Abstract

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic inflammatory liver disease of unknown etiology, primarily targeting cholangiocytes at any portion of the biliary tree. No effective medical treatments are currently available. A unique feature of PSC is its close association (about 80%) with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mainly ulcerative colitis (UC). As in many chronic inflammatory conditions, cancer development can complicate PSC, accounting for >40% of deaths. Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) and colorectal carcinoma (CRC) have been variably associated to PSC, with a prevalence up to 13–14%. The risk of cancer is one of the most challenging issues in the management of PSC; it raises several questions about cancer surveillance, early diagnosis, prevention and treatment.

Key Messages

Among the different cancers complicating PSC, CCA is the most relevant, because it is more frequent (incidence of 0.5–1.5%) and because the prognosis is poor (5-year survival <10%). Early diagnosis of CCA in PSC can be difficult because lesions may not be evident in radiological studies. Surgical resection provides disappointing results; liver transplantation combined with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is being proposed, but this approach is limited to a highly selected group of patients and is available only in a few specialized centers. Similar to CCA, GBC carries a dismal prognosis. Since it is difficult to discriminate GBC from other gallbladder abnormalities, cholecystectomy has been proposed in all gallbladder lesions detected in PSC, regardless of their size. CRC is a frequent complication of PSC associated to UC; its incidence steadily increases with time of colitis, reaching up to 20–30% of the patients after 20 years. Colonoscopy with extensive histologic sampling at an annual/biannual interval is an effective surveillance strategy. However, when dysplastic lesions are detected, preemptive proctocolectomy should be considered.

Conclusions

PSC may be regarded as paradigmatic of the sequence leading from chronic inflammatory epithelial damage to neoplastic transformation. Understanding the molecular mechanisms regulating this patho-genetic sequence, may improve strategies of disease surveillance and cancer prevention and treatment. PSC is a chronic inflammatory cholangiopathy of unknown etiology but likely immune-mediated, characterized by peribiliary inflammation and fibrosis leading to strictures in any portion (intra-and/or extrahepatic) of the bile duct system. No effective medical treatments are currently available. A unique feature of PSC is the close association (about 80%) with IBD, mainly UC, often diagnosed before PSC (PSC/UC). As in other chronic inflammatory diseases, development of malignancies is a feared complication of PSC.

Keywords: Cholangiocyte, Cholangiocarcinoma, Colorectal cancer, Gallbladder carcinoma, Ulcerative colitis

Previous studies showed that more than 40% of deaths in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) patients were related to cancer [1]. Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) and colorectal carcinoma (CRC) in subjects with concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), have been variably reported, with a prevalence of up to 13–14% for hepatobiliary malignancies [2, 3]. Cancer development is one of the most challenging issues in the management of PSC, as it can occur at any time during the course of the disease and is generally unpredictable. Therefore, it raises a number of still unanswered questions about disease surveillance, its early diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Here, we will first discuss the clinical aspects of PSC and its main malignancies (CCA, GBC and CRC), and then we will briefly outline some novel findings on the molecular mechanisms underlying the close association of PSC with CCA and CRC, that may become relevant to clinical management.

PSC and Malignancies: CCA, GBC, CRC and Other Carcinomas

PSC and CCA

Among the different cancer types complicating PSC, CCA is the most relevant, in terms of epidemiological burden, with a lifetime risk of around 7–14% and prognosis with a 5-year survival <10% [2]. In sharp contrast with HCC development in liver cirrhosis, risk of CCA in PSC is not dependent upon the duration of the disease, as CCA may often develop within the first year from PSC diagnosis [2]. CCA arising in PSC affects younger subjects than CCA without PSC [4, 5] and specific risk factors, such as a long history of IBD [6] and an excessive alcohol intake [7], have been variably described, though not confirmed in other studies [8]. Noteworthy, CCA does not appear to complicate the ‘small duct’ PSC variant [9].

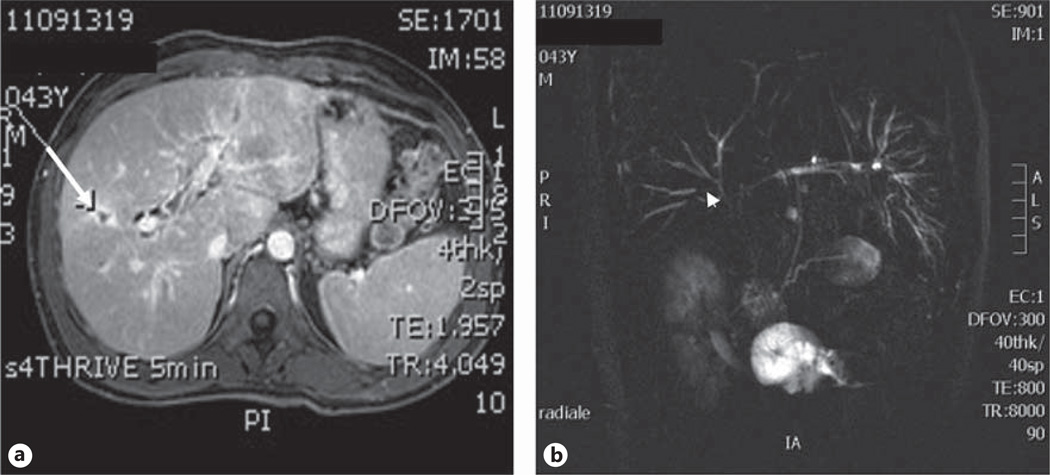

When managing a patient with CCA, regardless of the liver background, a major clinical problem is the late diagnosis, since CCA is often diagnosed at a stage precluding curative surgical approaches. The presence of PSC is a further challenging issue because the disease can either mimic or hide CCA. Thus, in the setting of PSC, early diagnosis of CCA is even more difficult, especially in the case of dominant strictures in which neoplastic and benign lesions are morphologically similar at radiological studies (fig. 1). In a large series of PSC patients undergoing surgery for presumed CCA, a benign disease was diagnosed in 24% [10]. On the other hand, in PSC patients undergoing liver transplantation, CCA was not recognized until laparotomy in up to 27% of cases [6]. Moreover, the phenotype of CCA associated to PSC is more commonly the infiltrating desmoplastic ductal type rather than the intrahepatic mass-forming focal lesion [5], thus making its recognition more difficult by cross-sectional imaging studies [11]. PSC-associated CCA localized to the extrahepatic portion of the biliary tree are uncommon (<10%) [11].

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance images showing the morphologic features suggestive of malignancy in PSC. a Axial T1-weighted image showing ductal dilatation with peri-ductal gadolinium contrast-enhancement (arrow). b Coronal MRCP image showing a dominant stricture localized at the peri-hilar region (arrowhead).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) coupled with magnetic resonance cholangiography is generally considered the first-line investigation for the detection of CCA [12], while ultrasound (US) examination seems to have better accuracy in discriminating CCA from underlying PSC [13]. Therefore, diagnosis of CCA in PSC often requires a combination of imaging studies performed when clinical deterioration (worsening of jaundice, weight loss and abdominal pain) suddenly develops, even though at this stage the disease may be advanced [5, 13].

To improve PSC surveillance and early diagnosis of CCA, assessment of serological biomarkers has been widely proposed. Among them, the most extensively studied is CA19–9. In a study on 208 patients with PSC, CA19–9 serum levels were generally higher in patients with CCA than in patients without CCA, and a cut-off level of 129 U/ml was identified [14]. However, a recent study showed that PSC-related CCA had lower CA19–9 levels than CCA without PSC (median 51 vs. 150 U/ml) [5]. Moreover, significant, though transient, increases in CA19–9 serum levels may frequently occur during acute biliary infections not rarely complicating PSC, and up to 37% of PSC patients with CA19–9 levels higher than 129 U/ml do not have CCA [15]. Recent data showed that allelic variants of fucosyltransferases 2 and 3 (FUT2/3), enzymes critically involved in surface glycoprotein synthesis, could also influence serum levels of CA19–9 [16]. Furthermore, 7–10% of the general population do not express CA19–9 and cannot take advantage of this test [17].

Conventional cytology of biliary brushing obtained with ERCP is extremely specific for CCA diagnosis (97%), but its sensitivity is quite low – around 43% [18]. In fact, the strong desmoplastic reaction typically featuring PSC-associated CCA may lead to unsuitable cytological specimens. Moreover, recurrent acute cholangitis may increase the likelihood of false positive results [19]. Therefore, new procedures such as digital image analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) have been investigated to increase CCA detectability in cases of negative conventional cytology [20]. In particular, FISH is helpful because it may identify chromosomal abnormalities associated with a higher risk of CCA, such as aneuploidy and polisomy [21]. When polisomy is detected, surgical approach for CCA is recommended [22]. However, FISH sensitivity and specificity are still far away from providing an accurate prediction of CCA (about 70%) [20]. Furthermore, these tests cannot be routinely performed in a large scale, because of their high costs, and the small subsets of patients, who can potentially benefit from them. Overall, these data highlight the concept that there is an urgent need to identify new strategies to improve the early detection of CCA in PSC. 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computerized tomography scan is a promising tool for discriminating CCA from benign lesions in patients with dominant strictures: a high tissue uptake index (SUVmax/liver ≥ 3.3) is able to identify CCA with high sensitivity and specificity (both around 90%), while an index <2.4 excludes CCA [23]. However, a potential limitation of its diagnostic abilities in early PSC-associated CCA is the occurrence of false positivity in areas with ongoing inflammation.

The current uncertainty in the diagnostic abilities of CCA in PSC makes the choice of the best treatment approach quite difficult. Results with surgical resection have been disappointing in terms of postoperative morbidity and mortality (with a 5-year survival rate <30% including cases with negative resection margins), even when liver function is preserved and portal hypertension has not developed yet [24]. Therefore, liver transplantation (LT) preceded by neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is currently considered the best approach for CCA in PSC when localized to the hepatic parenchyma or to the hilum. LT seems to be much more effective than surgical resection in PSC patients, with a 5-year survival of up to 80% (table 1) [25]. Although performed only in selected cases, these results are very similar to those reported for LT in HCC [26]. Unfortunately, LT is available only for a small subgroup of patients and in highly specialized centers. Some authors have suggested prophylactic LT for patients with PSC, but as most of them will not develop CCA, preemptive LT is ethically not justified, at least in geographic areas with shortage of donors. Because the sequence inflammation-metaplasia-dysplasia-cancer leads to CCA in PSC [27, 28], LT has been proposed for patients with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) in brush cytology [28]. Notably, HGD may involve multiple segments of the biliary tree and associate with CCA in liver parenchyma. However, dysplasia detection on brush cytology is not a rare finding in PSC, especially in patients with advanced disease, and it can regress with resolution of acute infection; therefore, its management remains controversial. According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver Guidelines, LT may be considered a reasonable option in patients with HGD [29], but stronger evidences are needed to better support this approach in clinical practice.

Table 1.

Comparison of patient survival and tumor recurrence after resection or LT with neoadjuvant therapy in PSC-associated CCA

| Patients, n | Survival, % |

Tumor recurrence, % |

Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | ||||

| Resection | 7 | 30 | NA | NA | NA | [41] |

| 26* | 82 | 48 | 21 | 27 | [24] | |

| LT with neoadjuvant therapy | 38 | 90 | 83 | 79 | 19.6** | [42] |

| 42 | 91 | 80 | 76 | 17 | [25] | |

| 22 | 92 | 82 | 82 | 13 | [24] | |

NA = Not assessed.

Only 2 patients with PSC were included in this study.

CCA without PSC was also included in recurrence assessment.

Currently, there are no well-validated surveillance protocols for CCA in PSC patients because of the lack of longitudinal studies proving the benefit of cost-effectiveness of screening strategies [30]. Therefore, the concept that the current approaches of screening may be actually effective in prolonging patient survival is a matter of debate [31]. Despite these limitations, noninvasive imaging studies, usually MRI with MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), complemented by serological CA19–9 assessment at annual intervals may be recommended [7, 22]. In particular, careful surveillance is pivotal in PSC patients listed for LT for end-stage disease, since detecting CCA can drastically modify the therapeutic approach. Most centers are now applying integrated strategies, usually CA19–9 serum levels and MRI/MRCP or ERCP with brushing cytology combined to MRI [32]. In the next few years, 18F-FDG positron emission tomography might provide an additional and important tool for the pre-transplant screening, given its superiority to conventional radiology in the early detection of CCA [33].

PSC and GBC

Gallbladder abnormalities are a frequent finding in PSC, observed in about 40% of cases. Among them, risk of GBC deserves specific attention. Although most of the gallbladder lesions are benign, including stones, in a large study performed in 286 PSC patients, the overall prevalence of gallbladder mass lesions was 6%, with more than a half resulting to be malignant [34]. Conversely, GBC were <10% of all gallbladder lesions in non-PSC patients [35]. In PSC-associated GBC, no significant association with gender, bacterial cholangitis and biliary cirrhosis was found [34]. As for CCA complicating PSC, even for GBC, dysplasia may be regarded as a pre-malignant lesion promoted by chronic inflammatory changes. Indeed, in a study on 72 resected gallbladders from PSC patients, 14% harbored adenocarcinoma and among them, focal areas with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and HGD were found in 100% of cases, while intestinal metaplasia was present in 90% [36].

Similarly to CCA, PSC-associated GBC tends to affect younger individuals (<60 years) than GBC not associated to PSC, and it carries a dismal prognosis. For these reasons, careful surveillance with an annual US examination is recommended [30]. Unfortunately, US findings are not accurate enough to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions: discrepancies between pre-operative US and histological analysis after cholecystectomy were reported in 63% of cases [37]. Therefore, diagnostic performance of other US-based examinations, such as endoscopy US and contrast enhanced US have been evaluated in GBC. In particular, endoscopy US is useful to discriminate polyps from cholesterol deposits along the gallbladder wall, given its strong ability in identifying aggregated echogenic spots; however, it must be underlined that gallbladder lesions without a similar pattern do not necessarily relate to malignancy [38, 39]. Indications for cholecystectomy are still hotly debated: although cholecystectomy is currently recommended in all gallbladder lesions detected in PSC, regardless of their size, it is important to note that very few worrisome gallbladder lesions diagnosed as adenocarcinoma, <1 cm have been described so far in PSC patients [40]. Moreover, given the high surgical risk of PSC patients, and the unlikelihood of polyps >1 cm to be malignant, a more prudent strategy with systematic surveillance of lesions <0.8 cm could be reasonable when liver function is impaired [22].

PSC and CRC

PSC is associated with IBD in approximately 70% of patients, with some variability among geographical areas [43]. This association is more strict for ulcerative colitis (UC) (8% of UC subjects have concurrent PSC) than for Crohn’s disease (CD) (1–3%) [44, 45]. Early studies showed that patients with UC and PSC (PSC/UC) had a 4-fold increased risk for colorectal dysplasia and carcinoma compared with patients with UC alone and a 10-fold higher risk than the general population [46]. The cumulative incidence of CRC in PSC/UC subjects steadily increases with time of colitis, from 8–10% after 10 years to 20–30% after 20 years, much higher than that reported in UC alone (2 and 5%, respectively). A similar time-dependent increase is described for colon dysplasia, being 15% after 10 years and 30% after 20 years [8, 47]. In PSC patients, CRC association is classically considered to be stronger with UC than with CD. However, a few recent studies have generated some controversy on this issue. In a retrospective study focusing on PSC association to colonic CD, including 35 patients with PSC with CD (PSC/CD) and 114 patients with CD without PSC, an increased risk of dysplasia or CRC was not found in PSC/CD [48]. However, the reduced number of patients with PSC/CD may explain the lack of association with CRC in this series. Surprisingly, a population-based Swedish study did not confirm PSC as an independent risk factor for CRC in IBD. In a cohort of 299 patients with PSC diagnosed from 1992 to 2005, PSC or PSC with concurrent IBD were not associated with a higher incidence of CRC and dysplasia compared with the general population. The lowered incidence of CRC in this cohort was partly explained as a result of a better management of IBD and, probably, of a more timely diagnosis of IBD in PSC [49]. A larger population-based Dutch study including 590 patients with PSC with a median follow-up of 7 years, on the other hand, showed a 10-fold increased risk of CRC in PSC/IBD (mainly UC) as compared to IBD alone. Interestingly, in PSC/IBD patients, CRC developed at a much younger age (39 years) than in IBD alone (59 years) [50].

A number of caveats have to be borne in mind to improve the detectability of CRC in PSC patients (table 2). The phenotype of IBD in PSC is characterized by a milder clinical course despite a higher incidence of pancolitis (>90%) than in IBD alone, and a more frequent involvement of the right hemicolon proximal to the splenic flexure [51, 52]. Furthermore, in PSC patients, IBD can have a minimal endoscopic activity in spite of relevant inflammatory changes at mucosal histology that may contribute to an increased risk of CRC. This is a crucial element, given the propensity of CRC arising in IBD to originate from flat and non-polypoid dysplastic lesions, and to be multifocal, likely reflecting diffuse pro-oncogenic effects of colonic mucosal inflammation. In addition, some specific manifestations of PSC, such as the development of dominant strictures, seem to correlate with an increased broad risk of malignancy, including CRC in patients with PSC/IBD [53] (table 2).

Table 2.

Peculiarities of PSC-associated IBD relevant for CRC detection

| Mild clinical course |

| High incidence of pancolitis |

| Frequent involvement of the right hemicolon |

| Minimal endoscopic activity in spite of relevant histological alterations |

| Flat and multifocal dysplastic lesions |

| Increased CRC risk associated with development of dominant stricture |

| Increased CRC risk associated with LT |

Taken together, all these observations support the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases surveillance recommendations to perform annual colonoscopy (rather than sigmoidoscopy) with systematic histological sampling throughout the colon, starting immediately with the initial diagnosis of PSC in subjects with known IBD, and a 5-year endoscopic follow-up in patients with PSC alone [30]. Moreover, careful cancer screening must be stringent in patients with PSC/IBD and dominant strictures [54]. Colonoscopy surveillance has been shown to be effective in improving outcome related to CRC mortality in PSC/IBD patients [50].

However, a critical issue of colonoscopy-based surveillance is that biopsies provide only limited information, because only a small tissue sample of the entire colon can be examined. An emerging alternative to improve detection abilities of CRC and dysplasia is the use of chromoendoscopy. Chromoendoscopy should be particularly useful in PSC/IBD patients with indefinite dysplasia or LGD, not yet eligible for colectomy, to identify flat lesions amenable to endoscopic mucosectomy, thereby avoiding the risk of surgery when liver function is compromised [52].

Notably, LT significantly increased the risk of developing CRC in patients with PSC/IBD, approximately by 10 times when compared with all patients undergoing LT and up to 20 times with respect to the general population [55, 56]. PSC/IBD patients have an increased risk of CRC after LT when compared with PSC/IBD without LT (OR 4.4). On the basis of these data, some authors propose preemptive proctocolectomy in PSC/UC patients before undergoing LT. However, 5-year survival of patients who underwent proctocolectomy before LT did not differ from the survival of PSC/UC patients transplanted with an intact colon (86% for both group) [22, 57]. Thus, although the risk of developing CRC is increased, this is not sufficient by itself to justify a preemptive proctocolectomy in PSC/UC patients who are candidate to LT.

Conversely, evidence of HGD and unresectable LGD in histologic specimens is a strong pointer to proctocolectomy. In fact, the risk of developing synchronous sites of dysplasia is higher in patients with PSC/IBD than in patients with IBD alone [58]. Therefore, as dysplasia might preclude adequate surveillance strategies, proctocolectomy should be recommended in PSC/UC patients with HGD and unresectable LGD [52]. However, since multifocal LGD showed a significant association with carcinoma progression in PSC/UC patients, proctocolectomy has been proposed even for this group of patients [59].

Whether drug treatments usually performed in PSC/IBD may exert some chemopreventive effects on CRC development is a controversial issue. A protective role of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has been suggested, although data are conflicting, with some studies showing variable benefit [60, 61] and other reporting no significant effects [62]. A recent meta-analysis on 8 studies evaluating 177 CRC in 763 patients with PSC/IBD, showed a significant protective effect of UDCA on the risk of developing both CRC and dysplasia (OR 0.35). By subgrouping, a stronger protective effect was found with UDCA at low doses (8–15 mg/kg/day; OR 0.19) [63]. In contrast, a nested cohort study demonstrated an increased risk of CRC and dysplasia (hazard ratio 4.4) associated with high doses of UDCA (28–30 mg/kg/day) compared with a placebo group [64]. Whereas American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends against the use of UDCA in all PSC patients, including PSC/IBD, European Association for the Study of the Liver recommends UDCA in high-risk groups as those with a strong family history of CRC, previous evidence of colorectal dysplasia or long lasting extensive colitis [29]. Similarly, mesalazine alone or in combination with UDCA, has been reported to play a chemoprophylactic role in PSC/UC [60]. However, a Swedish study performed in 143 patients with UC showed that in PSC/UC patients, the risk of CRC or dysplasia remains increased compared with UC without PSC, regardless of sulfasalazine treatment [65].

PSC and Other Malignancies

Incidence of HCC in PSC does not seem to be increased, irrespective of its progression to cirrhosis [66, 67]. In contrast, an increased risk for pancreatic cancer has been reported in PSC, though discrimination from extrahepatic CCA of the common bile duct, though rare in PSC, can be difficult [3].

Understanding the Mechanisms of Malignant Transformation in PSC: Clues from Epithelial-Mesenchymal Interactions

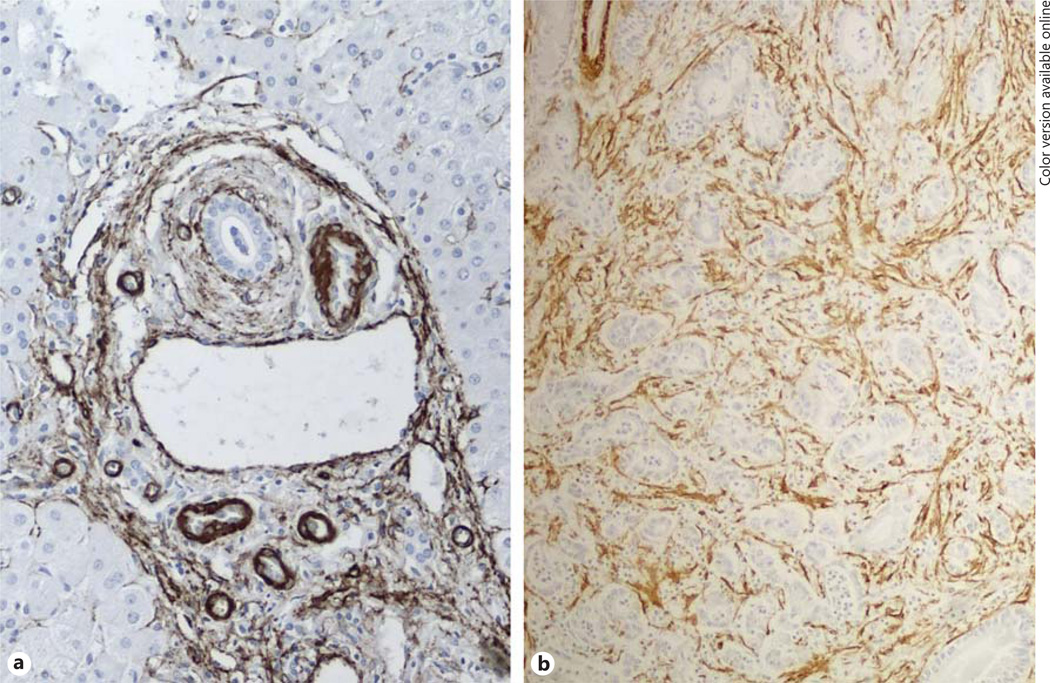

Although PSC may classically be regarded as a disease paradigmatic of the sequence of events leading from a chronic inflammatory epithelial damage to a neoplastic transformation, mechanisms regulating this progression are hitherto largely uncertain. The pathognomonic histological lesion of PSC, featuring a dense accumulation of fibroblasts with progressive matrix deposition closely around the bile duct, suggests that cell interactions between the epithelial and the mesenchymal compartments are strongly involved in these mechanisms (fig. 2). Local production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, mainly IL-6, nitric oxide (NO) and reactive nitrogen and oxygen species and consequent stimulation of proliferation with accumulation of DNA damage is likely the main pathogenetic event leading to the transformation of cholangiocytes [68]. Inducible NO synthase (iNOS or NOS2) is significantly upregulated in the biliary epithelium of patients with PSC, as a result of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, released within the inflammatory microenvironment [69]. Once transformed, neoplastic cholangiocyte gains in turn the ability to release a range of soluble mediators (growth factors, cytokines and chemokines), which induce a stromal reaction favoring fundamental pro-invasive functions of CCA. Recent data from our laboratory indicate platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-D as a critical mediator of tumor-stroma interactions in CCA. PDGF-D secreted by tumoral cholangiocytes stimulate recruitment of cancer-associated fibroblasts [70] and endow them with a range of secretory functions, including vascular endothelial growth factor-C, promoting lymphangiogenesis, a pivotal route of CCA invasiveness [71]. We have also preliminary evidence showing that NO donors stimulated PDGF-D secretion by cultured human cholangiocytes [Fabris L, Strazzabosco M, unpublished observations]. Overall, these data point toward a central role of PDGF-D, linking NO effects on malignant transformation with generation of a stromal reaction favoring the lymphatic spread.

Fig. 2.

Similar peribiliary localization of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA)+ myofibroblasts in PSC and CCA. a A dense stromal reaction with abundance of α-SMA+ myofibroblasts developing in close vicinity to bile ducts represents the classical histological lesion of PSC. b An abundant tumor reactive stroma, originally termed as desmoplasia, is also a defining feature of the CCA subtype most commonly arising in PSC. Immunoperoxidase for α-SMA, M = 200×.

As discussed earlier, an intriguing feature of PSC is that its pro-oncogenic effects may extend to the colon when associated to IBD. Bile acids might play a relevant role in the pathogenesis of CRC in PSC/UC, given their proliferative effects on intestinal epithelial cells; the protective effects on CRC development exerted by UDCA as shown by some studies may be a consequence of its effects on the bile acids pool [61, 72]. A recent study has proposed the tumor suppressor gene p53, which is frequently mutated in CCA, as putative player of the higher susceptibility of CRC in PSC/UC patients [73]. In this study, p53 was overexpressed in the intestinal mucosa of PSC/UC patients compared with UC without PSC, even in the absence of dysplasia, thus suggesting that PSC might play a direct oncogenic role in UC-associated colorectal carcinogenesis, regardless of the mucosal inflammatory activity. This study may be an example of how identification of pro-oncogenic signatures may be helpful in selecting patients with higher risk of malignancy, who may thus benefit from closer endoscopic follow-up or more radical approaches (i.e. LT or proctocolectomy).

Conclusions

PSC classically represents a disease model of the oncogenic effects exerted by chronic inflammation, which drives the progression of a persistent epithelial damage to malignant transformation. However, comprehension of the specific mechanisms regulating this pathogenetic sequence remains limited. Consequently, uncertainties on the strategies of disease surveillance and cancer prevention and treatment make difficult the clinical management of PSC. Understanding the molecular mechanisms at the basis of carcinogenesis in PSC might provide important clues for facing this ‘sword of Damocles’ pending throughout the course of the disease.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

Progetto di Ricerca Ateneo 2011 (grant #CPD113799/11) to L.F. NIH Grants DK079005 and DK034989 Silvio O. Conte Digestive Diseases Research Core Centers, grant from ‘PSC partners for a care’, projects CARIPLO 2011-0470 and PRIN 2009ARYX4T_005 to M.S.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Fevery J, Henckaerts L, Van Oirbeek R, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Nevens F, Van Steenbergen W. Malignancies and mortality in 200 patients with primary sclerosering cholangitis: a long-term single-centre study. Liver Int. 2012;32:214–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergquist A, Ekbom A, Olsson R, Kornfeldt D, Lööf L, Danielsson A, Hultcrantz R, Lindgren S, Prytz H, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Almer S, Granath F, Broomé U. Hepatic and extra-hepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2002;36:321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergquist A, Said K, Broomé U. Changes over a 20-year period in the clinical presentation of primary sclerosing cholangitis in Sweden. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:88–93. doi: 10.1080/00365520600787994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burak K, Angulo P, Pasha TM, Egan K, Petz J, Lindor KD. Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:523–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darwish Murad S, Kim WR, Therneau T, Gores GJ, Rosen CB, Martenson JA, Alberts SR, Heimbach JK. Predictors of pretransplant dropout and posttransplant recurrence in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:972–981. doi: 10.1002/hep.25629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boberg KM, Bergquist A, Mitchell S, Pares A, Rosina F, Broomé U, Chapman R, Fausa O, Egeland T, Rocca G, Schrumpf E. Cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis: risk factors and clinical presentation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1205–1211. doi: 10.1080/003655202760373434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalasani N, Baluyut A, Ismail A, Zaman A, Sood G, Ghalib R, McCashland TM, Reddy KR, Zervos X, Anbari MA, Hoen H. Cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a multicenter case-control study. Hepatology. 2000;31:7–11. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claessen MM, Vleggaar FP, Tytgat KM, Siersema PD, van Buuren HR. High lifetime risk of cancer in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2009;50:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angulo P, Maor-Kendler Y, Lindor KD. Small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis: a long-term follow-up study. Hepatology. 2002;35:1494–1500. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton RA, Clarke DL, Currie EJ, Madhavan KK, Parks RW, Garden OJ. Incidence of benign pathology in patients undergoing hepatic resection for suspected malignancy. Surgeon. 2003;1:32–38. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(03)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fevery J, Verslype C. An update on cholangiocarcinoma associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:236–245. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328337b311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno Luna LE, Gores GJ. Advances in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(11 suppl 2):S15–S19. doi: 10.1002/lt.20938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Enders FB, Halling KC, Lindor KD. Utility of serum tumor markers, imaging, and biliary cytology for detecting cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:1106–1117. doi: 10.1002/hep.22441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy C, Lymp J, Angulo P, Gores GJ, Larusso N, Lindor KD. The value of serum CA 19-9 in predicting cholangiocarcinomas in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1734–1740. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2927-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinakos E, Saenger AK, Keach J, Kim WR, Lindor KD. Many patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and increased serum levels of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 do not have cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:434–439.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wannhoff A, Hov JR, Folseraas T, Rupp C, Friedrich K, Anmarkrud JA, Weiss KH, Sauer P, Schirmacher P, Boberg KM, Stremmel W, Karlsen TH, Gotthardt DN. FUT2 and FUT3 genotype determines CA19–9 cut-off values for detection of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2013;59:1278–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nehls O, Gregor M, Klump B. Serum and bile markers for cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:139–154. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trikudanathan G, Navaneethan U, Njei B, Vargo JJ, Parsi MA. Diagnostic yield of bile duct brushings for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siqueira E, Schoen RE, Silverman W, Martin J, Rabinovitz M, Weissfeld JL, Abu-Elmaagd K, Madariaga JR, Slivka A. Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:40–47. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navaneethan U, Njei B, Venkatesh PG, Vargo JJ, Parsi MA. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:943–950.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barr Fritcher EG, Kipp BR, Voss JS, Clayton AC, Lindor KD, Halling KC, Gores GJ. Primary sclerosing cholangitis patients with serial polysomy fluorescence in situ hybridization results are at increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2023–2028. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1842–1852. doi: 10.1002/hep.24570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sangfelt P, Sundin A, Wanders A, Rasmussen I, Karlson BM, Bergquist A, Rorsman F. Monitoring dominant strictures in primary sclerosing cholangitis with brush cytology and FDG-PET. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1352–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahrendt SA, Pitt HA, Nakeeb A, Klein AS, Lillemoe KD, Kalloo AN, Cameron JL. Diagnosis and management of cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:357–367. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(99)80051-1. discussion 367–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rea DJ, Heimbach JK, Rosen CB, Haddock MG, Alberts SR, Kremers WK, Gores GJ, Nagorney DM. Liver transplantation with neoadjuvant chemoradiation is more effective than resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;242:451–458. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179678.13285.fa. discussion 458–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heimbach JK, Gores GJ, Haddock MG, Alberts SR, Pedersen R, Kremers W, Nyberg S, Ishitani MB, Rosen CB. Predictors of disease recurrence following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and liver transplantation for unresectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Transplantation. 2006;82:1703–1707. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000253551.43583.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis JT, Talwalkar JA, Rosen CB, Smyrk TC, Abraham SC. Precancerous bile duct pathology in end-stage primary sclerosing cholangitis, with and without cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:27–34. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181bc96f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boberg KM, Jebsen P, Clausen OP, Foss A, Aabakken L, Schrumpf E. Diagnostic benefit of biliary brush cytology in cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Association for the Study of the Liver: EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of cholestatic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2009;51:237–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, Nagorney DM, Boberg KM, Shneider B, Gores GJ. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases: Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:660–678. doi: 10.1002/hep.23294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gores GJ. Early detection and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2000;6(6 suppl 2):S30–S34. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.18688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trilianos P, Selaru F, Li Z, Gurakar A. Trends in pre-liver transplant screening for cholangiocarcinoma among patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Digestion. 2014;89:165–173. doi: 10.1159/000357445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prytz H, Keiding S, Björnsson E, Broomé U, Almer S, Castedal M, Munk OL. Dynamic FDG-PET is useful for detection of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with PSC listed for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2006;44:1572–1580. doi: 10.1002/hep.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Said K, Glaumann H, Bergquist A. Gallbladder disease in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2008;48:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang HL, Sun YG, Wang Z. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: diagnosis and indications for surgery. Br J Surg. 1992;79:227–229. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis JT, Talwalkar JA, Rosen CB, Smyrk TC, Abraham SC. Prevalence and risk factors for gallbladder neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: evidence for a metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:907–913. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213435.99492.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zielinski MD, Atwell TD, Davis PW, Kendrick ML, Que FG. Comparison of surgically resected polypoid lesions of the gallbladder to their pre-operative ultrasound characteristics. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Kuroda A, Muto T, Wada N. Large cholesterol polyps of the gallbladder: diagnosis by means of US and endoscopic US. Radiology. 1995;196:493–497. doi: 10.1148/radiology.196.2.7617866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azuma T, Yoshikawa T, Araida T, Takasaki K. Differential diagnosis of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder by endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Surg. 2001;181:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00526-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leung UC, Wong PY, Roberts RH, Koea JB. Gall bladder polyps in sclerosing cholangitis: does the 1-cm rule apply? ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:355–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosen CB, Nagorney DM, Wiesner RH, Coffey RJ, Jr, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Surg. 1991;213:21–25. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199101000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker NS, Rodriguez JA, Barshes NR, O’Mahony CA, Goss JA, Aloia TA. Outcomes analysis for 280 patients with cholangiocarcinoma treated with liver transplantation over an 18-year period. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:117–122. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1181–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasmussen HH, Fallingborg JF, Mortensen PB, Vyberg M, Tage-Jensen U, Rasmussen SN. Hepatobiliary dysfunction and primary sclerosing cholangitis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:604–610. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fausa O, Schrumpf E, Elgjo K. Relationship of inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Liver Dis. 1991;11:31–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soetikno RM, Lin OS, Heidenreich PA, Young HS, Blackstone MO. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:48–54. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broomé U, Bergquist A. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and colon cancer. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:31–41. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braden B, Halliday J, Aryasingha S, Sharifi Y, Checchin D, Warren BF, Kitiyakara T, Travis SP, Chapman RW. Risk for colorectal neoplasia in patients with colonic Crohn’s disease and concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Valle MB, Björnsson E, Lindkvist B. Mortality and cancer risk related to primary sclerosing cholangitis in a Swedish population-based cohort. Liver Int. 2012;32:441–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boonstra K, Weersma RK, van Erpecum KJ, Rauws EA, Spanier BW, Poen AC, van Nieuwkerk KM, Drenth JP, Witteman BJ, Tuynman HA, Naber AH, Kingma PJ, van Buuren HR, van Hoek B, Vleggaar FP, van Geloven N, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. EpiPSCPBC Study Group: Population-based epidemiology, malignancy risk, and outcome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2013;58:2045–2055. doi: 10.1002/hep.26565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boonstra K, van Erpecum KJ, van Nieuwkerk KM, Drenth JP, Poen AC, Witteman BJ, Tuynman HA, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is associated with a distinct phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2270–2276. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eaton JE, Talwalkar JA, Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis and advances in diagnosis and management. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:521–536. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rudolph G, Gotthardt D, Kloeters-Plachky P, Rost D, Kulaksiz H, Stiehl A. In PSC with dominant bile duct stenosis, IBD is associated with an increase of carcinomas and reduced survival. J Hepatol. 2010;53:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torres J, Pineton de Chambrun G, Itzkowitz S, Sachar DB, Colombel JF. Review article: colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:497–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh S, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Loftus EV, Jr, Talwalkar JA. Incidence of colorectal cancer after liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1361–1369. doi: 10.1002/lt.23741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sint Nicolaas J, de Jonge V, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, van Leerdam ME, Veldhuyzenvan Zanten SJ. Risk of colorectal carcinoma in post-liver transplant patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:868–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loftus EV, Jr, Aguilar HI, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Krom RA, Zinsmeister AR, Graziadei IW, Wiesner RH. Risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis following orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1998;27:685–690. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brentnall TA, Haggitt RC, Rabinovitch PS, Kimmey MB, Bronner MP, Levine DS, Kowdley KV, Stevens AC, Crispin DA, Emond M, Rubin CE. Risk and natural history of colonic neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:331–338. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eaton JE, Smyrk TC, Imam M, Pardi DS, Loftus EV, Jr, Owens VL, Talwalkar JA. The fate of indefinite and low-grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis colitis before and after liver transplantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:977–987. doi: 10.1111/apt.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tung BY, Emond MJ, Haggitt RC, Bronner MP, Kimmey MB, Kowdley KV, Brentnall TA. Ursodiol use is associated with lower prevalence of colonic neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:89–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pardi DS, Loftus EV, Jr, Kremers WK, Keach J, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid as a chemopreventive agent in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:889–893. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolf JM, Rybicki LA, Lashner BA. The impact of ursodeoxycholic acid on cancer, dysplasia and mortality in ulcerative colitis patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh S, Khanna S, Pardi DS, Loftus EV, Jr, Talwalkar JA. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid use on the risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1631–1638. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318286fa61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eaton JE, Silveira MG, Pardi DS, Sinakos E, Kowdley KV, Luketic VA, Harrison ME, Mc-Cashland T, Befeler AS, Harnois D, Jorgensen R, Petz J, Lindor KD. High-dose ursodeoxycholic acid is associated with the development of colorectal neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1638–1645. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lindberg BU, Broomé U, Persson B. Proximal colorectal dysplasia or cancer in ulcerative colitis. The impact of primary sclerosing cholangitis and sulfasalazine: results from a 20-year surveillance study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:77–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02234825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harnois DM, Gores GJ, Ludwig J, Steers JL, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH. Are patients with cirrhotic stage primary sclerosing cholangitis at risk for the development of hepatocellular cancer? J Hepatol. 1997;27:512–516. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80356-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zenouzi R, Weismüller TJ, Hübener P, Schulze K, Bubenheim M, Pannicke N, Weiler-Normann C, Lenzen H, Manns MP, Lohse AW, Schramm C. Low risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1733–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rizvi S, Borad MJ, Patel T, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma: molecular pathways and therapeutic opportunities. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:456–464. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1394144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spirlì C, Fabris L, Duner E, Fiorotto R, Ballardini G, Roskams T, Larusso NF, Sonzogni A, Okolicsanyi L, Strazzabosco M. Cytokine-stimulated nitric oxide production inhibits adenylyl cyclase and cAMP-dependent secretion in cholangiocytes. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:737–753. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cadamuro M, Nardo G, Indraccolo S, Dall’Olmo L, Sambado L, Moserle L, France-schet I, Colledan M, Massani M, Stecca T, Bassi N, Morton S, Spirli C, Fiorotto R, Fabris L, Strazzabosco M. Platelet-derived growth factor-D and Rho GTPases regulate recruitment of cancer-associated fibroblasts in cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;58:1042–1053. doi: 10.1002/hep.26384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cadamuro M, Vismara M, Brivio S, Furlanetto A, Strazzabosco M, Fabris L. JNK signaling activated by platelet-derived growth factor-D (PDGF-D) stimulates secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C) by cancer-associated fibroblasts to promote lymphangiogenesis and early metastasization in cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S389. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ochsenkühn T, Bayerdörffer E, Meining A, Schinkel M, Thiede C, Nüssler V, Sackmann M, Hatz R, Neubauer A, Paumgartner G. Colonic mucosal proliferation is related to serum deoxycholic acid levels. Cancer. 1999;85:1664–1669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wohl P, Hucl T, Drastich P, Kamenar D, Spicak J, Honsova E, Sticova E, Lodererova A, Matous J, Hill M, Wohl P, Kucera M. Epithelial markers of colorectal carcinogenesis in ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2234–2241. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]