Abstract

Coccidiosis is the bane of the poultry industry causing considerable economic loss. Eimeria species are known as protozoan parasites to cause morbidity and death in poultry. In addition to anticoccidial chemicals and vaccines, natural products are emerging as an alternative and complementary way to control avian coccidiosis. In this review, we update recent advances in the use of anticoccidial phytoextracts and phytocompounds, which cover 32 plants and 40 phytocompounds, following a database search in PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Four plant products commercially available for coccidiosis are included and discussed. We also highlight the chemical and biological properties of the plants and compounds as related to coccidiosis control. Emphasis is placed on the modes of action of the anticoccidial plants and compounds such as interference with the life cycle of Eimeria, regulation of host immunity to Eimeria, growth regulation of gut bacteria, and/or multiple mechanisms. Biological actions, mechanisms, and prophylactic/therapeutic potential of the compounds and extracts of plant origin in coccidiosis are summarized and discussed.

1. Introduction

Each year, over 50 billion chickens are raised as a source of meat, accounting for over one-third of protein food for humans [1]. However, poultry production is often confronted by avian coccidiosis, flu, and other infectious diseases [1]. Avian coccidiosis is characterized as an infectious protozoan disease caused by gut parasites of the genus Eimeria (Coccidia subclass) [2]. So far, nine Eimeria species, E. acervulina, E. brunetti, E. maxima, E. necatrix, E. praecox, E. mitis, E. tenella, E. mivati, and E. hagani, have been identified from chickens [3]. These parasites can infect and multiply within the mucosal epithelia in different parts of bird guts via oral route. As a result, they cause gut damage (i.e., inflammation, hemorrhage, diarrhea, etc.), morbidity, and mortality in poultry [4]. This disease annually causes a global loss of over 2.4 billion US dollars in the poultry industry, including poor growth performance, replacement of chicks, and medication [1]. Current approaches to constrain avian coccidiosis include anticoccidial chemicals, vaccines, and natural products. Anticoccidial chemicals, coccidiocides, coccidiostats, and ionophores, have long been used as a mainstream strategy to control avian coccidiosis in modern poultry production [5]. Although this strategy is cost-effective and successful, the presence of drug resistance and public demands for residue-free meat has encouraged development of alternative control strategies [5]. Moreover, in European countries, the prophylactic use of anticoccidial chemicals as feed additives has been strictly limited since 2006 and a full ban has been proposed to be effective in 2021 (Council Directive of 2011/50/EU of the European Council). To cope with this global situation, vaccination, composed of one or more strains of wild-type or attenuated Eimeria species, is successfully developed as another approach to prevent coccidiosis though their cross-species protection and efficacy may need to be improved. Natural products are emerging as an attractive way to combat coccidiosis. Currently, there are at least four plant products commercially available on the market and they can be used as anticoccidial feed additives in chickens and/or other animals, including Cocci-Guard (DPI Global, USA) [6], a mixture of Quercus infectoria, Rhus chinensis, and Terminalia chebula (Kemin Industries, USA) [7], Apacox (GreenVet, Italy) [8], and BP formulation made up of Bidens pilosa and other plants (Ta-Fong Inc., Taiwan) [9]. Besides, investigation of the compounds and/or their derivatives present in anticoccidial plants may inspire the research and development of anticoccidial chemicals. One successful example is halofuginone, a synthetic halogenated derivative of febrifugine, which was initially identified from the antimalarial plant, Chang Shan (Dichroa febrifuga) [10]. Despite the aforesaid merits of natural products, several challenges in the anticoccidial use of natural products such as anticoccidial efficacy, identification of active compounds, mechanism, safety, and cost-effectiveness of plant extracts and compounds need to be overcome prior to further applications.

Several reviews were published on the plant extracts and their phytochemicals for avian coccidiosis [1, 11, 12]. To complement and update recent progress on the anticoccidial properties of plant extracts and/or compounds, here we have updated the plants and compounds related to anticoccidial activity, chemistry, and prophylactic/therapeutic potential. New views on the anticoccidial action of plants and compounds are also discussed. Common terms and their definitions used in this paper are presented as follows.

Anticoccidial Chemicals. These are chemicals which kill coccidia (coccidiocides) or slow their growth (coccidiostats). Ionophores are a class of polyether chemicals which interfere with ion transport, leading to the death of coccidia.

Phytoextract/Plant Extract. They are a collection of plant ingredients obtained by means of solvent extraction.

Phytocompound/Phytochemical. This refers to any chemical synthesized by plants.

Natural Products. These are compounds/chemicals found in nature including plants, animals, and minerals.

Coccidia. It is a subclass of microscopic, spore-forming, single-celled protozoan parasites belonging to the apicomplexan class.

Eimeria. This is a genus of apicomplexan parasites that include various species capable of causing gut disease in poultry and other animals.

1.1. Life Cycle of Eimeria Species

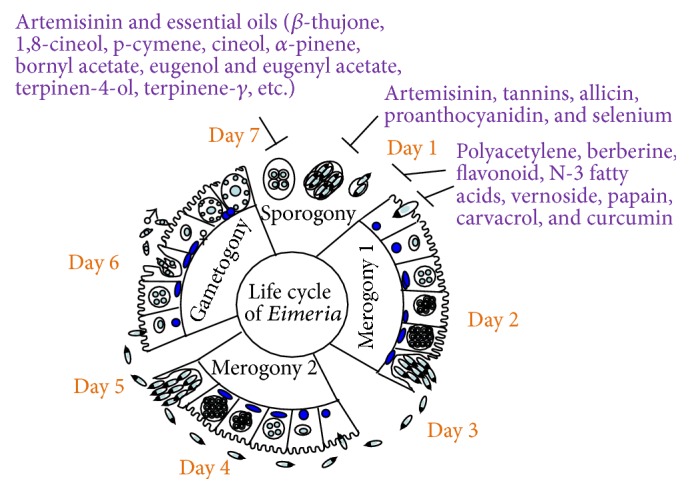

As illustrated in Figure 1, Eimeria species have a complex life cycle, consisting of three developmental stages (sporogony, schizogony/merogony, and gametogony). Oocysts excreted in poultry feces sporulate in a favourable environment with high humidity at 25–30°C. Once sporulating oocysts are ingested by birds, physical and chemical agents in their digestive tracts are released and mature infectious sporozoites form sporocysts. The sporozoites enter epithelial cells in the gut, depending on the specific Eimeria species, and form trophozoites and, later, schizonts during schizogony/merogony [13]. Merozoites, released from the schizont, can penetrate into the epithelia and continue this merogony stage 2 to 3 times in order to increase the cell number of merozoites at the asexual stage of reproduction. Alternatively, merozoites may enter the sexual stage of reproduction by forming male microgametes, the equivalent of sperm, and female macrogametes, the equivalent of oocytes, in host cells. Following fertilization, the zygotes develop into oocysts and are excreted into poultry stool. Eimeria species may require 4–7 days to complete their entire life cycles [14]. Thus, the asexual and sexual stages of reproduction in the Eimeria life cycle have been targeted by anticoccidial compounds [4].

Figure 1.

Plant compounds target different stages of the life cycle of Eimeria species. Eimeria species take 4–7 days to complete their life cycles. They have 3 different developmental stages in poultry: sporogony, merogony, and gametogony. This scheme is modified from the previous publication [40]. Different phytocompounds inhibit the growth of Eimeria species at sporogony and merogony stages.

1.2. Prophylaxis and Therapy for Avian Coccidiosis

Coccidiosis is one of the major problems in intensive poultry farming [1]. In contrast to anticoccidial chemicals and vaccines, the use of medicinal plants and phytocompounds as natural remedies for avian coccidiosis has become an alternative strategy that is easily embraced by eco- and health-conscious consumers. Of course, this strategy is also in compliance with the “anticoccidial chemical-free” regulation enacted by the European Union (Council Directive of 2011/50/EU). Plants produce a broad-spectrum variety of phytochemicals such as phenolics, polyacetylenes, alkaloids, polysaccharides, terpenoids, and essential oils with a large number of bioactivities [12, 15, 16]. Different reports on the use of medicinal plants for diseases suggest that they have the potential to “kill several birds with one stone” because they contain multiple phytochemicals and can intervene in multiple disease-related signalling pathways [17].

2. Plants and Compounds for Avian Coccidiosis

Over 300,000 species of flowering plants have been recorded worldwide. So far, less than 1% of them have been explored for use against protozoan diseases [18]. In this section, a total of 68 plants and phytocompounds, which were scientifically tested for suppression of Eimeria species, are described and discussed [1, 9, 11, 12]. Table 1 lists 32 anticoccidial plants whose active compounds and modes of action need to be elucidated: Sophora flavescens (Fabaceae), Sinomenium acutum (Menispermaceae), Quisqualis indica (Combretaceae), Pulsatilla koreana (Ranunculaceae), Ulmus macrocarpa (Ulmaceae), Artemisia asiatica (Asteraceae), Gleditsia japonica (Fabaceae), Melia azedarach (Meliaceae), Piper nigrum (Piperaceae), Urtica dioica (Urticaceae), Artemisia sieberi (Asteraceae), Lepidium sativum (Brassicaceae), Foeniculum vulgare (Apiaceae), Morinda lucida (Rubiaceae), Commiphora swynnertonii (Burseraceae), Moringa oleifera (Moringaceae), Origanum spp. (Lamiaceae), Laurus nobilis (Lauraceae), Lavandula stoechas (Lamiaceae), Musa paradisiaca (Musaceae), Moringa stenopetala (Moringaceae), Solanum nigrum (Solanaceae), Mentha arvensis (Lamiaceae), Moringa indica (Moringaceae), Melia azadirachta (Meliaceae), Tulbaghia violacea (Amaryllidaceae), Vitis vinifera (Vitaceae), Artemisia afra (Asteraceae), Quercus infectoria (Fagaceae), Rhus chinensis (Anacardiaceae), and Terminalia chebula (Combretaceae). Details about active phytocompounds present in the other anticoccidial plants and their mechanisms are summarized in Tables 2 –4.

Table 1.

Anticoccidial properties of plants.

| S. number | Plant species (usage) | Usage∗ | Eimeria species | Parameter measured | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S. flavescens | Decoction | Et | WG ↑, OC ↓, BD ↓, LS ↓, and M ↓ | [41] |

| 2 | S. acutum | Decoction | Et | WG ↑, OC ↓, BD ↓, LS ↓, and M ↓ | [41] |

| 3 | Q. indica | Decoction | Et | WG ↑ and M ↓ | [41] |

| 4 | P. koreana | Decoction | Et | WG ↑ and LS ↓ | [41] |

| 5 | U. macrocarpa | Decoction | Et | LS ↓ | [41] |

| 6 | A. asiatica | Decoction | Et | WG ↑ and LS ↓ | [41] |

| 7 | G. japonica | Decoction | Et | LS ↓ | [41] |

| 8 | M. azedarach | Decoction | Et | WG ↑ and LS ↓ | [41] |

| 9, 10 | P. nigrum and U. dioica | Ethanolic extract | Mixed species | OC ↓ | [42] |

| 11 | A. sieberi | Petroleum ether extract | Et | OC ↓, BD ↓, LS ↓, and M ↓ | [43–45] |

| 12 | L. sativum | Ethanolic extract | Et | OC ↓, LS ↓, M ↓, and WG ↑ | [46] |

| 13 | F. vulgare | Ground leaves powder | Et | OC ↓, LS ↓, M ↓, WG ↑, and BD ↓ | [47] |

| 14 | M. lucida | Ground leaves powder | Mixed species | WG ↑ and OC ↓ | [48] |

| 15 | C. swynnertonii | Ethanolic resinous extract | Oocysts | OC ↓, M ↓, and WG ↑ | [49] |

| 16 | M. oleifera | Acetone leaves extract | Mixed species | WG ↑ and OC ↓ | [50] |

| 17 | Origanum spp. | Essential oil | Mixed species | OC ↓, LS ↓, M ↓, and WG ↑ | [51] |

| 18 | L. nobilis | Essential oil | Mixed species | OC ↓, LS ↓, M ↓, and WG ↑ | [51] |

| 19 | L. stoechas | Essential oil | Mixed species | OC ↓, LS ↓, M ↓, and WG ↑ | [51] |

| 20 | M. paradisiaca | Methanolic extract | Et | OC ↓ and PCV ↑ | [52] |

| 21 | M. stenopetala | Ground leaves powder | Et | OC ↓, LS ↓, and WG ↑ | [53] |

| 22 | S. nigrum | Decoction | Et | WG ↑ and FC ↑ | [54] |

| 23 | M. arvensis | Decoction | Et | WG ↑ and FC ↑ | [54] |

| 24 | M. indica | Decoction | Et | WG ↑ and FC ↑ | [54] |

| 25 | M. azedarach | Fresh juice | Mixed species | OC ↓ | [55] |

| 26 | T. violacea | Acetone extract | Et | OC ↓, LS ↓, and FC ↑ | [56] |

| 27 | V. vinifera | Acetone extract | Et | OC ↓, LS ↓, and FC ↑ | [56] |

| 28 | A. afra | Acetone extract | Et | OC ↓, LS ↓, and FC ↑ | [56] |

| 29 | G. rhois | Ground powder | Et | OC ↓, LS ↓, M ↓, and WG ↑ | [57] |

| 30, 31, 32 | Q. infectoria, R. chinensis, and T. chebula | ? | Et, Em, and Ea | OC ↓, LS ↓, and M ↓ | [7] |

Et: E. tenella; Ea: E. acervulina; Ema: E. maxima; Eb: E. brunetti; En: E. necatrix; Emi: E. mivati; WG: body weight gain; OC: oocyst count; FC: feed consumption; M: mortality; EO: essential oil; BD: bloody diarrhea; FCR: feed conversion ratio; LS: lesion scores; ↑: improvement/increase/higher; ↓: decrease/lower; PCV: packed cell volume; ∗: whole plants and/or aerial parts of plants were used for tests unless indicated otherwise; ?: unknown.

Table 2.

Phytochemicals interfering with the life cycle of Eimeria species.

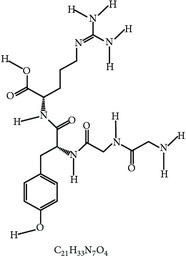

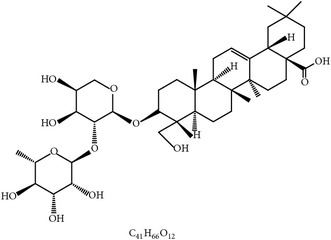

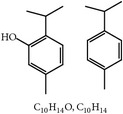

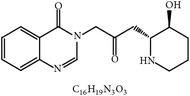

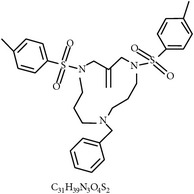

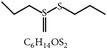

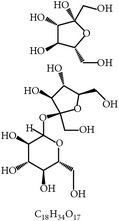

| S. number | Compound | Structure and formula | Plant | Mechanism | Eimeria species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Artemisinin |

|

A. annua | Inhibition of oocyst wall formation and sporulation via oxidative stress | Et, Ea, and Ema | [20–23, 58] |

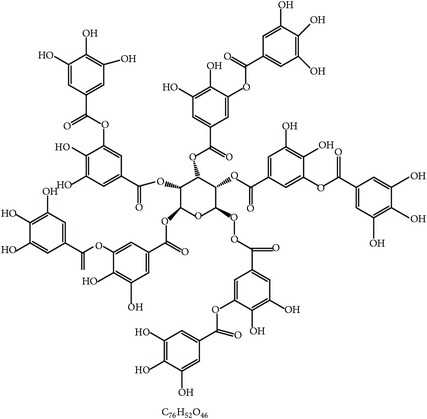

| 2 | Tannin |

|

P. radiata | Inhibition of sporulation | Et, Ea, and Ema | [25] |

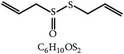

| 3 | Allicin |

|

A. sativum | Inhibition of sporozoites | Et | [26, 28] |

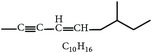

| 4 | Polyacetylene |

|

B. pilosa | Inhibition of sporozoites; immune modulation | Et | [8, 9] |

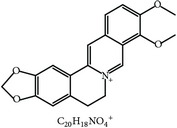

| 5 | Berberine |

|

A. lyceum | Inhibition of sporozoites by oxidative stress | Et | [59] |

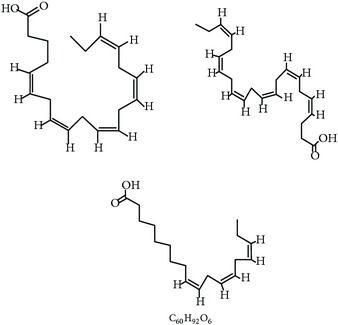

| 6 | N-3 fatty acids |

|

L. usitatissimum | Oxidative stress | Et | [21] |

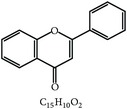

| 7 | Flavonoid |

|

A. conyzoides | Oxidative stress | Et | [31] |

| 8 | Vernoside |

|

V. amygdalina | Oxidative stress | Et | [32] |

| 9 | Papain |

|

C. papaya | Digestion of sporozoites in caeca | Et | [32] |

| 10 | Betaine |

|

O. vulgare | Stabilizing intestinal structure and function | Et, Ea, and Ema | [25, 36] |

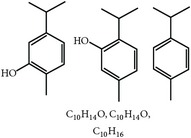

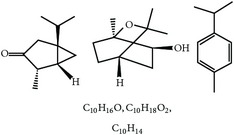

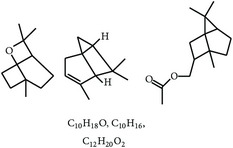

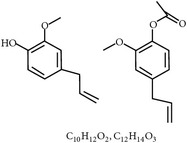

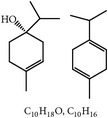

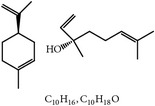

| 11 | Essential oil (carvacrol, thymol, and terpinene-γ) |

|

O. compactum | Destruction of sporozoites | Eimeria species | [12, 60] |

| 12 | Essential oil (β-thujone, 1,8-cineol, and p-cymene) |

|

A. absinthium | Prevention of oocyst development | Eimeria species | [61, 62] |

| 13 | Essential oil (cineol, α-pinene, and bornyl acetate) |

|

R. officinalis | Antioxidant and destruction of oocysts | Eimeria oocysts | [61, 63, 64] |

| 14 | Saponin |

|

M. cordifolia, M. citrifolia, M. arboreus, and C. tetragonoloba | Destruction of oocysts and parasites | Et | [35] |

| 15 | Essential oil (eugenol and eugenyl acetate) |

|

S. aromaticum | Destruction of oocysts | Et | [51, 61] |

| 16 | Essential oil (terpinen-4-ol and terpinene-γ) |

|

M. alternifolia | Destruction of oocysts | Eimeria oocysts | [61, 65] |

| 17 | Essential oil (limonene and linalool) |

|

C. sinensis | Destruction of oocysts | Eimeria oocysts | [61, 66] |

| 18 | Essential oil (thymol and p-cymene) |

|

T. vulgaris | Destruction of oocysts | Eimeria oocysts | [12, 61] |

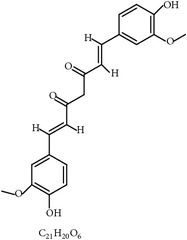

| 19 | Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) |

|

C. longa | Inhibition of sporozoites; immune modulation | Et and Ema | [21, 67] |

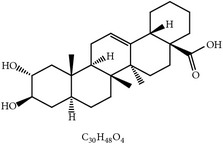

| 20 | Maslinic acid |

|

O. europaea | ? | Et | [37] |

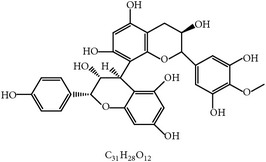

| 21 | Proanthocyanidin |

|

Grape seed | Antioxidant | Et | [38] |

| 22 | Selenium | ? | C. sinensis | Inhibition of sporulation | Et, Ea, and Ema | [30] |

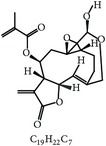

| 23 | Febrifugine |

|

D. febrifuga | Inhibition of multiplication | Et | [10, 39, 68] |

Et: E. tenella; Ea: E. acervulina; Ema: E. maxima; Eb: E. brunetti; En: E. necatrix; Emi: E. mivati; ?: unknown.

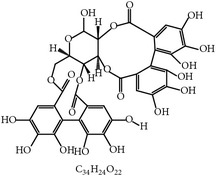

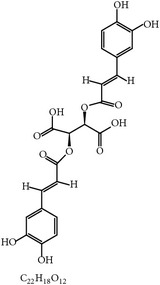

Table 3.

Phytochemicals regulating host immunity against Eimeria species.

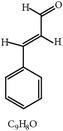

| S. number | Compound | Structure and formula | Plant | Mechanism | Eimeria species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

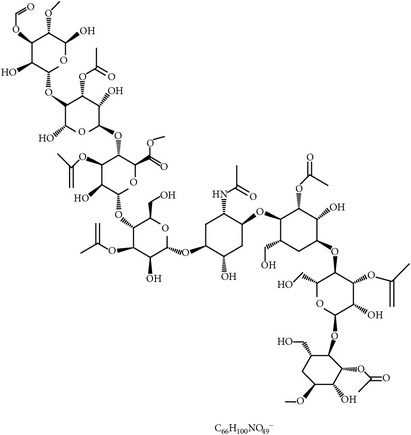

| 24 | Arabinoxylans |

|

T. aestivum | Immune stimulation | Et, Ea, Ema, and En | [69] |

| 25 | Cinnamaldehyde |

|

C. cassia | Immune modulation | Et, Ea, and Ema | [70, 71] |

| 26 | Acemannan |

|

A. vera | Immune stimulation | Eimeria spp. | [72, 73] |

| 27 | Lectin |

|

F. fraxinea | Immune stimulation | Ea | [74] |

| 28 | Propyl thiosulfinate |

|

A. sativum | Protective immunity | Ea | [75, 76] |

| 29 | Tannin (pedunculagin) |

|

A. officinalis | Immune stimulation | Eimeria spp. | [77] |

| 30 | Chicoric acid |

|

E. purpurea | Immune stimulation | Eimeria spp. | [78, 79] |

| 31 | Mushroom polysaccharide | ? | L. edodes and T. fuciformis | Immune stimulation | Et | [80] |

| 32 | Phenolics compounds | ? | P. salicina | Immune stimulation | Ea | [81, 82] |

Et: E. tenella; Ea: E. acervulina; Ema: E. maxima; Eb: E. brunetti; En: E. necatrix; ?: unknown.

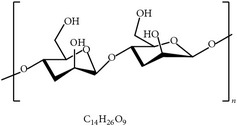

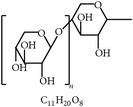

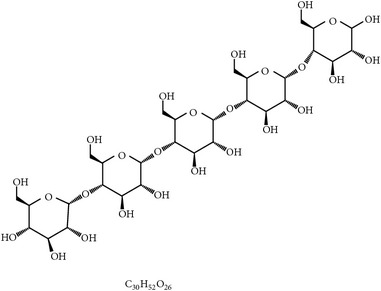

Table 4.

Phytochemicals with prebiotic function for gut microbiota.

| S. number | Prebiotics | Chemical structure | Plant | Effects on poultry microbiota | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

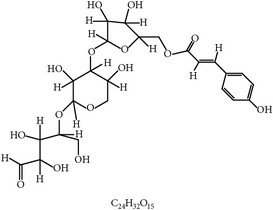

| 33 | Inulin |

|

Chicory | Enhancing gut microflora, morphology, and immunity | [83, 84] |

| 34 | Mannan-oligosaccharides |

|

Fungi and yeast | Increasing digestion and gut microbiota | [85, 86] |

| 35 | Xylooligosaccharides |

|

Bamboo shoots, fruits, vegetables, and wheat bran | Increasing Lactobacillus in colon | [87] |

| 36 | Isomaltooligosaccharides |

|

Starch | Increasing cecal probiotics and fatty acids | [88, 89] |

| 37 | Soy oligosaccharides | ? | Soybean | Changing microbiota | [90] |

| 38 | Pyrodextrins | ? | Sucrose | Increasing gut microbiota and growth performance | [91] |

| 39 | Oligofructose | ? | Asparagus, sugar beet, garlic, onion, chicory, and artichoke | Increasing digestion and gut microbiota | [85, 86, 92] |

| 40 | Arabinoxylooligosaccharides | ? | Wheat bran | Increasing digestion and gut microbiota | [93–95] |

?: unknown.

2.1. Plants and Compounds That Inhibit the Life Cycle of Eimeria

In this section, the phytochemicals and plants, which suppress coccidiosis via intervention with the developmental stages of life cycle in Eimeria species in poultry, are discussed. They are summarized in Table 2. Their chemistry and mechanism of action of phytochemicals and plants are also described below and summarized in Table 2 and Figure 1.

2.1.1. Artemisia annua and Artemisinin

A. annua and its constituent active compound artemisinin have been reported to have anticoccidial action (Table 2). Mechanistic studies show that this compound generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) via degradation of iron-implicated peroxide complex and, therefore, induced oxidative stress. Of note, ROS was documented to directly inhibit sporulation and cell wall formation in Eimeria species, leading to interference with the life cycle of Eimeria [19–23]. In addition, A. annua has lots of phytochemicals, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds which can help birds maintain commensal microflora and take up large amounts of nitrogen. Commensal bacteria play a significant role in enhancing digestion of food and absorption of nutrients and improve innate and acquired immune response in poultry [24].

2.1.2. Condensed Tannins and Pine Bark

The extract from the bark of the pine tree (Pinus radiata), which is rich in condensed tannins, was reported to inhibit the life cycle of Coccidia as evidenced by decreased sporulation of the oocysts of E. tenella, E. maxima, and E. acervulina [25]. The mode of action of condensed tannins was suspected to be penetration of the wall of the oocyst and damage to the cytoplasm since the tannins could inactivate endogenous enzymes responsible for the sporulation process. This was further supported by the appearance of abnormal sporocysts in oocysts [25].

2.1.3. Garlic (Allium sativum) and Allicin

Garlic and its sulfur compounds, allicin, alliin, ajoene, diallyl sulfide, dithiin, and allylcysteine, are reported to have broad antimicrobial activities which can eliminate negative factors of microbial infections. An in vitro study has shown that allicin inhibits sporulation of E. tenella effectively [26–28]. The anticoccidial mechanism of garlic and its sulfur compounds remains elusive.

2.1.4. Selenium, Phenolics, and Green Tea (Camellia sinensis)

Green tea extracts have been shown to significantly inhibit the sporulation process of coccidian oocysts [29, 30]. Accordingly, the selenium and polyphenolic compounds in green tea are thought to be active compounds to inactivate the enzymes responsible for coccidian sporulation [29, 30].

2.1.5. N-3 Fatty Acids, Flavonoids, Vernoside, and Their Plant Sources

Upon the invasion of Eimeria sporozoites into the intestinal epithelium, reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are often produced by host cells, leading to the death of sporulating oocysts [21]. Similarly, another study demonstrated that the extracts from Berberis lyceum, in which berberine was enriched, inhibited the sporozoites of E. tenella in chickens via induction of oxidative stress. Other studies indicated that extracts from Linum usitatissimum [21], Ageratum conyzoides [31], and Vernonia amygdalina [32] controlled coccidian infection via induction of oxidative stress. Moreover, N-3 fatty acids, flavonoids, and vernoside were identified as active compounds present in L. usitatissimum, A. conyzoides, and V. amygdalina, respectively. These compounds were shown to elicit oxidative stress (Table 2). Oxidative stress is known to cause imbalance of oxidant or antioxidant species in the host and is often observed in a wide range of microbial and parasitic infections including coccidiosis [19]. Moreover, these natural extracts not only enhanced chicken growth but also had no noticeable toxicity.

2.1.6. Carica papaya and Papain

Two studies have reported that extracts from C. papaya leaves significantly inhibit coccidiosis [32, 33]. Little is known about the anticoccidial mechanism. Proteolytic destruction of Eimeria by papain and/or inflammatory suppression by vitamin A were proposed as possible mechanisms by which C. papaya and its active compounds acted to suppress coccidiosis [32, 33].

2.1.7. Saponin, Betaine, and Their Plant Sources

Hassan et al. demonstrated that dietary supplementation of guar bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba) suppressed coccidiosis in chickens [34]. This suppression was proposed to be achieved by saponins, presumably the active compounds, which bind with sterol molecules present on the cell membrane of the parasites [34]. Another study also reported that the extracts of M. cordifolia, M. citrifolia, and M. arboreus showed anticoccidial effects in chickens [35]. Saponins were presumed to be the active compounds which could lyse oocysts. In contrast, another report described betaine, an active compound isolated from beet or other plants, as contributing to the stabilization and protection of the epithelial cells in which Eimeria multiply [36].

2.1.8. Essential Oils and Their Plant Sources

Essential oils derived from plants showed inhibition of Eimeria species at different developmental stages (Figure 1). Essential oils are an important natural product resource, which are rich in many phytocompounds. Both in vitro and in vivo studies reported that essential oils can be used as feed additives in chickens to control coccidiosis [1, 11, 12]. Bioactive compounds present in the essential oils extracted from Oreganum compactum, A. absinthium, Rosmarinus officinalis, Anredera cordifolia, Morinda citrifolia, Malvaviscus arboreus, Syzygium aromaticum, Melaleuca alternifolia, Citrus sinensis, and Thymus vulgaris were able to destroy the parasites, including oocysts and sporozoites (Table 1).

2.1.9. Maslinic Acid

Maslinic acid, an active compound in the leaves and fruit of the olive tree (Olea europaea), was originally identified as a novel anticoccidial compound as indicated by the lesion index, the oocyst index, and the anticoccidial index [37]. However, its anticoccidial activity remains unknown.

2.1.10. Proanthocyanidin and Grape Seed

Proanthocyanidin is a naturally occurring polyphenolic antioxidant widely distributed in grape seed and other sources. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract was shown to reduce E. tenella infection as shown by gut pathology, body weight, and mortality [38]. Accordingly, this extract decreased nitric oxide but increased superoxide dismutases in the plasma of chickens [38]. These data suggest that proanthocyanidin from grape seed diminishes coccidiosis via downregulation of oxidative stress.

2.1.11. Dichroa febrifuga

D. febrifuga, also known as Chang Shan, is a Chinese medicinal herb for protozoan diseases. Zhang and coworkers showed that crude extract of D. febrifuga was effective against E. tenella infection in chickens [39]. Febrifugine, an alkaloid, was isolated from this plant and its halogenated derivative, halofuginone, was developed as anticoccidial chemical [10].

2.2. Plants and Compounds That Modulate Host Immunity against Eimeria

From an evolutionary point of view, birds have a complete immune system consisting of innate and adaptive immune responses [96]. Both immune responses are responsible for coccidial clearance and vaccine immunization [12, 97]. Medicinal plants often have immunomodulatory compounds which boost antimicrobial immune responses to uphold homeostasis of poultry health [91, 98]. Therefore, immunoregulatory plant extracts and compounds could be utilized as an alternative method to reinforce immune response against avian coccidiosis. Immunoregulatory phytochemicals for avian coccidiosis are described in Table 3 and Figure 2.

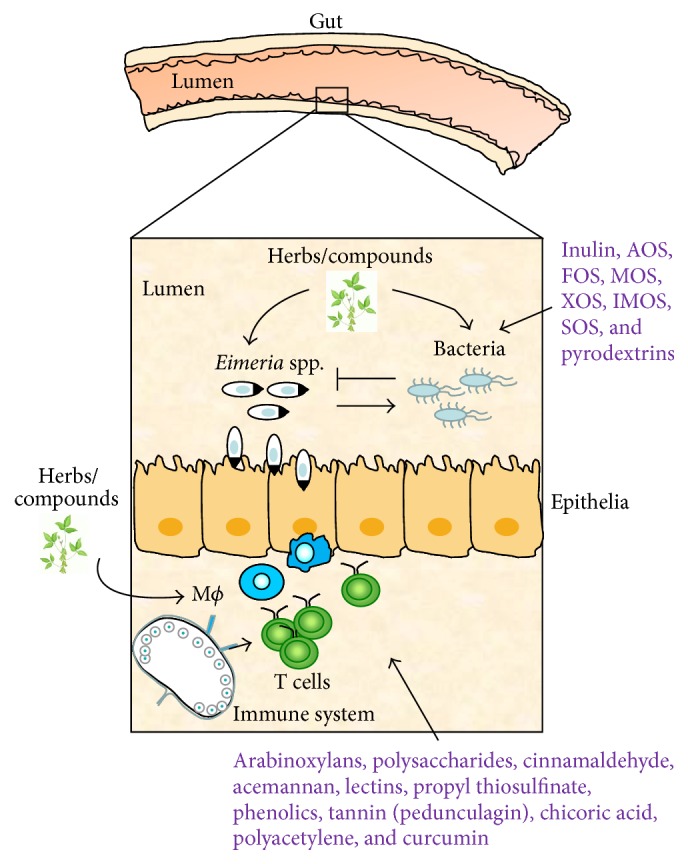

Figure 2.

Immune and prebiotic modulation underlying anticoccidial compounds. In the lumens of bird guts, bacteria and Eimeria species interact with each other. Particularly, some beneficial bacteria can reduce gut lesions caused by Eimeria species. Gut-associated T cells, macrophages, and other immune cells can mount immune responses to harmful Eimeria and bacteria. Phytocompounds from plants can inhibit the multiplication of Eimeria, expand the growth of beneficial bacteria, and/or boost immunity, leading to controlling Eimeria infection in the gut of poultry.

2.2.1. Arabinoxylans, Wheat (Triticum aestivum), and Sugar Cane (Saccharum officinarum)

Akhtar and colleagues showed that arabinoxylan, a bioactive compound from wheat bran, improved coccidiosis in chickens as indicated by body weight, oocyst count, and gut lesions [69]. In contrast, Awais and Akhtar reported that different extracts of sugar cane juice and bagasse protected against coccidiosis in chickens as shown by body weight gain, oocyst shedding, lesion score, and anticoccidial indices [99]. The data from both studies revealed that wheat bran arabinoxylan and sugar cane conferred host protection against Eimeria infection via natural and adaptive immune response. Cell-mediated immunity seemed to be a key factor in response to coccidiosis in chickens when compared to humoral immunity [69, 99].

2.2.2. Polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus Radix, Carthamus tinctorius, Lentinus edodes, and Tremella fuciformis

Guo and colleagues reported that the polysaccharides derived from the herb A. membranaceus Radix and the mushrooms L. edodes and T. fuciformis effectively controlled E. tenella infection in chickens [80]. Concurrent with the anticoccidial protection, the polysaccharides could enhance anticoccidial antibodies and antigen-specific cell proliferation in splenocytes via cellular and humoral immunity to E. tenella in chickens [80]. Their mechanism appeared to stimulate cell proliferation of the lymphocytes via regulation of DNA polymerase activity.

2.2.3. Cinnamaldehyde, Carvacrol, Capsicum Oleoresin, and Turmeric Oleoresin

Two phytonutrient mixtures, VAC (carvacrol, cinnamaldehyde, and Capsicum oleoresin) and MC (Capsicum oleoresin and turmeric oleoresin), were tested for coccidiosis in chickens [70]. The data proved that both combination treatments effectively protected against E. tenella infection. Moreover, both treatments exhibited an increase in NK cells, macrophages, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and their cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-6) and a decrease in TNFSF15 and IL-17F, leading to induction and elevation of host immunity to kill E. tenella in chickens [70].

2.2.4. Aloe and Acemannan

Gadzirayi et al. showed that A. excelsa possesses anticoccidial activity in chickens [36, 43, 100, 101] despite lack of information about its mode of action and its active compound(s). Another study stated that aqueous and ethanolic extracts from A. vera mounted a cell-mediated immune response as well as a humoral response against coccidiosis in chickens. The immunomodulatory compounds could include aloe polysaccharide acemannan (Figure 2), which binds the mannose receptor on macrophages, stimulating them to produce inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 through IL-6 and TNF-α and eventually suppress coccidiosis as shown by greater weight gain and lower fecal oocyst counts [72, 100].

2.2.5. Oriental Plum (Prunus salicina) and Phenolics

One report showed that dietary supplementation of plum fruit powder, rich in phenolic compounds, added to chicken feed significantly diminished E. acervulina infection in chickens as demonstrated by increased body weight gain and reduced fecal oocyst shedding [81]. Accordingly, plum fruit powder greatly augmented the transcription of IFN-γ and IL-15 and splenocyte proliferation, indicating that plum fruit can boost immune response to coccidiosis.

2.2.6. Mushroom (Fomitella fraxinea) and Lectin

One study showed that the lectin derived from a mushroom, F. fraxinea, protected chickens from Eimeria challenge via enhancement of both cellular and humoral immune responses [74]. This work also suggested that this mushroom could enhance both immune responses to Eimeria species in chickens. This study implies that immunoregulatory botanicals such as mushroom can improve poultry growth and development via immune protection from infectious pathogens and toxins. Moreover, botanicals, containing micro- and macronutrients, can increase growth performance in poultry.

2.2.7. Propyl Thiosulfinate and Propyl Thiosulfinate Oxide

One study showed that garlic compounds, propyl thiosulfinate (PTS) and propyl thiosulfinate oxide (PTSO), could alter the expression levels of 1,227 transcripts related to intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) in chickens. PTSO/PTS was shown to activate transcription factor, NF-κB, which plays a key role in regulating the immune response upon infection. Therefore, it seems that a combination of PTSO and PTS rendered chickens more resistant to experimental E. acervulina infection and augmented adaptive immunity, including a higher antibody response and greater splenocyte proliferation, compared with control chickens [75]. Another in vitro study showed that PTS could stimulate splenocyte proliferation and directly kill the sporozoites, pointing to the same conclusion [75].

2.2.8. Tannins and Chicoric Acid from Emblica officinalis and Echinacea purpurea

Tannins and chicoric acid, isolated from E. officinalis [77] and E. purpurea [102], respectively, were reported to effectively elicit humoral immune response against coccidial infection in chickens. However, the mechanism by which both compounds boost anticoccidial immunity is not clear.

2.3. Plants and Compounds That Possess Prebiotic Properties

Like in humans, gut microbiota are important for health and disease in poultry [103]. Gut microbiota perform multiple functions involved in nutrient digestion, gut development and growth, establishment/maintenance of the immune system, suppression of pathogenic microbes, microbial infections, and so forth [8, 104–109]. Thus, promotion of beneficial microbes and reduction of harmful microbes contribute to growth performance and health in poultry [103]. Several studies have indicated that probiotics, containing one or multiple species of Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, and/or Bifidobacterium, can reduce coccidiosis and enhance growth performance in chickens [57, 97, 104, 110, 111]. Currently, little is known about the anticoccidial mechanisms of probiotics. These modes of action have been proposed: maintaining a healthy balance of bacteria by competitive exclusion and antagonism, promoting gut maturation and integrity, modulating immunity and preventing inflammation, altering metabolism by increasing digestive enzyme activity and decreasing bacterial enzyme activity and ammonia production, improving feed intake and digestion, and neutralizing enterotoxins and stimulating the immune system [91, 108]. On the other hand, coccidiosis is frequently accompanied by secondary bacterial infection [71, 105, 106, 112].

Prebiotics refer to nondigestible feed ingredients that promote the growth of probiotics and their activities in guts [113]. As illustrated in Table 4, the most common prebiotics, used in poultry, include inulin, arabinoxylooligosaccharides (AOS), fructooligosaccharides (FOS), mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS), xylooligosaccharides (XOS), isomaltooligosaccharides (IMOS), soy oligosaccharides (SOS), and pyrodextrins [92, 114]. These oligosaccharides are derived from the plants such as chicory, onion, garlic, asparagus, artichoke, leek, bananas, tomatoes, and wheat [92]. Dietary supplementation of these prebiotics to chicken feed has enhanced immune defence against pathogen infection and reduced the mortality rate [91, 115]. The mechanism of prebiotics is yet to be revealed, but they selectively stimulate beneficial bacteria in the intestinal system of the bird. The increasing number of beneficial microbiota excludes the harmful pathogens from colonization in the intestinal track of the bird. Subsequently, healthy hosts can produce a wide variety of bacterions and other immunomodulators that can stimulate macrophages to neutralize the pathogens [114]. Thus, prebiotic-mediated immunological changes may be partially due to direct interaction between prebiotics and gut immune cells as well as due to an indirect action of prebiotics via preferential colonization of probiotics and their products that interact with immune cells [85]. Therefore, prebiotics exert their functions mainly via increasing gut probiotics to suppress pathogens and boosting immune response in chickens to constrain gut pathogens [91]. Moreover, Bozkurt et al. reported that prebiotics diminished coccidial infection in chickens but kept marginal oocyst production that might serve as a source of live vaccine for uninfected chickens [116]. Two other publications emphasized that probiotics composed of Bifidobacterium animalis and Lactobacillus salivarius alleviated the detrimental impact of the Eimeria infection on chickens and improved growth performance [110, 111]. These findings suggest that prebiotics suppress coccidiosis plausibly via indirect regulation of increased probiotics and host immunity. Apparently, prebiotics share many similar anticoccidial mechanisms with probiotics. Overall, dietary supplementation of prebiotics is emerging as a novel approach to control coccidiosis.

2.4. Plants and Compounds with Multiple Mechanisms to Inhibit Coccidiosis

2.4.1. Curcumin and Curcuma longa

As described in Table 2, turmeric (C. longa) has long been used as a spice and medicinal herb. One publication stated that C. longa showed anticoccidial activity [67, 117]. Another reported that curcumin (diferuloylmethane), an active compound in C. longa, consistently destroyed sporozoites of E. tenella [118]. Similarly, a combination of A. annua and C. longa showed anticoccidial efficacy in broilers challenged with a mixture of E. acervulina and E. maxima [119]. In addition, curcumin was shown to enhance coccidiosis resistance as evidenced by increased BW gains and reduced oocyst shedding and gut lesions [21, 67]. Consistently, curcumin elevated host humoral immunity to Eimeria species and diminished gut damage in poultry [21, 67].

2.4.2. Polyacetylenes and Bidens pilosa

As described in Table 2, Yang et al. demonstrated that B. pilosa has exhibited anticoccidial activity in chickens infected with E. tenella as evidenced by survival rate, fecal oocyst count, gut pathology, body weight, and bloody stool [9]. Although the active compounds in B. pilosa responsible for anticoccidial action are unknown, this plant is a rich source of phytochemicals, such as 70 aliphatics, 60 flavonoids, 25 terpenoids, 19 phenylpropanoids, 13 aromatics, 8 porphyrins, and 6 other compounds [120]. Interestingly, one polyacetylene (1-phenyl-1,3-diyn-5-en-7-ol-acetate) and one flavonoid (quercetin-3,3-dimethoxy-7-0-rhamnoglucopyranose) in this plant have been proposed to be active compounds against the protozoan parasite, Plasmodium [121].

However, the identity of the active compounds needs to be further ascertained. The mechanism of B. pilosa and its active compounds is not clear. It is possible that this plant and its active compounds intervene in the initial phases of the Eimeria life cycle because the phases may be liable to chemical attack when compared with the oocyst whose wall is very resistant to physical and chemical insults. In addition, B. pilosa was shown to modulate host immunity [122], which might have impact on coccidiosis.

Compared to anticoccidial drugs, B. pilosa was shown to produce little or no drug resistance in Eimeria [9]. Botanicals developed low resistance in Eimeria probably because different compounds target multiple pathways related to drug resistance [9, 12].

It should be noted that the plant- and phytochemical-based remedies can be used per se or in combination with other anticoccidial agents. This idea was further confirmed by one publication indicating that Echinacea, an immunotherapeutic herbal extract, was used to boost the immunization efficacy in chickens in combination with anticoccidial vaccines [78].

3. Conclusions and Perspectives

Coccidiosis is a deadly and debilitating infectious disease in poultry, which is caused by enteric protozoan parasites, Eimeria species, in the guts of birds. These parasites damage the guts of the birds, leading to moderate clinical symptoms such as sick bird appearance, bloody stool, hemorrhage, and gut lesions and death. Pathogens (Eimeria species, swallowed oocyst counts, etc.), host genetics, and environmental factors could influence the clinical outcome of avian coccidiosis. Current prophylaxis and therapy for coccidiosis comprise anticoccidial chemicals, vaccines, and natural products. Plants are a rich source of phytochemicals against coccidiosis. Here, we summarized the chemistry and biology of over 68 plants and compounds which prevented and treated avian coccidiosis via the regulation of the life cycle of Eimeria species and host immunity and gut microflora in experimental and field trail studies. Emphasis was placed on recent advances in the understanding of the potential of these plants and compounds to prevent and/or treat avian coccidiosis. Moreover, the actions, mechanisms, and therapeutic potential of these plant compounds and/or extracts in avian coccidiosis and new insights into the advantage of plant extracts and compounds that simultaneously regulate Eimeria, bacteria, and immune cells were discussed. Comprehensive information about the structure, activity, and modes of action of these compounds can aid research and development of anticoccidial remedies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their laboratory members and Dr. C. L. T. Chang for their constructive suggestions. They also thank the authors whose publications were cited for their contributions.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contributions

Thangarasu Muthamilselvan and Tien-Fen Kuo equally contributed to this study.

References

- 1.Quiroz-Castañeda R. E., Dantán-González E. Control of avian coccidiosis: future and present natural alternatives. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:11. doi: 10.1155/2015/430610.430610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert E. R., Cox C. M., Williams P. M., et al. Eimeria species and genetic background influence the serum protein profile of broilers with coccidiosis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014636.e14636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joyner L., Long P. The specific characters of the Eimeria, with special reference to the Coccidia of the fowl. Avian Pathology. 2008;3(3):145–157. doi: 10.1080/03079457409353827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman H. D. Milestones in avian coccidiosis research: a review. Poultry Science. 2014;93(3):501–511. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman H. D., Jeffers T. K., Williams R. B. Forty years of monensin for the control of coccidiosis in poultry. Poultry Science. 2010;89(9):1788–1801. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DPI global. Cooci-Guard. 2016, http://www.dpiglobal.com/products/cocci-guard.

- 7.Gokila T., Rajalekshmi M., Haridasan C., Hannah K. WO2014004761. World Intellectual Property Organization; 2014. Plant parts and extracts having anticoccidial activity. [Google Scholar]

- 8.GreenVet. Apacox. 2016, http://www.greenvet.com/index.php/en/products-for-feed-mills/poultry-and-game-birds/722-feed-avicoli-apacox.

- 9.Yang W. C., Tien Y. J., Chung C. Y., et al. Effect of Bidens pilosa on infection and drug resistance of Eimeria in chickens. Research in Veterinary Science. 2015;98:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edgar S. A., Flanagan C. Efficacy of Stenorol (halofuginone). I. Against recent field isolates of six species of chicken coccidia. Poultry Science. 1979;58(6):1469–1475. doi: 10.3382/ps.0581469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas R. Z., Colwell D. D., Gilleard J. Botanicals: an alternative approach for the control of avian coccidiosis. World's Poultry Science Journal. 2012;68(2):203–215. doi: 10.1017/s0043933912000268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bozkurt M., Giannenas I., Küçükyilmaz K., Christaki E., Florou-Paneri P. An update on approaches to controlling coccidia in poultry using botanical extracts. British Poultry Science. 2013;54(6):713–727. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2013.849795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blake D. P., Tomley F. M. Securing poultry production from the ever-present Eimeria challenge. Trends in Parasitology. 2014;30(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammond D. Life cycles and development of coccidia. The Coccidia. 1973:45–79. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Z. Modernization: one step at a time. Nature. 2011;480(7378):S90–S92. doi: 10.1038/480s90a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efferth T., Koch E. Complex interactions between phytochemicals. The multi-target therapeutic concept of phytotherapy. Current Drug Targets. 2011;12(1):122–132. doi: 10.2174/138945011793591626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang C. L. T., Lin Y., Bartolome A. P., Chen Y.-C., Chiu S.-C., Yang W.-C. Herbal therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus: chemistry, biology, and potential application of selected plants and compounds. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:33. doi: 10.1155/2013/378657.378657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willcox M. L., Bodeker G. Traditional herbal medicines for malaria. British Medical Journal. 2004;329(7475):1156–1159. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen P. C. Nitric oxide production during Eimeria tenella infections in chickens. Poultry Science. 1997;76(6):810–813. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.6.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh H., Youn H., Noh J., Jang D., Kang Y. Anticoccidial effects of artemisinin on the Eimeria tenella . Korean Journal of Veterinary Research. 1995;35:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen P. C., Danforth H. D., Augustine P. C. Dietary modulation of avian coccidiosis. International Journal for Parasitology. 1998;28(7):1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Almeida G. F., Horsted K., Thamsborg S. M., Kyvsgaard N. C., Ferreira J. F. S., Hermansen J. E. Use of Artemisia annua as a natural coccidiostat in free-range broilers and its effects on infection dynamics and performance. Veterinary Parasitology. 2012;186(3-4):178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Cacho E., Gallego M., Francesch M., Quílez J., Sánchez-Acedo C. Effect of artemisinin on oocyst wall formation and sporulation during Eimeria tenella infection. Parasitology International. 2010;59(4):506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brisbin J. T., Gong J., Sharif S. Interactions between commensal bacteria and the gut-associated immune system of the chicken. Animal hEalth Research Reviews. 2008;9(1):101–110. doi: 10.1017/s146625230800145x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molan A. L., Liu Z., De S. Effect of pine bark (Pinus radiata) extracts on sporulation of coccidian oocysts. Folia Parasitologica. 2009;56(1):1–5. doi: 10.14411/fp.2009.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alnassan A. A., Thabet A., Daugschies A., Bangoura B. In vitro efficacy of allicin on chicken Eimeria tenella sporozoites. Parasitology Research. 2015;114(10):3913–3915. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4637-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elkhtam A., Shata A., El-Hewaity M. Efficacy of turmeric (Curcuma longa) and garlic (Allium sativum) on Eimeria species in broilers. International Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 2014;3(3):349–356. doi: 10.14419/ijbas.v3i3.3142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pourali M., Kermanshahi H., Golian A., Razmi G. R., Soukhtanloo M. Antioxidant and anticoccidial effects of garlic powder and sulfur amino acids on Eimeria-infected and uninfected broiler chickens. Iranian Journal of Veterinary Research. 2014;15(3):227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang S. I., Jun M.-H., Lillehoj H. S., et al. Anticoccidial effect of green tea-based diets against Eimeria maxima . Veterinary Parasitology. 2007;144(1-2):172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molan A.-L., Faraj A. M. Effect of selenium-rich green tea extract on the course of sporulation of Eimeria oocysts. Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2015;14(4):68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nweze N. E., Obiwulu I. S. Anticoccidial effects of Ageratum conyzoides . Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;122(1):6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AL-Fifi Z. Effect of leaves extract of Carica papaya, Vernonia amigdalina and Azadiratcha indica on the coccidiosis in free-range chickens. Asian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2007;1(1):26–32. doi: 10.3923/ajas.2007.26.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nghonjuyi N. W. Efficacy of ethanolic extract of Carica papaya leaves as a substitute of sulphanomide for the control of coccidiosis in KABIR chickens in Cameroon. Journal of Animal Health and Production. 2015;3(1):21–27. doi: 10.14737/journal.jahp/2015/3.1.21.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hassan S. M., El-Gayar A. K., Cadwell D. J., Bailey C. A., Cartwright A. L. Guar meal ameliorates Eimeria tenella infection in broiler chicks. Veterinary Parasitology. 2008;157(1-2):133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakhmani S. I., Wina E., Pasaribu T. Preliminary study on several indonesian plants as feed additive and their effect on Eimeria tenella oocystes. Proceedings of the 16th AAAP Animal Science Congress; 2014; Yogyakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Augustine P. C., Mcnaughton J. L., Virtanen E., Rosi L. Effect of betaine on the growth performance of chicks inoculated with mixed cultures of avian Eimeria species and on invasion and development of Eimeria tenella and Eimeria acervulina in vitro and in vivo . Poultry Science. 1997;76(6):802–809. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.6.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Pablos L. M., Dos Santos M. F. B., Montero E., Garcia-Granados A., Parra A., Osuna A. Anticoccidial activity of maslinic acid against infection with Eimeria tenella in chickens. Parasitology Research. 2010;107(3):601–604. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1901-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang M. L., Suo X., Gu J. H., Zhang W. W., Fang Q., Wang X. Influence of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract in broiler chickens: effect on chicken coccidiosis and antioxidant status. Poultry Science. 2008;87(11):2273–2280. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang D.-F., Sun B.-B., Yue Y.-Y., Zhou Q.-J., Du A.-F. Anticoccidial activity of traditional Chinese herbal Dichroa febrifuga Lour. extract against Eimeria tenella infection in chickens. Parasitology Research. 2012;111(6):2229–2233. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3071-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price K. R. Use of live vaccines for coccidiosis control in replacement layer pullets. Journal of Applied Poultry Research. 2012;21(3):679–692. doi: 10.3382/japr.2011-00486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Youn H. J., Noh J. W. Screening of the anticoccidial effects of herb extracts against Eimeria tenella . Veterinary Parasitology. 2001;96(4):257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(01)00385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman B., Begum T., Sarker Y. A., et al. Comparative efficacy of alcoholic extracts of black Peppers (Piper nigrum) and Chutra leaves (Urtica dioica) with Esb3 against coccidiosis in chickens. Research in Agriculture Livestock and Fisheries. 2015;2(1):117–124. doi: 10.3329/ralf.v2i1.23043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kheirabadi K. P., Katadj J. K., Bahadoran S., Teixeira da Silva J. A., Samani A. D., Bashi M. C. Comparison of the anticoccidial effect of granulated extract of Artemisia sieberi with monensin in experimental coccidiosis in broiler chickens. Experimental Parasitology. 2014;141(1):129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jamshidi S. M. M., Jamshidi S. M. M., Mehr M. A. R. Comparsion between anti coccidial effectes of Artemisia siberi extract and apacox copmplex and lasalosid in experimental infected broilers with coccidiosis. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal. 2014;7(2):453–460. doi: 10.13005/bpj/511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaboutari J., Arab H. A., Ebrahimi K., Rahbari S. Prophylactic and therapeutic effects of a novel granulated formulation of Artemisia extract on broiler coccidiosis. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2014;46(1):43–48. doi: 10.1007/s11250-013-0444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adamu M., Boonkaewwan C. Effect of Lepidium sativum L.(garden cress) seed and its extract on experimental Eimeria tenella infection in broiler chickens. Kasetsart Journal. 2014;48:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drǎgan L., Györke A., Ferreira J. F. S., et al. Effects of Artemisia annua and Foeniculum vulgare on chickens highly infected with Eimeria tenella (phylum Apicomplexa) Acta veterinaria Scandinavica. 2014;56:p. 22. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-56-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ola-Fadunsin S. D., Ademola I. O. Anticoccidial effects of Morinda lucida acetone extracts on broiler chickens naturally infected with Eimeria species. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2014;52(3):330–334. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.836545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bakari G. G., Max R. A., Mdegela R. H., Phiri E. C. J., Mtambo M. M. A. Effect of resinous extract from Commiphora swynnertonii (Burrt) on experimental coccidial infection in chickens. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2013;45(1):455–459. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ola-Fadunsin S. D., Ademola I. O. Direct effects of Moringa oleifera Lam (Moringaceae) acetone leaf extract on broiler chickens naturally infected with Eimeria species. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2013;45(6):1423–1428. doi: 10.1007/s11250-013-0380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bozkurt M., Selek N., Küçükyilmaz K., et al. Effects of dietary supplementation with a herbal extract on the performance of broilers infected with a mixture of Eimeria species. British Poultry Science. 2012;53(3):325–332. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2012.699673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anosa G. N., Okoro O. J. Anticoccidial activity of the methanolic extract of Musa paradisiaca root in chickens. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2011;43(1):245–248. doi: 10.1007/s11250-010-9684-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meskerem A., Boonkaewwan C. Protective effects of Moringa stenopetala leaf supplemented diets on Eimeria tenella infected broiler chickens in debre zeit, central, Ethiopia. Kasetsart Journal. 2013;47(3):398–406. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chandrakesan P., Muralidharan K., Kumar V. D., Ponnudurai G., Harikrishnan T. J., Rani K. Efficacy of a herbal complex against cecal coccidiosis in broiler chickens. Veterinary Archives. 2009;79(2):199–203. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Owai P. U., Gloria M. Effects of components of Melia azadirachta on coccidia infections in broilers in Calabar, Nigeria. International Journal of Poultry Science. 2010;9(10):931–934. doi: 10.3923/ijps.2010.931.934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naidoo V., McGaw L. J., Bisschop S. P. R., Duncan N., Eloff J. N. The value of plant extracts with antioxidant activity in attenuating coccidiosis in broiler chickens. Veterinary Parasitology. 2008;153(3-4):214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee J. J., Kim D. H., Lim J. J., et al. Anticoccidial effect of supplemental dietary Galla rhois against infection with Eimeria tenella in chickens. Avian Pathology. 2012;41(4):403–407. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2012.702888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allen P. C., Lydon J., Danforth H. D. Effects of components of Artemisia annua on coccidia infections in chickens. Poultry Science. 1997;76(8):1156–1163. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.8.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malik T. A., Kamili A. N., Chishti M. Z., Tanveer S., Ahad S., Johri R. K. In vivo anticoccidial activity of berberine [18, 5,6-dihydro-9,10-dimethoxybenzo(g)-1,3-benzodioxolo(5,6-a) quinolizinium]—an isoquinoline alkaloid present in the root bark of Berberis lycium . Phytomedicine. 2014;21(5):663–669. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alagawany M., El-Hack M., Farag M., Tiwari R., Dhama K. Biological effects and modes of action of carvacrol in animal and poultry pro-duction and health-a review. Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences. 2015;3(2s):73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Remmal A., Achahbar S., Bouddine L., Chami N., Chami F. In vitro destruction of Eimeria oocysts by essential oils. Veterinary Parasitology. 2011;182(2–4):121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kostadinović L. M., Čabarkapa I. S., Levic J. D., Kormanjoš Š. M., Teodosin S., Sredanović S. Effect of Artemisia absinthium essential oil on antioxidative systems of broiler's liver. Food and Feed Research. 2014;41(1):11–17. doi: 10.5937/ffr1401011k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frankič T., Voljč M., Salobir J., Rezar V. Use of herbs and spices and their extracts in animal nutrition. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica. 2009;94(2):95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arczewska-Włosek A., Świątkiewicz S. Improved performance due to dietary supplementation with selected herbal extracts of broiler chickens infected with Eimeria spp. Journal of Animal and Feed Sciences. 2013;22(3):257–263. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cox S. D., Mann C. M., Markham J. L., et al. The mode of antimicrobial action of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea tree oil) Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2000;88(1):170–175. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reisinger N., Steiner T., Nitsch S., Schatzmayr G., Applegate T. J. Effects of a blend of essential oils on broiler performance and intestinal morphology during coccidial vaccine exposure. Journal of Applied Poultry Research. 2011;20(3):272–283. doi: 10.3382/japr.2010-00226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim D. K., Lillehoj H. S., Lee S. H., Jang S. I., Lillehoj E. P., Bravo D. Dietary Curcuma longa enhances resistance against Eimeria maxima and Eimeria tenella infections in chickens. Poultry Science. 2013;92(10):2635–2643. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang D.-F., Sun B.-B., Yue Y.-Y., et al. Anticoccidial effect of halofuginone hydrobromide against Eimeria tenella with associated histology. Parasitology Research. 2012;111(2):695–701. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2889-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Akhtar M., Tariq A. F., Awais M. M., et al. Studies on wheat bran Arabinoxylan for its immunostimulatory and protective effects against avian coccidiosis. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2012;90(1):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee S. H., Lillehoj H. S., Jang S. I., Lee K. W., Bravo D., Lillehoj E. P. Effects of dietary supplementation with phytonutrients on vaccine-stimulated immunity against infection with Eimeria tenella . Veterinary Parasitology. 2011;181(2-4):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orengo J., Buendía A. J., Ruiz-Ibáñez M. R., et al. Evaluating the efficacy of cinnamaldehyde and Echinacea purpurea plant extract in broilers against Eimeria acervulina . Veterinary Parasitology. 2012;185(2):158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Babak D., Nahashon S. N. A review on effects of Aloe vera as a feed additive in broiler chicken diets. Annals of Animal Science. 2014;14(3):491–500. doi: 10.2478/aoas-2014-0026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yim D., Kang S. S., Kim D. W., Kim S. H., Lillehoj H. S., Min W. Protective effects of Aloe vera-based diets in Eimeria maxima-infected broiler chickens. Experimental Parasitology. 2011;127(1):322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dalloul R. A., Lillehoj H. S., Lee J.-S., Lee S.-H., Chung K.-S. Immunopotentiating effect of a Fomitella fraxinea-derived lectin on chicken immunity and resistance to coccidiosis. Poultry Science. 2006;85(3):446–451. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.3.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim D. K., Lillehoj H. S., Lee S. H., Lillehoj E. P., Bravo D. Improved resistance to Eimeria acervulina infection in chickens due to dietary supplementation with garlic metabolites. British Journal of Nutrition. 2013;109(1):76–88. doi: 10.1017/s0007114512000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rose P., Whiteman M., Moore P. K., Yi Z. Z. Bioactive S-alk(en)yl cysteine sulfoxide metabolites in the genus Allium: the chemistry of potential therapeutic agents. Natural Product Reports. 2005;22(3):351–368. doi: 10.1039/b417639c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaleem Q. M., Akhtar M., Awais M. M., et al. Studies on Emblica officinalis derived tannins for their immunostimulatory and protective activities against coccidiosis in industrial broiler chickens. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014:10. doi: 10.1155/2014/378473.378473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Allen P. C. Dietary supplementation with Echinacea and development of immunity to challenge infection with coccidia. Parasitology Research. 2003;91(1):74–78. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0938-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bauer R. Immunomodulatory Agents from Plants. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1999. Chemistry, analysis and immunological investigations of Echinacea phytopharmaceuticals; pp. 41–88. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guo F. C., Kwakkel R. P., Williams B. A., et al. Effects of mushroom and herb polysaccharides on cellular and humoral immune responses of Eimeria tenella-infected chickens. Poultry Science. 2004;83(7):1124–1132. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.7.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee S.-H., Lillehoj H. S., Lillehoj E. P., et al. Immunomodulatory properties of dietary plum on coccidiosis. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2008;31(5):389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jaiswal R., Karaköse H., Rühmann S., et al. Identification of phenolic compounds in plum fruits (Prunus salicina l. and Prunus domestica l.) by high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and characterization of varieties by quantitative phenolic fingerprints. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2013;61(49):12020–12031. doi: 10.1021/jf402288j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nabizadeh A. The effect of inulin on broiler chicken intestinal microflora, gut morphology, and performance. Journal of Animal and Feed Sciences. 2012;21(4):725–734. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sevane N., Bialade F., Velasco S., et al. Dietary inulin supplementation modifies significantly the liver transcriptomic profile of broiler chickens. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6, article e98942) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Janardhana V., Broadway M. M., Bruce M. P., et al. Prebiotics modulate immune responses in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue of chickens. The Journal of Nutrition. 2009;139(7):1404–1409. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.105007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim G.-B., Seo Y. M., Kim C. H., Paik I. K. Effect of dietary prebiotic supplementation on the performance, intestinal microflora, and immune response of broilers. Poultry Science. 2011;90(1):75–82. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Maesschalck C., Eeckhaut V., Maertens L., et al. Effects of xylo-oligosaccharides on broiler chicken performance and microbiota. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2015;81(17):5880–5888. doi: 10.1128/aem.01616-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang W. F., Li D. F., Lu W. Q., Yi G. F. Effects of isomalto-oligosaccharides on broiler performance and intestinal microflora. Poultry Science. 2003;82(4):657–663. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mookiah S., Sieo C. C., Ramasamy K., Abdullah N., Ho Y. W. Effects of dietary prebiotics, probiotic and synbiotics on performance, caecal bacterial populations and caecal fermentation concentrations of broiler chickens. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2014;94(2):341–348. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pourabedin M., Zhao X. Prebiotics and gut microbiota in chickens. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2015;362(15) doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv122.fnv122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sugiharto S. Role of nutraceuticals in gut health and growth performance of poultry. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jssas.2014.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Al-Sheraji S. H., Ismail A., Manap M. Y., Mustafa S., Yusof R. M., Hassan F. A. Prebiotics as functional foods: a review. Journal of Functional Foods. 2013;5(4):1542–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rodríguez M. L., Rebolé A., Velasco S., Ortiz L. T., Treviño J., Alzueta C. Wheat- and barley-based diets with or without additives influence broiler chicken performance, nutrient digestibility and intestinal microflora. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2012;92(1):184–190. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tako E., Glahn R. P., Knez M., Stangoulis J. C. The effect of wheat prebiotics on the gut bacterial population and iron status of iron deficient broiler chickens. Nutrition Journal. 2014;13(1, article 58) doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eeckhaut V., Van Immerseel F., Dewulf J., et al. Arabinoxylooligosaccharides from wheat bran inhibit Salmonella colonization in broiler chickens. Poultry Science. 2008;87(11):2329–2334. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yegani M., Korver D. R. Factors affecting intestinal health in poultry. Poultry Science. 2008;87(10):2052–2063. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Abbas R. Z., Iqbal Z., Khan A., et al. Options for integrated strategies for the control of avian coccidiosis. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology. 2012;14(6):1014–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Akram M., Hamid A., Khalil A., et al. Review on medicinal uses, pharmacological, phytochemistry and immunomodulatory activity of plants. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2014;27(3):313–319. doi: 10.1177/039463201402700301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Awais M. M., Akhtar M. Evaluation of some sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) Extracts for immunostimulatory and growth promoting effects in industrial broiler chickens. Pakistan Veterinary Journal. 2012;32(3):398–402. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Akhtar M., Hai A., Awais M. M., et al. Immunostimulatory and protective effects of Aloe vera against coccidiosis in industrial broiler chickens. Veterinary Parasitology. 2012;186(3-4):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gadzirayi C., Mupangwa J., Mutandwa E. Effectiveness of Aloe excelsa in controlling coccidiosis in broilers. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa. 2005;7:74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhai Z., Liu Y., Wu L., et al. Enhancement of innate and adaptive immune functions by multiple Echinacea species. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2007;10(3):423–434. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Adil S., Magray S. N. Impact and manipulation of gut microflora in poultry: a review. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances. 2012;11(6):873–877. doi: 10.3923/javaa.2012.873.877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ohimain E. I., Ofongo R. T. The effect of probiotic and prebiotic feed supplementation on chicken health and gut microflora: a review. International Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances. 2012;4:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Castanon J. I. R. History of the use of antibiotic as growth promoters in European poultry feeds. Poultry Science. 2007;86(11):2466–2471. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Serratosa J., Blass A., Rigau B., et al. Residues from veterinary medicinal products, growth promoters and performance enhancers in food-producing animals: a European Union perspective. Scientific and Technical Review of the Office International des Epizooties (Paris) 2006;25(2):637–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nurmi E., Rantala M. New aspects of Salmonella infection in broiler production. Nature. 1973;241(5386):210–211. doi: 10.1038/241210a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.van der Wielen P. W. J. J., Keuzenkamp D. A., Lipman L. J. A., van Knapen F., Biesterveld S. Spatial and temporal variation of the intestinal bacterial community in commercially raised broiler chickens during growth. Microbial Ecology. 2002;44(3):286–293. doi: 10.1007/s00248-002-2015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vispo C., Karasov W. H. Gastrointestinal Microbiology: Volume 1 Gastrointestinal Ecosystems and Fermentations. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1997. The interaction of avian gut microbes and their host: an elusive symbiosis; pp. 116–155. (Chapman & Hall Microbiology). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Giannenas I., Tsalie E., Triantafillou E., et al. Assessment of probiotics supplementation via feed or water on the growth performance, intestinal morphology and microflora of chickens after experimental infection with Eimeria acervulina, Eimeria maxima and Eimeria tenella . Avian Pathology. 2014;43(3):209–216. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2014.899430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ritzi M. M., Abdelrahman W., Mohnl M., Dalloul R. A. Effects of probiotics and application methods on performance and response of broiler chickens to an Eimeria challenge. Poultry Science. 2014;93(11):2772–2778. doi: 10.3382/ps.2014-04207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Williams R. B. Anticoccidial vaccines for broiler chickens: pathways to success. Avian Pathology. 2002;31(4):317–353. doi: 10.1080/03079450220148988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bindels L. B., Delzenne N. M., Cani P. D., Walter J. Towards a more comprehensive concept for prebiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2015;12(5):303–310. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Alloui M. N., Szczurek W., Świątkiewicz S. The usefulness of prebiotics and probiotics in modern poultry nutrition: a review. Annals of Animal Science. 2013;13(1):17–32. doi: 10.2478/v10220-012-0055-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ganguly S. Supplementation of prebiotics, probiotics and acids on immunity in poultry feed: a brief review. World's Poultry Science Journal. 2013;69(3):639–648. doi: 10.1017/s0043933913000640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bozkurt M., Aysul N., Küçükyilmaz K., et al. Efficacy of in-feed preparations of an anticoccidial, multienzyme, prebiotic, probiotic, and herbal essential oil mixture in healthy and Eimeria spp.-infected broilers. Poultry Science. 2014;93(2):389–399. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Abbas R. Z., Iqbal Z., Khan M. N., Zafar M. A., Zia M. A. Anticoccidial activity of Curcuma longa L. in broilers. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 2010;53(1):63–67. doi: 10.1590/s1516-89132010000100008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Khalafalla R. E., Müller U., Shahiduzzaman M., et al. Effects of curcumin (diferuloylmethane) on Eimeria tenella sporozoites in vitro. Parasitology Research. 2011;108(4):879–886. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2129-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Almeida G. F. D., Thamsborg S. M., Madeira A. M. B. N., et al. The effects of combining Artemisia annua and Curcuma longa ethanolic extracts in broilers challenged with infective oocysts of Eimeria acervulina and E. maxima . Parasitology. 2014;141(3):347–355. doi: 10.1017/s0031182013001443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bartolome A. P., Villaseñor I. M., Yang W.-C. Bidens pilosa L. (Asteraceae): botanical properties, traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:51. doi: 10.1155/2013/340215.340215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Daugschies A., Gässlein U., Rommel M. Comparative efficacy of anticoccidials under the conditions of commercial broiler production and in battery trials. Veterinary Parasitology. 1998;76(3):163–171. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(97)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chang C. L. T., Kuo H. K., Chiang Y. M., et al. Butanol fraction of Bidens pilosa Linn. can prevent Th1-mediated autoimmune diadetes but aggravate Th2-mediated ova-induced asthma. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2005;12(1):79–89. doi: 10.1007/s11373-004-8172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]