Abstract

Patient: Male, 68

Final Diagnosis: Invasive esophageal candiasis

Symptoms: Chest discomfort

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Infectious Diseases

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Invasive candidiasis is a potential problem for patients receiving long-term immunosuppressive treatment. Psoriatic arthritis is one of many chronic diseases that can be successfully treated with immunosuppressive drugs, in spite of a documented and accepted risk for infectious complications. Critical awareness of possible infection must be part of the surveillance of such patients.

Case Report:

This is the case of a 68-year-old Norwegian male, treated with long-term immunosuppression for psoriatic arthritis, hospitalized with acute subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema of unknown cause. He died of acute respiratory failure with circulatory collapse shortly after admission. The autopsy revealed mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema and a mediastinal abscess containing Candida with probable entrance from the esophagus.

Conclusions:

We consider invasive candidiasis of the esophagus to be the cause of both the chronic abscess and the acute mediastinal emphysema. This case illustrates the importance of awareness of invasive candidiasis as a possible complication in a patient with long-term immunosuppression.

MeSH Keywords: Arthritis, Psoriatic; Autopsy; Candidiasis; Immunosuppression

Background

There are more than 20 species of Candida. The species differ considerably in virulence, C. parapsilosis and C. krusei are less virulent than C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, and C. pseudohyphae [1]. Candida species normally live in the gastrointestinal tract and on skin as part of a normal microbiotic flora without causing disease [2]. Invasive candidiasis, on the other hand, is the most common fungal disease among immunosuppressed patients. It comprises both candidemia and deep-seated tissue candidiasis. Mortality among patients with invasive candidiasis, even when receiving antifungal therapy, is as high as 40% [3]. There are a number of risk factors for critical illness, such as treatment in long-term intensive care units, repeat abdominal surgery, acute necrotizing pancreatitis, hematologic malignant disease, solid-organ transplantation, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, presence of central vascular catheter, total parenteral nutrition, hemodialysis, and glucocorticoid or chemotherapy treatment [4–6]. The methods used for diagnosing invasive candidiasis include direct detection (blood and tissue cultures) and indirect detection (surrogate markers and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays) [7–9]. Invasive candidiasis is a potential problem for the majority of immunosuppressive patients. The diagnosis and early treatment are still the basis of the overall approach to the fungal invasive infection after immunosuppressive treatment.

Case Report

The patient was a 68-year-old Norwegian male, diagnosed at the age of 50 with seropositive psoriatic arthritis, treated with long-term medication with prednisolone and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS); he had also received methotrexate for 5 years, which was stopped 10 years ago. At the age of 58, he was operated on bilaterally for total knee replacement. He was treated with thyroxin because of hypothyroidism and received salbutamol therapy due to bronchial asthma in recent years. After his first knee surgery, he suffered chest pain and was diagnosed with pneumonia and a transient pericarditis with atrial fibrillation. However, echocardiography showed normal findings without cardiac disease. The year before, he had been admitted to hospital with chest discomfort without findings of coronary ischemia. Repeat radiologic examination over more than 10 years had, however, shown findings interpreted as a ventricular hernia. A gastroscopy performed last year showed a ventricular hernia, with otherwise normal findings. Only 12 days before his last admission to hospital, he underwent right-sided total hip replacement at the Department of Surgery because of coxarthrosis. The operation was performed with spinal anesthesia, without any medical complications. The patient was admitted in the morning at his local hospital with acute dyspnea, with chest and back pain during the night before admission. His systemic blood pressure was low (103/73), heart rate 105, and respiratory rate 30/min. His skin was described as pale, cyanotic, and sweating. He received symptomatic therapy, including oxygen and antibiotics, with suspicion of pulmonary infection. During the day, his condition worsened, with increased respiratory frequency and lowered oxygen saturation, and subcutaneous emphysema occurred. Therefore, on the same evening he was transferred to Førde Central Hospital with a diagnosis of acute respiratory insufficiency. A chest X-ray shortly before showed pneumomediastinum, without signs of pneumothorax. A CT scan after admission showed a large air-containing cystic structure within the mediastinum, and increasing mediastinal emphysema (Figure 1). Blood cultures were negative for bacteria and for Candida species. In spite of treatment at the hospital’s intensive care unit, his respiratory insufficiency worsened and he died the next morning. Laboratory test results are given in Tables 1 and 2.

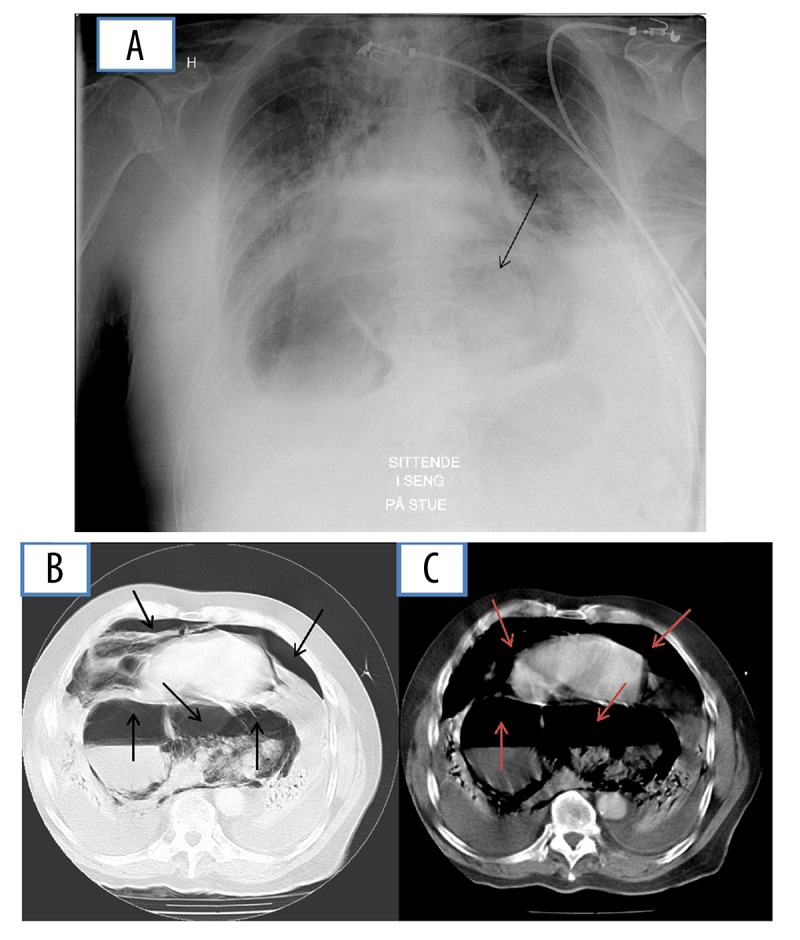

Figure 1.

(A) X-ray and (B, C) contrast-enhanced CT illustrating areas with an air-containing filling in the mediastinum, previously perceived as ventricular hernia (A–C: lower arrows). Acute mediastinal emphysema (B, C: upper arrows).

Table 1.

Day 1: Summary of laboratory test results.

| Test | Result | Unit | Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blodtype antistoff screening | Neg | (neg) | |

| Leukocytes | 10.7 | 109/L | 4.0–11.0 |

| Erythrocytes | 4.8 | 1012/L | 3.8–5.8 |

| Thrombocytes | 309 | 109/L | 150–400 |

| Hemoglobin | 14.1 | g/dL | 12.6–17.4 |

| EVF | 0.45 | L | 0.40–0.52 |

| SR | 32 | mm/h | <21 |

| Sodium | 144 | mmol/L | 136–146 |

| Potassium | 5.0 | mmol/L | 3.5–5.0 |

| Creatinine | 211 | µmol/L | <120 |

| Glucose | 6.7 | mmol/L | 3.7–6.0 (fasting) |

| CRP | 128 | mg/L | <10 |

| AST | 23 | U/L | <50 |

| ALT | 30 | U/L | <50 |

| LD | 626 | U/L | <500 |

| ALP | 118 | U/L | <330 |

| GT | 44 | U/L | <80 |

| Albumin | 40 | U/L | <200 |

| MCV | 34 | g/L | 35–50 |

Table 2.

Day 2: Summary of laboratory test results.

| Test | Result | Unit | Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes | 11.9 | 109/L | 4.0–11.0 |

| Hemoglobin | 13.1 | g/dL | 12.6–17.4 |

| Sodium | 139 | mmol/L | 136–146 |

| Creatinine | 202 | µmol/L | <120 |

| Glucose | 5.8 | mmol/L | 3.7–6.0 (fasting) |

| CRP | 292 | mg/L | <10 |

| Urine bacterial culture | Negative | Negative | |

| Blood cultures | Negative | Negative |

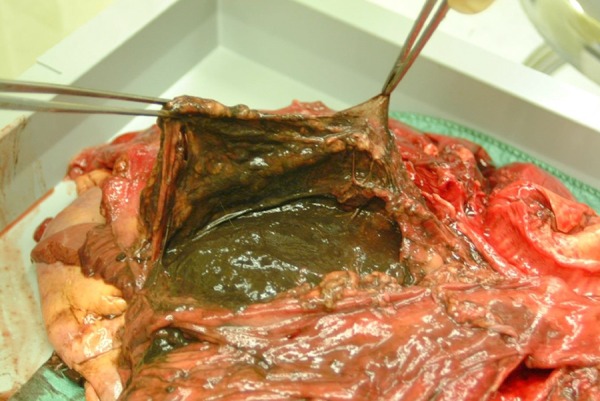

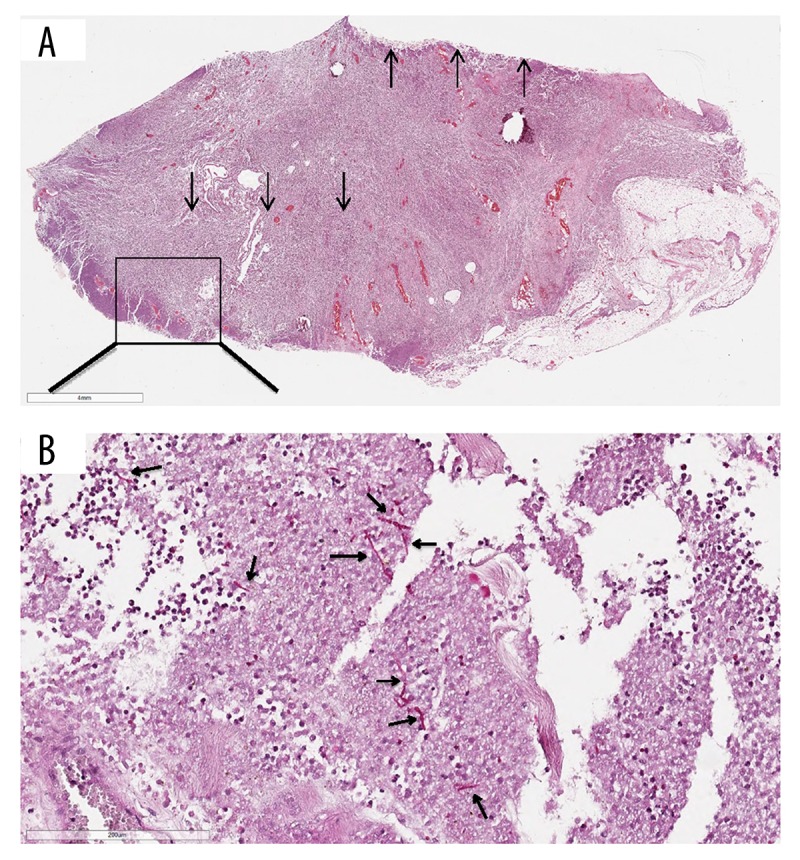

Autopsy findings are summarized in Table 3. Findings of subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema were confirmed. Examination of the thoracic cavity revealed a chronic abscess with cystic degeneration (Figure 2), with a diameter of approximately 8 cm in the caudal part of the mediastinum, behind the heart and in front of the esophagus. The abscess was found to be firmly adherent to a large proportion of the oesophagus, with black-colored contents. In spite of the close relationship between the oesophagus and the large abscess, no macroscopic ulcer or perforation of the oesophagus wall were evident. There was no pulmonary emphysema and no signs of rib fractures or lesions of the airways, and significant pneumothorax could not be demonstrated, nor was there any sign of pulmonary embolism. No ventricular hernia was found. On microscopic examination, sections from the mediastinal lesion showed pronounced inflammation, with large amounts of neutrophilic granulocytes and abscess formation. Oesophageal structures formed part of the abscess wall. Within the lesion, PAS-positive organisms with morphology of the fungus Candida was found (Figure 3). Furthermore, necrotic substance within the abscess contained PAS-positive cell walls, consistent with food remnants. A small mediastinal lymph node showed acute lymphadenitis. Specimens for bacterial or fungus cultures were not provided.

Table 3.

Main and secondary diagnosis at autopsy.

| Main diagnosis |

| Mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema; clinically with respiratory failure. |

| Mediastinal abscess, containing candida; entrance from the esophagus |

| Psoriatic arthritis; treated with immunosuppressive medications for many years |

| Secondary diagnosis |

| Gastritis |

| Pericardial adhesion |

| Minor old cerebral infarctions |

| Kidneys with acute ischemic tubular necrosis (shock kidneys) |

| Atrophic thyroid gland |

| Total prosthesis in right hip joint and bilateral total knee prosthesis |

| Spinal compression fractures with osteoporosis |

Figure 2.

Macroscopic view of mediastinal abscess.

Figure 3.

The histological specimens were fixed in 4% neutral buffered formaldehyde, paraffin-embedded, and cut into 4-micrometer sections. Sections were stained by hematoxylin-eosin and selected special stains including PAS. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin – stained section from wall of the esophagus with pronounced inflammation and abscess formation. (B) PAS staining shows invasive pseudohyphae in the abscess, with morphology consistent with Candida. ↑ – towards wall of esophagus; ↓ – wall of abscess.

Discussion

We present a case of lethal, acute mediastinal emphysema in a 68-year-old male, for many years treated with immunosuppression against psoriatic arthritis. From autopsy findings, in conjunction with clinical information, it was suggested that death was due to a massive mediastinal emphysema with respiratory failure and circulatory collapse. The autopsy revealed a hitherto undiagnosed mediastinal abscess that was firmly attached to the oesophageal wall, and with the finding of Candida during microscopic examination. We consider, therefore, invasive candidiasis of the esophagus to be the probable cause of the chronic abscess. Furthermore, we assume that the same process of chronic inflammatory involvement of the oesophageal wall explains the onset of the acute mediastinal emphysema, by microscopic rupture(s) of the oesophagus wall. Importantly, no signs of pulmonary or chest-wall lesions could be demonstrated at autopsy, although a pulmonary/airway source for the soft-tissue emphysema was suspected by the clinicians. Although he had received surgical treatment with hip replacement 12 days before admission, we were not able to find any obvious post-operative complications; it could be assumed however, that the patient in this clinical phase would be more vulnerable to any additional trauma. According to previous clinical reports, an air-containing filling in the mediastinum was demonstrated many years ago, perceived as a ventricular hernia. Follow-up radiologic controls showed persistence of this finding. No hernia was found post-mortem, however, and review of X-ray pictures support that this “hernia” corresponded to the mediastinal abscess demonstrated on autopsy. While the diameter of the abscess at autopsy was estimated to be about 8 cm, photographs taken during the session indicated an even larger lesion; by radiologic assessment of CT pictures taken shortly before death, the lesion was measured as being 11×20×9 cm. Invasive candidiasis is a potential problem for many immunosuppressed patients [10]. Immunosuppression is a treatment option for psoriatic arthritis, despite significant morbidity and mortality due to infectious complications [10]. The Candida species found during microscopy was not further analyzed because tissue culture was not performed. We find it highly probable, however, that the organism was C. albicans, as this is by far the dominant Candida species in our geographic region [11]. General risk factors of invasive candidiasis independent of our case report are critical illness, with particular risk among patients with long-term ICU stay and abdominal surgery. Particular risk also exists among patients who have anastomotic leakage or have had repeat laparotomies, acute necrotizing pancreatitis, hematologic malignant disease, solid-organ transplantation, and solid-organ tumors. Other patients at risk include neonates, particularly those with low birth weight and preterm infants, and patients receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics, presence of central vascular catheter, total parenteral nutrition, hemodialysis, glucocorticoid use or chemotherapy for cancer, and Candida colonization, particularly if multifocal [4–6]. Our patient was initially treated with antibiotics upon suspicion of pneumonia, but without clinical effect, and a bacterial infection was never documented. The diagnosis of Candida infection was made post-mortem, and the patient died before a potential antifungal therapy could have been effective. Early diagnosis and treatment are still the basis of the overall approach to fungal invasive infections in patients treated with immunosuppressive drugs [12,13]. We believe our case illustrates the importance of careful vigilance for infectious diseases, especially fungus infection, in immunocompromised patients. Physicians should also keep this possibility in mind if a patient with systemic infection does not respond to antibacterial treatment.

Conclusions

The autopsy performed in a case of lethal, acute mediastinal emphysema in a 68-year-old man, for many years treated with immunosuppression against psoriatic arthritis, revealed a hitherto undiagnosed mediastinal abscess due to chronic Candida infection. We consider invasive candidiasis of the esophagus to be the probable cause of both the chronic abscess and the acute mediastinal emphysema. This case illustrates the importance of awareness of invasive candidiasis as a possible complication in a patient with long-term immunosuppression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sverre Stenberg, MD, Department of Radiology and Reidar Hjetland, MD, Department of Microbiology, at Førde Central Hospital for advice and assistance in this publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and received no financial support in this study.

References:

- 1.Arendrup M, Horn T, Frimodt-Møller N. In vivo pathogenicity of eight medically relevant Candida species in an animal model. Infection. 2002;30:286–91. doi: 10.1007/s15010-002-2131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappas PG. Invasive candidiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006;20(3):485–506. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kullberg BJ, Arendrup MC. Invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1445–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1315399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleveland AA, Harrison LH, Farley MM, et al. Declining incidence of candidemia and the shifting epidemiology of Candida resistance in two US metropolitan areas, 2008–2013: Results from population-based surveillance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arendrup MC, Sulim S, Holm A, et al. Diagnostic issues, clinical characteristics, and outcomes for patients with fungemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3300–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00179-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lortholary O, Renaudat C, Sitbon K, et al. Worrisome trends in incidence and mortality of candidemia in intensive care units (Paris area, 2002–2010) Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1303–12. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3408-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuenca-Estrella M, Verweij PE, Arendrup MC, et al. ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: Diagnostic procedures. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl. 7):9–18. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamoth F, Cruciani M, Mengoli C, et al. β-Glucan antigenemia assay for the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections in patients with hematological malignancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies from the Third European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL-3) Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:633–43. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikulska M, Calandra T, Sanguinetti M, et al. The use of mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibodies in the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis: Recommendations from the Third European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Crit Care. 2010;14:R222. doi: 10.1186/cc9365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: A population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(3):586–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandven P, Bevanger L, Digranes A, et al. Candidemia in Norway (1991 to 2003): results from a nationwide study. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1977–81. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markowski J, Helbig G, Widziszowska A, et al. Fungal colonization of the respiratory tract in allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: A study of 573 transplanted patients. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:1173–80. doi: 10.12659/MSM.893267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olatinwo O, Ivonye C, Jamched U, et al. Severe unexplained HIV seronegative immune suppression (SUHIS) with invasive aspergillosis and candidiasis. Am J Case Rep. 2008;9:280–84. [Google Scholar]