Abstract

A mechanical perturbation method that locally restricts conformational entropy along the protein backbone is used to identify putative allosteric sites in a series of antibody fragments. The method is based on a distance constraint model that integrates mechanical and thermodynamic viewpoints of protein structure wherein mechanical clamps that mimic substrate or cosolute binding are introduced. Across a set of six single chain-Fv fragments of the anti-lymphotoxin-β receptor antibody, statistically significant responses are obtained by averaging over 10 representative structures sampled from a molecular dynamics simulation. As expected, the introduced clamps locally rigidify the protein, but long-ranged increases in both rigidity and flexibility are also frequently observed. Expanding our analysis to every molecular dynamics frame demonstrates that the allosteric responses are modulated by fluctuations within the hydrogen-bond network where the native ensemble is comprised of conformations that both are, and are not, affected by the perturbation in question. Population shifts induced by the mutations alter the allosteric response by adjusting which hydrogen-bond networks are the most probable. These effects are compared using response maps that track changes across each single chain-Fv fragment, thus providing valuable insight into how sensitive allosteric mechanisms are to mutations.

Introduction

Allostery (1) is the process by which proteins transmit the effect of binding at one site over long distances. Due to its biochemical and therapeutic importance, allostery remains a central focus in molecular biology. Progress has been made both experimentally (2, 3) and theoretically (4, 5, 6) to describe the physical processes leading to allostery, but exact molecular mechanisms remain elusive. Recent studies (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) revealed that allostery can also be associated with the changes in dynamics and large-scale conformational disorder. These studies challenge the traditional molecular-wire views of allostery and provide a framework to describe allostery in structured, dynamic, and disordered systems. For example, Tsai and Nussinov (13) integrated three different allosteric standpoints (i.e., thermodynamics, free energy landscape, and structure), which led to the conclusion that allosteric coupling does not determine allosteric efficacy. These studies emphasize the ensemble nature of allostery, where ligand binding does not create a new conformational state; rather, it shifts the population among the existing states. By extension, mutation can affect the allosteric response by similarly shifting the population of active conformational states.

Various computational methods have been developed to investigate the physical mechanism of protein allostery. Methods based on molecular-dynamics (MD) simulation (14, 15, 16) have been employed to predict allosteric sites. However, these methods are computationally expensive, especially in large protein systems. Several models (17, 18, 19, 20, 21) have also been developed based on the protein native-state topology to identify allosteric sites more quickly than MD. Ming and Wall (22, 23) developed a perturbation-based method based on elastic network models (24) to identify allosteric binding sites. They perturbed different regions of the protein by mimicking ligand binding across the protein, and then identified where the ligand binding induces large changes in conformational dynamics. Recently, Erman (25) developed a method to evaluate the effects of ligand binding on the stiffness of proteins, again based upon an elastic network model. We developed a perturbation method (26) based on our distance constraint model (DCM) (27) that integrates both the thermodynamical and the mechanical viewpoints. Our mechanical perturbation method (MPM) introduces mechanical constraints in conceptually similar ways to the above methods, and then the thermodynamic and mechanical properties are recalculated. Regions that lead to large changes in the mechanical and/or thermodynamic properties are identified as allosteric (28). Applying the MPM to three bacterial chemotaxis protein Y orthologs (26) recapitulated the importance of a loop region known to relay the phosphorylation allosteric signal. Moreover, our results demonstrated that while some evolutionary conservation is present, allosteric response is very sensitive to sequence divergence. This result is consistent with a growing appreciation for the sensitivity of allosteric mechanisms (29).

In two of our previous reports (30, 31), we demonstrated how a single point mutation can substantively affect the rigidity/flexibility equilibrium within the native state ensemble. Across a set of 14 structurally diverse human C-type lysozyme point mutants (30) and a set of six single chain-Fv (scFv) antibody fragments (31) of the anti-lymphotoxin-β receptor antibody, we observe that long-ranged changes in protein rigidity and flexibility are common. Using the same dataset of scFv antibody fragments (31), we now reveal how the stabilizing mutations that conserve wild-type binding affinity alter allosteric response. Applying the MPM to the antibody fragments, statistically significant allosteric responses are obtained by averaging over 10 representative structures sampled from a molecular dynamics simulation. We observe that the allosteric responses are modulated by the mutation due to population shifts within the hydrogen-bond network (HBN) ensemble at equilibrium. As expected, the introduced mechanical clamps cause large increases in rigidity locally; however, long-ranged changes in rigidity and flexibility are also observed. In an individual protein, certain conformations will have stronger allosteric signals than others, depending upon the underlying HBN. For example, it is common for as many as 90% of the conformations to relay the binding signal at an allosteric site. Mutations that significantly change HBN populations are likely to alter the allosteric response. In the antibody fragments characterized here, position 181 is found to always initiate an allosteric response across all six fragments, whereas position 55 may or may not be allosteric, depending upon which sequence is considered.

Materials and Methods

The distance constraint model

Thermodynamic and mechanical properties of proteins are characterized by the DCM, which combines all-atom free-energy decomposition with constraint theory. The native structure is mapped onto constraint topology, where the vertices of the graph represent atoms, and edges describe intermolecular interactions. A Pebble Game (PG) algorithm (32, 33) is used to identify the overconstrained/rigid, isostatic, and flexible regions, which elucidate a nonadditivity through intermolecular couplings (34). The PG algorithm is an athermal formulation because it does not consider constraint fluctuations in the network. The DCM introduces thermal fluctuations into the network rigidity paradigm. Specifically, the DCM considers a Gibbs ensemble of PG graphs, where each constraint is associated with an enthalpic and entropic contribution. The total enthalpy of a network is the sum over enthalpy contributions from all distance constraints present, whereas the total entropy is the sum over only the independent distance constraints, being nonadditive (35) in nature.

As applied to proteins (36, 37), the number of nativelike torsion constraints, , and number of H-bond constraints, , specifies a macrostate. Native torsion constraints have lower energy and lower entropy relative to disordered torsion constraints, meaning they correspond to good packing interactions. Together, the model describes protein stability in terms of atomic packing and the HBN (note: salt bridges are considered to be a special case of H-bond). A free energy functional is defined for each macrostate by:

| (1) |

where U is the total energy of the HBN, is an average H-bond energy between protein to solvent, is the energy of a nativelike torsion, is the conformational entropy, and is the mixing entropy of the macrostate associated with the number of ways of distributing native-torsions and H-bonds within the protein. To account for nonadditivity in conformational entropy, , is calculated over the set of independent constraints using:

| (2) |

where the index t is over the full set of H-bonds that are identified from the input (crystal) structure; is the entropy of H-bond t; and , respectively, are the entropy values of a nativelike and disordered torsion constraint; and is the total number of disorder torsion angles. Note that equals the total number of rotatable dihedral angles.

The values are conditional probabilities for a constraint i to be independent when present. For a given framework, the PG is used to calculate , where constraints added to flexible regions are assigned = 1 and constraints added to already rigid regions are assigned = 0 because all degrees of freedom (DOF) have already been removed. The DCM obtains the lowest possible upper bound limit on the conformational entropy by preferentially placing constraints with the lowest entropy first. In other words, it sums entropies over a minimal set of the most constructive yet independent interactions. By Monte Carlo sampling over topological frameworks within a given macrostate, the final values are averaged. Because of the degeneracy in the native and disordered torsion parameters, it follows that for native torsions and for disordered torsions. These simplifications are reflected in Eq. 2, but the Monte Carlo sampling is done for each torsion constraint individually. Typically, 200 samples per macrostate is a sufficient number for good statistics.

H-bond energies are calculated from an empirical potential (26). The entropic cost to form an independent H-bond, γt, is linearly related to its potential well depth (36). The value of and the linear relationship between H-bond energy and entropy have been established in prior works (37), whereas , , and are phenomenological parameters determined by fitting to experimental data, such as heat capacity.

Mechanical response

The flexibility index (FI) is one metric used to characterize the rigidity/flexibility profile of a protein along its backbone. For a given framework, the PG algorithm identifies each rotatable bond as: 1) flexible if it is in an underconstrained region; 2) isostatic if it is just-enough-constrained to be rigid; or 3) redundant if it is in an overconstrained region. Each bond is assigned a flexibility index, , defined based on a single constraint network as follows. If the bond in question is part of an isostatically rigid region, = 0. If the bond in question is part of a flexible region, the number of rotatable bonds within that flexible region is counted, and denoted as H. The number of independent disordered torsions within that same flexible region is also counted, and denoted as A. To represent the density of independent DOF within the flexible region, the value = is assigned to all rotatable bonds within this cluster. Conversely, if the bond in question is part of an overconstrained region, the number of rotatable bonds is counted and denoted as D, and the number of redundant constraints within that region is also counted and denoted as B. The value represents the density of redundant constraints within the overconstrained region, and it is assigned to all rotatable bonds within this cluster. Once this counting is complete, every rotatable bond in the protein will have a value assigned to it. To distinguish between densities of DOF versus redundant constraints, the values corresponding to the flexible regions are positive, and those for overconstrained regions are negative.

MD simulation and clustering method

We use MD simulation to generate an ensemble of conformations for subsequent DCM analysis across a set of representative structures. A 100-ns simulation trajectory is generated for each mutant and wild-type protein with GROMACS 4.5.5 (38). The MD simulation protocol is discussed in our prior article (31). While the DCM residue-residue cooperativity information is sensitive to one input structure, it was shown (31) that averaging over 10 representative structures yields robust results. Consistency of the results suggests longer MD simulations and replicas are not necessary because large changes in the HBN do not occur in the native state. Two-thousand evenly spaced frames from each trajectory are clustered on root-mean-squared displacement (RMSD) using the KCLUST (39) module of the MMTSB (40) tool set. Ten representative structures are obtained from the 10 largest clusters, representing 77–95% of the conformations. A representative structure is identified as the structure closest to the centroid from each of these 10 largest clusters. After MD simulation and clustering, hydrogen atoms are added to each of the 10 representative structures by using H++ server (41). Each of the 10 representative structures is then energy-minimized and used as DCM input. An average of all DCM properties is taken over the 10 representative structures.

Dataset and model parameters

From prior work (31) we use the same six scFv anti lymphotoxin-β receptors (42), modeled from the wild-type Fab structure (PDB: 3HC0) and five stabilizing mutations that conserve binding affinity as identified by Miller et al. (43) from an experimental library screening essay. The mutations are (V56G), (P104D), (S16E, S177L), (S16E, V56G, S177L), and (S16E, V56G, P104D, S177L) based on PDB sequence numbering that correspond to (VH V55G), (VH P101D), (VH S16E; VL S46L), (VH S16E, V55G; VL S46L), and (VH S16E, V55G, P101D; VL S46L), respectively, in the Kabat sequence alignment scheme that was employed previously in Li et al. (31).

The model parameters (, , ) were obtained by fitting to the experimental heat capacity curve obtained from the differential scanning calorimetry. We use the same set of parameters (31) i.e., = −2.71 kcal/mol, = −0.89 kcal/mol, and = 1.89, obtained by fitting the structure corresponding to P104D to its Cp curve (43). The same model parameters are then applied to all representative structures for the wild-type and for all mutations.

Mechanical perturbation method

To study the allosteric response, we employ the MPM (26). The MPM introduces quenched torsion constraints as a mechanical perturbation to induce change in mechanical and thermodynamical properties. Previously (26), we placed torsion constraints to fix the , ψ-, and χi-dihedral angles in a target residue. Mechanical and thermodynamic properties of the perturbed input structure are recalculated per target residue and changes in these properties are calculated with respect to the unperturbed structure to define the response to the perturbation. Note that with just the x-ray crystal structure, a window size of 1, 3, and 5 gave essentially the same results. Here, the mechanical perturbation window size is increased to three consecutive residues having a total of nine constraints. Averaging over different sets of 10 MD frames required a minimum window size of 3 to obtain robust results, and a window size of 5 gives essentially the same results. Using the same rationale as before, we select the smallest possible window size that yields a robust signal to give the minimum perturbation possible to the structure. We applied clamping sequentially from the N-terminus to the C-terminus of a protein. Mechanical and thermodynamic response is calculated for each perturbation window. After each residue is targeted, the outliers within the statistics of the response in stability and flexibility profiles are identified as putative allosteric sites.

The DCM provides information about protein stability and flexibility that we collectively refer to as quantified stability/flexibility relationships. Here, we track two quantified stability/flexibility relationship properties: ΔΔG, and correlation in the flexibility index (cFI). Specifically, ΔΔG equals , where ΔG is the difference in free energy between the native and unfolded basins. Large changes in ΔΔG correspond to an allosteric response associated with a thermodynamic population shift. The quantity cFI is the Pearson correlation coefficient between the perturbed and unperturbed structures. That is, if cFI = 1 there is no change in flexibility/rigidity profile across the whole protein structure under the perturbation, whereas cFI < 1 identifies a putative allosteric site due to readjustments in the rigidity/flexibility profile. Box plots for ΔΔG and cFI are compared from one representative structure to another as shown in Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material. This analysis reveals that the cFI response function gives good sequence difference discrimination, whereas ΔΔG does not. As such, from this point on, we only compare mutation effects in terms of changes in flexibility/rigidity.

Results and Discussion

Mutation effects on allosteric response

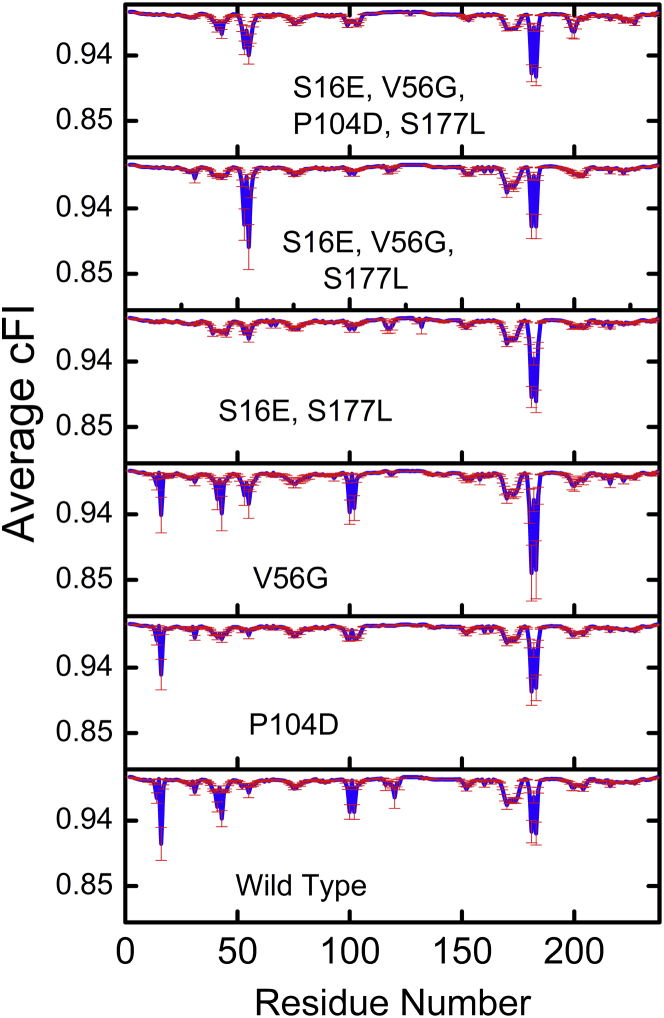

The mechanical response (cFI) of each representative structure for all six scFv antibody fragments are shown in Fig S2, a–f. Quantitative differences occur across the set of representative structures in each case, which is due to changes in the underlying HBNs associated with the different conformations. Nevertheless, conserved signals are also observed. Fig. 1 averages over the set of 10 representative structures in each mutant. A response must be greater than the standard error to be counted. Therefore, the raw cFI scores are converted to statistical z-scores (see Fig. S3) and mapped to structure shown in Fig. 2. For each of the scFv antibody fragment structures it is observed that the majority of putative allosteric sites that lead to a statistically significant change in flexibility/rigidity arise in the VL domain of the antibody fragment, and in particular the CDR L1 loop. A summary of putative allosteric site counts is given in Table S1 in the Supporting Material.

Figure 1.

Average mechanical response (cFI) of six scFv fragments. The cFI is averaged over 10 representative structures, corresponding to each of the 10 largest structural clusters from a 100-ns molecular-dynamics simulation trajectory. The error bars shown in red represent the standard error in cFI data across a set of 10 representative structures. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 2.

Average cFI data for all six scFv fragments are mapped to structure. Each scFv fragment has two domains: (left side) VH domain; (right side) VL domain. The mutations are shown by arrows and by yellow in the cartoon representations. The average cFI data for all six proteins are converted into statistical z-scores. Green corresponds to the putative allosteric sites with z-scores in between −1 and −2. Red corresponds to the putative allosteric sites with a statistical z-score >−2. To see this figure in color, go online.

A large number of allosteric responses are observed in the wild-type (WT) fragment, some of which are conserved or partially conserved across the five mutants. For example, large allosteric responses are observed in the WT at sites 16, 41, 100, 102, 181, and 183 (compare to Fig. 1). Comparing these particular sites across the mutants reveals that only allosteric sites 181 and 183 are conserved across all six fragments. Allosteric response at perturbation sites 16 and 102 are conserved in both single mutants (V56G and VH P104D). Further, signals at 41 and 102 are also present in V56G. Interestingly, it is observed that allosteric response is qualitatively conserved across the WT and V56G mutant. Similarly, the allosteric response in the triple and quadruple mutants are also qualitatively pairwise conserved. We find that the P104D mutant significantly suppresses allosteric response relative to the WT, including at positions far away from the mutation site. Interestingly, adding the same P104D mutation to the triple mutant has no dramatic attenuating affect in the quadruple mutant. In contrast, the presence of allosteric signals at sites 52 and 54 coincide with the occurrence of the V56G mutation, which, along with one of the single mutants, is present in the triple and quadruple mutants. Sites 52 and 54 are the only significant allosteric responses not also observed in the WT. These results highlight the complex and context-dependent nature of allosteric response, obfuscating simple mechanistic explanations.

Fluctuations within the hydrogen-bond network

The DCM is fundamentally sensitive to the HBNs, and therefore the observed difference in allosteric response must emerge from differences therein. For computational tractability, the above section compared only 10 representative structures. However, we now expand to all 2000 evenly spaced frames to understand how fluctuations within the HBN affect the allosteric response in three example sites taken from Fig. 1. The three cases selected correspond to sites without an allosteric signal (site 90), a weak signal (site 170), and a strong signal (site 181) that is conserved across all six scFv structures. Fig. 3 shows the variation of mechanical response across the MD trajectory for three perturbation sites in the WT and quadruple mutant. There is no signal in either mutant throughout the trajectory for the site-90 example. Conversely, there are moderate and strong signals in ∼90% of the frames for the other two, meaning 10% of the conformations are not allosteric at those sites. Moreover, Fig. 4 A shows the response for site 55 for all mutants. Note that there is no allosteric response at sites in the WT, but the mutants show varying degree of fluctuation in allosteric response. Recasting these results as distributions in Fig. 4 B, large population shifts are observed in all three of the mutants that contain V56G. The WT and P104D distributions are sharp because allosteric signals are rarely observed across the MD trajectory. These results underscore the probabilistic nature of allostery and highlight how fluctuations within the HBN modulate allosteric response.

Figure 3.

Variation of mechanical allosteric signal (cFI) at perturbation sites 90 (red), 170 (blue), and 181 (black) across all 2000 MD frames for (A) wild-type and (B) quadruple mutants. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 4.

(A) Variation of mechanical allosteric signal (cFI) at perturbation site 55 across all 2000 MD frames for all six scFv fragments. (B) Probability distribution plotted against the cFI data of all six scFv fragments. To see this figure in color, go online.

Representative structure sensitivity

We used 10 representative structures in the first section, corresponding to the 10 largest structural clusters to represent each mutant. However, the results in the previous section highlight significant structural sensitivity, leading to a question of sampling bias. That is, are the 10 representative structures truly representative of the full trajectory? To address this point, we randomly select sets of structures from the MD trajectory ranging from 10 to 100. Averaging over 1000 random sets in each case, Fig. S4 shows box plots for the distribution of cFI responses for the quadruple mutant perturbed at site 55. In each case, the median is conserved and the variance is reduced as more structures are averaged over. Moreover, the mean response is readily obtained using 10 randomly selected structures, indicating the RMSD clustering process is unnecessary because the fluctuations in allosteric signals are a reflection of equilibrium fluctuations in the HBN with no apparent correlation with RMSD. The rapid convergence in allosteric response across conformations in the native state ensemble not only keeps the MPM computationally efficient, it points to why probabilistic aspects of allostery are easily overlooked.

Redistribution of rigidity and flexibility upon mutation

Our prior works have extensively evaluated how sequence variations lead to redistributions within rigidity and flexibility in antibody fragments (31, 44, 45). Interestingly, thermostabilizing mutations often locally rigidify the protein due to local optimization of the HBN, while the entropic cost of this rigidification is offset by a corresponding increase in flexibility in regions far removed from the mutation. These long-ranged responses are central to the allosteric responses we are tracking here. However, as a global quantity, the cFI metric does not indicate where the response occurs along the backbone of protein. To monitor the response in detail, we directly work with the response ΔFI, which is the difference between the flexibility index along the backbone of the perturbed and unperturbed structures. As a consequence, clamping at different sites results in a set of ΔFI values corresponding to every perturbation site in the protein. Negative ΔFI values correspond to increased rigidity within the perturbed protein, whereas positive values correspond to increased flexibility.

Focusing again on perturbation site 181, Fig. 5 shows the ΔFI values for all six scFv fragments averaged over all 2000 frames, which is qualitatively the same result obtained using 10 representative structures as described in the first section or any 10 random selections (data not shown). As expected, there is a strong rigidification near the perturbation site. However, there are many responses—both increased rigidity and increased flexibility at other sites throughout the protein. While Fig. S4 mitigates some of the concern, the question regarding how well the 10 representative structures describe ΔFI results across the full MD trajectory is important considering the high levels of fluctuations that are present. To answer this, ΔFI response matrices (compare to Fig. 6) provide the full set of mechanical responses for a given scFv fragment and perturbation site. Therein, the change in ΔFI at each position across all 2000 evenly spaced frames is plotted. The raw ΔFI values have been thresholded between ±1. The perturbed structure is strongly rigidified at sites where ΔFI −0.05 (blue color), whereas it is strongly more flexible at sites where ΔFI +0.05 (red color). Intervening colors correspond to marginal responses. As in Fig. 5, a strong local rigidification is again observed near the perturbation site, but long-ranged mechanical changes are also observed that include significant increases in flexibility. HBN fluctuations cause the strength of those increased flexibility responses to vary significantly across the ensemble. It is clear that the overall pattern of response is well conserved across the MD trajectory.

Figure 5.

Average variation of change in flexibility index (ΔFI) at allosteric signal site 181 for all six scFv fragments. The ΔFI data is averaged over all 2000 frames in the MD trajectory. The break in ΔFI response corresponds to perturbed residue positions. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 6.

Change in the flexibility index (ΔFI) across all 2000 MD frames for the triple mutant at allosteric signal position 55. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 7 maps the ΔFI response for site 181 across the full 2000 frames to structure, where red corresponds to increases in flexibility and blue corresponds to increased rigidity. Typically the VH domain is rigidified due to the perturbation, whereas the VL domain becomes more flexible. Fig. 8 shows the same metrics for perturbation site 55, which has more variation across the six scFv fragments, corresponding to the strong sequence-dependence in this example. In both cases, the redistribution of rigidity and flexibility upon perturbation described in Figs. 5 and 6 is structurally visualized, stressing the long-ranged nature of the responses to these local binding events.

Figure 7.

Average change in flexibility index (ΔFI) across all 2000 MD frames at perturbation site 181 is shown in color-coded structures for all six scFv fragments. The perturbation sites in all six scFv structures are shown in green whereas the mutation sites are shown in yellow in the cartoon representation. The blue region corresponds to the increases in rigidity that accompanies the clamping at site 181, whereas red indicates increased flexibility. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 8.

The average of change in flexibility index (ΔFI) across all 2000 MD frames at perturbation position 55 is shown in color-coded structures for all six ScFv fragments. The perturbation sites in all six scFv structures are shown in green whereas the mutation sites are shown in yellow in the cartoon representation. The blue region corresponds to the increases in rigidity that accompanies the clamping at site 55, whereas red indicates increased flexibility. To see this figure in color, go online.

Relationship to experimental characterizations

Unfortunately, there is currently no experimental data that directly connects to allostery in this dataset. In general, the DCM has agreed well to diverse experiment results in the past, including the MPM employed here. As discussed above, the MPM correctly identifies the phosphorylation site as allosteric in three chemotaxis protein Y orthologs (26), which is the only conserved site identified across the set. As with the MPM results, our collective results reveal CC to be very sensitive to sequence and structural variations across protein families (28, 30, 31, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50), which is in complete agreement with various experimental comparisons of allosteric effects across protein families. Going as far back as 1970 (51), quantifiable differences in allosteric response have been used as a taxonomic marker in the 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthetase family. Further, mechanistic differences are even observed in hemoglobin (52, 53), which is the textbook model of long-range intramolecular communication within protein structures. In fact, simply replacing one active-site divalent cation for another (Mg2+→Mn2+) in human liver pyruvate kinase completely changes the magnitude of allosteric activation by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and inhibition by alanine (54). Clearly, our observation that allosteric response is sensitive to mutation should not be surprising given this context.

If we focus specifically on backbone flexibility (FI), we can conclude the same. Several years ago, we demonstrated that FI values correlate well (R > 0.8) to both nuclear magnetic resonance S2 order parameters and x-ray crystal structure B-factors (37). Similarly, our FI results have also been shown to be consistent with H/D exchange data in multiple systems (37, 46). Impressively, the DCM is also able to accurately reproduce experimental Tm values with percent errors of 4.3% across a set of 15 lysozyme mutants (55) and 1.1% across this set of Fv fragments (31). Despite the relatively minor changes to the overall three-dimensional structure introduced by these point mutants, the DCM predicts allosteric response based on significant changes in backbone dynamics, which is found to be very sensitive to mutation. There is again considerable experimental support for this in other systems (56, 57, 58), further supporting the magnitude and frequency of the changes we observe here.

Conclusions

The results presented here underscore the importance of equilibrium fluctuations within the native-state basin on allosteric responses. Specifically, fluctuations within the HBN lead to large differences in the ability of a particular site to initiate an allosteric response or not. As the HBN changes, the ability of a particular binding event to be felt at remote sites changes. As argued previously by Motlagh et al. (7) and Tsai et al. (8), this means that allosteric responses are best described as probabilistic events. Put otherwise, the mechanical connections present within the HBN undergo statistical fluctuations that are governed by thermodynamics, which affects all aspects of protein structure, including allostery. Based on the small number of mechanical perturbations introduced at each site, these results demonstrate that even the smallest binding events can lead to significant rigidity/flexibility redistribution. Applied to six antibody scFv fragments, our MPM results also highlight how mutations change the allosteric response through changes in the HBNs. Most of the mutant-induced changes relative to the WT antibody lead to reduced allosteric signals. However, allostery at sites 52 and 55 is only observed in the mutants that contain the V56G mutation.

The allosteric response due to the MPM captures a general phenomenon that can be viewed more broadly. For example, the addition or removal of a disulfide bond will modulate the MPM response. In an early application of the DCM, it was predicted that a mesophilic and thermophilic ortholog of ribonuclease H (46) will respond very differently to a strategically placed disulfide bond. Recently, the MD/DCM protocol was applied to chemokine CXCL7 (59) to elucidate how the HBN changes in response to removing disulfide bonds. Because a change in the HBN induces change in protein dynamics, the MPM compliments molecular stapling experiments (60) that involve engineering a disulfide bridge. As part of the motivation for this work, preferential binding of cosolutes to specific sites will alter allostery maps as various cosolute concentrations in a multicomponent solvent modify binding affinities.

Author Contributions

D.R.L. and D.J.J. designed the research; A.S. performed research; A.S., D.R.L., and D.J.J. analyzed data; and A.S., M.B.T., S.U., J.C.-F., D.R.L., and D.J.J. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

Support for Dr. Amit Srivastava is provided by a grant from MedImmune LLC.

Key to the distance constraint model is the use of graph-rigidity algorithms, claimed in U.S. Patent 6,014,449, which has been assigned to the Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Used with permission.

Editor: Michele Vendruscolo.

Footnotes

Four figures and one table are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30116-3.

Contributor Information

Dennis R. Livesay, Email: drlivesa@uncc.edu.

Donald J. Jacobs, Email: djacobs1@uncc.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Nussinov R., Tsai C.J. Allostery in disease and in drug discovery. Cell. 2013;153:293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perutz M.F., Rossmann M.G., North A.C.T. Structure of haemoglobin: a three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 5.5 Å resolution, obtained by x-ray analysis. Nature. 1960;185:416–422. doi: 10.1038/185416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzeng S.R., Kalodimos C.G. Protein dynamics and allostery: an NMR view. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011;21:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nussinov R., Tsai C.J., Ma B. The underappreciated role of allostery in the cellular network. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013;42:169–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton A.W. Allostery: an illustrated definition for the ‘second secret of life’. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Changeux J.P. Allostery and the Monod-Wyman-Changeux model after 50 years. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2012;41:103–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motlagh H.N., Wrabl J.O., Hilser V.J. The ensemble nature of allostery. Nature. 2014;508:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nature13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai C.J., Del Sol A., Nussinov R. Protein allostery, signal transmission and dynamics: a classification scheme of allosteric mechanisms. Mol. Biosyst. 2009;5:207–216. doi: 10.1039/b819720b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petit C.M., Zhang J., Lee A.L. Hidden dynamic allostery in a PDZ domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18249–18254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904492106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tzeng S.R., Kalodimos C.G. Protein activity regulation by conformational entropy. Nature. 2012;488:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature11271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tzeng S.R., Kalodimos C.G. Dynamic activation of an allosteric regulatory protein. Nature. 2009;462:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature08560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daily M.D., Gray J.J. Allosteric communication occurs via networks of tertiary and quaternary motions in proteins. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai C.J., Nussinov R. A unified view of “how allostery works”. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivetac A., McCammon J.A. A molecular dynamics ensemble-based approach for the mapping of druggable binding sites. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;819:3–12. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-465-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClendon C.L., Friedland G., Jacobson M.P. Quantifying correlations between allosteric sites in thermodynamic ensembles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:2486–2502. doi: 10.1021/ct9001812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharp K., Skinner J.J. Pump-probe molecular dynamics as a tool for studying protein motion and long range coupling. Proteins. 2006;65:347–361. doi: 10.1002/prot.21146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chennubhotla C., Bahar I. Markov propagation of allosteric effects in biomolecular systems: application to GroEL-GroES. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2:36. doi: 10.1038/msb4100075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haliloglu T., Erman B. Analysis of correlations between energy and residue fluctuations in native proteins and determination of specific sites for binding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:088103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.088103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atilgan C., Gerek Z.N., Atilgan A.R. Manipulation of conformational change in proteins by single-residue perturbations. Biophys. J. 2010;99:933–943. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoh K., Sasai M. Statistical mechanics of protein allostery: roles of backbone and side-chain structural fluctuations. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134:125102–125119. doi: 10.1063/1.3565025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai C.J., Kumar S., Nussinov R. Folding funnels, binding funnels, and protein function. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1181–1190. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.6.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ming D., Wall M.E. Allostery in a coarse-grained model of protein dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;95:198103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.198103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ming D., Wall M.E. Quantifying allosteric effects in proteins. Proteins. 2005;59:697–707. doi: 10.1002/prot.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haliloglu T., Bahar I., Erman B. Gaussian dynamics of folded proteins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;79:3090. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erman B. A fast approximate method of identifying paths of allosteric communication in proteins. Proteins. 2013;81:1097–1101. doi: 10.1002/prot.24284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mottonen J.M., Jacobs D.J., Livesay D.R. Allosteric response is both conserved and variable across three CheY orthologs. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2245–2254. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobs D.J., Dallakyan S., Heckathorne A. Network rigidity at finite temperature: relationships between thermodynamic stability, the nonadditivity of entropy, and cooperativity in molecular systems. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2003;68:061109. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.061109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs D.J., Livesay D.R., Verma D. Ensemble properties of network rigidity reveal allosteric mechanisms. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;796:279–304. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-334-9_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishwar A., Tang Q., Fenton A.W. Distinguishing the interactions in the fructose 1,6-bisphosphate binding site of human liver pyruvate kinase that contribute to allostery. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1516–1524. doi: 10.1021/bi501426w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verma D., Jacobs D.J., Livesay D.R. Changes in lysozyme flexibility upon mutation are frequent, large and long-ranged. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li T., Tracka M.B., Livesay D.R. Redistribution of flexibility in stabilizing antibody fragment mutants follows Le Châtelier’s principle. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs D.J., Rader A.J., Thorpe M.F. Protein flexibility predictions using graph theory. Proteins. 2001;44:150–165. doi: 10.1002/prot.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs D.J., Thorpe M.F. Generic rigidity percolation: the pebble game. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995;75:4051–4054. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Istomin A.Y., Gromiha M.M., Livesay D.R. New insight into long-range nonadditivity within protein double-mutant cycles. Proteins. 2008;70:915–924. doi: 10.1002/prot.21620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vorov O.K., Livesay D.R., Jacobs D.J. Nonadditivity in conformational entropy upon molecular rigidification reveals a universal mechanism affecting folding cooperativity. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1129–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs D.J., Dallakyan S. Elucidating protein thermodynamics from the three-dimensional structure of the native state using network rigidity. Biophys. J. 2005;88:903–915. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livesay D.R., Dallakyan S., Jacobs D.J. A flexible approach for understanding protein stability. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Berendsen H.J.C. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karpen M.E., Tobias D.J., Brooks C.L., 3rd Statistical clustering techniques for the analysis of long molecular dynamics trajectories: analysis of 2.2-ns trajectories of YPGDV. Biochemistry. 1993;32:412–420. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feig M., Karanicolas J., Brooks C.L., 3rd MMTSB Tool Set: enhanced sampling and multiscale modeling methods for applications in structural biology. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2004;22:377–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon J.C., Myers J.B., Onufriev A. H++: a server for estimating pKas and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W368–W371. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jordan J.L., Arndt J.W., Lugovskoy A. Structural understanding of stabilization patterns in engineered bispecific Ig-like antibody molecules. Proteins. 2009;77:832–841. doi: 10.1002/prot.22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller B.R., Demarest S.J., Glaser S.M. Stability engineering of scFvs for the development of bispecific and multivalent antibodies. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2010;23:549–557. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li T., Tracka M.B., Livesay D.R. Rigidity emerges during antibody evolution in three distinct antibody systems: evidence from QSFR analysis of Fab fragments. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li T., Verma D., Jacobs D.J. Thermodynamic stability and flexibility characteristics of antibody fragment complexes. Protein Pept. Lett. 2014;21:752–765. doi: 10.2174/09298665113209990051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Livesay D.R., Jacobs D.J. Conserved quantitative stability/flexibility relationships (QSFR) in an orthologous RNase H pair. Proteins. 2006;62:130–143. doi: 10.1002/prot.20745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mottonen J.M., Xu M., Livesay D.R. Unifying mechanical and thermodynamic descriptions across the thioredoxin protein family. Proteins. 2009;75:610–627. doi: 10.1002/prot.22273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verma D., Jacobs D.J., Livesay D.R. Variations within class-A β-lactamase physiochemical properties reflect evolutionary and environmental patterns, but not antibiotic specificity. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown M.C., Verma D., Livesay D.R. A case study comparing quantitative stability-flexibility relationships across five metallo-β-lactamases highlighting differences within NDM-1. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1084:227–238. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-658-0_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown J.R., Livesay D.R. Flexibility correlation between active site regions is conserved across four AmpC β-lactamase enzymes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jensen R.A., Stenmark S.L. Comparative allostery of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthetase as a molecular basis for classification. J. Bacteriol. 1970;101:763–769. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.3.763-769.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Royer W.E., Jr., Knapp J.E., Heaslet H.A. Cooperative hemoglobins: conserved fold, diverse quaternary assemblies and allosteric mechanisms. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:297–304. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01811-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Royer W.E., Jr., Zhu H., Knapp J.E. Allosteric hemoglobin assembly: diversity and similarity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27477–27480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fenton A.W., Alontaga A.Y. The impact of ions on allosteric functions in human liver pyruvate kinase. Methods Enzymol. 2009;466:83–107. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)66005-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verma D., Jacobs D.J., Livesay D.R. Predicting the melting point of human C-type lysozyme mutants. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2010;11:562–572. doi: 10.2174/138920310794109210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee H.J., Yoon Y.J., Lee H.C. 15N NMR relaxation studies of Y14F mutant of ketosteroid isomerase: the influence of mutation on backbone mobility. J. Biochem. 2008;144:159–166. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wen Y., Li J., Lin D. Solution structure and dynamics of the I214V mutant of the rabbit prion protein. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan X., Werner J.M., Downing A.K. Effects of the N2144S mutation on backbone dynamics of a TB-cbEGF domain pair from human fibrillin-1. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;316:113–125. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Herring C.A., Singer C.M., Nesmelova I.V. Dynamics and thermodynamic properties of CXCL7 chemokine. Proteins. 2015;83:1987–2007. doi: 10.1002/prot.24913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moleschi K.J., Akimoto M., Melacini G. Measurement of state-specific association constants in allosteric sensors through molecular stapling and NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:10777–10785. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.