 39% | 34% |

| Less than monthly | 30% | 31% | 28% |

| Monthly | 17% | 14% | 19% |

| Weekly | 15% | 14% | 16% |

| Daily or almost daily | 3% | 2% | 4% |

| Partner norms (census tract aggregate, range 0-4) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.6) |

| Condom use norms (census tract aggregate, range 0-4) | 1.9 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) |

| Intimate partner violence (past year) | 26% | 28% | 23% |

| Sexual risk behaviors | |||

| Number of sexual partners (past 3 months) | 2.6 (1.9) | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.8 (1.9) |

| Unprotected sex with main partners (past 3 months) | 13.8 (20.3) | 13.1 (18.5) | 14.4 (21.7) |

| Unprotected sex with outside partners (past 3 months) | 2.2 (3.3) | 1.7 (2.8) | 2.7 (3.7) |

Symptoms of depression and anxiety were reported frequently, with 23% of participants exceeding the PHQ cutoff for depression and 30% exceeding the cutoff for anxiety. The majority (87%) of participants reported drinking alcohol in the past year, and 64% of participants reported consuming five or more drinks on at least one occasion in the past year. Based on AUDIT-C scores, 55% qualified as hazardous drinkers. In terms of drug use, 20% of participants (n = 103) exceeded a DAST score of 3, indicating at least a moderate level of problems related to drug abuse. A quarter of participants had recent experiences of IPV. The aggregated descriptive norms variables for numbers of partners had averages of 2.9 for men (SD = 0.5) and 2.7 (SD = 0.5) for women. Aggregated condom use descriptive norms were 1.9 for men (SD = 0.4) and 1.9 for women (SD = 0.4); this indicated perceptions that others used condoms “about half the time.”

Participants reported an average of 2.6 sexual partners in the past 3 months (SD = 1.9), 13.8 acts of unprotected sex with main partners (SD = 20.3), and 2.2 acts of unprotected sex with non-steady partners (SD = 3.3). Seven percent of participants reported having a same-sex partner in the past 3 months (6.6% of men, n = 18; 8.1% of women, n = 19). Among those who completed the sexual health survey (i.e., were not part of the analytic sample), 1% reported being in a mutually monogamous relationship for the past 3 months.

Measurement Model

We first tested a multigroup measurement model, which included the six constructs represented as latent variables (community violence, individual-level SES, census tract-level SES, poor mental health, alcohol use, and drug use). We began with a measurement model where factor loadings, intercepts, and thresholds were freely estimated for women and men, and compared this model to models with equality constraints on the factor loadings (i.e., metric invariance) and intercepts/thresholds (i.e., scalar invariance) for males and females.

Fit indices supported full metric invariance and partial scalar invariance and showed the measurement model to be a good fit to the data, fit for model without constraints: χ2(308, Ns = 236, 272) = 413.77, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04; fit for model with constraints: χ2(146, Ns = 236, 272) = 443.27, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.03. Only two of 20 intercepts/thresholds differed for men and women; this level of invariance gave us confidence in proceeding with our structural models (Byrne, Shavelson, & Muthén, 1989). All factor loadings were high (βs > .62, ps < .0001) and no indicators cross-loaded.

Associations of Community Violence and Socioeconomic Status with Sexual Risk Behavior

Community violence and sexual risk behavior

We next tested associations between community violence and the sexual risk behaviors controlling for demographic covariates in a multigroup structural model. This model was a good fit to the data, χ2(75, Ns = 236, 272) = 119.01, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.05. Controlling for demographics, for women, community violence had a marginally significant positive association with unprotected sex with non-steady partners, β = 0.15 (0.07), p < .10. This indicated that women who reported more community violence had engaged in more acts of unprotected sex with non-steady partners during the past 3 months. There was no significant association between community violence and the number of sexual partners, β = 0.08 (0.07), p = .28, or unprotected sex with main partners, β = −0.06 (0.08), p = .45. For men, community violence had a significant positive association with the number of sexual partners, β = 0.20 (0.06), p < .01. This indicated that men who reported more community violence had engaged in sex with more partners during the past 3 months. There was no significant association between community violence and unprotected sex with main partners, β = −0.04 (0.07), p = .58, or non-steady partners, β = 0.09 (0.07), p = .24.

Community violence, SES, and sexual risk behavior

We next added the two SES constructs to our structural model to test whether associations between community violence and risk behavior remained after accounting for SES. This model was also a good fit to the data, χ2(172, Ns = 236, 272) = 210.28, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.03. After accounting for SES, for women, there was a significant, positive association between community violence and unprotected sex with non-steady partners, β = 0.24 (0.11), p < .05. This indicated that women who reported more experiences with community violence also reported engaging in more unprotected sex with non-steady partners. There were still no significant associations between community violence and number of partners, β = 0.09 (0.08), p = .28, or unprotected sex with main partners, β = −0.04 (0.11), p = .69.

For men, after accounting for SES, the positive association between community violence and number of partners remained, β = 0.23 (0.07), p = .001, indicating that men in more violent communities reported more sexual partners. There were still no significant associations between community violence and unprotected sex with main partners, β = −0.03 (0.09), p = .72, or non-steady partners, β = 0.10 (0.08), p = .81.

Given that unprotected sex with main partners was not associated with community violence or SES for either women or men, this variable was dropped from further analyses.

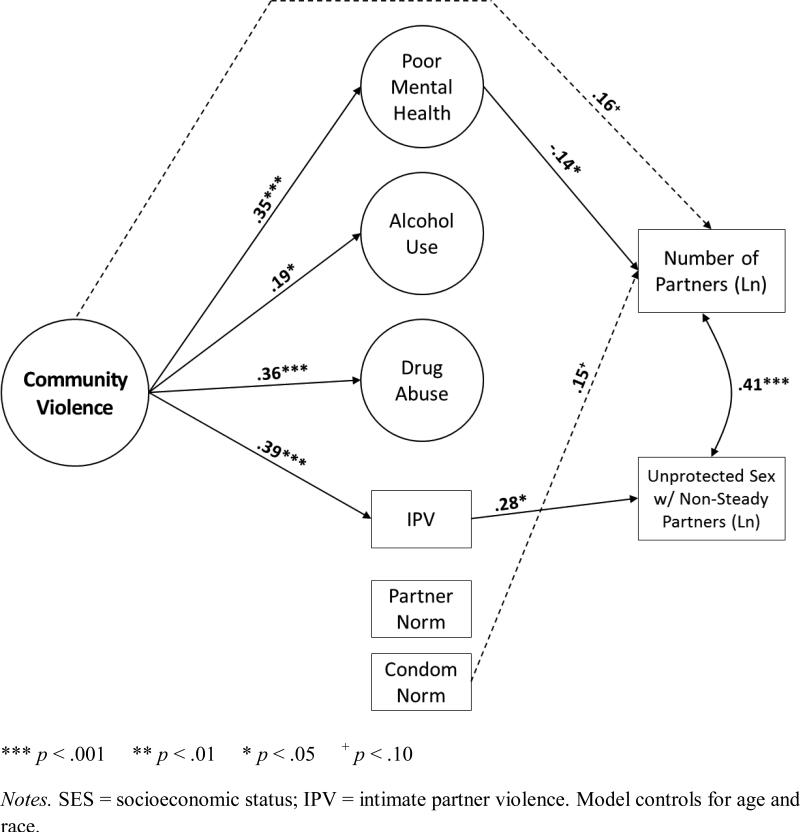

Mediation Model

The final structural model, which included community violence, the six mediating variables, two sexual behavior measures (i.e., number of partners, unprotected sex with non-steady partners), and demographic covariates (including SES) fit the data well, χ2(310, Ns = 236, 272) = 681.14, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.03. For women (Fig. 1), this model explained 25% of the variance in number of partners (p < .001) and 17% of the variance in unprotected sex with non-steady partners (p < .05). For men (Fig. 2), this model explained 11% of the variance in number of partners (p < .01) and 15% of the variance in unprotected sex with non-steady partners (p < .01).

Figure 1.

Full mediation model linking community violence and sexual risk behavior among women attending a sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic (N = 236). The multigroup structural equation model fit the data well, χ2(574) = 681.14, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .98, TLI = .97 (average over 100 imputations).

Figure 2.

Full mediation model linking community violence and sexual risk behavior among men attending a sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic (N = 272). The multigroup structural equation model fit the data well, χ2(574) = 681.14, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .98, TLI = .97 (average over 100 imputations).

Indirect associations between community violence and sexual risk behavior for women

For women, controlling for demographics and individual-level and census tract-level SES, community violence was positively associated with poor mental health, β = 0.23 (0.11), p < .05, alcohol use, β = 0.23 (0.10), p < .05, drug use, β = 0.25 (0.09), p < .01, and IPV, β = 0.30 (0.11), p < .01. This indicated that women reporting more exposure to community violence experienced higher levels of depression/anxiety, consumed more alcohol, reported higher levels of drug abuse, and were more likely to have experienced partner violence in the past 3 months. There were no significant associations between community violence and multiple partner norms or condom use norms (aggregated to the census tract level). Women who reported higher levels of depression/anxiety also reported more unprotected sex with non-steady partners, β = 0.25 (0.11), p < .05. Additionally, women who reported higher levels of alcohol use or drug use reported more sexual partners, β = 0.21 (0.07), p < .01 and β = 0.33 (0.06), p < .001, respectively. Finally, women living in census tracts with descriptive norms favoring multiple partners for women reported more unprotected sex with non-steady partners, β = 0.21 (0.10), p < .05.

Tests of mediation showed a significant indirect effect of community violence on number of partners via alcohol use, B = 0.02 (0.01), 95% CI = [0.001,0.05], p < .05, β = 0.05, and drug use, B = 0.03 (0.01), 95% CI = [0.01,0.06], p < .01, β = 0.09. More exposure to community violence was associated with higher levels of substance use; higher levels of substance use were, in turn, associated with having more sexual partners. Additionally, there was a marginally significant indirect effect of community violence on unprotected sex with non-steady partners via poor mental health, B = 0.04 (0.03), 95% CI = [−0.002,0.10], p < .10, β = 0.06. More exposure to community violence was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety, which were associated with more engagement in unprotected sex with non-steady partners. The total effect of community violence on unprotected sex with non-steady partners was also significant, β = 0.25 (0.12), p < .05.

Indirect associations between community violence and sexual risk behavior for men

For men, controlling for demographics and individual-level and census tract-level SES, community violence was positively associated with poor mental health, β = 0.35 (0.09), p < .001, alcohol use, β = 0.19 (0.09), p < .05, drug use, β = 0.36 (0.08), p < .001, and IPV, β = 0.39 (0.10), p < .001. This indicated that men reporting more exposure to community violence experienced higher levels of depression/anxiety, consumed more alcohol, reported higher levels of drug abuse, and were more likely to have experienced partner violence in the past 3 months. There were no significant associations between community violence and multiple partner norms or condom use norms (aggregated to the census tract level). Men who reported higher levels of depression/anxiety reported fewer sexual partners, β = −0.14 (0.07), p < .05. Additionally, men who had experienced partner violence engaged in more unprotected sex with non-steady partners, β = 0.28 (0.07), p < .05.

Tests of mediation showed a significant indirect effect of community violence on number of partners via poor mental health, B = −0.02 (0.01), 95% CI = [−0.03,0.00], p = .05, β = −0.05. More exposure to community violence was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety; contrary to expectations, these higher levels of depression and anxiety were, in turn, associated with having fewer sexual partners. There was a marginally significant indirect effect of community violence on number of sexual partners via a combination of alcohol and drug use, B = 0.02 (0.01), 95% CI = [0.00,0.03], p = .08, β = 0.04; neither of these indirect effects reached significance independently. Men who reported more exposure to community violence engaged in higher levels of alcohol and drug use; although neither alcohol nor drug use was significantly associated with number of sexual partners, when combined, there was a trend toward a positive association between substance use and number of sexual partners. After including all hypothesized mediators in the model, a marginally significant direct effect of community violence and number of partners remained, β = 0.16 (0.09), p = .06. The total effect of community violence on number of partners was significant for men, β = 0.22 (0.07), p = .001. There was also a significant indirect effect of community violence on unprotected sex with non-steady partners via IPV, B = 0.07 (0.04), 95% CI = [0.01,0.15], p < .05, β = 0.11. More exposure to community violence was associated with an increased likelihood of having experienced partner violence, which was, in turn, associated with more engagement in unprotected sex.

DISCUSSION

Several significant findings emerged from this research. First, community violence was associated with sexual risk behavior in a sample of adult men and women attending an urban STI clinic in the U.S. The association between community violence and sexual risk behavior remained even after controlling for individual and census tract-level SES. Second, associations differed for men and women; for men, higher rates of community violence were associated with reporting more partners in the past three months whereas, for women, higher rates of community violence were associated with reporting more episodes of unprotected sex with a non-steady partner. Overall, these findings corroborate prior research that has found a relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior among adolescents (Brady, 2006; Brahmbhatt et al., 2014; Voisin, 2005; Wilson et al., 2012). The current research builds on prior work by (1) extending this finding to an adult population; (2) controlling for individual and census tract-level SES; and (3) investigating associations separately by sex.

Several variables mediated the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior, but the mediating variables differed by sex and by sexual behavior outcome. For both men and women, substance use mediated the relation between community violence and the number of sexual partners in the past three months, although the indirect effect was only marginally significant for men. This finding provides support for the stress-coping model, which suggests that, in an attempt to cope with chronic and uncontrollable stressful circumstances (i.e., living in a chronically violent community), individuals may engage in substance use to temporarily relieve their stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Wills & Shiffman, 1985). Substance use may then lead to sexual risk behavior (Cook & Clark, 2005; Cooper, 2006).

Mental health also mediated the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior, but the pattern of associations differed by sex, and the indirect effect for women was only marginally significant. For both women and men, community violence led to higher rates of anxiety and depression. For women, higher rates of anxiety and depression were associated with more episodes of unprotected sex with a non-steady partner. Women may engage in unprotected sex, in part, to relieve the negative emotions associated with anxiety and depression. In addition, negative affect may undermine their ability to negotiate safer sex with partners. Among men, however, anxiety and depression was associated with fewer sexual partners. This finding was unexpected but it may reflect the fact that depression often involves a decreased interest or pleasure in formerly enjoyable activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), such as sexual activity. Anxiety/depression may play a different role in sexual risk behavior depending on sex. Given that men often initiate sex, negative affect may undermine this behavior; in contrast, for women, negative affect may weaken their ability to negotiate safer sex with assertive male partners.

Finally, for men, IPV mediated the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior. Greater rates of community violence were associated with higher reported rates of IPV, a finding that is consistent with previous research (Beyer et al., 2015; Raghavan et al., 2006; Reed et al., 2009; Stueve & O'Donnell, 2008). However, much of this prior research has focused on male perpetrators and female victims of IPV. This current study was unique in that community violence was associated with higher rates of male IPV victimization. Relationships characterized by IPV may include violent acts by both partners (Straus & Ramirez, 2007; Swahn, Alemdar, & Whitaker, 2010; Whitaker, Haileyesus, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007); the items we used to assess IPV may be capturing this reciprocal violence. Alternatively, these items may be capturing participants’ partners’ attempts to defend themselves from violence by the participant. Unfortunately, the items we used asked only about IPV victimization, not perpetration, and did not specify that a person's attempts to defend him/herself from violence should not be included in responses. Additionally, men who have sex with men (MSM) were included in our study, potentially clouding interpretation of results, as power and violence may differ in MSM's relationships. However, when models were run excluding men who reported having sex with men, the indirect effect through IPV remained significant.1 Further work is needed to better determine the circumstances characterizing the IPV reported by these men.

Contrary to our hypotheses, norms (aggregated to the census tract level) were unrelated to community violence and were largely unrelated to the sexual behavior outcomes. This finding was surprising, given that norms predict intentions and health behaviors, including sexual risk behavior (Albarracin et al., 2001; Eisenberg, Toumbourou, Catalano, & Hemphill, 2014; Rivis & Sheeran, 2003). Several factors may explain the lack of association between norms and community violence or sexual risk behavior. First, we examined descriptive norms (i.e., what people actually do) whereas other research has examined injunctive norms (i.e., what people think others expect them to do) (Borsari & Carey, 2003). Injunctive norms may be a better predictor of behavior than descriptive norms. Second, past research has typically utilized individual perceptions of norms, although in a few cases norms have been aggregated to neighborhood levels (Musick, Seltzer, & Schwartz, 2008; Warner et al., 2011). Norms reflect group expectations for behavior, and the aggregation of norms to the census tract level reflects group expectations, rather than individual attitudes about what others think; however, it may be that individual attitudes, while not reflecting group expectations, are better predictors of actual behavior than the normative climate we assessed in this study. Third, some census tracts may not have had enough participants to accurately estimate norms. Fourth, we used census tract as a proxy for neighborhood to create our norms variables. However, census tracts can be large and heterogeneous; in addition, census tract boundaries do not directly map onto residents’ perceptions of neighborhood boundaries. These limitations of the census tract aggregated measures may, in part, explain the lack of association between the partner norms and condom use norms variables (aggregated to the census tract level) and the other variables in the model. Finally, it is also possible that urban, socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods may have low levels of social cohesion (Feldman & Steptoe, 2004); if individuals do not feel connected to their neighbors, perceptions of their neighbors’ behavior may not influence their own behavior.

Syndemics theory suggests that psychosocial conditions and diseases co-occur and interact with each other, resulting in magnified or worsened health consequences (Singer & Clair, 2003). HIV researchers have proposed that there is a syndemic, wherein substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS (SAVA) cluster and amplify each other to result in poor health outcomes; the SAVA syndemic framework has also been expanded to include mental health (Meyer, Springer, & Altice, 2011). Our work supports the notion of a SAVA syndemic; that is, substance abuse, violence, mental health, and sexual risk behavior were interrelated in this sample of urban STI clinic patients. In current conceptualizations of the SAVA syndemic, violence is frequently defined as child and adult physical or sexual assault, and/or intimate partner violence (Meyer et al., 2011). Our work suggests that the violence aspect of the SAVA syndemic should be expanded to include community violence exposure.

Strengths of our study include the large sample, which allowed us to test complex models and to test associations by sex. Most of our participants reported both high rates of community violence and sexual risk behavior; thus, this is an important population in which to better understand mediators of the community violence-sexual risk behavior relation, with the ultimate goal of intervening on these mediators to reduce sexual risk behavior. Finally, controlling for individual- and census tract-level SES, which are associated both with community violence and with sexual risk behavior, was a strength of our study.

Limitations of our study include not assessing PTSD, which may be an important mediator of the community violence-sexual behavior relation (Voisin et al., 2014). Second, we did not assess injunctive norms, which may be a more powerful predictor than descriptive norms. Third, our study was cross-sectional, limiting inferences about causality. It may be, for example, that having sex with non-steady partners leads to IPV or that high levels of substance use affect the choice of neighborhoods (e.g., individuals may choose to live in neighborhoods with high densities of liquor stores or bars, or where drugs are frequently sold, which may also be the most violent neighborhoods). Longitudinal research can help to clarify the direction of effects. Although it can be a challenge to retain people who frequently relocate in a longitudinal study, this transitory aspect may provide a unique opportunity to better understand the impact of community violence on health and health behaviors (Cooper et al., 2015). Fourth, several of the indirect effects we report were only marginally significant at the p < .10 level. We chose to report these marginally significant indirect effects because (1) power for testing indirect effects is low relative to power for testing main effects, and (2) these marginally significant effects are consistent with the theory we described in the Introduction. However, because these indirect effects were only marginally significant, they should be interpreted cautiously, and additional studies are needed to determine whether these indirect effects can be replicated. Finally, we used census tract as a proxy for neighborhood to create our census tract-level SES, aggregate partner norms, and aggregate condom use norms variable. However, as noted above, census tracts can be large and heterogeneous; in addition, census tracts may not accurately reflect participants’ perceptions of their neighborhoods.

Even though causality cannot be inferred from these data, it is likely that reducing community violence would reduce sexual risk behavior, improve mental health, and reduce substance use and IPV. Despite these benefits, it is difficult to imagine how such an intervention could feasibly be conducted. Therefore, to improve sexual health among individuals living in neighborhoods characterized by community violence, it may be more practical to implement interventions to improve mental health, and to reduce substance use and intimate partner violence, which mediate the community violence-sexual risk behavior relation.

In conclusion, we found that community violence is associated with sexual risk behavior for both men and women, and that mental health, substance use, and IPV mediated this relation. Associations and mediators differed by sex and by sexual behavior outcome. Future research in this area should consider potential sex differences, and should investigate multiple sexual behavior outcomes. Longitudinal research is needed to clarify the direction of effects.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH068171) to Michael P. Carey.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

These data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Fishbein M, Muellerleile PA. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:142–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer K, Wallis AB, Hamberger LK. Neighborhood environment and intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence and Abuse. 2015;16:16–47. doi: 10.1177/1524838013515758. doi:10.1177/1524838013515758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS. Lifetime community violence exposure and health risk behavior among young adults in college. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:610–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.007. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmbhatt H, Kagesten A, Emerson M, Decker MR, Olumide AO, Ojengbede O, Delany-Moretlwe S. Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in urban disadvantaged settings across five cities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:S48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.023. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Burrington LA. Racial differences in sexual and fertility attitudes in an urban setting. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:236–251. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthén B. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;105:456–466. [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Kalichman SC. Risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among persons with severe mental illnesses. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17:271–291. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Senn TE, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA, Vanable PA, Carey KB. Optimizing the scientific yield from a randomized controlled trial (RCT): Evaluating two behavioral interventions and assessment reactivity with a single trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;36:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.06.019. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Senn TE, Walsh JL, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA, Fortune T, Carey KB. Evaluating a brief, video-based sexual risk reduction intervention and assessment reactivity with STI clinic patients: Results from a randomized controlled trial. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19:1228–1246. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0960-3. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0960-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DL, McNulty TL, Bellair PE, Watts S. Neighborhoods and racial/ethnic disparities in adolescent sexual risk behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:1536–1549. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0052-0. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-0052-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007-2010. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data-United States and 6 dependent areas-2011. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2014. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Clark C, Ryan L, Kawachi I, Canner MJ, Berkman L, Wright RJ. Witnessing community violence in residential neighborhoods: A mental health hazard for urban women. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85:22–38. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9229-8. doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9229-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. “Broken windows” and the risk of gonorrhea. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:230–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Explore Study Team Substance use and sexual risk: A participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32:156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HL, Linton S, Haley DF, Kelley ME, Dauria EF, Karnes CC, Bonney LE. Changes in exposure to neighborhood characteristics are associated with sexual network characteristics in a cohort of adults relocating from public housing. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19:1016–1030. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0883-z. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0883-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cubbin C, Santelli J, Brindis CD, Braveman P. Neighborhood context and sexual behaviors among adolescents: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2005;37:125–134. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.125.05. doi:10.1363/psrh.37.125.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry A, Latkin C, Davey-Rothwell M. Pathways to depression: The impact of neighborhood violent crime on inner-city residents in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.007. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:844–854. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164374.32229.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, Sionean C, Brown LK, Rothbaum B, Davies S. A prospective study of psychological distress and sexual risk behavior among black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E85. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, Hemphill SA. Social norms in the development of adolescent substance use: A longitudinal analysis of the International Youth Development Study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:1486–1497. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0111-1. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0111-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Suchday S. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: Development and validation of a Neighborhood Stress Index. Health Psychology. 2002;21:254–262. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, Abbott JT. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:1357–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman PJ, Steptoe A. How neighborhoods and physical functioning are related: The roles of neighborhood socioeconomic status, perceived neighborhood strain, and individual health risk factors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:91–99. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_3. doi:10.1207/s15324796abm2702_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual-level change in HIV risk behavior. In: Peterson JL, DiClemente RJ, editors. Handbook of HIV prevention. Kluwer Academic; New York: 2000. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JL, Browning CR. Effects of exposure to violence with a weapon during adolescence on adult hypertension. Annals of Epidemiology. 2014;24:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Olchowski A, Gilreath T. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. doi:10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, HIV Incidence Surveillance Group Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. doi:10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess KL, Javanbakht M, Brown JM, Weiss RE, Hsu P, Gorbach PM. Intimate partner violence and sexually transmitted infections among young adult women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2012;39:366–371. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182478fa5. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182478fa5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: A retrospective cohort study. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton HE, Lyketsos CG, Zenilman JM, Thompson RE, Erbelding EJ. Depression and HIV risk behaviors among patients in a sexually transmitted disease clinic. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:912–914. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton HE, Treisman GJ, Hunt WR, Fishman M, Kendig N, Swetz A, Lyketsos CG. HIV risk behaviors and their relationship to posttraumatic stress disorder among women prisoners. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:508–513. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Redding CA, DiClemente RJ, Mustanski BS, Dodge B, Sheeran P, Fishbein M. A network-individual-resource model for HIV prevention. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:204–221. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9803-z. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9803-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JC, Valois RF, Siddiqi A, Vanable P, Carey MP. Neighborhood condition and geographic locale in assessing HIV/STI risk among African American adolescents. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19:1005–1013. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0868-y. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0868-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MR, Kaufman JS, Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Adimora AA, Weir SS, Miller WC. Depression, sexually transmitted infection, and sexual risk behavior among young adults in the United States. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:644–652. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.95. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Zaharakis N. Community violence exposure, coping, and problematic alcohol and drug use among urban, female caregivers: A prospective study. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;55:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.020. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S. Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics. 2006;118:189–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1320. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Lee CM, Patrick ME, Fossos N. Gender-specific normative misperceptions of risky sexual behavior and alcohol-related risky sexual behavior. Sex Roles. 2007;57:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: A literature review of the syndemic. J Womens Health. 2011;20:991–1006. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2328. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M, Senn TE, Carey MP. Mediators of the relation between partner violence and sexual risk behavior among women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38:510–515. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318207f59b. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318207f59b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology. 2001;39:517–559. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Windle M. Initiation of alcohol use in early adolescence: Links with exposure to community violence across time. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:779–781. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, Seltzer JA, Schwartz CR. Neighborhood norms and substance use among teens. Social Science Research. 2008;37:138–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 7th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2013. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Edusei K, Jr., Chesson HW, Gift TL, Tao G, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, Kent CK. The estimated direct medical cost of selected sexually transmitted infections in the United States, 2008. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2013;40:197–201. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318285c6d2. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318285c6d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DY, Walsh B, Bullion JW, Reid PV, Bacon K, Okoro N. The intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV in U.S. women: A review. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2014;25:S36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.12.006. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan C, Mennerich A, Sexton E, James SE. Community violence and its direct, indirect, and mediating effects on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1132–1149. doi: 10.1177/1077801206294115. doi:10.1177/1077801206294115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin BA, Green KM, Milam AJ, Furr-Holden CD, Ialongo NS. Neighborhood environment and urban African American marijuana use during high school. Journal of Urban Health. 2014;91:1189–1201. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9909-0. doi:10.1007/s11524-014-9909-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed E, Silverman JG, Welles SL, Santana MC, Missmer SA, Raj A. Associations between perceptions and involvement in neighborhood violence and intimate partner violence perpetration among urban, African American men. Journal of Community Health. 2009;34:328–335. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9161-9. doi:10.1007/s10900-009-9161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: An update of research findings. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivis A, Sheeran P. Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Current Psychology. 2003;22:218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Fikretoglu D, Bowser F, Hurley JD, Pappert CA, Romero N, van Voorhees E. Community violence exposure in university students: A replication and extension. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: A primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1999;8:3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. doi:10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA. Childhood sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior among men and women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:720–731. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.720. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, DiClemente RJ, Lovvorn AE. State of the evidence: Intimate partner violence and HIV/STI risk among adolescents. Current HIV Research. 2013;11:528–535. doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140129103122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Raiford JL, Robinson LS, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Intimate partner violence and other partner-related factors: Correlates of sexually transmissible infections and risky sexual behaviours among young adult African American women. Sexual Health. 2010;7:25–30. doi: 10.1071/SH08075. doi:10.1071/SH08075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in the bio-social context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2003;17:423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Fitzamurice GM, Williams DR, Gilman SE. Common patterns of violence experiences and depression and anxiety among adolescents. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012;47:1591–1605. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0466-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S, Treger S, Sakaluk JK. Premarital sexual standards and sociosexuality: Gender, ethnicity, and cohort differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:1395–1405. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Ramirez IL. Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:281–290. doi: 10.1002/ab.20199. doi:10.1002/ab.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A, O'Donnell L. Urban young women's experiences of discrimination and community violence and intimate partner violence. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85:386–401. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9265-z. doi:10.1007/s11524-008-9265-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Alemdar M, Whitaker DJ. Nonreciprocal and reciprocal dating violence and injury occurrence among urban youth. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;11:264–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR. The relationship between violence exposure and HIV sexual risk behavior: Does gender matter? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:497–506. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.497. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, Hotton AL, Neilands TB. Testing pathways linking exposure to community violence and sexual behaviors among African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:1513–1526. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0068-5. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-0068-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JL, Senn TE, Carey MP. Exposure to different types of violence and subsequent sexual risk behavior among female STD clinic patients: A latent class analysis. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:339–354. doi: 10.1037/a0027716. doi:10.1037/a0027716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner TD, Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA. Everybody's doin' it (Right?): Neighborhood norms and sexual activity in adolescence. Social Science Research. 2011;40:1676–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.06.009. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LS. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:941–947. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Shiffman S. Coping and substance use: A conceptual framework. In: Shiffman S, Wills TA, editors. Coping and substance abuse. Academic Press; New York: 1985. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. Sexually transmitted diseases among adults who had been abused and neglected as children: A 30-year prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:S197–203. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131599. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.131599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Woods BA, Emerson E, Donenberg GR. Patterns of violence exposure and sexual risk in low-income, urban African American girls. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:194–207. doi: 10.1037/a0027265. doi:10.1037/a0027265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JQ, Kelling GL. The police and neighborhood safety: Broken windows. Atlantic Monthly. 1982;127:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WC, Rosenthal BS. The relationship between exposure to community violence and psychological distress among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:335–352. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright EM, Fagan AA, Pinchevsky GM. The effects of exposure to violence and victimization across life domains on adolescent substance use. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013;37:899–909. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.010. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Hanson RF, Smith DW, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Witnessed community and parental violence in relation to substance use and delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22:525–533. doi: 10.1002/jts.20469. doi:10.1002/jts.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick H, Hanson R, Smith D, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Prevalence and mental health correlates of witnessed parental and community violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:441–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02004.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]