Abstract

The H1 haplotype of the microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) is associated with an increased risk of Parkinson disease (PD) compared with the H2 haplotype, but its effect on Lewy body (LB) formation is unclear. In this study, we compared the MAPT haplotype frequency between pathologically confirmed PD patients (n = 71) and controls (n = 52). We analyzed Braak LB stage, Braak neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) stage, and CERAD amyloid score by haplotype. We further tested the association between MAPT haplotype and semi-quantitative counts of LBs, NFTs, and neuritic plaques (NPs) in multiple neocortical regions. Consistent with previous reports, PD cases had an increased likelihood of carrying an H1/H1 genotype compared to controls (OR = 5.72, 95 % CI 1.80–18.21, p = 0.003). Braak LB, Braak NFT and CERAD scores did not differ by haplotype. However, H1/H1 carriers had higher LB counts in parietal cortex (p = 0.02) and in overall neocortical LBs (p = 0.03) compared to non-H1/H1 cases. Our analyses suggest that PD patients homozygous for the H1 haplotype have a higher burden of neocortical LB pathology.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Neuropathology, Lewy body, Tau, MAPT haplotype

Introduction

The pathogenesis of Parkinson disease (PD) remains poorly understood; however, the importance of genetic risk factors has been increasingly recognized. Genomic variation in the microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) has been shown by multiple genome-wide association studies to be associated with an increased risk of PD (Bekris et al. 2010). Specifically, PD patients are more likely than controls to carry the H1 haplotype (Desikan et al. 2015; Pankratz et al. 2012; Satake et al. 2009; Simon-Sanchez et al. 2009). The H1 and H2 haplotypes denote the two orientations of a large inversion that spans the MAPT gene locus. The H1 haplotype has been linked to increased risk of tauopathies such as progressive supranuclear palsy and primary age-related tauopathy (Baker et al. 1999; Crary et al. 2014; Santa-Maria et al. 2012). However, the link between the MAPT gene and PD risk is somewhat unexpected, since PD is characterized pathologically, not by tau aggregates, but by alpha-synuclein deposition in the form of Lewy bodies (LBs) and neurites.

Several lines of evidence suggest that tau can enhance alpha-synuclein aggregation in vitro and in vivo (Arima et al. 1999; Badiola et al. 2011; Clinton et al. 2010; Compta et al. 2011; Ishizawa et al. 2003). However, the effect of MAPT haplotype on LB formation in human disease is unclear. One group reported a trend towards increased neocortical LB burden in those carrying an H1 haplotype (Wider et al. 2012), but their analysis combined all cases of Alzheimer disease, Lewy body disorders, and vascular neuropathology, providing no clinical PD subgroup. Another smaller study found an increase in LB deposition across all brain regions in Lewy body dementia cases carrying an H1 haplotype (Colom-Cadena et al. 2013). However, this is of unclear significance, since Lewy body dementia has not been shown to be associated with the H1 haplotype (Seto-Salvia et al. 2011). In the current study, our goal was to assess the effect of MAPT haplotype on LB burden in autopsy-confirmed PD patients.

Methods

Subjects

Human brain samples were obtained from the New York Brain Bank at Columbia University. Cases were included in our analysis if they met the following criteria: clinical diagnosis of PD at time of death; Braak LB score ≥3 on neuropathological assessment; tissue available for MAPT haplotype analysis. For cases with available information, we collected disease duration (defined as age at death—age at disease onset; N = 18 H1/H1, 6 H2) and presence of memory impairment (assessed by score >0 on item 1 of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS); N = 13 H1/H1, 5 H2). For the H1/H1 cases, there were 35 Caucasian, 1 African-American, 2 Asian, and 13 without information. For H2 cases, there were 7 Caucasians and 13 without information. A group of elderly controls with minimal neuropathological abnormalities was previously described (Santa-Maria et al. 2012). They were derived from 7 centers: New York Brain Bank (1 subject), University of California San Diego (San Diego, CA, USA), the University of Kentucky (Lexington, KY, USA), the Banner Sun Health Research Institute (Sun City, AZ, USA), Northwestern University (Chicago, IL, USA), the University of Washington (Seattle, WA, USA), and Washington University (St Louis, MO, USA). All controls were of Caucasian ancestry, clinically non-demented, and had Braak NFT score 0–II and CERAD score 0–A. Another control group from the Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC), as described in (Allen et al. 2014), consisted of clinically non-demented subjects of European-American ancestry.

Genetics

DNA from cases was evaluated for MAPT haplotype by analyzing a haplotype-tagging single-nucleotide polymorphism (rs62063857) using the Sequenom MassArray iPlex method as previously described (Clark et al. 2014). For the ADGC controls, MAPT haplotype was inferred from another haplotype-tagging SNP, rs8070723 (Allen et al. 2014).

Neuropathology

Neuropathological analysis was performed as previously described (Vonsattel et al. 1995). The distribution of LB pathology was assessed according to the Braak LB staging system (Braak et al. 2003). The distribution of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) was designated according to the Braak NFT staging system (Braak and Braak 1995). CERAD criteria were used to evaluate the density of neuritic plaques (NP) (Mirra et al. 1991). Counts of neuropathological aggregates in specific brain regions were assessed semi-quantitatively by counting their maximal number in a 100× high power field (HPF). LBs were scored as follows: 0 for no LBs present; 1 for 1–2 LBs per HPF; 2 for 3–5 LBs per HPF; 3 for greater than 5 LBs per HPF. The neocortical regions analyzed for LBs were cingulate gyrus [Brodmann area (BA) 24], frontal cortex (BA9, BA4), temporal cortex (BA27, BA28, BA 36, BA20), parietal cortex (BA1, BA2, BA5, BA7), and occipitotemporal cortex (BA31, BA18, BA17). In addition, the scores for all 5 neocortical regions were added together to give a total neocortical LB score (possible scores 0–15), similar to the approach taken in (Colom-Cadena et al. 2013). For uniformity, in this analysis, we excluded 13 cases that had only been assessed with markers of Lewy body pathology other than alpha-synuclein (e.g., ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and/or modified Bielschowsky silver). Similar analyses were performed for regional counts of other aggregates, and categorized as follows: for NFTs, 0 for no NFTs present, 1 for 1–2 NFTs per HPF, 2 for 3–6 NFTs per HPF, 3 for 7–15 NFTs per HPF, 4 for greater than 15 NFTs per HPF; for NPs, 0 for no NPs present, 1 for 1–5 NPs per HPF, 2 for 6–10 NPs per HPF, 3 for 11–20 NPs per HPF, 4 for greater than 20 NPs per HPF. The neocortical regions analyzed for NFT and NP counts were the same as for LB analysis, except that precentral gyrus (BA4) was analyzed instead of cingulate cortex. Total neocortical NFT and NP scores were also calculated in a manner analogous to the total neocortical LB score. Analyses were performed by an experienced neuropathologist (JPV) blinded to MAPT genotype.

Statistical analysis

The association between PD status and MAPT haplotype, using either a dominant model (H1/H1 vs H2 carriers) or an allele model, was tested using either Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test (depending on sample size). In addition, for the PD group and elderly neuropathologic controls, a logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association between PD status (the outcome) and MAPT genotype (grouped as H1/H1 vs H2 carriers), adjusting for age at death and gender (the predictors). Among PD cases, the frequency of Braak LB stage, Braak NFT stage, CERAD score was compared between H1/H1 and H2 carriers, using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Similar analyses were performed on regional neocortical LB, NFT, and NP counts to identify an association with MAPT genotype. As these analyses were exploratory in nature, no correction for multiple comparisons was made. p values of 0.05 or lower were considered statistically significant for all analyses. The statistical software package used was SPSS, version 16.

Results

Seventy-one cases met the inclusion criteria for analysis: neuropathologically confirmed, clinical Parkinson disease, with tissue available for haplotype analysis. In these cases, 51 (72 %) were H1/H1 homozygotes, 19 (27 %) were H1/ H2 heterozygotes, and only one patient (1 %) was an H2/H2 homozygote (Table 1). There were no differences in gender, age at death, or disease duration between groups (Table 1). For cases with available information (13 H1/H1, 5 H2), all but one (an H1/H2 heterozygote) reported memory impairment by the time of death.

Table 1.

Association between MAPT haplotype, demographic factors, and pathological measures in PD patients

| Genotype | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| H1/H1 | H2 | ||

| N= | 51 | 20 | |

| Male, N (%) | 37 (73) | 16 (80) | 0.76 |

| Age at death, mean (SD) | 76 (7) | 77 (8) | 0.87 |

| Disease durationa, years, mean (SD) | 18.4 (8.4) | 15.8 (9.7) | 0.54 |

| Braak LB stage | 0.10 | ||

| 4 | 7 (14 %) | 6 (30 %) | |

| 5 | 17 (33 %) | 7 (35 %) | |

| 6 | 27 (53 %) | 7 (35 %) | |

| CERAD scoreb | 0.39 | ||

| 0 | 22 (44 %) | 5 (26 %) | |

| A | 16 (32 %) | 8 (42 %) | |

| B | 5 (10 %) | 6 (32 %) | |

| C | 7 (14 %) | 0 | |

| Braak NFT stageb | 0.52 | ||

| 0 | 7 (14 %) | 0 | |

| I–II | 8 (16 %) | 3 (16 %) | |

| III–IV | 20 (40 %) | 12 (63 %) | |

| V–VI | 15 (30 %) | 4 (21 %) | |

Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare Braak LB stage, Braak NFT stage, and CERAD score between H1/H1 and H2 carriers. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the gender, and a t test was used to compare age at death and disease duration

LB Lewy body, CERAD consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s Disease, NFT neurofibrillary tangle

For disease duration, data were available for 18 H1/H1 and 6 H2 cases

For CERAD and NFT scores, 50 H1/H1 and 19 H2 cases were assessed

As our center has an insufficient number of brains lacking pathology to serve as an unaffected comparison group, we compared the distribution of MAPT haplotypes in this PD group with that of a previously characterized (Santa-Maria et al. 2012) cohort of elderly controls with minimal neuropathological abnormalities (Supplementary Table 1). Since the control group was significantly older and more likely to be female, we performed a logistic regression analysis with PD status as the outcome, and MAPT genotype (categorized as H1/H1 vs H2 carrier, i.e., H1/H2 and H2/H2 genotypes), age at death and gender as predictors (Supplementary Table 1). Even taking age and gender into account, the H1/H1 genotype was associated with significantly higher risk of developing PD (OR = 5.72, 95 % CI 1.80–18.21, p = 0.003). We also compared the MAPT haplotype frequencies in our PD cohort to control subjects from the Alzheimer’s Disease Gene Consortium (ADGC; Supplementary Table 1). We found odds ratio comparable to those observed in prior studies (Pankratz et al. 2012), but these did not reach statistical significance in our relatively small cohort.

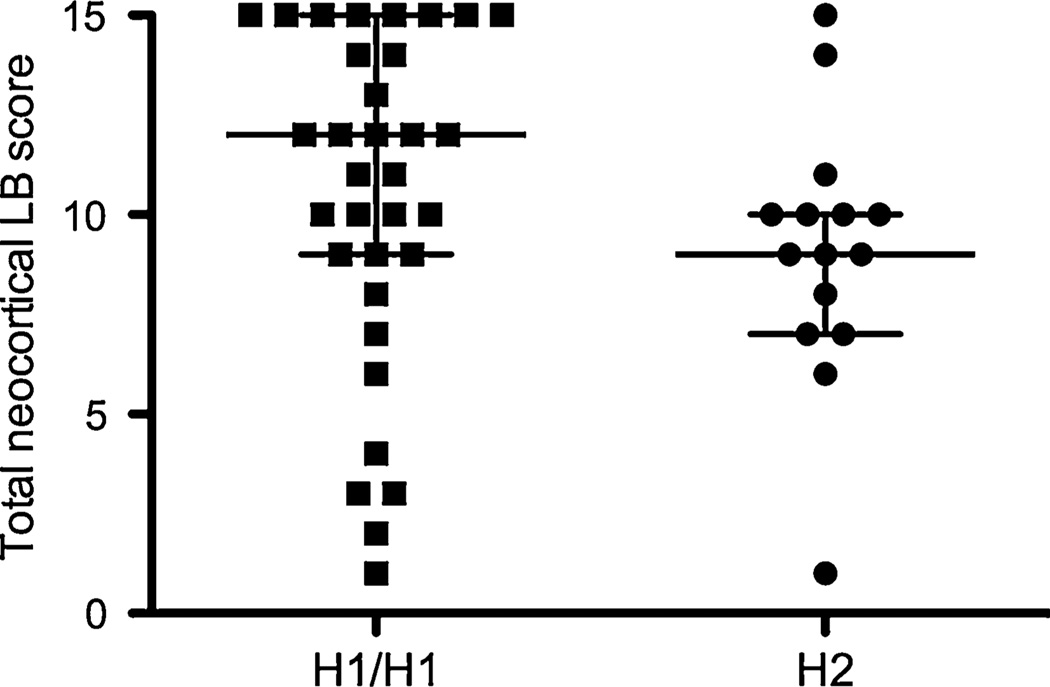

To explore the relationship between MAPT haplotype and LB deposition in PD, we compared the Braak LB score between those with H1/H1 genotype vs H2 carriers (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between the H1/H1 and H2 cases (p = 0.10). However, Braak LB staging describes the anatomic spread of LBs, not the severity of LB deposition. To more directly assess LB burden, we compared semi-quantitative LB counts in multiple neocortical regions (Table 2). We observed a significant association between higher LB counts and H1/H1 genotype in the parietal cortex (p = 0.02 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test). In addition, the total neocortical LB score (the sum of scores from each neocortical region) was higher in H1/H1 patients compared to H2 carriers (Table 2 and Fig. 1; p = 0.03 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test). These data suggest that PD patients with H1/H1 genotype may carry a greater burden of neocortical LBs.

Table 2.

Regional LB counts in H1/H1 and H2 PD patients

| LB count | Genotype | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1/H1 N (%) |

H2 N (%) |

||

| Frontal cortex | 0.38 | ||

| 0 | 7 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| 1–2 | 10 (24) | 8 (50) | |

| 3–5 | 9 (21) | 4 (25) | |

| ≥6 | 16 (38) | 3 (19) | |

| Parietal cortex | 0.02 | ||

| 0 | 7 (17) | 4 (25) | |

| 1–2 | 11 (27) | 9 (56) | |

| 3–5 | 6 (15) | 2 (13) | |

| ≥6 | 17 (41) | 1 (6) | |

| Temporal cortex | 0.08 | ||

| 0 | 3 (7) | 2 (13) | |

| 1–2 | 4 (10) | 2 (13) | |

| 3–5 | 4 (10) | 5 (31) | |

| ≥6 | 30 (73) | 7 (43) | |

| Cingulate cortex | 0.12 | ||

| 0 | – | – | |

| 1–2 | 6 (15) | 1 (6) | |

| 3–5 | 5 (12) | 8 (50) | |

| ≥6 | 30 (73) | 7 (44) | |

| Occipitotemporal cortex | 0.10 | ||

| 0 | 6 (15) | 2 (13) | |

| 1–2 | 2 (5) | 1 (7) | |

| 3–5 | 3 (8) | 6 (40) | |

| ≥6 | 28 (72) | 6 (40) | |

| Total LB score | 0.03 | ||

| Median (25, 75 %) | 12 (9, 15) | 9 (7, 10) | |

LB counts are categorized according to the maximum number of LBs seen per X100 field

The sum of column numbers for each region may vary due to unavailability of tissue in some cases

Fig. 1.

Total neocortical LB score in H1/H1 vs H2 PD patients. Total neocortical LB score for each patient is plotted. Lines represent median and interquartile range

We also assessed the relationship between MAPT haplotype and neurofibrillary tangles or neuritic plaques. Overall, there was no significant difference between H1/H1 and H2 cases in terms of NFT Braak stage or CERAD score (Table 1). We also performed a semi-quantitative analysis of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in multiple neocortical regions and found no difference in either measure between H1/H1 and H2 cases (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

Our study is consistent with an association between MAPT haplotype and neocortical LB deposition in a cohort of neuropathologically confirmed PD cases. Specifically, our data suggest that H1/H1 haplotype carriers had higher LB burden in the parietal cortex compared with H2 carriers. The link between H1/H1 genotype and LB deposition may be present in other neocortical regions as well, but our study did not have sufficient power to demonstrate these associations. This notion is supported by our finding that the total neocortical LB score was higher in H1/H1 patients compared to H2 carriers. Similar findings have been reported in prior studies of other populations with alpha-synuclein pathology (Colom-Cadena et al. 2013; Wider et al. 2012). These studies focused on patients with dementia, primarily AD or DLB. However, the H1 haplotype has not been consistently associated with either AD or DLB; in contrast, the risk of PD is clearly increased by the H1 haplotype. Our cohort of PD patients was more likely than controls to carry the H1/H1 genotype. The robustness of this association (relative to prior studies) may be due to our use of pathologically well-characterized patients and controls, as most prior studies did not utilize pathologically proven PD cases or elderly controls lacking any evidence of neurodegeneration neuropathologically. Consistent with this, comparison with a large, clinically defined control group from the ADGC yielded a more modest odds ratio, similar to that seen in prior studies (Pankratz et al. 2012). The current findings in our cohort of PD patients are therefore an important addition to the increasing evidence supporting a role for the tau gene in the pathophysiology of PD. Specifically, multiple studies suggest an interaction between tau and alpha-synuclein; molecular studies have demonstrated that tau enhances alpha-synuclein aggregation (Badiola et al. 2011); pathologic studies have found that tau is often a component of LBs (Arima et al. 1999; Ishizawa et al. 2003); and clinical studies describe a more severe phenotype in brains with concomitant tau and alphasynuclein pathology (Clinton et al. 2010; Compta et al. 2011),

The strengths of our study include our focus on pathologically confirmed PD patients, and semi-quantitative evaluation of multiple cortical regions. However, our study has several limitations. Most importantly, our study was exploratory in nature, with no correction for multiple comparisons in our statistical analyses (if such correction was employed, the differences in LB counts in parietal cortex and total neocortical LBs would not have reached statistical significance). A larger sample size would have increased the power of the study; ideally, our findings should be confirmed in an independent cohort. Another limitation of this study is that clinical diagnoses were based on a non-standardized clinical impression, rather than established diagnostic guidelines. However, all included cases met pathologic criteria for PD. The absence of a matched control population for comparison of haplotype frequency with our PD group, a result of our brain bank population, was another limitation. In particular, ethnicity has a significant impact on MAPT haplotype frequency. However, the main purpose of this study was to explore the effect of MAPT haplotype on PD pathology, rather than the risk of developing of PD, as the latter has been evaluated several times. The lack of a matched control group had no effect on the comparison of LB burden among PD cases. Finally, incomplete data for many of our cases prevented more detailed analysis of clinical characteristics.

The pathogenic effect of the H1 haplotype on tau function remains unclear. There are no differences in the coding region of brain-expressed exons between H1 and H2 haplotypes, implying that changes in gene regulation play an important role. A likely mechanism is alternative splicing of the tau gene. Inclusion of exon 10 leads to the production of 4R tau, which is more prone to aggregate. H1-encoded tau mRNA is more likely to contain exon 10 compared to H2-encoded transcripts (Caffrey et al. 2006; Majounie et al. 2013). Another alternative splicing event, inclusion of exon 3, inhibits tau aggregation, and H1-derived transcripts are less likely to contain exon 3 (Caffrey et al. 2008; Trabzuni et al. 2012). However, the significance of these splicing changes in primary synucleinopathies, such as PD, is unclear.

Several studies have found that the H1 haplotype correlates with increased risk of dementia in PD (Goris et al. 2007; Seto-Salvia et al. 2011; Williams-Gray et al. 2009), although this is not a universal finding (Irwin et al. 2012). In our cohort, the number of cases with data regarding memory impairment was small, and nearly all reported memory difficulties. Our observation of increased cortical LB deposition in H1/H1 patients may represent a neuropathological substrate underlying the likely increased risk of dementia. Indeed, other studies have found that cortical LB burden can be a predictor of dementia in PD (Horvath et al. 2013; Irwin et al. 2012), or have shown that even in healthy H1 carriers, H1 is associated with reduced cognitive function (Winder-Rhodes et al. 2015). Interestingly, H1 haplotype was found to be more common in patients with atremulous PD, a more clinically severe phenotype that portends a greater risk of dementia (Di Battista et al. 2014). Taken together, these findings imply that the H1 haplotype, in addition to increasing the risk of developing PD, may also modulate the expression of several clinical factors associated with poor prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Codruta Chiuzan and Jimmy Duong for assistance with statistical analysis. This project was funded by the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation (LNC, Lucien Cote Early Investigator Award to OAL), a Pilot Research Award (CAMPR-BASIC to JFC, OAL) and use of Biostatistics Core Resource from the Columbia University Irving Institute (NIH UL1-TR00040), and by the NINDS (K08-NS070608 for OAL, P50NS038370 for LNC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- CERAD

Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s Disease

- LB

Lewy body

- MAPT

Microtubule-associated protein tau

- NFT

Neurofibrillary tangle

- PD

Parkinson disease

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00702-016-1552-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest and no competing financial interests.

References

- Allen M, et al. Association of MAPT haplotypes with Alzheimer’s disease risk and MAPT brain gene expression levels. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6:39. doi: 10.1186/alzrt268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arima K, et al. Cellular co-localization of phosphorylated tau- and NACP/alpha-synuclein-epitopes in Lewy bodies in sporadic Parkinson’s disease and in dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Res. 1999;843:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01848-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badiola N, et al. Tau enhances alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity in cellular models of synucleinopathy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, et al. Association of an extended haplotype in the tau gene with progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:711–715. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekris LM, Mata IF, Zabetian CP. The genetics of Parkinson disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2010;23:228–242. doi: 10.1177/0891988710383572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00021-6. (discussion 278–284) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey TM, Joachim C, Paracchini S, Esiri MM, Wade-Martins R. Haplotype-specific expression of exon 10 at the human MAPT locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3529–3537. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey TM, Joachim C, Wade-Martins R. Haplotype-specific expression of the N-terminal exons 2 and 3 at the human MAPT locus. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1923–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LN, Liu X, Parmalee NL, Hernandez N, Louis ED. The microtubule associated protein tau H1 haplotype and risk of essential tremor. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:1044–1048. doi: 10.1111/ene.12335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton LK, Blurton-Jones M, Myczek K, Trojanowski JQ, LaFerla FM. Synergistic Interactions between Abeta, tau, and alpha-synuclein: acceleration of neuropathology and cognitive decline. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7281–7289. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0490-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom-Cadena M, et al. MAPT H1 haplotype is associated with enhanced alpha-synuclein deposition in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compta Y, et al. Lewy- and Alzheimer-type pathologies in Parkinson’s disease dementia: which is more important? Brain. 2011;134:1493–1505. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crary JF, et al. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:755–766. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1349-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, et al. Genetic overlap between Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease at the MAPT locus. Mol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Battista ME, et al. Clinical subtypes in Parkinson’s disease: the impact of MAPT haplotypes. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2014;121:353–356. doi: 10.1007/s00702-013-1117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris A, et al. Tau and alpha-synuclein in susceptibility to dementia in, Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:145–153. doi: 10.1002/ana.21192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath J, Herrmann FR, Burkhard PR, Bouras C, Kovari E. Neuropathology of dementia in a large cohort of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Park relat disord. 2013;19:864–868. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DJ, et al. Neuropathologic substrates of Parkinson disease dementia. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:587–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.23659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa T, Mattila P, Davies P, Wang D, Dickson DW. Colocalization of tau and alpha-synuclein epitopes in Lewy bodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:389–397. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majounie E, et al. Variation in tau isoform expression in different brain regions and disease states. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1922.e7–1922.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratz N, et al. Meta-analysis of Parkinson’s disease: identification of a novel locus, RIT2. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:370–384. doi: 10.1002/ana.22687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa-Maria I, et al. The MAPT H1 haplotype is associated with tangle-predominant dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:693–704. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1017-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake W, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants at four loci as genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/ng.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto-Salvia N, et al. Dementia risk in Parkinson disease: disentangling the role of MAPT haplotypes. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:359–364. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Sanchez J, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabzuni D, et al. MAPT expression and splicing is differentially regulated by brain region: relation to genotype and implication for tauopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4094–4103. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonsattel JP, et al. An improved approach to prepare human brains for research. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:42–56. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wider C, et al. An evaluation of the impact of MAPT, SNCA and APOE on the burden of Alzheimer’s and Lewy body pathology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:424–429. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Gray CH, et al. The distinct cognitive syndromes of Parkinson’s disease: 5 year follow-up of the CamPaIGN cohort. Brain. 2009;132:2958–2969. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder-Rhodes SE, Hampshire A, Rowe JB, Peelle JE, Robbins TW, Owen AM, Barker RA. Association between MAPT haplotype and memory function in patients with Parkinson’s disease and healthy aging individuals. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1519–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.