Abstract

In November 2012, a dairy farmer in the district Kleve first observed a reduction in milk yield, respiratory symptoms, nasal discharge, fever, sporadic diarrhoea and sudden deaths in dairy cows and calves. In the following months, further farms were found infected with cattle showing similar clinical signs. An epidemiological investigation was carried out to identify the source of infection, the date of introduction, potential transmission pathways and to analyse the extent of the epidemic. Furthermore, laboratory analyses were conducted to characterise the causative agent. BVDV had been diagnosed in the index herd in December 2012, but due to the atypical clinical picture, the virus was not immediately recognised as the causative agent. Further laboratory analysis showed that this outbreak and subsequent infections in the area were caused by a BVD type 2c virus with a characteristic genome insertion, which seems to be associated with the occurrence of severe clinical symptoms in infected cattle.

Epidemiological investigations showed that the probable date of introduction was in mid-October 2012. The high risk period was estimated as three months. A total of 21 affected farms with 5325 cattle were identified in two German Federal States. The virus was mainly transmitted by person contacts, but also by cattle trade and vehicles. The case-fatality rate was up to 60% and mortality in outbreak farms varied between 2.3 and 29.5%.

The competent veterinary authorities imposed trade restrictions on affected farms. All persons who had been in contact with affected animals were advised to increase biosecurity measures (e.g. using farm-owned or disposable protective clothing). In some farms, affected animals were vaccinated against BVD to reduce clinical signs as an “emergency measure”. These measures stopped the further spread of the disease.

Keywords: Bovine viral diarrhea, Pestivirus, BVDV-2, Outbreak, Germany, Epidemiology

1. Introduction

Bovine viral Diarrhea (BVD), caused by the Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) leads to severe disease and significant economic losses and is therefore regarded as one of the most important infectious diseases in cattle (Fourichon et al., 2005, Gunn et al., 2005, Houe, 2003, Stähl and Alenius, 2012). BVDV comprises of a heterogeneous group of viruses, which primarily infect ruminants and vary in antigenicity, cytopathogenicity and virulence. They belong to the genus Pestivirus of the Flaviviridae family. The BVDV genome consists of a single-stranded RNA of positive orientation and is prone to a high mutation rate, which leads to genetic heterogeneity. This heterogeneity helps BVDV and other pestiviruses to adapt and evade host immune systems (Ridpath, 2003) Currently, BVDV is subdivided into two species, BVDV-1 and -2 (King et al., 2011, Becher and HJT, 2011). Both genotypes occur in two different biotypes, i.e. cytopathogenic (cp) and non-cytopathogenic (ncp) viruses (Peterhans et al., 2010). Cattle and sheep can be infected by both BVDV genotypes resulting in reproductive, enteric and respiratory disorders. Clinical presentations range from mild subclinical infections in immunocompetent cattle to highly fatal disorders (Lanyon et al., 2014, Yilmaz et al., 2012). In particular, virulent BVDV-2 strains are associated with severe clinical disease such as the hemorrhagic syndrome (Corapi et al., 1989, Liebler et al., 1995, Rebhun et al., 1989, Scruggs et al., 1995, Thiel, 1993) and mucosal disease like lesions (Hessman et al., 2012, Stoffregen et al., 2000) as a result of an acute infection. In addition, ncp viruses of both genotypes may cause persistent infection in cattle, which is the major source of viral spread in the cattle population. Furthermore, mutation and recombination events leading to a change of the biotype from ncp to cpor super infections with a homologous cpisolate can result in fatal mucosal disease (Brownlie, 1990a, Brownlie, 1990b, Ridpath and Bolin, 1995a, Ridpath and Bolin, 1995b).

Due the economic impact of BVD, eradication programs without the use of vaccines were started in 1993 and 1994 in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden (Moennig et al., 2005). In 2004, a nationwide eradication program was launched in Austria (Obritzhauser et al., 2005) and in 2008, Switzerland started a BVD eradication program by testing in a first stage all animals for persistent BVDV infections and subsequently all calves by using tissue samples collected during ear-tagging (Presi and Heim, 2010, Presi et al., 2011).

In Germany, BVD was declared a notifiable disease in 2004. Most of the federal states started optional or compulsory eradication programs which may differ between the federal states. Later it was decided to implement a compulsory, nationwide eradication programing Germany (Verordnung zum Schutz der Rinder vor einer Infektion mit dem Bovinen Virusdiarrhoe-Virus (BVDV-Verordnung) vom 11. Dezember 2008) focusing on the detection of persistently infected (PI) animals e.g. using ear-notch samples and subsequent slaughter of those virus carriers. All test results are recorded in detail in the national cattle registration database in the “Herkunftssicherungs- und Informationssystem für Tiere” (HI-Tier). According to this database, from January 2011 until September 2013, more than 40,000 PI animals were detected and removed.

Parallel to PI detection, vaccination against BVDV is allowed. However, the acceptance of BVDV vaccines and the willingness of cattle farmers to have their herds vaccinated is low (e.g. due to the cases of bovine neonatal pancytopenia, which were associated with the use of one particular BVDV vaccine (Bastian et al., 2011, Deutskens et al., 2011)). Hence, more and more cattle and cattle herds become naïve to BVDV.

In Germany, the predominant BVDV genotype is BVDV-1 (Beer et al., 1997, Liebler-Tenorio et al., 2006, Tajima et al., 2001, Wolfmeyer et al., 1997). The analysis of about 600 BVDV isolates between 2008 and 2014 revealed that the BVDV subtypes 1b and 1d were most prominent (about 70% of all isolates tested). Strains of subtypes BVDV-1f (10.5%), BVDV-1e (4.1%), BVDV-1h (2.9%), BVDV-1g (0.5%) and BVDV-1k (0.5%) were found to a lower extent. The percentage of BVDV-2 was 9.5% (Schirrmeier, 2014). In contrast, surveys in the USA revealed considerably higher BVDV-2 prevalence of up to 39%, calculated on the basis of the submission of isolates to diagnostic laboratories (Liebler-Tenorio et al., 2006).

In the beginning of November 2012, a dairy farmer in the district Kleve observed a reduction in milk yield, respiratory symptoms, nasal discharge, fever, sporadic diarrhoea and sudden deaths in dairy cows and calves. BVDV BVDV-2 was first diagnosed in Mid-February 2013. The causative agent was typed as BVDV-2c with a characteristic genomic insertion (Jenckel et al., 2014). Thereafter, several farms (dairy and beef) in districts located in at least two German federal states reported similar symptoms in cattle with severe illness and a frequently lethal outcome. To establish the date of introduction, the high risk period (HRP), i.e. the time period between the introduction of the agent and the identification of the agent, transmission pathways between farms and the main routes of transmission, the epidemiological task force of the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut (FLI) investigated the course of the epidemic together with the local veterinary authorities.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Epidemiological investigations

During the on-site investigations of the epidemiological task force of the FLI, eight farms were visited in cooperation with the local veterinary authorities between 20 and 22 March 2013. These farms were located in the districts of Kleve (1), Viersen (1), Borken (3), Emsland (2) and Ammerland (1). Six of them were mixed (dairy and beef), two beef farms. The mixed farms held cows for milk production, female offspring was used for restocking, and male calves were fattened. Some farmers bought additional calves for fattening. One farm sold the male off spring and bought calves of beef breeds instead for fattening. The two fattening farms operated exclusively as calf-rearing enterprises (Table 1, visited farms are marked).

Table 1.

List of affected farms (in bold: farms visited by FLI).

| Outbreak number | Type of farm | Suspected time of introduction | Livestock during period of introduction (n) |

Losses (n) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Calves | Young cattle | Cows | Total | (%) | Calves | (%) | Young cattle | (%) | Cows | (%) | |||

| O1 (index) | Mixed | Mid-October 2012 | 174 | 20 | 49 | 105 | 19 | (10.9) | 11 | (55.0) | 5 | (10.2) | 3 | (2.9) |

| O2 | Mixed | Early January 2013 | 78 | 15 | 20 | 43 | 23 | (29.5) | 11 | (73.3) | 2 | (10.0) | 10 | (23.3) |

| O3 | Mixed | Mid-January 2013 | 444 | 87 | 172 | 185 | 36 | (8.1) | 21 | (24.1) | 8 | (4.7) | 7 | (3.8) |

| O4 | Mixed | Late January 2013 | 110 | 16 | 41 | 53 | 8 | (7.3) | 4 | (25.0) | 1 | (2.4) | 3 | (5.7) |

| O5 | Mixed | Late January 2013 | 74 | 13 | 19 | 42 | 5 | (6.8) | 5 | (38.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| O6 | Mixed | Late January 2013 | 323 | 38 | 169 | 116 | 26 | (8.0) | 20 | (52.6) | 6 | (3.6) | 0 | (0.0) |

| O7 | Mixed | Early February 2013 | 242 | 63 | 76 | 103 | 29 | (12.0) | 21 | (33.3) | 5 | (6.6) | 3 | (2.9) |

| O8 | Mixed | Early February 2013 | 171 | 92 | 43 | 36 | 34 | (19.9) | 33 | (35.9) | 1 | (2.3) | 0 | (0.0) |

| O9 | Beef | Early February 2013 | 228 | 226 | 2 | 0 | 71 | (31.1) | 71 | (31.4) | 0 | (0.0) | ||

| O10 | Beef | Early February 2013 | 769 | 768 | 1 | 0 | 132 | (17.2) | 132 | (17.2) | 0 | (0.0) | ||

| O11 | Mixed | Early February 2013 | 294 | 52 | 179 | 63 | 29 | (9.9) | 22 | (42.3) | 7 | (3.9) | 0 | (0.0) |

| O12 | Mixed | Early February 2013 | 91 | 28 | 61 | 2 | 5 | (5.5) | 5 | (17.9) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| O13 | Mixed | Early March 2013 | 171 | 46 | 104 | 21 | 9 | (5.3) | 7 | (15.2) | 2 | (1.9) | 0 | (0.0) |

| O14 | Mixed | Early March 2013 | 119 | 16 | 64 | 39 | 9 | (7.6) | 4 | (25.0) | 2 | (3.1) | 3 | (7.7) |

| O15 | Beef | Early March 2013 | 343 | 97 | 246 | 0 | 8 | (2.3) | 6 | (6.2) | 2 | (0.8) | ||

| O16 | Mixed | Late March 2013 | 127 | 12 | 36 | 79 | 13 | (10.2) | 3 | (25.0) | 3 | (8.3) | 7 | (8.9) |

| O17 | Beef | Late March 2013 | 220 | 130 | 88 | 2 | 36 | (16.4) | 35 | (26.9) | 1 | (1.1) | 0 | (0.0) |

| O18 | Mixed | Early April 2013 | 616 | 57 | 375 | 184 | 15 | (2.4) | 10 | (17.5) | 4 | (1.1) | 1 | (0.5) |

| O19 | Mixed | Early April 2013 | 208 | 21 | 53 | 134 | 14 | (6.7) | 1 | (4.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 13 | (9.7) |

| O20 | Mixed | Early April 2013 | 283 | 40 | 72 | 171 | 18 | (6.4) | 8 | (20.0) | 4 | (5.6) | 6 | (3.5) |

| O21 | Mixed | Mid-April 2013 | 240 | 53 | 105 | 82 | 38 | (15.8) | 19 | (35.8) | 3 | (2.9) | 16 | (19.5) |

Before each on-site visit, the epidemiological task force of the FLI was informed by the local veterinary authority about the respective case history. This included previous investigations, particularly the results of clinical inspections performed by the local veterinary authority and veterinary practitioners, and any measures taken to avoid the further spread of the disease. The visits consisted of an inspection of the whole farm including animal housing, milk room, technical and outside facilities (storage of fodder, dung, etc.) and clinical inspections of the animals. Operating procedures and the locations, where symptoms were first observed, the structure and condition of the farm in general were analyzed. After the inspection, a structured interview followed which primarily focused on contacts. Information on direct (animal trade, personal contacts) and indirect transmission (vehicle-born) was retrieved and analyzed.

Farm-specific information on the number of cattle kept, the numbers of calves, heifers and cows, proportion of beef and dairy cattle, trade and animal losses was obtained from the HI-Tier database. Data on individual animals such as the date of birth, locations, where the animals had been kept during their life, vaccinations and test results for BVD were also obtained from the HI-Tier database. Another 13 farms were analyzed by using only data provided by the local authorities, the involved diagnostic laboratories and HI-Tier data (Table 1).

2.2. Laboratory investigations

Animals were tested for BVDV by the veterinary investigation centers of the respective federal states (Chemisches und Veterinäruntersuchungsamt Rhein-Ruhr-Wupper (CVUA-RRW) for North Rhine-Westphalia and the Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit (LAVES) for Lower Saxony) and the National Reference Laboratory (NRL) for BVDat the FLI. Antigen detection was performed using a commercial ERNS-ELISA (IDEXX Laboratories). Virus isolation and phenotyping with monoclonal antibodies was done according to the German “Official Collection of Methods for the Sampling and Investigation of Materials of Animal Origin for Notifiable Animal Diseases” (http://www.fli.bund.de/de/startseite/publikationen/amtliche-methodensammlung.html). Positive ELISA results were confirmed by real-time RT-PCR using a commercial kit (Virotype BVDV, Qiagen Leipzig) according to Hoffmann et al. (Hoffmann et al., 2006). Furthermore, real-time RT-PCRs for the rapid identification of the characteristic genome insertion were established and used for a fast typing.

2.3. Virus characterization

A first virus characterization and molecular analysis was done by conventional RT-PCR and 5′NTR sequencing as described by Schaarschmidt et al. (2000), and thereafter for a few virus isolates by next-generation sequencing (Jenckel et al., 2014). To ensure a rapid and specific detection of the BVDV 2c subtype, a subtype-specific real-time RT PCR was developed and also established in the regional laboratories. Briefly, available nucleotide sequences of the 5′NTR of BVDV-2c strains were aligned and compared with consensus sequences of BVDV-1, -2a and -2b strains published in GenBank. Specific nucleotides only available in BVDV-2c strains were used for the development of a BVDV-2c specific real-time RT-PCR assay. The forward primer BVDV2c-134-F (5′-TGG ACG AGG GCA TGC CCA A-3′) and the reverse primer BVDV2c-207-R (5′-ACA CCG TGA GTG GTG CTT TTG-3′) were combined with the TaqMan probe BVDV2c-182FAM_as (5′-FAM-ATG CAA CCC CCG CAT AGG TTA AGA TGT G -BHQ1-3′). For amplification, the AgPath-ID™ One-Step RT-PCR Reagents kit (Life Technologies) was used. The assays were optimized using a total reaction volume of 25 μl. For one reaction, 4.5 μl RNase-free water, 12.5 μl 2× RT-PCR buffer, 1.0 μl enzyme mix, 2.0 μl of a primer-probe-mix (7.5 pmol/μl primer and 2.5 pmol/μl probe) and 5 μl RNA template were mixed. The following thermal program was applied: 1 cycle of 45 °C for 10 min and 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 30 s.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology

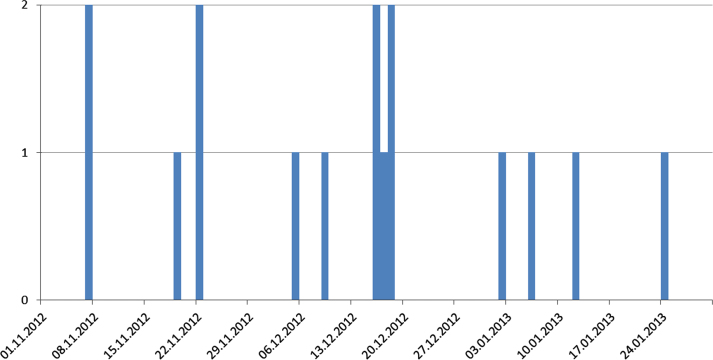

The analysis of the interviews, the data provided by the official veterinarians and the HI-Tier data indicated that a dairy farm with about 174 cattle in the district of Kleve (located in North Rhine-Westphalia) was the most likely index case (outbreak 1, O1): In early November 2012, the farmer observed a slight reduction in milk yield of about 2.5 l compared to the previous year and a calf with respiratory symptoms on 7 November 2012, which died on the following day. It was necropsied and diagnosed with pneumonia at the state veterinary institute (CVUA-RRW) of North Rhine-Westphalia; the animal was not tested for BVD. In Mid-November, the farmer observed respiratory symptoms, nasal discharge, fever, sporadic diarrhoea, sudden deaths (one cow, later on one calf) and abortions. Although initially only a few animals were affected, the disease appeared to spread within the herd. Shortly after, more calves were affected, which showed respiratory symptoms and fever. Eight calves, five heifers and three cows died between November 2012 and the end of January 2013 (Fig. 1). Another three calves died in March 2013 (Table 1). BVDV was first diagnosed by cell culture in two foetuses aborted on 7 December 2012 and one calf that died on 11 December 2012, but no further virus typing was done at this time. In mid-December, five heifers from another stable of the same farm were integrated in the dairy herd. Two of them developed severe symptoms with fever, respiratory symptoms and diarrhoea, and died within a few days. Samples from an animal that had died on 12 January 2013 were tested for BVDV at CVUA-RRW and FLI. The virus isolate was typed as BVDV type 2c.

Fig. 1.

Numbers of animals that died in the index farm between November 2012 and January 2013.

Assuming that the calf that had died on 8 November 2012 was the first infected animal and assuming an incubation period of 2 to 14 days, the most probable date of introduction of the virus into the herd was between the end of October and the 5 November 2012. If this calf was not the first infected animal, the date of introduction might have been earlier. Hence, the high risk period (time between introduction and confirmation) was about 45 days for BVD and 106 days for BVDV-2c.

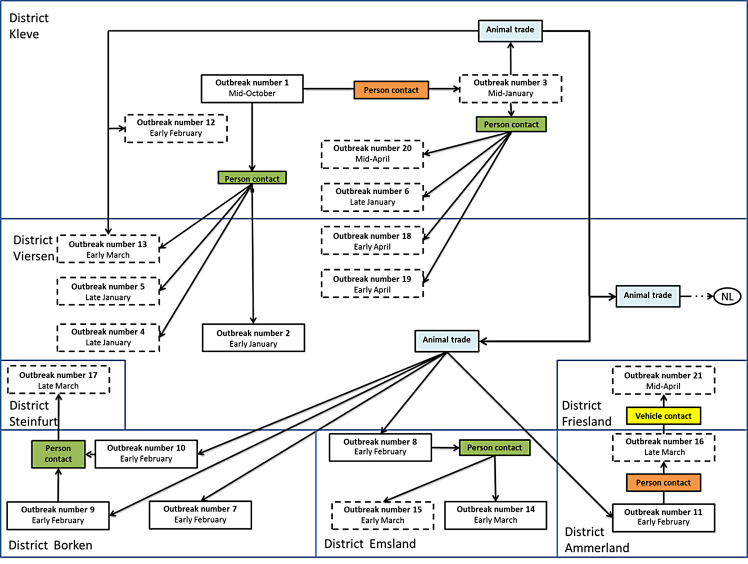

From the initial outbreak, the virus spread to at least 20 farms in North-Rhine Westphalia (n = 14) and Lower Saxony (n = 6) and to a few farms in the Netherlands (n = 4). In detail, BVDV-2c was transmitted to four farms within the same (Kleve) and one bordering district (Viersen, North Rhine-Westphalia) (Fig. 2). One of these outbreaks (outbreak No. 2, O2) was most likely caused by person contact, and for three outbreaks (O3, O4, and O), the most probable route of transmission was also person contact, in this case a veterinary practitioner.

Fig. 2.

Connections and putative transmission pathways between affected farms. Farms with solid lines have been visited by FLI, for farms with dashed lines, data provided by the local authorities. The transmission by person contacts is divided in farm veterinarians (green) and other person contacts (orange).

The second outbreak (O2) was noticed in a mixed farm (dairy/beef) in the district of Viersen (North Rhine-Westphalia), where sudden deaths had occurred in calves between 1 and 4 January 2013. With a delay of one week, symptoms ranging from reduction in milk yield to diarrhoea and fever occurred in several cows of the same farm. Between 1 January and 18 February 2013, a total of 23 animals died or were culled (Table 1). No animal contacts between this farm and the index case were recorded, but the farmers were friends and met during the outbreak. Hence, the most likely route of introduction of BVDV-2c was person contact.

On 13 January 2013, sudden deaths in calves occurred in a dairy farm in the district of Kleve (O3). Until 22 February 2013, a total of 36 animals died or had to be culled. From O3 the infection spread to at least 10 other farms in North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony; to six of them by animal trade and to four by person contact. Furthermore, the virus was transmitted to farms in the Netherlands by animal trade. On 28 January 2013, farm 3 (O3) sold a calf to a cattle-dealer, who sold it to a colleague. During these transactions, the calf had contact to several other calves. These contacts probably led to another six outbreaks (Fig. 2). In farms O7, O8 and O11, the bought calves showed clinical signs one to five days after they were housed (1–4 February 2013) and some died. In farms O9 and O10, symptoms arose in some of the housed calves between 5 and 15 February 2013.

For twelve outbreaks, the most probable source of infection was the farm veterinarian (Fig. 2). For one transmission (O16 to O21), the only contact between both farms was a slurry vehicle that had been used as shared equipment. In summary, most of the secondary outbreaks were probably caused by person contacts (n = 13, 65%), often by veterinarians (n = 12, 60%), followed by trade contacts (n = 6, 30%) and vehicle contacts (n = 1, 5%).

3.2. Clinical signs

In the first stage of the infection, affected animals showed signs similar to pneumonia: increased breath rate, nasal and eye discharge, exhaustion, and fever up to 41 °C. The fever did not disappear when the animals received antibiotic medication. The animals developed diarrhoea (bloody or watery or sero-mucous) within hours to days, in severe cases they showed also signs of exsiccosis. Petechial bleedings were found on the mucosae of the conjunctiva and the mouth. The haemogram of diseased cattle was characterized by leuco- and thrombocytopenia. The health status of infected cattle deteriorated rapidly, and in severe cases, the first animals died two to three days after the onset of clinical signs. Some animals showed also erosions and ulcerations of the mucosa of the digestive system. In cows, additional symptoms included reduction in milk yield, abortion, reduction in fertility and chronic weight loss. Some affected calves lost weight and had a stunted growth.

Symptoms had generally started with respiratory signs, later followed by diarrhoea. The variation in symptoms was high, sometimes only one age group was affected and there were also animals that failed to show any clinical signs. In some farms, where persistently BVDV-infected animals had been found within the last two years or where the last BVDV vaccination campaign had been completed within the last two years, only younger animals were affected.

The mortality in the affected farms and between age groups differed largely. The overall mortality varied between 2.3% (O15) and 31.1% (O9). In general, calves were much more heavily affected than adult cattle and showed a mortality (number dead animals divided by the total number of cattle in the farm) of up to 73% (O2, Table 1). Losses of up to 50% in calves younger than three months were observed in O1, O3, O6 and O10 (Table 1). In outbreak 10, a beef farm consisting of three stables, 146 calves were housed in stable unit 1 by the end of January 2013. Until 9 April 2013, a total of 110 calves had died or had to be culled for animal welfare reasons (75.34%). However, the animals in the other two stables were not affected. With regard to cows, no animals died in 7 farms, mortality was below 10% in 16 farms and in two farms it was 19.5% or 23%, respectively (Table 1).

3.3. Diagnosis

On 7 December 2012, two aborted foetuses from O1 tested positive for BVDV. The genotype had not yet been determined at that time. Since clinical disease persisted, further samples from O1, O2, O3 and O4 were analysed in January 2013 and the agents genotyped (Table 1). The samples were submitted to the national reference laboratory for BVDV at the FLI, and the detected virus was characterised by 5′-NTR-sequencing as a genotype BVDV-2c. Subsequently, highly similar viruses were detected in all other herds of this study. The nucleotide identity in the 5′-NTR was 99% relative to isolates, which had been found in several cases in Germany in the years before; however, these isolates had not been associated with severe clinical symptoms (Schirrmeier, 2013). Deep sequencing revealed the coexistence of three distinct genome variants within recent highly virulent bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2 (BVDV-2) isolates. While most (ca. 95%) of the population harbored a duplication of a 222-nucleotide (nt) segment within the p7-NS2-encoding region, a minority displayed the standard structure of a BVDV-2 genome (for details see Jenckel et al., 2014). The viral genome loads measured in blood samples and organs of affected animals was regularly at a level that is normally only found in PI animals (e.g. ct-values in real-time RT-PCR < 25). By identifying and retesting suspect animals in the affected farms, we found that in individual surviving animals, an unusual long-lasting viremia and virus shedding, sometimes connected to persisting clinical signs for up to 8 weeks. Furthermore, in some affected farms housed animals got diseased indicating that the agent was still circulating.

3.4. Control strategy

3.3.1. Trade and hygiene

After BVDV-2c had been detected, movement restrictions were imposed on the affected farms, i.e. it was not allowed to move animals from the farm. Some farms tried to restock by purchasing cattle, but some of these (unvaccinated) animals contracted the infection and developed clinical disease.

It was discussed to disinfect the stables, slurry, etc., but since the animals were still kept in stables and because the buildings in several cases were deemed unsuitable for disinfection, it was decided that it was not possible to disinfect the premises. Nevertheless, the farmers and all other persons who had been in contact with the animals were advised to improve hygiene measures, e.g. to wear farm-owned clothing or one-way overalls when entering the premises. In some beef farms, culling of the affected herds, disinfection and restocking was considered, but not implemented as the current legislation did not allow the competent veterinary authorities to reinforce such measures.

3.3.2. Vaccination

Due to the high extent of animal losses, several affected herds were immunised with modified-live vaccine against BVDV (Vacoviron® FS, BVD/MD-virus, strain Oregon C24V) or a combination of inactivated vaccines and modified live vaccines without vaccinating clinically affected animals. In some farms, only female animals over 15 months of age were immunised, while all animals were vaccinated in others. Overall, immunisation was believed to have curbed the clinical signs, but no data are available to demonstrate the effect of vaccination. Furthermore, farmers in the whole affected region were advised to vaccinate their animals with modified-live vaccine against BVDV alone or in combination with an inactivated vaccine. In North-Rhine Westphalia about 1187 cattle farms were vaccinated.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spread

It took more than three months from the observation of the first clinical symptoms indicative of BVD until a highly virulent BVDV-2c was diagnosed as the causative agent. During this long period, the virus was able to spread. In previous studies, e.g. for classical swine fever, another pestivirus infection, similar delays were observed or simulated (Elber et al., 1999, Engel et al., 2005, Raulo and Lyytikäinen, 2007).

The delay in detecting and diagnosing highly virulent acute BVD can at least in part be explained by the fact that only a limited number of animals per herd were infected. Previous studies suggested that only 1–11% of the BVDV positive samples were BVDV-2 (Wolfmeyer et al., 1997) (11 out of 96), (Tajima et al., 2001) (5 out of 67). Furthermore, such severe symptoms in a high number of animals caused by BVDV in Germany are rare. The analysis showed that the disease was caused by a novel highly virulent BVDV-2c strain (hvBVDV-2c) that had not been observed in Germany before. It has been hypothesized that the major virus variant carrying the characteristic genome duplication of 222 nucleotides is responsible for the highly virulent phenotype (Jenckel et al., 2014). Hence, highly virulent BVDV was not in the focus of the attention of the cattle practitioners in that area in general, which may have contributed to delaying the diagnosis and to increasing the high risk period (HRP).

The BVDV control program in Germany concentrates on the detection and elimination of PI animals in the population as soon as possible similar as in the Swiss program (Presi et al., 2011). Transient infections are not in the main focus of the program as the clinical signs observed in adult animals are usually mild and only a few cases with massive clinical symptoms have been reported (Liebler et al., 1995, Martin et al., 2005). Nevertheless, farmers are advised to put purchased animals under quarantine first in order to minimize (1) the risk of transmission and (2) the risk of introducing PI animals by purchasing transiently infected animals. In view of the decreasing numbers of PI calves, many farmers ceased to have their cattle vaccinated. As a consequence, naïve subpopulations built up, which are highly susceptible to any BVDV infection. This might also have prompted the massive spread of BVDV-2 in Western Germany.

The investigations also showed that most of the secondary outbreaks were caused by person contacts (farmers or veterinarians, Fig. 2). Fritzemeier et al. (Fritzemeier et al., 2000) analyzed outbreaks of classical swine fever and also described that most secondary outbreaks were caused by trade, followed by ‘neighborhood’, person contacts and vehicles. Biosecurity was poor among farmers and veterinarians, who often used the same protective clothing on several farms, which may have contributed significantly to the spread of BVDV 2c. To avoid the dispersion of the virus, all participants should increase biosecurity measures.

As prolonged shedding of the virus in individual animals cannot be excluded, keeping these animals on affected farms might be a risk for susceptible animals that are introduced into the herd and also for other herds, if infected cattle are sold to other farms. In one farm (O11), BVDV-2c cases reoccurred after susceptible animals were introduced into this herd after some months. This can be also considered as a strong evidence for virus persistence in those farms by mechanisms other than persistently infected animals, e.g. due to the existence of chronic BVDV-2c carriers.

Hence, animals introduced into the herds should be protected by vaccination and kept in quarantine before they are included in the herd and animals that are sold should be tested before transport.

4.2. Clinical signs/diagnosis

Farmers from affected premises reported respiratory symptoms, diarrhoea, peracute death, nasal discharge, eye discharge, fever, lesions on the tongue and hypothermia in their cattle. This is in accord with reports on previous BVDV-2 outbreaks in Germany (Martin et al., 2005, Wolfmeyer et al., 1997), Canada (Carruthers and Petrie, 1996) and (David et al., 1994). The differences in mortality between farms can be explained by the fact that some of the farms had not had BVD infections in recent years while PI animals had been detected in others in 2012. Hence, some animals may have been at least partially protected by natural infection with BVDV 1.

However, a large number of animals showed severe clinical signs and the mortality as well as the case fatality rate was higher than in other BVDV outbreak scenarios in Europe. Nevertheless, the scenario is comparable other outbreak caused by highly virulent BVDV type 2 in Canada (Carman et al., 1998, Pellerin et al., 1994, Ridpath et al., 2006) and the USA (Ridpath et al., 2000). Similar to the description of Carman et al. (1998), some of the affected farms had purchased animals, which presumably introduced the virus into the farm. The mortality in the affected farms ranged between 2.3 and 31.1% (Table 1), comparable to the description of Carman et al. (1998). In contrast to the epidemicin Ontario, where about 850 farms were affected, the outbreaks in Germany were limited to 21 farms.

One of the reasons for the late detection of BVDV-2 may be that BVDV-2 infections are rare in Germany (Wolfmeyer et al., 1997) in combination with the fact that most cattle in the affected farms had been confirmed before as being not persistently infected with BVDV by ear-notch testing. The animals were therefore regarded as “BVDV unsuspicious”. Furthermore, at the beginning, pneumonia dominated a clinical sign that had previously not been regarded as a lead symptom for BVDV infection.

4.3. Control strategy/vaccination

As there was an emerging hvBVDV-2c situation, and due to the fact, that acute BVDV outbreak scenarios are not explicitly included in the German BVDV control program, the competent veterinary authorities imposed trade restrictions on the affected farms. Furthermore, all persons (e.g. veterinarians, farmers), who had been in contact with affected animals, were informed and advised to increase biosecurity measures (e.g. using farm-owned or disposable protective clothing). In some farms, affected animals were vaccinated to reduce clinical signs as an “emergency measure”.

All these control measures may have stopped the further spread of the disease as no more clinically affected farms were reported after 06 June 2013. The effect of vaccination is no clear as data sufficiently demonstrating the protective effect of emergency vaccination against hvBVDV-2c are not available. On the other hand, vaccination may not have led to protection from virus shedding. Furthermore, prolonged shedding by vaccinated animals cannot be excluded, and the spread of the disease could no longer be traced as many farmers started to immunise their animals against BVD with BVDV vaccines, which does not allow differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals.

The results of the epidemiological investigations also suggested that one farm had been infected by a contaminated vehicle (slurry tank). It was therefore decided to include the disinfection of slurry in the control measures. A study has showed that BVDV can survive for days to weeks in slurry depending on the temperature (Botner and Belsham, 2012). If there is enough capacity to store slurry, prolonged storage might therefore help to reduce the risk of transmission.

5. Conclusion

A novel highly virulent BVDV-2c (hvBVDV-2c) strain hit naïve cattle in Western Germany during the course of a BVDV-control program that focuses on diseases control by detection and slaughter of PI animals only. Approximately fifteen weeks elapsed between the observation of the first clinical signs in November 2012 and the conclusion that a novel hvBVDV-2c has emerged. Interestingly, the virus behaved very similar to highly virulent CSFV e.g. concerning severity of clinical signs, viral genome loads in diseased animals, spread and the overall morbidity and mortality rate (Moennig, 2000). To reduce the time between the onset of clinical signs and the diagnosis, veterinarians and laboratories need to be sensitised to include highly virulent BVDV as a differential diagnosis and to test the animals accordingly. As seen before in the US (Ridpath et al., 2006), such strains can emerge and spread rapidly, and will be of concern especially in naïve populations which are the consequence of most of our BVDV eradication programs in Europe. However, if the awareness is high and samples are taken early for diagnostics, modern detection and typing tools are available to help to reduce the HRP, so that effective measures such as movement restrictions, culling or immunisation of infected animals can be taken to limit the spread of the infection.

Hygiene standardsin cattle farms need to be improved at all levels in the cattle industry to minimize the spread of highly contagious diseases. All visitors should wear farm-ownedor disposable protective clothing to prevent the spread of infections via contact and fomites.

With regard to the German BVD control program, the outbreak of hvBVDV-2c showed that the objectives of the control program need be clearly defined and communicated. In the present situation, the program should also aim at protecting the cattle population by vaccination. Creating BVD-free herds or even a complete BVDV-antibody free population is extremely risky as naïve animals are fully susceptible to this highly contagious infection and severe losses may be the result of epidemics with virulent strains such as hvBVDV-2c. Furthermore, other BVDV-related atypical pestiviruses like the HoBi-strains are a risk as it is seen in Italy in recent years (Bauermann et al., 2013, Decaro et al., 2012a, Decaro et al., 2012b).

On the other hand, the outbreak showed that the existing control measures, like trade restrictions, increased biosecurity were suitable to stop the spread of the outbreak.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Jörn Gethmann, Timo Homeier, Mark Holsteg: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Horst Schirrmeier, Michael Saßerath, Bernd Hoffmann, Martin Beer, Franz J. Conraths: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

The authors received no funding from an external source.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the affected farmers and the local veterinary authorities for their cooperation.

References

- Bastian M., Holsteg M., Hanke-Robinson H., Duchow K., Cussler K. Bovine Neonatal Pancytopenia: Is this alloimmune syndrome caused by vaccine-induced alloreactive antibodies? Vaccine. 2011;29:5267–5275. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermann F.V., Ridpath J.F., Weiblen R., Flores E.F. HoBi-like viruses: an emerging group of pestiviruses. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2013;25:6–15. doi: 10.1177/1040638712473103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer M., Wolf G., Pichler J., Wolfmeyer A., Kaaden O.R. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in cattle infected with bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet. Microbiol. 1997;58:9–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botner A., Belsham G.J. Virus survival in slurry: analysis of the stability of foot-and-mouth disease, classical swine fever, bovine viral diarrhoea and swine influenza viruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;157:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie J. The pathogenesis of bovine virus diarrhoea virus infections. Rev. Sci. Tech. 1990;9:43–59. doi: 10.20506/rst.9.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie J. Pathogenesis of mucosal disease and molecular aspects of bovine virus diarrhoea virus. Vet. Microbiol. 1990;23:371–382. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90169-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman S., van Dreumel T., Ridpath J., Hazlett M., Alves D., Dubovi E., Tremblay R., Bolin S., Godkin A., Anderson N. Severe acute bovine viral diarrhea in Ontario, 1993-1995. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1998;10:27–35. doi: 10.1177/104063879801000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers T.D., Petrie L. A survey of vaccination practices against bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) virus in Saskatchewan dairy herds. Can. Vet. J. 1996;37:621–622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corapi W.V., French T.W., Dubovi E.J. Severe Thrombocytopenia in Young Calves Experimentally Infected with Noncytopathic Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus. J. Virol. 1989;63:3934–3943. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3934-3943.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David G.P., Crawshaw T.R., Gunning R.F., Hibberd R.C., Lloyd G.M., Marsh P.R. Severe disease in adult dairy cattle in three UK dairy herds associated with BVD virus infection. Vet. Rec. 1994;134:468–472. doi: 10.1136/vr.134.18.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaro N., Mari V., Lucente M.S., Sciarretta R., Moreno A., Armenise C., Losurdo M., Camero M., Lorusso E., Cordioli P., Buonavoglia C. Experimental infection of cattle, sheep and pigs with ‘Hobi’-like pestivirus. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;155:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaro N., Mari V., Pinto P., Lucente M.S., Sciarretta R., Cirone F., Colaianni M.L., Elia G., Thiel H.J., Buonavoglia C. Hobi-like pestivirus: both biotypes isolated from a diseased animal. J. Gen. Virol. 2012;93:1976–1983. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutskens F., Lamp B., Riedel C.M., Wentz E., Lochnit G., Doll K., Thiel H.-J., Rümenapf T. Vaccine-induced antibodies linked to bovine neonatal pancytopenia (BNP) recognize cattle major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) Vet. Res. 2011:42. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elber A.R., Stegeman A., Moser H., Ekker H.M., Smak J.A., Pluimers F.H. The classical swine fever epidemic 1997-1998 in The Netherlands: descriptive epidemiology. Prev. Vet. Med. 1999;42:157–184. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(99)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel B., Bouma A., Stegeman A., Buist W., Elbers A., Kogut J., Döpfer D., de Jong M.C.M. When can a veterinarian be expected to detect classical swine fever virus among breeding sows in a herd during an outbreak? Prev. Vet. Med. 2005;67:195–212. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourichon C., Beaudeau F., Bareille N., Seegers H. Quantification of economic losses consecutive to infection of a dairy herd with bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005;72:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzemeier J., Teuffert J., Greiser-Wilke I., Staubach C., Schlüter H., Moennig V. Epidemiology of classical swine fever in Germany in the 1990. Vet. Microbiol. 2000;77:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn G.J., Saatkamp H.W., Humphry R.W., Stott A.W. Assessing economic and social pressure for the control of bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005;72:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.08.012. discussion 215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessman B.E., Sjeklocha D.B., Fulton R.W., Ridpath J.F., Johnson B.J., McElroy D.R. Acute bovine viral diarrhea associated with extensive mucosal lesions, high morbidity, and mortality in a commercial feedlot. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2012;24:397–404. doi: 10.1177/1040638711436244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B., Depner K., Schirrmeier H., Beer M. A universal heterologous internal control system for duplex real-time RT-PCR assays used in a detection system for pestiviruses. J. Virol. Methods. 2006;136:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houe H. Economic impact of BVDV infection in dairies. Biologicals. 2003;31:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s1045-1056(03)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenckel M., Hoper D., Schirrmeier H., Reimann I., Goller K.V., Hoffmann B., Beer M. Mixed triple: allied viruses in unique recent isolates of highly virulent type 2 bovine viral diarrhea virus detected by deep sequencing. J. Virol. 2014;88:6983–6992. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00620-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A.M.Q., Adams M.J., Lefkowitz E., Carstens E.B. 1 edition. Elsevier; Oxford: 2011. Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; p. 1338. [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon S.R., Hill F.I., Reichel M.P., Brownlie J. Bovine viral diarrhoea: pathogenesis and diagnosis. Vet. J. 2014;199:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebler-Tenorio E.M., Kenklies S., Greiser-Wilke I., Makoschey B., Pohlenz J.F. Incidence of BVDV1 and BVDV2 Infections in Cattle Submitted for Necropsy in Northern Germany. J. Vet. Med. B. 2006;53:363–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2006.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebler E., Johannsen U., Pohlenz J. [The hemorrhagic form of acute bovine virus diarrhea: literature review and case report] Tierarztl. Prax. 1995;23:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R., Kühne S., Mansfeld R. Verlauf einer Herdeninfektion mit BVDV 2, Ein Fallbericht. Tierürztl. Prax. 2005;33:224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Moennig V. Introduction to classical swine fever: virus, disease and control policy. Vet. Microbiol. 2000;73:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moennig V., Houe H., Lindberg A. BVD control in Europe: current status and perspectives. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2005;6:63–74. doi: 10.1079/ahr2005102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obritzhauser W., Klemens F., Josef K. BVDV infection risk in the course of the voluntary BVDV eradication program in Styria/Austria. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005;72:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher P., HJT . Pestivirus (Flaviviridae) In: Tidona C., Darai G., editors. The Springer Index of Viruses. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin C., Vandenhurk J., Lecomte J., Tijssen P. Identification of a New Group of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus-Strains Associated with Severe Outbreaks and High Mortalities. Virology. 1994;203:260–268. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterhans E., Bachofen C., Stalder H., Schweizer M. Cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea viruses (BVDV): emerging pestiviruses doomed to extinction. Vet. Res. 2010:41. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presi P., Heim D. BVD eradication in Switzerland—A new approach. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;142:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presi P., Struchen R., Knight-Jones T., Scholl S., Heim D. Bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) eradication in Switzerland—experiences of the first two years. Prev. Vet. Med. 2011;99:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raulo S.M., Lyytikäinen T. Simulated detection of syndromic classical swine fever on a Finnish pig-breeding farm. Epidemiol. Infect. 2007;135:218–227. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebhun W.C., French T.W., Perdrizet J.A., Dubovi E.J., Dill S.G., Karcher L.F. Thrombocytopenia associated with acute bovine virus diarrhea infection in cattle. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1989;3:42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1989.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridpath J.F. BVDV genotypes and biotypes: practical implications for diagnosis and control. Biologicals. 2003;31:127–131. doi: 10.1016/s1045-1056(03)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridpath J.F., Bolin S.R. Delayed onset postvaccinal mucosal disease as a result of genetic recombination between genotype 1 and genotype 2 BVDV. Virology. 1995;212:259–262. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridpath J.F., Bolin S.R. The genomic sequence of a virulent bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) from the type 2 genotype: detection of a large genomic insertion in a noncytopathic BVDV. Virology. 1995;212:39–46. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridpath J.F., Neill J.D., Frey M., Landgraf J.G. Phylogenetic, antigenic and clinical characterization of type 2 BVDV from North America. Vet. Microbiol. 2000;77:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridpath J.F., Neill J.D., Vilcek S., Dubovi E.J., Carman S. Multiple outbreaks of severe acute BVDV in North America occurring between 1993 and 1995 linked to the same BVDV2 strain. Vet. Microbiol. 2006;114:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaarschmidt U., Schirrmeier H., Strebelow G., Wolf G. [Detection of border disease virus in a sheep flock in Saxony] Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. 2000;113:284–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirrmeier H. Bremen e.V., Mitteilungsblatt des ganzen Nordens; Landesverband Niedersachsen: 2013. Auftreten von akuten Infektionen mit BVDV-2c in Deutschland. Mitteilungsblatt des ganzen Nordens/BPT-Bundesverband Praktizierender Tierärzte; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schirrmeier H. Three years of mandatory BVDV control in Germany–lessons to be learned. Proc. XXVIII World Buiatric Congress; Cairns Australia; 2014. pp. 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs D.W., Fleming S.A., Maslin W.R., Groce A.W. Osteopetrosis, Anemia, Thrombocytopenia, and Marrow Necrosis in Beef-Calves Naturally Infected with Bovine Virus Diarrhea Virus. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1995;7:555–559. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stähl K., Alenius S. 2012. BVDV control and eradication in Europe—an update. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffregen B., Bolin S.R., Ridpath J.F., Pohlenz J. Morphologic lesions in type 2 BVDV infections experimentally induced by strain BVDV2-1373 recovered from a field case. Vet. Microbiol. 2000;77:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima M., Frey H.-R., Yamato O., Maede Y., Moennig V., Scholz H., Greiser-Wilke I. Prevalence of genotypes 1 and 2 of bovine viral diarrhea virus in Lower Saxony, Germany. Virus Res. 2001;76:31–42. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(01)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel W. Kasuitischer Beitrag zu hämorrhagischen Diathesen bei Kälbern mit BVD-Virusinfektion. Tierarztl. Prax. 1993;21:413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfmeyer A., Wolf G., Beer M., Strube W., Hehnen H.R., Schmeer N., Kaaden O.R. Genomic (5'UTR) and serological differences among German BVDV field isolates. Arch. Virol. 1997;142:2049–2057. doi: 10.1007/s007050050222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz H., Altan E., Ridpath J., Turan N. Genetic diversity and frequency of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) detected in cattle in Turkey. Comp. Immunol. Microb. 2012;35:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]